by Gideon Marcus

Huzzah!

It's hard to believe it was just six years ago that the Renaissance Pleasure Faire started in the suburbs of Los Angeles:

"Counterculture" didn't even have a name yet (I think we were calling it "contraculture"), but already, there were folks weary of the modern age, casting their eyes back to a simpler time. You know, when there were far more things that could kill you, and much fewer opportunities to escape drudgery…

Anyway, I reported on our last foray into the past a couple of years ago. These days, the back-to-then movement is stronger than ever, with the Society for Creative Anachronism exploding (do they have a thousand members now?) and Renaissance Faires catching on. They are a good fit for the Pagans and hippies and folks looking for an escape.

We're not immune to the lure. Here are some scenes from this month's event:

You may recognize the fellow in blue

What really makes the Faire such a delight is the attention to detail. Everywhere you go, there are actors and actress really playing a part, making the whole thing an exercise in living history. Of course, as my "character" styles himself a member of the Habsburg clan, you can bet I razzed the Queen when she paraded by with her foppish retinue.

Nevertheless, I hope the Faire retains its purity, prioritizing the spirit of the event rather than descending into a kind of cynical capitalism. Though, I suppose, that's what the original faires were all about…

Alas!

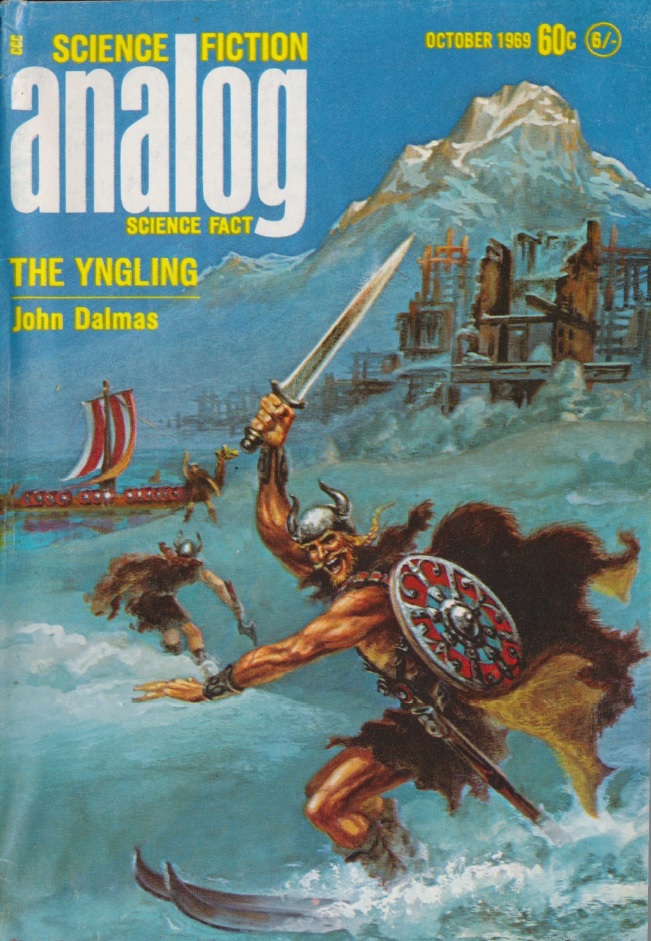

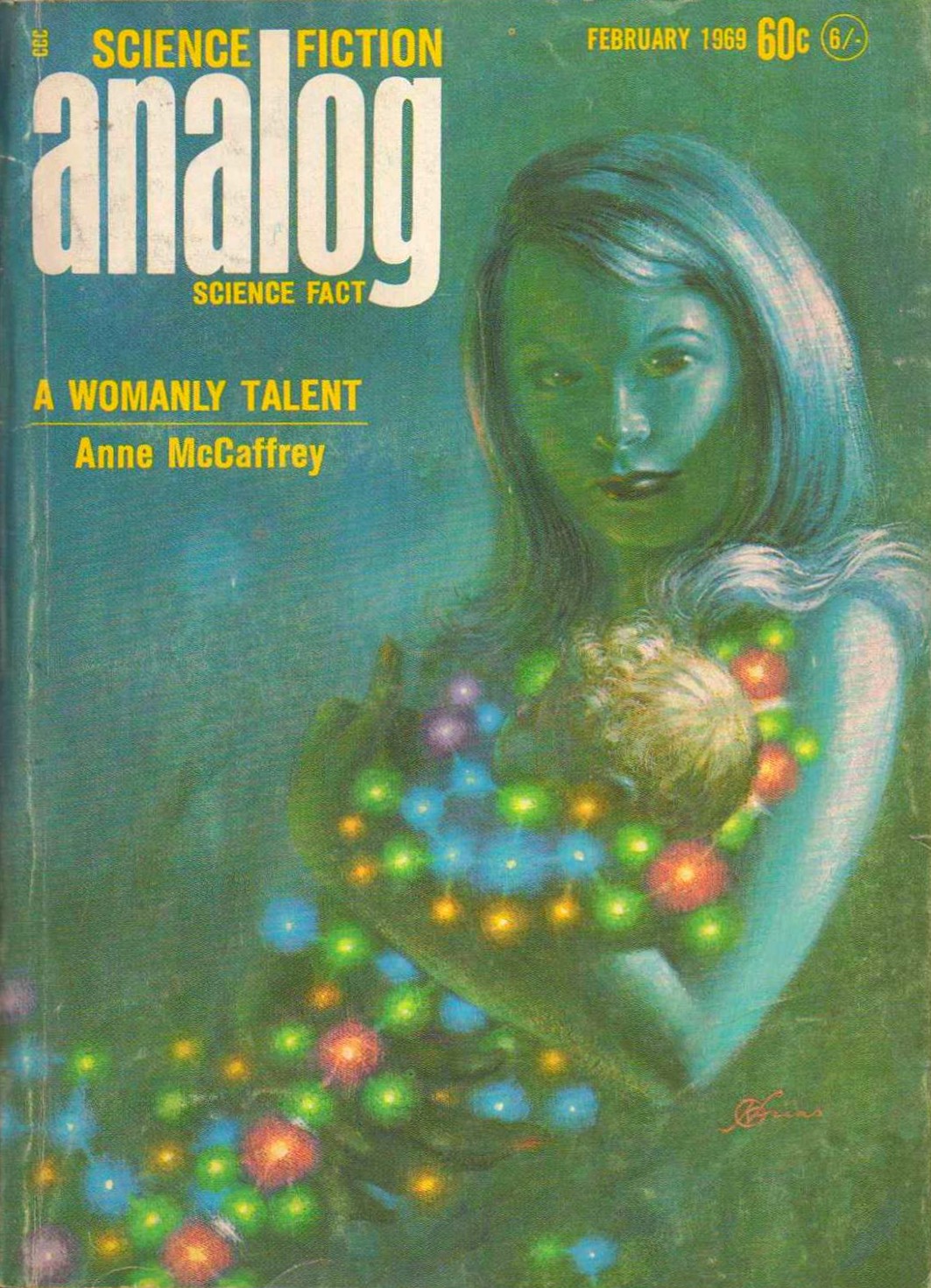

Speaking of cynical capitalism, I feel that Analog editor stays on the job these days just for a paycheck (and a podium for his irrascible editorials—which he then compiles and sells in book form!) While the latest issue isn't terrible, it certainly doesn't scrape the heights it achieved "back in the day."

by Leo Summers

Artifact, by J. B. Clarke

The name of J. B. Clarke is unknown to me. Perhaps he's Arthur Clarke's little brother (sister?) His writing isn't bad, nor even is the premise, but the execution of this first tale of his…

by Leo Summers

A beach ball-sized orb appears in interplanetary space. When an Earth spaceship tries to pick it up, it zips away at faster-than-light speeds a couple of times, as if to demonstrate that it can, and then becomes docile. After it is picked up, the humans assessing the artifact determine that it was deliberately sent to jump-start our technology. But was the rationale benevolent or otherwise?

This would have been a great story had not Clarke explained from the very beginning that the scheme was a plot by the evil Imperium to instigate a diplomatic incident a la the Nazis asserting a Polish attack against the Germans on September 1, 1939. This would give the rapacious aliens legal precedent to annex our planet. Moreover, we learn that an agent of the "Web", the galactic federation of which the Imperium constitutes a small portion, is already on Earth, guiding our assessment of the artifact.

As a result, there's no tension. We know everything will turn out fine. Indeed, it's a strangely un-Campbellian story in that humans aren't the smart ones in the end. But because there are no decisions to be made, no suspense to the outcome, the story falls flat.

Two stars.

Zozzl, by Jackson Burrows

by Leo Summers

This one gets closer to the mark. It stars a big game hunter whose quarry is a telepathic beast. The creature's natural defense is to access your fears and throw pursuers into a nightmare world, repelling them. It's a neat concept, and Burrows (another name with which I am unacquainted), renders the dream sequences quite effectively.

While we learn a bit about our hero's past and motivations, he never really has to solve any puzzles to win his prize. He just wins in the end. There needs to be more.

Still, I really dug the idea, and there's definitely potential for Jackson. Three stars.

Dramatic Mission, by Anne McCaffrey

by Leo Summers

Here's the latest installment of the The Ship Who. This series stars Helva, a profoundly disabled woman who, at a young age, was turned into a cybernetic brain for a starship. Together with a series of "brawns", the human component of the ship's crew, she has been on all kinds of adventures.

In this story, we learn that brain-ships can earn their independence (paying off the debt of their construction) and fly without brawns, and that many vessels strive for this status. But Helva prefers to ride with company—indeed, she insists on it.

Well, her wish is granted. Short-listed for a priority mission to Beta Corvi, Helva is tasked to transport a troupe of actors to a gas giant in that system, where they will perform Romeo and Juliet for a bunch of alien jellyfish in exchange for an important chemical process.

The problem is the drama that unfolds before the drama: Solar Prane, the star, is dying from chronic use of a memory-enhancing drug. His nurse is deeply in love with him. His co-star and ex-lover is jealous and stubbornly insists on sabotaging the production. It is up to Helva to be the grown-up in the room and save the day.

There is so much to like about this story, so many neat, unique things about the setting and characters, that it's a shame McCaffrey can't help getting in her own way. She loves writing waspish, unlikeable characters, and her penchant for including casual, off-putting violence reminds me of what I don't like about Marion Zimmer Bradley.

This is one of those pieces I'd like to see redone by someone more talented and sensitive. Zenna Henderson, maybe, if I wanted to see the soft tones enhanced, or Rosel George Brown (RIP) if I wanted something a little lighter and funnier.

Three stars.

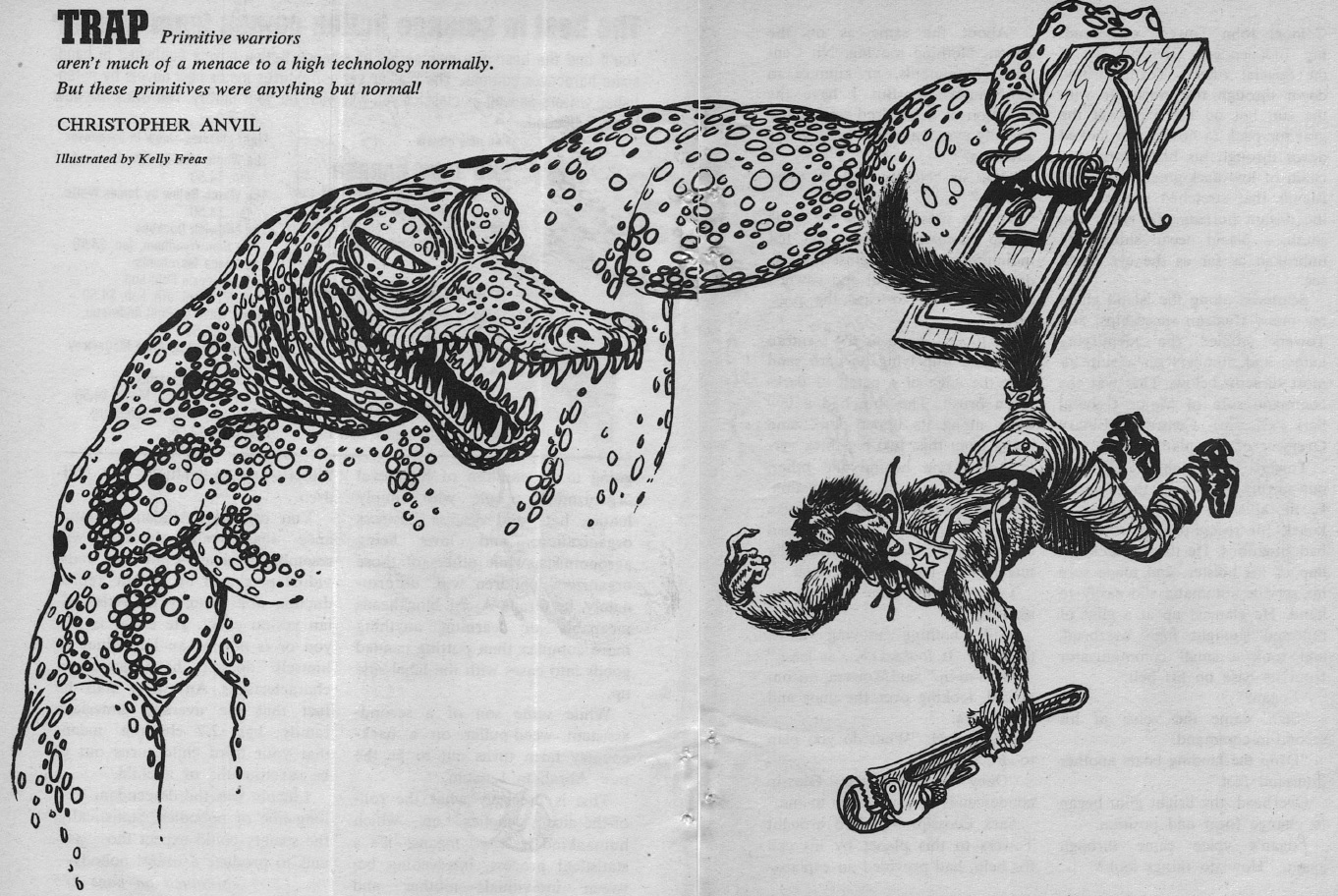

The Nitrocellulose Doormat, by Christopher Anvil

by Peter Skirmat

The planet of Terex has turned into a death trap for the terran Space Force. Invited in to deal with an insurgency problem, a combination of religious proscriptions against advanced technology and a flourishing black market that loots what munitions are allowed in, the human troops are not only made into sitting ducks but laughing stocks.

Enter a canny colonel of the Interstellar Corps, whose bright idea is to suffuse all incoming logistics with explosives so that, when they are stolen, they explode. Deterrent and humiliation, all in one.

It may seem that I've given away the plot…and I have. It's given away fairly early on, and the rest of the story is simply an explication of the plan's success.

I should have liked the story less than I did, but it reads pretty well. Three stars.

The Ghoul Squad, by Harry Harrison

by Leo Summers

A rural sheriff digs in his heels at the notion of government agencies harvesting the organs of newly dead victims of traffic accidents in his jurisdiction. He sticks to his principles even at the cost of his own life, decades later.

This story doesn't say anything Niven hasn't said (much) better in The Organleggers, The Jigsaw Man, and A Gift from Earth.

Two stars.

Jackal's Meal, by Gordon R. Dickson

by Leo Summers

The human sphere of stars has begun to brush against the part of the galaxy claimed by the loosely knit Morah, aliens with a talent for profound modification of bodies, internally and externally. In the middle of sensitive negotiations between the two empires over a contested bit of space, a bipedal creature runs amok at the space dock. It is impossible to determine if the being is a Morah made to look like a human or a human made to look like a Morah. Ultimately, the fate of the two empires rests on this hapless person.

Easily the best story in the issue, both interesting and well written, though it still rates no more than four stars.

Give me the past

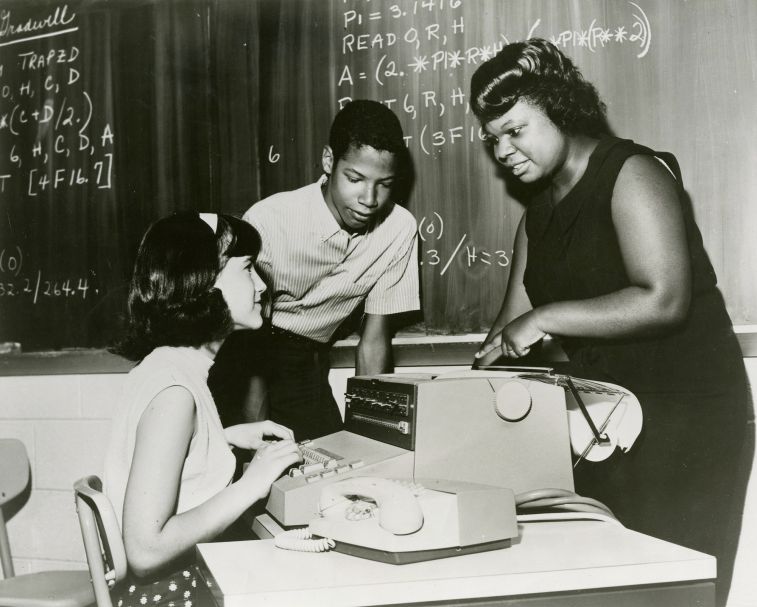

Short story SF appears to be on the decline in general, with only four magazines out this month. Of them, Fantasy and Science Fiction was by far the best, garnering 3.4 stars, but Fantastic and New Worlds both barely made three stars, and Mark, who covers the last mag, has been grumbling about all the newfangled, outré stuff.

As a result, you could fill just one digest-sized magazine with all the good stuff that came out this month. In other statistical news, women produced just 8% of all the new fiction this month.

It's enough to make you long for the (romanticized) good ol' days…but who knows what the future holds?

.jpg)

![[Sep. 30, 1969] Decisions, decisions (October 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/690930cover-651x372.jpg)

![[August 31, 1969] Over (and under) the Moon (September 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/690831analogcover-659x372.jpg)

![[July 31, 1969] Stranger than fiction (August 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/690731analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 30, 1969] Anywhere but here (July 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/690630analogcover-656x372.jpg)

![[May 31, 1969] When eras collide (June 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/690531analogcover-665x372.jpg)

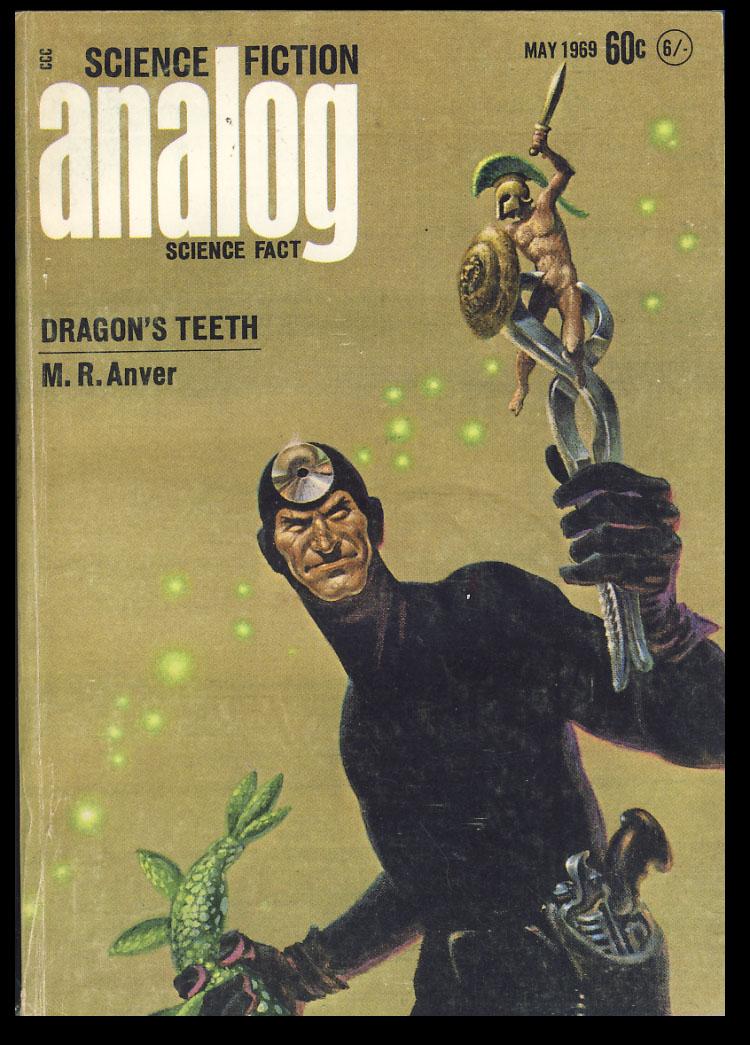

![[April 30, 1969] Eulogies (May 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690430analogcover-672x372.jpg)

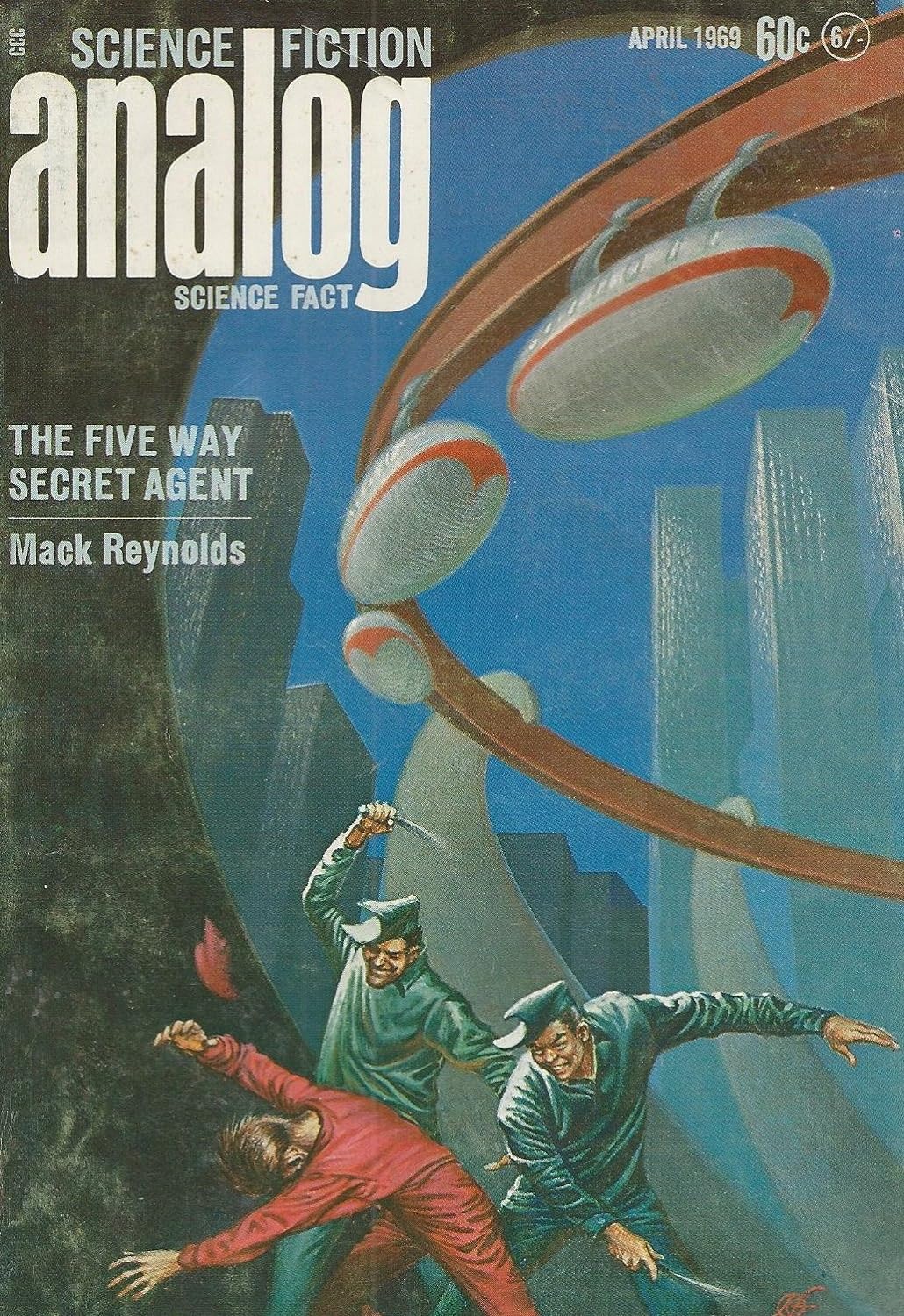

![[April 4, 1969] Hey, Mack! (April 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690331cover-672x372.jpg)

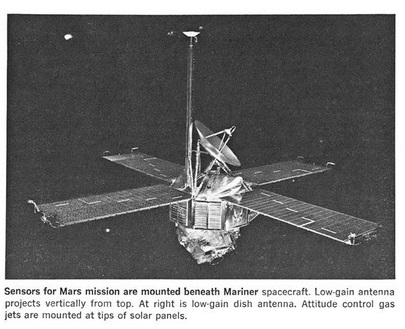

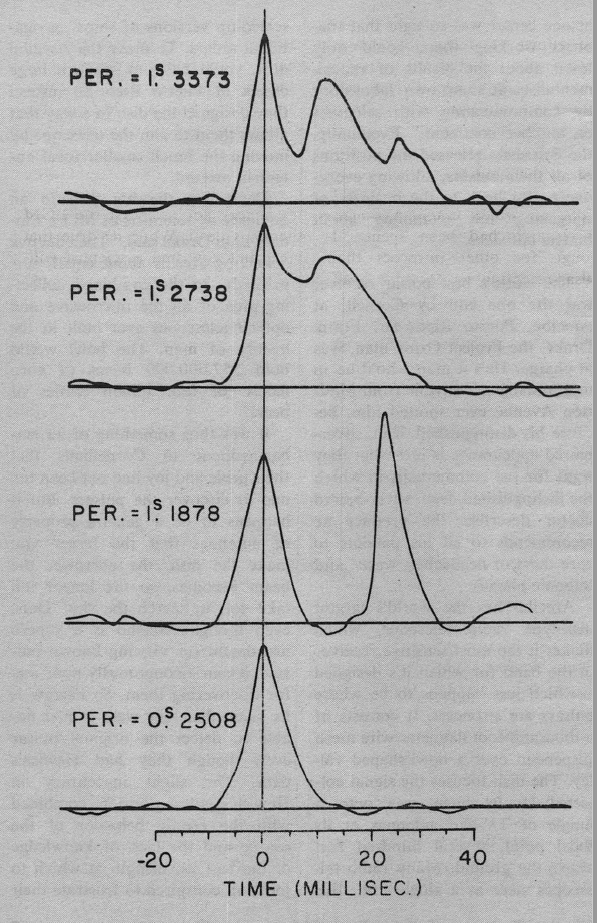

![[March 1, 1969] Beyond this Horizon (March 1969 <i>Analog</i> and Mariner 6)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/690301cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 28, 1969] Slidin' (February 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/690128cover-672x372.jpg)

A Womanly Talent, by Anne McCaffrey

A Womanly Talent, by Anne McCaffrey

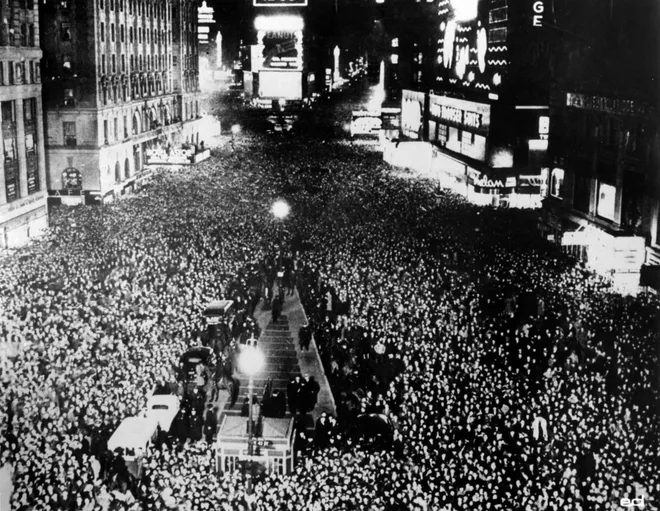

![[December 31, 1968] Auld Lang Syne (January 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/681231cover-672x372.jpg)