by Gideon Marcus

Split Personality

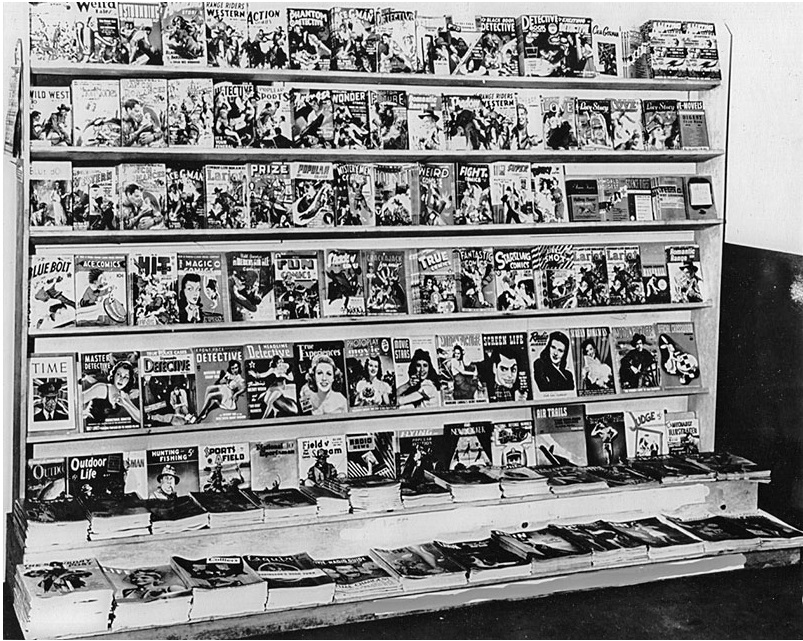

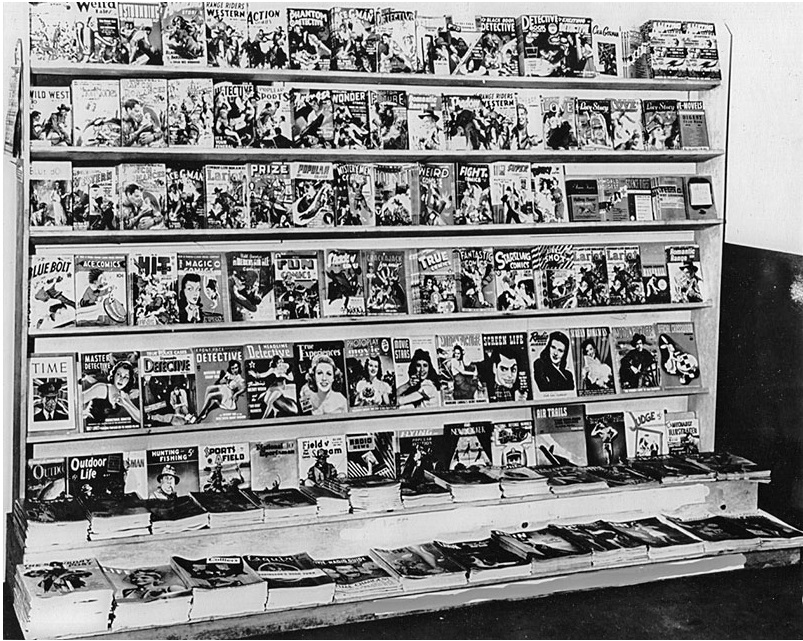

There's an interesting piece by Ted White in May's Science Fiction Review. He talks about how the magazines are on a slow, inexorable decline due to a number of factors. The biggest is that SF mags used to be just one subgenre of the myriad pulps, all of which had their lurid covers prominently displayed at every corner newsstand. Sure, the SF pulps weren't exactly of a piece with their mystery, Western, and thriller brethren, but Joe Palooka didn't care, grabbing the most attractive issues. So, SF thrived, making a profit even if it sold just 25% of a print run.

Note Astounding (now Analog) in the upper left and Amazing in the upper right

Then the pulps died in the 50s, partly due to changing tastes, mostly due to the collapse of American News Company, the main distributor for monthly mags (and comics). The remaining SF mags were consigned to lesser shelves, all by themselves. The average schmo got his entertainment from TV.

The profit mark has now risen to 50%–in other words, at least half of the issues printed must sell for the run to break even. This makes it very risky for the mags to try to expand their market by printing more issues. If they, say, print 50K and sell 35K, well and good. But if they then print 200K and sell 96K…they've lost money on the run.

Add to that even SF people are losing interest in mags, lured by paperbacks and the new paperback anthologies, and dismayed (as I have been) by the declining quality of stories over the last ten years. The only thing that keeps us subscribing is inertia and brand loyalty. That'll wear off unless the magazines manage to turn the ship.

The magazines have been around for almost half a century. Assuming they are around in the 21st Century, and if this trend continues, they will service an increasingly small fraction of the SF-interested community. They will be like the horseshoe crab: living fossils, unchanged for 300 million years, clinging to life in a wildly different environment.

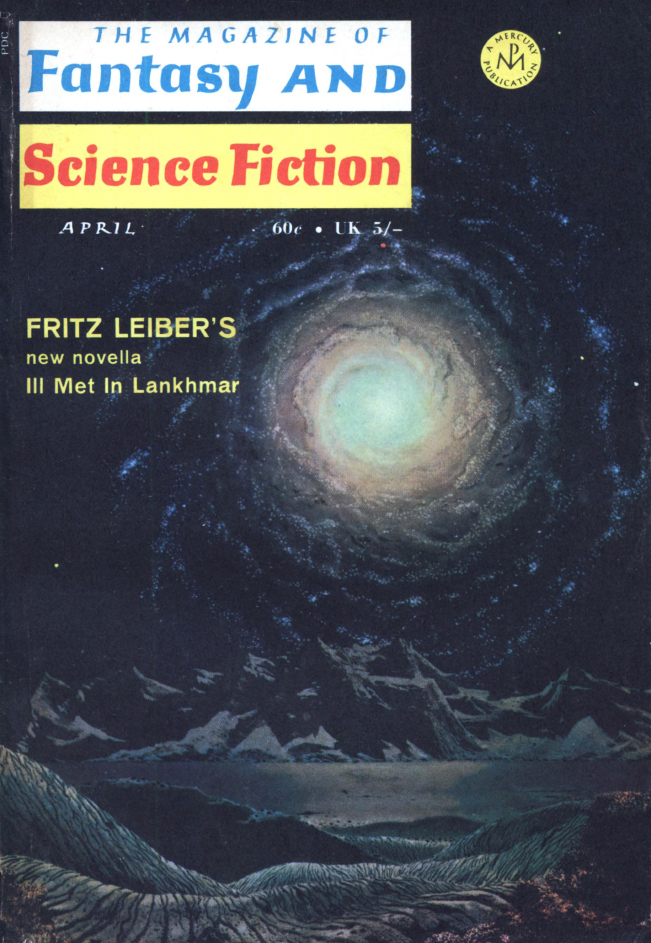

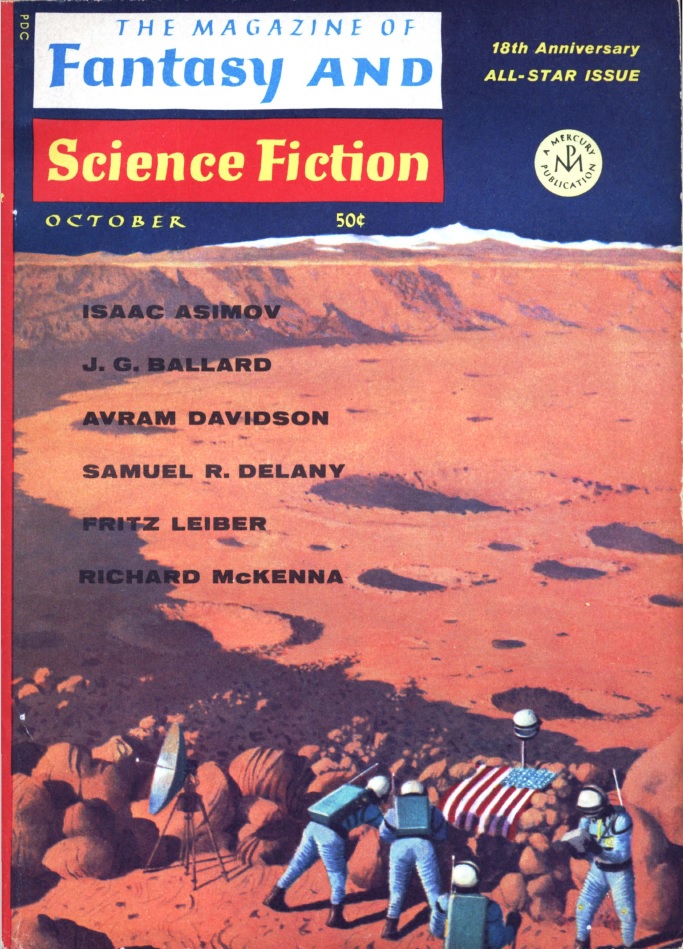

But that's all speculation. For now, enough good stuff still comes out in the mags to keep me buying. Though the high variability of the latest issue of F&SF may cause me to revisit that policy…

Over Hill and Dale

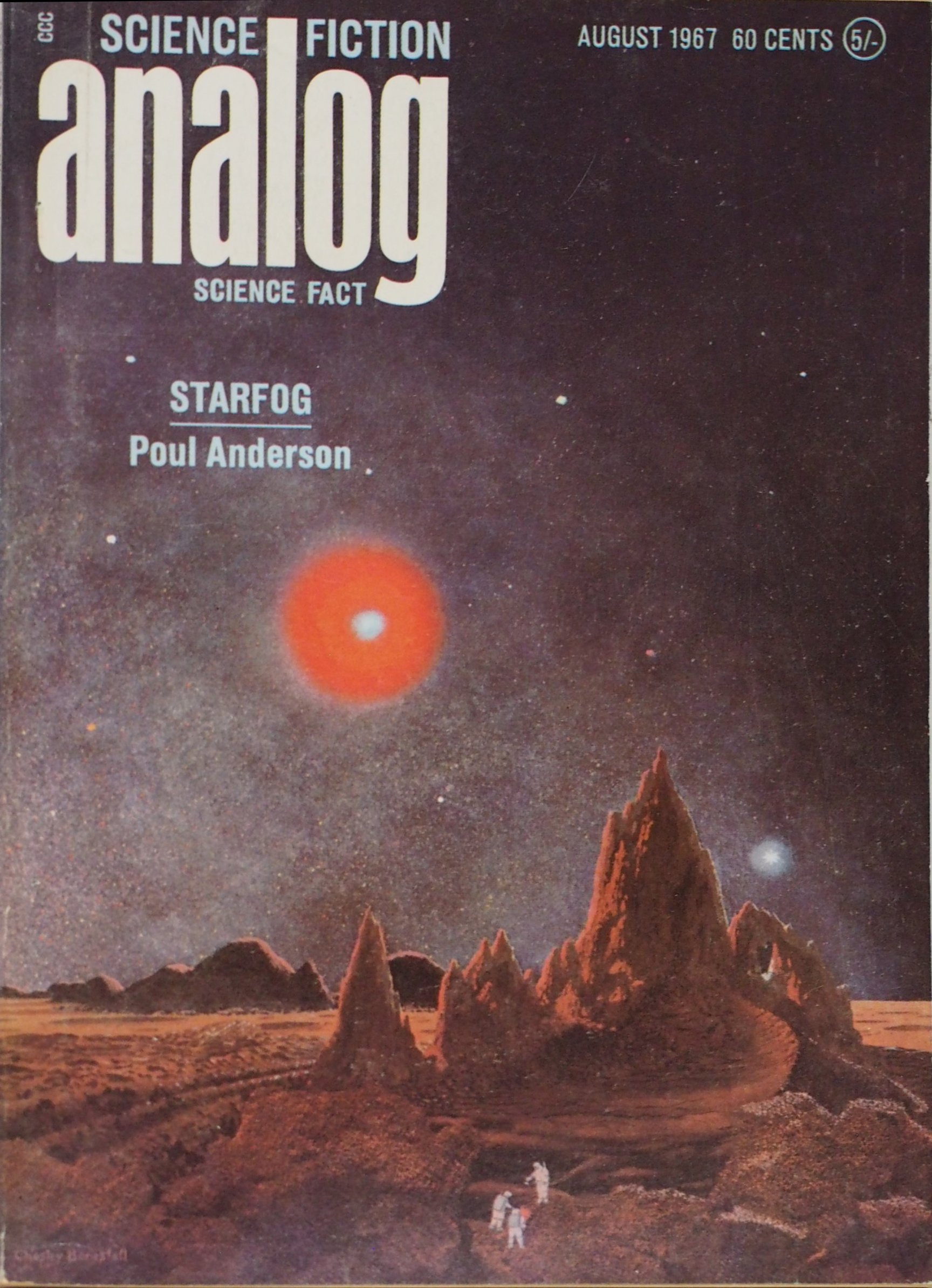

by Chesley Bonestell—this is the same nebula featured repeatedly in the Star Trek episode "The Alternative Factor"

Ogre!, by Ed Jesby

It's been four years since Ed Jesby offered up his first tale, Sea Wrack, which was so-so. His sophomore tale, Ogre!, is an improvement.

Knut the Ogre takes a nap sometime in the Middle Ages. When he awakes, covered in loam and with mushrooms growing in his ears, he finds he has slept clear through to the 20th Century. There (then), the seven-foot beast befriends a timid bookie on the run from the Mob. You see, Ogres are actually misunderstood creatures, quite nice and mild despite the calumny heaped upon them by humans.

Together, Knut and the bookie (and the bookie's seamstress pal) hatch a scheme to get the bookie off the hook and out of the business. And of course, it involves horses:

To Harry the plan seemed to be basically sound: after all the way to make money was on the races; there was no better way. You took bets or you made them, all other ways of earning a living were mysterious, square, or the result of inheritance.

It's really a charming tale, and it put me in a charitable mood for the rest of the issue. More fool me…

Four stars.

Butterfly Was 15, by Gilbert Thomas

A scurrilous German scientist has learned how to manipulate others with the judicious use of electrodes and remote transmitters. He meets his match when he locks horns with a traditional psychologist with methods of his own.

This is supposed to be a funny piece. I found its themes of mind control and Ephebophilia to be thoroughly repellent.

One star.

Sos the Rope (Part 3 of 3), by Piers Anthony

Once again, we turn to our friend, Brian, who will likely never volunteer for anything ever again…

by Brian Collins

We now find ourselves in the final installment of the latest F&SF serial, but unfortunately it’s so long as to encompass nearly half the novel. We run into trouble before we’ve even jumped into the story proper, as the recap section commits the grievous sin of telling us about things that we have not been able to read for ourselves. At the end of the previous installment you may recall that Sos and Sol are about to fight in the battle circle to see who takes custody of Sola and Soli, Sol’s wife and adopted daughter respectively. Apparently, between installments, Sos lost the fight, and is now journeying up “the mountain” to commit ritual suicide.

I do not understand how this happened. It could be that Anthony had turned in an early draft of the novel and had intended to write the fight scene between Sos and Sol, but all the same, this is such a glaring oversight as to show incompetence. I was confused at first because I thought I had somehow missed the ending of the previous installment, but no, I had not missed anything; it’s just that the fight and its immediate aftermath were kept “offscreen.”

Now up to date, we find Sos who, naturally, does not die on his way up this freezing mountain, but falls unconscious and is rescued by a small society of people who are somewhere between the crazies (the civilized people) and the nomads who roam the wasteland. We come across the second major female character of the novel (foreboding music plays), who, as you would expect, goes unnamed at first. She’s a short athletic girl whom Anthony repeatedly calls childlike and “Elfen,” but also attractive, which makes me wonder if Anthony might be appealing to a certain subspecies of male reader here. The girl steals Sos’s bracelet and makes him work for it, all but forcing him into taking her as his wife. As if the institution of marriage were not already filled with holes, the system presented in this novel may be fit for ants, spiders, and other small invertebrates, but not actual humans.

Since this is at least theoretically the last stretch of the narrative, in which we find our hero at his lowest point before he rises from the darkness, I need not go into great detail as to what happens next—except for one thing: Sosa (for that is her name now) reveals that she’s been desperate to find a husband, having gone through several men already, because she feels great angst at not being able to produce a child. Infertility is often sad news, to be sure, but in a world where contraception is presumably hard to acquire, I can’t imagine this strikes Sos’s ears as too sad; after all, he’s still committed to Sola in his heart.

Piers Anthony seems to understand women about as much as I understand the inner workings of a submarine.

Having given up his rope in his fight with Sol (another major detail we are not told about until after the fact), Sos has not only regained his confidence but taken up fists as his new weapon. I don't recall if we get his new full name (as men in the novel’s world have a monosyllable followed by their weapon of choice), but Sos the Fist sounds…….

Anyway, there is an inevitable rematch, and this time Sos is victorious. The ending here implies that there may be a sequel in the works, but I’m not waiting to see what Anthony does next. 1 out of 5 stars for this installment, and barely 2 out of 5 stars for the novel.

by Gideon Marcus

Faunas, by L. Sprague de Camp

Someone in the zines was complaining that magazines never run worthy poetry anymore, that back in the golden days of the 50s, most of the pieces were memorable.

Keeping up the trend, De Camp offers up a snatch of doggerel comparing the titanic beasts of yore with the primate beasts of now. Pretty pat stuff.

Two stars.

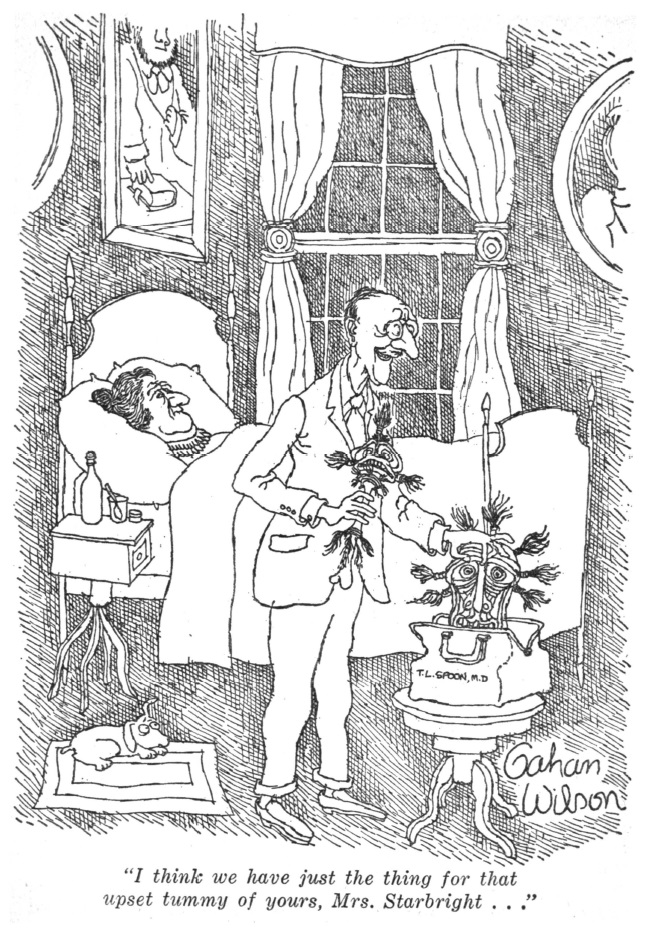

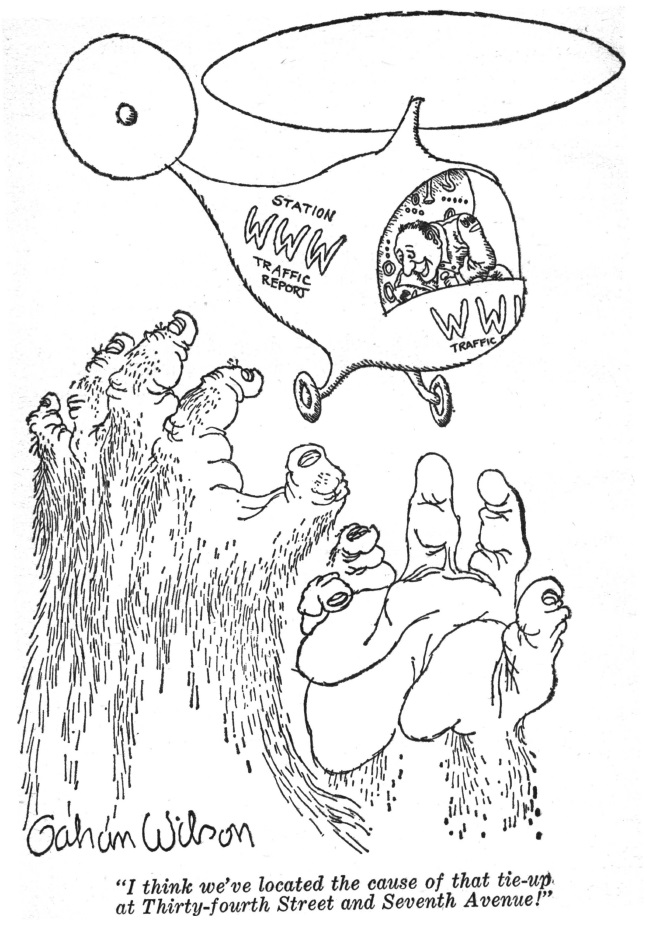

Harry's Golden Years, by Gahan Wilson

It is amazing the lengths to which people will go to maintain a sinecure. Harry Van Deventer is the richest man in the world, senile and filled with infantile rage and a teen's hormones. His hangers-on can only manage him by keeping his surroundings perfectly controlled—a willing nurse here, an emergency surgery to fix a day's incaution there. But even a 24/7 watch can slip up…

It's hard to imagine a man both so utterly terrible and yet so rich and powerful that so many would endure so much to keep him alive. But I suppose venality trumps all.

Three stars.

The Evaporation of Jugby, by Stephen Barr

Wadsworth Jugby is a big zero, a department store Vice President-without-portfolio, mediocre in every way. He finally gets the opportunity to live life from a different perspective when his friend, Dan Byron, invents a psyche-swapping machine. Intoxicated by his exchange, he eagerly agrees to expand the scope of the experiment, round-robining with six other folks. The end is…well, given away by the title.

Fluff, with one funny line:

"Jugby could suggest a puzzled frown without lowering his eyebrows-some monkeys can do this."

Two stars.

The Dying Lizards, by Isaac Asimov

Last month, the Good Doctor had a terrific article on the dinosaurs. This month, unfortunately, he indulges in speculation, which never works out well.

The topic this time 'round is the sudden death of the dinosaurs. He advances various climatic and medical hypotheses, discarding each one in turn. He poopoos the idea of mammals being "superior" as we existed alongside dinosaurs for most, if not all, of their tenure on Earth. Asimov leaves off with the suggestion that an external event caused it, specifically a nearby supernova that spiked radiation-induced mutations.

Again, I have trouble seeing how the dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and icthyosaurs and pleisiosaurs could all have destructive mutations but not the birds and mammals. I think Ike's cute idea that dinosaurs evolved intelligence and killed themselves with powerful weapons, which would have occurred in the blink of an paleontological eye and thus escape excavation, is more plausible.

Three stars.

A Scare in Time, by David R. Bunch

The demarkations of time, the seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, and centuries, have met in their onion dome. Tired of being measured and metered by humanity, they plot their ultimate revenge…only to have it foiled by human ingenuity.

A cute modern fairy tale. Three stars.

The Moving Finger Types, by Henry Slesar

Twilight Zone department: Legget couldn't figure out what was wrong with his life. It was like his every move was laid down in a script, and he'd lost the page. Little did he know, that's exactly what had happened.

A fun bit on predestination told in Slesar's competent screenwriter fashon.

Four stars.

by Gahan Wilson

Mixed feelings

You can see my problem. If you read from either end of this issue, you've got a good 30 pages of material (and you can count Merril's book column, too, though I rarely agree with her assessments, and her tastes are drifting far afield of SF these days). But if you read through the middle, that's a lot of one-star territory to slog through. A lot.

Is half a loaf better than none? More importantly, is it worth fifty cents a month?

Only you can decide…

</small

</small

![[March 20, 1970] Here comes the sun (April 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700320fsfcover-651x372.jpg)

![[September 22, 1969] Unsmoothed curves (October 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/690922fsfcover-658x372.jpg)

![[August 24, 1969] Flying and dragging (September 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/690820fsfcover-409x372.jpg)

![[August 20, 1968] A tale of two issues (September 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/680820cover-659x372.jpg)

![[April 30, 1968] (Partial) success stories (May 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/680430cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 18, 1967] Skål! (October 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/670918cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 31, 1967] Canceling waves (August 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670731cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 20, 1967] Sag in the middle (February <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670120cover-1-422x372.jpg)

![[December 31, 1966] Barriers to quality (January 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661231cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 16, 1966] Calm Spots (July 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660616cover-672x372.jpg)