by Victoria Silverwolf

It's Great To Be Back

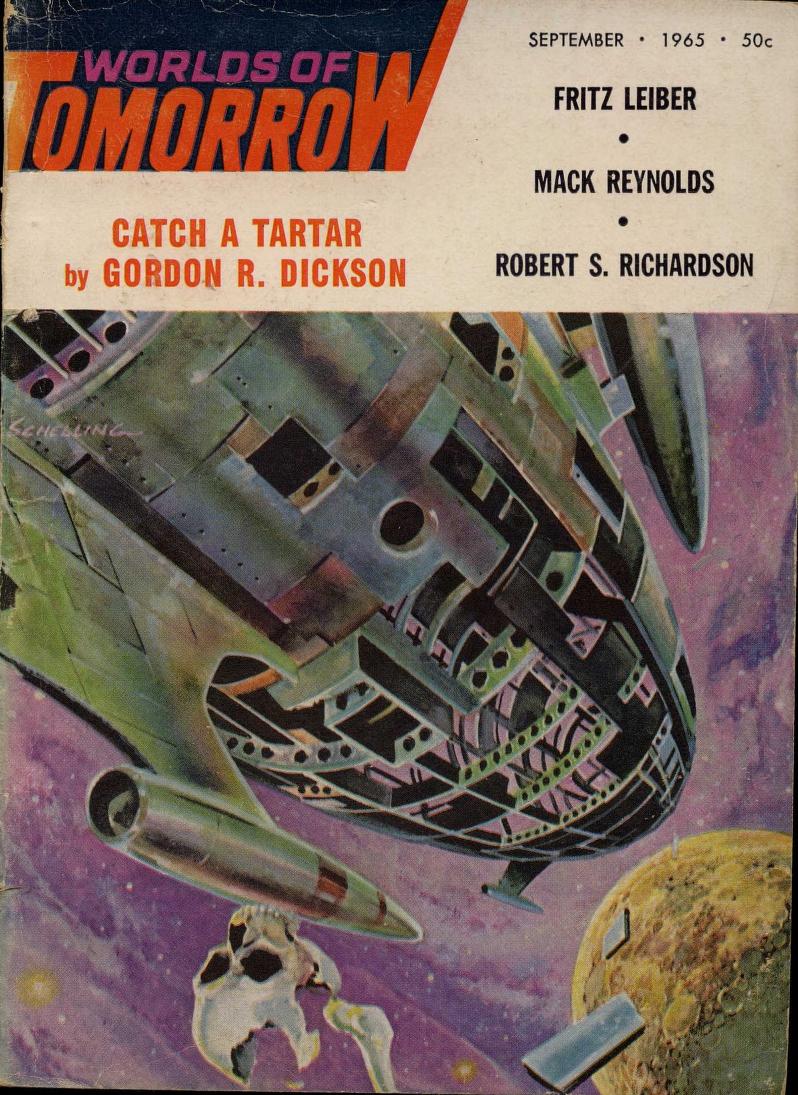

Those of you who keep track of minutiae may have noticed that I haven't been around these parts for a while. Blame it on seismic changes in the world of magazine publishing. To wit, the fact that Fantastic will now be published bimonthly removed that magazine from the newsstands for a couple of months, in order to have it alternate with sister publication Amazing. I had to wait until the latest issue of Worlds of Tomorrow arrived on my doorstep before I could get back to the typewriter and churn out a review. Let's get started, shall we?

Absence Makes The Heart Grow Fonder

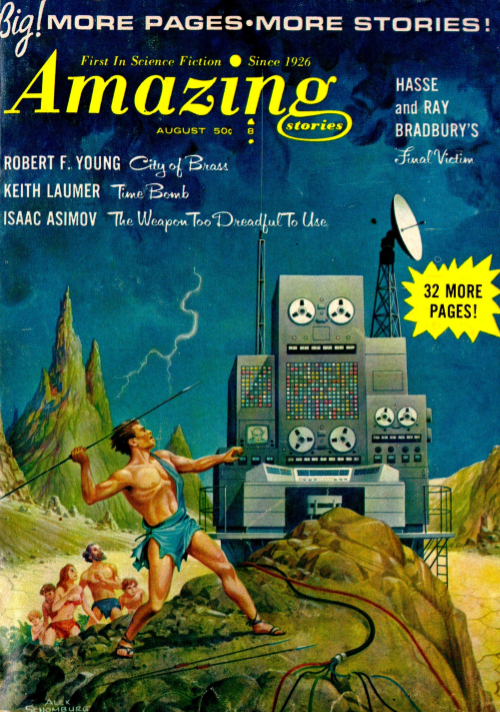

Cover art by George Schelling, illustrating a macabre scene from Fritz Leiber's story

Maybe it's only because I haven't done this for a while, but I look forward to analyzing this issue with more enthusiasm than usual. Let's see if I retain my critical passion as we make our way through the crisp white pages of the youngest member of Frederik Pohl's family of publications.

Catch a Tartar, by Gordon R. Dickson

The hero of this lighthearted romp through the cosmos is one Hank Shallo, a jolly giant of a man, fond of beer and singing. When he's not belting out a tune or quaffing a brew, he works as a deep space scout, seeking out new planets for humanity. The woman who gives him his assignments is a certain Janifa Williams, a statuesque blonde who would like him to settle down on Earth with her.

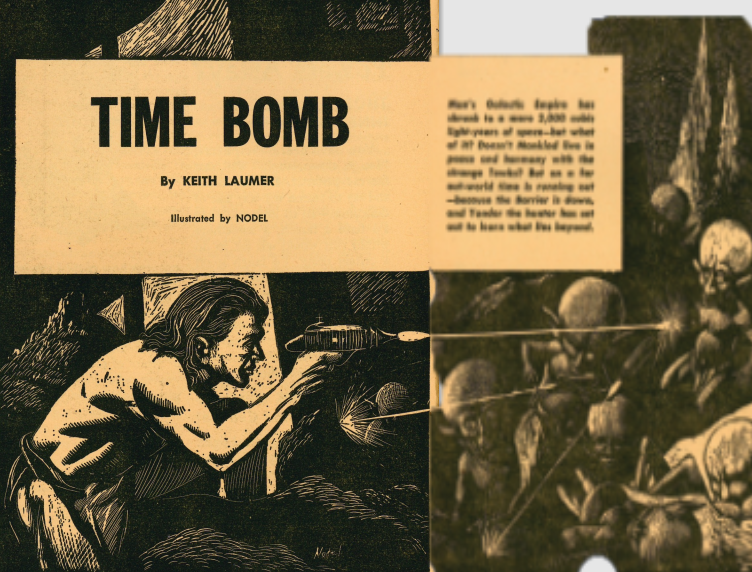

Illustrations by Norman Nodel. This is not Janifa, by the way, but a no-nonsense physician who treats our hero for a hangover.

Janifa arranges to meet Hank on a colony world with a serious problem. It seems that the computer that controls the planet's environment, so people can live there, thinks it's a god. It demands a human sacrifice before it will go back to work. Hank is the lucky fellow who's supposed to be offered up to the mechanical deity. There's an escape plan, but Hank has a scheme of his own.

Hank arrives.

Complicating matters is the presence of the guy who created the computer, a mad genius who is in love with Janifa. Hank has to figure out a way to defeat the computer, save Janifa from the unwelcome advances of the scientist, and retain his happy-go-lucky lifestyle.

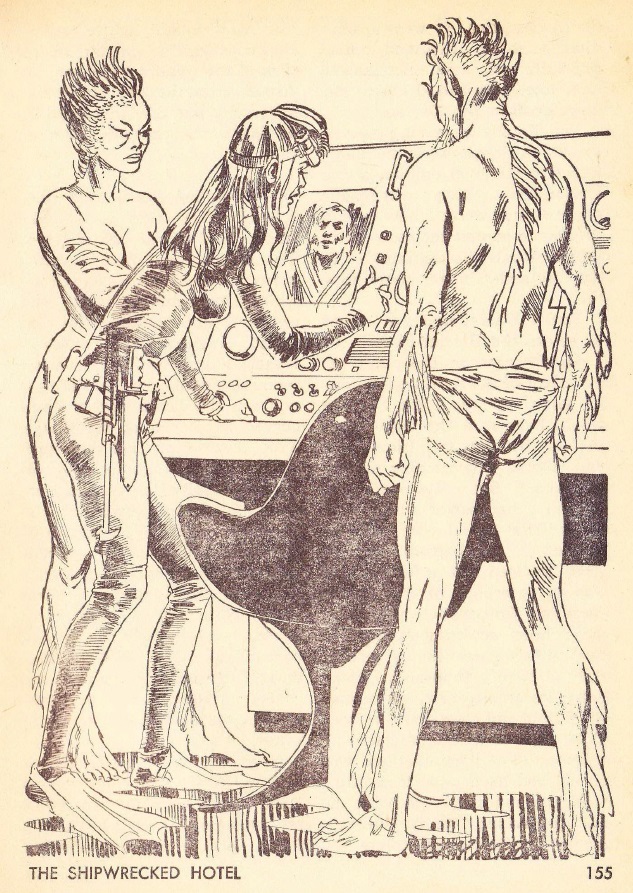

The madman, Janifa, and a few of her many admirers.

Hank is a likable rogue and something of a con artist, as he uses his wits to get the better of everyone. I found the story to be more enjoyable than most attempts at science fiction comedy, which tend to be full of sophomoric slapstick. The female characters are decorative, to be sure, but also intelligent, competent, and professional. It's not the most profound tale in the world, but worth reading.

An amused three stars.

The Light Outside, by C. C. MacApp

This strange little story consists of a series of messages, ranging from prayers to scholarly articles, over a very long period of time. (That's true in one sense, but not in another. Confused? That's how I felt when I started reading.) We eventually figure out that the beings responsible for these writings live at a much faster pace than those who are observing them, known as the Watchers. At the end we learn something more about the Watchers, and those who are watched.

The narrative structure tends to have a cold, distant feeling to it, so it's hard to connect with the story on an emotional level. On the other hand, the premise is original and interesting.

An intrigued three stars.

The Tinplate Teleologist, by Arthur Sellings

Illustration by Brock. I have been unable to find out anything about this artist, not even his or her full name.

Davie — more formally, DA 38341 — is an obsolete household robot, kicked out of his home when a more advanced model takes his place. He has a limited amount of time to find somebody to purchase him, at a price hardly anybody is willing to pay for an old machine. If he fails, he goes back to the factory to be turned into scrap metal.

The episodic plot follows Davie as he meets a sympathetic but powerless dealer in used robots, a bitter robot who plans to rob a human being, the elderly inhabitants of a retirement community who welcome his help, but can't afford to pay for him, and an impoverished painter who finally gives him the opportunity to save himself from the junkyard.

This sentimental yarn feels like a science fiction fairy tale. Davie is one of those meek, gentle characters who overcome all obstacles with quiet bravery. Mix a little Asimov with a little Bradbury and you might have something like this slick tearjerker.

A wistful three stars.

Theories Wanted, by Robert S. Richardson

The author presents various astronomical mysteries, offers hypothetical solutions, and suggests that amateurs might be able to help professionals figure things out.

I had to let out a weary sigh when the article began with the hoary old chestnut of trying to account for the Star of Bethlehem in scientific terms. To nobody's surprise, Richardson thinks a nova is the most plausible explanation, if any is needed. (I guess he's read Arthur C. Clarke's decade-old story The Star.)

I was more interested in the peculiar star Mira Ceti, which varies in brightness in irregular ways. It also has a much fainter companion star, difficult to observe, which presents a similar enigma. I would have preferred an entire article about Mira Ceti.

Other subjects include the Trojan asteroids, which occupy a stable point in Jupiter's orbit, and a comet known as P/1925 II. Like a smorgasbord, there are several items to choose from, and not all of them are tasty.

A highly variable three stars.

At the Institute, by Norman Kagan

Illustrations by Gray Morrow

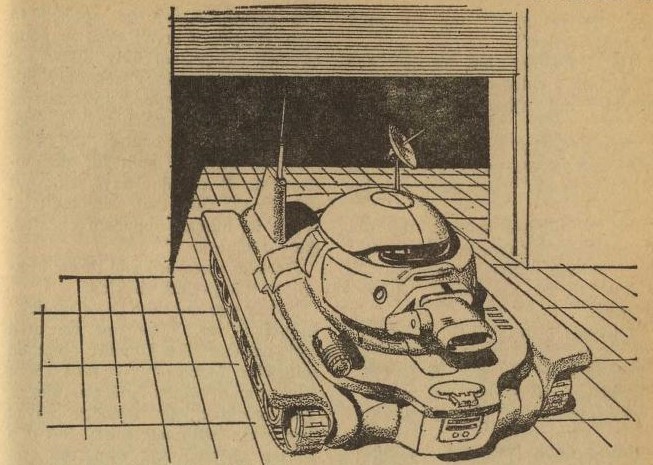

This razor-sharp satire takes the narrator through the halls of a research institute full of eccentric scientists involved in outrageous projects. We get our first hint of how wild things are going to get when he has to ride a tank (see above) through a ring of solid uranium to get into the place. After encountering a number of researchers working on experiments as bizarre as anything found in Jonathan Swift's Balnibarbi and Laputa, he meets the director of the place.

The infantile director and the narrator, facing the institute's defense system. Please excuse the way I had to fold the magazine to show you the whole picture.

Although the narrator seems at first to be the voice of sanity, exposing the madness of so-called pure research, it turns out that his own more practical studies are equally insane. The author casts a jaundiced eye at all aspects of science and government.

The story moves at a breakneck pace, with jokes, puns, paradoxes, and lampoons of human foibles in nearly every sentence. The tone reminds me of the recent novel Catch-22 by Joseph Heller, in the way it mixes surreal comedy with a dark view of humanity's tendency to destroy itself.

A sardonic four stars.

Cyclops, by Fritz Leiber

Three astronauts set out on a journey to investigate why an interstellar vessel, under construction in orbit around the Moon, is out of communication with Earth. Similar problems in the past turned out to be minor, so the spacemen aren't too worried. During the voyage, they discuss the possibility of life existing in empty space. Since one of the astronauts is psychic, it's not a big surprise that their speculations turn out to be all too real.

Although the plot is predictable, this is an effective science fiction horror story, full of striking images. As you'd expect from Leiber, it's very well written. A minor work from a major author.

A frightened three stars.

Of Godlike Power (Part Two of Two), by Mack Reynolds

Illustrations by Jack Gaughan

Let's recap. Part One of the novel took us to a near future United States of flying cars and automated bars. More importantly, it's a place where most people are unemployed, but enjoy a reasonably comfortable life in a prosperous welfare state. The protagonist is the host of a radio talk show dealing with UFO's and other speculative stuff. His job leads him to an eccentric preacher who has the ability to prevent people all over the world from enjoying certain pleasures of which he does not approve. His miraculous power strikes first at female vanity, eliminating makeup, fancy hairdos, and fashionable clothing. The next targets are radio, television, and movies. The lack of entertainment for the jobless masses leads to chaos.

In Part Two, the radio host, one of the few people who know the reason for these sweeping changes, is forced to join a massive government project designed to investigate and solve the problem.

Forced, as in men with guns come to get him.

The guy manages to convince the authorities that the preacher is responsible. Meanwhile, almost all fiction and comic strips become unreadable, another sign of his power. (He leaves certain things alone, such as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Pogo, proving he has good taste.)

An example of a distorted text. I think it says something like He took aim right at her . . .. I can't read the last word.

Our hero visits the preacher's rural community, which proves to be almost entirely self-sufficient. He is reunited with the preacher's daughter, whom he met in Part One, and romance blooms.

Her real name is Sue, and she's got other secrets.

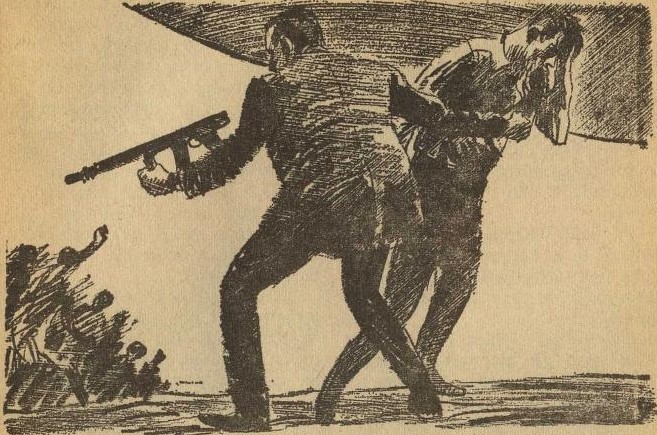

When the real story reaches the public, the radio host has to save the preacher from an angry mob, then work out a compromise with him. In return for undoing at least some of his miracles, he'll get the chance to broadcast his socioeconomic message to the world.

Rescuing his future father-in-law.

Beneath the surface of a semi-comic plot, the author deals with a lot of serious issues. He considers overproduction, excessive consumerism, waste of natural resources, automation, shallow media, lack of meaningful work, mob violence, authoritarianism, and a bunch of other things. It takes a special kind of skill to mix all this stuff into an entertaining novel.

A thoughtful four stars.

Feasting on the Fatted Calf

(That's just a metaphor. I don't eat meat.)

I'm delighted to see that I came back to write about an above-average issue of the magazine. Everything was worth reading, even if not all of it was outstanding. There was a welcome variety, from comedy to horror, with a large serving of satire. You can choose among the breezy style of Dickson, the savage bite of Kagan, and the elegance of Leiber, to name just a few. All in all, it made for a very pleasant homecoming.

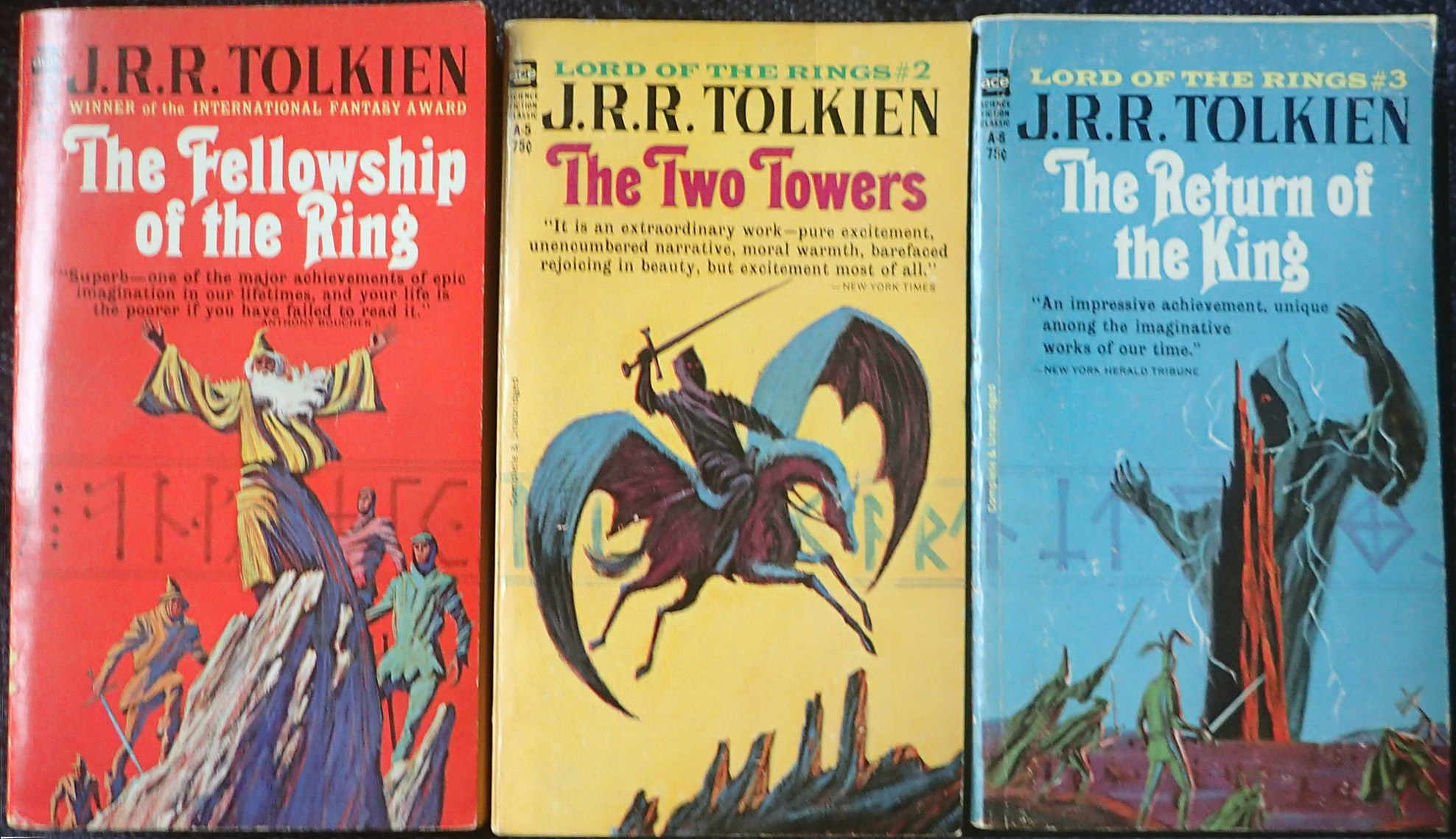

The first novel about Captain Horatio Hornblower. Good stuff.

![[July 18, 1965] The Prodigal Returneth (September 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n03_1965-09_0000-2-672x293.jpg)

![[July 16, 1965] To Fresh Woods (August 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650716cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 14, 1965] The New Dispensation (August 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/amz0865-cover-500x372.png)

![[July 12, 1965] A pair of Aces (July 1965 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650712covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 10, 1965] "Since I fell for you" (a Young Traveler's crush)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650710randall-480x372.jpg)

![[July 8, 1965] Saving the worst for first (August 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650708cover-521x372.jpg)

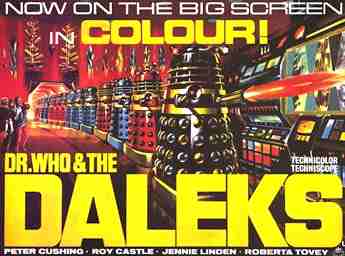

![[July 6, 1965] Same Difference (<i>Dr. Who And The Daleks</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650706daleks-672x372.jpg)

![[July 4, 1965]: Hoode Hoode Hoo (<i>Doctor Bloodmoney</i> by Philip K. Dick)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/dr-bloodmoney-600x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1965] Gallimaufry (August 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/IF-cover-1965-08-649x372.jpg)

![[June 30, 1965] Every Day has its Dog (July 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650630cover-672x372.jpg)