by Gideon Marcus

The Good Doctor

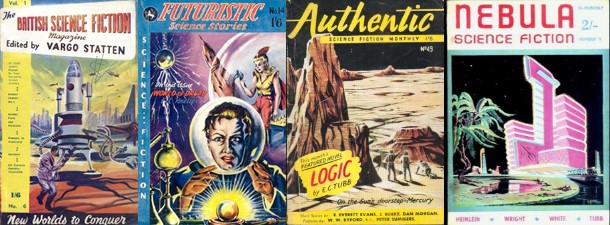

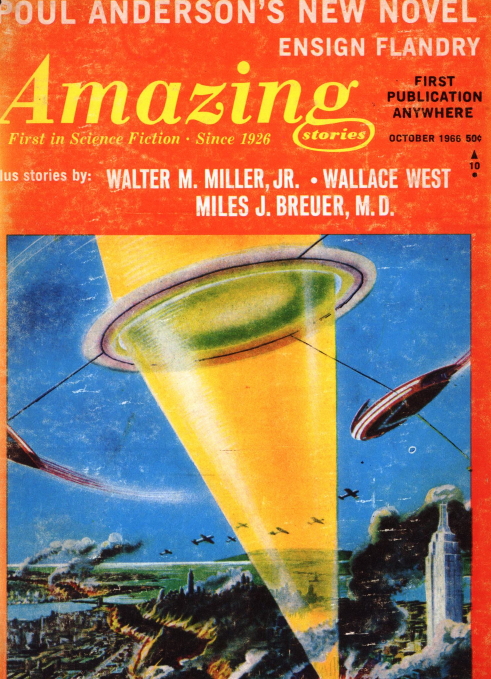

If generations are measured in 20 year spans, then science fiction is entering its third generation. It all started with Weird Tales, Amazing Stories, and the other more speculative pulps of the mid 1920s. By the 40s, we were in what folks are calling the "Golden Age", when Astounding ruled the roost. Since then, we've had what I'd call the "Silver Age" (or perhaps the "Digest Age" or the "Galactic Age") and are just starting one called the "New Wave".

The pulp age is now so long ago that we've already lost some of its more prominent writers: Doc Smith passed away last year, Ray Cummings was gone by 1957, Robert Howard and H.P. Lovecraft didn't make it out of the 1930s. Others are still alive and well…and still active: Murray Leinster, Jack Williamson, Edmond Hamilton, Clifford Simak, Frank Bellknap Long, Hugo Gernsback.

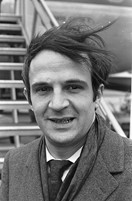

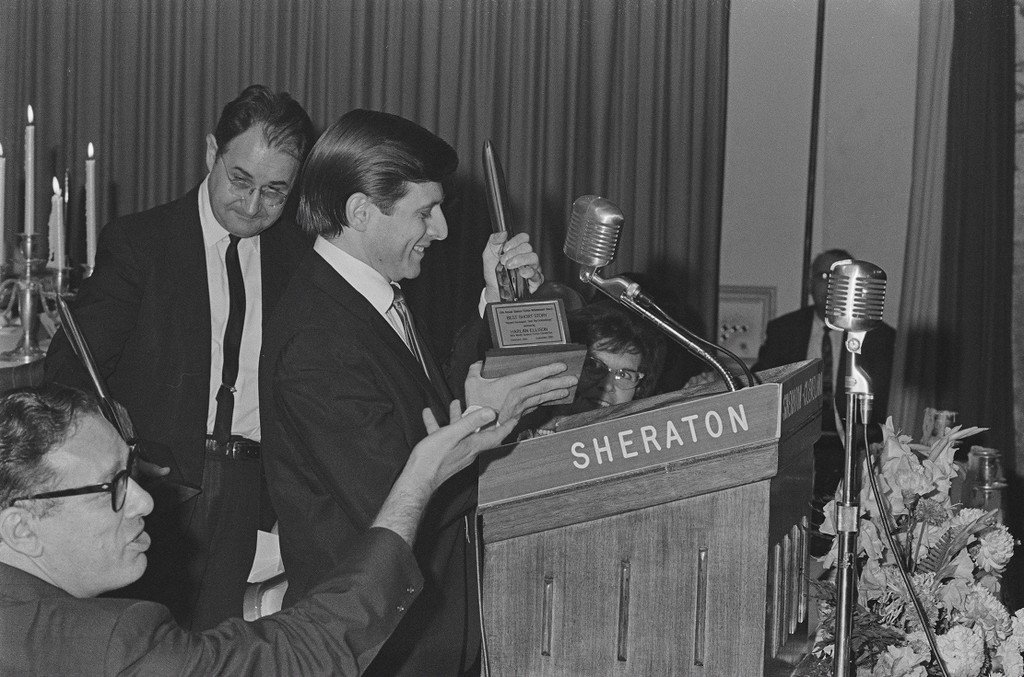

The Golden Age spawned a new crop of greats, from Leigh Brackett to John W. Campbell, jr. And there may be no author of that era of bigger stature, greater prolificity, not to mention bottom line, than Isaac Asimov.

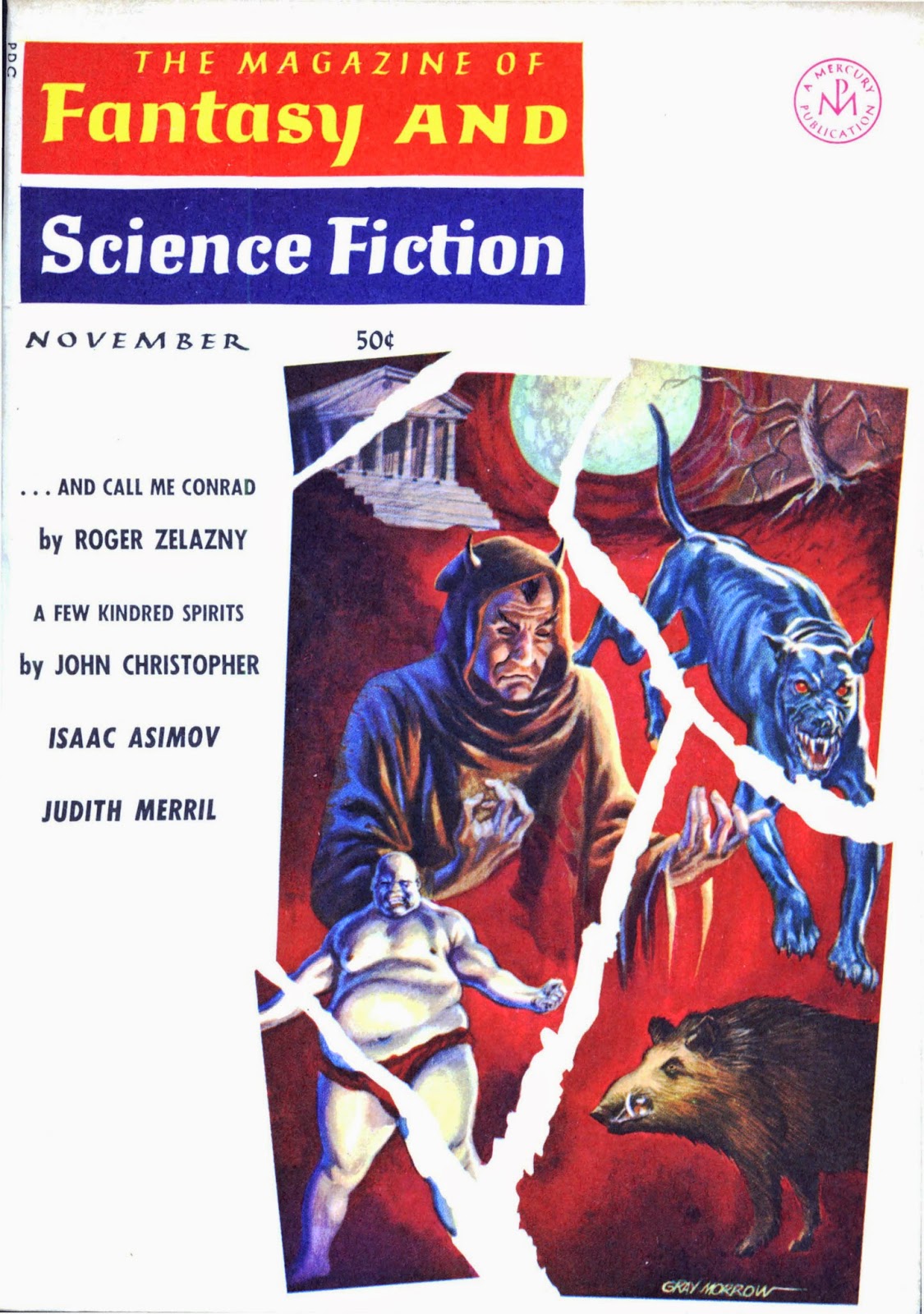

One can say a lot about Isaac. Garrulous, idiosyncratic, a workaholic, too pushy with his "harmless" romantic advances. But also brilliant, thoughtful, charming (at least in print). Love him or hate him, there's no question that he's left his mark on the field — from Nightfall, to I, Robot, to Foundation. For twenty years, Asimov turned out SF stories with incredible reliability. Then, with the launch of Sputnik, he turned his pen mostly to science fact. He's found a permanent home at The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, to that publication's credit. Asimov also churns out a flood of science books for the mass market. There's really no category of the Dewey Decimal System this fellow hasn't touched upon. He's an inspiration (a cautionary tale?) to us all.

So it was perhaps inevitable that F&SF would devote an issue to this titan of the genre. If you can get past the over-the-top cover — but it's nice to see EMSH back — then a decent mag awaits. Especially at 50 cents, which is cheap these days for a digest.

The Man Behind the Curtain

by Ed Emshwiller

The Key, by Isaac Asimov

First up is Asimov's first new SF story of significant length in quite some time. Two geologists stumble upon an alien artifact during a selenological expedition. Its ramifications for humanity are profound, so much so that the two have a lethal brawl. One escapes to hide the artifact before dying.

He leaves this clue:

It's up to Wendell Urth, the agoraphobe protagonist of several F&SF stories from the mid 1950s, to crack the case.

The beginning is pretty gripping, and I'm happy to say I got some of the clues. But it boils down to a rather abstruse puzzle with a bit too much punning for my taste.

Three stars.

You Can't Beat Brains, by L. Sprague de Camp

Sprague's short bio of his friend, Isaac, is not entirely flattering, but it does spotlight Asimov's undoubtedly prodigious intellect.

Three stars.

Isaac Asimov: A Bibliography, by Isaac Asimov

If you ever wanted to know what Asimov has been up to (besides chasing skirts) for the last thirty years, this is a good ledger. 25 science fiction books (two of which the Journey has covered), three pages of short stories, three more pages of non-fiction articles (most of which the Journey has covered), and 30+ nonfiction books.

Whereas I've got just two books and four stories (and a thousand non-fiction articles) to my credit. Ah well. I'm still young.

Portrait of the Writer as a Boy, by Isaac Asimov

For this month's non-fiction article, Asimov takes on his favorite subject — himself! Actually, I appreciated this glimpse into the world of science fiction reading and writing in the late 30s. It's an era I missed, despite having been born just a few months before Asimov (not having gotten into STF in a big way until ~1950). Perhaps he'll some day use this article as a nucleus for an autobiography. He's written everything else.

Four stars.

The Prime of Life, by Isaac Asimov

Here's a mildly diverting poem about being a legend in his own time, but too young yet to be taken seriously.

Three stars.

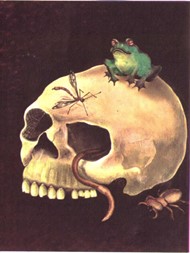

by Gahan Wilson

The Mirror, by Arthur Porges

You didn't think it was going to be all about Asimov, did you? Sure, he did, but you?

Mr. Porges offers up a paint-by-numbers piece of macabre about an old mansion with a spooky looking glass over the mantle. The setup and the telling were quite good, but the ending was second-tier early days FSF — or maybe even earlier pulp.

Three stars.

Come Back Elena, by Vic Chapman

The science fictional notion of storing memories in a computer and then inserting them into an android or biological blank slate has been around a while. This latest take from a new author starts quite promisingly. A grieving husband finds his wife's doppleganger a decade after the wife's death. She agrees to contribute sufficient biological material such that he can quick grow a new body as a vessel for her stored memories. But, of course, All Does Not Go Well.

There's a novel's worth of premise to explore here: is it murder to displace the personality of a human being, even one that has been alive for just a few days? Is the resulting person a new persona or a ressurrection of the old? What are the legal ramifications, for the subject and the experimenter?

Chapman avoids all of these, instead turning in a rather humdrum "shock" ending. It's a pity because the first half is quite strong.

Three stars.

Something in It, by Robert Louis Stevenson

Vignette on the immovable faith of a missionary encountering the irresistible force of an indigene's religion.

Blink and you'll miss it. Three stars.

The Picture Window, by Jon DeCles

"There's nothing new under the Sun." So complains an industrialist to his artist friend. Or should I say "former" friend as the dam the capitalist has erected is flooding out the beloved valley the painter has made his home. The artist bets his ex-buddy $50,000 that he can make a truly new piece of art.

What he creates is…well, you be the judge.

Jon (he's a friend, so I call him Jon, even though that's not his actual name) has created a story that is, in execution, something of the opposite to Chapman's and Porges'. It starts out a bit rocky, all shouty dialogue, but the latter half is memorable.

I'll take a good ending over a good beginning. Four stars.

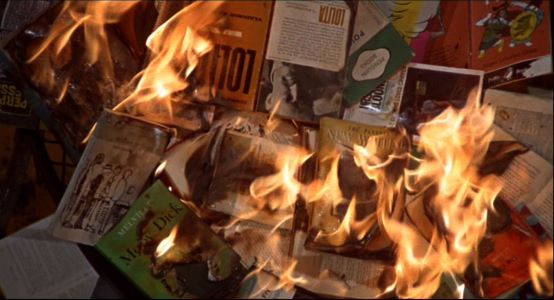

Burning Question, by Brian W. Aldiss

Speaking of memorable, here's a story snatched right from the front page. An inhabited world far from Earth is soon to be a way station to the stars in a galactic continuation of the Cold War. The indigenes have decided they would rather immolate themselves in protest than tolerate our base. One sympathetic colonel's attempts to sway the American authorities to give in to native demands just this once fall on deaf ears.

There's some good philosophical stuff in here, and maybe some lessons for Lyndon. Four stars.

An Extraordinary Child, by Sally Daniell

Lastly, a piece by another newcomer. This one involves a child with a handicap of the mind. He is brilliant, but tuned to another wavelength — one that allows him to see the little people. Only these brownies/faeries/elves all speak like Beatniks, and they have murder on their mind.

Our Esteemed Editor has noted that woman authors are far more likely to have children featured in their stories. I had high hopes for this one, a well-written piece portraying a sympathetic child with a mental aberration. Unfortunately, it settles for cheap thrills rather than profound statements.

Three stars. Maybe next time.

What's Up, Doc?

All told, this Asimovian issue is not one for the ages. Part of the problem is the two newcomers are not stellar, and Asimov is a bit rusty. That leaves just a couple of veterans to contribute comparatively good stories, and an old grognard to turn in…a typically unimpressive piece.

Perhaps Isaac deserves better than this. Or perhaps, like a revue show featuring an over-the-hill performer, it's exactly what one would expect.

![[September 22, 1966] True Idols (the Isaac Asimov issue of <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660920cover-659x372.jpg)

![[September 20, 1966] In the hands of an adolescent (<i>Star Trek</i>'s "Charlie X")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660920a-672x372.jpg)

![[September 18, 1966] Soaring Higher (Gemini 11)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Gemini-11patch-2-308x372.jpg)

![[September 16, 1966] Is Censorship Heating Up? (Fahrenheit 451)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/F451-Poster.jpg)

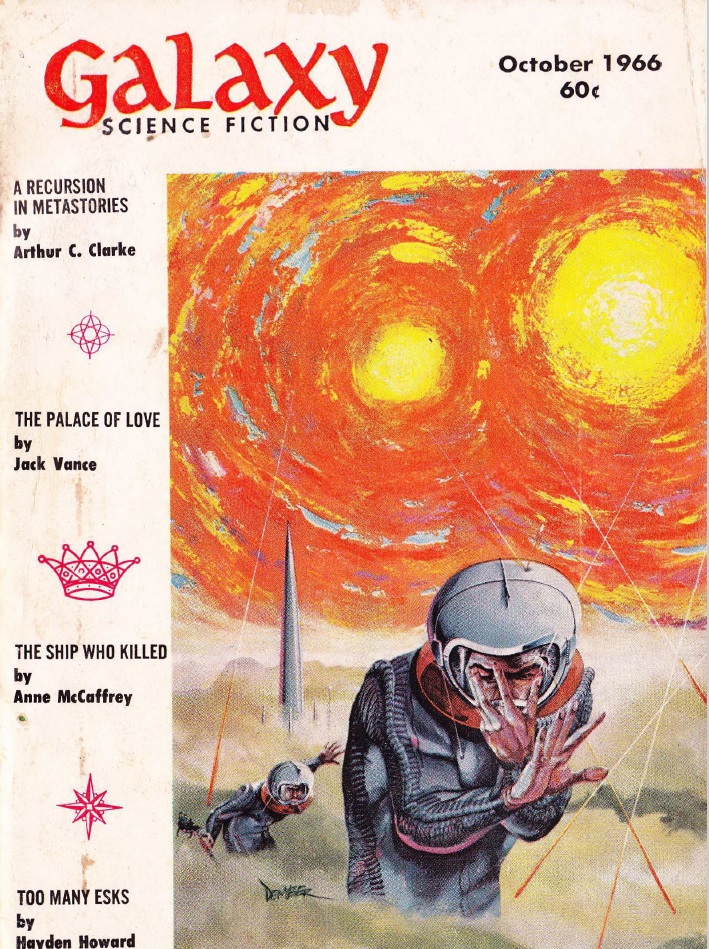

![[September 14, 1966] All the Old Familiar Places (October 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660912cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 12, 1966] Boldly Going (<i>Star Trek</i>'s "The Man Trap")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660914title-672x372.jpg)

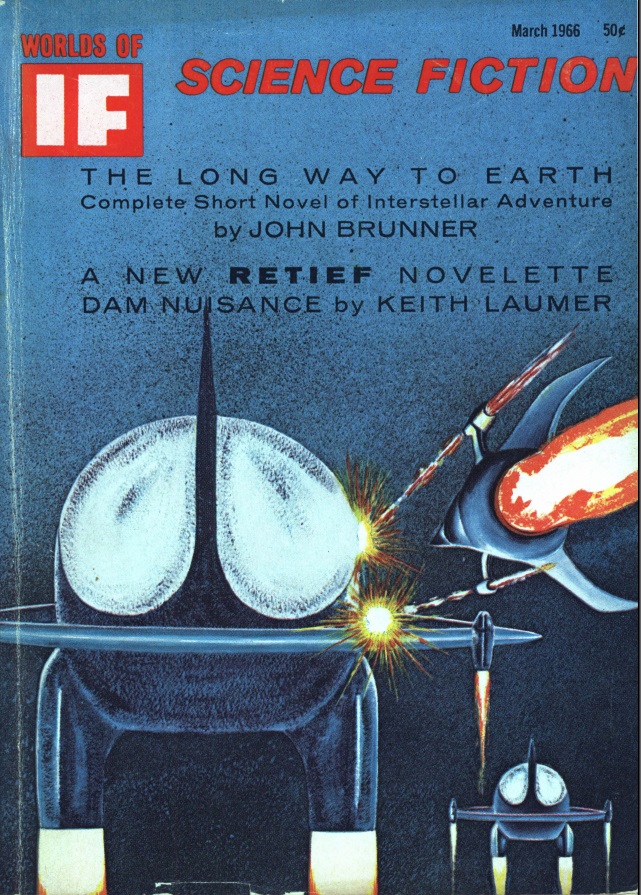

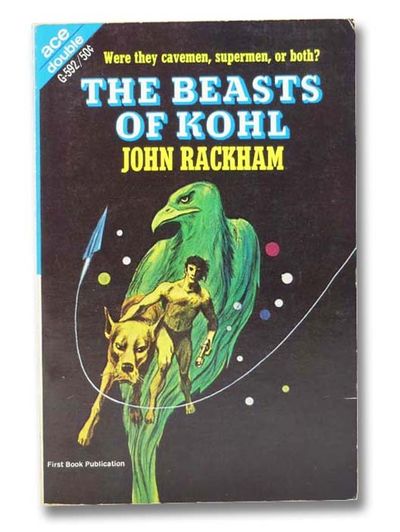

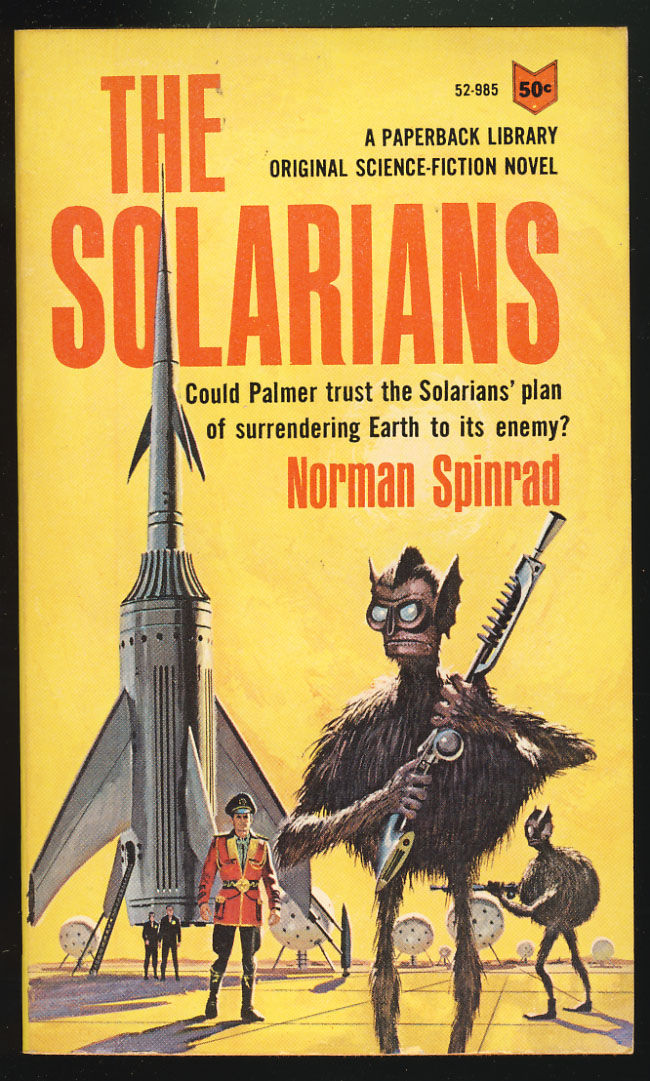

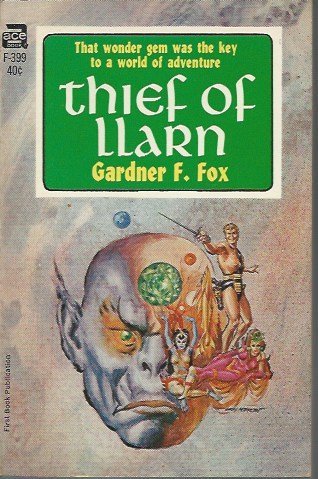

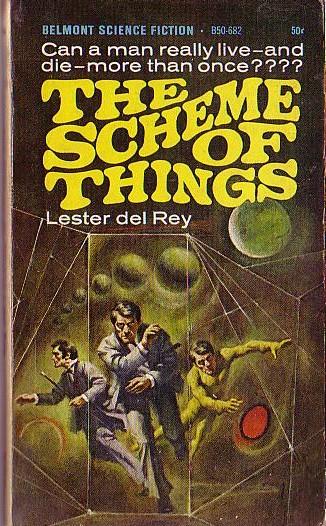

![[September 10, 1966] Bon appetit! (this month's Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/660910covers-672x372.jpg)

![[September 8, 1966] The Bare Hardly-Essentials (October 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)</big></b>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/amz-1066-cover-491x372.png)

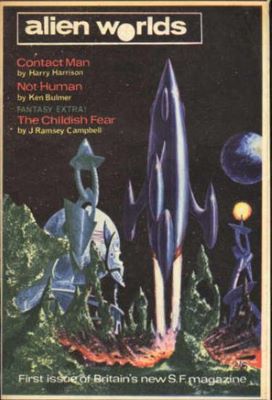

![[September 4, 1966] British Science Fiction Lives! (Alien Worlds #1 & New Writings in SF #9)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Featured-Image.jpg)