by Victoria Silverwolf

High Velocity

Vehicles travelling very rapidly were in the news this month, both in a good way and in a bad way.

On March 2, the French/British supersonic airplane Concorde made its first test flight in Toulouse, France. At the controls was test pilot

André Édouard Turcat.

Up, up, and away!

The plane reached a speed of 225 miles per hour (far below the speed of sound) and stayed in the air for twenty-seven minutes. Just a test, but expect a lot of sonic booms in the near future.

The same day, tragedy struck the Yellow River drag racing strip in Covington, Georgia. Racer Huston Platt was at the wheel of a car nicknamed Dixie Twister when it smashed through a chain link fence and hurdled into the crowd at 180 miles per hour.

Image of the disaster from a home movie taken by a spectator.

Eleven people were killed instantly. One later died in the hospital. More than forty were injured.

All this rushing around is likely to induce vertigo. Appropriately, the Number One song in the USA this month is Dizzy by Tommy Roe, a catchy little number that captures the feeling perfectly.

Even the cover art makes my head spin.

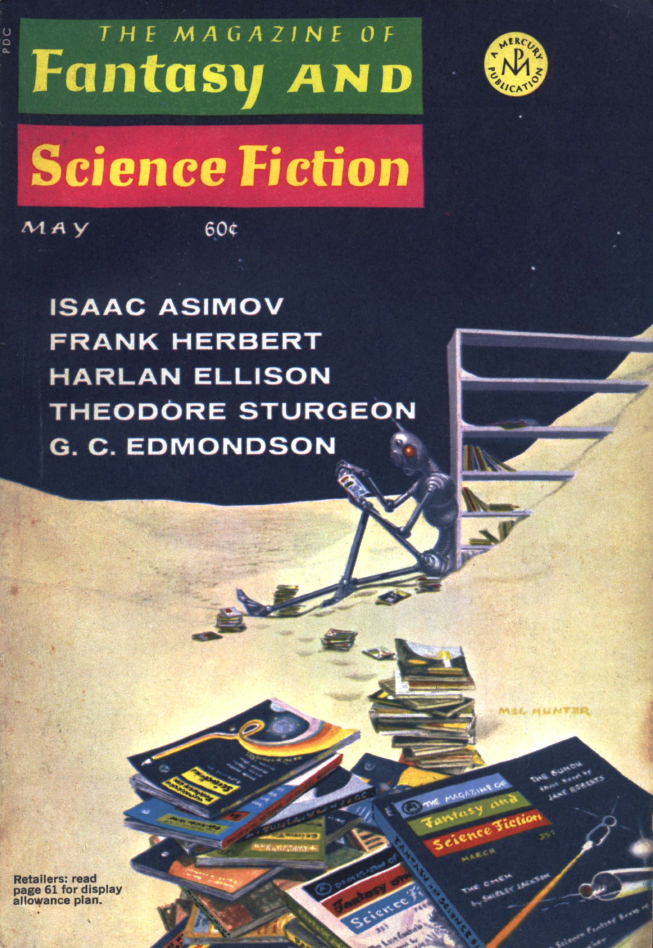

Speed Reading

With no less than thirteen stories in the latest issue of Fantastic, it's obvious that several of them are going to be quite short, resulting in quick reading.

The new stories slightly outnumber the reprints, at seven to six, but the old stuff takes up more than twice as many pages. Apparently today's writers like to finish their works at a quicker pace than their predecessors. Or maybe it's just a lot cheaper to buy tiny new works and fill up the rest of the magazine with longer reprints.

Cover art by Johnny Bruck.

As usual, the cover is also a reprint. It appeared on the German magazine Perry Rhodan a few years ago.

Also as usual, the original looks better.

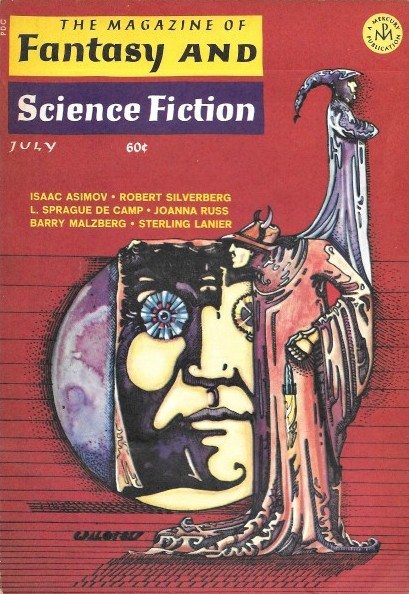

Characterization in Science Fiction, by Robert Silverberg

This brief essay by the Associate Editor promotes more depth of character in the genre, and praises new authors Roger Zelazny, Samuel Delany, and Thomas Disch for their skill in that area of writing. Can't argue with that.

No rating.

In a Saucer Down for B-Day, by David R. Bunch

Illustration by Dan Adkins.

The magazine's most controversial writer returns with a tale that is closer to traditional science fiction than most of his works. The narrator is an Earthman who is returning to his home planet with an alien. He wants to show the extraterrestrial Earth's big annual celebration.

The author makes a point about a current social problem, maybe a little too obviously. Even if this had been published anonymously, it would be easy to tell it's by Bunch from the style. (Just the fact that the narrator says YES! more than once is a strong clue.) More readable than other stuff from his pen.

Three stars.

The Dodgers, by Arthur Sellings

A sad introduction tells us the author died last September. This posthumous work features an engineer and a physician who land on a planet where many of the alien inhabitants are suffering from weakness and green blotches on their skin. As soon as the humans arrive, a bag full of gifts for the extraterrestrials vanishes. The mystery involves an unusual ability of the aliens.

I hate to speak ill of the dead, but this isn't a very good story. The premise strains credibility, to say the least, and the ending is rushed.

Two stars.

The Monster, by John Sladek

Illustration by Bruce Eliot Jones

A fellow eager to be a space explorer replaces a guy who's been the only person on a distant planet for a long time. The world turns out to be a dreary, boring place. The environment is so bad that our protagonist can't go outside for more than a moment. His only company is a robot in the form of a woman.

The author makes his point clearly enough. You're likely to see it coming a mile away. Still, it's not a bad little yarn.

Three stars.

Visit, by Leon E. Stover

The Science Editor for Fantastic and Amazing (which must be an easy job; do they ever have any science articles?) gives us this account of aliens landing in Japan. The American military officers present consult with a science fiction writer and a cultural anthropologist. After a lot of discussion, the aliens finally come out of their spaceship.

For a story in which not much happens this sure goes on for a while. Much of the text consists of references to other SF stories. The ending is anticlimactic. It left me thinking So what?

Two stars.

Ascension, by K. M. O'Donnell

The introduction reveals that O'Donnell is a pseudonym for the editor.

But which editor?

Glancing at the table of contents, you see that the Editor and Publisher is Sol Cohen, and the Managing Editor is Ted White. Cohen or White?

Trick question! It's actually Barry N. Malzberg, who was very briefly editor for Fantastic and Amazing. (My esteemed colleague John Boston goes into detail about the situation in his article about the March issue of Amazing.)

Obviously this issue was assembled under the auspices of Malzberg. Nobody ever said the publishing industry was fast.

Anyway, this is a New Wave yarn about a future President of the United States. (The 46th, which I guess puts the story somewhere around the year 2024 or so.) Civil liberties are thrown out, the President has an advisor killed, he gets kicked out by the opposition and shot, the cycle goes on. Something like that.

You can tell it's New Wave (with an acknowledged nod to J. G. Ballard) because sections of the text are in ALL CAPITALS and it ends in the middle of a sentence. I suppose it's some kind of commentary on American politics.

Two stars.

The Brain Surgeon, by Robin Schaefer

Guess what? This is yet another pseudonym for Malzberg. Must have had trouble filling up the issue. (No surprise, given the miserly budget.)

A man sends away for a home brain surgery kit that he saw advertised on a matchbook cover. He gets the instruments and an explanatory pamphlet in the mail. But what can he do with it?

Something about this brief bit of weirdness appealed to me more than it should. There's not much to it, really, but what there is tickled my fancy.

Three stars.

How Now Purple Cow, by Bill Pronzini

A farmer sees a (you guessed it) purple cow in his field. There's some talk of UFOs in the area. Then there's a twist at the end.

Very short, without much point to it. A shaggy dog (cow?) story. A joke without a punchline.

One star.

On to the reprints!

The Book of Worlds, by Dr. Miles J. Breuer

Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear with this pre-Campbellian work of scientifiction from the pages of the July 1929 issue of Amazing Stories.

Cover art by Hugh Mackay.

A scientist discovers a way to view the fourth dimension. This allows him to see a enormous number of worlds similar to our own Earth, at stages of development from the first stirrings of life to the future of humanity. What he perceives has a profound effect on him.

Illustration by Frank R. Paul.

I have to confess that I wasn't expecting very much out of a story from the very early days of modern science fiction. This was a pleasant surprise. The author clearly has a point to make, and makes it powerfully. What happens to the scientist at the end may strike you as either poignant or silly. Take your pick.

Three stars.

The Will, by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

The January/February 1954 issue of the magazine supplies this moving tale.

Cover art by Vernon Kramer.

The narrator's teenage foster son is dying of leukemia. The boy is obsessed with a television program about a time travelling hero called Captain Chronos.

(No doubt this was inspired by the author's work on the TV show Captain Video not long before the story was first published.)

Illustration by Jay Landau.

The boy has a plan, involving his collection of stamps and autographs. But does he have enough time left?

Just from this brief description, you probably already have a pretty good idea of what's going to happen. Despite the fact that the plot is a little predictable, however. this is a fine story. The emotion is genuine rather than sentimental. The ending is both joyful and sad.

Four stars.

Elementals of Jedar, by Geoff St. Reynard

Hiding behind that very British pseudonym is American writer Robert W. Krepps. This pulpy yarn comes from the May 1950 issue of Fantastic Adventures.

Cover art by H. J. Blumenfeld.

A spaceship captain with the manly name of Ken Ripper and his motley crew of aliens from various worlds are in big trouble. Forced to land on a planet said to be inhabited by living force fields of pure malevolence, they have to figure out a way to escape with their lives.

Illustration by Rod Ruth.

Boy, this is really corny stuff. I have to wonder if it's a parody of old-time space opera. When the hero curses by saying Jove and bounding jackrabbits!, it makes me think the author is pulling my leg. The fact that one of the aliens on the spaceship is a humanoid twelve inches tall makes me giggle, too. Even if it's tongue-in-cheek, a little of this goes a long way.

Two stars.

The Naked People, by Winston Marks

This story comes from the September 1954 issue of Amazing Stories.

Cover art by Ralph Castenir.

The combination of a sore ear and a fight in a tavern sends the narrator to the hospital with a brain infection. When he comes out of his coma, he is able to see the ethereal figure of a unclothed man. The lecherous fellow is able to solidify himself sufficiently to have his way with a pretty nurse while she's unconscious and under his control.

Illustration uncredited.

Then a female ghostly being shows up, with an obvious interest in our hero. It seems that these folks have been hanging around, unperceived by normal people, since the dawn of humanity. They materialize enough to steal food and, to put it delicately, act as incubi and succubi.

I get the feeling that the author didn't quite know how to end the story. The hero fends off the advances of the lustful female being and saves the pretty nurse from the male one. He even marries her. But the naked people are still around, with all that implies.

An unsatisfying conclusion and a slightly distasteful premise make for a less than enjoyable reading experience.

Two stars.

And the Monsters Walk, by John Jakes

This two-fisted tale comes from the July 1952 issue of Fantastic Adventures.

Cover art by Walter Popp.

The narrator starts off aboard a ship bound for England from the Orient. Burning with curiosity, he investigates the secret cargo hold, although the captain warned the crew this was punishable by death. He finds boxes containing humanoid creatures.

Barely escaping with his life, he makes his way to shore. Mysterious figures are out to kill him. On the other hand, a Tibetan mystic and a beautiful young woman try to help him. In return, they want his aid in combating a conspiracy to destroy Western civilization by using demons to slaughter world leaders.

Illustration by David Stone.

John Jakes is best known around here for his tales of Brak the Barbarian. Those stories proved that he had studied the adventures of Conan carefully. This yarn convinces me that he is also very familiar with the pulp magazines of the 1930's.

I'll give him credit for not being boring, anyway. The action never stops, although you won't believe a minute of it. The author's intense, almost frenzied style keeps you reading.

Three stars.

I, Gardener by Allen Kim Lang

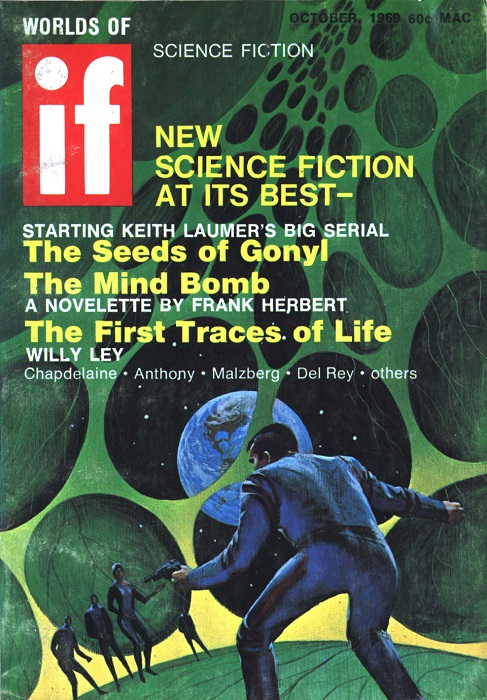

Our last story comes from the December 1959 issue of the magazine.

Cover art by Ed Valigursky.

The narrator pays a visit to a prolific writer. He speaks to a very strange gardener, who proves to be something other than what he seems.

I'll leave it at that, because I don't want to give away too much about the simple plot. You may be able to figure out who the model for the writer is, given the title of the story and the fact that the character's name is Doctor Axel Ozoneff. (The introduction to the story makes it obvious, so I'd advise not looking at it.)

Not a great story.

Two stars.

Fantasy Books, by Fritz Leiber and Alexei Panshin

Leiber looks at novels by E. R. Eddison, and Panshin has kind words to say about The Last Unicorn by Peter S. Beagle.

No rating.

Quickly Summing Up

Another average-to-poor issue, with only Miller's story rising above that level. At least most of the pieces make for fast reading, although a couple of the worst ones may make you furious at their lack of quality. You may be tempted to watch an old movie on TV instead.

From 1954, so it should show up on the Late, Late Show sometime soon.

![[June 24, 1970] In love with "Ishmael in Love" (July <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700624fsfcover-409x372.jpg)

![[April 20, 1970] Not the final quarry (May 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700420fsfcover-653x372.jpg)

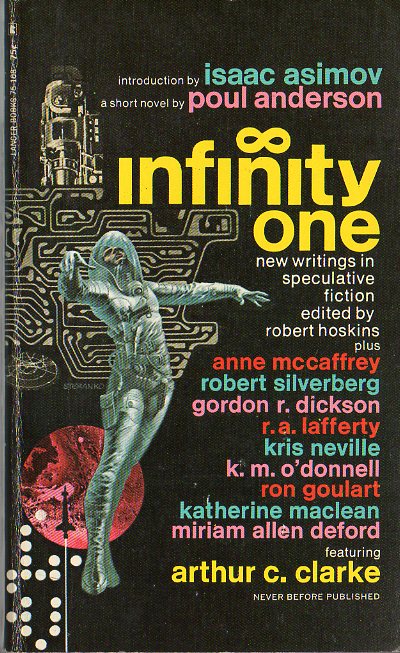

![[April 8, 1970] All Too Finite (<em>Infinity One</em>, edited by Robert Hoskins)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ANCL00221-400x372.jpg)

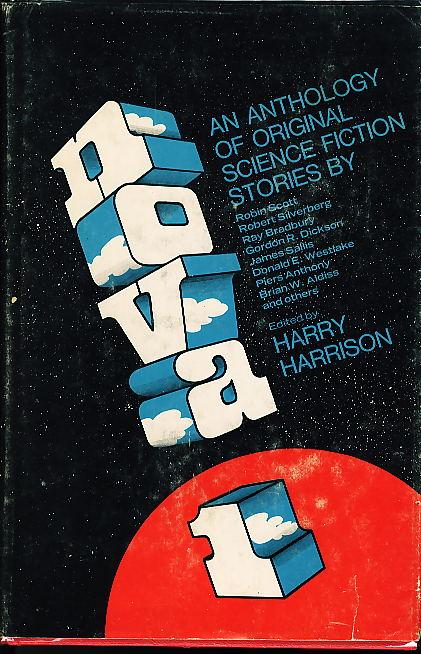

![[March 4, 1970] Harry's Heroes (<em>Nova 1</em>, edited by Harry Harrison)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/NVFCNDXTDF1970-421x372.jpg)

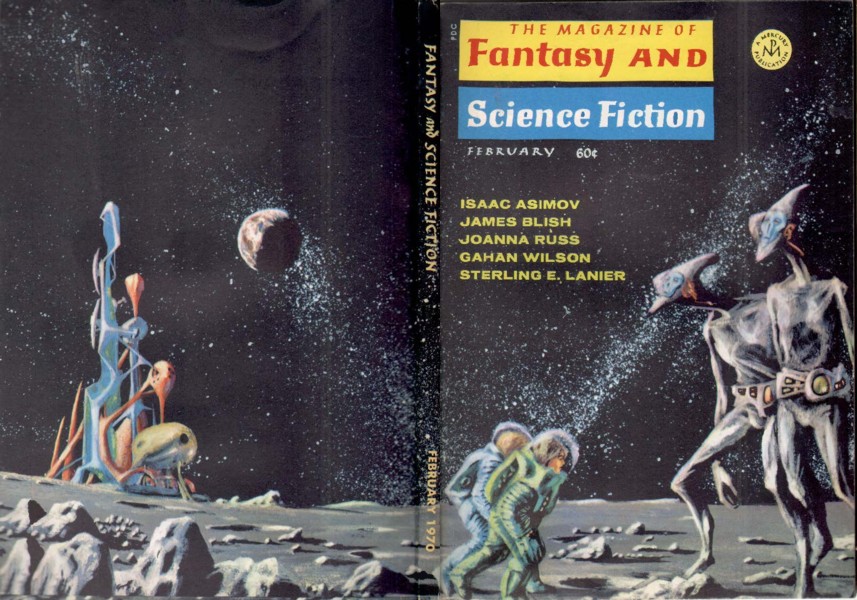

![[January 20, 1970] Jolly good Ffelowes (February 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700120fsfcover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 20, 1969] You say you want a revolution… (December 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/691120fsfcover-408x372.jpg)

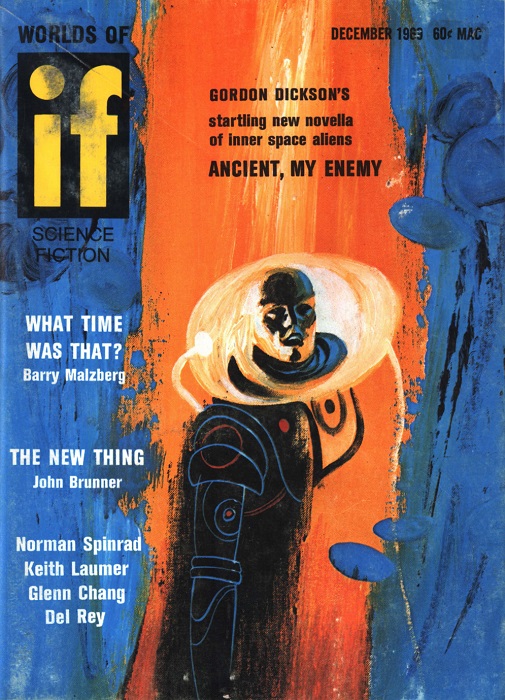

![[November 2, 1969] Love and Hate (December 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/IF-1969-12-Cover-505x372.jpg)

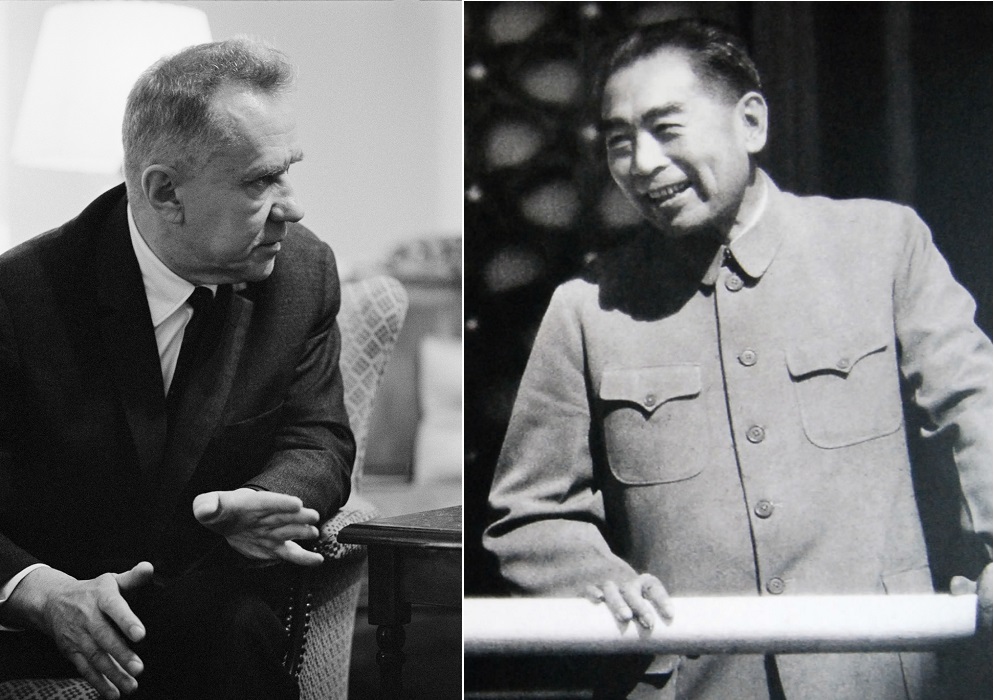

l. Soviet Foreign Minister Alexei Kosygin, r. Chinese Foreign Minister Chou Enlai

l. Soviet Foreign Minister Alexei Kosygin, r. Chinese Foreign Minister Chou Enlai Vaguely suggested by Ancient, My Enemy. Art by Gaughan

Vaguely suggested by Ancient, My Enemy. Art by Gaughan![[September 4, 1969] <i>Plus ça change</i> (October 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/IF-1969-10-Cover-487x372.jpg)

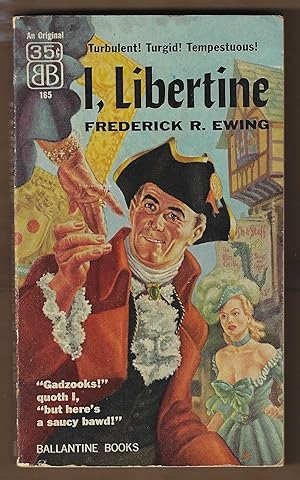

Penelope Ashe, in part, with the cover model superimposed.

Penelope Ashe, in part, with the cover model superimposed.

Supposedly for Seeds of Gonyl. If so, it’s from later in the novel. Art by Gaughan

Supposedly for Seeds of Gonyl. If so, it’s from later in the novel. Art by Gaughan![[April 12, 1969] A New Venture (May 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Venture-1969-05-Cover-494x372.jpg)

The first and last covers for the first run of Venture. Art in both by Ed Emshwiller

The first and last covers for the first run of Venture. Art in both by Ed Emshwiller This singularly unattractive cover is by Bert Tanner.

This singularly unattractive cover is by Bert Tanner.![[March 10, 1969] Speed (April 1969 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/COVERHALF-672x372.jpg)