by Gideon Marcus

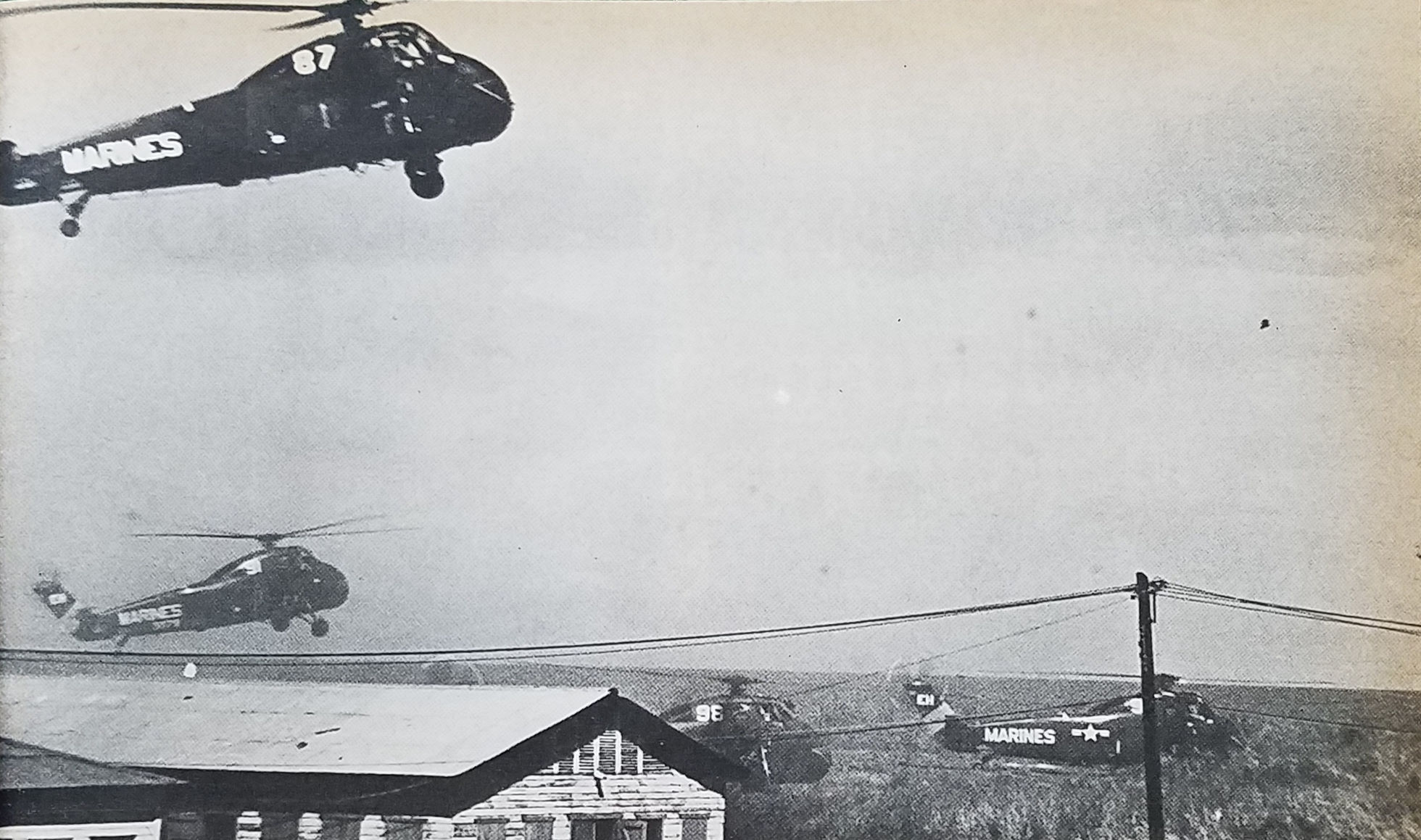

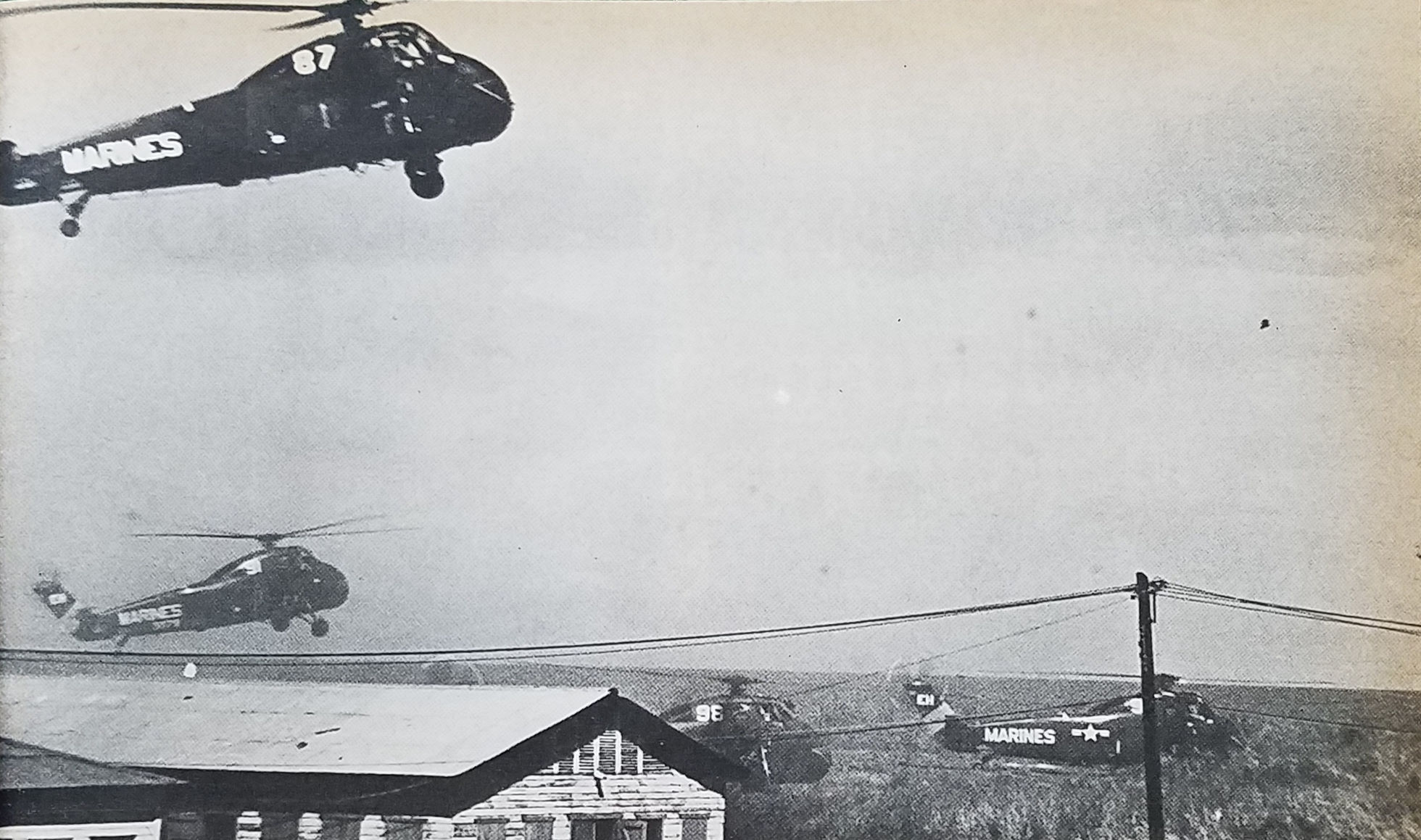

Pirates of the Caribbean

The Dominican Republic, half of the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean, has never been a beacon of democracy. The Trujillo dictatorship lasted three long decades, ending only in 1961 after his assassination. The nation's first democratic elections, in 1963, brought Juan Emilio Bosch Gaviño to the Presidency. In the same year, a military junta removed him from power, elevating Donald Reid Cabral to the position.

Reid was never popular, and on April 24, military constitutionalists and Dominican Revolutionary Party supporters launched a coup, José Rafael Molina Ureña taking the top post. He lasted all of two days. A counter coup restored the Reid government to power, although Reid, himself, had fled the country.

Meanwhile, the American military worked to evacuate some 3,500 U.S. citizens living in the country. Just this morning, elements of the 82nd Airborne Division landed at San Isidro Air Base, on the outskirts of Santo Domingo. Their mission is to enforce a ceasefire and guide the country back to democracy.

Thus, our nation is now involved in stabilizing missions on both sides of the globe. Will this action mark a long term involvement? Or, in the absence of a Communist menace (Haiti is not North Vietnam!) and with the aid of other O.A.S. nations, will this be a quick exercise to hasten Caribbean democracy?

Only time will tell.

Insurgency in the Old Country

At the very least, we can be certain that the Dominican involvement has no chance of developing into a nuclear confrontation (unlike Vietnam, where Sec. Def. MacNamara did not rule out that possibility). So it's a conventional affair for now.

Appropriately, we now turn to the most conventional of science fiction magazines, the oft-hidebound Analog. Like the Dominican Republic, it has been under a single strongman for several decades. And yet, like that island nation, we occasionally see signs of progress. Indeed, this latest issue has some refreshing entries, indeed.

by John Schoenherr

Trouble Tide, by James H. Schmitz

On the world of Nandy-Cline, herds of sea cows are abruptly and mysteriously disappearing from the costs of the Girard colonies. Danrich Parrol, head of the Nandy-Cline branch of Girard Pharmaceuticals, teams up with Dr. Nile Etland, head of Girard's station laboratory, to find the cause of the vanishing food animals. They suspect foul play from a rival company, Agenes. The poisoning of a herd of mammalian but native fraya seems somehow connected, too. The two embark on a forensic adventure that takes them across a thousand miles of coast and under miles of ocean.

by John Schoenherr

There are many features that make Tide stand out. What a delightful story this is, with an interesting pair of protagonists and a cute scientific solution. I appreciated the depiction of a planet as a big place, big enough to support many economies, colonies, and criminal activities. I also particularly liked the appearance of female characters. Indeed, Dr. Nile Etland is an equal partner in the investigation and is not a romantic foil — simply a competent scientist.

Why is this remarkable? I had become so inured to the lack of female characters in my science fiction that I'd almost started to challenge my convictions. Was it really fair of me to judge fiction (at least in part) by whether or not it included female characters? Isn't modern SF just a reflection of the male-dominant society we live in? Can we blame authors for writing "what they know?"

Yes, yes, and yes. The erasure of women in any kind of fiction, particularly one that projects present trends into the future, is inexcusable. Any portrayal of a world where women play minor roles or none at all isn't just unrealistic, it propagates a kind of ugly wish fulfillment. That's why, when I get a story like Tide with realistic and positive representation of women (and, indeed, Schmitz has always been good in this regard) it's such a breath of fresh air. Ditto the British import show, Danger Man, which regularly features competent professional women who are integral to the episodes.

It's what I want to see. It's what I should be seeing. That I'm seeing it in Analog of all places gives me hope.

Four stars.

Planetfall, by John Brunner

by Alan Moyler

A young Earth woman eagerly greets a young astronaut man, an ecologist on the crew of a starfaring colony with 2,500 residents that is making a brief stop. She's set on falling in love with and departing with this exotic fellow, who represents freedom, the exotic, and most of all, purpose in life.

He, on the other hand, wants nothing more than to jump ship, to escape the stultifying space-kibbutz life, to experience the beauty of humanity's Home.

Each of them poison each other's greener grass, and the encounter is an unhappy one.

If there's such a thing as a "meet cute," then this is a "meet ugly," but it's quite poignant. Brunner does good work. Four stars.

Magnetohydrodynamics, by Ben Bova

I really wanted to like this nonfiction article. After all, it's about a genuinely scientific topic, a revolutionary one. MHD allows the generation of power without moving physical parts, instead using magnetic fields and plasma. It's the kind of technology required if we ever want to build fusion power plants. Plus, Asimov likes the guy.

But boy is this piece dull. It's not quite as dry as reading a patent, but it's in the same ballpark. I've heard similar reviews of Bova's work in other magazines, so I can't be the only one who feels this way.

Anyway, two stars.

The Captive Djinn, by Christopher Anvil

by John Schoenherr

Captured human on a planet of cats at a 19th Century technology level outwits his jailers through the use of basic chemistry and the exploitation of the felines' stupidity.

If there were an award for "Story that best exemplifies Chris Anvil's work for John Campbell," this would win. Two stars.

Beautiful art by Schoenherr, though. He's definitely going to get a Galactic Star again this year!

The Prophet of Dune (Part 5 of 5), by Frank Herbert

And now we come to the greatest coup of all, the finale of the longest serial I've ever read in a magazine.

Technically, Dune is two serials, and there have been other five-part novels. But Prophet of Dune is not a sequel to Dune World but the latter "novel's" conclusion.

It's been a long trek. It started with Duke Leto Atreides acquiring the fiefdom that included Arrakis, a desert planet and the only source of the spice melange. This cinnamon-smelling spice is an anti-agathic and also conveys a limited form of precognition.

For the Empire's rich, it livens food and lengthens lives.

For the Navigators' Guild, the spice allows its specialists to navigate the hazardous byways of hyperspace.

For the Bene Gesserit, a religious order of women, it facilitates their plans to manipulate history through the deliberate mixing of blood-lines; their hope is to eventually produce the "Kwisatz Haderach," a sort of messiah, a man with the powers of the Bene Gesserit.

Duke Leto was not long for his reign. The Harkonnen family from whom Arrakis was transferred immediately schemed to regain it, attacking the planet, killing Leto, and forcing Leto's concubine, the Bene Gesserit Jessica, and their son, Paul, to go into hiding among the native "Fremen." So ended the first serial.

by John Schoenherr

Baron Harkonnen installed a ruthless nephew on Arrakis with the goal of fomenting a rebellion. His plan would then be to take personal control, relax the tyranny, and turn the Fremen into the greatest army the Empire had ever seen, even more fearsome than the Saudukar, the Imperial guard.

Out in the desert, Paul spends a harsh two years learning the ways of the desert. Moisture is priceless, and all sand-dwellers wear water-recycling "still-suits." The voracious sandworms are both a constant threat and a valuable commodity, for it is their waste that is refined into spice.

While among the Fremen, Jessica becomes a Reverend Mother, transforming poisonous sandworm effluence into a substance that allows her to commune with all of her brethren, living and dead. Because she does so while pregnant, her unborn daughter, Alia, gains the wisdom of a thousand women and is born an adult in a child's body.

Paul is initiated into Fremen culture, eventually assuming the mantle of Muad'Dib, savior of the desert people. Under his leadership, the Fremen are united. They will revolt, as Harkonnen expected, but the event will not unfold as the Baron desires.

In this final installment of Dune, Paul launches his attack even while the Padishah Emperor, himself, has visited the planet with five legions of Saudukar, and all of the great families have surrounded Arrakis with warships. But the hopeless position of Muad'Dib turns out to be unbeatable: for Paul controls the production of spice. Without it, the nobility is crippled, space is unnavigable. Thus young Atreides emerges utterly triumphant with virtual control of the Empire, a bethrothal to the Emperor's daughter, and freedom for the people of Arrakis.

I have to give credit to Frank Herbert for creating a universe of ambitious scope. There's a lot to Dune, and the author clearly has a penchant for world-building. He takes from a wide variety of sources, particularly Arabic and Persian, creating a setting quite different from what we usually see in science fiction. The result is not unlike the landscapes generated by Cordwainer Smith, whose upbringing included time in China, or Mack Reynolds, whose writing is informed by extensive travel behind the Iron Curtain and in the Mahgreb.

But.

There's plenty not to like, too. Herbert is an author of no great technical skill, and his writing ranges from passable to laughably bad. There wasn't so much of his third-person omniscient and everywhere-at-once in this installment, but it wasn't completely absent, either. The writing is humorless, grandiose (even pompous), and generally not a pleasure to read.

Beyond that, the work is highly reactionary. I was originally pleased to see several female characters in the story. Lady Jessica often is the viewpoint, though given Herbert's love of switching perspective every third line, that's not quite so noteworthy. But in the end, even the most prominent women are limited to their medieval roles, that of wife and bearer of greatness. Dune is a man's world.

Then there are the fedayken, the people of the desert clearly modeled on the Arabs. And who should lead them to freedom? Not a local son, no; only T. E. Lawrence Jesus Atreides can save them.

It's an unsettling subtext in our post-colonial times: a galactic empire, decadent and crumbling, requires an infusion of European boldness to restore it to vigor. Is it any surprise that this novel came out in Analog?

So, on the one hand, I give this installment four stars. It kept me interested, and I appreciated the intricacy of the conclusion. Looking over my tally for the other seven parts of this sprawling opus, that ends us at exactly three stars.

I think that's fair. Some will praise the book for its vision and be undaunted by the quality of the prose or the offensiveness of its underpinnings. Those folks will probably nominate it for another Hugo next year. Others will give up in boredom around page 35. I read the whole thing because I had to. I didn't hate it; I even respect it to a degree. But I see its many many flaws.

Let the adulatory/damning letters begin!

Running the Numbers

Once again, Analog finishes at the top of the heap; at 3.3 stars, it ties with Science-Fantasy. It's been a good month for fiction overall, with New Worlds and Amazing scoring 3.2.

Fantastic gets a solid 3 stars, and IF just misses the mark at 2.8.

Fantasy and Science Fiction disappoints with 2.7, though its Zenna Henderson story may be the best of the month.

While women may be making a comeback as fictional characters, as writers, they're still conspicuously absent. Only 2 of the 38 fiction pieces were written by women.

Perhaps it's time for a coup. Summon the 101st Airborne!

Our last three Journey shows were a gas! You can watch the kinescope reruns here). You don't want to miss the next episode, May 9 at 1PM PDT, a special Arts and Entertainment edition featuring Arel Lucas, Cora Buhlert, Erica Frank…and Dr. Who producer, Verity Lambert! Register today and we'll make sure you don't forget.

![[May 16, 1965] Gathering Dust (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Space Museum)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/peekadoctor-672x372.jpg)

![[May 14, 1965] Keep A Civil Tongue In Your Head (July 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n02_1965-07_0000-2-672x318.jpg)

![[May 12, 1965] Da Capo (June 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/amz-0665-cover-391x372.png)

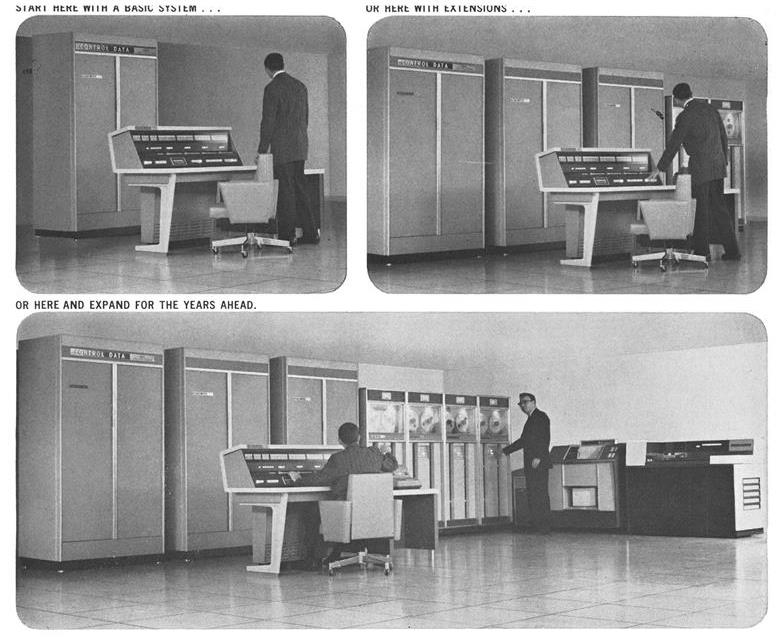

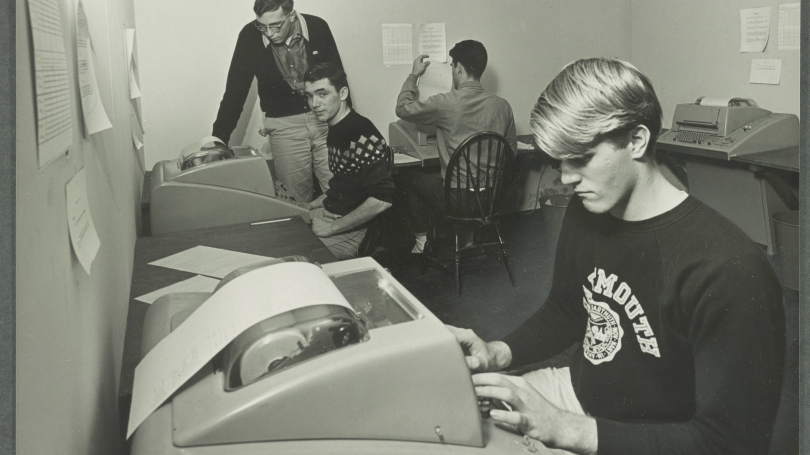

![[May 10, 1965] A Language for the Masses (Talking to a Machine, Part Three)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650510jennifer-662x372.jpg)

![[May 8, 1965] Skip to the end (June 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650508cover-535x372.jpg)

![[May 6, 1965] Back To Our Roots (<i>New Writings in SF4</i> & <i>Over Sea, Under Stone</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/New-Writings-and-Over-Sea-Under-Stone.jpg)

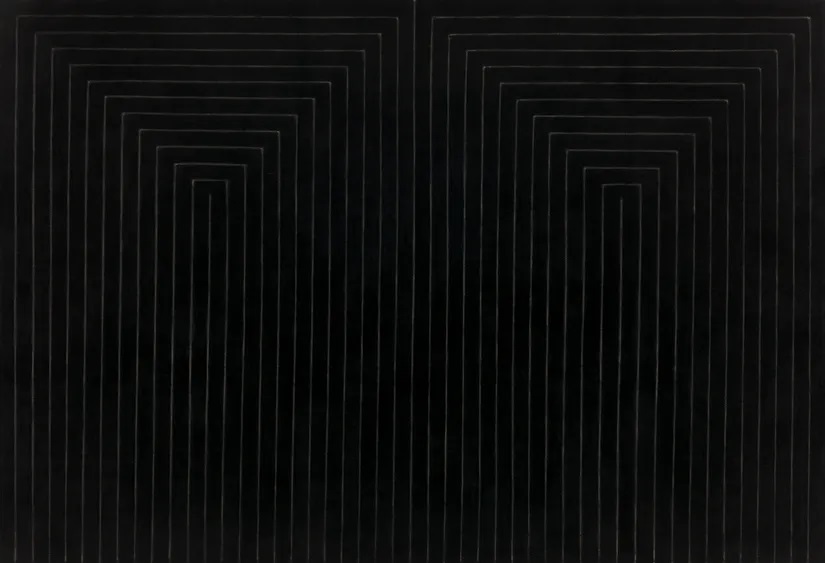

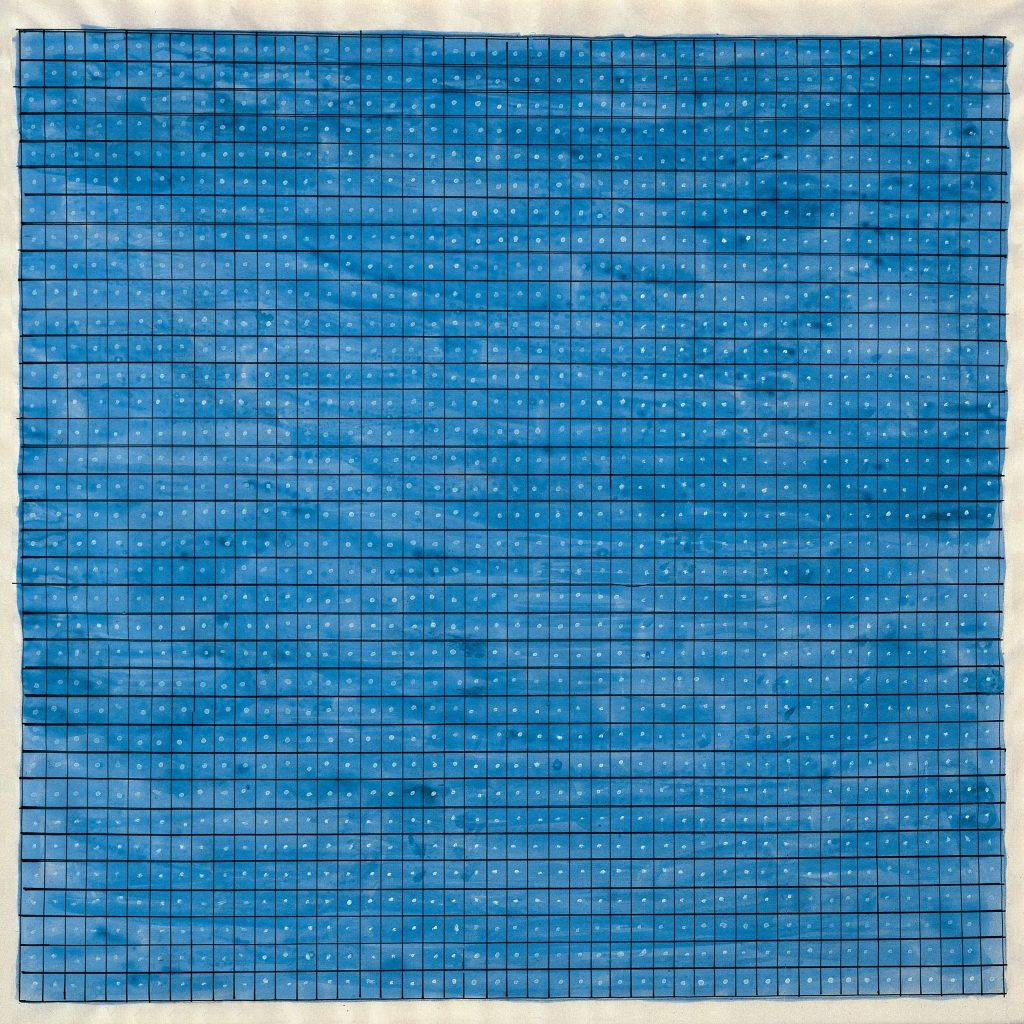

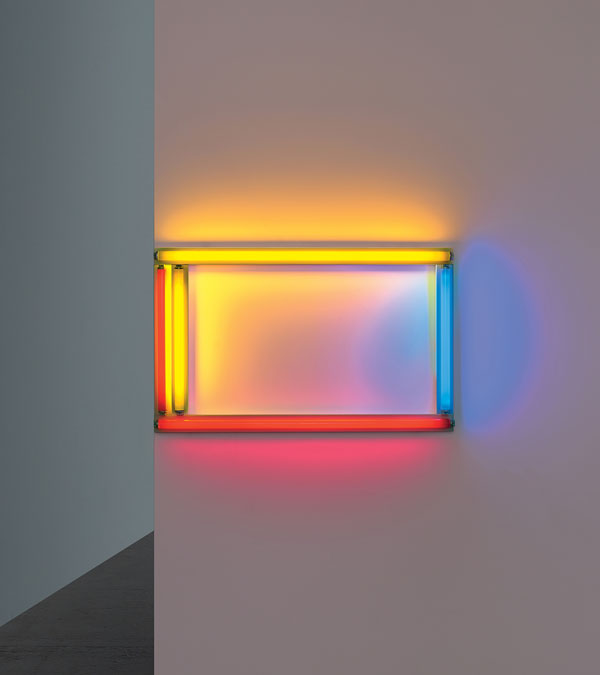

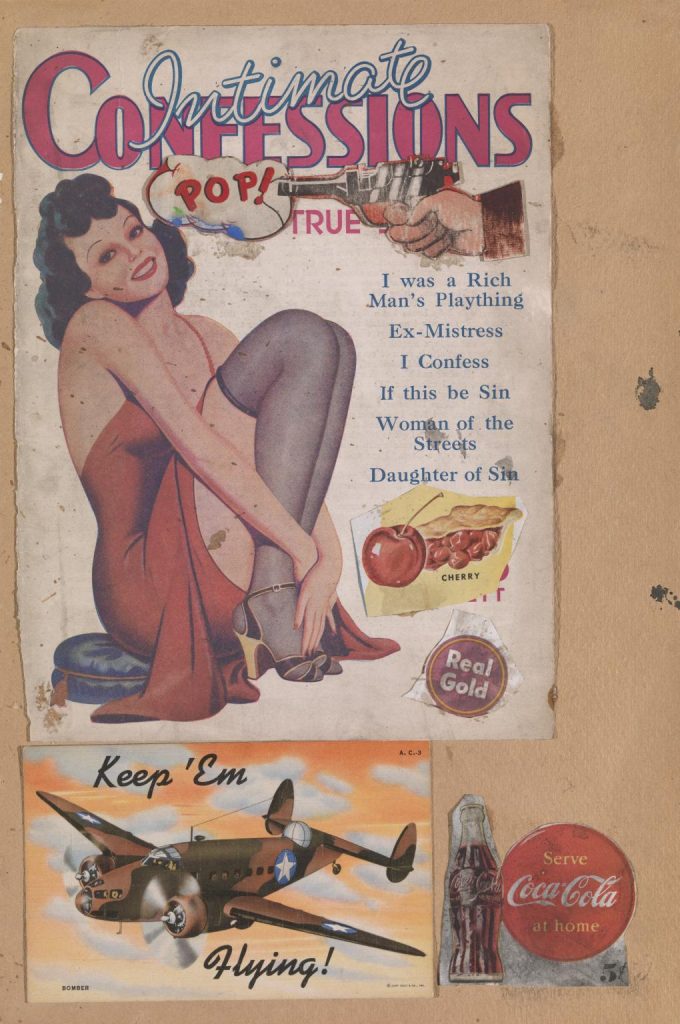

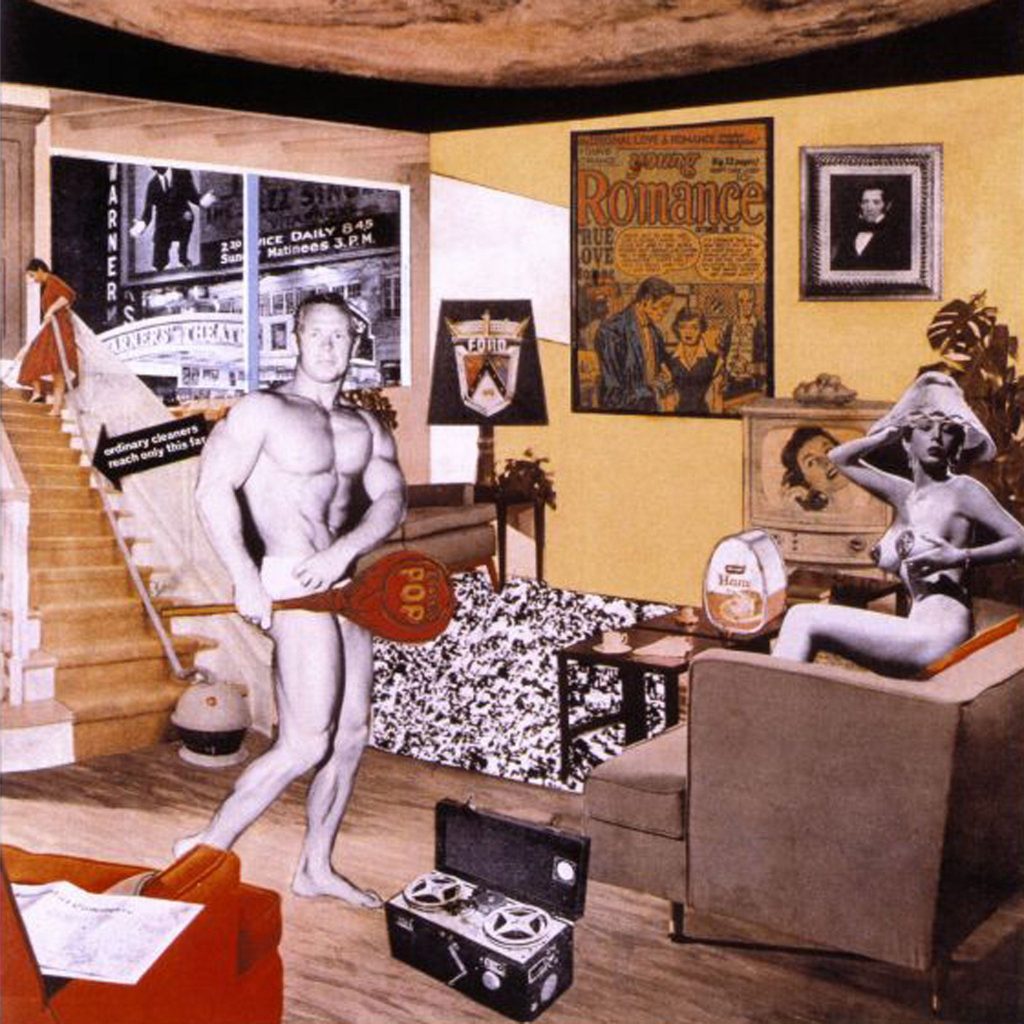

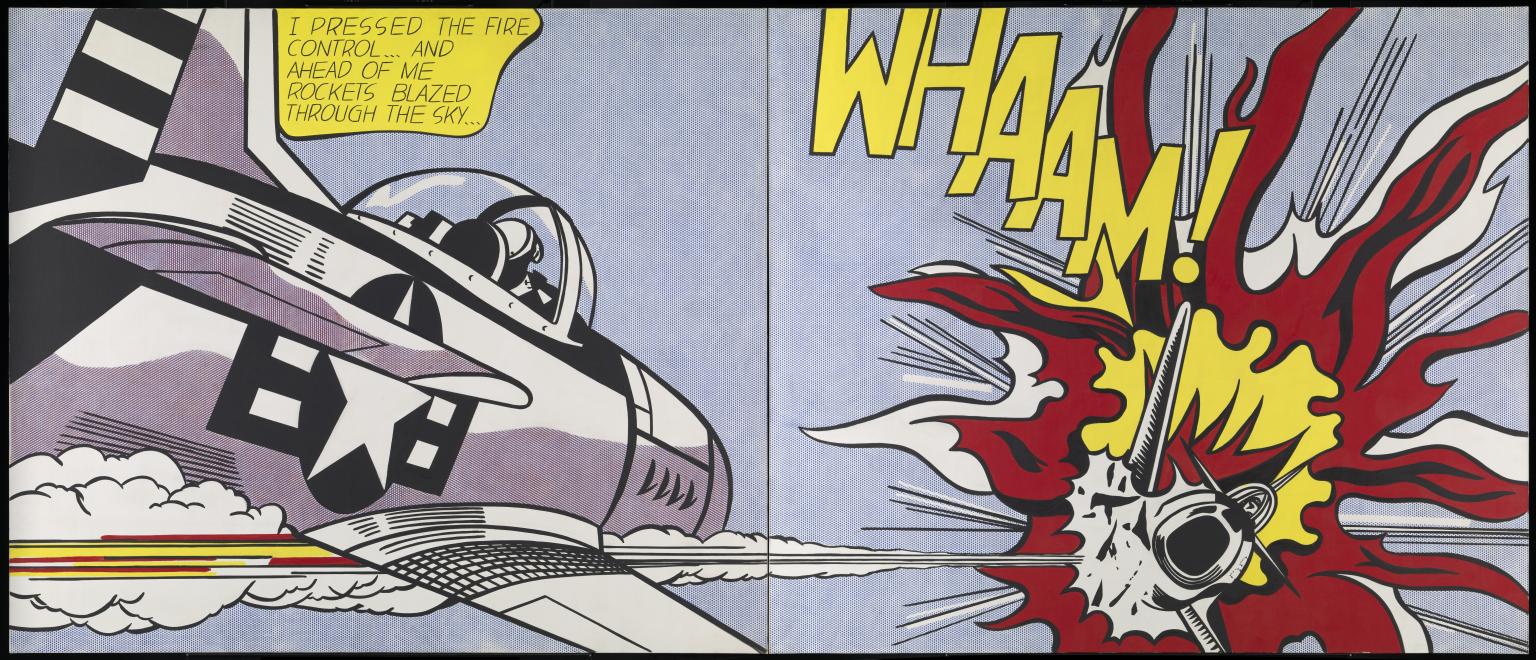

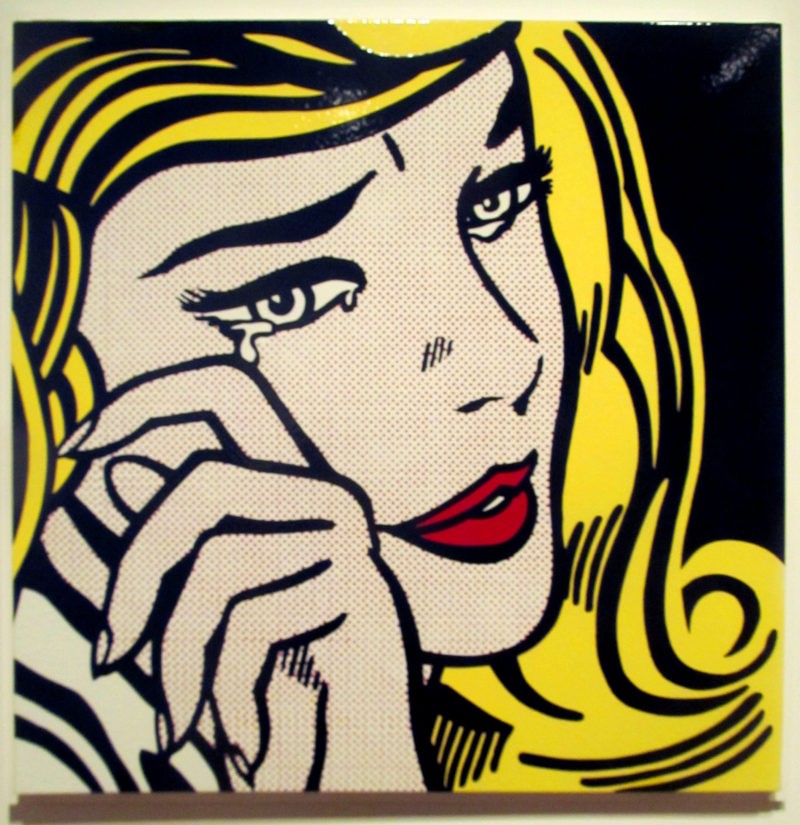

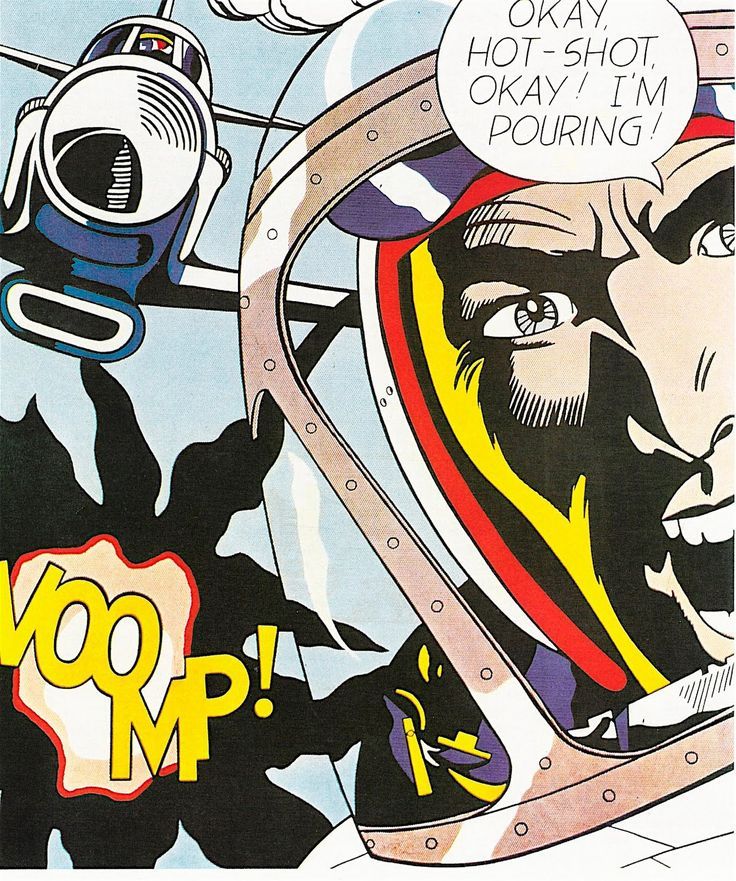

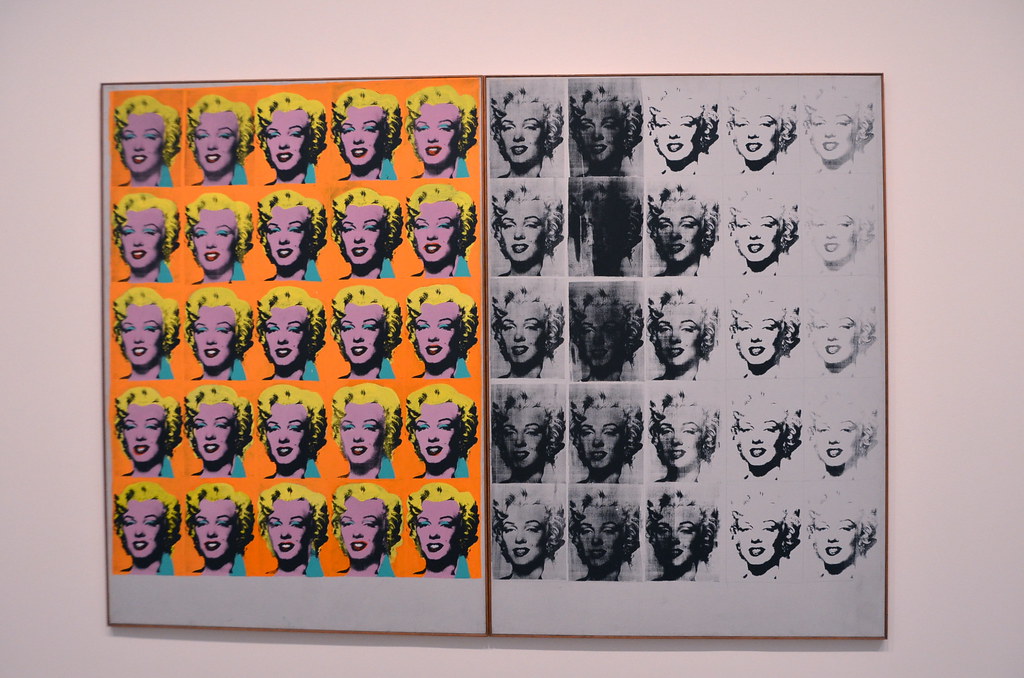

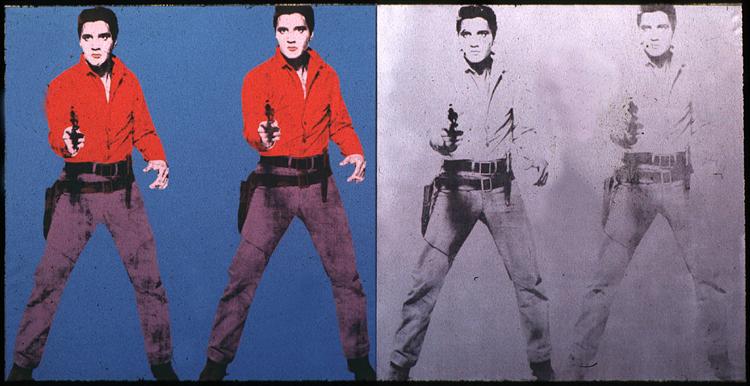

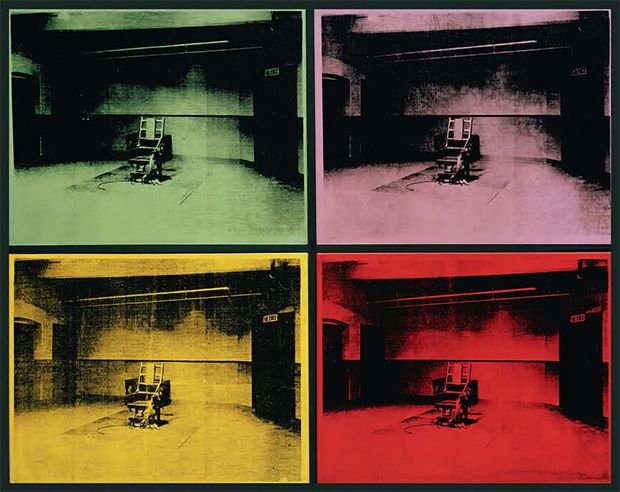

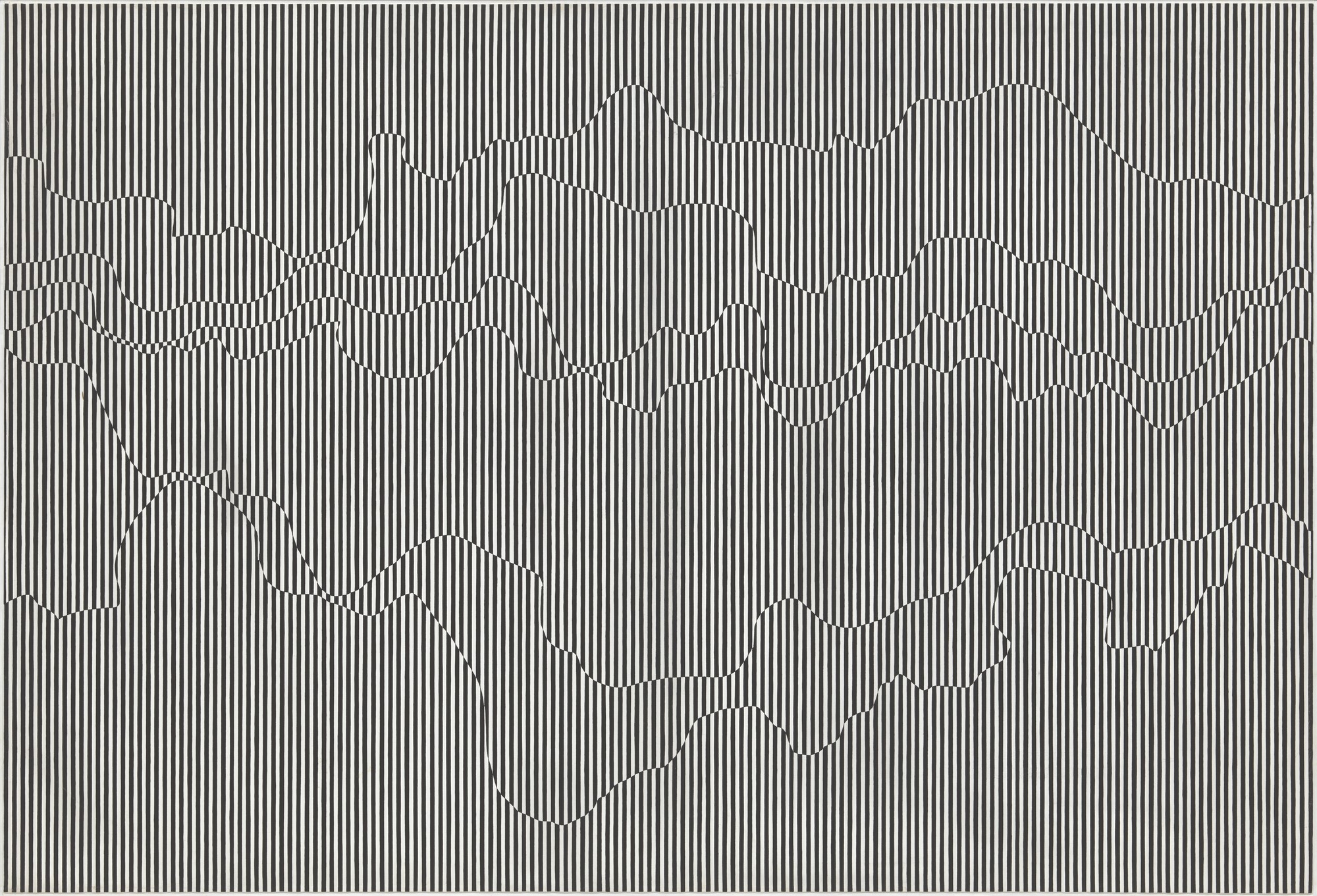

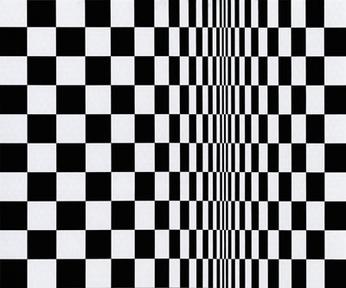

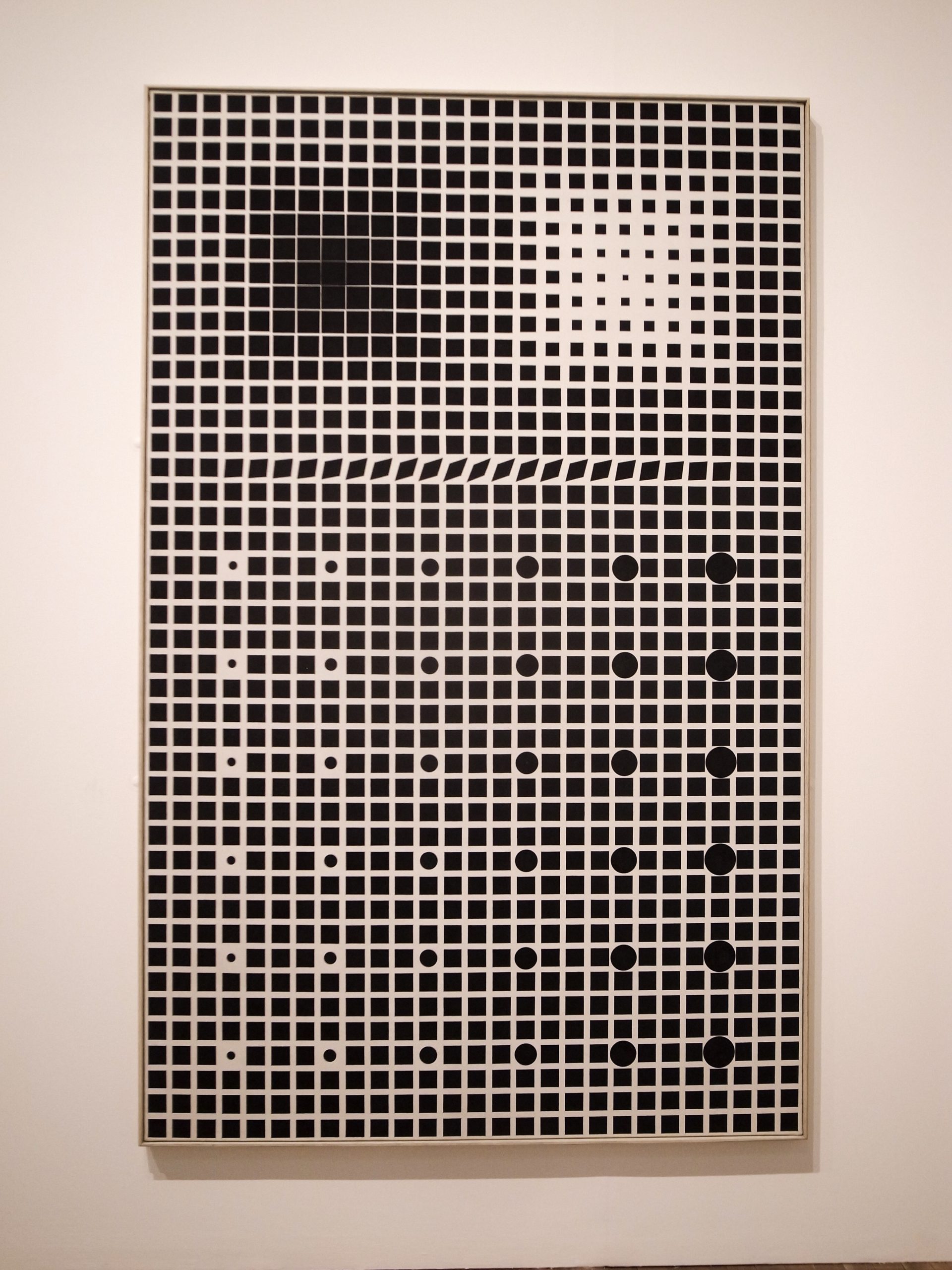

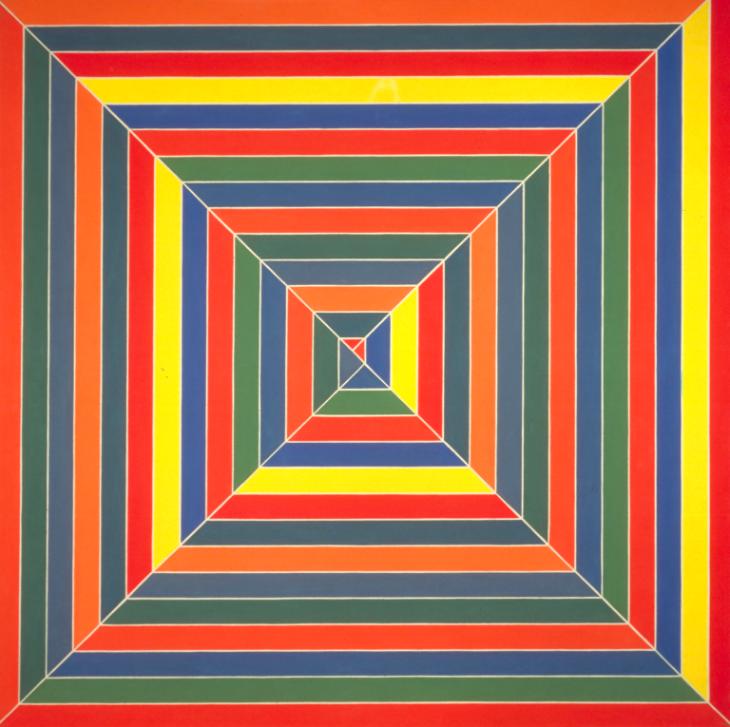

![[May 4, 1965] The Op and the Pop: New Movements in Modern Art](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/cri_000000237355-1140x1150-1-672x372.jpg)

![[May 2, 1965] FORWARD INTO THE PAST (June 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/IF-June-1965-cover-647x372.jpg)

![[April 30, 1965] Back-door uprising(May 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650430cover-663x372.jpg)