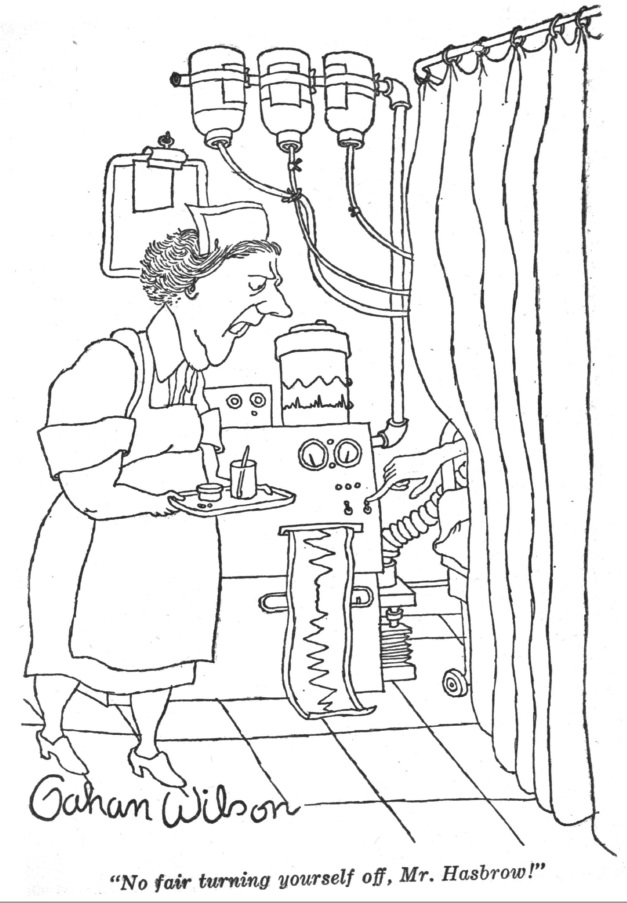

by Gideon Marcus

Royal Families

The news always likes to focus on heads of state, especially when they are flashy or glamorous in some way. From Princess Grace of Monaco to Crown Prince Akihito of Japan, these leaders are instant idols, somehow more compelling for having the reins (and reigns) of nations even though they presumably put their pants/skirts/obis on the same way as the common folk.

This week scored a triplet of spotlights. For instance, in the island nation of Tonga, Taufaʻahau Tupou IV was crowned monarch in a ceremony that included a feast of 71,000 suckling pigs! And that, by itself, tells you all you need to know about the current Jewish/Moslem population of Tonga…

Closer to home, El BJ, chief of the United States, has got his first grandson. Patrick Lyndon Nugent is the newborn child of First Daughter Luci Nugent (neé Johnson). There is no word, as yet, whether his toddler status will grant him deferment in the lastest draft lottery.

Finally, junta chairman General Nguyen Cao Ky, the flamboyant leader of South Vietnam since 1965, has decided not to run for President in the upcoming democratic (perhaps) September elections. Premier Thiệu has been backed by the junta for the top role, instead, with Ky getting the Vice Presidential nod. It's all a lot of musical chairs, anyway. After all, Ky has asserted that the only politician he admires is Hitler, which tells you all you need to know about the state of democracy in that country (and its current Jewish population…)

Watching Big Brother

Fred Pohl, one of the original Futurians and a pillar of the SF community, has had his hands full for nearly a decade. After he took over the reins of Galaxy and the newly acquired IF from H. L. Gold, rather than sit on his laurels, he looked for new worlds to conquer. Thus, Worlds of Tomorrow was launched in 1963. But juggling three mags (plus a few reprint-only titles) was a challenging job, often resulting in uneven quality and occasionally right-out flubs. For instance, last year's issue of Worlds of Tomorrow where the pages got all mixed up.

One would think, with WoT going out of publication, that things might be less hectic over at the Guinn Co. mags. But, in fact, this month's issue of Galaxy is even more higgledy-piggledy, making reading a real challenge.

by Sol Dember

Which is a shame, because there's some quite good stuff in here (mixed with some mediocre stuff, to be sure). Thankfully, you've got me to be your guide. Just grab your compass, or you might get lost.

Hawksbill Station, by Robert Silverberg

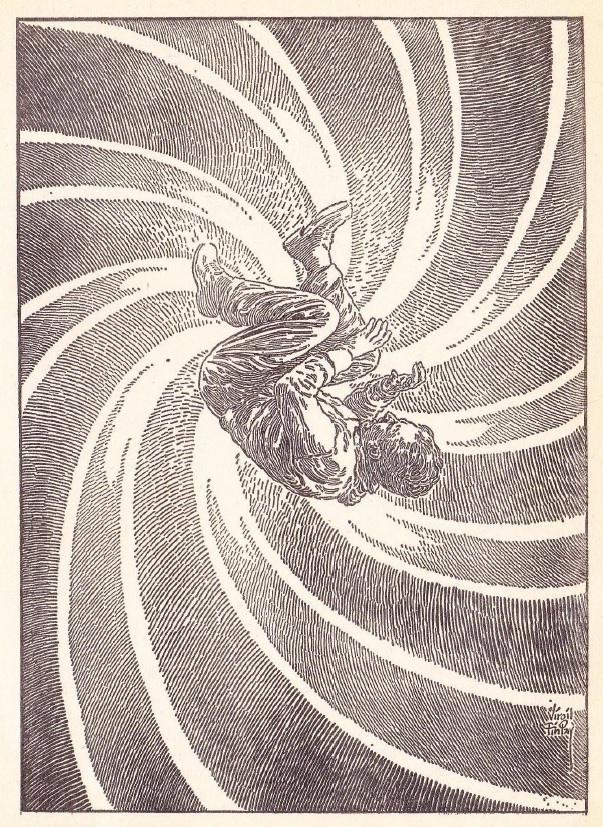

by Virgil Finlay

One-way time travel is developed in the early 21st Century. Since humanity is deathly afraid of creating paradoxes, the new portals are used by the totalitarian regime for just one purpose: shipping undesirables into the far past, a sort of Paleozoic Botany Bay.

Hawksbill Station is the one reserved for male subversives, established sometime in the late Cambrian (Silverberg repeatedly gives a date of two billion years ago, but of course, the Cambrian went from about 600-500 million B.C.) Our perspective is that of Barrett, the de facto head of the more than 100 settler/prisoners on the coast of what will one day be the Atlantic Ocean. It is a community slowly decaying as its denizens age along with no greater purpose in life. That is, until a new young convict arrives from the future, one who appears to be a government spy…

This is more of a travelogue than a story, and the ending comes on a bit abruptly. But the characterization, the details, the setting are all so gripping that I tore through the novella in no time, despite the labyrinthine page distribution.

Four stars, and if it ever gets expanded into a novel, it could make five.

Angel, Dark Angel, by Roger Zelazny

In another future-set tale, society is maintained by a sort of corporate Angel of Death who, with the help of ten thousand teleporting assistants, brings death to citizens after they have made sufficient contribution to humanity (and are, perhaps, on the verge of being detrimental).

One noteworthy woman has cultivated the aesthetic race of spirules (depicted on the cover) as an antidote to the cold, mechanistic technology of her time. A subordinate angel is sent to dispatch her, but things prove more complicated.

This is a middlin' Zelazny story, not an empty poetic suit like some, but not a near masterpiece like some of his other works. Three stars.

We're Coming Through the Window, by K. M. O'donnell

Throwaway vignette about a fellow who keeps duplicating himself due to time travel and needs Fred Pohl's help to get out of it.

Cute. Three stars.

Ginny Wrapped in the Sun, by R. A. Lafferty

Ginny seems to be a precocious four year old, but in fact, is actually just a baseline human, maturing at age 4 and going on as an upright monkey. It's the rest of us who are evolutionary aberrations, having five times as many heartbeats that a creature our mass should have. Inevitably, Lafferty suggests, we'll all go ape.

This tale doesn't really work, and it's a bit more impenetrable than Lafferty's usual fare. Two stars.

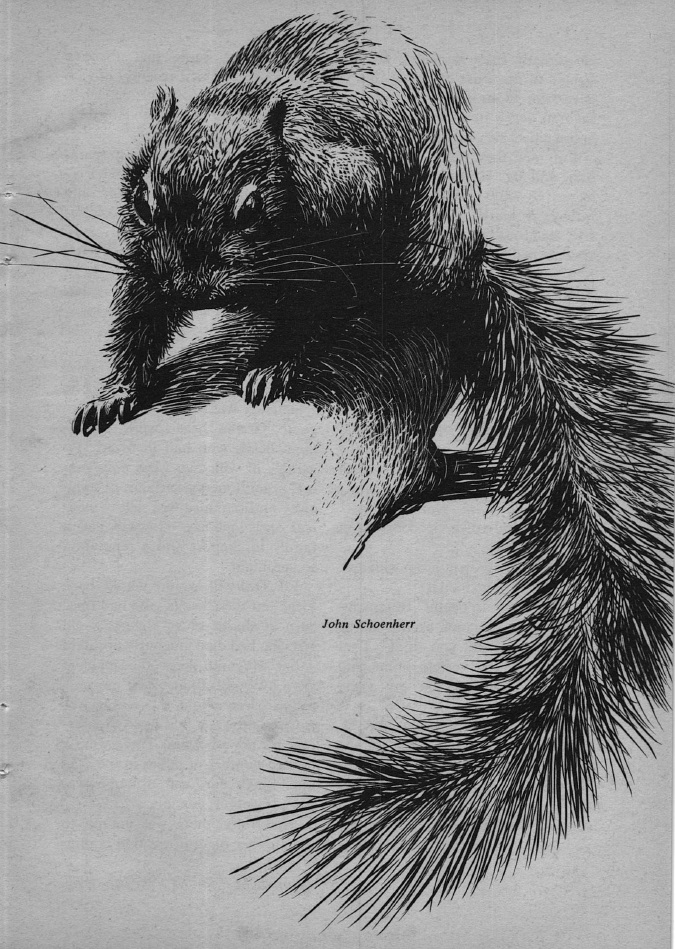

For Your Information: A Pangolin Is a Pangolin, by Willy Ley

Ley's article on the strange mammal that is neither aardvark nor anteater nor armadillo is interesting, but not much more than you might get from a rather good encyclopedia entry.

Three stars.

9-9-99, by Richard Wilson

Two wizened old characters are determined to settle an old score since both have outlived their wagered death dates, the bet having been made back in the 30s.

Whether it is even possible for them to collect given the state of the Earth in the late '90s is another matter…

Good enough, I guess. Three stars.

by Wally Wood

Travelers Guide to Megahouston, by H. H. Hollis

by Wally Wood

This is a very long, somewhat farcical account of a 21st Century evolution of the Astrodome, in which domes enclose whole cities.

Pretty dull stuff. Two stars.

The Being in the Tank, by Theodore L. Thomas

An alien being materializes in the heart of a hellish hydrazine factory and demands to speak to the President. But is he the real deal?

Forgettable, but inoffensive. A low three stars.

Hide and Seek, by Linda Marlowe

A childhood game is adapted into a method of population control. It has shock value, but little else.

Two stars.

The Great Stupids, by Miriam Allen deFord

Mad scientist makes everyone under 50 a mental moron, all in service of a rather lame joke at the end. DeFord was once one of the stars of the genre, but her light has waned over the years. Here's hoping she's a Cepheid variable and not a dying dwarf.

To Outlive Eternity (Part 2 of 2), by Poul Anderson

by Jack Gaughan

It is fitting that the final long piece of the issue is a sort of mirror image of Silverberg's novella in terms of strengths and weaknesses. As we read in last month's installment, the ramscoop colony ship Leonora Christine suffered damage to its decelerators while traveling at near light speed on the way to Beta Virginis. The solution: to accelerate to terrific velocities instead, plunging through the heart of the galaxy and out into the comparative emptiness of intergalactic space where repairs might be effected.

In this half, event after event conspires to force the Christine to travel ever faster and faster, ultimately spanning the lifespan of the universe and beyond in a matter of months. The story is told as a series of problem-solving conversations spread out over the weeks, and each character largely exists solely to have these conversations. Except for the women, of course, who are almost universally hysterics or hangers-on…except for the First Officer who ultimately whores herself out for the good of the crew.

In short, the setup and ideas are really neat, but its a plot outline, not a novel. And where Poul Anderson does try to characterize, it's with quick stereotypes, and usually not agreeable ones. As for setting, there really isn't one. The crew of the Christine might as well be floating heads in blank spaces for all we really get to experience the ship.

Readable, but badly flawed. Three stars.

Matrix Goose, by Jack Sharkey

Last up, some very familiar nursery rhymes as they might be rendered by robots–after the demise of humanity. It's cute. Three stars.

Perhaps my favorite example, art by Gray Morrow

Cross-eyed Kin

And so, Galaxy ends up a largely enjoyable, but unremarkable read — just under 3 stars in ranking. Perhaps, with the demise of Worlds of Tomorrow further in the rear-view mirror, Pohl will be able to concentrate on (and concentrate the best stories into) his remaining mags.

On the other hand, perhaps he hasn't learned his lesson. He's got a new magazine is coming out next month…

![[July 8, 1967] Family lines (August 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670710cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 6, 1967] Humour, British-style (<i>Carry on Screaming</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670706poster-672x372.jpg)

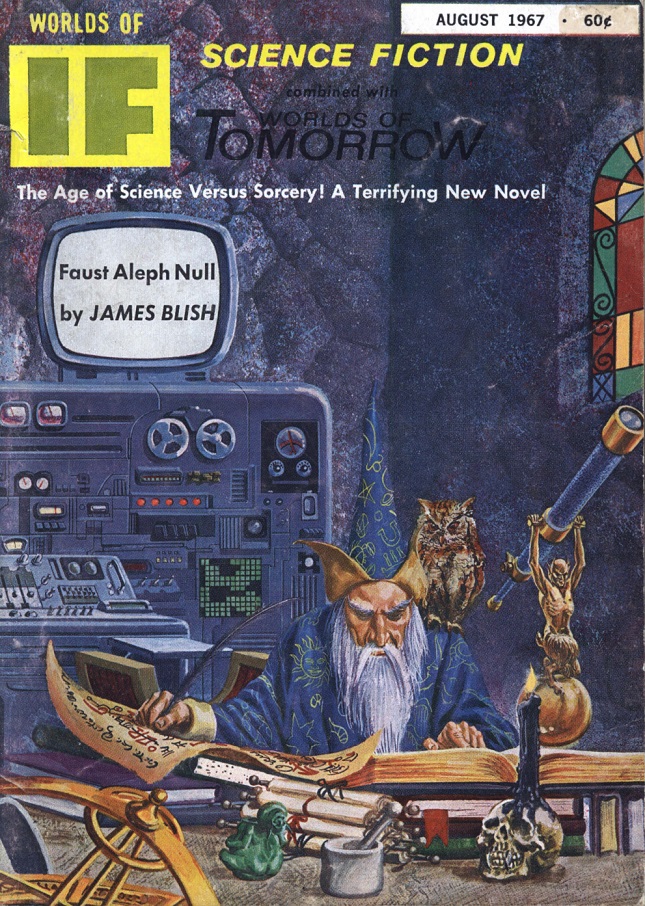

![[July 4, 1967] Angels and Demons (August 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/IF-1967-08-Cover-645x372.jpg)

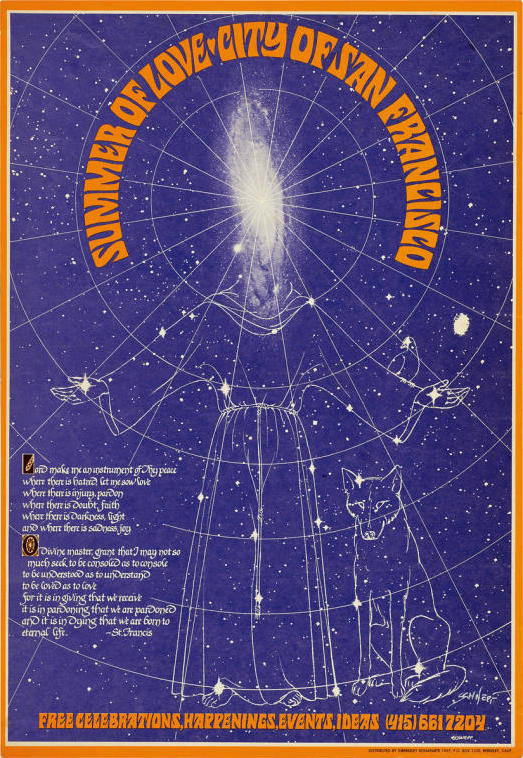

The official poster created by Bob Schnepf

The official poster created by Bob Schnepf The festival was delayed one week due to bad weather.

The festival was delayed one week due to bad weather. This poster is a good example of the new psychedelic art style.

This poster is a good example of the new psychedelic art style. Hippie Randall DeLeon greets the sun and makes the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle.

Hippie Randall DeLeon greets the sun and makes the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle. That’s not quite how black magic works in the new Blish novel, but it ought to be. Art by Morrow

That’s not quite how black magic works in the new Blish novel, but it ought to be. Art by Morrow![[July 2, 1967] An Explosive Ending (<i>Doctor Who</i>: THE EVIL OF THE DALEKS [Part 2])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670702emperor-672x372.jpg)

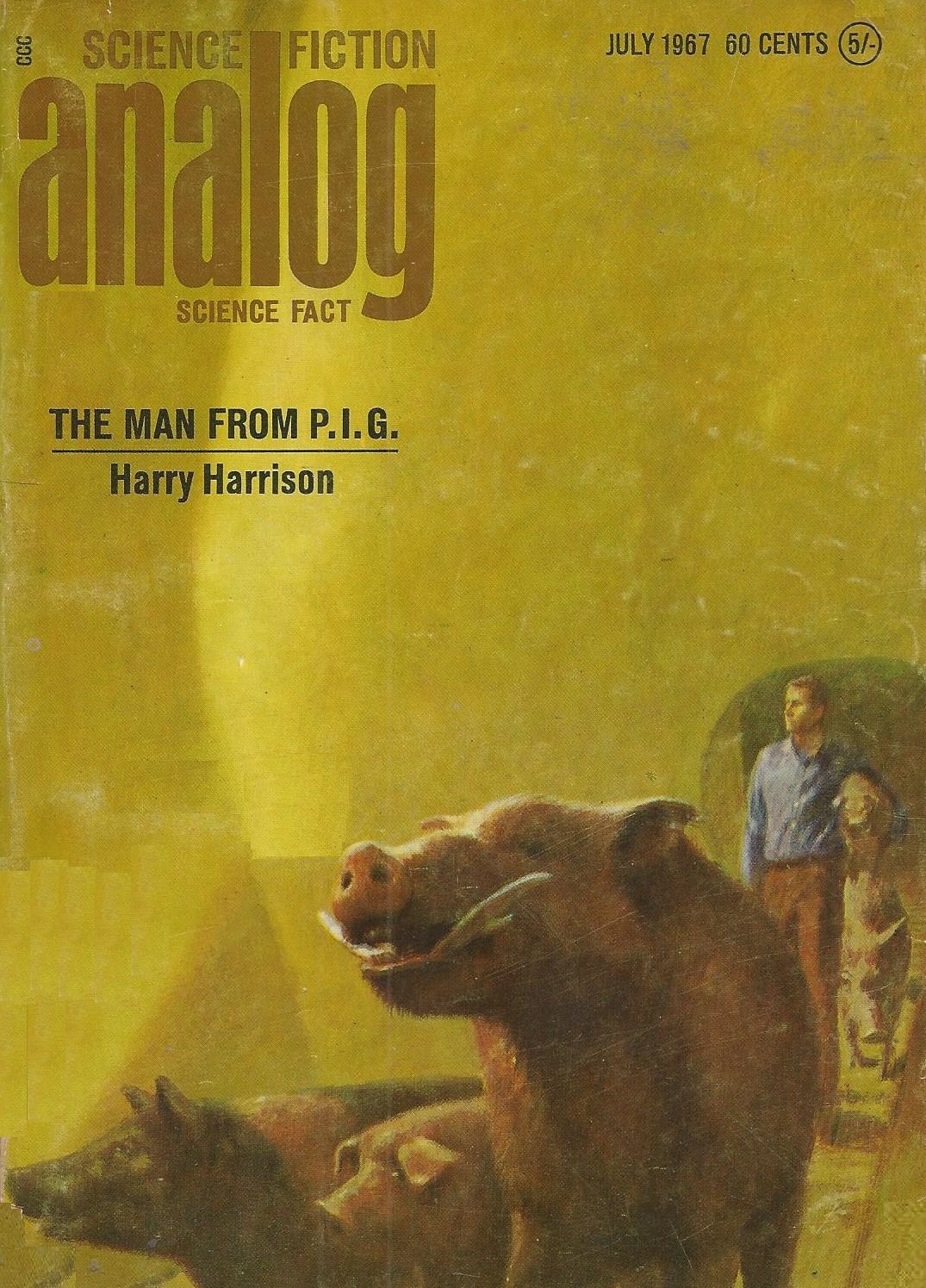

![[June 30, 1967] Bad trip (July 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670630cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 28, 1967] Around the World in Two Seconds (<i>Our World</i> Global Satellite Broadcast)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Our-World-1.png)

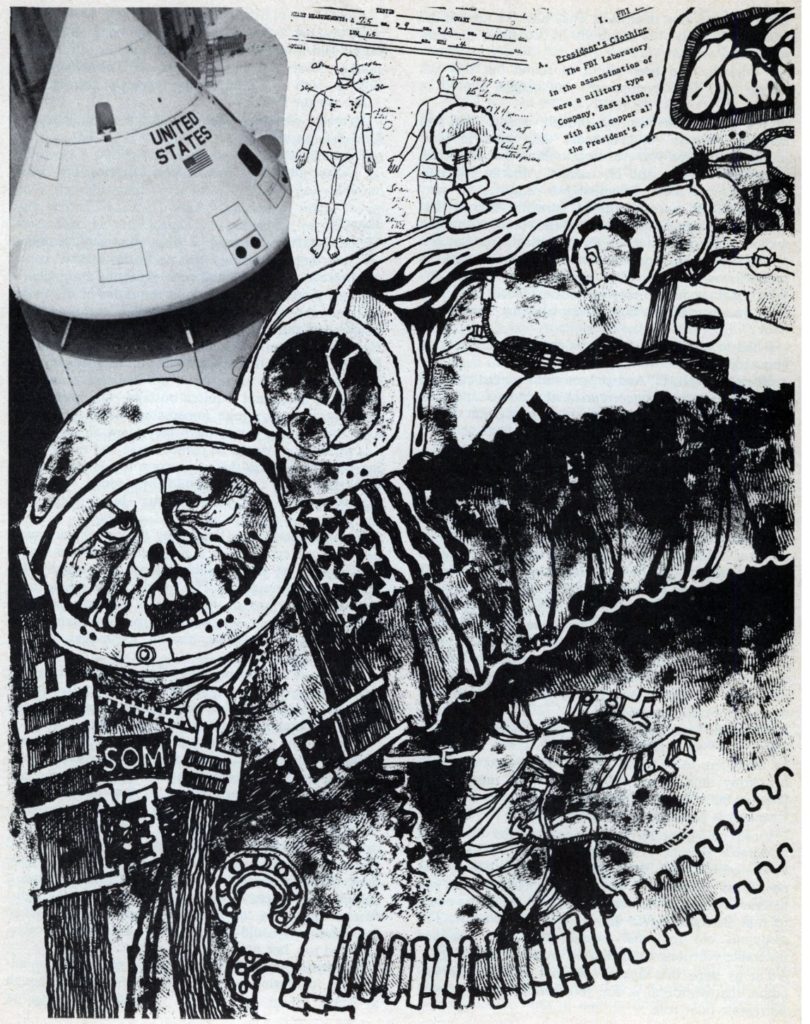

![[June 26, 1967] Change is Here (<i>New Worlds</i>, July 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/New-Worlds-cover-July-1967-672x372.jpg)

Illustration by Zoline

Illustration by Zoline

![[June 24, 1967] Oh no, not again! (The James Bond movie, <i>You Only Live Twice</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670624poster-600x372.jpg)

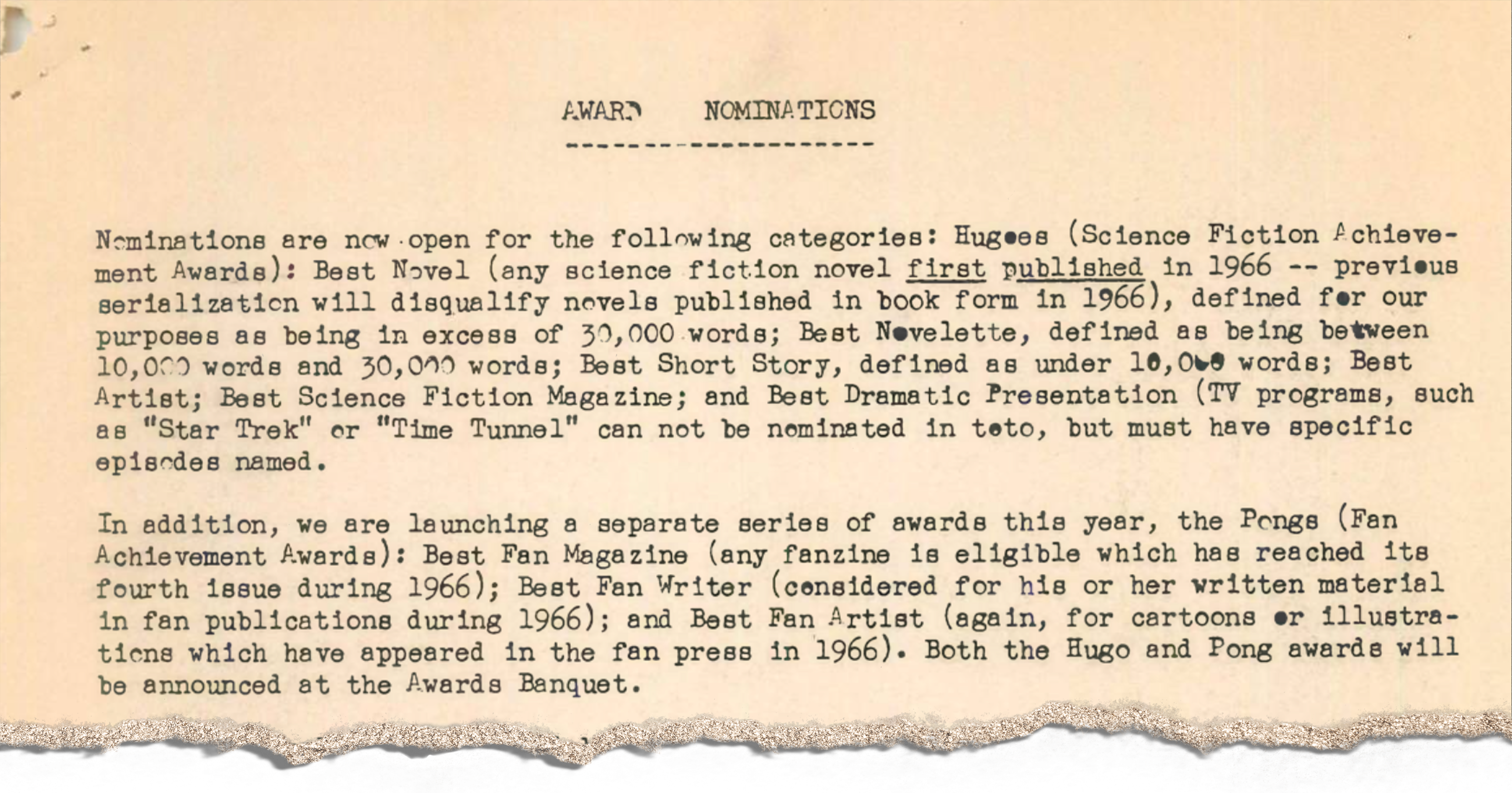

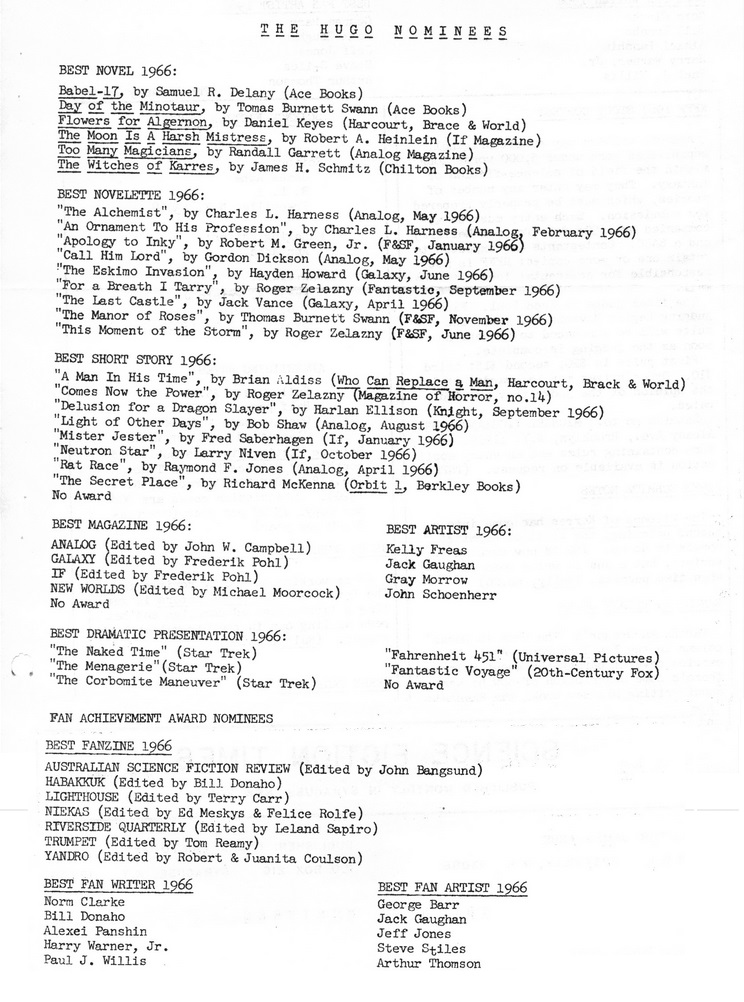

![[June 22, 1967] The Pong Arising from the World Convention](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670622hugos-672x372.png)

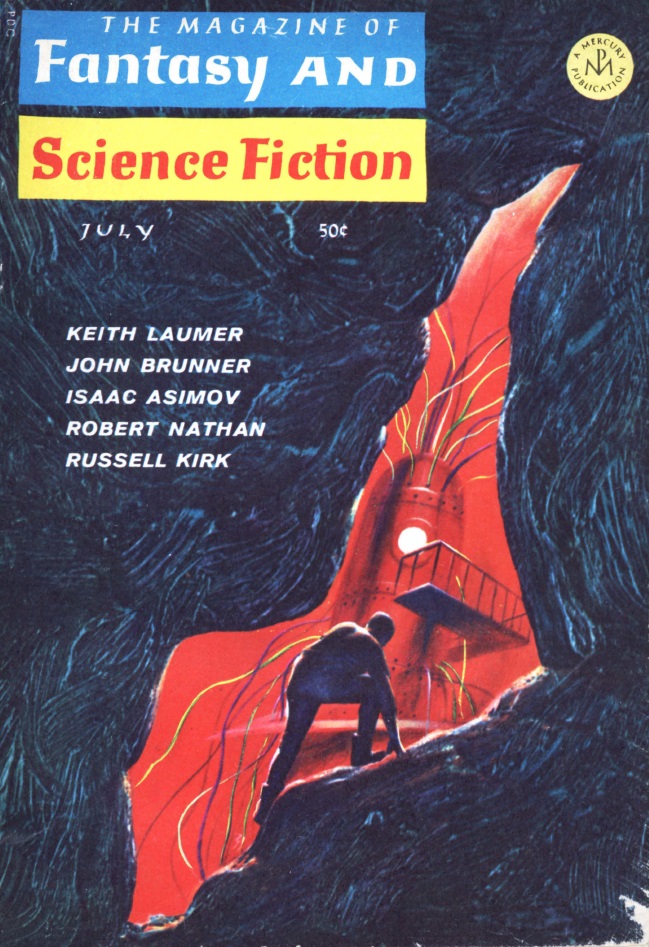

![[June 20, 1967] Yours sincerely, wasting away (July 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/670620cover-649x372.jpg)