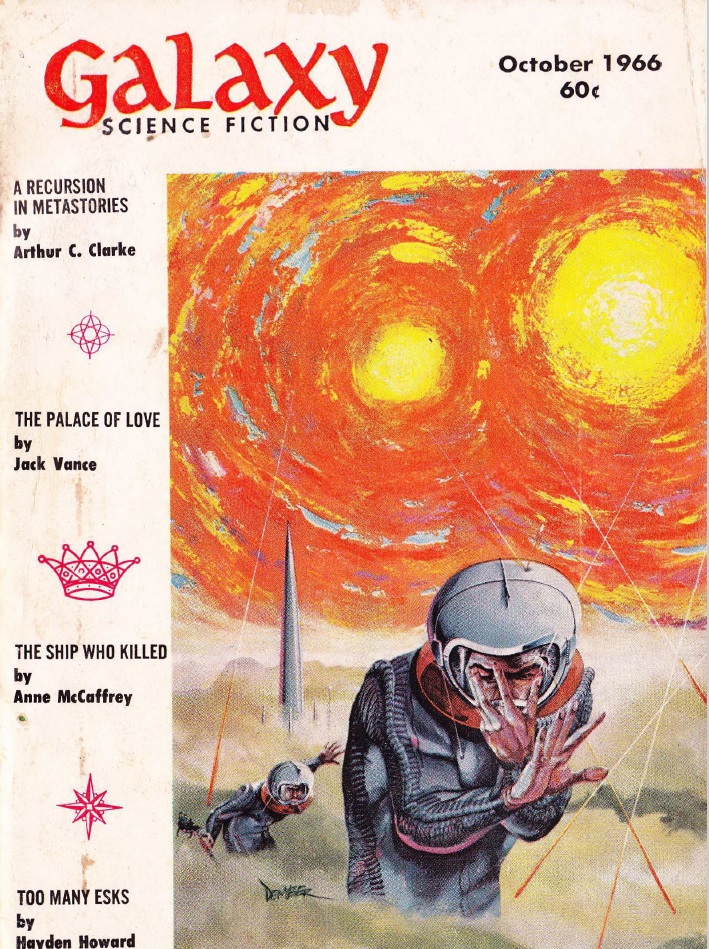

Big, But . . .

by John Boston

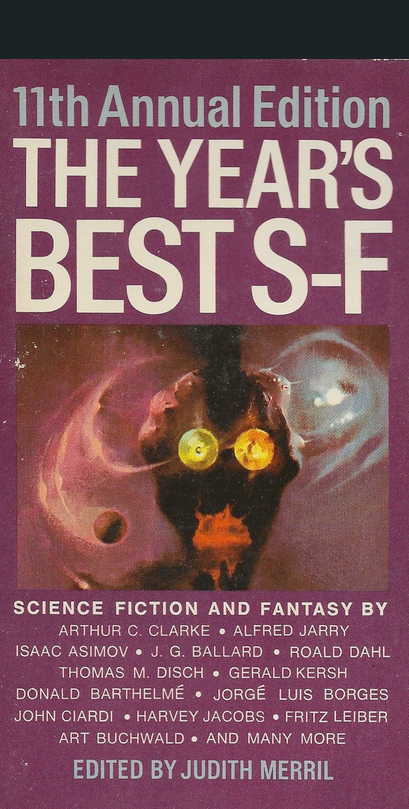

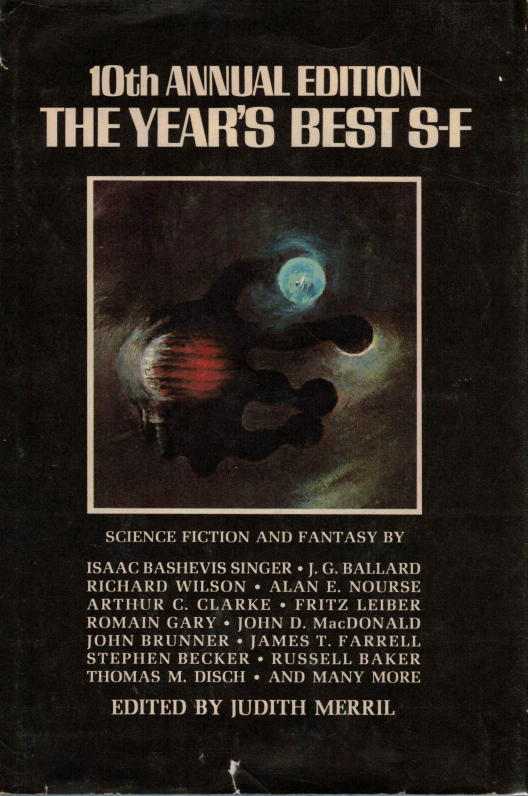

No matter if you don’t believe in Santa Claus. Judith Merril is back with another volume of her annual anthology, 11th Annual Edition the Year’s Best S-F (sic), from Delacorte Press just in time for the Christmas trade. If you missed the boat on Christmas, surely you can make it work for Valentine’s Day.

by Ziel

The overall package is familiar: 384 pages thick, a crowded contents page, a short introduction, but lots of running commentary between items, sometimes about the stories or authors and sometimes, it seems, about whatever crosses Merril’s mind as she assembles the book. There is the usual Summation at the end, but the extensive Honorable Mentions listing is gone, though she mentions some items that didn’t make the cut in the Summation and commentary.

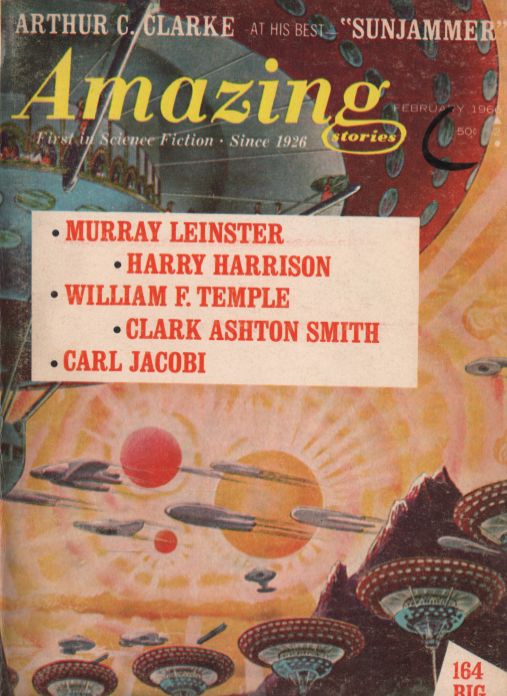

The contents are eclectic as usual, but let Merril tell it: “The stories and poems and essays here have been selected from as wide a range as I could cover of books and periodicals published here and in England last year. About half the entries are from the genre magazines. The rest are from books and from such diverse sources as Mademoiselle and Escapade, The Colorado Quarterly and the Washington Post, Playboy and the Saturday Review (and Ambit and King in England).” “Of the year” in the title is notional at best. This volume includes a story by Jorge Luis Borges, The Circular Ruins, which dates from 1940, and an . . . item . . . by Alfred Jarry, who died in 1907.

The usual disclaimer is here, too. From the Introduction:

“This is not a collection of science-fiction stories.

“It does have some science fiction in it—I think. (It gets a little more difficult each year to decide which ones are really science fiction—and frankly I don’t much try any more.)”

Unfortunately this year’s book falls short of most of its predecessors to my taste. Unusually, some of the selections by the biggest-name authors are strikingly lackluster. Isaac Asimov’s Eyes Do More than See, from F&SF, is a short piece of annoying pseudo-profundity about the down side of becoming a disembodied energy being. Gordon R. Dickson’s Warrior (from Analog), part of his militaristic Dorsai series, gives us a protagonist who is such a comprehensive superman that his enemies are rendered helpless by his mere presence, and the story turns quickly into self-parody. J.G. Ballard is represented by one very fine story, The Drowned Giant, from Playboy, and another, The Volcano Dances, which reads like a parody of his recurrent theme of humans happily pursuing self-destructive obsessions: his protagonist takes up residence near a volcano that’s about to blow, refuses all entreaties to leave, and at the end is apparently heading towards it as the volcano’s rumbling becomes more ominous.

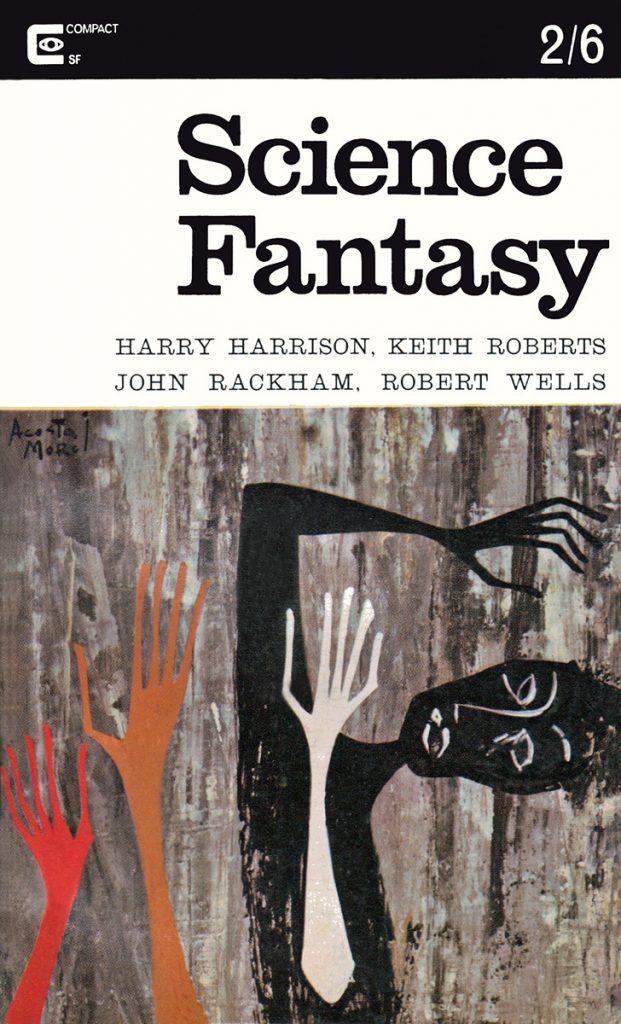

There is a decided swerve this year towards the British magazines New Worlds and Science Fantasy, with four stories from each here. The best of this lot is David I. Masson’s Traveler’s Rest (New Worlds), which depicts a world where the passage of time varies with latitude, much faster at the North Pole where a furious high-tech war is ongoing, and more slowly towards the equator where people live more or less normal lives. In some of the others, it is quite unclear what is going on, and purposefully: two of them are (or seem to be) narrated by mental patients (David Rome’s There’s a Starman in Ward 7 and Peter Redgrove’s long poem The Case (both from New Worlds)). Josephine Saxton’s The Wall (Science Fantasy) is a strange, haunting, allegorical-seeming story of lovers who never meet except through a small hole in a wall dividing a world that seems like some sort of artificial construct that they don’t understand and is unexplained to the reader.

As always, Merril has harvested some stories from non-genre sources, most sublimely Jorge Luis Borges’s The Circular Ruins, from 1940. It’s a metaphysical fantasy about a man who travels in a canoe to a ruined temple to carry out a mission: “He wanted to dream a man: he wanted to dream him with minute integrity and insert him into reality.” This story, resonantly translated from the Spanish, is the find of the book. Also noteworth is Game, by Donald Barthelme, from the New Yorker, about two guys locked in an underground bunker charged with dispatching nuclear missiles as ordered. They have gone months without relief and are pretty much nuts; it is strongly hinted that the war has happened and they’re never getting relieved. Gerald Kersh’s Somewhere Not Far from Here, from Playboy, is about some ragged revolutionaries against an unidentified tyranny; its portrayal of men struggling in extremity in mud and blood, in a seemingly hopeless cause, may be hokey but it contrasts sharply and favorably with Dickson’s absurd power fantasy of an effortlessly irresistible conqueror, discussed above. But there are also a number of less meritorious, and sometimes outright distasteful items from the non-SF press, including a remarkably sexist story by Harvey Jacobs, The Girl Who Drew the Gods, from Mademoiselle, of all places.

Summing Up

There’s a lot in this big book that’s perfectly adequate, but not so much that made me seriously glad to have read it, and a fair amount that seems silly, trivial, or distasteful. The best of the lot to my taste are mostly mentioned above; others include Arthur C. Clarke’s Maelstrom II, R.A. Lafferty’s Slow Tuesday Night, Johnny Byrne’s Yesterday’s Gardens, and Walter F. Moudy’s The Survivor. The other two-thirds of the book’s contents are things I don’t imagine I will ever think of again.

Interestingly, Merril herself expresses dissatisfaction with the current state of American SF, which she attributes to the lack of a “combining force” or “focal center”: “We have the writers; we have the markets; we have the readers. But nothing is happening to bring them together.” She compares this situation unfavorably to that in the UK. I don’t find this explanation very convincing. I am convinced that Merril would have a better book if she included a few longer stories and accepted a shorter contents page, and dropped a few of the less substantial items from prestigious sources.

As the Los Angeles Dodgers might say—wait ‘til next year.

by Gideon Marcus

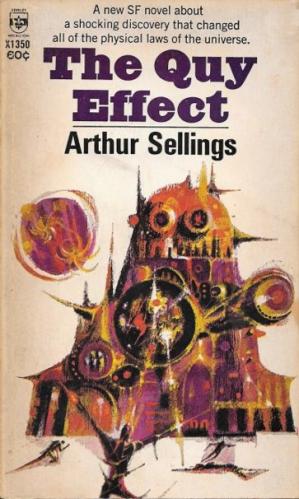

The Quy Effect, by Arthur Sellings

This latest book by short story veteran, Arthur Sellings, starts with a literal bang. A factory has blown up, and Adolphe Quy, an eccentric inventor is the culprit. Seems he was doing experiments with an organic room-temperature superconductor, which got overloaded. But in the process, something even bigger was discovered: practical antigravity.

With a setup like that, you'd think this short novel would be about the effect such an invention would have on humanity. Indeed, for the first forty pages or so, Sellings seems to be taking forever to start the plot. Then you realize you've been anticipating the wrong book. The Quy Effect is about the trials and tribulations of a discredited inventor doing his best to bring to light a technology only he believes in.

Which means, of course, that there were two ways the book could have gone that would have been deeply dissatisfying. One is the John Campbell route, in which it is made obvious that everyone but Quy (pronounced 'kwe') is a moron, and the whole book is a satire of our stupid society that quells the inspirations of unsung geniuses. The other is the British route, which would have Quy end up in an insane asylum, the work being sold as "darkly humourous."

Thankfully, despite Sellings actually being British, he avoids both of these potentialities. Instead, The Quy Effect is a quite interesting set of character studies, one that kept me glued to the pages. It really is not certain throughout the entire book whether or not Quy will succeed. Nor does it seem that the odds are artificially stacked against him. Quy, in many ways, made the bed he's stuck in. Now he has to find his way out.

And while science, for the most part, takes a backseat in this book, I did appreciate the bit where Quy dismisses rocket-powered spaceflight as an economic dead end:

Rockets have got as much future as the dirigible airship had. A certain beauty, a kind of glamour, but too damn dangerous and cumbersome and expensive. Riding space in a pint-sized canister on top of a thousand tons of high explosive—that's not the way. We've got all the energy we want, if we can only use it. We shouldn't have to rely, in this day and age, on crude chemical reaction. Subject a man to ruinous accelerations because we have to carry a giant-size gas tank a minimum distance. What we need is more like a nuclear-powered submarine. Point its noise in the air and float up.

Only time will tell if he is right, but I've made similar assertions since Sputnik. I'm delighted to see the latest results from Explorer satellites, to watch the Olympics live from Tokyo (at 3 A.M., Pacific), and I thrill at grainy videos of spacewalking astronauts. But for the kind of mass space exodus so much of our science fiction is based on, I suspect Sellings' mouthpiece is right—rockets won't do the trick.

Anyway, going by the Budrys yardstick of quality (if one enjoys reading the book, it's good), The Quy Effect is very good, once one accepts it for what it is.

And what it garners is a full four stars.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics; Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Entropy

by Victoria Silverwolf

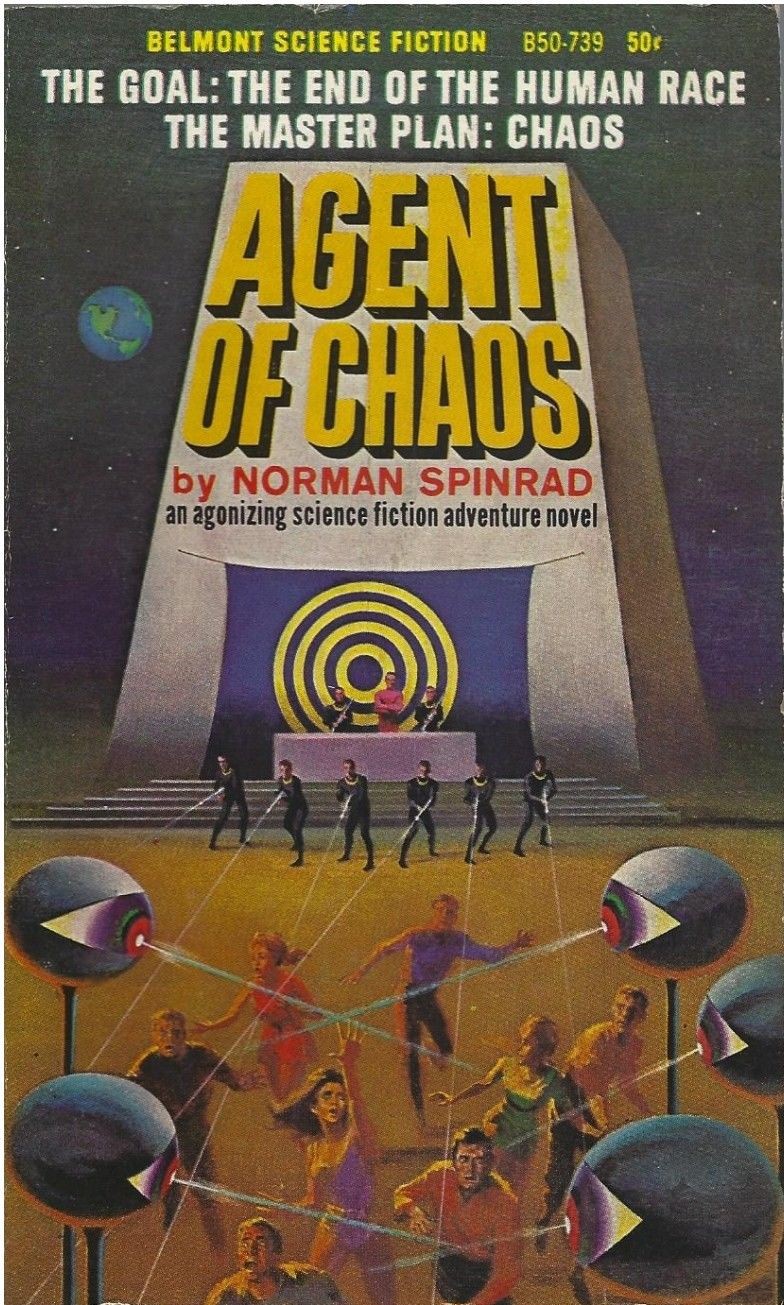

Agent of Chaos, by Norman Spinrad

It wasn't very long ago that I reviewed this young author's first novel. It's obvious that he keeps banging away at the typewriter steadily, because here comes another one.

Anonymous cover art, and a misleading blurb. Ending the human race isn't the goal of anybody in the story. And I don't think that calling a novel agonizing is a way to help sales.

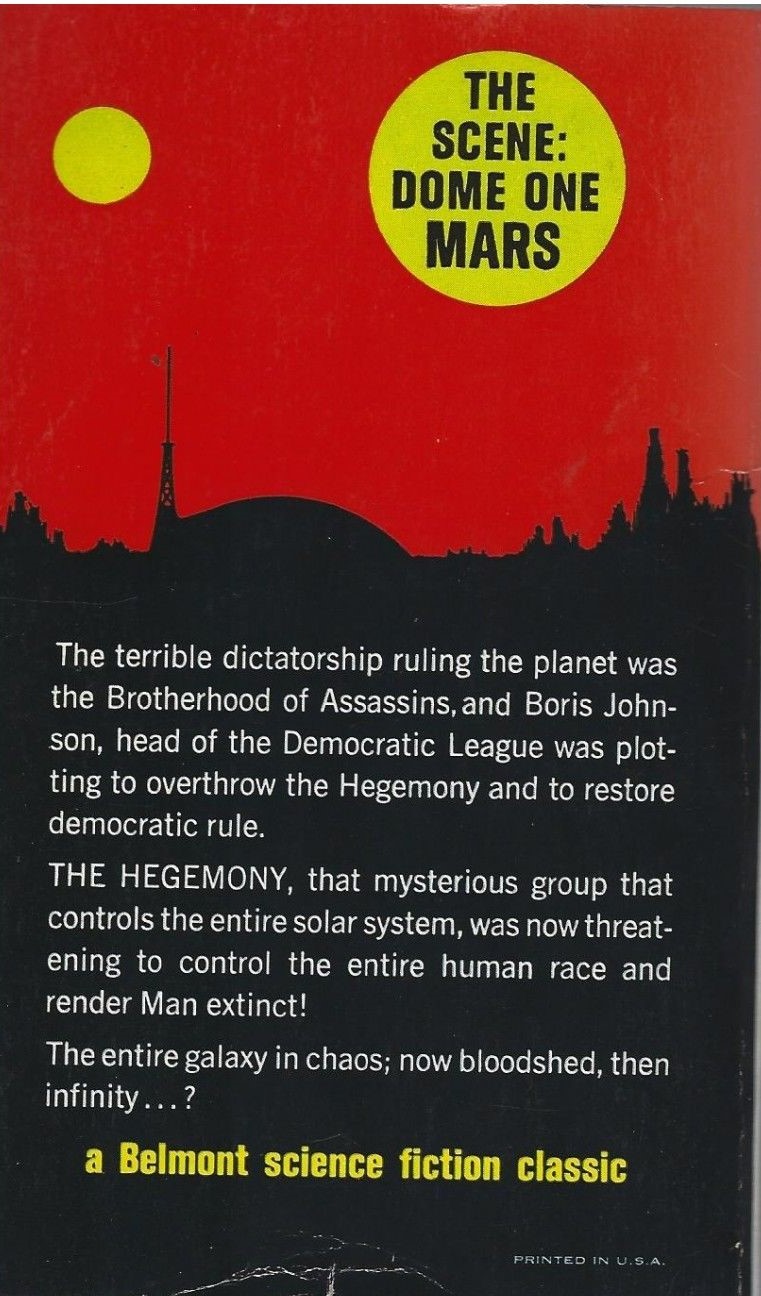

I don't know about you, but when I pick up a book I like to look at the stuff that surrounds the text first. Front and back cover, dedication, preface or introduction, afterword, whatever. Let's flip this paperback over and see if we can learn anything.

Is it really possible for a new book to be a classic?

This blurb isn't much more accurate. The Brotherhood of Assassins isn't the dictatorship; that's the Hegemony. Allow me to explain.

Several centuries in the future, long after the two sides of the Cold War got together to avoid total destruction, the combined government known as the Hegemony rules the solar system. The oligarchy in charge controls every detail in the lives of their subjects, known as Wards. Any violation of the rules is punishable by death. The sheep-like Wards mostly accept this, because the Hegemony offers them peace and prosperity.

The Democratic League is an underground organization, literally and metaphorically. It opposes the Hegemony, and is willing to use violence to overthrow it. The novel begins on Mars, where Boris Johnson, a member of the Democratic League, is part of an elaborate plot to assassinate one of the oligarchs. The motive is to convince the Wards that the Democratic League is a serious threat to the Hegemony.

The third player in this deadly game is the Brotherhood of Assassins. Despite the name, the first thing this bunch does is prevent the killing of the oligarch. Like other things they've done in the past, this action seems completely random. Both the Hegemony and the Democratic League think of the Brotherhood of Assassins as deranged fanatics, dedicated to the philosophical writings of the fictional author Gregor Markowitz. Quotations from this fellow's books, which have titles like The Theory of Social Entropy and Chaos and Culture, introduce each chapter in the novel.

The story jumps around the solar system, with plenty of plots and counterplots, ranging from political intrigue within the oligarchy to mass violence. At times, the book reads like a cross between Ian Fleming and Keith Laumer. But Spinrad is trying to say something more profound, I think.

The Hegemony represents any established Order. The Democratic League represents the opposition to that Order. Ironically, that very opposition becomes part of a new Order. The Brotherhood of Assassins represents Chaos, working against both of the other groups. (In another touch of irony, this often means working with one or the other. Such paradoxes, we're told, are part of Chaos.)

There's a major plot twist about halfway through the novel that I won't reveal here. Suffice to say that something found in a lot of science fiction stories changes the situation drastically, leading to a dramatic ending involving the Ultimate Chaotic Act.

The book certainly held my interest. I'm not sure what to think about all the discussion of Order and Chaos, but it was intriguing. At times the novel is melodramatic. Overly familiar science fiction elements appear frequently, from moving sidewalks to laser guns.

One peculiar thing is that there are no female characters in the book, not even a minor one playing the typical role of the Girl. The closest we get to acknowledging that two sexes exist is a line describing a crowd of Wards as placid, indifferent-looking men and women. The Wards are just cannon fodder, casually slaughtered by the three competing forces, so they remain pretty much faceless.

That reminds me of the fact that there are no Good Guys in this novel. All sides are willing to kill to achieve their goals, including wiping out innocent bystanders. The author's sympathies seem to be with the forces of Chaos, but they definitely have as much blood on their hands as the forces of Order. (Why else would they call themselves the Brotherhood of Assassins?)

Overall, a provocative but frustrating book.

Three stars.

![[January 14, 1967] First batch (January Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670114covers-672x372.jpg)

![[September 14, 1966] All the Old Familiar Places (October 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660912cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 24, 1966] Increments: <i>World's Best Science Fiction: 1966</i>, edited by Donald A. Wollheim and Terry Carr](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/wollheim-66-cover-449x372.png)

![[May 8, 1966] A Respite (June 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660510amz-0666-cover-575x372.png)

![[January 6, 1966] Have Archaic and Beat It Too (February 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/amz-0266-cover-507x372.png)

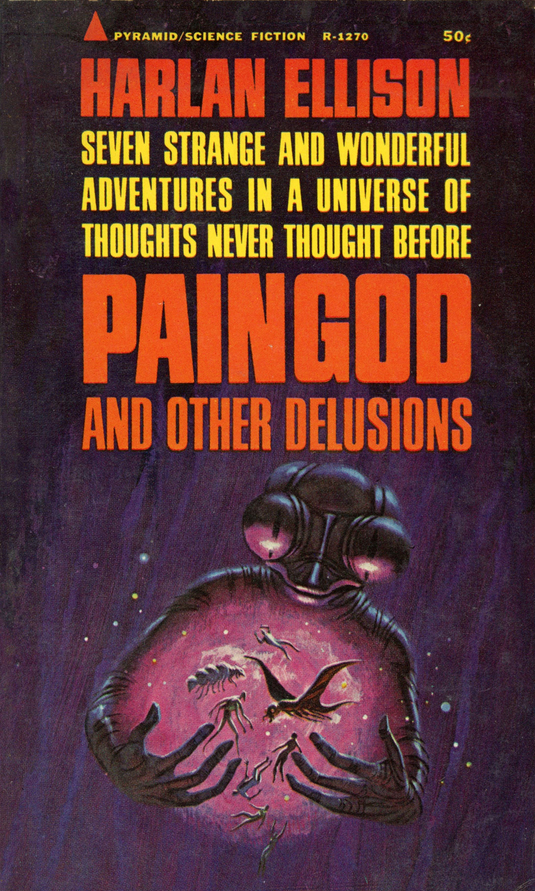

![[December 24, 1965] Gallimaufry <i>du Saison</i>(<i>The Year's best Science Fiction</i> and <i>Paingod and Other Delusions</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651224covers-672x372.jpg)

![[February 24, 1965] Doctors, Hunchbacks and Dunes … <i>New Worlds</i> and <i>Science Fantasy</i>, February/March 1965](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Science-Fantasy-March-1965-672x372.jpg)

[Image by the writer]

[Image by the writer]

![[December 7, 1963] SF or Not SF? That Is the Question (<i>They came from mainstream</i>, 1963 edition)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631207apebook-672x372.jpg)