by Gideon Marcus

Shifting Vistas

The universe is changing.

One of the fundamental tenets of quantum physics is that one cannot observe the universe without fundamentally affecting it. In ancient times, the stars and planets were objects of mystery. They lay fixed in crystal spheres; they influenced human affairs with strange forces; they were Gods; they were little fires.

And then we observed them with telescope, and the fuzzy waveforms collapsed into particles. The stars were just the Sun's brethren. Planets were actually spheres of matter, and the Earth was one of them. These discoveries did not make the celestial bodies any less interesting, but it did more narrowly confine the bounds of their possible natures.

Still, that left lots of wiggle room for imagination. Why, Venus must be a primeval swamp or perhaps a vast desert. Mars was clearly the home of an elderly civilization, huddling close to their dying canals. Even the Moon might be home to a hardy lichen on its surface (and perhaps a society of aliens beneath it — perhaps they nourished themselves on green cheese).

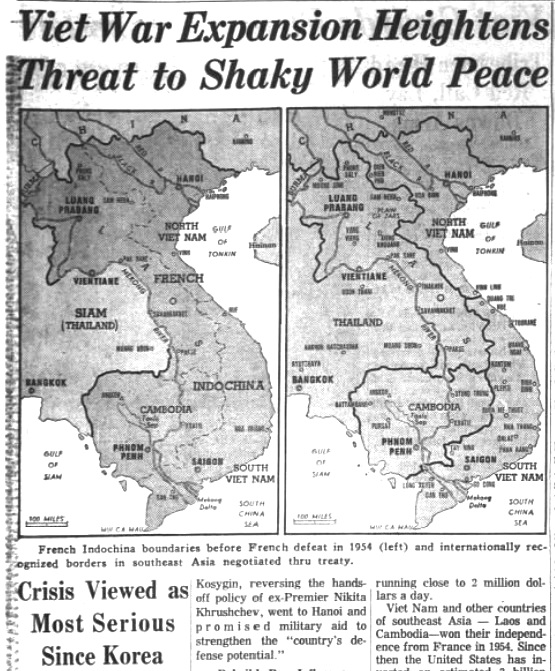

Then came the Pioneers, Rangers, and Mariners. The Pioneers told us that the Moon had no atmosphere at all, and the Rangers confirmed that Luna was a dead, cratered world. Then Mariner 2 dashed our carefully wrought picture of Venus, revealing a searing inferno of a planet.

Now Mariner 4, which zoomed just 6000 feet over the surface of Mars on July 14, has slain another fantasy land. Preliminary data show that the Red Planet has a much thinner atmosphere than expected and no magnetic field. Without significant erosion from wind and rain, and without a liquid core to drive vulcanism and resurfacing, Mars is probably a cratered wasteland like the Moon. We'll know more when photos start coming in (look for an article on the 20th from Kaye Dee).

Again, this does not make Venus or Mars any less interesting…to science. But for science fiction, the stories are yet again constrained. They still exist: Niven's recent Becalmed in Hell takes place in the new Venus; perhaps he'll be the first to set a story on the new Mars. But for the most part, increased knowledge has excluded our solar system from fantastic speculation.

It's no surprise, then, that the very newest science fiction, that coming out in our monthly magazines, has turned to other settings: other dimensions and faraway stars. Or focused closer to home, offering up cautionary and satirical stories of human, terrestrial society.

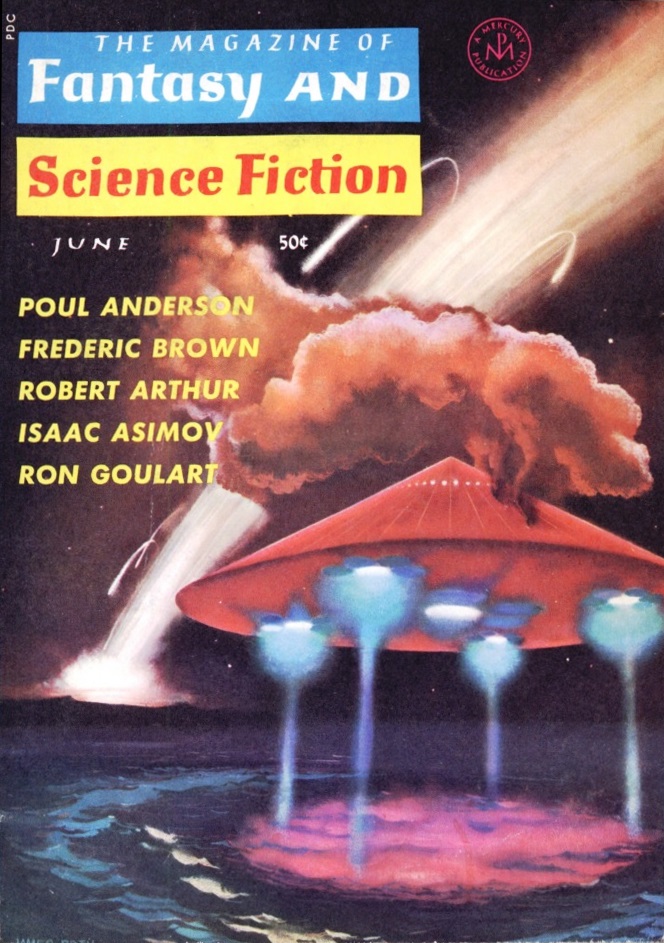

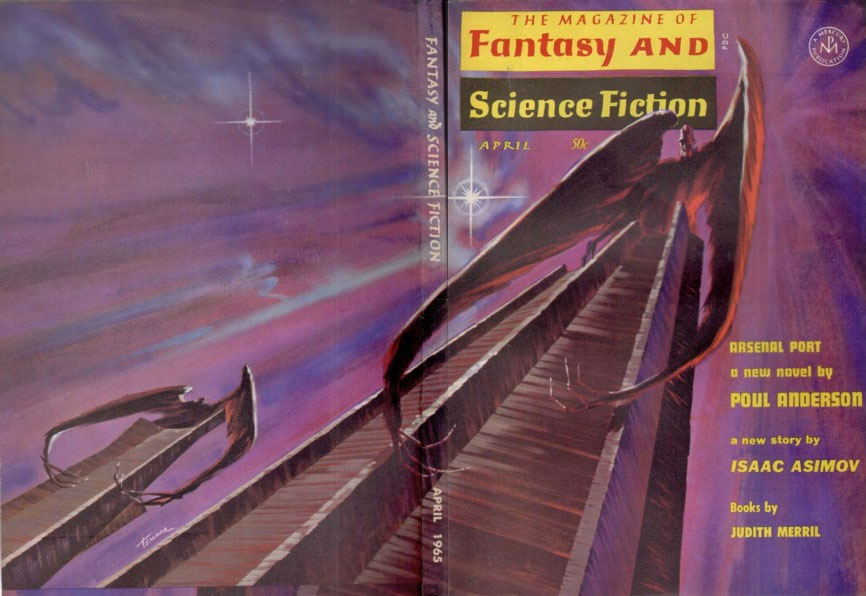

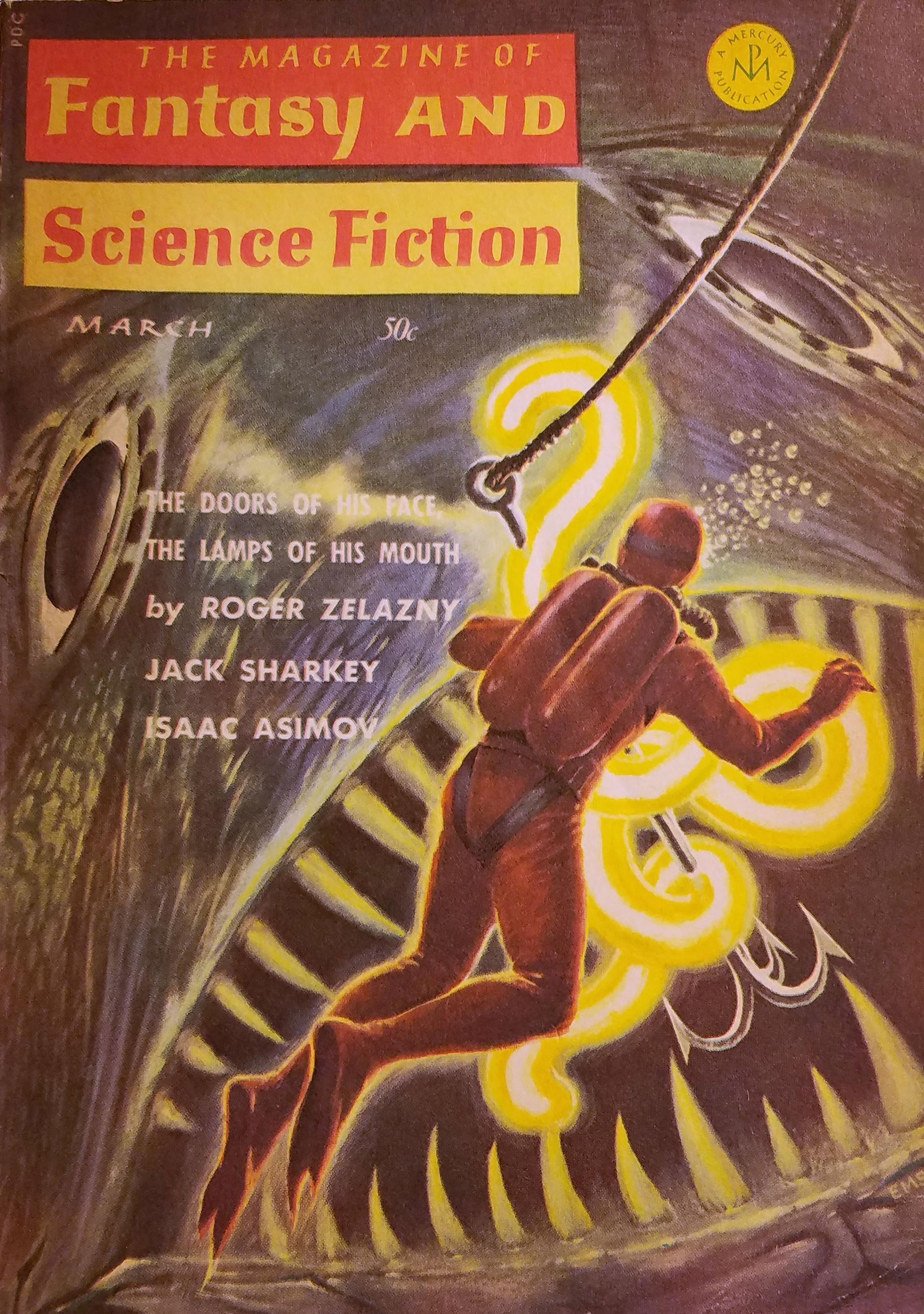

Though it cautiously stays on the safe side of the weird, more nuanced New Wave that has started to flood the pages of our books and digests, this month's Fantasy and Science Fiction offers a nice survey of the current frontier of science fiction:

The issue at hand

by Bert Tanner

The Masculinist Revolt, by William Tenn

At the dawn of the 21st Century, the feminist revolt is complete and there is, with one exception, complete equality between the sexes. This doesn't sit well with one P. Edward Pollyglow, a clothier who finds that demand for his made-for-men jumpsuits has dropped to nil. So he tries to restore le difference between the sexes by reviving that most manly of garments, the codpiece. In so doing, he sets off a revolution that restores men's clubs, dueling, and other brands of overt masculinity.

There are two major flaws in this story. The first is that the piece has no real through line. Things happen, get more ridiculous, and the masculinist revolt eventually overripens and collapses.

The second flaw is the doozy, however. From the second page:

Women kept gaining prestige and political power. The F.E.P.C. started policing discriminatory employment practices in any way based on sex. A Supreme Court decision (Mrs. Staub's Employment Agency for Lady Athletes vs. The New York State Boxing Commission) enunciated the law in Justice Emmeline Craggly's historic words: "Sex is a private, internal matter and ends at the individual's skin. From the skin outwards, in family chores, job opportunities, or even cloting, the sexes must be considered legally interchangeable in all respects save one. That one is the traditional duty of the male to support his family to the limit of his physical powers–the fixed cornerstone of all civilized existence.

I'm sure everyone was fine until the part at the end (bolding added by me). It straw(wo)mans the feminist movement. What women want to day is equality, the freedom to pursue a life as unfettered in opportunity, as rewarding in ambition and compensation as that enjoyed by men. I don't know any women espousing for equality in all fields and a free ride on the back of men.

Thus, what could have been a piquant tale is a flop at the beginning and end, destroying the value of any droll cleverness inbetween.

One star.

I'm not sure how this month's Gahan Wilson piece does any more than fill a page.

Explosion, by Robert Rohrer

The starship Southern Cross, crewed by a mixed complement of Terrans and feline Maxyd, encounters an ancient missile that threatens to destroy the ship if its shields are not raised in time. Unfortunately for two Maxyd, repairs had been underway when the Captain made his fateful decision, and they are killed. The missile turns out to be a dud.

However, the ancient hatred between the two races of the crew, only thinly papered over since a brutal war in recent memory, flares brightly. A mutiny ensues, completing what the ancient alien warhead could not.

In defter hands, I suppose this could have been something. As is, Explosion is both heavy handed and forgettable. Two stars.

Crystal Surfaces, by Theodore L. Thomas

In the future, Thomas posits, data will be stored not with chemical residue (pen/pencil) or magnetic charging (computer tape) but the careful positioning of atoms. Thus, information will be stored and conveyed at the maximum possible density.

Neat idea. Three stars.

Everyone's Hometown Is Guernica, by Willard Marsh

A starving painter adopts a scraggly kitten and, almost simultaneously, is consumed with an art idea he must commit to canvas. As he pours his soul into his work, the kitten disappears, replaced by an alluring, independent woman who cooks and cleans for him, never saying a word. I won't betray the ending, which is powerful, sad and poetic.

This is definitely the standout piece of the issue. Four stars.

The 2-D Problem, by Jody Scott

Things slip into mediocrity again with the subsequent nonsensical piece from Jody Scott. Apparently, folks from Callisto have the ability to translate fiction into reality. This becomes problematic when one Callistan, slated to be an ambassador of sorts to Earth, gets a hold of a comic book and brings Little Orphan Annie to life. Flat life, but life nevertheless.

It's never explained how this power works, and the humor is about as flat as the story's subject matter.

Two stars.

First Context, by Laurence M. Janifer and S. J. Treibich

Speaking of Mariner, it is the subject for this punchline-focused vignette in which the human race gets fined by aliens for letting a probe go errant into a restricted zone.

First Context is like one of those four panel comics that should have ended on panel three.

Two stars.

Behind the Teacher's Back, by Isaac Asimov

A sequel of sorts to Asimov's article in the April issue on the uncertainty principle, Dr. A. describes the discovery of the third of the four presently known fundamental forces of the universe. There's nothing in here I didn't already know, thanks to my time as an astrophysics major, but the energy version of the uncertainty principle is one of my favorite subjects.

You tell me if he succeeded in conveying what he was trying to convey.

Four stars.

A Stick for Harry Eddington, by Chad Oliver

By the turn of the 21st Century, retirement comes at 50 and boredom soon after. What's left to do when one's salad days are in the rear view mirror, the kids are off to college, and the spouse fails to excite? Have your mind exchanged with someone from a "primitive" culture, one which still values the important things in life!

Stick seems more a vehicle to denigrate the upcoming decadent, materialistic life we seem to be headed for. On the other hand, the sting in the story's ending is pretty clever.

A solid three stars.

The Immortal, by Gordon R. Dickson

Hundreds of parsecs behind enemy lines, the ancient fighting ship La Chasse Gallerie, struggles its way home over a series of ten light-year hops. Its pilot and sole crewmember, who left Earth a young man, is now a staggering two hundred years old. Yet he continues to fend off enemy interceptors, always gustily singing one French shanty or another.

Back on Earth, it is concluded that this survivor, who has somehow pushed the boundaries of the human life span, might hold the key to immortality. A risky penetration and rescue mission is executed.

The first ten pages of this story are rather dry and slow, and I can't help but think they could have been condensed into a page or two. Also marring this piece is the melodramatic portrayal of the leader of the rescuing task force, a bitter battle-fatigued man with a death wish, and the geriatric specialist assigned to his ship.

But The Immortal eventually hits its stride, and if the end result is not perfection, it is not unsatisfying.

Call it a high three stars.

The New Frontier

Science fiction, like science, seems to be in a transitional stage. As writers explore the new, as-yet unsurveyed realms of the universe, the resulting stories should only grow in quality and scope. Until, of course, some new probe upends everything again!

What frontier's literary exploration do you look most forward to?

![[July 16, 1965] To Fresh Woods (August 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650716cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 18, 1965] Rubber Ball (or Skip the End) (June 1965 <i>Fantasy & Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650518cover-664x372.jpg)

![[April 22, 1965] Cracker Jack issue (May 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650422cover-575x372.jpg)

![[Mar. 18, 1965] Per Aspera (April 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/650318cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 16, 1965] Return to a Quagmire (March 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/650214cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 18, 1965] Doors also open (February 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650118cover-672x372.jpg)

![[December 15, 1964] Failed Flight of Fancy (January 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/641215cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 19, 1964] Ding Dong (December 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641119cover-425x372.jpg)

![[October 20, 1964] The Struggle (November 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641020cover-660x372.jpg)

![[September 22, 1964] Fall back! (October 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640922cover-672x372.jpg)