by Tam Phan (Secret Asian Man)

There’s a volcano that’s ready to erupt on the silver screens, so prepare yourselves for a blast of truth, fury, and funk that has no patience for politeness. These three films, Watermelon Man, The Landlord, and Cotton Comes to Harlem, take a swing at the beast that is American racism as they stumble in their own strange ways trying to wrap their arms around it. These films attempt to not let their audiences off easy as they slap them across the face, daring white America to feel what it’s like to be on the wrong end of the stick. Whether you’re a white boy having your spiritual awakening in a Black neighborhood or a white man literally waking up Black, these films don’t just entertain. They challenge and provoke you with some honesty and a loud Black voice that is no longer asking to be heard.

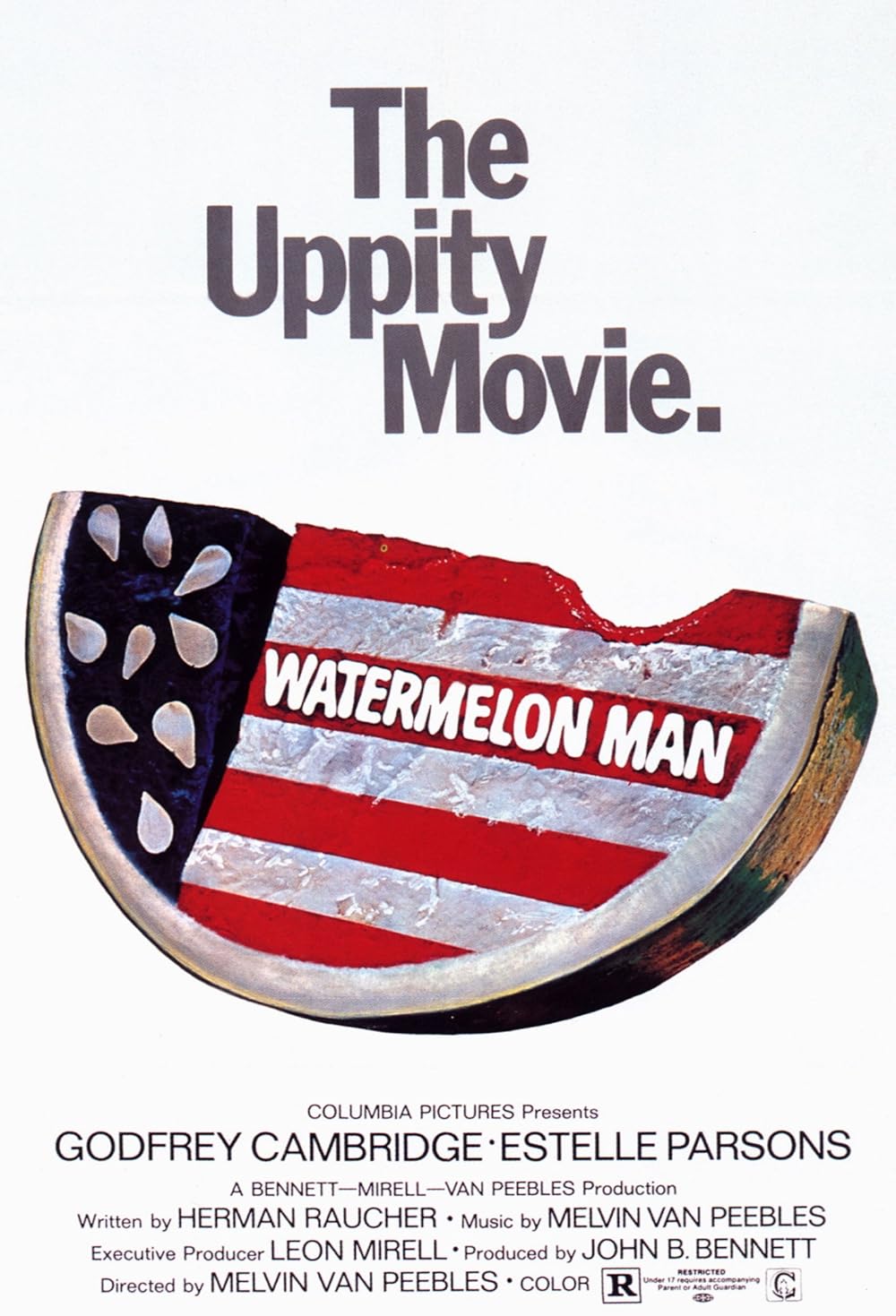

Watermelon Man: A Punch That Lands… Mostly

Sometimes a movie comes along that doesn’t ask for permission. It just barges in the front door and stares you in the face until you have no choice but to confront it. Watermelon Man is that kind of movie. Melvin Van Peebles throws a grenade into the laps of polite white America, and even when it is a bit of a dud, there is no denying that someone threw it. I was not sure if I was supposed to laugh, cry, or throw my slippers at the screen. Maybe all three. This movie does have guts, but it could have been better executed.

Jeff Gerber (played by Godfrey Cambridge, wearing whiteface so thick he looks like a walking toothpaste ad), a smug, self-satisfied, loud racist that thinks himself a “good guy”, wakes up one morning to find himself Black with no warning or explanation. The world predictably turns on him and suddenly all that privilege he wore like a second skin gets ripped clean off. He is left with the nightmare he has spent his entire life thinking only happens to other people. Insert a crash course in American racism here, delivered with the subtlety of a sledgehammer, but for some reason it works. It almost feels natural. The other shoe has dropped, and Van Peebles delivers without wasting any time easing you into anything.

White before the fall.

Jeff’s life falls apart in a matter of days. He has a meltdown, his wife recoils from him, he is stopped on the streets by would-be citizens and the police, and his neighbors plot against him. It is brutal to watch. If I was supposed to laugh, it was not clear what I should be laughing at. His attempts to “whiten” himself using creams and spiritual solutions reminds me that for those of us not born with the golden ticket of whiteness – men like me, a Vietnamese immigrant who has seen the slant of every dirty look and been cowed by the title of being the “model minority” – this movie hits a nerve that is still raw. It is ultimately unsatisfying to see this happen to a white man because this is happening to a Black man and by proxy, all men who are not white.

White away your fears.

Watermelon Man is not perfect. It walks a strange line between cartoon and cautionary tale. Half of the time, it is all slapstick and Three Stooges, but when the ugliness shows up – the broken marriage and neighbors chasing him out – the movie whiffs on the gut punch. The movie wants to have it both ways and it is only funny if you’re meant to laugh at the clown without feeling sorry for him at the same time. Jeff’s resignation to his circumstances at the end is purely survival. He is not noble. He is not redeemed. He simply has no choice. There is nothing funny about that.

Peebles is angry, without a doubt. I can respect that. We need more Black men behind the camera screaming at America’s cruelties. I can understand the need to soften the blow with a bit of comedy, but this movie pulls its punches. Why are we quickly made to feel sympathy for a man who, just days before, would have gone out of his way to avoid shaking my hand? I suppose that I feel sorry for him because I understand him, but I wonder how it lands for those that do not. That is what concerns me. Maybe Watermelon Man intends to shock white folks awake without scaring them too much, but in doing so, it sells short the very fury it is supposed to be about.

I walked out of Watermelon Man with a mix of satisfaction and frustration. Satisfaction because it speaks a truth that a lot of folks would rather ignore. Frustration because part of me wanted it to cut deeper. Despite that, I appreciate this film. Van Peebles delivers a movie that nobody else in Hollywood would dare to make. In a time when the safe move is to stay quiet, Watermelon Man attempts to hit you with the truth. I just wish it was a truth that cut like a knife rather than a rubber chicken.

What if we didn't pull our punches?

This movie needed to be made, and I am glad that it exists. It starts the conversation about an underlying condition in America that has been left undiagnosed for far too long. If this is where it begins, I can not fault it for being cautious. Despite being critical of this movie I think it is worth seeing if for no other reason than to see how easily skin color becomes a prison here in America.

3 out of 5 stars.

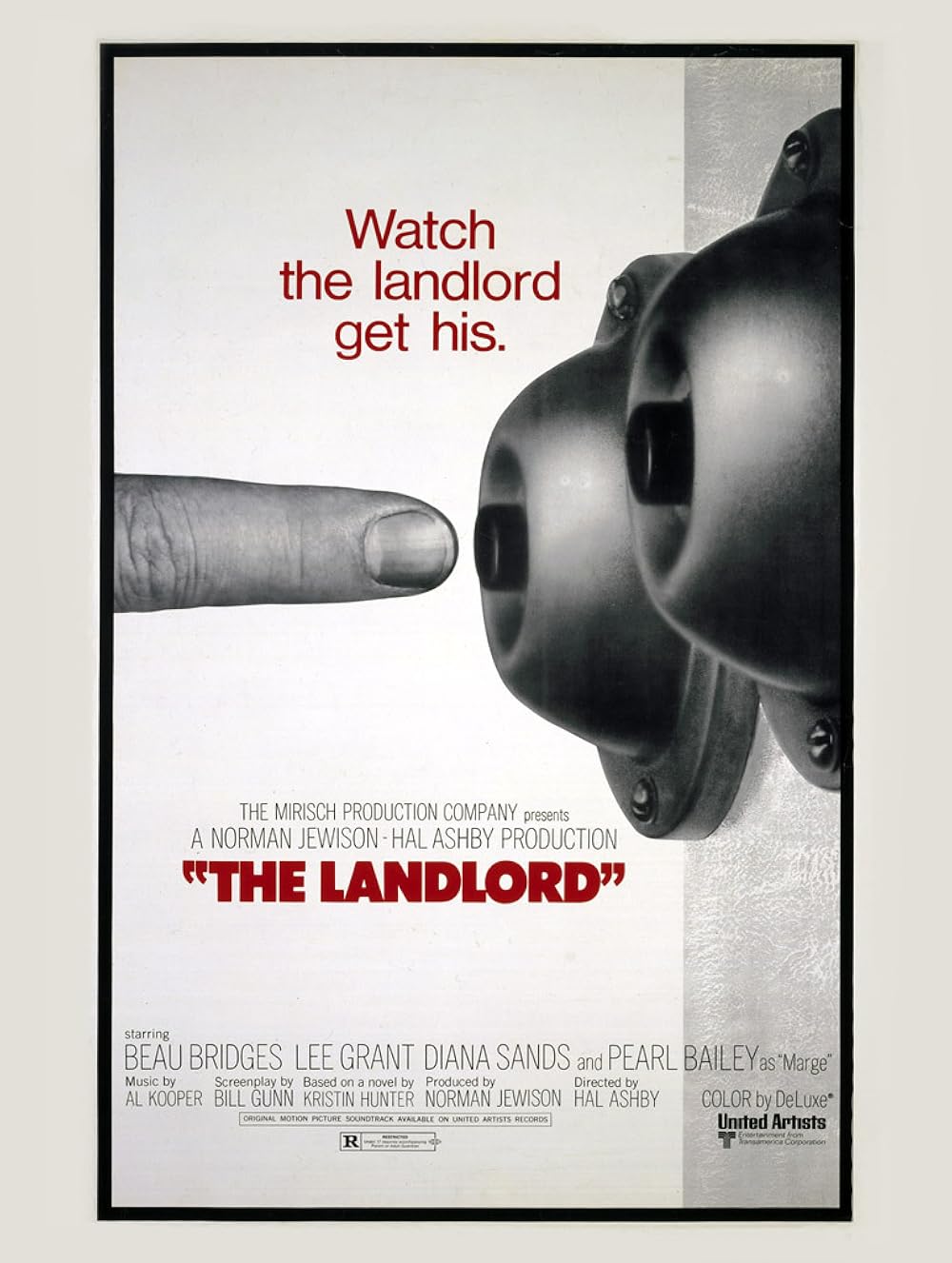

The Landlord: White Boy Woke Up

It takes a certain kind of person to wake up one day and decide he wants to be deep. Not just rich or clever or free. He wants to be conscious. So, he runs away from home and thinks maybe if he tries hard enough, then he will be a better person. I watched The Landlord not expecting much, but it managed to get stuck in my mind long after it ended. It’s strange how a film from a country not your own can be an uncanny mirror. I, too, ran away from my home because I wanted to make a better life for myself. Of course, it was to escape a war-torn nation, but the feelings are the same. Stepping cluelessly into an unfamiliar culture should not be taken lightly.

Hal Ashby’s directorial debut is humorous, painful, and all too real. The film follows a rich white man named Elgar Enders (played by Beau Bridges) who buys an apartment block in a poor Black neighborhood in Brooklyn. He wants to renovate it, make it fancy for himself, and push out the tenants, but what he finds is they are proud, angry, funny, and most importantly, human. Of course, the tenants do not leave. This is where the real movie starts.

You don't see this every day.

Honestly, I didn’t hate Elgar. Is he clueless? Yes. Is he a tourist in the struggles of his tenants? Absolutely. But as the movie goes on, he does something that I have never seen a white character do in a story like this. He listens. He also sleeps with a Black tenant and knocks her up, but to his credit, he sticks around. This isn’t revolutionary, but it deserves some recognition. He has his human moments and that is what makes this movie feel real.

The beauty of this film is that it walks a tricky line, wanting to criticize Elgar and the entire rotten system that created him, but also to cheer his awakening. Sometimes it feels like watching a rich man go on a spiritual safari through Black suffering just to find himself, but we are quickly reminded that even white people get exiled when they go too far. He returns to his rich family and merely expresses empathy for his tenants and is met with cold disapproval and outright horror. No one is safe from being rejected. Not even family.

Dressed for a spiritual safari

It really hits home seeing the way Black and white America orbit each other in this movie. They are close enough to clash, yet never close enough to connect. As an immigrant, I recognize that tension. I have lived in those in-between spaces where I am too foreign for one side and invisible to the other. Lanie (played by the beautiful Marki Bey), the woman that Elgar falls in love with, is an attempt to bridge that gap. She is mixed race and light skinned enough to pass as white. Though their story is complicated and does not end in the usual romantic way, it feels honest. It doesn't pretend by forcing everyone to hold hands and sing at the end. It’s not entirely clear how this relationship moves forward, but I think that is also true of the relationship between Black and white America.

"You think I'm white don't you?"

The Landlord is not perfect. It tries to be funny and serious at the same time, and sometimes it stumbles. What is important is that it tries. It looks at race and class without pretending to have answers. It shows how people get hurt even when no one means to cause harm. It does not preach. It shows. It lets you feel. For me, that’s the best kind of art.

I walked away thinking this movie matters. Not because it solves anything, but because it refuses to look away. It points the camera at something that most people would rather turn a blind eye to or forget; that race and class in America are not just about violence and protests. They are about property, who owns it, who lives in it, and who gets thrown out. For all its flaws, The Landlord tries to have that conversation with humor and messiness. I think about my own future when I watch this movie. Maybe one day I will have a place here too. We all deserve to belong where we are.

4 out of 5 stars

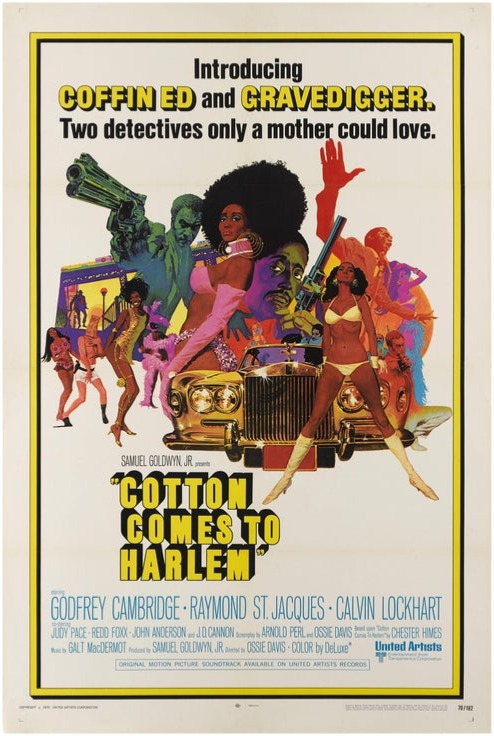

Cotton Comes to Harlem: A Joke Without a Punchline

What was Cotton Comes to Harlem trying to do? All I got from it was confusion, noise, and a movie that couldn’t decide what it wanted to be. It was supposed to be a comedy. Maybe even a smart one. But the longer I watched, the more I felt like I was waiting for a punchline that never came.

The film follows two Harlem detectives, Gravedigger Jones (played by, again, Godfrey Cambridge) and Coffin Ed Johnson (played by Raymond St. Jacques), chasing down a bale of cotton that is hiding nearly $90,000 stolen from poor Black families by a conman preacher. Money that is scammed from the community with promises of a return to Africa. That setup could have led to something sharp and powerful: Black liberation, exploitation, identity, the hypocrisy of a hustler that uses language to empty people’s pockets. There is room here for satire, for anger, even for real laughs, but instead, the movie can’t decide what it is. Some parts play like gritty police drama. Others feel like something out of a cartoon. I kept asking myself, “is this supposed to be funny or am I missing something?”

What is the narrative here? Crime featuring Black vs. Black?

Because this film plays like a buddy cop drama that got awkwardly spliced together with a Saturday morning cartoon. One minute there’s a serious conversation about exploitation; the next there’s a man dangling from a crane with his underwear showing. The music tells you it is a comedy, but the performances say otherwise. It’s hard to laugh when you don’t know if you’re supposed to.

The two main characters could have carried the film if they had more to work with. Gravedigger and Coffin Ed are supposed to be cool, no-nonsense detectives, but we barely learn anything about them beyond their toughness. I had to check the credits just to get their names. There is no emotional core here—just scattered scenes of fighting, chasing, and incomplete jokes.

I found myself trying to locate punchlines. To understand what was being critiqued and how, and what really frustrates me is how often the movie hints at something deeper. A scam built on the backs of Black hope? That could have been a powerful blow, but every time the movie touches something real, it pulls back and throws in a silly gag…that scarcely draws a chuckle. It’s as if it’s afraid to say anything poignant.

I don't think even they know what's going on here?

As an immigrant, I’ve seen how people get taken advantage of by slick talkers promising a better life. I understand how easy it is to be conned by flowery language and a plausible grift. It’s not so easy to say no to someone being polite when your culture raises you to respect your elders and authority. I recognize the hunger for dignity and how easy it is for someone to sell you a dream that turns into dust. I wanted this film to get to that. To deliver on that point. For someone to feel that. But it sends no clear message and as a result, it makes no point.

You can't pull a fast one on me.

I’m not against mixing comedy and social commentary, but Cotton Comes to Harlem doesn’t mix them. It smashes them together and hopes something comes of it. For me, it didn’t work. A good idea buried under a movie that never figures out how to tell the story… or the joke, I walked away more confused than entertained.

1 out of 5 stars.

In the end, Watermelon Man, The Landlord, and Cotton Comes to Harlem create a narrative around the same wound, one that digs into how race, power, and belonging shape life in America. Each of these films carve their own path because we need more diverse voices. Watermelon Man kicks and screams and demands to be heard, The Landlord softly asks questions using a white face in Black surroundings, and Cotton Comes to Harlem cracks jokes and hopes that the message lands somewhere amidst the laughter. They don't all succeed, but they do share the same desire to expose America to the absurdity and cruelty of American racism. Whether the message is delivered by satire, sincerity, or stumble, each film shares with us the same message: this story ain't over, and even if it sometimes tries to make you laugh, it sure as hell ain't funny.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

![[June 14, 1970] Talkin' Loud, Swingin' Soft (June 1970 <i>Watermelon Man, The Landlord, and Cotton Comes to Harlem</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700614movies-672x372.jpg)

![[May 12, 1970] War and Peace (June 1970 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/COVERSMALL-672x372.jpg)

![[March 26, 1970] A Quartet of Whimsy (<i>Satyricon, Skullduggery, Horton Hears a Who, Necropolis</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700324cinemascope-672x372.jpg)

![[March 14, 1970] <i>To Venus</i> and <i>Hell's Gate</i>… are we <i>Out of Our Minds</i>?](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700314covers-672x372.jpg)

![[March 6, 1970] <i>The Waters of Centaurus</i>, <i>And Chaos Died</i>, and <i>High Sorcery</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700306covers-672x372.jpg)

![[January 28, 1970] Cinemascope: Just a Poe Boy (<em>An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe</em>, <em>The Moebius Flip</em>, </em>Sole Survivor</em>, and <em>The Dunwich Horror</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/12970-an-evening-of-edgar-allan-poe-0-460-0-690-crop-2830000383-460x372.jpg)

Theatrical poster for An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe

Theatrical poster for An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe

The Sphinx

The Sphinx The Pit and the Pendulum

The Pit and the Pendulum The Tell-Tale Heart

The Tell-Tale Heart

![[January 10, 1970] Time On My Hands (February 1970 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/COVER-672x372.jpg)

![[December 22nd, 1969] Safety On! (<i>I Sing the Body Electric!</i> by Ray Bradbury)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Bradbury-Cover-595x372.jpg)

![[November 8, 1969] Arabesques (December 1969 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/COVERARTSMALL.jpg)

![[September 16, 1969] September 1969 Galactoscope](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/690916covers-672x372.jpg)