by Gideon Marcus

Fading Echoes

It sometimes astounds me how long Galactic Journey has been around. Eight years ago, we covered the launch of Echo 1, a big balloon shot into orbit so that NASA eggheads could use it as a cosmic message relay. More importantly, it was an artificial beacon, proof at a time when the Americans were losing the Space Race, that we had established a visible presence in outer space.

In just a few days, Echo 1 will be no more. Though the air at Echo's altitude is, to terrestrial standards, a fine vacuum, there is enough there to pull at the satellite. For the past eight years, the tug has slowed down Echo, and this month, it will fall out of orbit, plunging into the atmosphere, where it will burn up.

All things must pass, and Echo had a good run, but still, it's a little sad.

Which brings us to this month's issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

Last month, we lost Anthony Boucher, who helmed F&SF for much of the '50s. His term was excellent, and he also wrote some great stories, too, my favorite being The Quest for St. Aquin He was only 56.

Since Boucher's tenure, F&SF has been an inconsistent magazine. There have been good issues of F&SF, and there have been less than good ones. The latest is one of the latter kind, and its underwhelming quality serves only to make us pine all the more for what we've lost.

by Ronald Walotsky

The Consciousness Machine, by Josephine Saxton

Zona Gambier is a mental technician, proficient in the usage of WAWWAR, a device that has revolutionized psychotherapy. It dredges the animus of one's mental dysfunction, bares it to the possessor, and in doing so, cures the ailing person of any psychological malady. It is thus a matter of great consternation when she finds that her patient, Thurston Maxwell's, animus does not seem to correspond to his condition–namely a predilection for sexual assault.

The imagery WAWWAR produces is the story of a teenage boy living ferally, hiding from all of humanity, until he comes across a newborn, still attached to her just-dead mother. He raises the child, somehow providing for it, until she is old enough to be an adoptive sister. Later, as an adult, they become lovers. Finally, they have a child together, completing a kind of circle.

Ultimately, we find out what this story means, and whose animus it actually is. The writing is rather nice, but the explanation at the end is ad hoc, and I certainly wouldn't call the piece science fiction. Science-esque, perhaps.

Three stars.

Of Time and Us, by David R. Bunch

Better poetry than some, worse than others. I'm not sure I care for the sentiment, espousing the futility of humanity against the infinity of chronology.

Three stars.

by Gahan Wilson

The People Trap, by Robert Sheckley

Overpopulation stories have been de rigeur for more than a decade now, to the point where the genre is a bit overripe. Especially given that, according to articles I've been reading lately, the population growth rate has been steadily declining in the First World for most of the '60s. Now, will that continue? There are an awful lot of Baby Boomers coming of age, and perhaps the trend will reverse itself. But it does seem that large families, at least in the West and other developed areas, are falling out of fashion.

Which is why Sheckley's satire of overpopulation stories, in which a mild-mannered father, tired of sharing his one-room flat with five others (with five more on the way), enters a deadly competition, is a breath of fresh air. Along with 60 other participants, he must complete a foot-race through the wilds of New York City, populated by the lowest forms of humanity. His prize: one of the last free-standing acres of land on the continent.

Very quickly, you see that the thing is a lampoon, and as such, it's quite tolerable. Indeed, it's the closest thing to an old-style Sheckley story I've read in a long time, and old-style Sheckley is one of my favorites.

Four stars.

Settle, by Ann MacLeod

A couple buys a fixer-upper. Soon, the man of the house starts losing pieces of himself. First a toe, then a foot, onto his leg and torso, until he is just a head. Still, he goes on repairing elements of the home, determined to make it livable. Eventually, he is just a set of teeth and a bit of brain, mowing the lawn by mouth, until he is crushed under the knee of his toddler son. The end.

Per the editor's preface, this story is about how a money pit takes its toll in flesh from its owners. I'm glad that was explained to me, because otherwise, I'd have no idea.

One star.

Backtracked, by Burt Filer

Author Burt Filer is apparently married to Settle's author, Ann MacLeod. His tale is the superior of the two.

A man in his mid-30s wakes up to find his body ten years older. Apparently, he has "backtracked"–a decade from then, he swapped physical forms with his younger self (which apparently destroys the future incarnation so as to prevent paradoxes). He has no memory of the next ten years, nor why he chose this particular date to come back to.

All he knows is that his polio-crippled leg is now reasonably robust, and that his wife is not altogether happy with his new, somewhat weathered, appearance.

Eventually we do find out what would motivate a man to give up a decade of life, and it's a reasonable justification.

Three stars.

At the Heart of It, by Michael Harrison

This is both an old tale and an old-fashioned tale. It details the tragic story of a bookseller who discovers a profane book, one that teaches the reader the art of transferring one's soul into an inanimate object.

There are no surprises, and the kicker comes at the end, like all its Weird Tales brethren. I imagine this would have been humdrum in the 30s and it certainly doesn't cut the mustard now.

Two stars.

Counting Chromosomes, by Isaac Asimov

The Good Doctor explains the relatively new science of genetics and the role chromosomes, which are essentially punch cards that govern cell reproduction, have in them. He spends a good deal of time on sex chromosomes, and the effects that mutated sex chromosomes have on human beings.

Fascinating stuff, but there is an air of eugenics about his discussion, particularly in calling chromosomally abnormal human beings "defectives" and describing the recent exclusion of Ewa Klobukowska from women's sports on the basis of an extra Y chromosome as a positive development, ensuring competitions remain "sportsmanlike", rubbed me the wrong way.

Three stars.

The Secret of Stonehenge, by Harry Harrison

In this vignette, archaeologists armed with a time-traveling camera send it back to find out why and when Stonehenge was created. Turns out that the camera leaves chronological echoes, afterimages that last long after the camera has departed. Of course, it is these images, that, to primitive Britons, could only have been a sign of the gods, that spurred the creation of Stonehenge.

Harry should know better. We've known since 1963 that Stonehenge was an astronomical calculator, able to predict eclipses and solstices. It was built where it was because it needed to be to function properly.

In any event, the far more exciting (and dangerous) discovery is that long-range time travel can be used to communicate with the past, but this was not touched upon.

Two stars.

Sea Home, by William M. Lee

The first long-term permanent underwater residence has been completed. However, it quickly becomes apparent that Sea Home has a problem: its five long-term crew, already at depth, are undergoing physiological changes. It appears to be linked to the special air mixture they're breathing to alleviate pressure issues; their blend includes oxygen, helium, and sodium hexaflouride–the latter two ingredients serving as a kind of buffer, one very light, and one very heavy.

There's a lot wrong with this story. For one, it's a novelette for a one-gimmick story. Lee tries to add color and reasonably competent writing to hide the fact, but there are simply no mysteries to keep you intrigued beyond the central one.

And the central one is stupid. The premise is that the absence of nitrogen triggers all sorts of biological miracles. Free from the shackles of nitrogen, our bodies become more efficient, our brains get smarter, our skin sprouts tiny fields of gills fer Chrissakes. It reminds me of the early stories about long-term weightlessness, when, because we had no data, sf writers filled in the blanks any way they wanted.

Except we do have data. Gemini 7 was in space for 14 days, its crew breathing a pure, 5psi oxygen atmosphere. None of them got any smarter or developed vacuum-breathing gills or what-have-you.

Dumb. Two stars.

Cithaeronion farewell

As you can see, this issue is sort of like the work of a taxidermist. It looks like F&SF, many of its contents are familiar, but the breath of life is missing. Would that someone new could come along and instill the esteemed publication with the vigor it enjoyed under its past master.

Lest all we have left is fading echoes…

![[May 20, 1968] Dying, deflating, and deorbiting (June 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/680520cover-665x372.jpg)

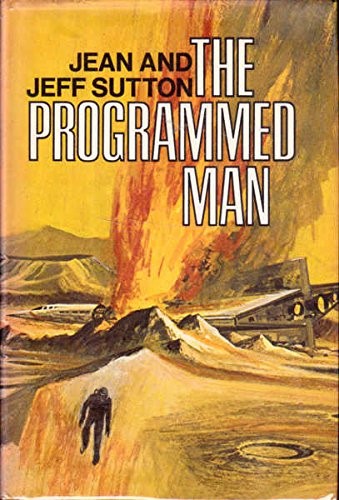

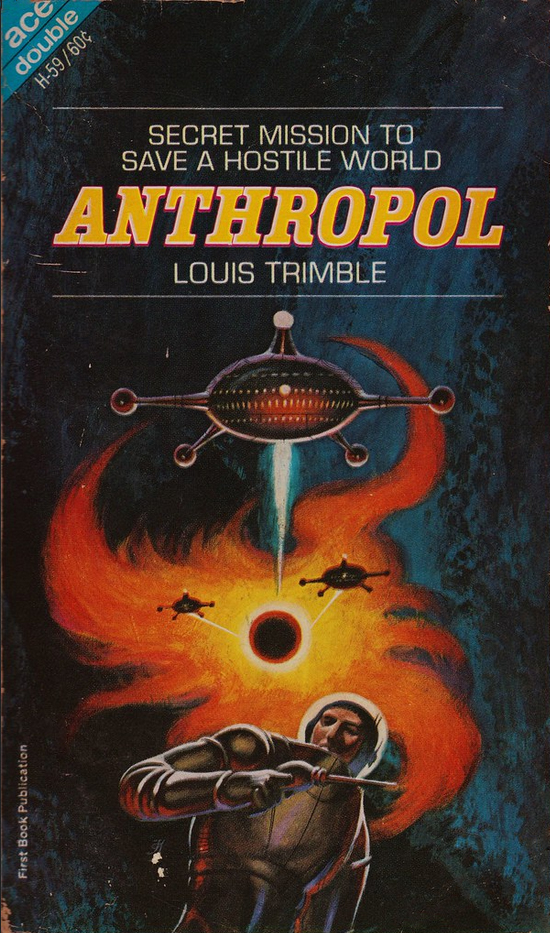

![[May 18, 1968] Four Out of Six Ain't Bad (May 1968 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/680518books-672x372.jpg)

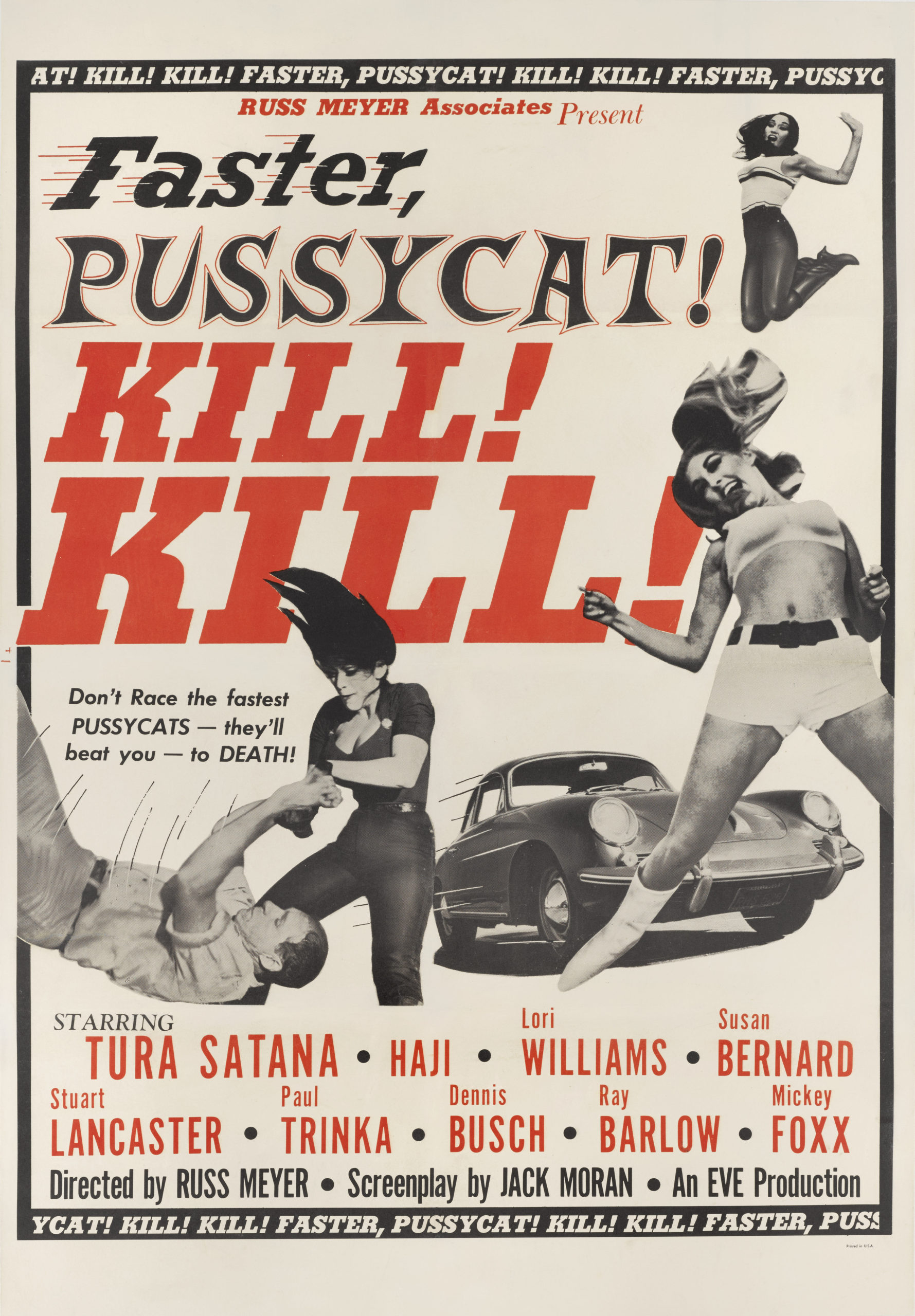

![[May 16, 1968] Counting down, and a blast from the Past (<i>Countdown</i> (1967) and <i>The Time Travelers</i> (1964))](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/680516posters-672x360.jpg)

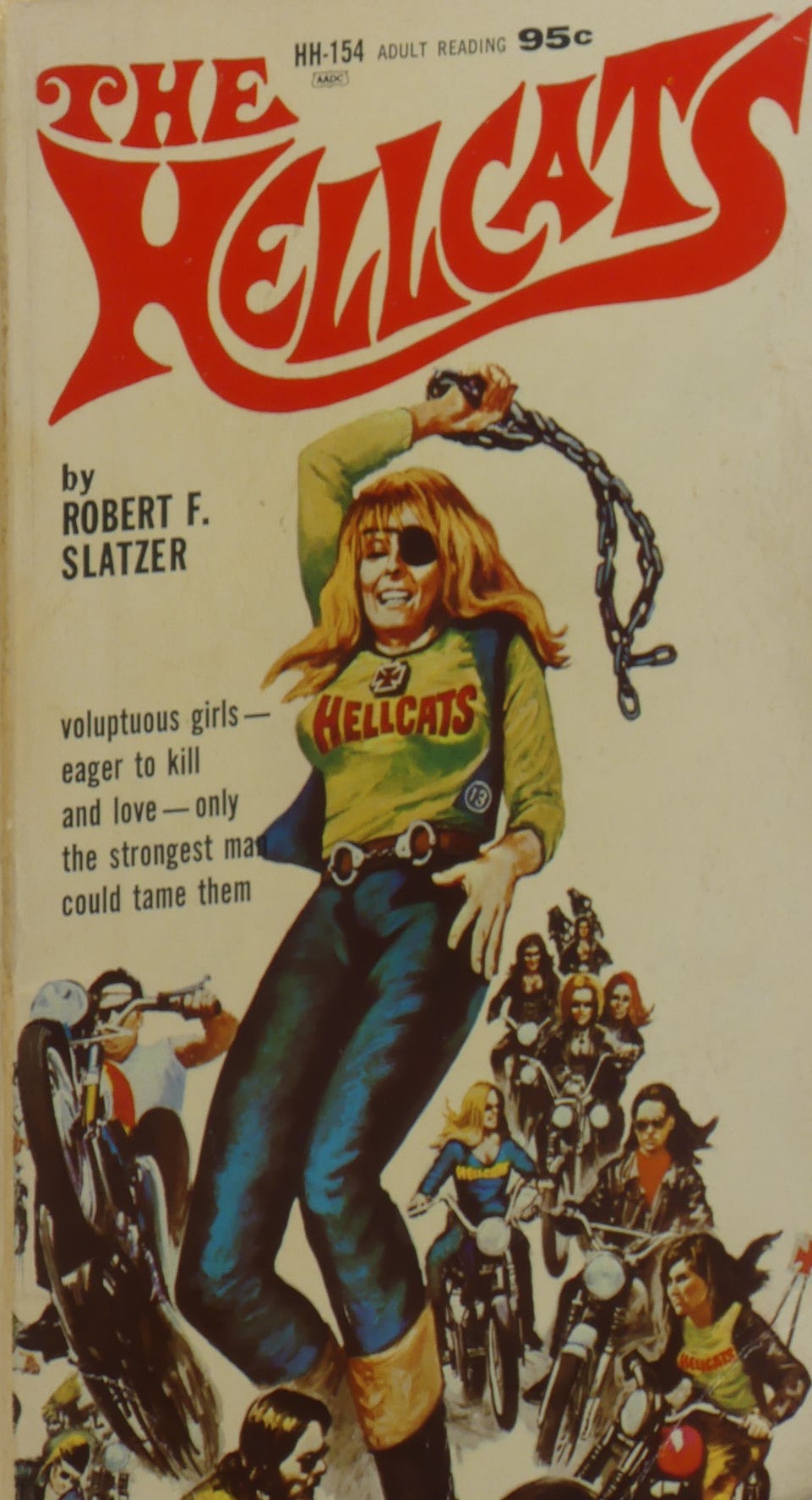

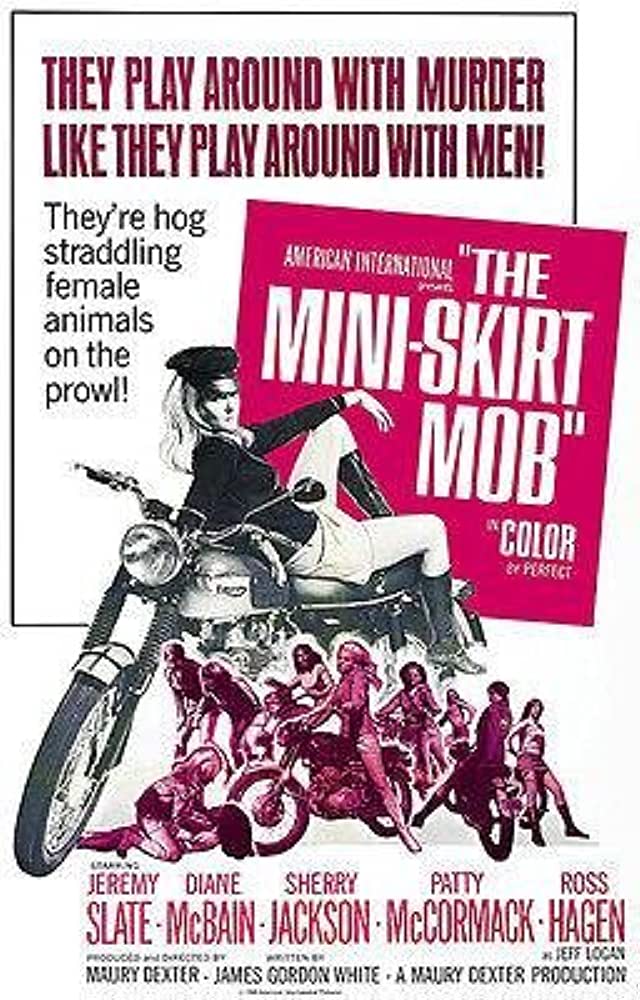

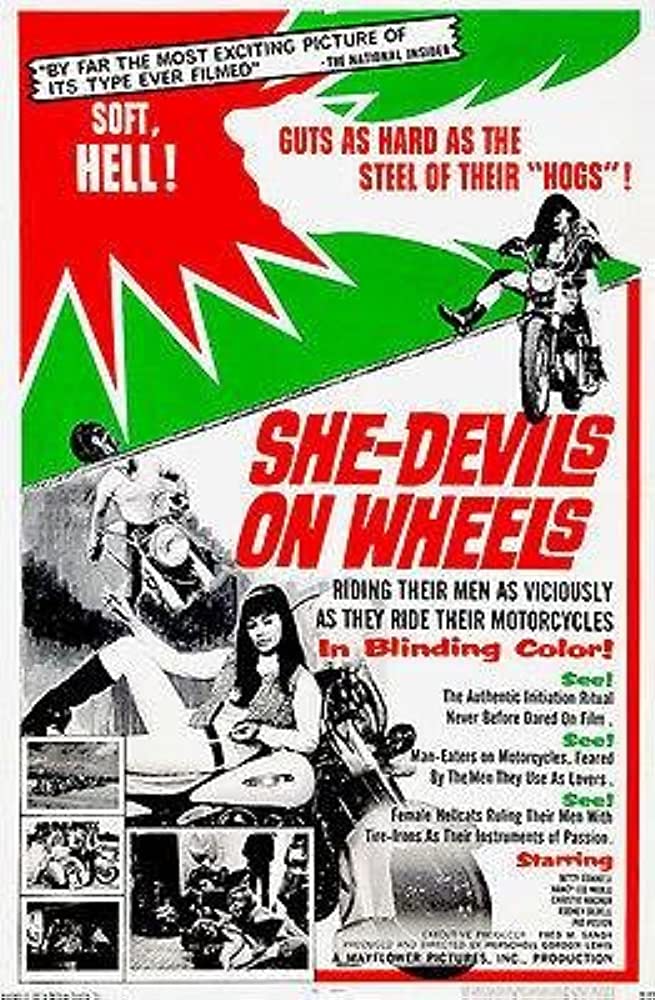

![[May 14, 1968] Bad Girls On Bikes (<i>The Hellcats</i>, <i>The Mini-Skirt Mob</i>, and <i>She-Devils On Wheels</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Untitled-2-672x372.jpg)

![[May 10, 1968] Horse race (June 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/680510cover-393x372.jpg)

![[May 8, 1968] A Visit to Thirdmancon, the 1968 British Science Fiction Convention](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/680426-ThirdManCon-Alison-Scott-672x372.png)

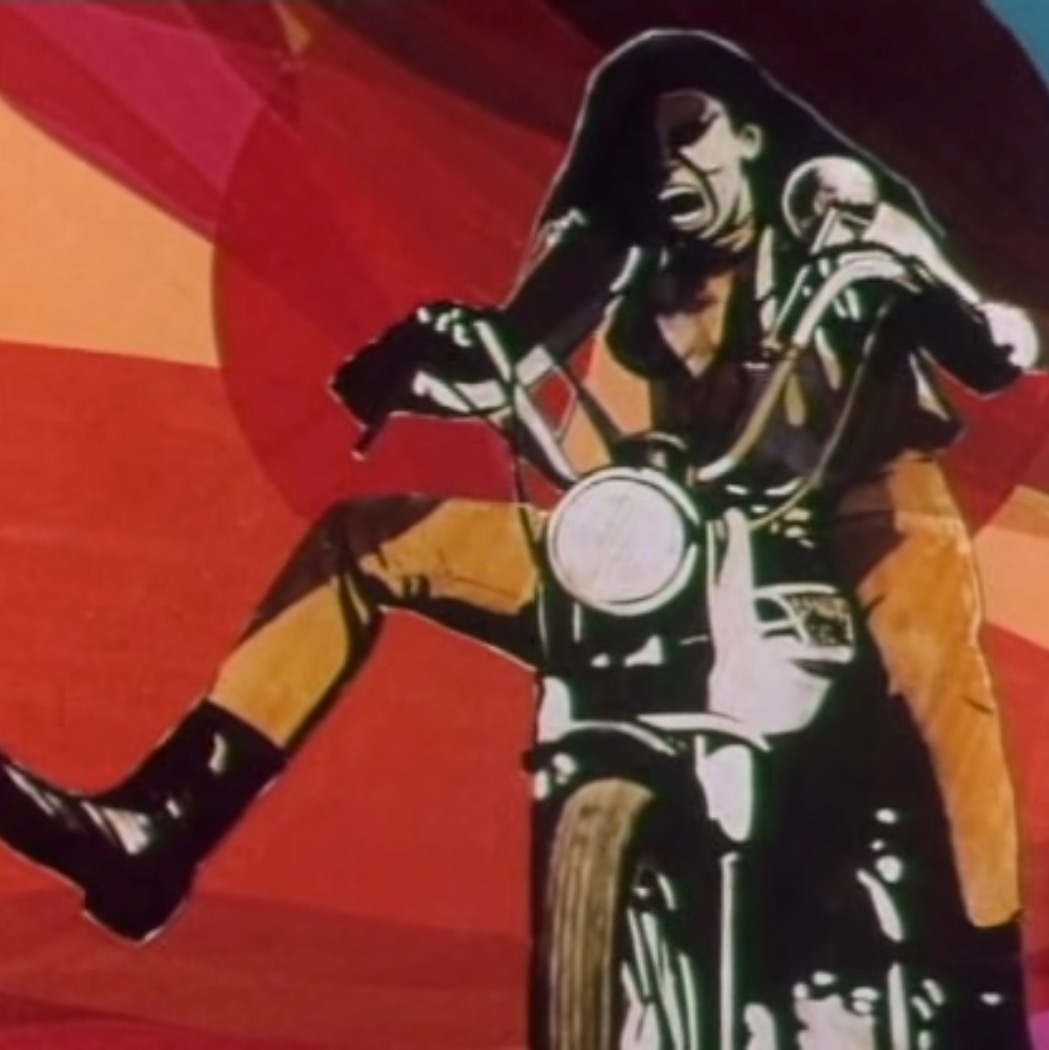

![[May 6, 1968] Does Whatever A Spider Can! (Spider-Man Cartoon)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/sm67-1-672x372.jpg)

Once again, the notorious Grantray-Lawrence studio was behind this quickie cheapie, as they were behind the Super-Heroes show. G-L obviously had a few more dollars to spend on Spider-Man, but twice zero is still zero, and the production values doom this show to be second-rate.

Once again, the notorious Grantray-Lawrence studio was behind this quickie cheapie, as they were behind the Super-Heroes show. G-L obviously had a few more dollars to spend on Spider-Man, but twice zero is still zero, and the production values doom this show to be second-rate.

![[May 2, 1968] The Thing with Feathers (June 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/IF-Cover-1968-06-672x372.jpg)

l. New Governor-General Banja Tejan Sie. r. New Prime Minister Siaka Stevens.

l. New Governor-General Banja Tejan Sie. r. New Prime Minister Siaka Stevens. No one has ever seen the prison of Brass from the outside. Art by Vaughn Bodé

No one has ever seen the prison of Brass from the outside. Art by Vaughn Bodé![[April 30, 1968] (Partial) success stories (May 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/680430cover-672x372.jpg)