by Victoria Silverwolf

P.O.P. Sends Out An S.O.S.

The seaside amusement area known as Pacific Ocean Park, opened in 1958, closed its doors forever a couple of days ago, due to decreasing attendance and failure to pay back taxes and rental fees.

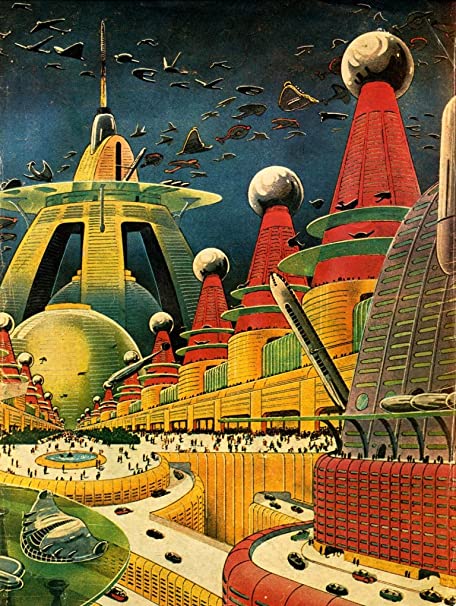

Pacific Ocean Park in happier days.

This aquatic rival of nearby Disneyland offered such futuristic and nautical delights as the House of Tomorrow, a Sea Circus, Diving Bells, the Sea Serpent Roller Coaster, and even a Flight to Mars, to name just a few out of dozens.

Artist's impression of the entrance to the defunct wonderland.

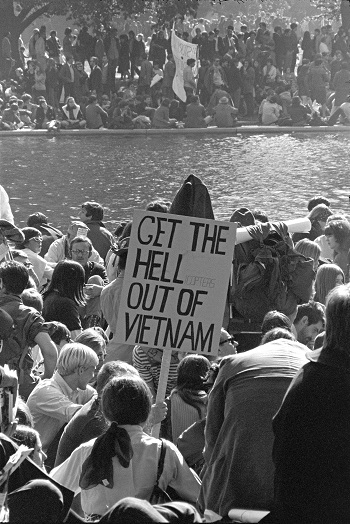

Long Time Passing

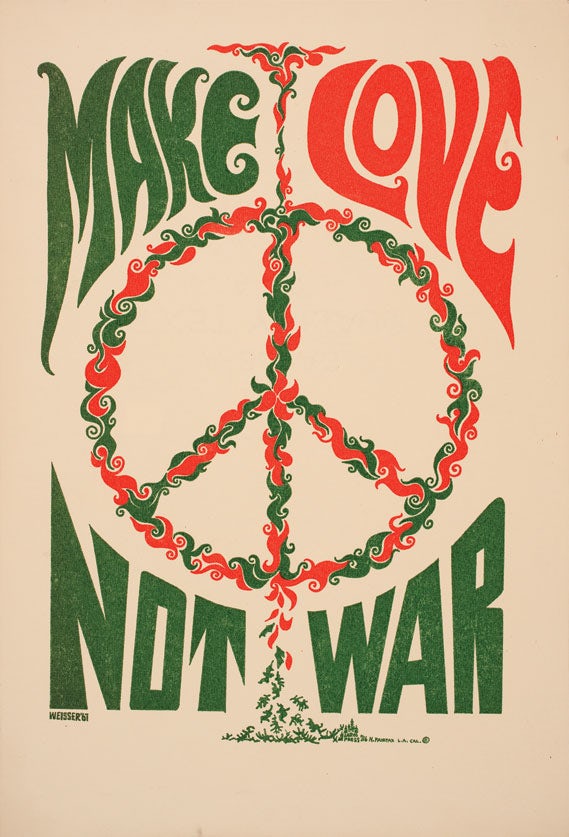

The vanishing of this Southern California landmark brings thoughts of the way in which almost everything disappears sooner or later. Pete Seeger's classic folk song Where Have All the Flowers Gone? (perhaps best known in the version recorded by Peter, Paul, and Mary a few years ago) could serve as appropriately melancholy background music for such meditations.

It's on the trio's first album, by the way.

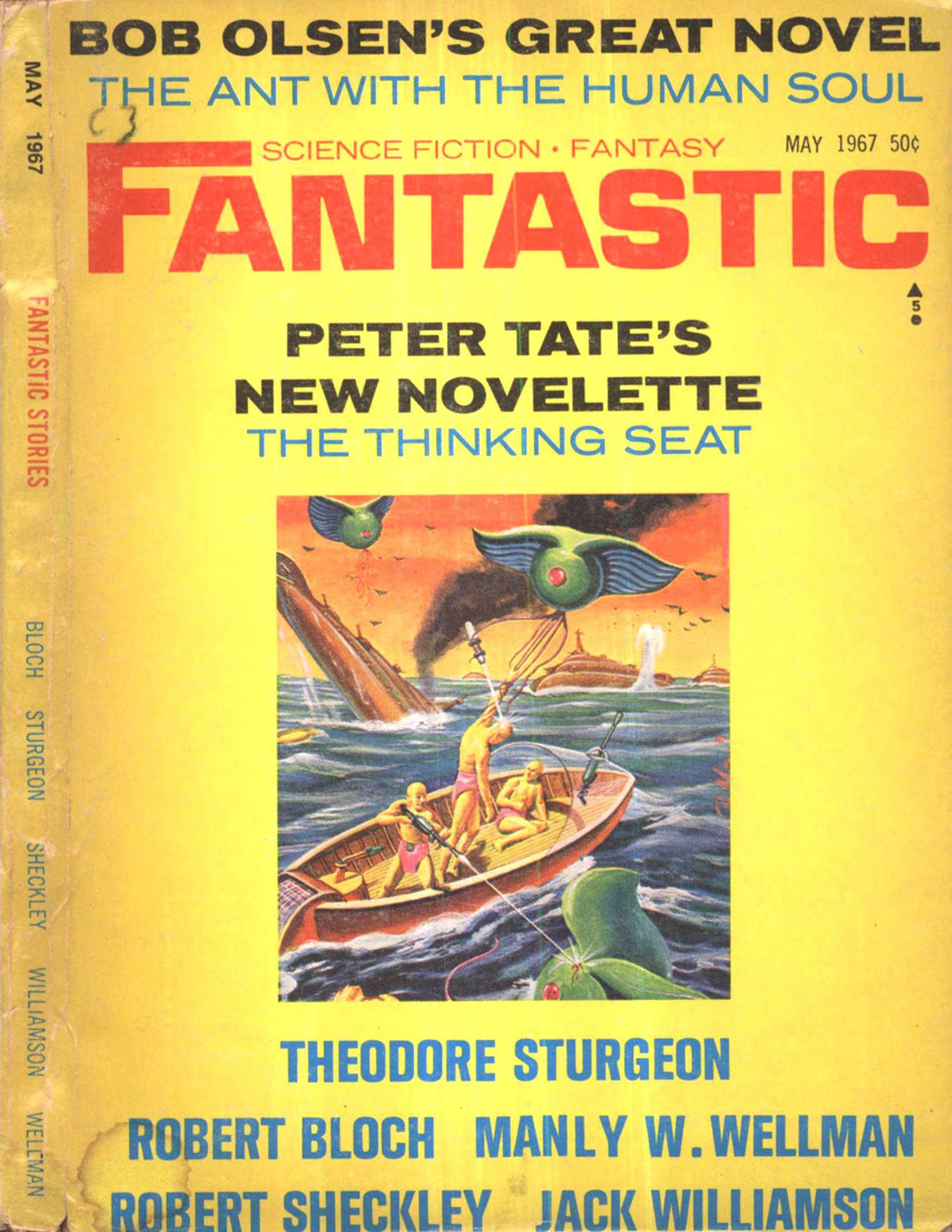

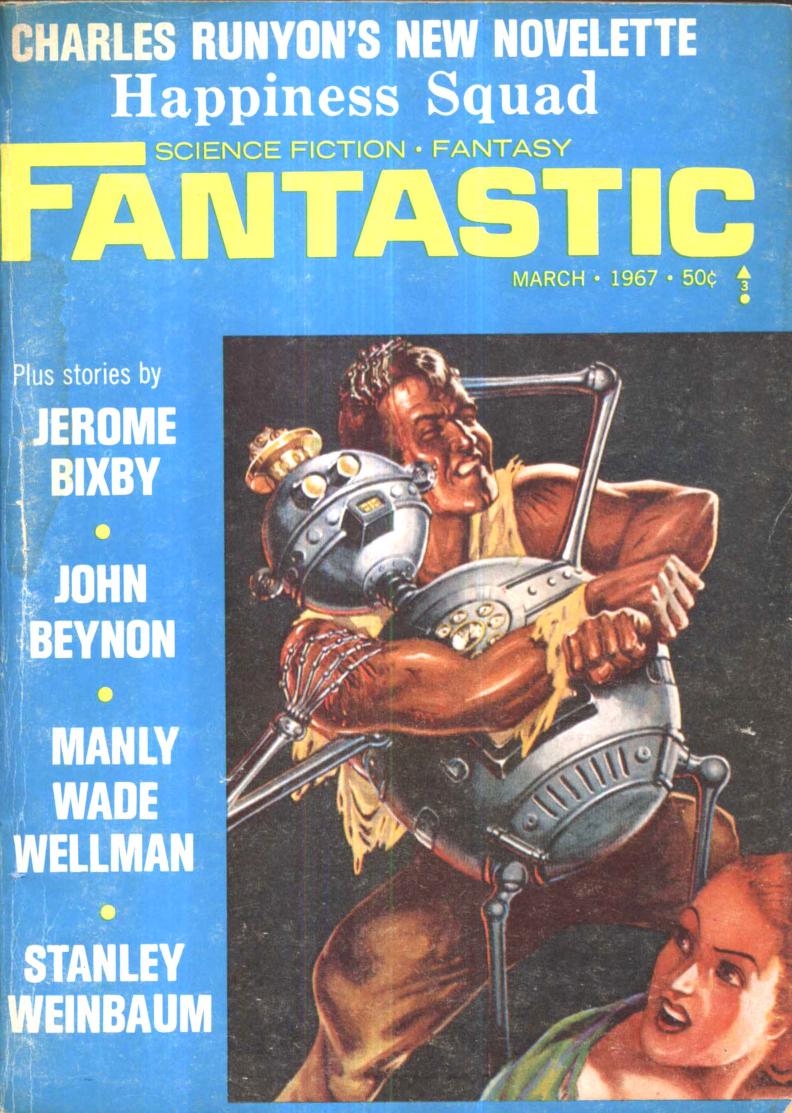

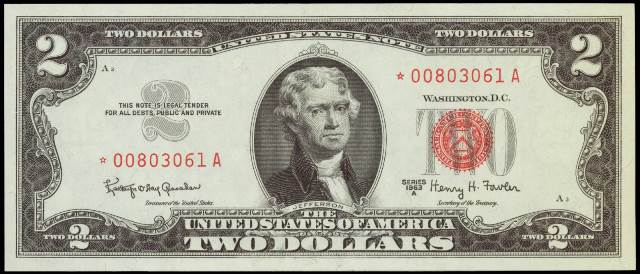

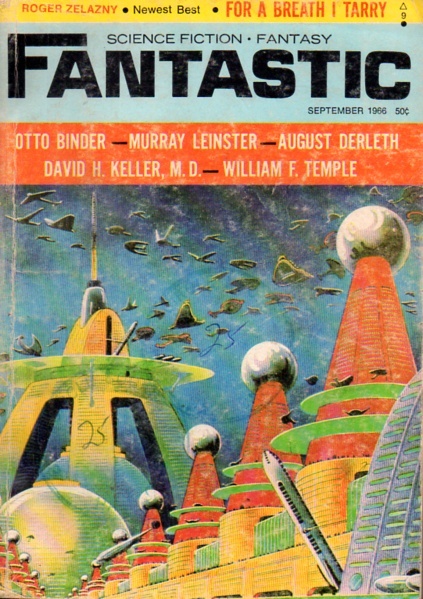

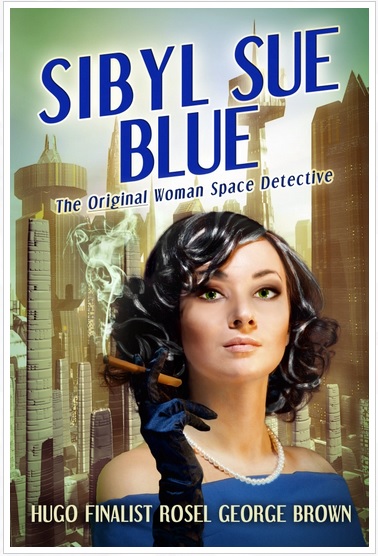

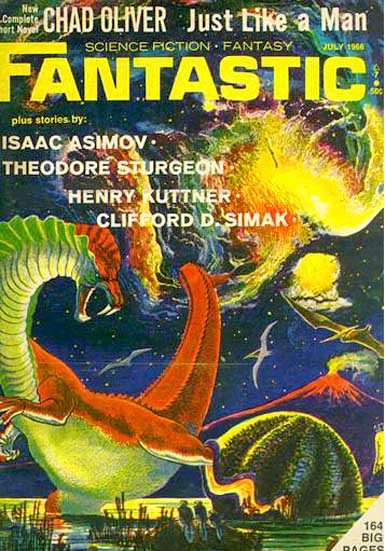

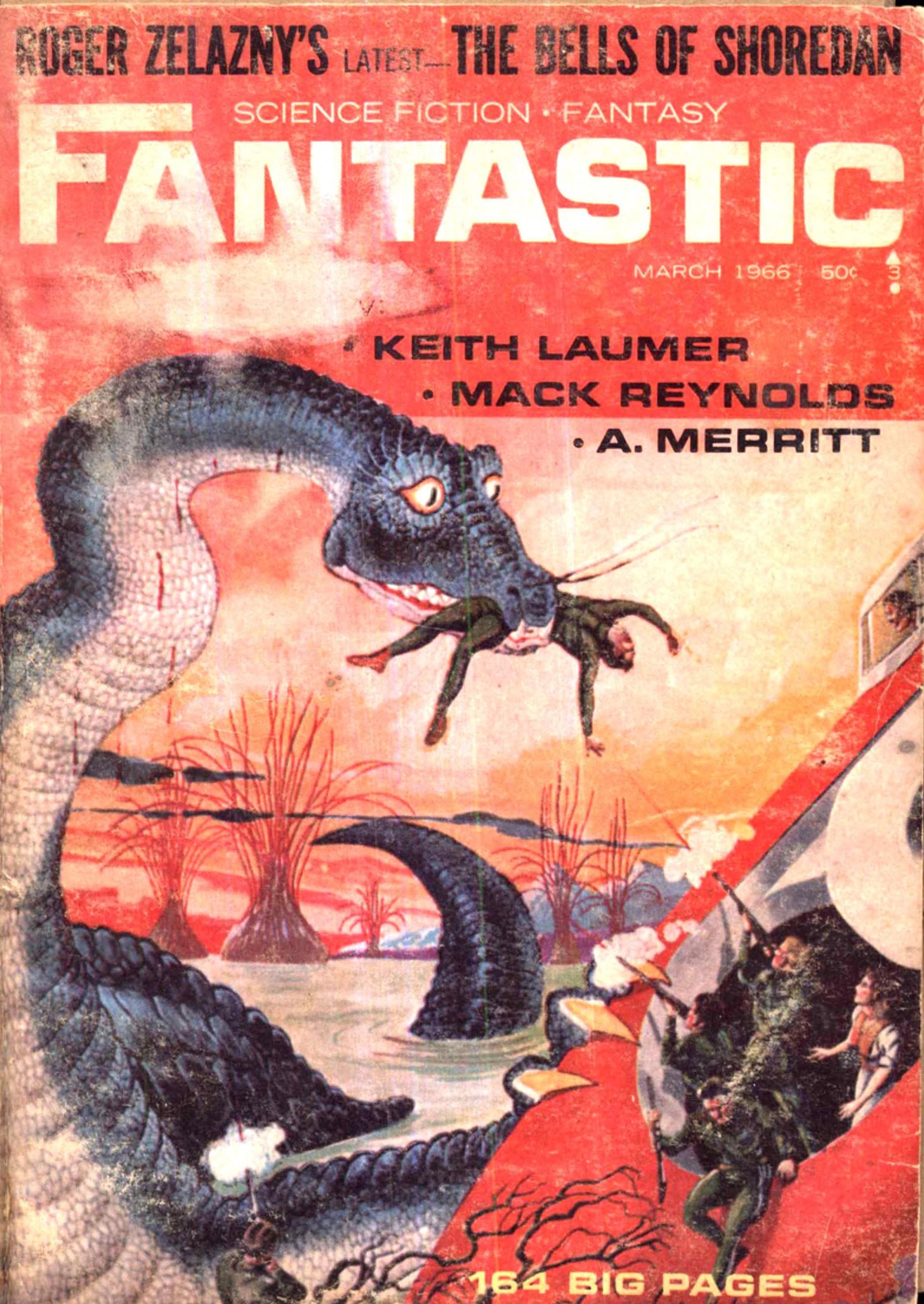

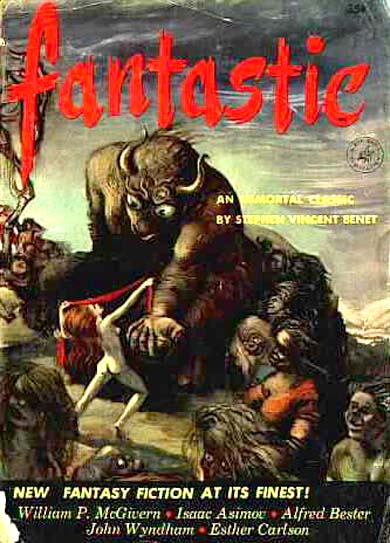

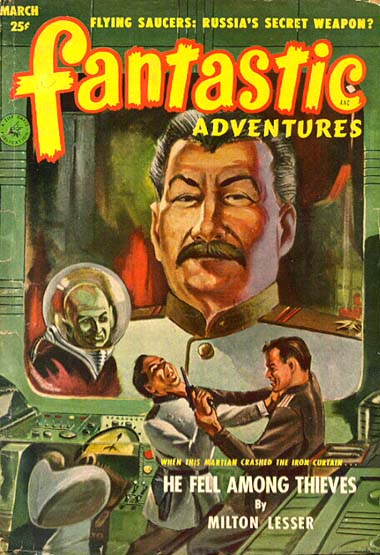

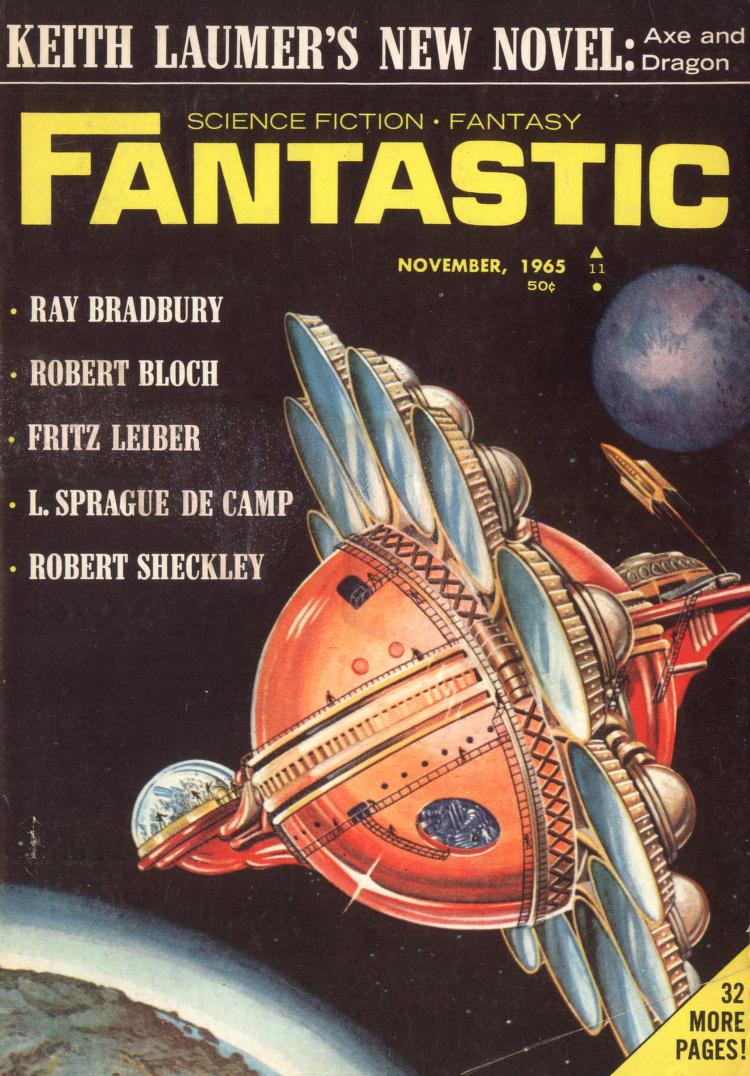

Appropriately, the latest issue of Fantastic contains a number of stories dealing with the passage of time and the decay of technology and culture.

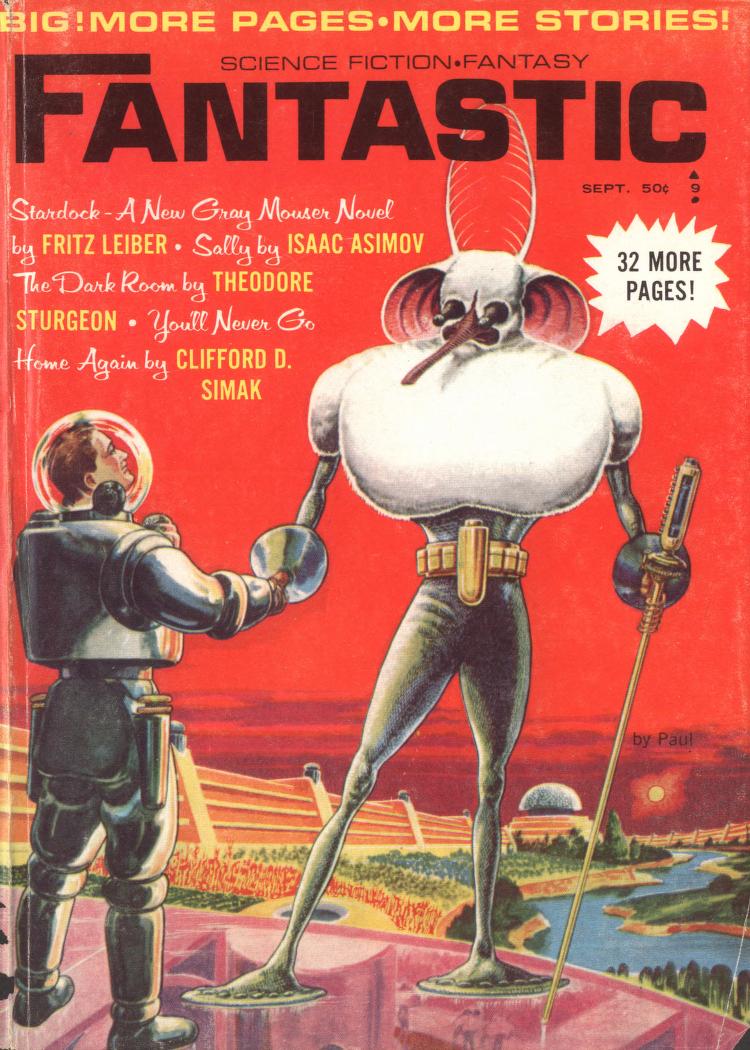

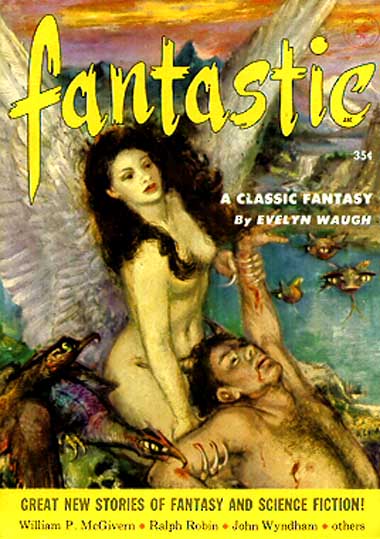

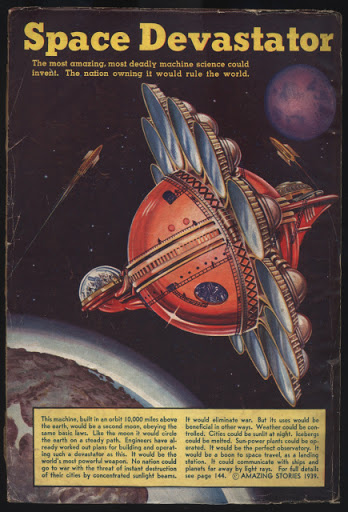

Recycled art by Johnny Bruck.

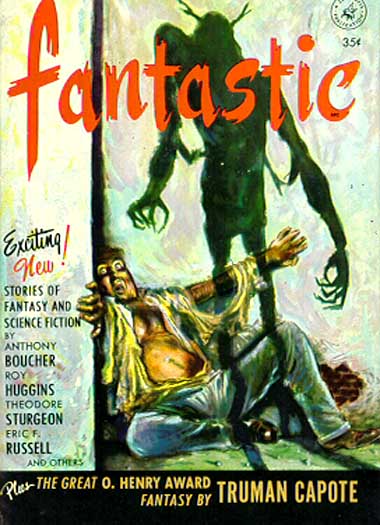

The painting on the cover, as usual, has already appeared elsewhere. In this case, it's from an issue of Perry Rhodan, the popular weekly German publication named for the heroic space adventurer who appears in its pages.

Working from a German/English dictionary, the caption seems to mean something like Robots Please Allow . . . Far Is The Way To Noman's Land — A New Arlan Story. I'm sure my German-speaking fellow Galactic Journeyers can supply a better translation.

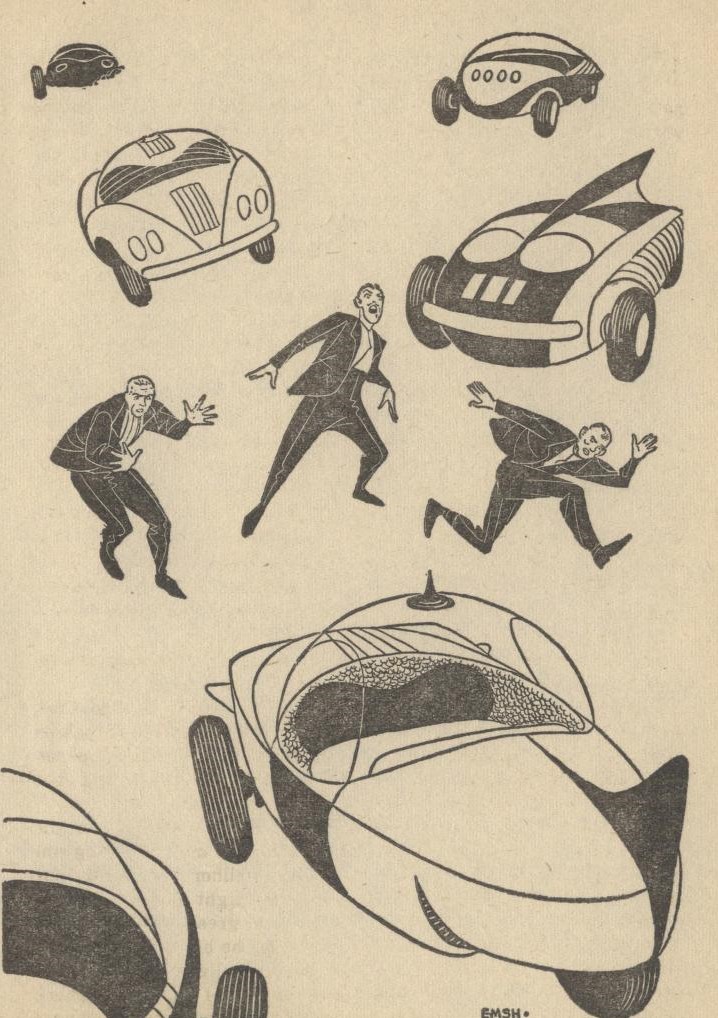

The Housebreakers, by Ron Goulart

Before we get to all the doom and gloom stuff dealing with vast expanses of time and the breakdown of society, let's have a little comic relief from a writer who specializes in funny stuff. If nothing else, it's the only new story in the issue.

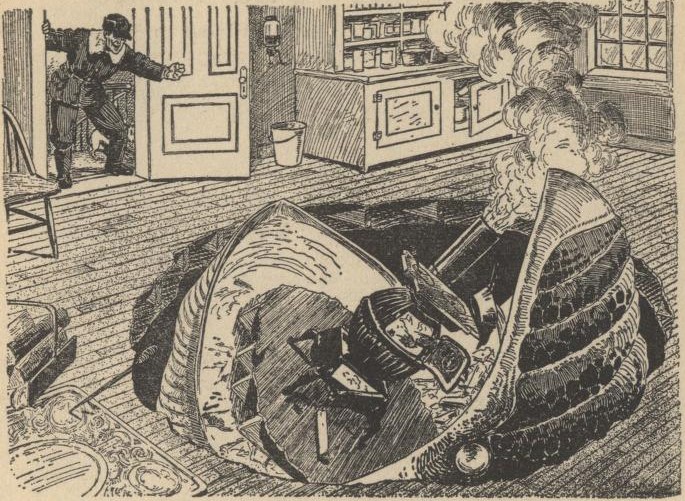

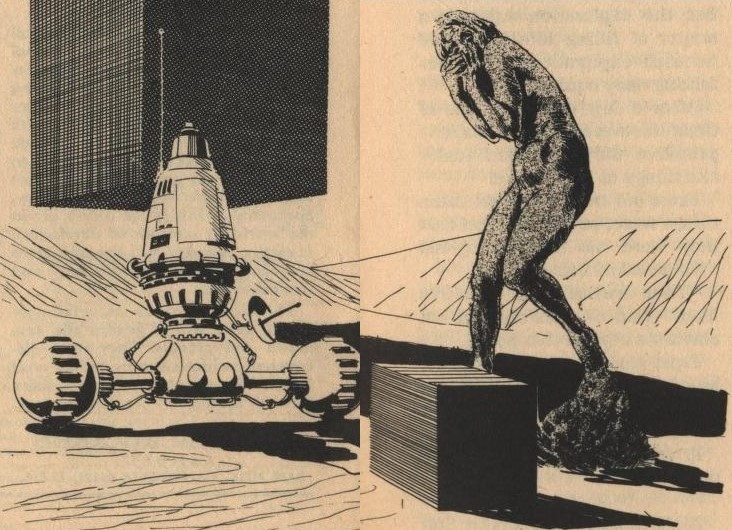

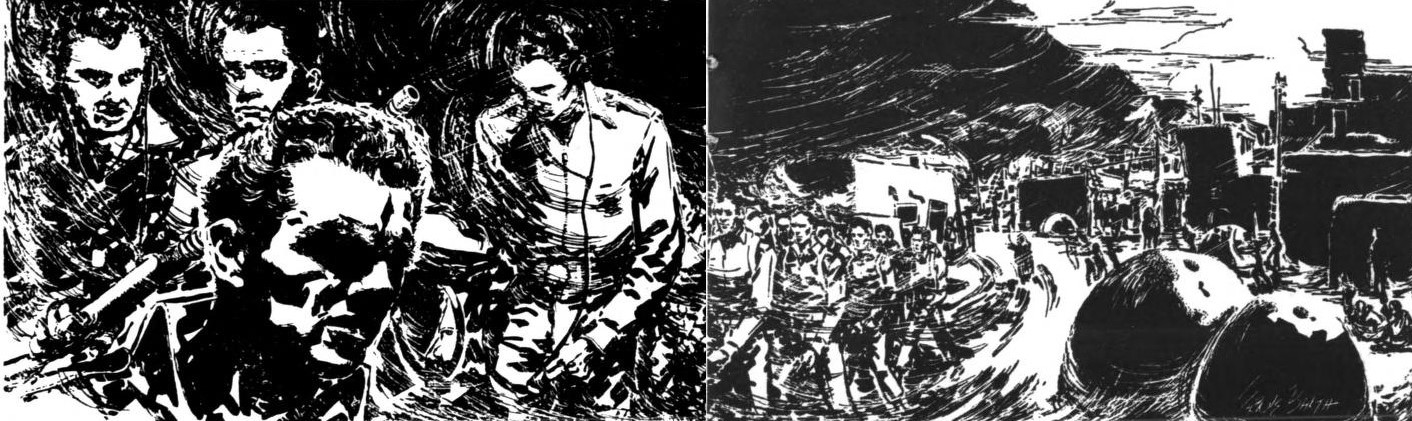

Illustrations by Jeff Jones.

A mercenary gets his latest assignment from a talkative computer riding in an unreliable automated car. It seems there's a planet that essentially serves as a suburb. Folks commute from it to other planets to work. Some of the inhabitants are criminals and other lowlifes dumped there. (That seems like a really bad idea to me, but it sets up the plot.)

Crooks are appearing out of nowhere, grabbing loot and then disappearing. Since they don't have the gizmo necessary for teleportation, this seems impossible. The last guy to investigate the case is missing in action and presumed dead. Our hero has to contact the wife of a fellow who has joined the robbers in an attempt to track them down. Could it have anything to do with the planet's only real city (as opposed to bedroom communities), thought to be abandoned?

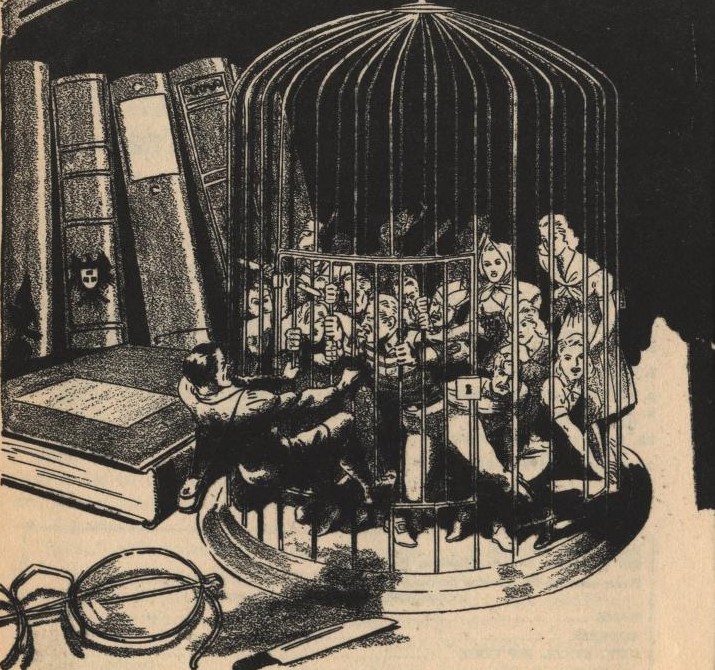

And what about this guy?

Maybe this sounds like crime fiction or an adventure story, but it's almost pure slapstick. There's not a lot of plot logic. The bad guys show up on horses, which doesn't make any sense in this high-tech setting. I guess the author wanted to spoof Westerns. The explanation for teleportation without a device is completely anticlimactic. Without giving too much away, it boils down to plot convenience.

Two stars.

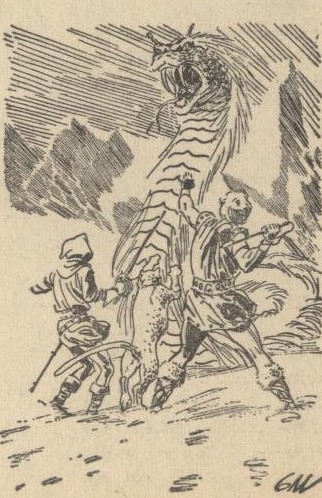

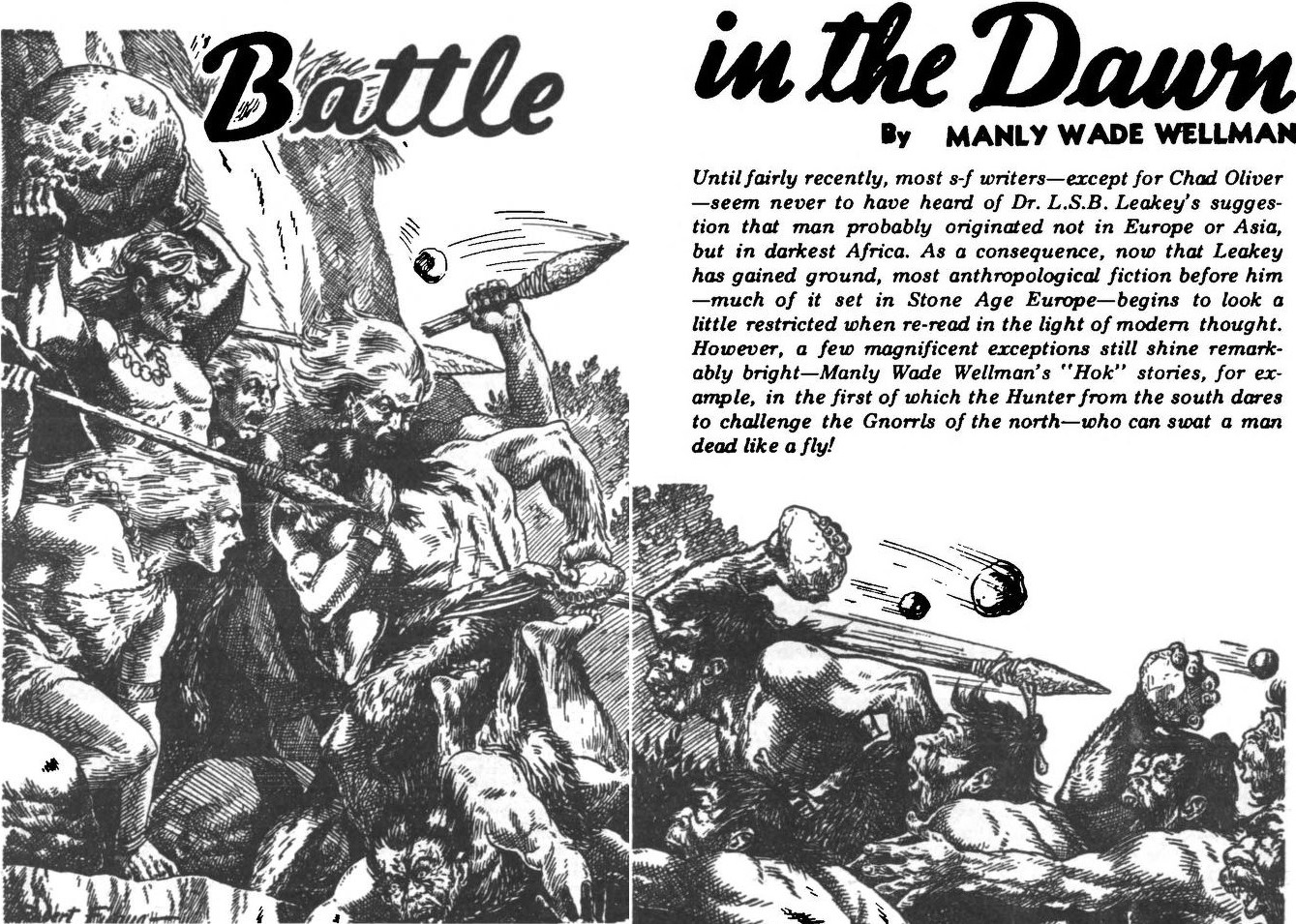

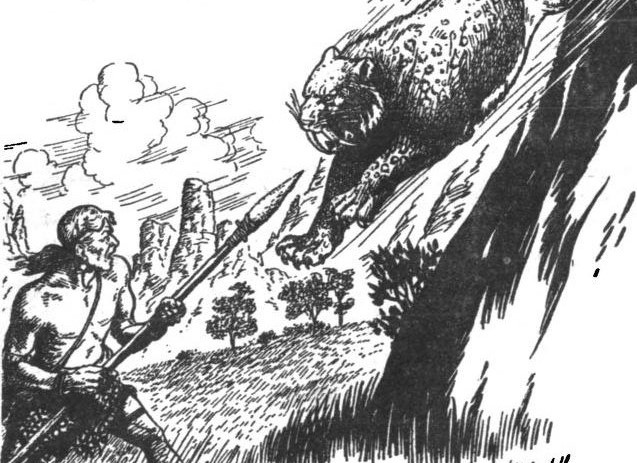

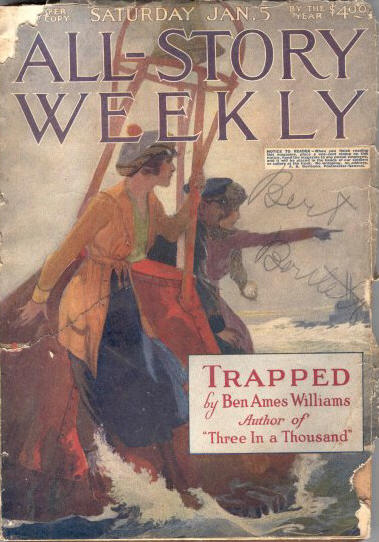

Hok Visits the Land of Legends, by Manly Wade Wellman

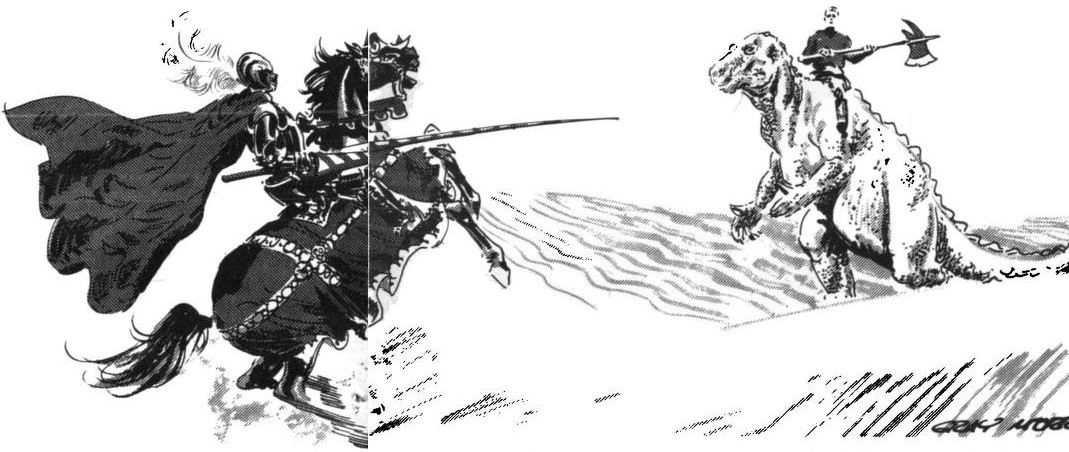

Illustrations by Jay Jackson.

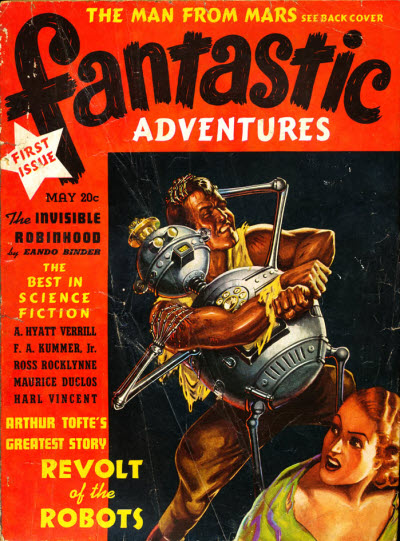

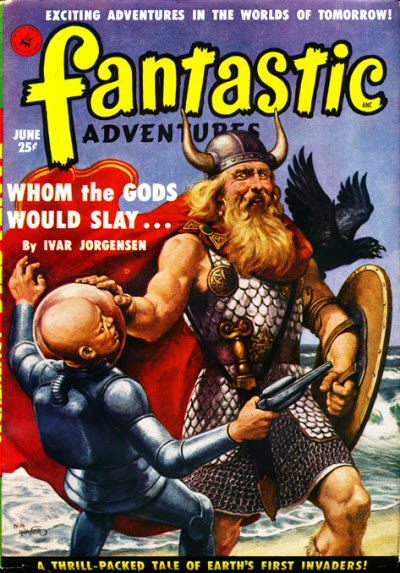

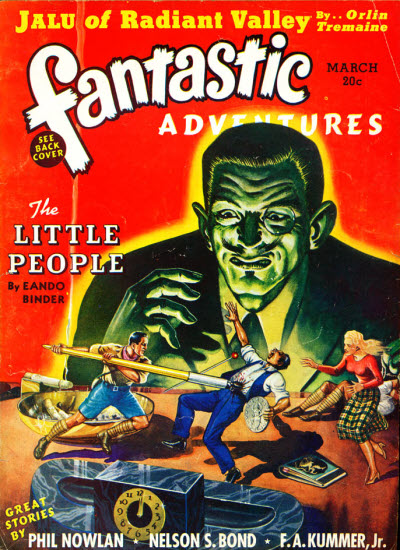

Speaking of vast amounts of time, let's go way, way back to the Stone Age. We've met the mighty caveman Hok a couple of times before. This yarn comes from the April 1942 issue of Fantastic Adventures.

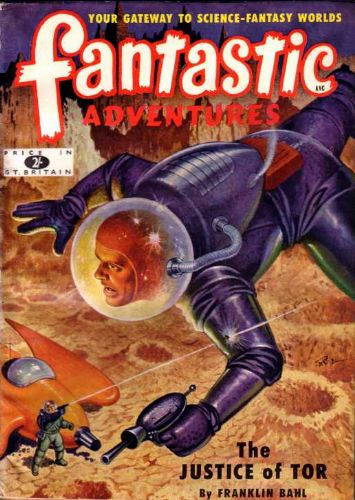

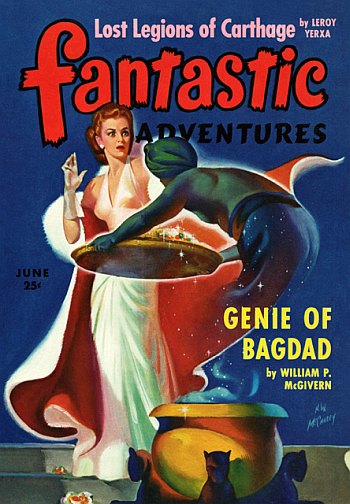

Cover art by Malcolm Smith.

Hok decides to kill a mammoth all by himself. He manages to wound the beast badly, and track it down through heavy snow to its place of dying. (This is similar to the legend of the elephant's graveyard.)

Note the very modern-looking snowshoes.

This turns out to be a deep valley, where the weather is nice and warm. The first thing you know, Hok is attacked by a pterodactyl.

Yes, this is an extreme anachronism; but what's a few million years between friends?

He also has to fight off a nasty critter, sort of like a rhinoceros, that doesn't belong in his time either. Poetic license, I guess.

A tribe of folks live in the treetops of this hidden tropical jungle. They're ruled by a brutal dictator. Hok has to deal with this guy as well as the animals that are out to kill him.

Even more so than in previous stories in this series, it's impossible to take this outrageous tale as a serious look into the remote past. The hot weather in the valley, the presence of beasts that died out millions of years before humans showed up; none of it makes sense.

There are tons of footnotes, as if we're supposed to accept this as scientific speculation rather than pure fantasy. These get in the way of just enjoying an exciting adventure story. Perhaps the most unbelievable thing about this exercise in pseudo-scholarship is the notion that Hok is the source of legends about Hercules.

Two stars.

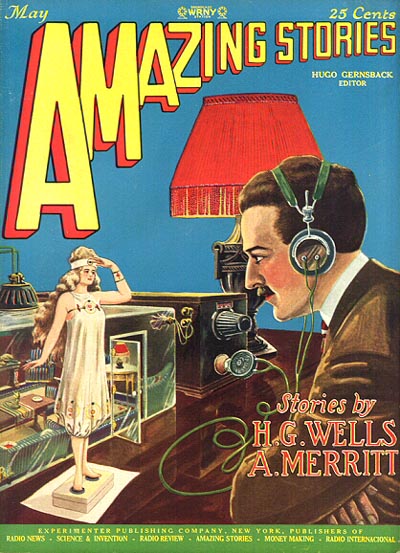

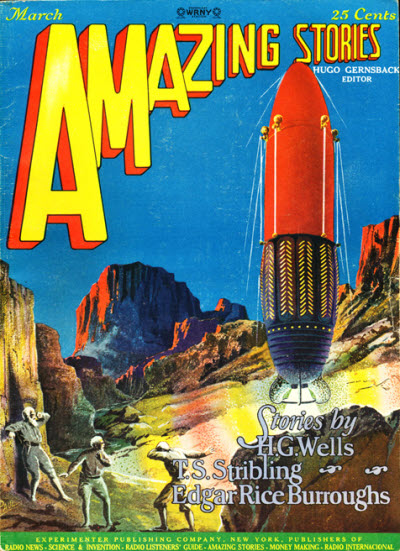

That We May Rise Again . . ., by Charles Recour

Illustration by Julian S. Krupa.

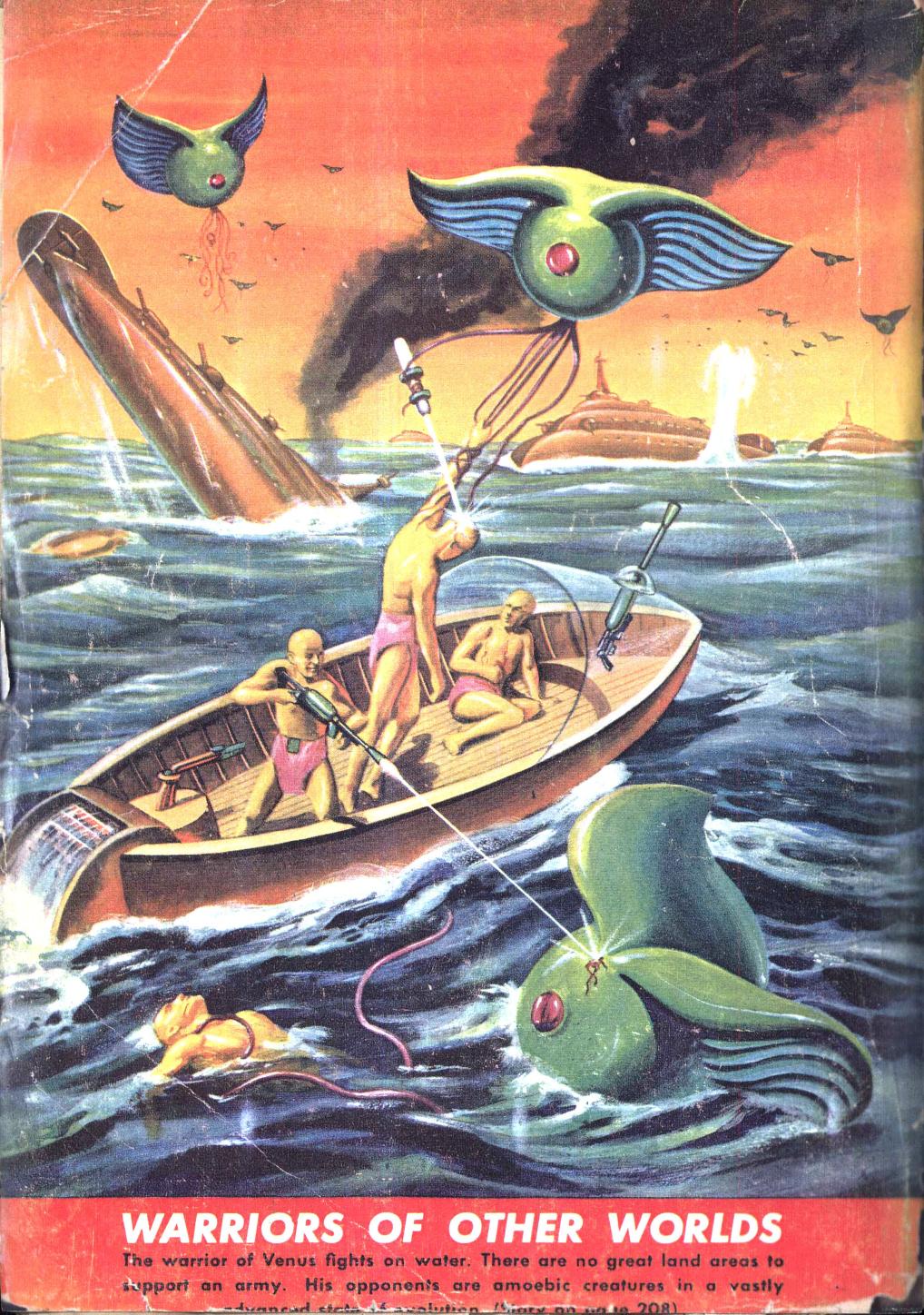

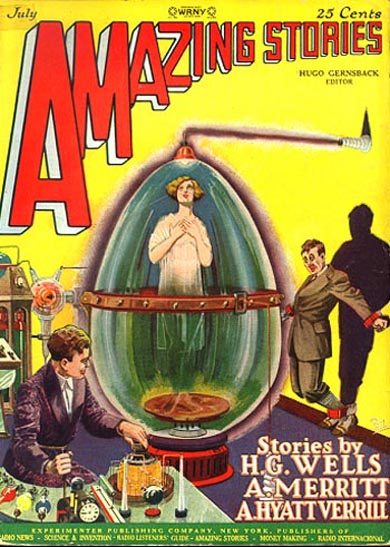

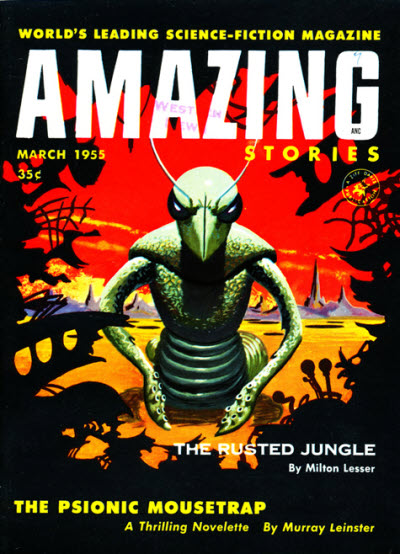

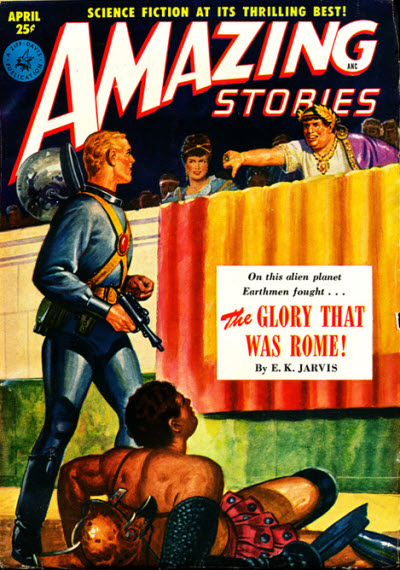

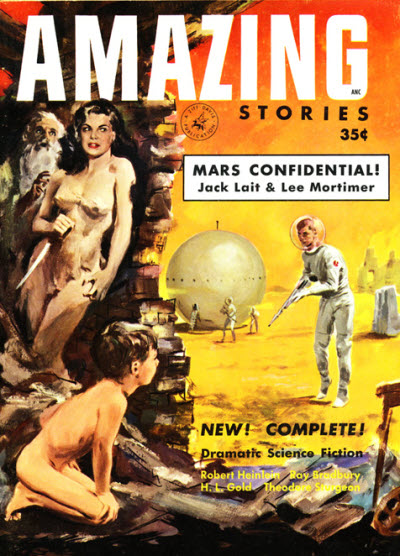

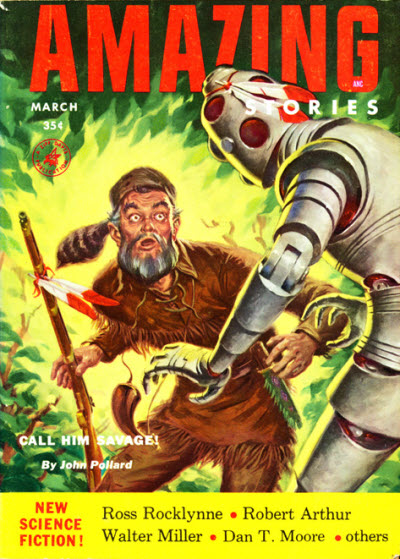

From the remote past we jump forward into the extreme far future, in this apocalyptic tale from the July 1948 issue of Amazing Stories.

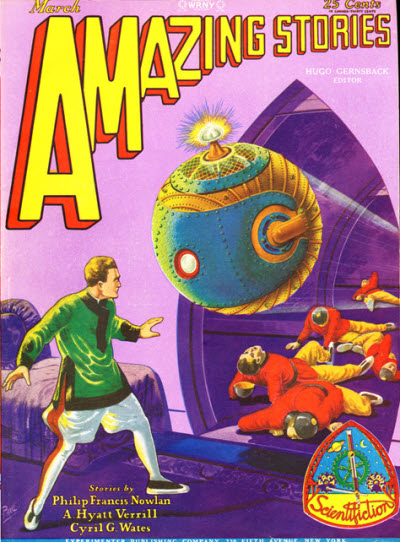

Cover art by Arnold Kohn.

A really long time from now, Earth is ruled by gigantic telepathic ants. They keep a few human beings around as servants. Our hero's master is a relatively kind ant, it seems. It lets him wander through a library of ancient books, learning how humanity used to dominate the planet. Apparently, the huge ants were created by radioactivity during the atomic war that destroyed civilization (The author anticipated the flick Them! by a few years.)

The ants want this fellow to take a ride in their only rocket ship, so he can act as a sort of double-check on their navigation systems. They don't want to go into space, but they want to take a look at things up there. Meanwhile, the guy meets the only other human being he's ever seen. Wouldn't you know it, she's a woman, and they fall instantly in love out of pure instinct.

Suddenly the prospect of taking a trip into the void doesn't sound so appealing. The lovebirds set out on their own, despite the opposition of the massive brain that rules over all the ants and their human slaves.

This is kind of a silly story that tries to create pathos in the fate of the two humans but winds up seeming ludicrous instead. The love story is implausible, to say the least, since these folks have never encountered one of their own kind before. It almost makes the giant ants seem realistic.

Two stars.

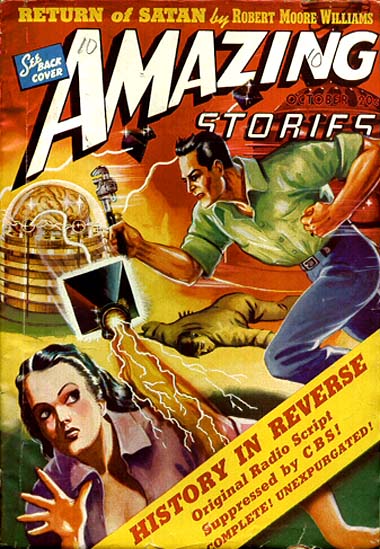

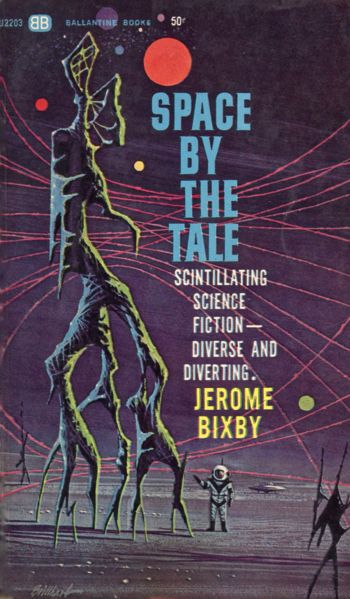

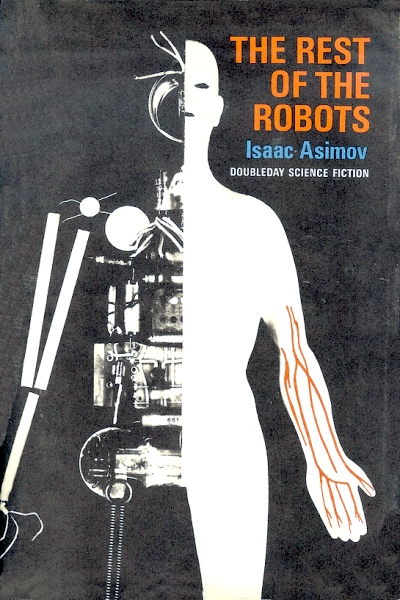

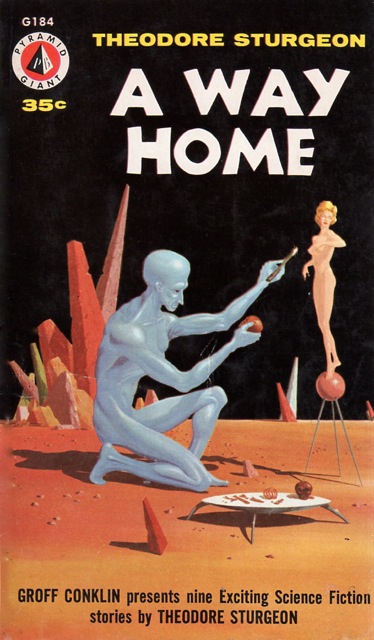

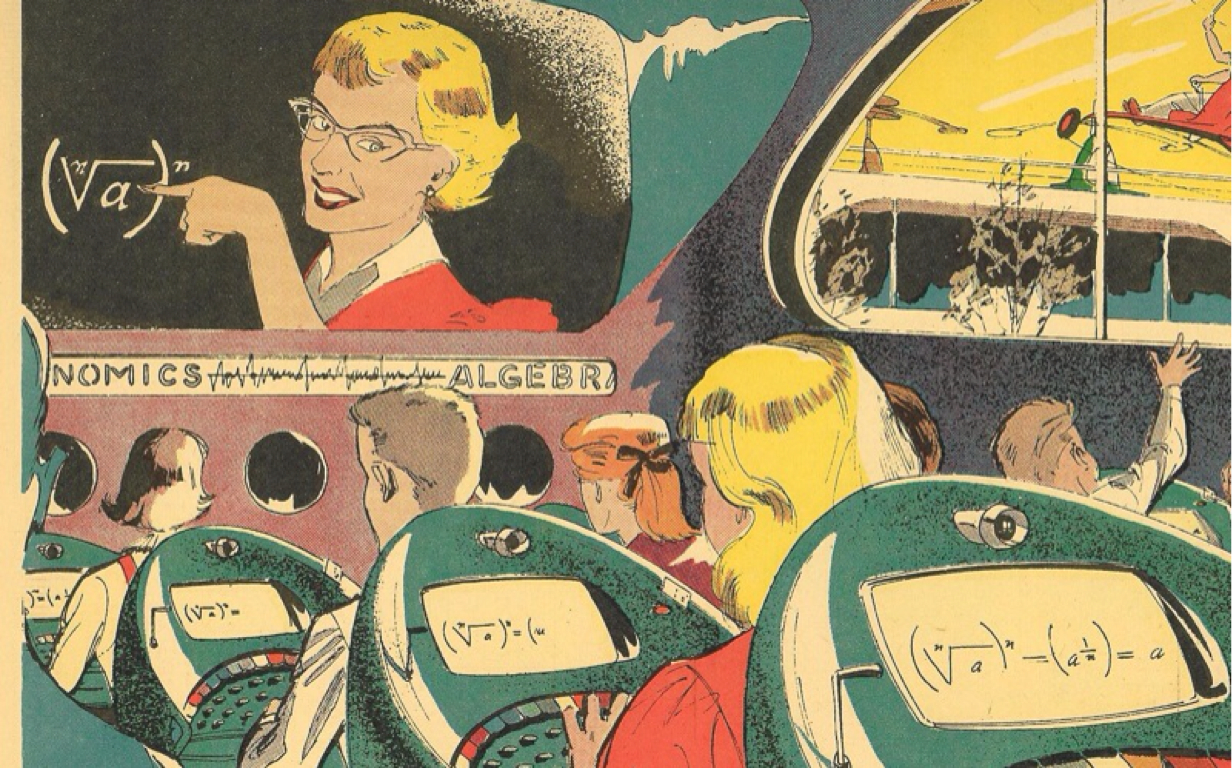

Make Room for Me!, by Theodore Sturgeon

Illustration by Gerald Hohns.

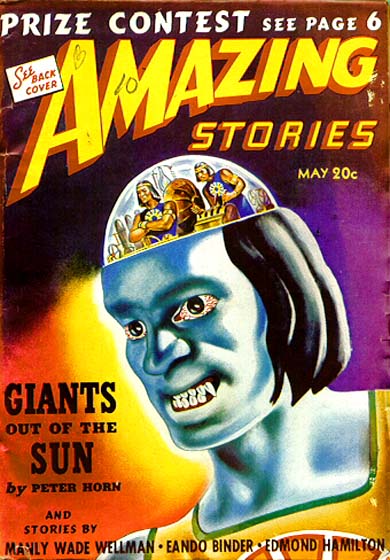

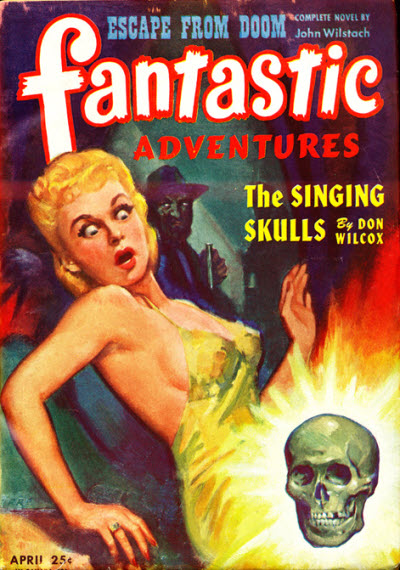

The May 1951 issue of Fantastic Adventures supplies this story featuring one of the author's favorite themes.

Cover art by Robert Gibson Jones.

As in his famous novel More Than Human (1953), Sturgeon presents us with a kind of group mind. Three college students form a triangular relationship. One, the only woman in the group, supplies the emotional and esthetic aspects of their lives. One of the men is an intellectual, and the other performs physical tasks. They drift apart over the years, but inevitably come back together. There's an unexpected reason for this.

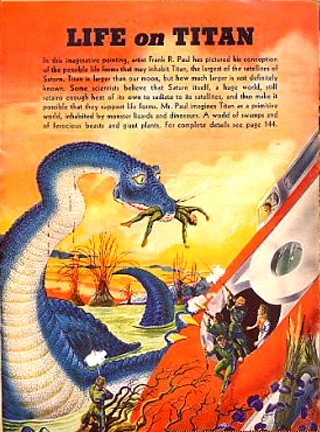

An alien who consists of three symbiotic parts inhabits their minds. Those of its species have been acting as mental parasites on the simple lifeforms on the moon Titan. Now they intend to move to Earth, because the creatures they prey upon are running out. Working as one, the humans come up with an alternate plan to benefit everyone.

Despite its rather melodramatic science fiction aspects, this is a moving account of people who find themselves drawn together mysteriously, often against their conscious wills. As you'd expect from Sturgeon, the characters seem like real, complex people. It may be something of a stereotype to have the only woman be the emotional member of the group, but this doesn't seriously detract from the story.

Four stars.

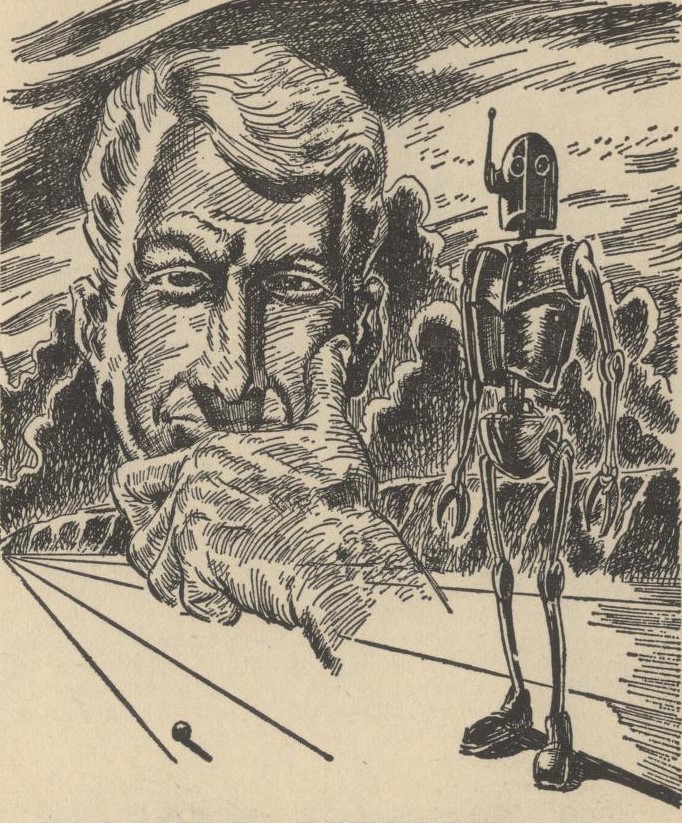

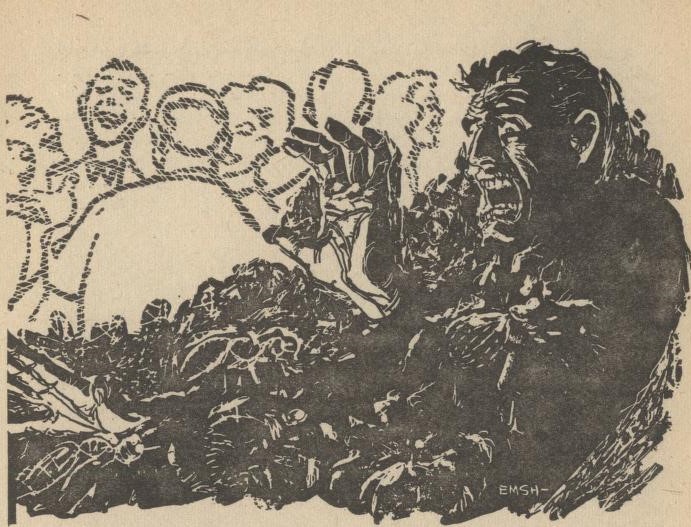

Full Circle, by H. B. Hickey

Illustration by Ed Valigursky.

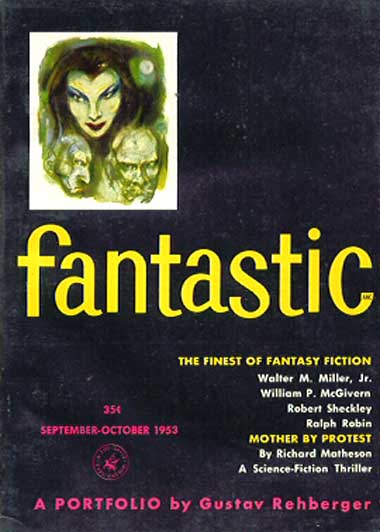

The premiere issue of the magazine (Summer 1952) is the source for this brief bit of irony.

Cover art by Barye Phillips and Leo Summers.

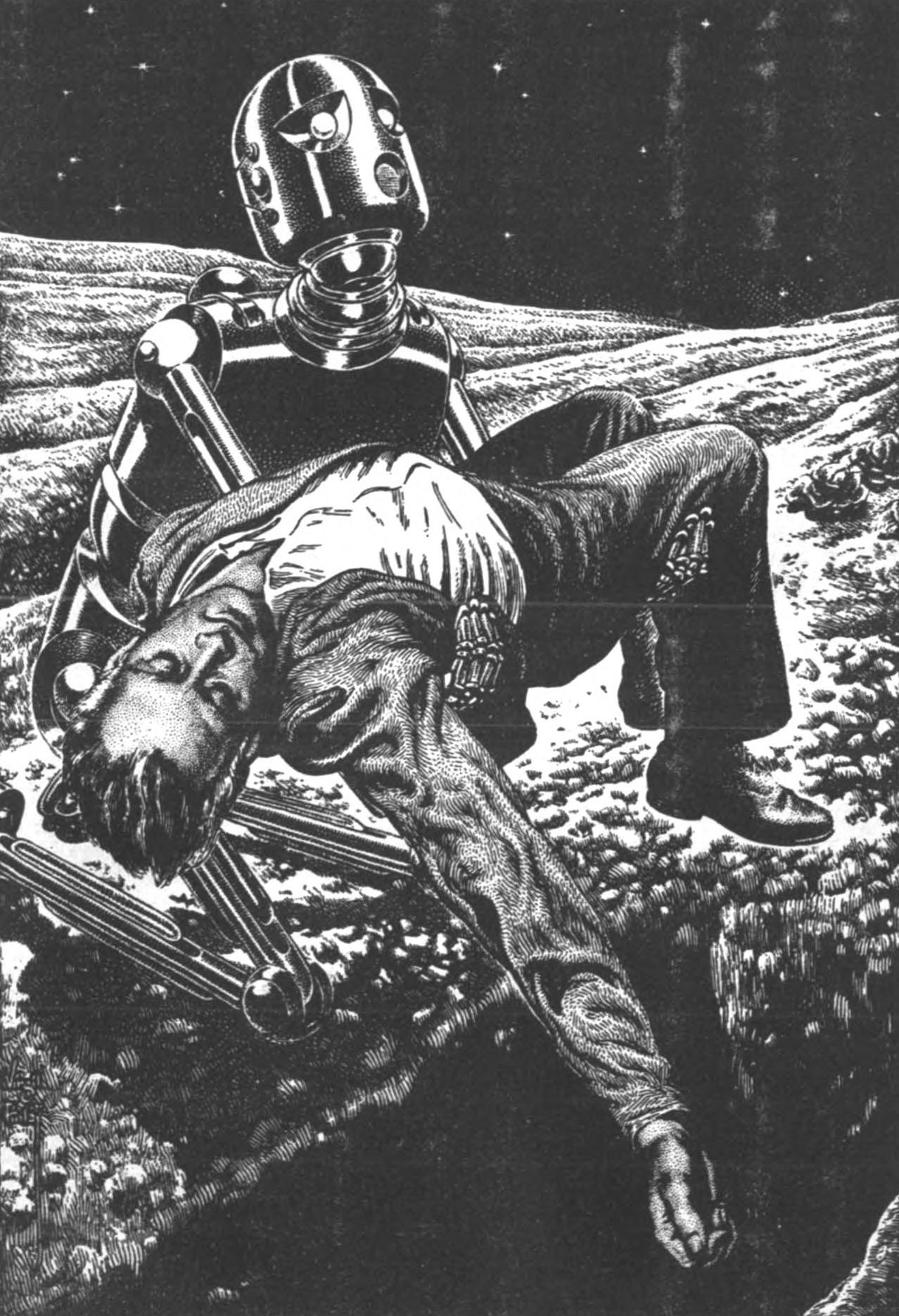

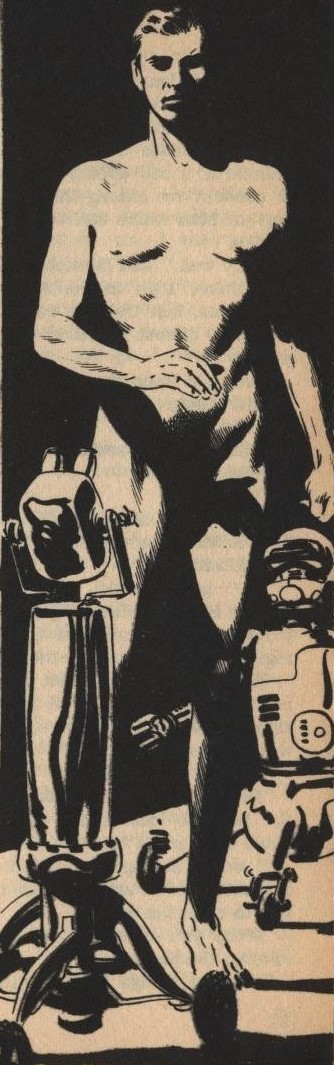

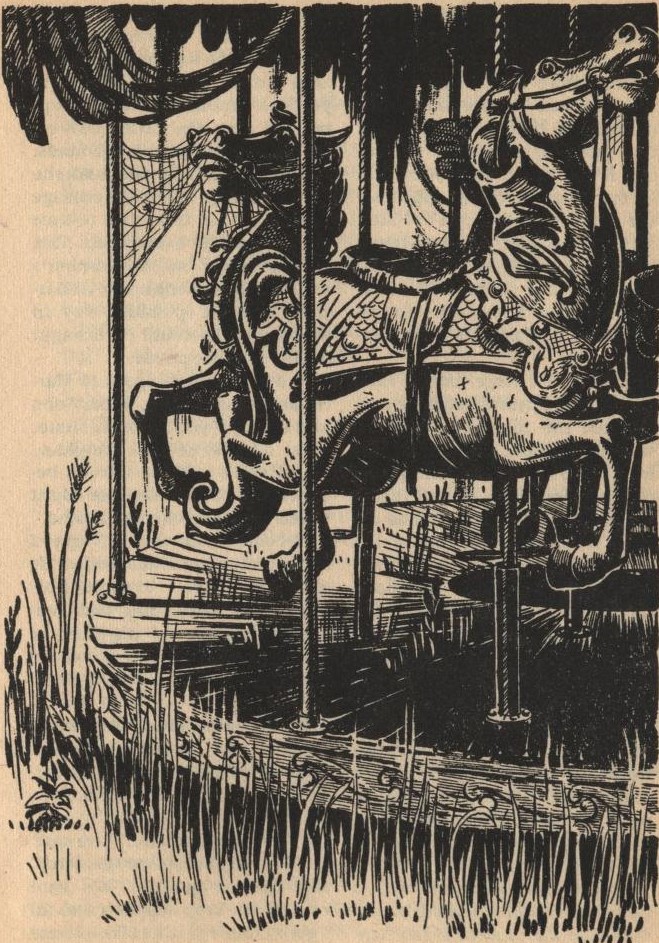

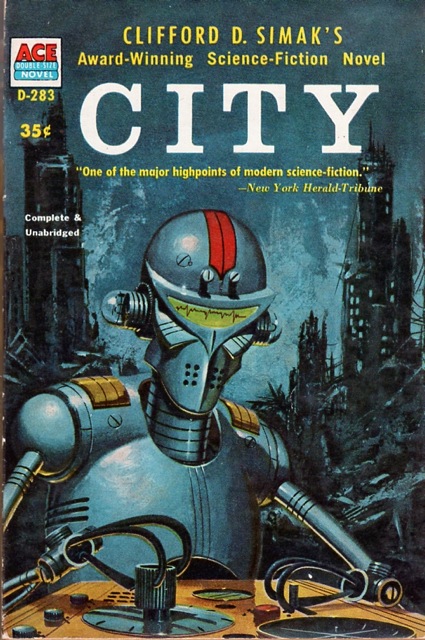

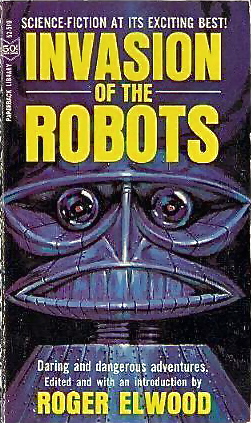

Once again, we're in the very far future, after human society has disappeared. The world is inhabited by robots. After an extremely long struggle, they have finally produced the ultimate being.

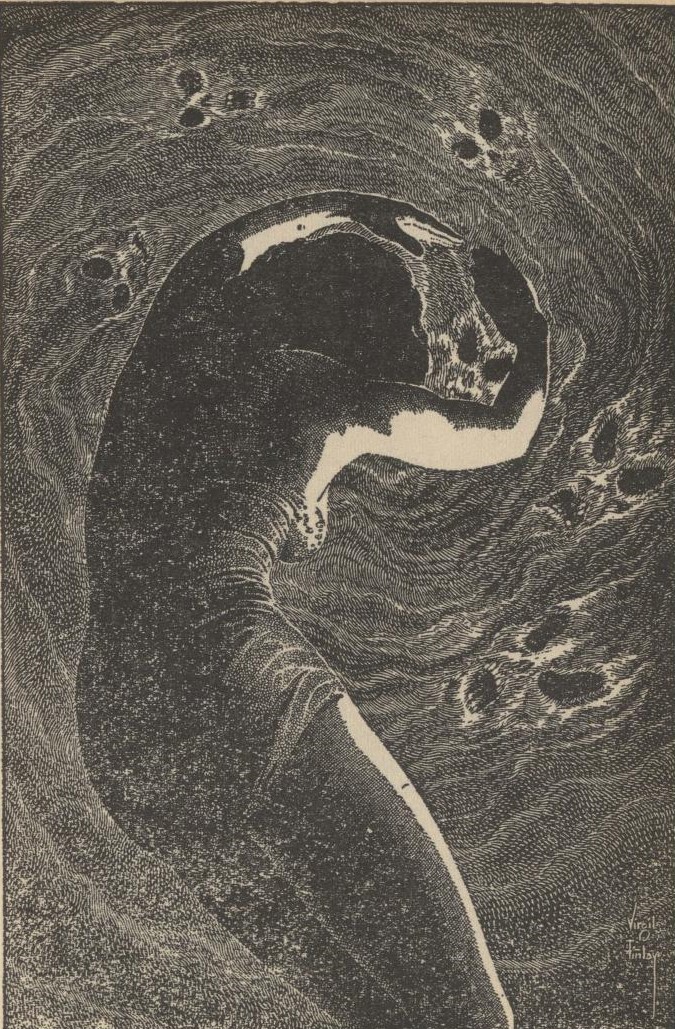

Well, just a glance at the illustration gives away the story's twist ending. Despite that, it's fairly effective. A minor piece that nevertheless accomplishes what it sets out to do.

Three stars.

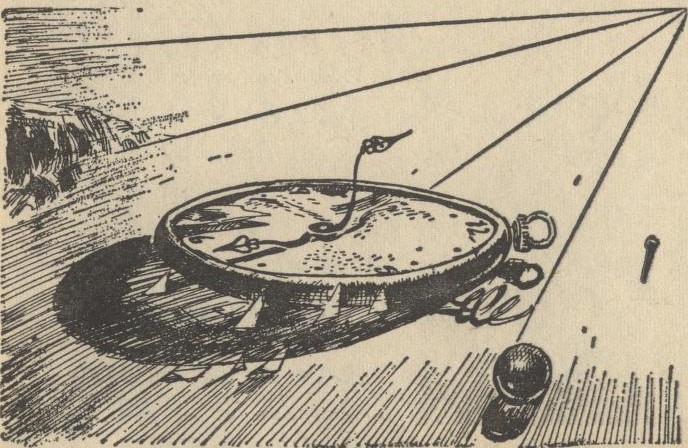

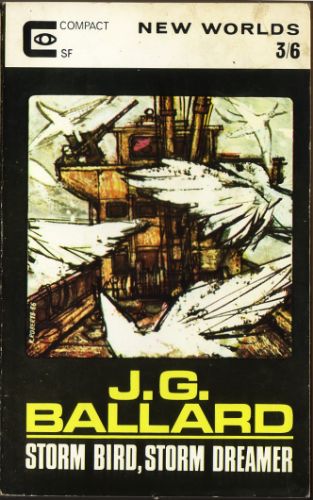

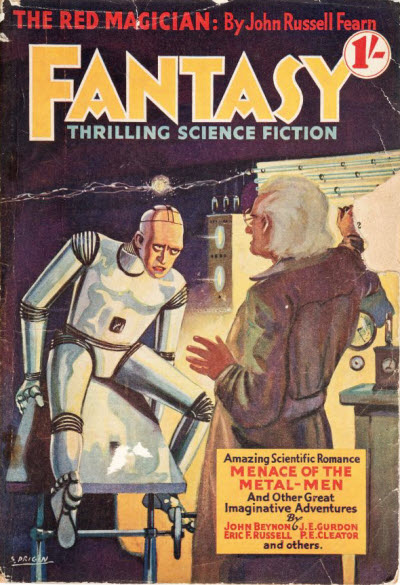

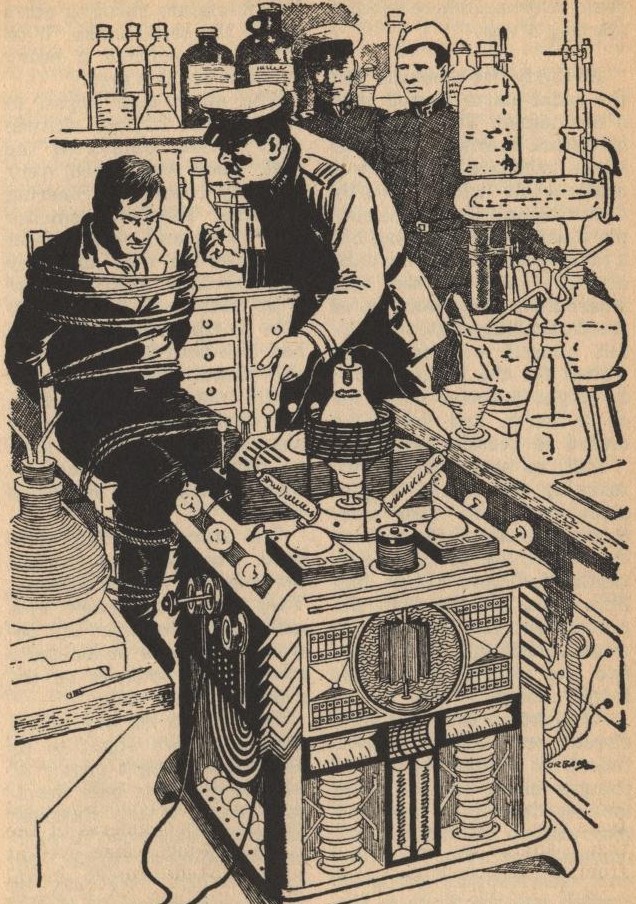

The Metal Doom (Part 1 of 2), by David H. Keller, M. D.

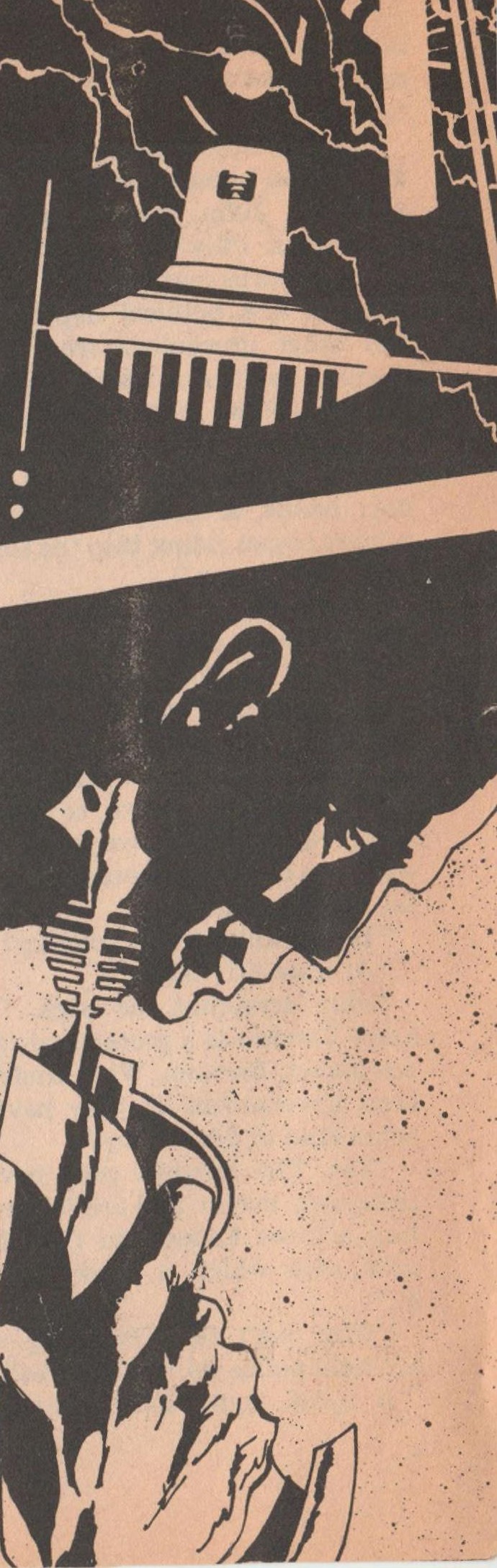

Illustration by Leo Morey.

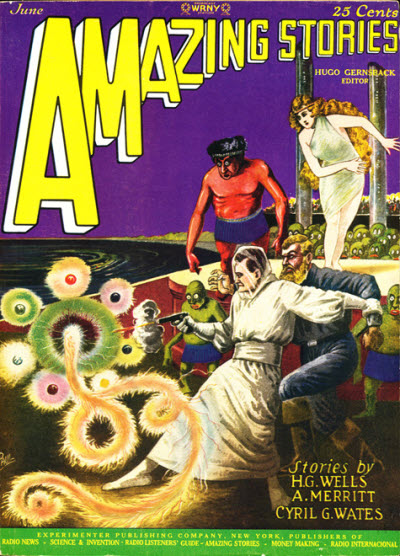

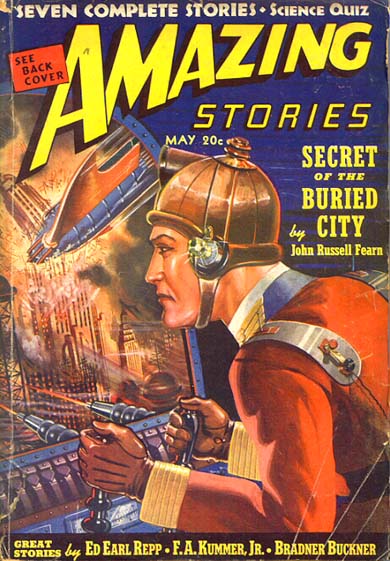

This Kelleryarn (Kellernovel?) originally appeared in three parts in the May, June, and July 1932 issues of Amazing Stories. All cover art also by Leo Morey.

Another physician in the issue.

This time there's a Ph.D. included.

Keller gets his name on all three covers.

For no apparent reason, all metal rots away. Naturally, this wipes out civilization. A husband and wife, with their infant daughter, escape the city early enough to find an abandoned farmhouse where they can live off the land.

A wealthy fellow not too far away sets up a group of folks who work together in order to fight off the bands of desperate criminals roaming around, now that no prison can hold them. After some violent battles, the first attempts to form some kind of loose confederation with other communities for mutual defense begin.

This is a grim story, not always pleasant to read. The main character changes from an ordinary citizen into somebody willing to kill dangerous people in cold blood. There's a disturbing subplot about the physician in charge of an institution for the so-called feebleminded, who has to make a terrible decision about what to do about them.

Three stars.

Order Out Of Chaos?

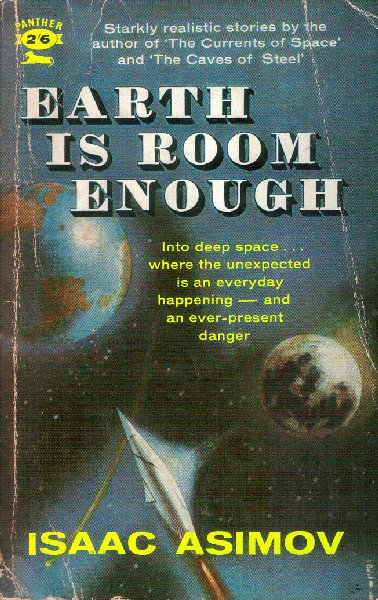

This wasn't a very good issue, with only the Sturgeon worthy of notice. I wonder if the magazine and its sister publication Amazing are going to slowly wear away into nothing, given the way they're both raiding back issues for the dregs. Maybe it's about time to look around for some better reading, like a classic novel.

From 1958, a groundbreaking work of modern African literature.

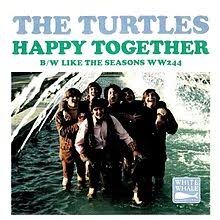

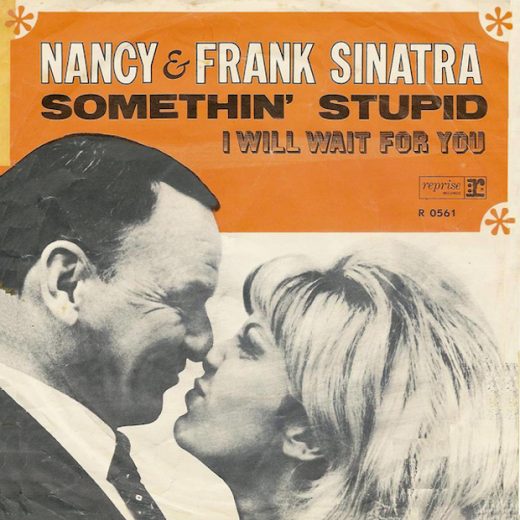

Or you could turn on the radio instead, and listen to KGJ for all the hits, all the time!

![[October 8, 1967] Things Fall Apart (November 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Fantastic_v17n02_1967-11_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

![[June 10, 1967] Music To Read By (July 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fantastic_196707-2-1.jpg)

![[April 16, 1967] The Generation Gap (May 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Fantastic_v16n05_1967-05_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[February 12, 1967] All's Fair in Love and War (March 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Fantastic_v16n04_1967-03_LennyS-cape1736_0000-2-672x324.jpg)

![[August 10, 1966] Dollars and Cents (September 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/FANTSEP1966-3.jpg)

![[June 10, 1966] Summer Reruns (July 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/fantastic_196607-2.jpg)

![[February 12, 1966] Past? Imperfect. Future? Tense. (March 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Fantastic_v15n04_1966-03_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

![[October 22, 1965] Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow (November 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Fantastic_v15n02_1965-11_Lenny_Silv3r_0000-2-672x247.jpg)

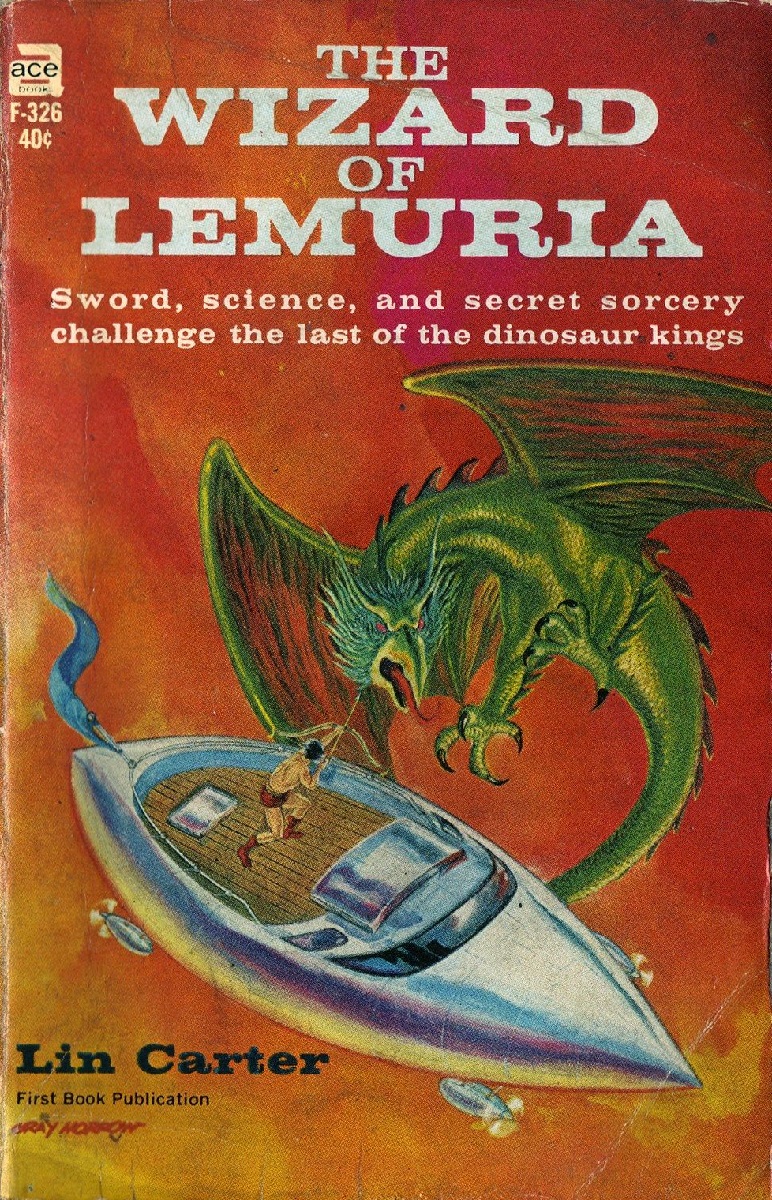

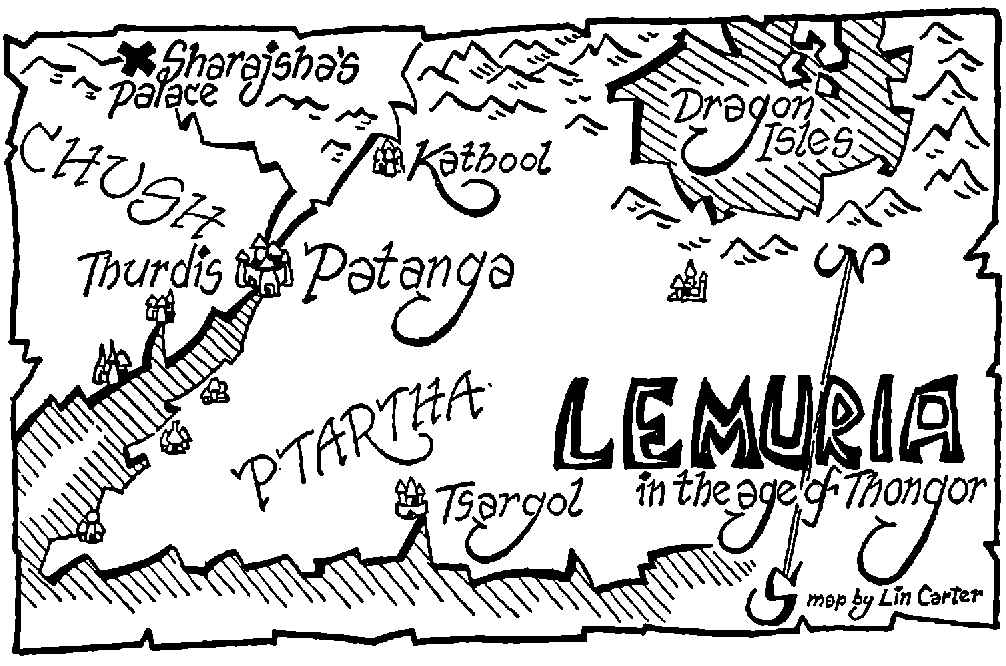

![[September 10, 1965] So Many Thews (Lin Carter's <em>The Wizard of Lemuria</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Cover-Wizard-of-Lemuria-672x372.jpg)

width="150"/>

width="150"/>

![[August 10, 1965] Binary Arithmetic (September 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Fantastic_v15n01_1965-09_0000-2-672x372.jpg)