by Gideon Marcus

We've had a bit of a backlog of books here at the editorial desk, and the only remedy was to have two back-to-back Galactoscopes. Luckily, summer is slow season for TV, and thus the schedule opens up a bit. Sometimes, our book review column comprises a clutch of mediocrities. This time around, the disparity in quality was abnormally high–mostly thanks (no thanks!) to the debut novel by one Piers Anthony…

Chthon, by Piers Anthony

Imagine a world where genetic modification has created a monstrous race of humans. The women are near-immortal semi-telepaths, but they suffer from an emotional inversion: they only feel love and joy when men express hate and pain. You can imagine how warped the ensuing society must be, the females doomed to solicit violence from their partners, the men compelled to express their every animalistic whim on them. One woman of this race escapes this planet, but, a slave to her make-up, cannot escape her wretched fate. Thus, she marries a man wracked with guilt from the death of his first wife in childbirth. When his love for the alien woman becomes unalloyed, she must leave, but not before she bears a child.

But the alien woman still requires love, twisted, painful love, to live. So she seduces her own son, thus ensuring his passion for his mother will always be the appropriate mix of pleasure and pain, and they can live happily ever after.

In-between these episodes, the story takes place on Chthon, the hellish underground garnet mine whence the son is sentenced for murder. Naked and toolless, he must devise an escape, resorting to treachery, violence, rapine, and cannibalism. Of course, we know he will escape because author Piers Anthony elected to tell the story in a ping-pong flashback/flashforward style, starting and ending with scenes on Chthon.

This is a terrible book.

The premise, fundamentally implausible, seems tailored to indulge a male id-fantasy. We already have a problem in our current society whereby women are "othered" into a different species: vain, frivolous, subservient, sinister, yet desirable. With Chthon, Anthony comes up with a scientificititious explanation for why his starring woman must be that kind of creature. Not that the other women in the novel fare much better, consisting of a slave and vicious fellow Chthonian prisoners.

I'm sure Anthony would say that the book is unpleasant because it bares the human (i.e. male) soul, revealing the sordid mess underneath we'd rather not acknowledge. That all men desire to possess our mothers, rape our partners. That hate is really the purest kind of love.

Mr. Anthony needs professional help. Chthon is an odious turd, and I suspect its author is, too. One star, and winner of this year's "Queen Bee" award.

by Cora Buhlert

Like our esteemed host, I also had the misfortune of reading Chthon. I spotted the paperback in my friendly local import store and was intrigued enough by the unusual title to pull it out of the spinner rack. And while I have not read much by Piers Anthony – and am now unlikely to ever read more – he is one of Cele Goldsmith Lalli's discoveries and she normally has a good eye for authors. The blurb on the back of the slim paperback – promising a tale of an inescapable space prison and a man sent there for pursuing a forbidden love affair – sealed the deal, because I am a sucker for space prison stories.

The scenes set on Chthon, the hellish prison planet cum garnet mine, are indeed the one redeeming grace of this novel. Genuinely atmospheric and visceral, they immediately drew me in. However, even these scenes are marred by what will become a recurrent problem, namely the fact that every single woman protagonist Aton Five meets wants to have sex with him, while Aton manfully refuses, because there can only be one woman for him: Malice the forbidden minionette (i.e. his mother, though he doesn't know that yet).

Scenes of Aton's life leading up to his incarceration are interspersed with the scenes on Chthon. Again, there are some interesting ideas here, such as hvee flowers which Aton's family cultivates and which can detect true love. And once again, the good ideas are marred by off-putting sex scenes, such as fourteen-year-old Aton trying to have sex with a thirteen-year-old neighbour girl and failing because human girls have anatomy and fluids, unlike his idealized vision of minionettes.

When Aton rapes a woman on Chthon, the book came close to hitting the wall and I only prevailed because I had promised to review it for the Journey. The book did actually hit the wall – and considering how expensive import paperbacks are, that's saying something – once we got to the planet of the minionettes, genetically engineered to be masochists and enjoy pain, and of course the final twist of just why Aton has been so obsessed with Malice since he was seven years old and that their "love" is forbidden for a very good reason.

Honestly, this is a terrible book. The sexual revolution and the New Wave have made it easier for science fiction to address formerly taboo subjects like sexuality. But just because authors can write about sex now, doesn't necessarily mean that they should foist their sexual fantasies upon unsuspecting readers, particularly the kind Piers Anthony appears to harbor.

Zero stars. Stay away!

Belmont Double 5F0-759

Belmont Publishing has decided to take on the Ace Double is a flaccid sort of way by combining two novellas (calling them "two complete novels") in one thin volume. This is the first result.

Peril of the Starmen, by Kris Neville

First up Kris Neville's 1954 story, Peril of the Starmen, which first appeared in the magazine Imagination. You're welcome to give it a read if you like.

The Flame of Iridar, by Lin Carter

Considering how harsh I was on The Star Magicians, I was surprised to find that Lin Carter's The Flame of Iridar, published as an Ace Double knock-off by Belmont together with Peril of the Starmen by Kris Neville, reprinted from the January 1954 issue of Imagination, was the better of the two books I read this month. Not that this is a high bar to clear, considering how utterly terrible Chthon was.

That said, Lin Carter's writing has improved since last year's The Star Magicians. True, his prose is still overly purple – thews are inevitably iron and mighty, blood and pain are inevitably scarlet, and female breasts are inevitably described by inappropriate adjectives – and Carter is still oddly preoccupied with lovingly describing his protagonist's manly physique. However, at least Carter remembers who his protagonist is this time around.

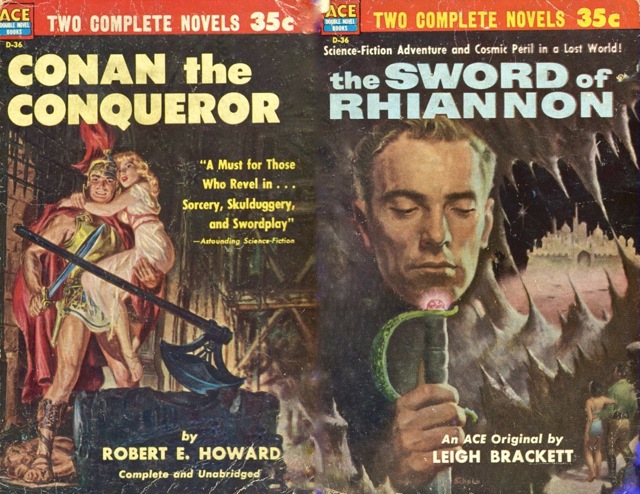

The protagonist is one Chandar of Orm, a deposed prince turned pirate on ancient Mars, when it still had oceans. If this setting seems familiar, that's because it is, borrowed wholesale form Leigh Brackett's much superior 1949 novel Sea-Kings of Mars, better known as The Sword of Rhiannon, the title under which it was published as the very first STF Ace Double back in 1953 together with another excellent fantasy adventure, Conan the Conqueror by Robert E. Howard. And indeed, Carter acknowledges this influence and dedicates The Flame of Iridar to Leigh Brackett and her husband Edmond Hamilton.

The opening of the novel finds Chandar of Orm in deep trouble. After a successful career as a pirate, he has been captured by the evil warlord Niamnon (occasionally spelled Niamnor in what I hope is not indicative of the quality of Belmont's copy-editing), the man who slaughtered Chandar's entire family in front the then twelve-year-old boy's eyes, and has been sentenced to die in Niamnon's arena, a fate Chandar himself imagines as follows:

A few more hours of darkness, and then the blinding morning sun on the arena sands… a few moments of scarlet pain… and he would rest… forever.

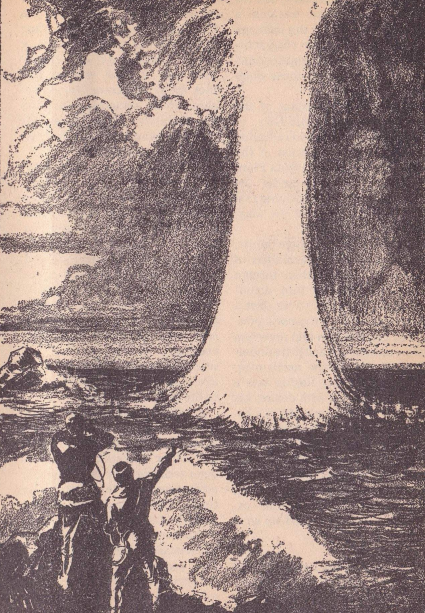

However, before it can come to that, Chandar and his comrade-in-arms Bram are freed by the enchanter Sarkond of K'thom, advisor to none other than King Niamnon himself. Sarkond also helpfully reveals Niamnon's plans of conquest and promises to take Chandar back to his pirate comrades. And in return, he only asks for a little favour. Use the Axe of Orm, a magical weapon that can only be wielded by a member of Chandar's family, to pierce the enchanted Wall of Ice that surrounds the magical realm of Iophar. What can possibly go wrong?

To no one's surprise, Sarkond double-crosses Chandar as soon as Chandar has fulfilled his purpose and hacked through the Wall of Ice. However, Chandar is saved by Meliander, exiled brother of the villainous King Niamnon.

What follows is an epic clash of the forces of good and evil. Chandar also gets revenge on Niamnon and his throne back. Furthermore, he gets entangled with two women, the witch Mnadis, whose breasts are "high and proud", and Llys, Queen of Iophar, whose breasts are "sweet and virginal". Three guesses with which of the two ladies Chandar ends up.

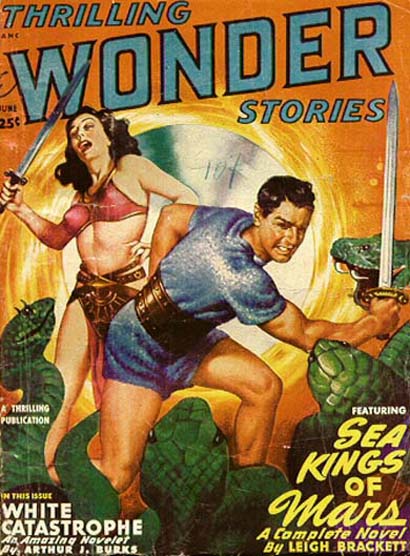

In many ways, The Flame of Iridar feels like the sort of swashbuckling planetary adventure that might have been found in the pages of Planet Stories or Thrilling Wonder Stories twenty years ago. It's not as good as Leigh Brackett or Edmond Hamilton at their best, but then who is?

An entertaining adventure that feels like a throwback to the pulp era. Three stars.

by Gideon Marcus

And to continue our positive mood (because after Chthon, a double dose is necessary), let's all dig on Ted White's latest novel:

The Jewels of Elsewhen, by Ted White

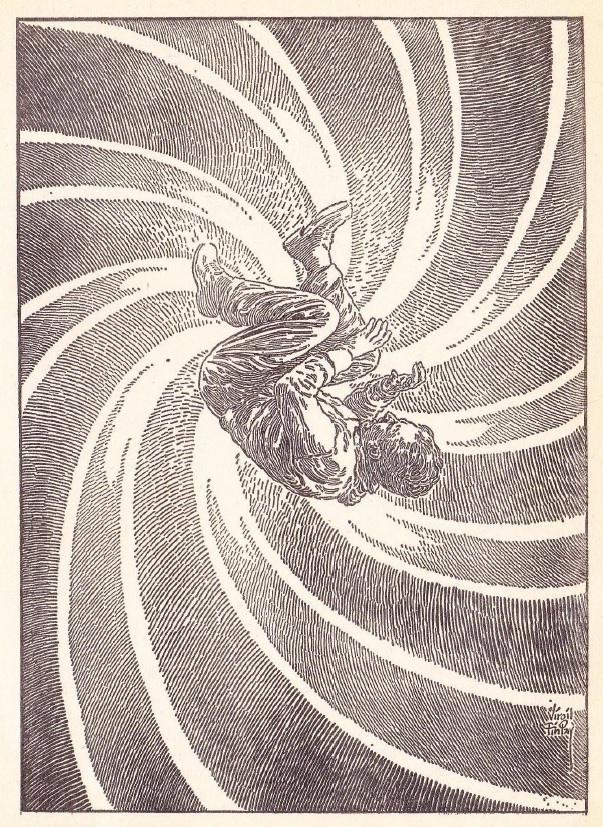

Arthur Ficarra, an exhausted ex-beat cop-cum-desk-sergeant, just wants his subway ride to end so he can go to sleep after an overlong shift. But when he responds to the death rattle of a fellow passenger, he discovers to his horror that the stricken man, and everyone on the train but one, is just a mannequin, the train a cardboard model. Only Arthur and a young woman named Kim remain human. Indeed, it turns out they are now the only living things in all of New York City.

But this is not the Big Apple they remember. It is subtly changed, freshly painted, with hollow buildings. Almost a model of itself. And it is disintegrating…

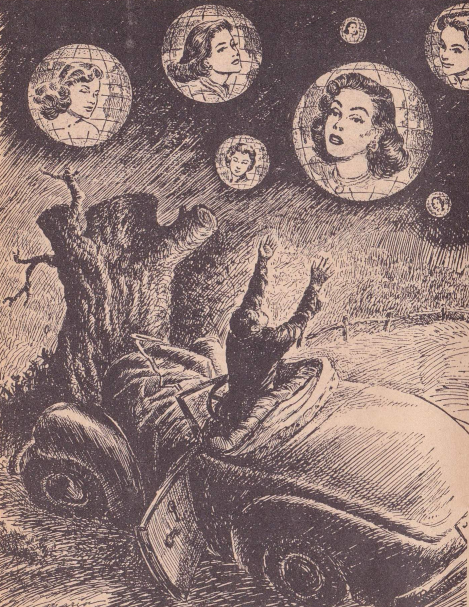

Escape takes them on a whirlwind tour of alternate timelines, the common element of which is that the people speak some variety of Italian. There also is the sense of deliberate manufacture, as well as a shepherding of world events by a secret society of cloaked individuals. Arthur and Kim must solve the riddle of these artificial universes before they are captured and dispatched by these caretakers.

I came in without knowing what to expect. Sure, Rose Benton gave White's last book, Android Avenger, a whopping five stars, but I'd never gotten a chance to read it. All I really knew about the author was that he doesn't like Star Trek (per his column in the latest issue of the Yandro fanzine), he helps edit Fantasy and Science Fiction, and he's chair of the NyCon 3 committee.

I really dug this book. It's written in a punchy but understated style well-suited to mainstream fiction; indeed, I have to wonder if White makes most of his money out of the genre. He's certainly good enough. Arthur and Kim are compelling, strong characters, and the divergent timetracks are nicely detailed. I was in recent correspondence with Ted, and I mentioned that the book reminded me a bit of Laumer's Worlds of the Imperium books. He replied that the resemblance was intentional, and that Laumer had a strong influence on him.

If anything, I like White's even better! Four stars.

![[July 18, 1967] Highs and Lows (July Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670718covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 16, 1967] The Weird and the Surprising (July 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670716covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 14, 1967] The Beat Goes On (August 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/amz-0867-cover-383x372.png)

![[July 10, 1967] Return to Collinsport (the gothic soap opera, <i>Dark Shadows</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/BarnabasPortrait-1-620x372.png)

![[July 8, 1967] Family lines (August 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670710cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 6, 1967] Humour, British-style (<i>Carry on Screaming</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670706poster-672x372.jpg)

![[July 4, 1967] Angels and Demons (August 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/IF-1967-08-Cover-645x372.jpg)

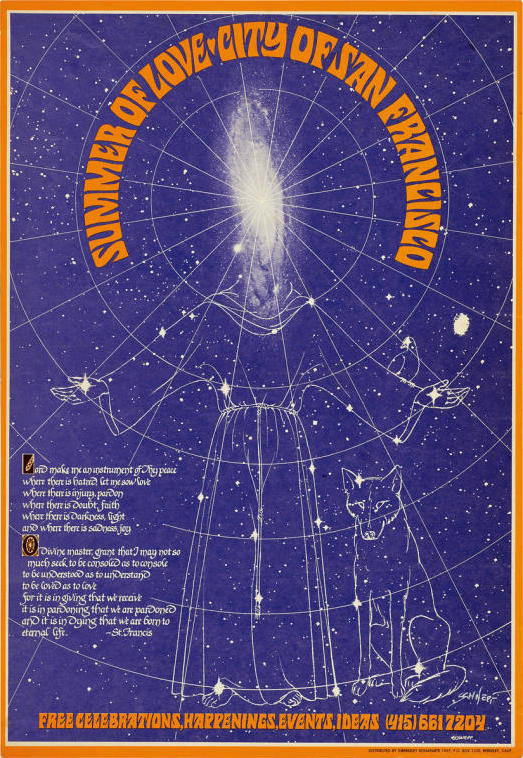

The official poster created by Bob Schnepf

The official poster created by Bob Schnepf The festival was delayed one week due to bad weather.

The festival was delayed one week due to bad weather. This poster is a good example of the new psychedelic art style.

This poster is a good example of the new psychedelic art style. Hippie Randall DeLeon greets the sun and makes the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle.

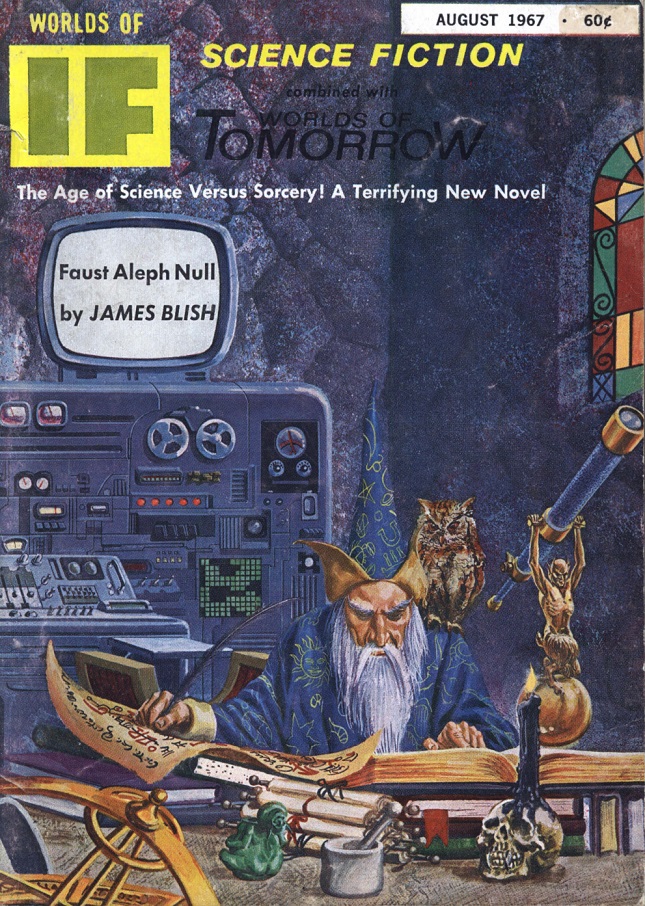

Hippie Randall DeLeon greets the sun and makes the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle. That’s not quite how black magic works in the new Blish novel, but it ought to be. Art by Morrow

That’s not quite how black magic works in the new Blish novel, but it ought to be. Art by Morrow![[July 2, 1967] An Explosive Ending (<i>Doctor Who</i>: THE EVIL OF THE DALEKS [Part 2])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670702emperor-672x372.jpg)

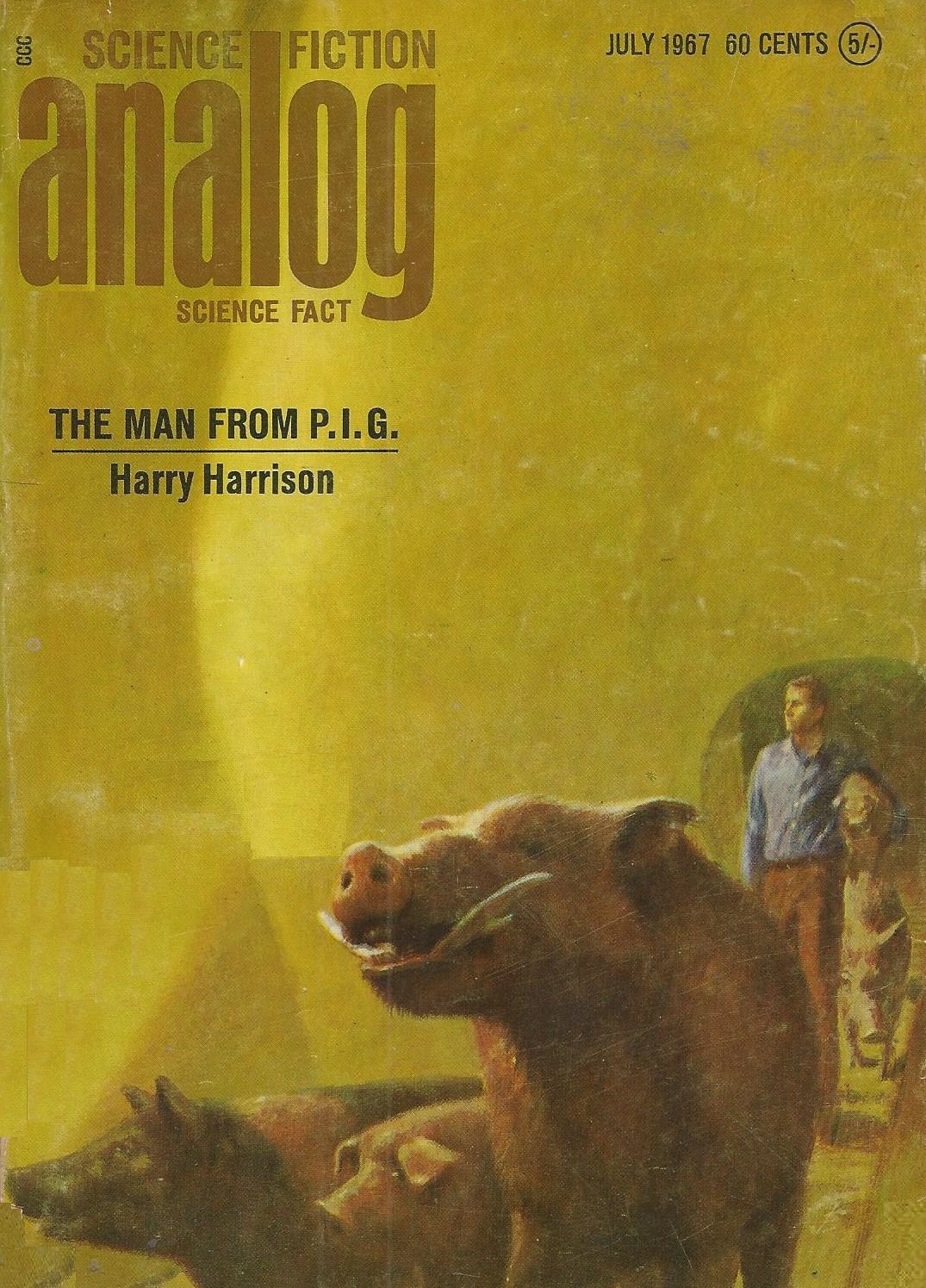

![[June 30, 1967] Bad trip (July 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670630cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 28, 1967] Around the World in Two Seconds (<i>Our World</i> Global Satellite Broadcast)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Our-World-1.png)