Such stuff as dreams are made of

by Joe Reid

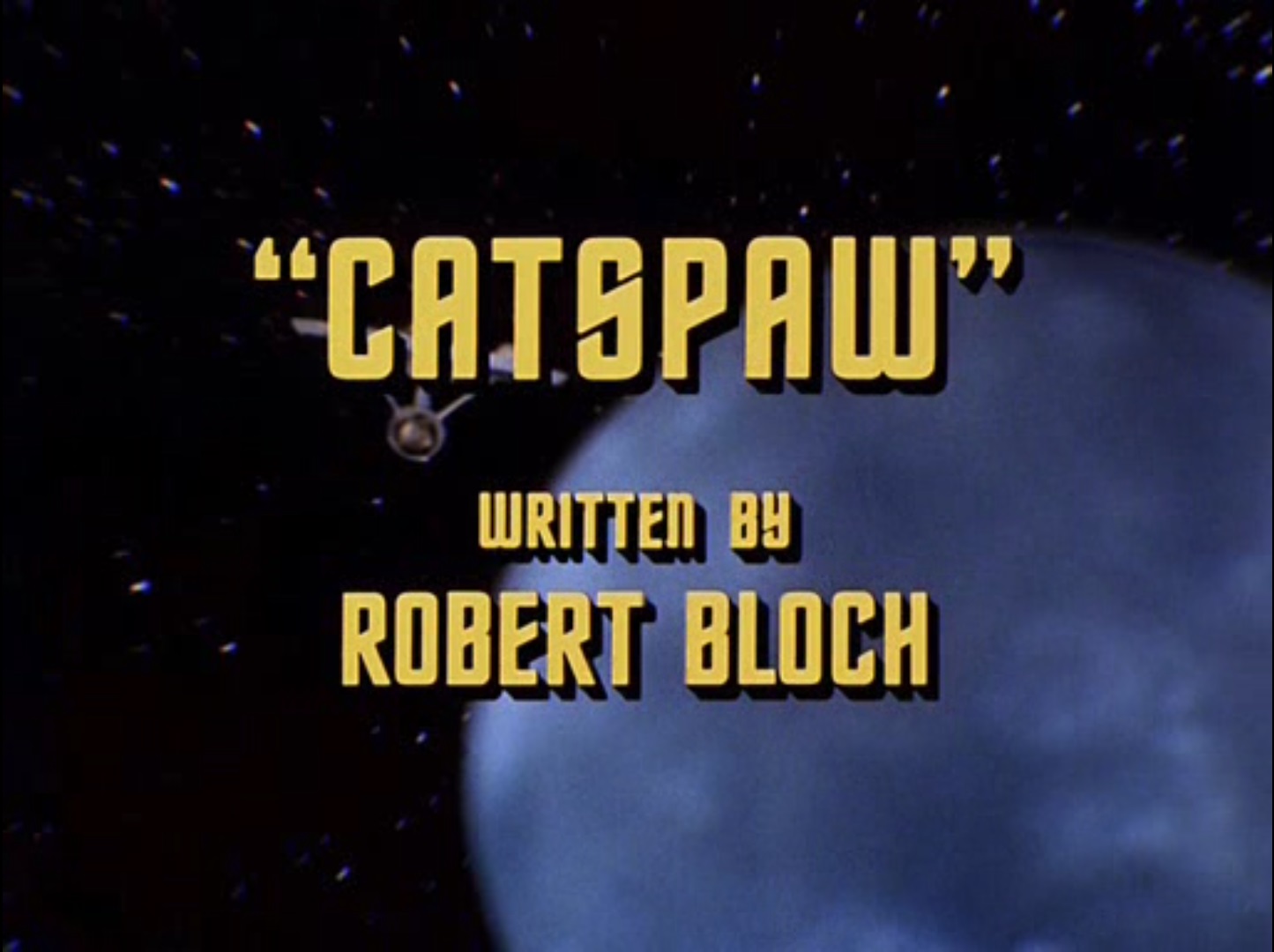

For the first several episodes, this second season of Star Trek was solidly impressive. We got to attend a Vulcan wedding. We saw a mythological deity from human antiquity in a sci-fi setting. We saw a transistorized deity faced and defeated. Then a dark alternate universe, followed by a giant cornucopia of doom! I regret that I must mention the episode with the red colored rock lizard worshippers, since that was undoubtedly the low point of this season. Sadly, this week’s episode, titled “Catspaw” comes very close to hitting the low that “The Apple” achieved.

Dear readers, in my opinion, futuristic sci-fi shows should avoid doing holiday themed episodes. I have no desire to watch sci-fi episodes about Christmas or Thanksgiving. Nor Easter, the 4th of July, Passover, Saint Patrick’s Day, or Columbus Day. So, watching what clearly stood out as "made for Halloween" was disappointing. Especially since I do not feel that the episode was served by the inclusion of said theme.

We started this seventh episode of the second season on the bridge of the Enterprise as our heroes awaited a report from the landing party composed of Scotty, Sulu, and a Crewman Jackson. A message came in from Jackson, with no word about the others. As Jackson beamed up to the ship, he arrived on the transport circle dead on arrival. Then from the non-moving mouth of the dead man came a ghostly warning to leave the planets and that the Enterprise was cursed.

"There is a curse on you! Also, you've left the oven on"!

Determined to find out the fates of Scotty and Sulu, Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, and Dr. McCoy beam down to the planet to find their people. Arriving on the surface they find that it was a dark and foggy night. What comes next, I was not expecting: As the trio begin their search, they are confronted by three ugly witch apparitions, and wouldn’t you know it they have a poem to share. “Winds shall rise, and fog descend, so leave here all, or meet your end.” Poetry so bad that it even garners a negative review from Spock.

"Hail Captain Kirk, Thane of Cawdor!"

If that isn’t a blatant enough holiday reference, Kirk and the others soon find themselves at a dark and eerie castle. Upon entering they are startled by a black cat which leads Kirk to make the first explicit Halloween reference of the night about trick or treat. They follow the cat hoping to see where it would lead them only to be knocked unconscious as the floor collapsed below their feet.

"There's my litter box!"

They awaken to find themselves chained to the walls of a dungeon next to a skeleton that looks exactly like what it is: a Halloween decoration, or maybe a model skeleton from my kid’s science classroom. As the doors to their cell open, we get our first looks at Scotty and Sulu as they enter the dungeon. Both are under some sort of magic spell and can’t speak but make it clear that they will take Kirk and the others to the people in charge.

I hope they weren't paid by the line for this one…

They meet two aliens that have taken the forms of a wand-sporting wizard named Korob, and the beautiful witch, Sylvia. Kirk, Spock, and McCoy find themselves at the mercy of powers that could endanger the Enterprise in orbit, conjure items out of thin air, and mind control their crewmembers.

Korob and Sylvia–a tale of two coiffures

It is here that the spooky themes began to subside as the magicians reveal themselves as truly alien, with little understanding of humans or even having physical bodies. They need humans and our minds to allow them more of the new experiences that they had created. An interesting premise, but since this is Halloween, it is drowned in hocus pocus.

In the end, Kirk is able to learn about and destroy the magic wand…er…transmuter, the item that allowed their powers to work. The defeated aliens returned to their original forms and promptly die. The conclusion of the episode comes fast with virtually no transition, save for a brief explanation from Kirk to his newly liberated crew.

"The missing pages of the script are right there."

Outside of the unnecessary holiday theme, this episode managed to stay true to the elements of what makes Star Trek good. The characters' behaviors were consistent with what we have come to expect. Kirk was smart and brave. Spock was insightful, and others, so long as they were not mind controlled, behaved as they should. Also the aliens had actual, explained reasons for their actions. All this combined made this episode passable and not the absolute debacle that “The Apple” was.

3 stars.

A fool thinks himself to be wise

by Janice L. Newman

It wasn’t a surprise to learn that the same author who wrote "What Are Little Girls Made Of?", one of the worst episodes of the first season, also wrote "Catspaw". Robert Bloch is famous for his horror writing, particularly the movie Psycho. But his horror fantasy scripts simply do not translate well to the grounded science fiction of Star Trek.

"Catspaw" was a frustrating experience. Not just because it didn’t feel at all like a Star Trek episode (and naysayers in the fanzines will no doubt comment, as they did with "Miri" in the first season, that they happened to catch this episode and weren’t impressed), but also because it had the potential to be an interesting episode but simply couldn’t make it work.

Firstly, the idea that the ‘collective unconscious fears’ of our species would be reflected in a gothic castle, Shakespearian witches, and black cats, is simply ridiculous. If there is some kind of collective unconscious for humanity, the reflection of it must necessarily be both much more chaotic and universal to the human experience. This flaw could have been overcome either by saying that the aliens drew their ideas of us from our popular culture, or perhaps that they drew on one particular crewmember’s unconscious fears. Alternatively, rather than using the traditional gothic symbolism, the show could have tried something more innovative, imagining what might frighten any human anywhere throughout all of history.

Another flaw was the pacing. The scene of Sulu unlocking everyone’s chains took far too long, for example, while the final scene felt rushed. The scenes on the bridge were dull, especially with the wooden DeSalle in charge.

"I am acting!"

A particularly annoying problem with the episode was that it set up situations to be resolved and then didn’t follow through. The most egregious example of this occurs when the bridge crew finally manage to ‘dent’ the forcefield around them—only to have the forcefield lifted by one of the aliens before they can escape it on their own. While I would have been mildly irritated at the similarity to "Who Mourns for Adonais?" if the crew had cleverly managed to escape, I was far more irritated that the crew was set up to escape and then not given the opportunity to do. What was the point of those scenes on the bridge, then?

The ‘horrific’ aspects to the story often came across as comedic instead. Perhaps the ugly witches might scare a young child watching the show, but the room full of adults I was watching with chuckled at their appearance and their sung proclamations. One of the saddest pieces of wasted potential was the aliens’ true appearance. They looked like little birds made of pipe cleaners, and when they came on the screen they got the loudest laugh of the evening. A scene which could have and should have been poignant or grotesque was again turned comedic by poor writing, pacing, and framing.

I’m torn as to what rating to give this episode. On one hand, it didn’t even feel like an episode of Star Trek. On the other, there were some interesting elements, and it wasn’t confusing like "The Alternative Factor" or dully exasperating like "The Apple". Plus, there was a cat. Still, when all is said and done, the wince-inducing scenes between Kirk and the Sorceress canceled out what good there could have been. I can’t give it more than one star.

Signifying Nothing

by Amber Dubin

It's ironic that this episode is called "catspaw" because the plot is about as cohesive as a heavily pawed ball of yarn; a tangle of threads that don't hold together or go anywhere.

The acting quality of the episode peaks early with the deeply convincing collapse of ensign Jackson off the transporter pad. Yet the fact that he is the only non-essential crewman sent down to this clearly hostile planet makes less than no sense. Continuing the madness, after Jackson's corpse is used to deliver a message of warning that's immediately ignored, Kirk, Spock and McCoy are subjected to another gratuitous display from disembodied witch heads spouting Shakespearian-esque poetry. You would think this theme of theater-obsessed eccentric illusion-projectors would continue, but you would be wrong, as the only further theatrical implications come in the form of the heavily made up and costumed Korob, whose appearance is given no explanation.

Though you must admit: the camera loves him!

In further defiance of explanation, the crew wakes up chained to the walls of a dungeon after the floor of the castle they enter haphazardly collapses beneath them. Next ensues an absolutely mystifying scene where a zombified Sulu painstakingly unlocks their restraints cuff by cuff. This gesture is immediately made unnecessary when they are teleported into a throne room with Korob, one of their captors. As we've seen in "Squire of Gothos" or "Who Mourns for Adonais?" Korob reveals himself to be overpowered alien attempting to understand the nature of man. He doesn't get too far in his speech, however, before he is upstaged by the real star of the play, the necklace-wearing black cat that transforms into Sylvia, a beautiful woman.

I was hoping Sylvia's introduction would lead to a McCoy-centered episode, as Bones seems to be unable to take his eyes off her.. necklace.. from the moment she enters. That theory is immediately banished as they are all teleported back to the dungeon and McCoy re-enters as a zombie (a role to which he is well-suited). The task of seducing the femme-fatale then predictably falls on Kirk, who delivers his clunkiest and least believable performance in the series so far as he outright fails in his attempt to make her feel too pretty to harm them any longer.

Despite this entirely nonsensical plot, somehow the biggest disappointment of the episode is yet to come as the aliens descend into madness. Korob is killed by a giant door, which is as easily avoidable as it is imaginary, making it therefore harmless to a being capable of casting such illusions. Even more absurdly, these magical beings, who are said to be powerful conjurors with no abilities of sensory perception, are suddenly revealed to resemble tiny, delicate bundles of exposed nerves.

Jim Henson presents: rejected muppets!

The episode abruptly ends, nothing is resolved, no one understands anything better and I'm baffled by the fact that a simple framing device of a crewman explaining Halloween to Spock at the beginning of the episode could have cleared up where these aliens got material for all the imagery in the episode. Instead, we spent more time watching Sulu unlock imaginary restraints than we do deciphering the nature or motivations of crusty blue pipe-cleaner puppet-gods.

Ridiculous. Two stars.

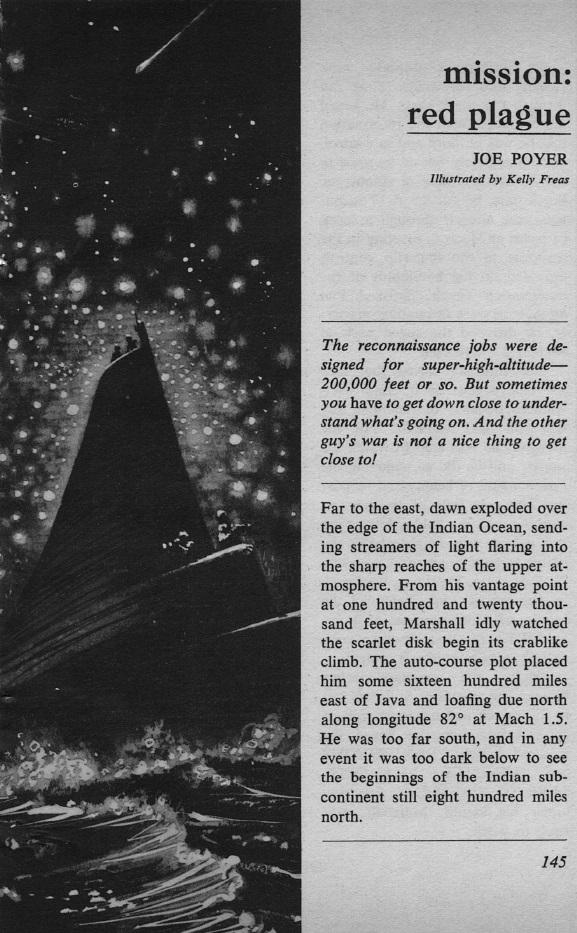

by Gideon Marcus

The Play's the Thing

I must confess–I did not hate this episode. Not because it was good; heavens no! It wasn't even Star Trek. Just our favorite characters having a Halloween lark. In fact, in my mind, I've completely disregarded it as a Star Trek episode. Just as Spock and Uhura sometimes jam together in the lounge (why haven't we seen that this season?), and just as Kirk insists that real turkey be served on Thanksgiving, I've concluded that it is an Enterprise tradition that Halloween is celebrated with a big todo.

I can see Sylvia actually being Lt. McGivers' replacement, and with a minor in theatrics. Once aboard the Enterprise, she began penning her magnum opus: a play involving all of the senior officers of the ship. Suddenly, all the nonsensical bits make sense. The beaming down of Scotty and Sulu as a landing party, the spooky settings and effects, the endless kissing scenes ("Oh, but Captain, these are vital to the plot! Really, it won't breach protocol at all…")

"Did I hear a door slam? Darn. We'll have to do the whole take over!"

Taken as such, suddenly the episode is palatable. It does move pretty well. Theo Marcuse is always a delight (and a genuine war hero, and he has a great last name; he's probably my cousin). The score was nifty, particularly in the fight scene. Less so in the five minute bit when Sulu unlocked Kirk's fetters.

And there was abundant display of a cat. That, alone, is worth a star.

So, again, "Catspaw" isn't a good episode. But I would watch it in reruns three times before I suffered through "The Apple" again…

Two stars.

Something Wicked this way Comes

by Jessica Dickinson Goodman

I rather enjoyed this episode. As Amber said, it wasn't good. But it was fun. Maybe it's because I enjoy camp. I liked Theo Marcuse's silks and jewels and perfectly shaved eyebrows. I liked the kitschy sets – perhaps borrowed from a recent vampire flick? – and as other writers have noted, the cat was a special treat.

I was less impressed by how many of the so-called ‘collective unconscious fears' involved woman-hating. Crones and seductresses, liars and cheats, the non-crewwomen in this episode were like something from Jesse Helms' fever dreams, no collective I'm a part of.

Janice's proposition that the episode would have been better if it had featured truly universal fears sparks my imagination far more than anything in the episode itself. What truly scares everyone? In a world with apocalypse-worshiping churchgoers, can we say everyone is afraid of death? I would say that many, many of us are afraid of a nuclear attack from our friends across the Bering Strait, but people living outside of the blast zones could be reasonably excused from the universality of that fear.

Stepping away from the philosophical mindtwister Janice gives us and back to this rather silly episode, I am looking forward to seeing this one in reruns. There's just something so fun about our heroes getting tied up – several times – like maidens in a gothic novel.

I think the Captain is starting to enjoy it…

Watching Captain Kirk once again try to kiss his way out of trouble was made all the more fun when his captor/target caught him at his game and refused to play anymore. Despite Sylvia's embodiment of a mushy handful of cruel gender stereotypes, I found myself enjoying her time on screen more than almost anyone aside from the core cast. Cheers to Antoinette Bower for taking a two-dimensional role and turning it into something fun and memorable.

There were many, many, many ways this episode could have been improved. I would be disappointed if next week's episode shared in the same nasty stereotypes of women. I fear it will, as it centers on one of my least favorite characters in this series, Mr. Mudd.

Perhaps Sylvia will make a guest appearance and turn him into a toad before he hurts more women.

Three stars.

I don't know how likely it is that Mudd will get his comeuppance, but we can certainly hope!

The episode airs tomorrow night. Here's the invitation! Come join us.

Also, copies of The Tricorder are still available — drop us a line for details!

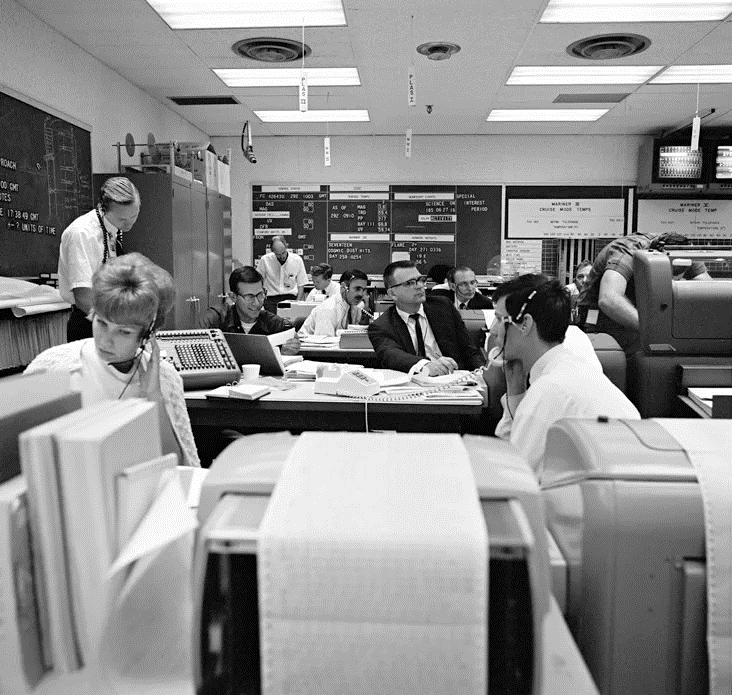

![[November 2, 1967] Trouble and Toil (<i>Star Trek</i>: Catspaw)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671102title-672x372.jpg)

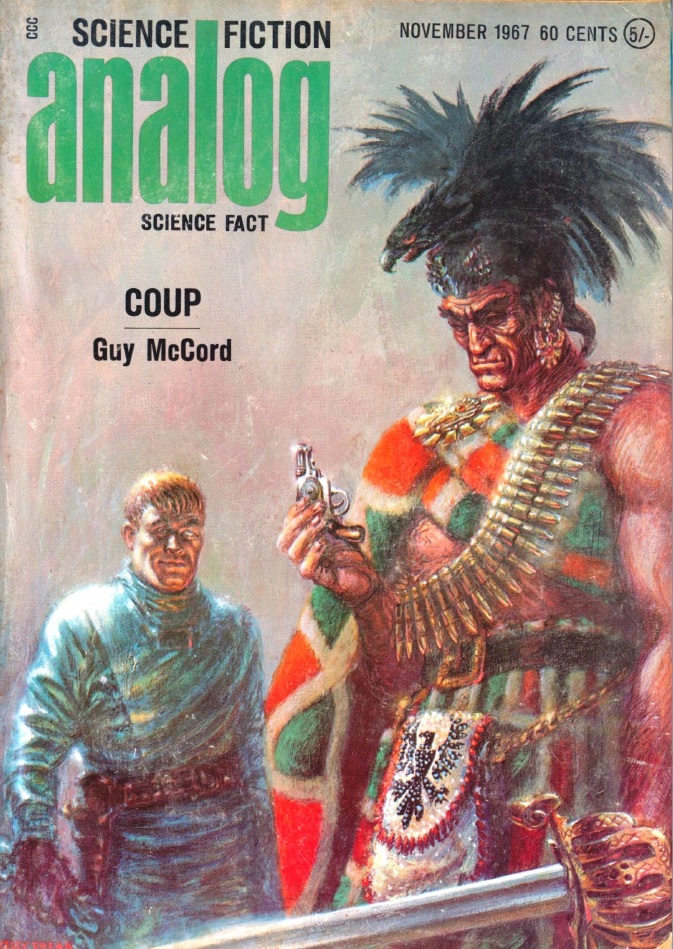

![[October 31, 1967] Same ol' (November 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671031cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 28, 1967] Unveiling Venus – at Least a Little (Venera-4 and Mariner-5)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Venus-desert.png)

![[October 26, 1967] Duet in G(ray) (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Doomsday Machine")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671026title-672x372.jpg)

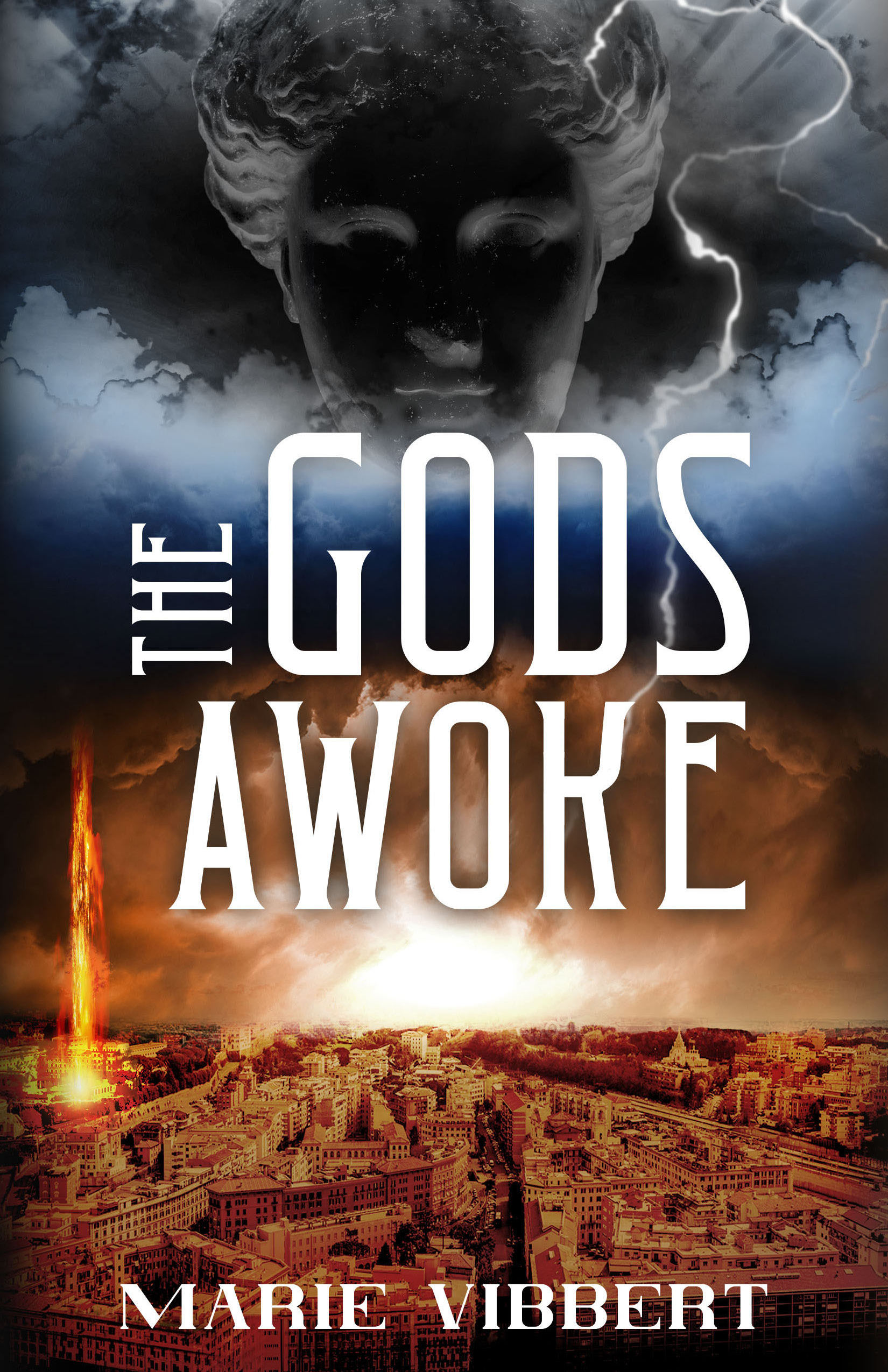

![[October 24, 1967] War, Anti-utopias and Near-Future Apocalypses <i>New Worlds</i>, November 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/New-Worlds-November-1967-672x372.jpg)

Cover by Vivienne Young

Cover by Vivienne Young An example of the logic shown in this article. Not sure I understood this!

An example of the logic shown in this article. Not sure I understood this!

Example of Self's imagery.

Example of Self's imagery. Uncredited image, but it looks like a Douthwaite, who is credited in the magazine.

Uncredited image, but it looks like a Douthwaite, who is credited in the magazine. Another uncredited image that looks like a Douthwaite.

Another uncredited image that looks like a Douthwaite. Sharing the horror in full – another poetic gem – well, they seem to be liked by some!

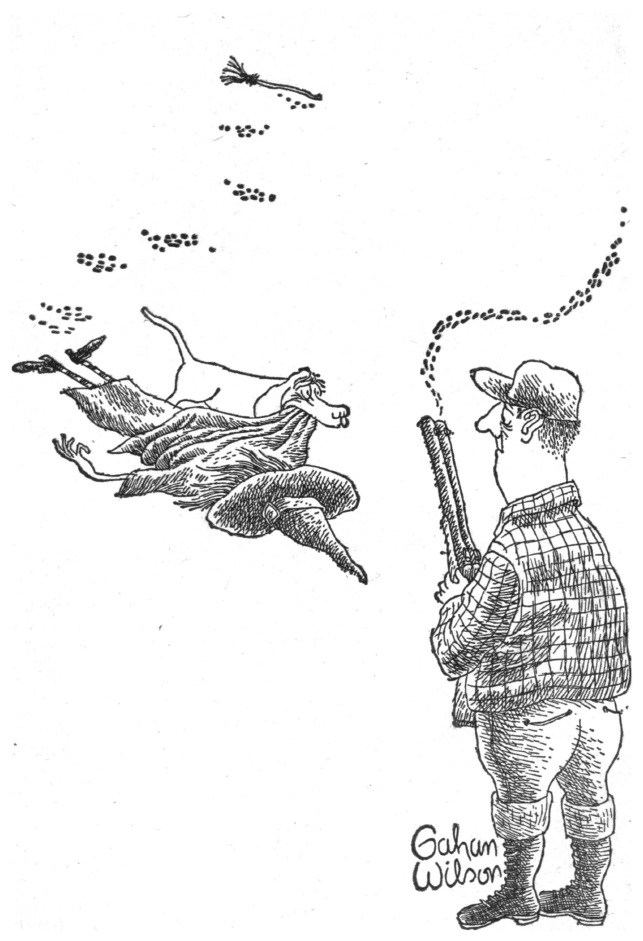

Sharing the horror in full – another poetic gem – well, they seem to be liked by some! Illustration by Cawthorn

Illustration by Cawthorn The future of energy?

The future of energy?

An advertisement from this month's magazine that shows how different book sales and New Worlds magazine is, perhaps? How many of these authors are mentioned in detail in the magazine these days?

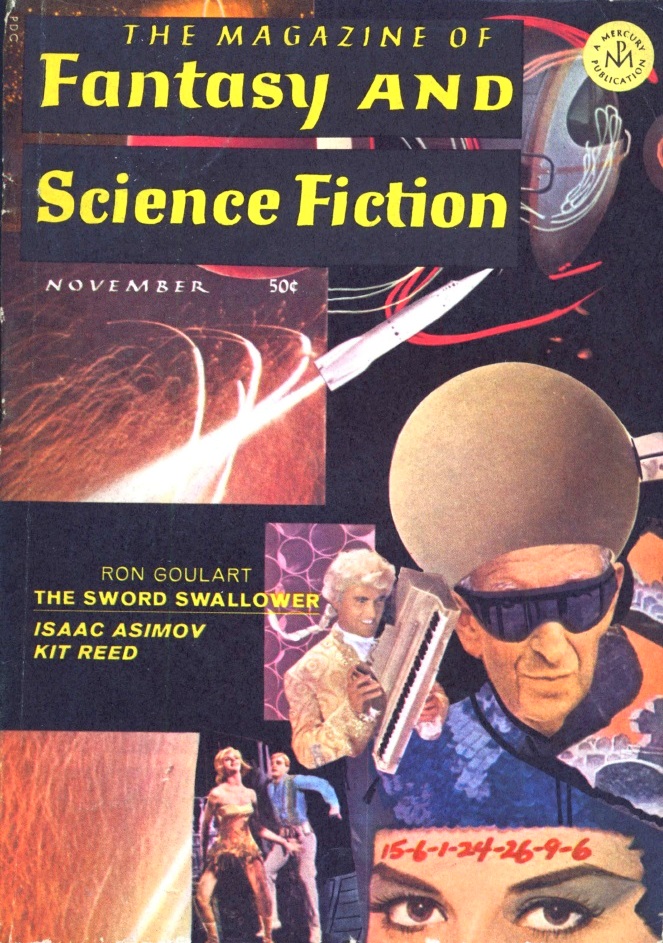

An advertisement from this month's magazine that shows how different book sales and New Worlds magazine is, perhaps? How many of these authors are mentioned in detail in the magazine these days?![[October 22, 1967] Equal Opportunity Employer (November 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671022cover-663x372.jpg)

![[October 20, 1967] Spoils the Bunch (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Apple")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671020title-672x372.jpg)

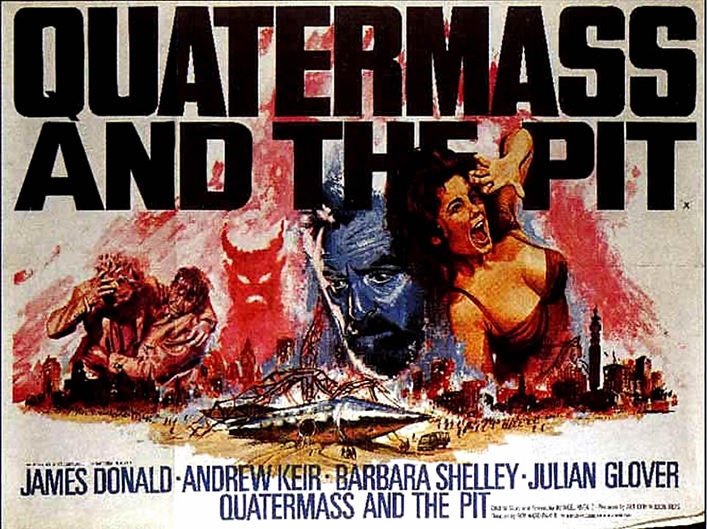

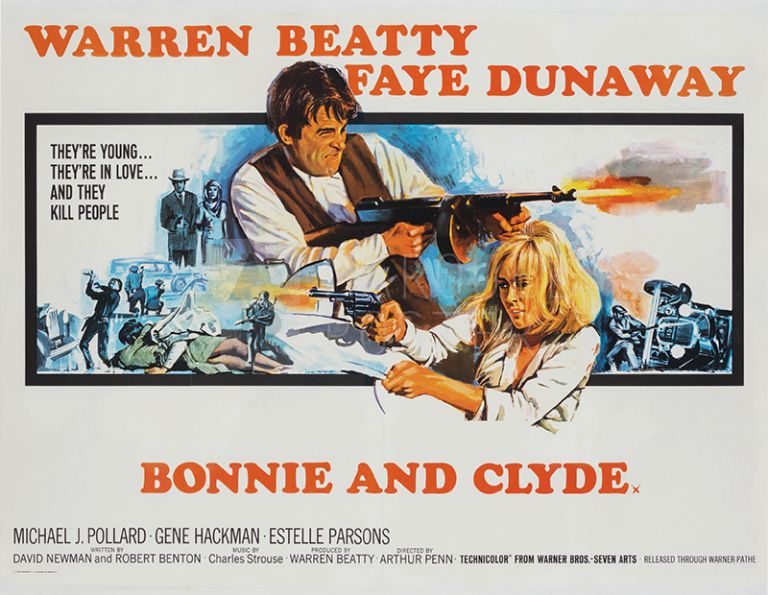

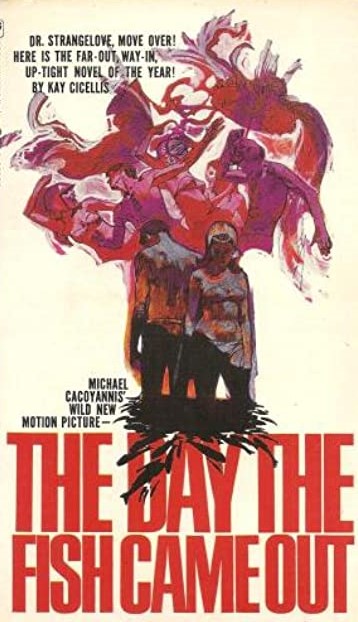

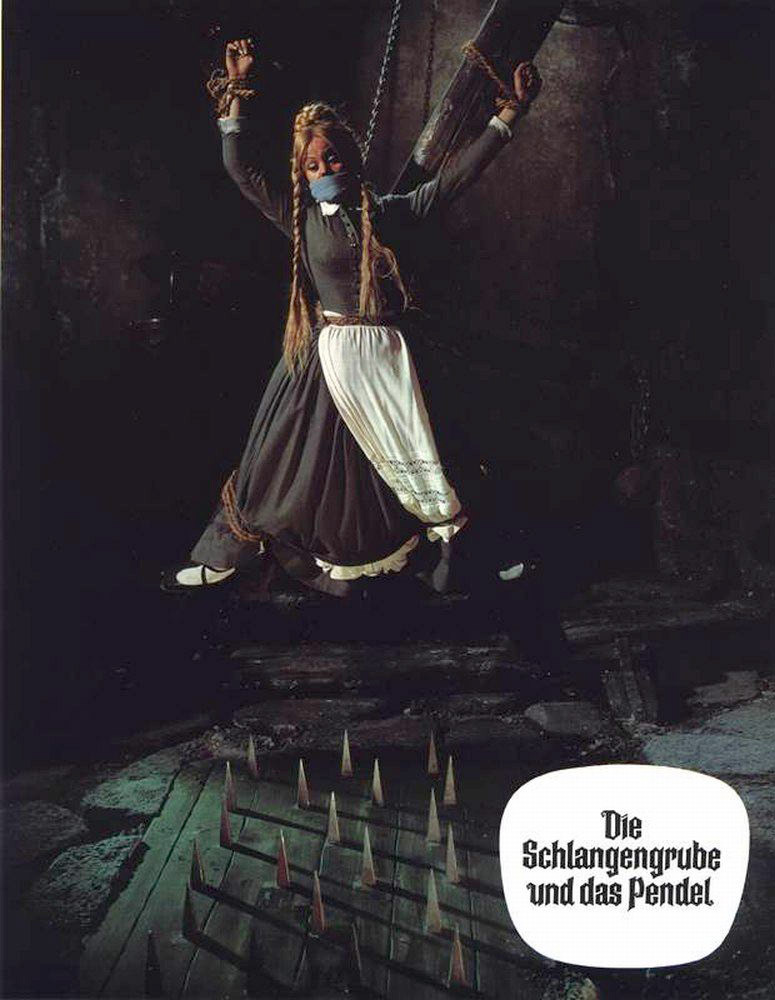

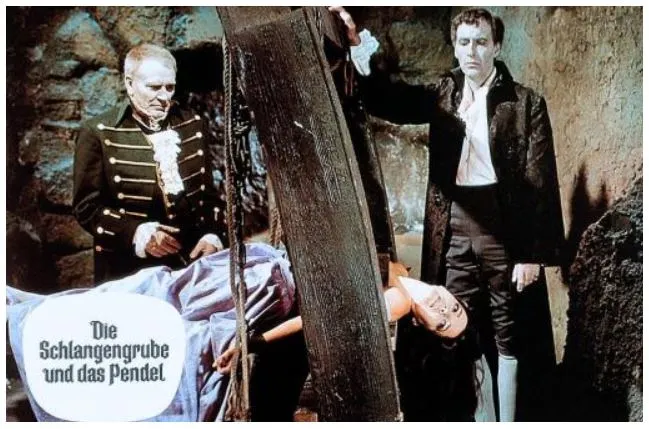

![[October 18, 1967] We Are The Martians: Quatermass and the Pit, Bonnie and Clyde, The Day the Fish Came Out and The Snake Pit and the Pendulum](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671018posters-672x372.jpg)

Likeable: Andrew Keir as Quatermass and Barbara Shelley as Miss Judd

Likeable: Andrew Keir as Quatermass and Barbara Shelley as Miss Judd Colonel Breen, representing humanity's negative side.

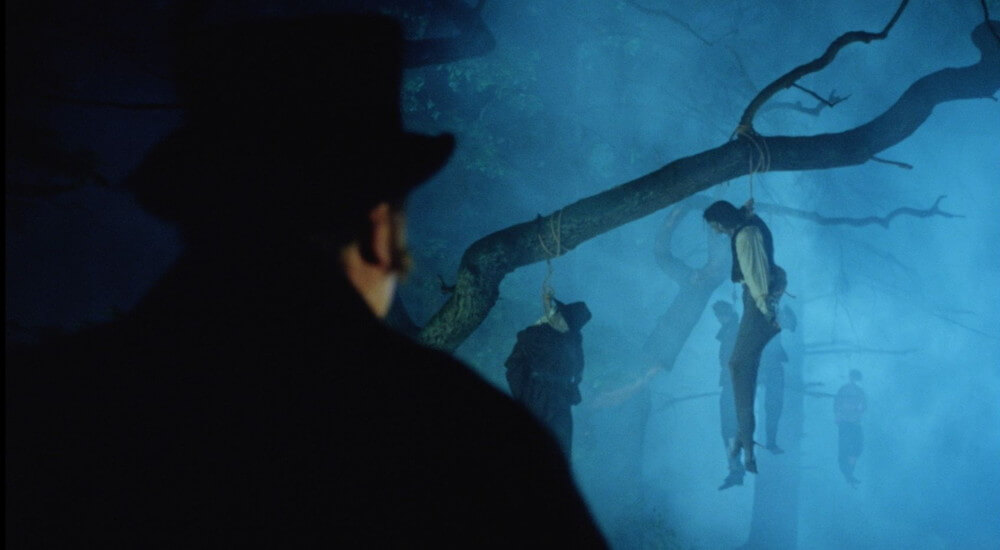

Colonel Breen, representing humanity's negative side. Hammer's take on the Martians.

Hammer's take on the Martians.

![[October 16, 1967] A Frosty Reception (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Abominable Snowmen)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671016moreyeti-672x372.jpg)

![[October 14, 1967] Threat level: High (October Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671014covers-672x372.jpg)