by Kaye Dee

I wasn’t contributing to the Journey last year, when Australia’s first home-grown science fiction television show, the children's series The Stranger, premiered in April 1964. So before the second series screens later this year, I thought I would take the opportunity to talk about this milestone in Australian television.

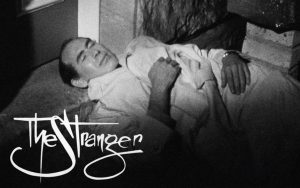

The screen title for The Stranger, with its unique, otherworldly script

Introducing G.K. Saunders

The Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) is the first local producer to show an interest in making science fiction for television, adapting The Stranger from a radio serial by prolific radio and television script writer Mr. G. K. "Ken" Saunders. A British-born New Zealander who moved to Australia in 1939, Mr. Saunders began writing scripts for ABC radio children’s programmes as well as radio dramas for one of the commercial networks.

During the War, Mr. Saunders also worked for the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). His exposure to scientific research seems to have sparked an interest in science fiction, because when he returned to writing scripts for ABC radio children’s programming, he produced about a dozen serials with science fiction themes. Mr. Saunders has said that he bases his science fiction on real science, and he consulted scientists from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO, the successor to the CSIR) to ensure this. But his stories also have a bit of a twist to them, and both these traits can be seen in The Stranger.

Recording an episode of the Argonauts Club, a popular children's radio programme that has been on air since 1941. Ken Saunders is best known as one of its main script writers since it began

Some of the science fiction serials Mr. Saunders wrote still stick in my mind. His first, The Moon Flower, was broadcast in 1953. It tells the story of the first expedition to the Moon, which discovers a tiny flower in a deep cave. This might seem a bit silly today, with what we now know about the Moon from Ranger 9 and other lunar probes, but back then some scientists still thought there might be simple life on the Moon. There was another one I really liked, in which the first expedition to Alpha Centauri discovers a planet inhabited by a human-like species who are pretty much like us – except they never invented music! I found this a fascinating idea.

The Genesis of The Stranger

Ken Saunders moved to England in 1957, working as a television and radio script writer for the BBC. This is where the story of The Stranger really begins: it was originally written as a six-part radio play for the BBC, which was broadcast in 1963, so perhaps some British readers of this article might even have heard it. From what my friend at the ABC has told me, it seems that the first series of the Australian television version is very similar to the original radio play storyline, with the six 30 minute television episodes drawn from the six parts of the radio serial.

Playing possum. A publicity still showing a scene from the opening teaser, where the stranger pretends to be unconscious at the door of Headmaster Walsh's house

Episode 1

Broadcast on 5 April 1964, the first episode of The Stranger begins with a short teaser: on a classic dark and stormy night, a figure makes its way along a dark street to the gate of a house. A signboard on the fence tells us this is the home of the Headmaster of St Michael’s School for Boys. This stranger walks to the door and lies down, carefully arranging himself to look like he has collapsed. He then taps weakly on the door and closes his eyes pretending he is unconscious. This is followed by the opening credits that are used for the rest of the series: the CSIRO’s Parkes Radio Telescope scans the skies in a timelapse sequence that then dissolves into a cosmic view of stars and nebulae against which the title The Stranger appears, written in an unusual, fantastical script. The author’s credit and episode number then appear over a slow pan of what seems to be a desolate, crater-pocked landscape. These images and the eerie, slightly foreboding theme music, set the scene for the mystery that follows and unfolds over the six episodes.

Headmaster Walsh and his family help the apparently sick stranger on their doorstep, who claims to have lost his memory but speaks with a European accent. When they discover that he speaks French and German there is speculation that perhaps he is Swiss. The rapidly recovering stranger declares that because he cannot recall his own name, he will give himself another: Adam, since he is a ‘new man’, and Suisse, since he is possibly Swiss.

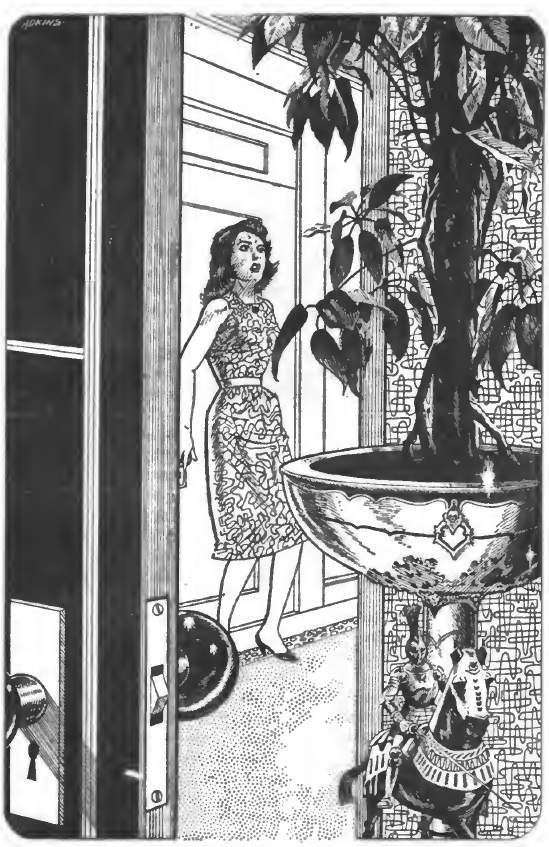

What's in a name? The amnesiac stranger, who has christened himself Adam Suisse, with his hidden radio that sparks the suspicions of our three teenage heroes

Events then move quickly: Adam becomes a language teacher at St. Michael’s and takes up residence in a disused building on the school grounds. There, at the end of Episode 1, the teenage Walsh children, Bernie and Jean, and their friend Peter, accidentally discover a strange radio-like device, hidden under a loose floorboard. Turning it on, they hear speech in a foreign language.

Episode 2

The teenagers suspect that Adam is a spy. Although he attempts to allay their suspicions, Peter is not convinced, and they follow Adam on one of his weekend bushwalks in the Blue Mountains. Adam has spoken passionately about his love for walking in the bushland and being close to nature but disparages reports about flying saucers seen in the area where he likes to hike. Bernie, Jean and Peter try to track Adam through the bush and at the end of the episode come face to face with a hidden flying saucer!

Not what you expect to find on a bushwalk! The "flying saucer" piloted by Adam's friend Varossa, hidden away in the Blue Mountains

Episode 3

Adam takes the three teenagers onboard the flying saucer, revealing that he represents about 300 survivors living inside a colony ship created from a small planetary moon. Known as Soshuniss, the moon-ship has been travelling for generations since the planet from which its people originally came was poisoned and made unlivable by some kind of “accident”. The Soshunites seek a new home and have been reconnoitring the Earth. They would like to live here, but have no intention of invading, as they are a peaceful people. Back on Earth, the teenagers’ disappearance is treated by the police as an elaborate hoax, abetted by the missing Adam. When Adam and the teenagers arrive on Soshuniss, they are taken to an audience with the Soshun, the leader of the Soshunites.

Fly me to the moon! Adam reveals the truth about himself to Jean, Peter and Bernie, on board the spaceship travelling to the moon-ship Soshuniss

Episode 4

The surprised teenagers discover that the Soshun is a pleasant elderly woman. She asks them to deliver a letter to the Australian Prime Minister requesting permission for the Soshunites to settle in part of Australia. In return the Soshunites will share their scientific knowledge with the world. On returning to Earth with Adam and his friend Varossa, the young people’s story is disbelieved by their parents and the police. The Soshunites are arrested as kidnappers and spies, while visiting American scientist Prof. Mayer persuades the teenagers to prove their story by taking him secretly to the hidden spaceship they returned on. Although he is convinced of the truth of the story when he sees the spaceship, the police have been following them and Bernie attempts to take off with the others in the flying saucer to return it to the Soshunites.

Take me to your leader! Peter, Bernie, Prof. Mayer and Jean meet the Soshun, who can be seen in the background of this shot

Episode 5

Bernie is unable to properly control the spacecraft and the friends are rescued by another ship and taken to Soshuniss. The police who saw the flying saucer lift off contact the authorities and the spacecraft is tracked by radar and then the Parkes Radio Telescope to the moon-ship 50,000 miles into space. There is now no question that the aliens are real and the case becomes a Security matter. Although the Soshun sends Bernie, Jean and Peter back to Earth, Prof. Mayer stays on Soshuniss to learn more about it. Meanwhile, at the end of the episode, Adam and Varossa have escaped from prison and await rescue from Soshuniss.

Episode 6

In the final episode, matters come to a head. Bernie, Jean and Peter are pressured by the authorities to reveal where the Soshunites are hiding, as they are now considered alien spies. However, the Soshun has returned Prof. Mayer to the United Nations in New York, repeating her request to be allowed to settle in Australia in exchange for Soshunian scientific knowledge. He convinces a UN Special Committee and just as Adam and Varossa are about to be re-arrested by the police, word comes through that the UN has accepted the Soshunites' offer and they will be allowed to settle on Earth. The episode concludes on what is both a happy ending and a cliffhanger suggesting there is still more of the story to come….

TV Times preview article from April 1964 promoting the premiere of The Stranger

Australia's Answer to Doctor Who?

Although The Stranger is classed as a children’s programme, it has much to hold the attention of an adult viewer, just like Doctor Who, to which it is now being compared. However, producer Storry Walton dislikes the comparison and believes that the Australian show is more creative and has better production values, with more sequences filmed on location. Locations for the series included St Paul's University College in Sydney (in the role of St Michael’s school), the Blue Mountains, exteriors at the ABC headquarters campus (masquerading as various locations, including Idlewild Airport!) and Canberra.

On the set during the production of The Stranger while filming a scene on Soshuniss. Adam tells the trio from Earth that the Soshunites originally wore their hair long, but have cut it to fit in more comfortably on Earth.

Both Mr. Saunders and the Production Designer, Mr. Geoffrey Wedlock paid particular attention to portraying the Soshunians as a plausible, but alien, extraterrestrial society. Mr. Saunders created a language for the inhabitants of Soshuniss to speak among themselves, and it is believably and naturalistically spoken by the actors. When they speak English, all the Soshunians have a European-sounding accent, signifying that they are not speaking their native language. One of Saunders’ characteristic twists is that the Soshun is a woman, rather than a man as might be expected, and that her title is also the word for “mother”: Soshuniss therefore means “the motherland”. The CSIRO was also engaged to advise on the design of the Soshunian “flying saucer”, to make it as plausible a spacecraft as possible.

Underneath its well-crafted juvenile surface story, The Stranger also touches on some important issues including the treatment of refugees and European migrants to Australia and the concerns that many people are starting to have about industrial pollution damaging the environment. Although the “accident” that poisoned the Soshunian’s home planet is not specified, there are hints that its environment may have been destroyed by some kind terrible industrial accident that released toxic chemicals.

Veteran actor Ron Haddrick, well known to Australian viewers, gives adult nuance to his performance as Adam Suisse, the titular Stranger

The cast of The Stranger, while mostly actors well known in Australia, would not be familiar to those of you overseas, but I must mention the distinguished theatrical performer Ron Haddrick, who played the part of Adam Suisse without the least condescension to the younger viewers at whom the show is aimed, much like William Hartnell approaches his role on Doctor Who.

Coming Soon

The second series of The Stranger is due to start in July this year and hints of the new storyline are beginning to emerge. Storry Walton mentioned in a recent interview that the second series would complicate the political situation surrounding the Soshunians request to live in Australia, with a suggestion that doubts would begin to grow about the good intentions of the aliens. I’m quite looking forward to this new series and perhaps those of you in Britain and the US may get to see it too, as the BBC has already bought the first series for screening next year and there are rumours that it may be bought by a US network as well.

![[April 26, 1965] A Stranger in a Strange Land (The Stranger, Australian TV SF)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Stranger-8a-672x372.png)

![[April 24, 1965] Every Silver Lining Has A Cloud (May 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Fantastic_v14n05_1965-05_0000-2-672x340.jpg)

![[April 22, 1965] Cracker Jack issue (May 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650422cover-575x372.jpg)

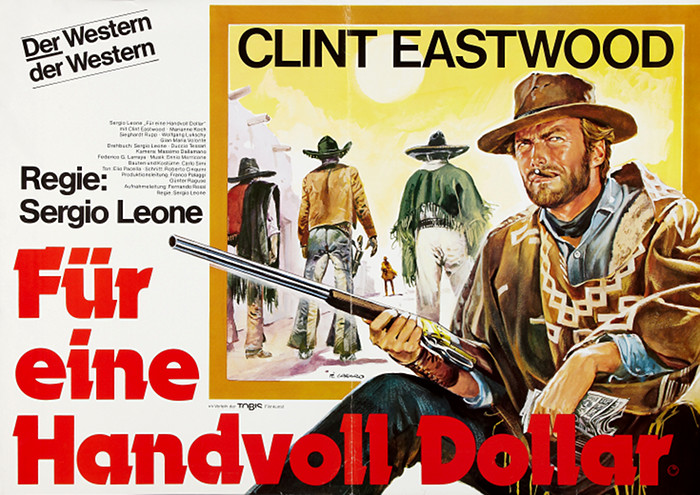

![[April 20, 1965] Less Satanic Than Expected (John Sturges' <em>The Satan Bug</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650422_movieposter-672x372.jpg)

![[April 18, 1965] The Doctor, the King and the Sultan (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Crusade)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650418cover-672x372.jpg)

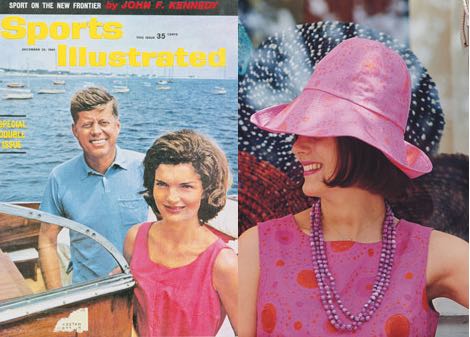

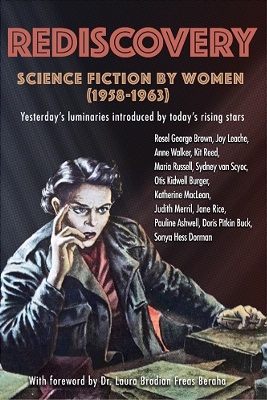

![[Apr. 16, 1965] The Second Sex in SFF, Part VIII](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650416cover-521x372.jpg)

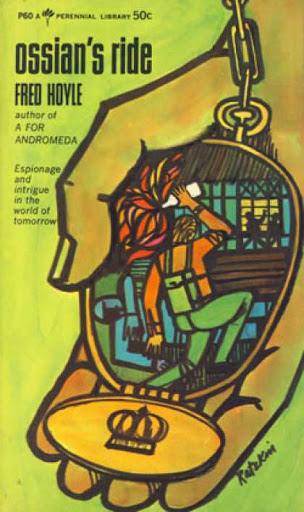

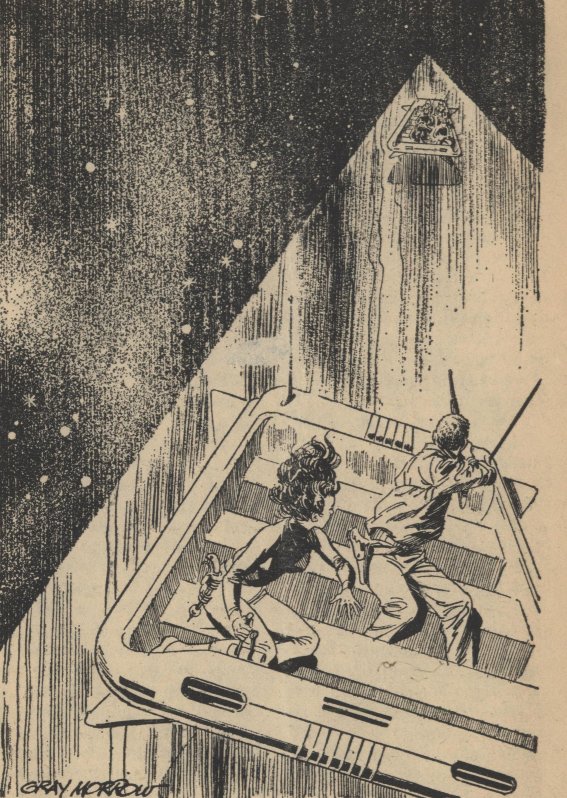

![[April 14, 1965] Furious Time Travel (April Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650414coversnew-672x372.jpg)

![[April 12, 1965] Not Long Before the End (May 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650412cover-672x372.jpg)

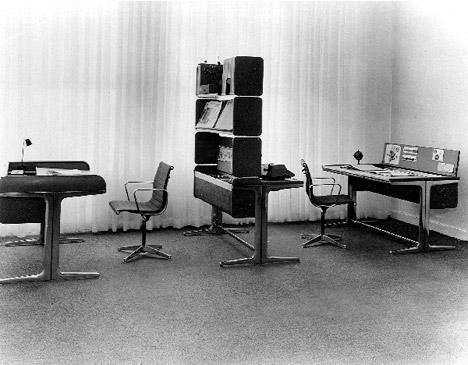

![[April 10, 1965] Furnishing the Home of the Future: Interior Design for the Space Age](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/39340889-672x372.jpg)