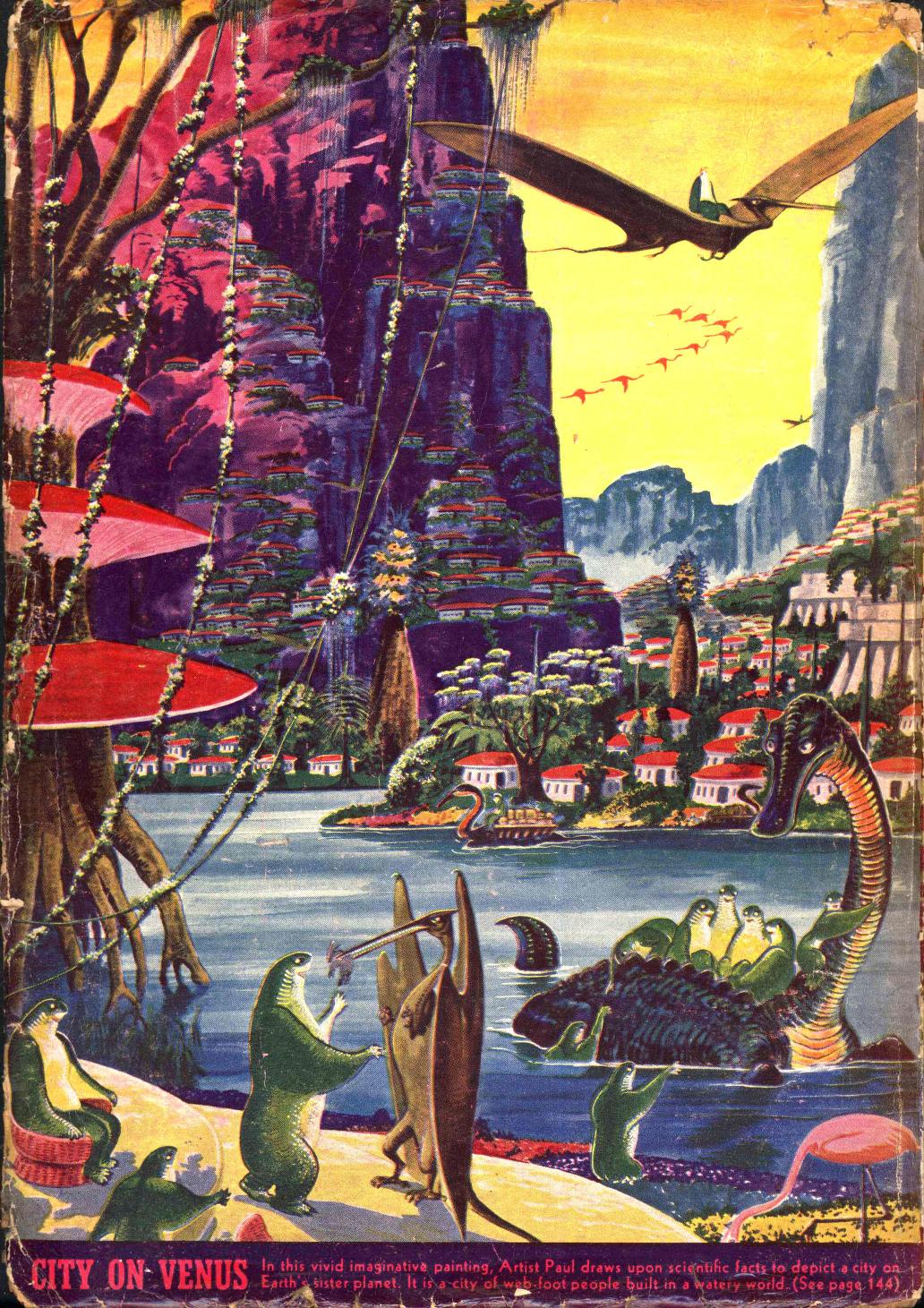

by Victoria Silverwolf

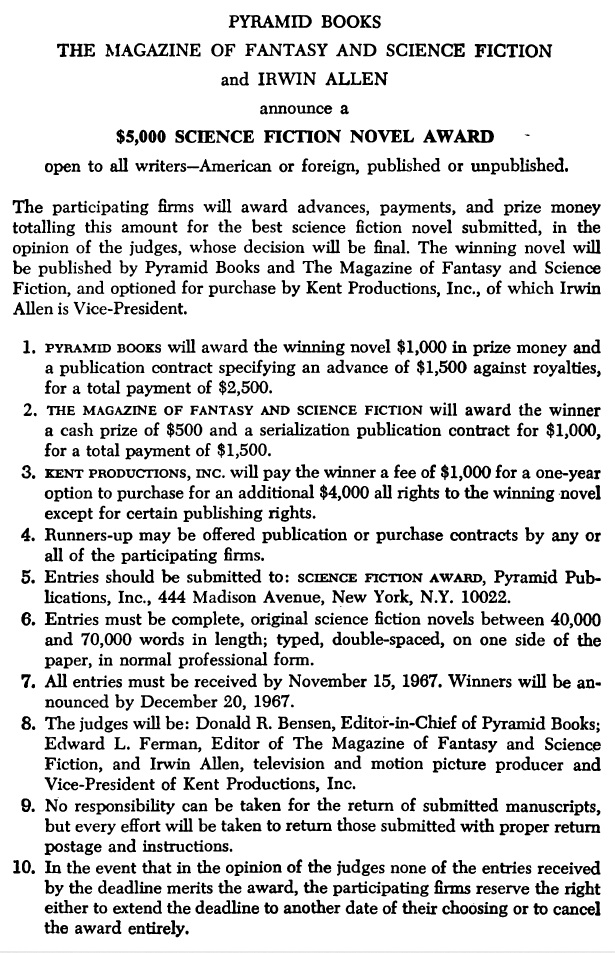

If any more proof is needed that rock 'n' roll now dominates the American popular music scene, here it is: a couple of days ago, radio station KMPX in San Francisco (106.9 on your FM dial, for those of you near the city by the bay) started playing a wide variety of rock music (as opposed to the usual Top Forty hits) twenty-four hours a day. As far as I know, it's the first station in the USA to do so.

Tom "Big Daddy" Donahue, programming director for KMPX.

I live a very long way from Frisco, so I won't be able to pick up their signal.

Appropriately, the lead story in the latest issue of Fantastic features the inability to establish contact over a vast distance as a major plot point. As we'll see, other stories in the magazine also deal with difficulties in communication.

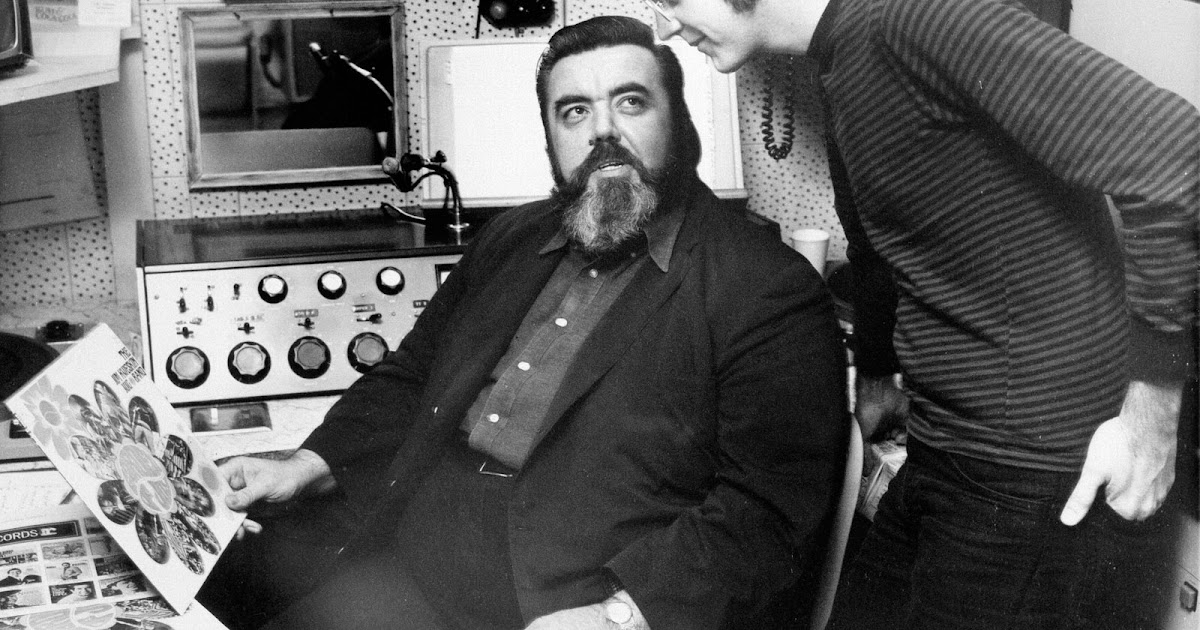

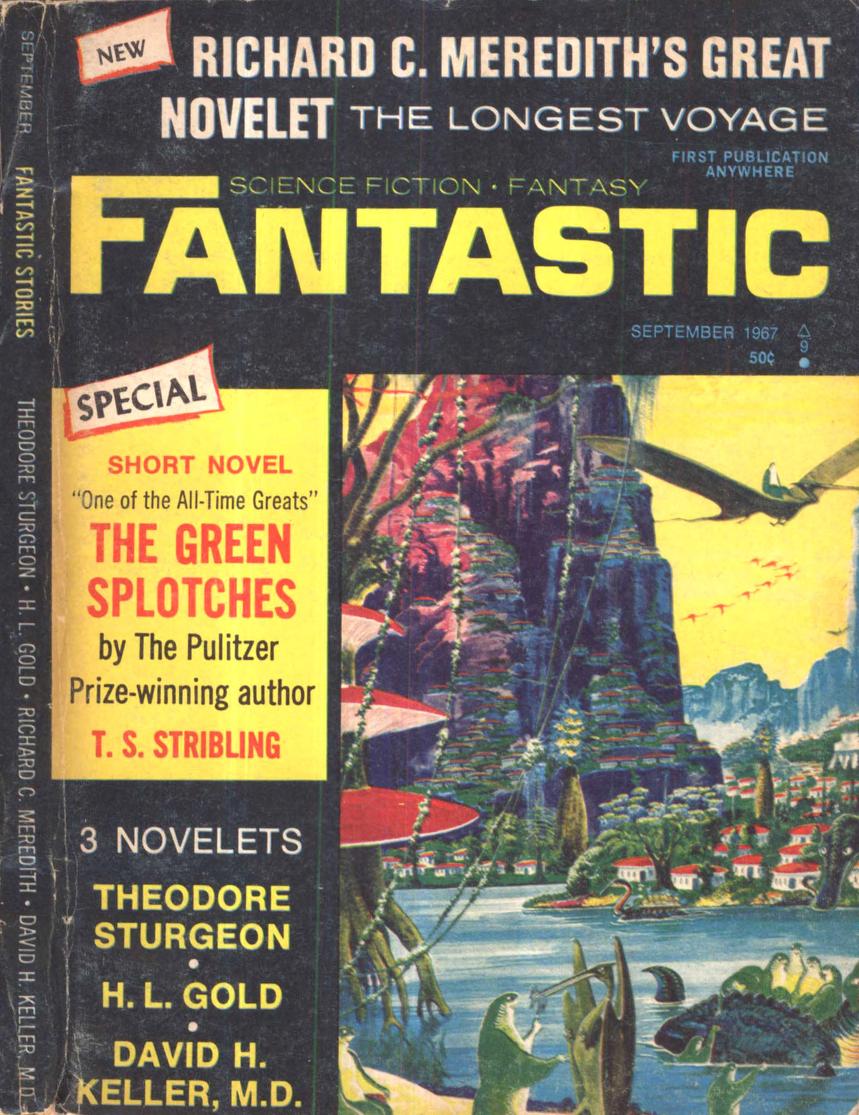

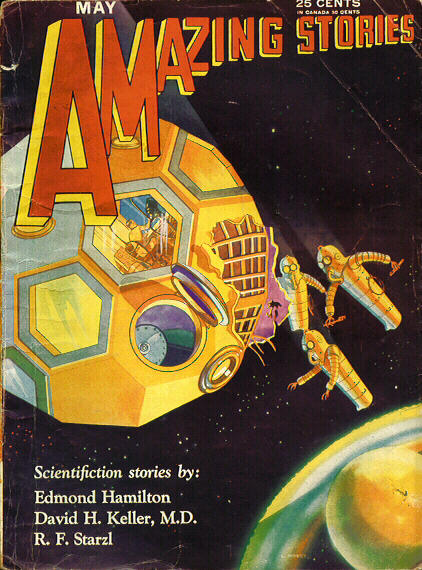

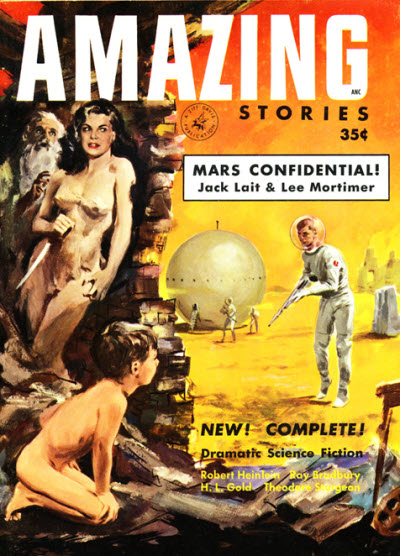

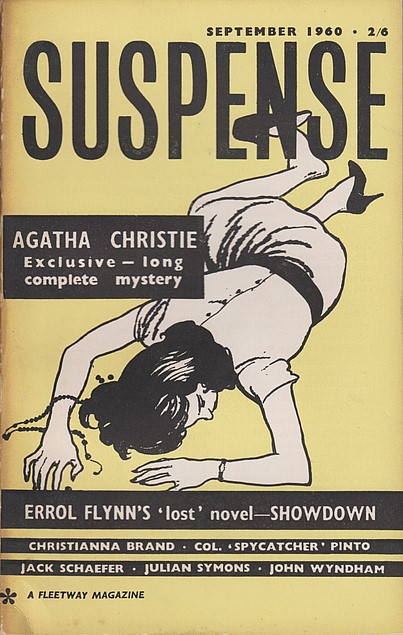

Cover art by Frank R. Paul.

As usual, the image on the front is taken from an old magazine. In this case, it's the back cover of the January 1941 issue of Amazing Stories.

The reprinted version omits the pink flamingo in the bottom right corner.

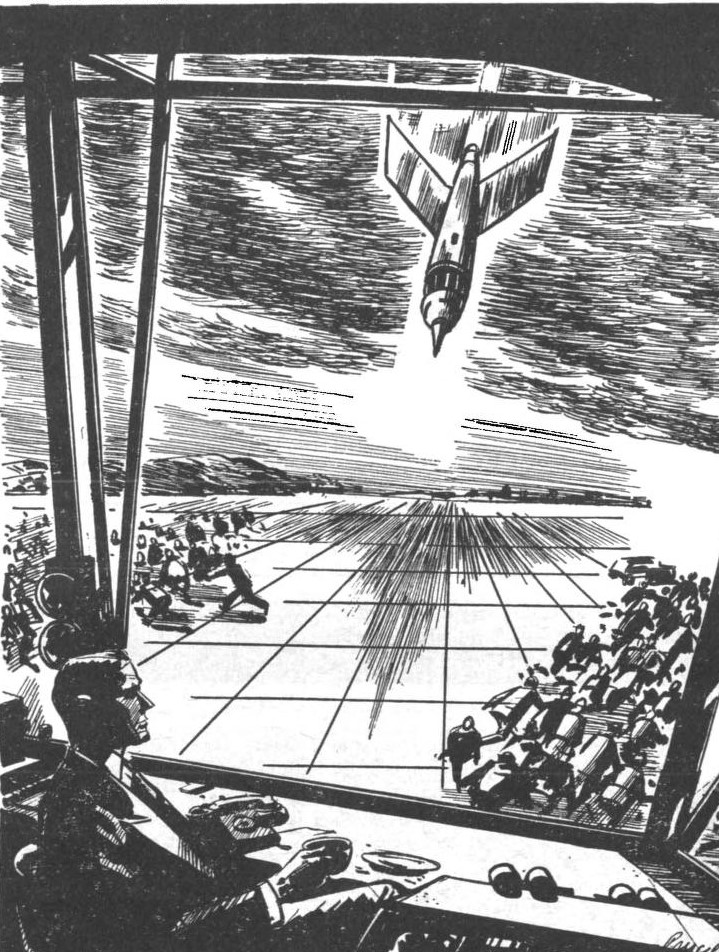

The Longest Voyage, by Richard C. Meredith

Illustrations by Gray Morrow.

Three spaceships carry the first astronauts to Jupiter. Incredibly bad luck strikes the mission. Freak accidents destroy two of the vessels and badly damage the third, leaving only one person alive. Seriously injured, the fellow faces a slow and lonely death.

It seems the crippled ship is now in orbit around Jupiter. The sole survivor has enough food, water, and air to last many years, but no way to contact Earth. (As I've indicated above, he's as far out of range as I am with KMPX.) Can our intrepid hero find a way to make his way back?

He also grows a beard.

This technological problem-solving story would be right at home in the pages of Analog. The protagonist makes use of some basic science and a lot of tinkering to overcome a seemingly impossible dilemma.

It's pretty well written for this kind of thing. The author really made me feel the character's suffering and desperation. I'm not sure I believe that a future society advanced enough to send spaceships to the far reaches of the solar system wouldn't figure out a way to talk to them. Without that plot point, the story would boil down to the hero sending out an SOS and waiting for rescue.

Three stars.

Same Autumn in a Different Park, by Peter Tate

Illustration also by Gray Morrow; he seems to be the only artist doing new work for the magazine.

Remarkably, this issue actually has two new stories. This one comes from a Welsh author usually seen in New Worlds. As you might expect, it has more than a little flavor of New Wave SF to it.

In another example of limited communication, a mother and father only talk to each other via teletype. In this grim future, the authorities have decided that the way to prevent violence is to have children raised apart from their parents. For that matter, the boy and girl in the story don't have any contact with anyone except each other and the machines that watch over them.

The devices give the children dolls representing the victims of nuclear war and a sample weapon, in an attempt to warn them about the horrors of violence. It's no surprise that this idea doesn't work out very well.

Typical of the New Wave, this story isn't as clear or linear as I may have made it sound. You have to read carefully and be patient to understand it. The premise is more effective as dark satire than as plausible speculation.

There's a strange scene in which the girl turns into a bird made from a hedge, through some kind of technological miracle. This weird transformation doesn't seem to have anything to do with the rest of the story, unless I'm missing something. It's a striking image, anyway.

This is an intriguing work, but one more to be admired than loved, I believe.

Three stars.

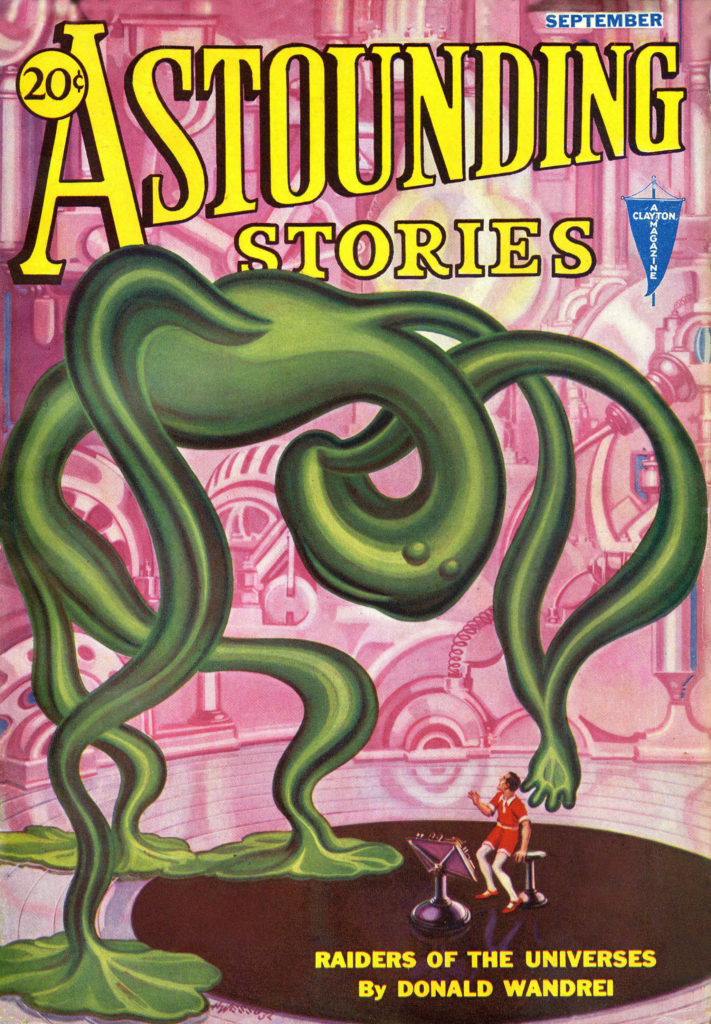

The Green Splotches, by T. S. Stribling

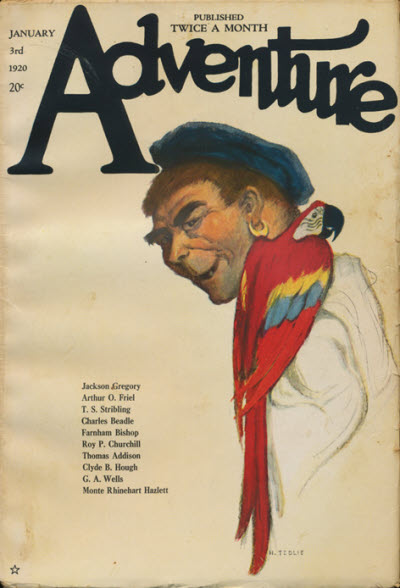

From the January 3, 1920 issue of Adventure comes this early example of interplanetary science fiction.

I'm guessing the cover artist's name is H. Tidlie, but maybe somebody with sharper eyes can make out the signature better than I can.

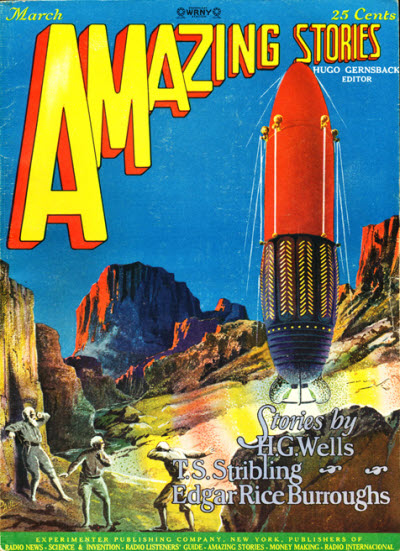

It was reprinted in the March 1927 issue of Amazing Stories.

Cover art by Frank R. Paul, of course.

The magazine is careful to tell me twice that Stribling went on to win a Pulitzer Prize after he lifted himself out of the pulps. For the record, it was for his 1932 work The Store, a novel about the southern United States after the time of Reconstruction.

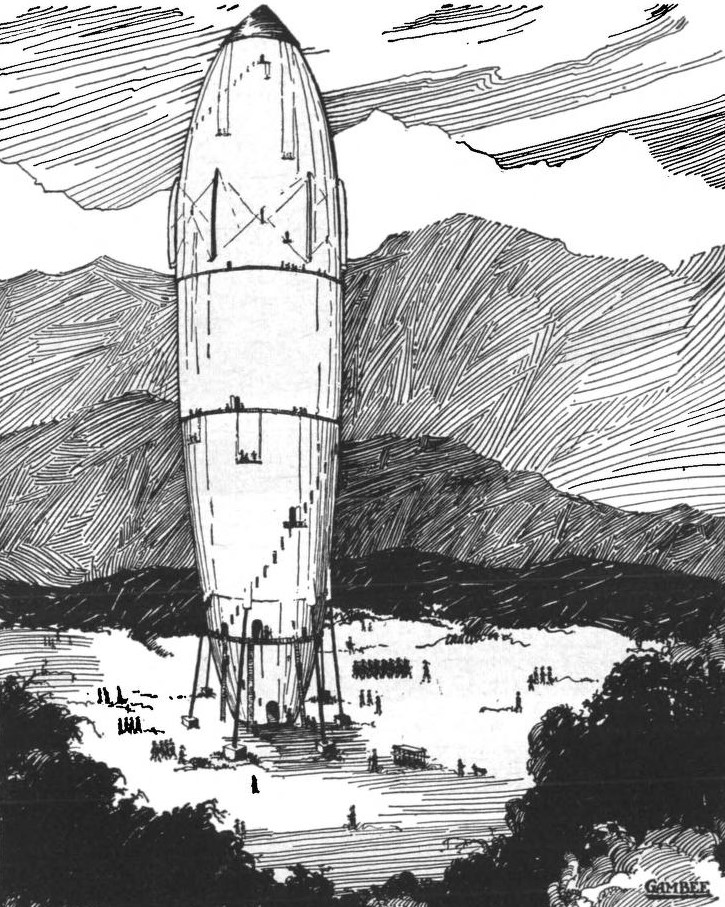

Illustration by somebody called Gambee, about whom I have no other information.

A scientific expedition heads for a remote area of Peru. The place has a very bad reputation. So much so, in fact, that the only locals willing to guide them there are two condemned criminals who would otherwise face execution.

The first eerie sign that something strange is going on comes when they find a series of carefully articulated skeletons of various animals, including a human being. Pretty soon, one of the two criminals shoots at and chases after somebody, disappearing in the process.

The others receive a visit from a strange person, who treats them as inferior beings. You'll figure things out, from the illustration if nothing else, although the human characters never do.

Although it's a little old-fashioned (this is one of those stories where radium is pretty much a synonym for magic), this is a very readable yarn. What most distinguishes it is a subtle note of satire. Although not comic, and sometimes even horrific, there's a sardonic tone throughout. There's a running joke, of sorts, about the expedition's reporter and his self-published book about reindeer.

Three stars.

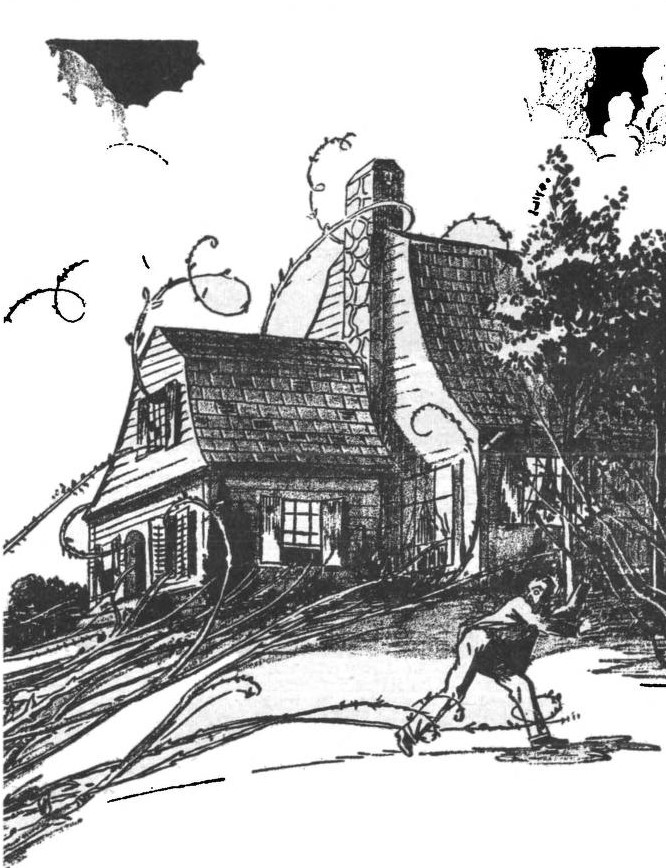

The Ivy War, by David H. Keller, M.D.

The May 1930 issue of Amazing Stories supplies this Kelleryarn.

Cover art by Leo Morey.

An aggressive, swift-moving, deadly form of ivy emerges from a pit and overwhelms a small town. Soon the seemingly intelligent plant invades larger cities, moving from place to place via water. Can anything stop it?

Illustration by Leo Morey also.

This reads like a science fiction monster movie of the last decade, with ivy taking the place of a giant bug or some such. It's even got one of those endings where Science discovers the only thing that will stop the menace. There's not much to it other than the premise. For what it is, it's adequate.

Three stars.

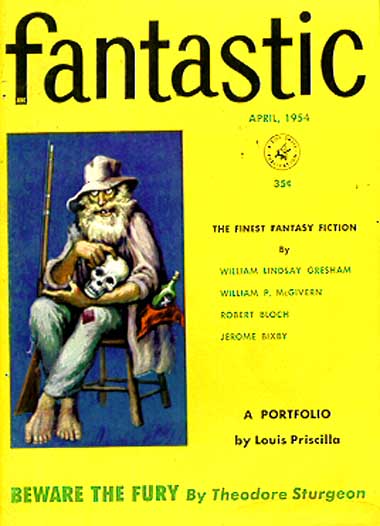

Beware the Fury, by Theodore Sturgeon

From the April 1954 issue of the magazine comes this work from one of the masters of imaginative fiction.

Cover art by Augusto Marin.

An astronaut seems to have betrayed Earth to invading aliens, making him the most hated human being in existence. A military type has the unenviable task of interviewing the traitor's wife, in an attempt to understand his actions. He learns of the man's unusual personality quirks, and of the couple's very strange marriage. With this knowledge, he tracks down the fellow when he returns to Earth and goes into hiding.

Illustration by Louis Priscilla.

I may have made this sound like a space war yarn, and there's certainly that aspect to the plot. However, the psychology of the characters is of much greater importance than the melodramatic aspects of the story. Sturgeon excels at this sort of thing, of course.

Four stars.

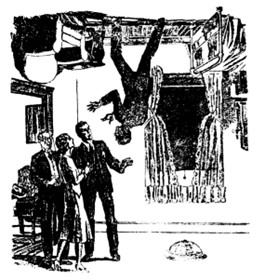

No Charge for Alterations, by H. L. Gold

The former editor of Galaxy offers this work from the April/May 1953 issue of Amazing Stories.

Cover art by Barye Phillips.

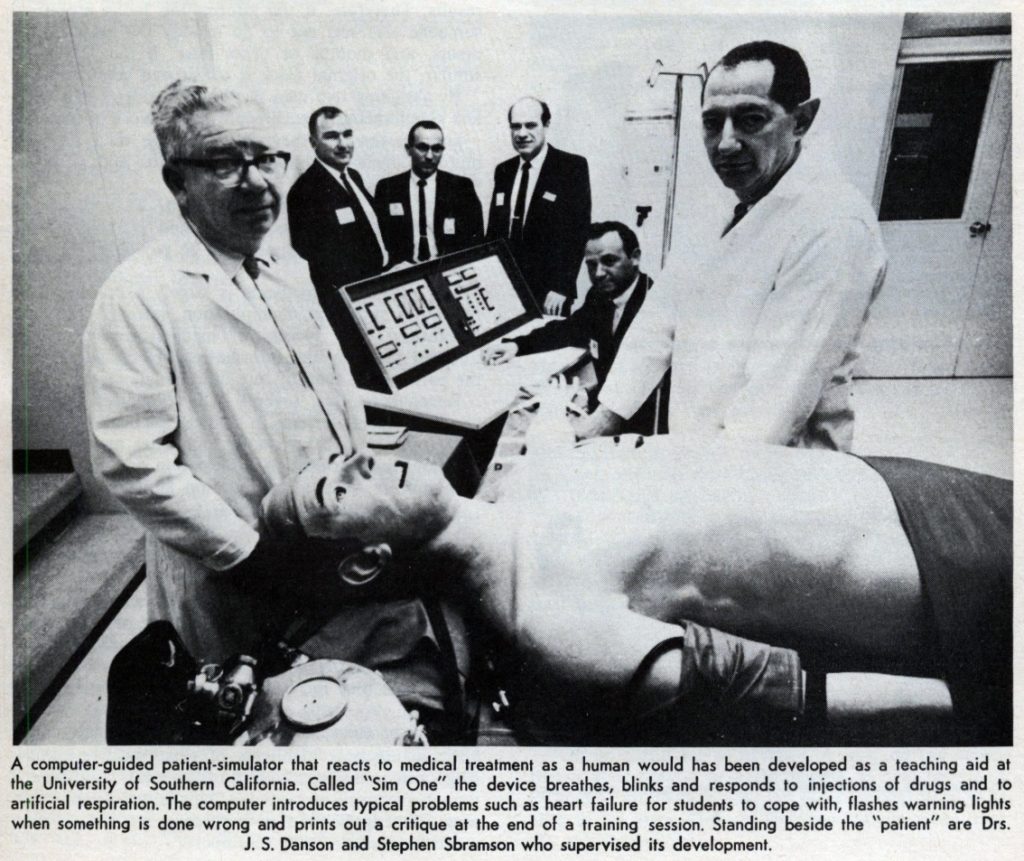

A doctor arrives on a colony world to study under a local physician. Medical technology exists that can change the patient not only physically, but mentally.

Interior illustrations by Henry Sharp.

He's shocked to see his mentor use the device to alter the mind of a young woman so she'll give up her dream of moving to Earth and becoming an entertainer, and instead be happy to do farm labor and raise children.

The After, in contrast to the above Before.

The new arrival decides to escape what he sees as an insane perversion of medicine and go back to Earth. The local doctor contacts the retired physician under whom he studied, in an attempt to keep the new guy from leaving. He learns something about his own time as a student.

I suppose this is supposed to be an ironic tale, maybe even humorous. I found the premise distasteful. The way in which the young woman at the start of the story is brainwashed to be a content farm wife is rationalized as being necessary to support the colony, but it gave me the creeps.

Two stars.

Signal to Noise Ratio

Well, that was a middle-of-the-road issue, rising above and sinking below average in a couple of places, but otherwise mediocre. It's notable not only for having two new stories, but for having only science fiction and no fantasy. The whole thing is like a radio station subject to bits of static now and then; worth tuning in for a while, but tempting you to turn the dial to something else. Something like a corny pun, that may amuse you for a while, but otherwise forgettable.

Like this one, from the same issue as the Sturgeon story, by somebody known only as Frosty.

Still, while I may not be able to tune in to KMPX, I can at least turn the dial to the similarly formatted KGJ. That's some comfort!

![[August 8, 1967] Distant Signals (September 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Fantastic_v17n01_1967-09_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

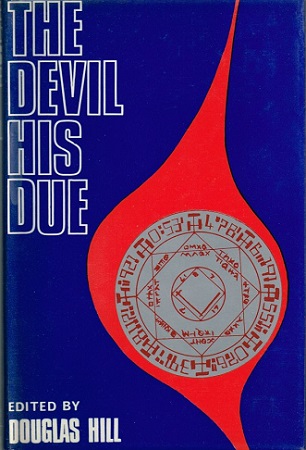

![[August 6, 1967] A Dark Future (<i>The Devil His Due</i> by Douglas Hill)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Devil-His-Due-2-306x372.jpg)

![[August 4, 1967] Bond Movie. James Bond Movie (<i>Casino Royale</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670427casinoroyale-672x372.jpg)

In plot terms, Casino Royale is two almost entirely separate films, tenuously linked by a handful of scenes. The ‘first’ plot features David Niven as a retired, now celibate, British agent named James Bond, who is returned to service when all other agents are being killed off due to their fondness for sex. Bond recruits a new agent, Coop (Terence Cooper), and instigates an anti-sex training programme, thus allowing the movie to have its cake and eat it through sequences of Coop being sexually tempted but boldly resisting. Mata Bond (Bond’s daughter by Mata Hari) is recruited by her father and discovers a plot to auction SMERSH agent Le Chiffre’s collection of blackmail materials to various military forces from across the world, whose senior staff have been photographed in compromising situations.

In plot terms, Casino Royale is two almost entirely separate films, tenuously linked by a handful of scenes. The ‘first’ plot features David Niven as a retired, now celibate, British agent named James Bond, who is returned to service when all other agents are being killed off due to their fondness for sex. Bond recruits a new agent, Coop (Terence Cooper), and instigates an anti-sex training programme, thus allowing the movie to have its cake and eat it through sequences of Coop being sexually tempted but boldly resisting. Mata Bond (Bond’s daughter by Mata Hari) is recruited by her father and discovers a plot to auction SMERSH agent Le Chiffre’s collection of blackmail materials to various military forces from across the world, whose senior staff have been photographed in compromising situations. Meanwhile Mata and Bond travel to Casino Royale, where they discover the mastermind behind SMERSH, Doctor Noah, is in fact Jimmy Bond, Bond’s nephew (Woody Allen), who has become a supervillain through feelings of inadequacy. Noah is tricked into swallowing a pill that turns him into a walking atomic bomb and a free-for-all breaks out in the casino, with invasions by cowboys, Indians, seals, the Keystone Kops, a French legionnaire, and actor George Raft — the whole thing eventually blowing sky-high as the heroes fail to prevent Noah from exploding.

Meanwhile Mata and Bond travel to Casino Royale, where they discover the mastermind behind SMERSH, Doctor Noah, is in fact Jimmy Bond, Bond’s nephew (Woody Allen), who has become a supervillain through feelings of inadequacy. Noah is tricked into swallowing a pill that turns him into a walking atomic bomb and a free-for-all breaks out in the casino, with invasions by cowboys, Indians, seals, the Keystone Kops, a French legionnaire, and actor George Raft — the whole thing eventually blowing sky-high as the heroes fail to prevent Noah from exploding. Certain elements of the story are indeed more or less direct spoofs, either of the James Bond franchise itself or of the wider spy series craze. The film starts with a pre-credits sequence which is just a tiny scene of Bond meeting a French agent in a pissoir, simultaneously setting up and destroying expectations of a James Bond-style pre-credits action sequence. Mata Bond’s trip to Germany places her within a stage set straight out of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, in a nod to the huge debt the spy film genre owes to Expressionist artform. The supporting cast includes people who’ve either appeared in Bond movies or the many independent television spy series that have cashed in on the Bond craze, notably Ursula Andress but also Vladek Sheybal and promising young character actor Burt Kwouk. As in many spy series, doubles and duplicates turn up frequently. The bizarre conceit of having all the agents, male, female, and, by the end of the adventure, animals, named James Bond/007, can be construed as a sly comment on the fact more than one actor has played Bond, or even a metatextual joke about the proliferation of code-names and numbers in such series. And, of course, the villain is motivated by a sense of personal and sexual inadequacy—what spy series villain isn’t?

Certain elements of the story are indeed more or less direct spoofs, either of the James Bond franchise itself or of the wider spy series craze. The film starts with a pre-credits sequence which is just a tiny scene of Bond meeting a French agent in a pissoir, simultaneously setting up and destroying expectations of a James Bond-style pre-credits action sequence. Mata Bond’s trip to Germany places her within a stage set straight out of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, in a nod to the huge debt the spy film genre owes to Expressionist artform. The supporting cast includes people who’ve either appeared in Bond movies or the many independent television spy series that have cashed in on the Bond craze, notably Ursula Andress but also Vladek Sheybal and promising young character actor Burt Kwouk. As in many spy series, doubles and duplicates turn up frequently. The bizarre conceit of having all the agents, male, female, and, by the end of the adventure, animals, named James Bond/007, can be construed as a sly comment on the fact more than one actor has played Bond, or even a metatextual joke about the proliferation of code-names and numbers in such series. And, of course, the villain is motivated by a sense of personal and sexual inadequacy—what spy series villain isn’t? However, both plots reach their highest, as well as their lowest, moments when they embrace the surreal comedy ethos. Arguably this started with The Goon Show, of which Sellers was a key member, before really finding its home with audiences in the Sixties. Current examples of this genre include What’s New, Pussycat?, Round The Horne, the Dadaist stylings of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and At Last the 1948 Show. The trend is gaining strength: reportedly Paul McCartney is also a fan and is keen to adopt fantastical elements into Beatles films. So it’s not surprising, given the involvement of Sellers and Feldman, that Casino Royale would be taken in such a direction.

However, both plots reach their highest, as well as their lowest, moments when they embrace the surreal comedy ethos. Arguably this started with The Goon Show, of which Sellers was a key member, before really finding its home with audiences in the Sixties. Current examples of this genre include What’s New, Pussycat?, Round The Horne, the Dadaist stylings of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and At Last the 1948 Show. The trend is gaining strength: reportedly Paul McCartney is also a fan and is keen to adopt fantastical elements into Beatles films. So it’s not surprising, given the involvement of Sellers and Feldman, that Casino Royale would be taken in such a direction. The picture’s surreal comedy doesn’t always work. For instance, there’s an annoyingly self-indulgent sequence which seems just an excuse for Sellers to dress up as historical characters. Others are better: Niven’s Bond, for instance, lives on an estate guarded by a pride of lions (“I did not come here to be devoured by symbols of monarchy!” protests the Soviet head of espionage), and the idea James Bond and Mata Hari had a relationship is a somehow appropriate melding of the archetypes of the male and female spy. Mata Bond stops the auction of Le Chiffre’s compromising photos by switching the projector to a war film: as if triggered, the British, American, Chinese and Russian representatives instantly all start fighting each other, in a comment on the Cold War worthy of

The picture’s surreal comedy doesn’t always work. For instance, there’s an annoyingly self-indulgent sequence which seems just an excuse for Sellers to dress up as historical characters. Others are better: Niven’s Bond, for instance, lives on an estate guarded by a pride of lions (“I did not come here to be devoured by symbols of monarchy!” protests the Soviet head of espionage), and the idea James Bond and Mata Hari had a relationship is a somehow appropriate melding of the archetypes of the male and female spy. Mata Bond stops the auction of Le Chiffre’s compromising photos by switching the projector to a war film: as if triggered, the British, American, Chinese and Russian representatives instantly all start fighting each other, in a comment on the Cold War worthy of  Furthermore, the surrealist aspect transforms some of the problems and conflicts that arose during its production, from potential flaws to part of an overarching psychedelic atmosphere. Orson Welles had apparently insisted on performing magic tricks on camera, but these become both a send-up of the contrived “eccentricities” of spy-series villains and a deeper comment on illusion and artifice. The title sequence, which starts out as a simple riff on Bond films’ animated credits, becomes increasingly disconcerting, the imagery including walls of eyes staring pitilessly out at the viewer, with connotations of surveillance and voyeurism.

Furthermore, the surrealist aspect transforms some of the problems and conflicts that arose during its production, from potential flaws to part of an overarching psychedelic atmosphere. Orson Welles had apparently insisted on performing magic tricks on camera, but these become both a send-up of the contrived “eccentricities” of spy-series villains and a deeper comment on illusion and artifice. The title sequence, which starts out as a simple riff on Bond films’ animated credits, becomes increasingly disconcerting, the imagery including walls of eyes staring pitilessly out at the viewer, with connotations of surveillance and voyeurism. At the climax, the presence of multiple James Bonds escalates into a scenario where literally everyone becomes the titular hero; and this, together with the recurrence of doubles and duplicates, poses serious questions about how we construct our identity in modern society. At the end, everyone dies, going to Heaven or Hell, the accompanying random images and cheery music underscoring that there can be no guaranteed rescue or happy-ever-after in the atomic age.

At the climax, the presence of multiple James Bonds escalates into a scenario where literally everyone becomes the titular hero; and this, together with the recurrence of doubles and duplicates, poses serious questions about how we construct our identity in modern society. At the end, everyone dies, going to Heaven or Hell, the accompanying random images and cheery music underscoring that there can be no guaranteed rescue or happy-ever-after in the atomic age.![[August 2, 1967] The Bounds of Good Taste (September 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/IF-Cover-1967-09-672x372.jpg)

President de Gaulle with foot firmly in mouth.

President de Gaulle with foot firmly in mouth. This alien dude ranch has become a popular honeymoon spot. Art by Gray Morrow

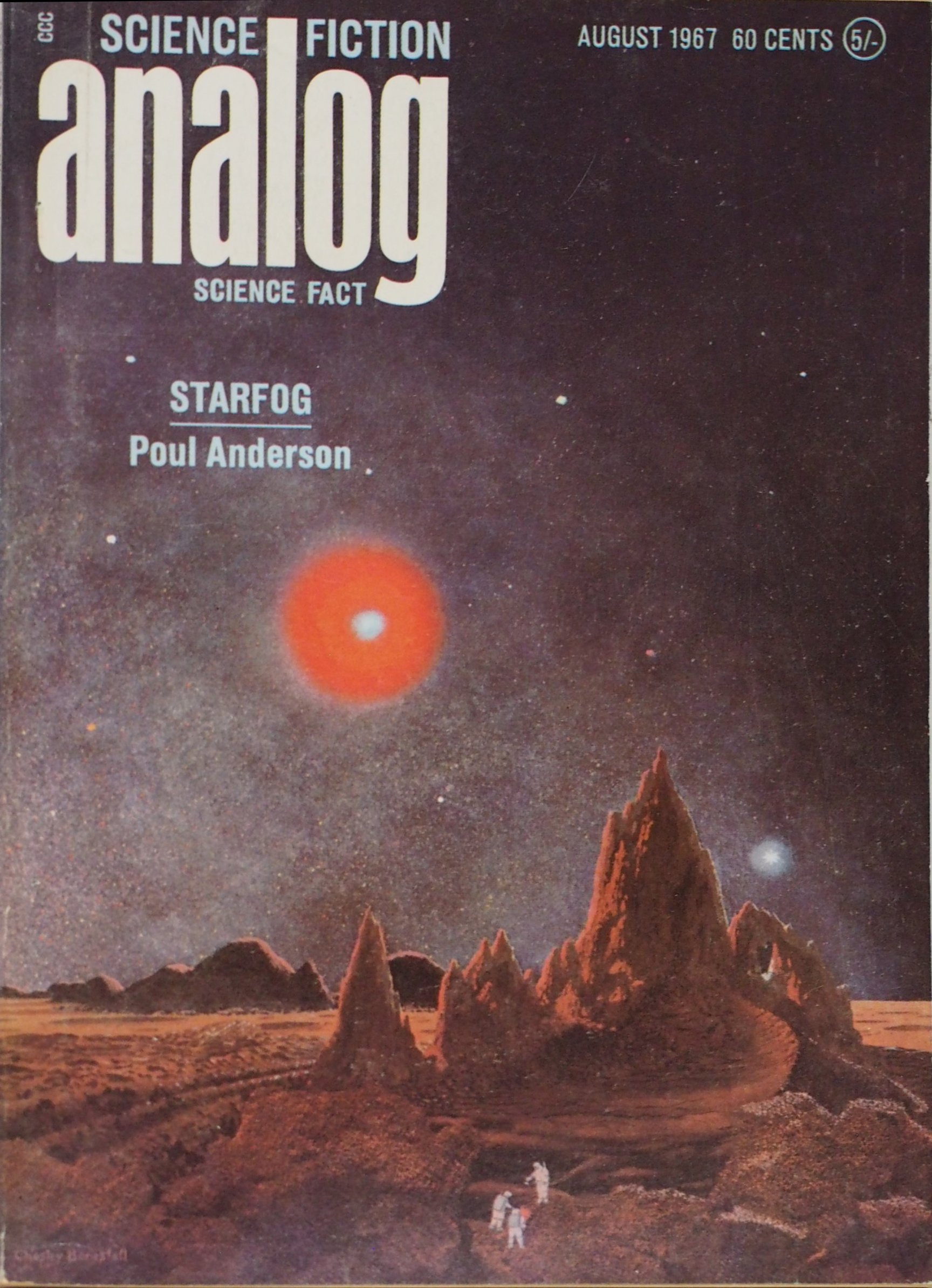

This alien dude ranch has become a popular honeymoon spot. Art by Gray Morrow![[July 31, 1967] Canceling waves (August 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670731cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 28, 1967] The Shock of the New – Rabbits, Hedgehogs and Kazoos (<i>New Worlds</i>, August 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/NW-September-1967-672x372.jpg)

![[July 24, 1967] Not Feelin’ Groovy (<i>Famous Science Fiction</i> #1-3)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Famous-Cover-Image.jpg)

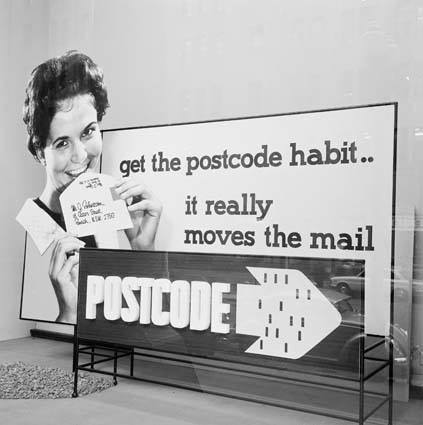

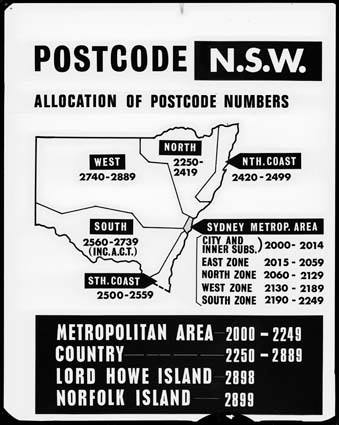

![[July 22, 1967] Getting the mail through (Australia introduces Postcodes)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Postcode-3-423x372.jpg)

![[July 20, 1967] An Analog of <i>Analog</i> (August 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670720cover-659x372.jpg)