by Kaye Dee

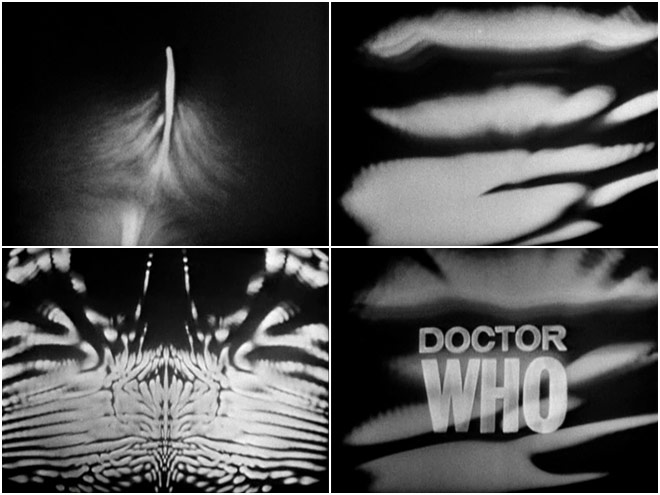

I’ve been reading Jessica Holmes’ insightful articles about the British science fiction television series Doctor Who since she first started commenting on this show (see December 1963 entry) and I’ve been looking forward for some time to actually seeing it air in Australia. At last my wish has been granted! The T.A.R.D.I.S. has finally landed here, with Doctor Who commencing on the Australian Broadcasting Commission (the ABC is the Australian equivalent of the BBC) just in the past week, mesmerising me with those incredible opening credits.

Doctor Who's ethereal and abstract opening credits perfectly suggest travelling along the corridors of time

Not Just Kid Stuff

I heard from a friend who works at the ABC that Australia has been one of the first countries to buy Doctor Who from the BBC. In fact, I was really excited when he told me in March last year that the ABC had purchased the show and intended to debut it last May, but then delays arose due to censorship issues. Yes, although Doctor Who is classed as a family show in Britain, the Australian censors (who view and classify every overseas television show that comes into the country) have deemed the first thirteen episodes to be not suitable for children and classified them as “Adult”! This means that the ABC must schedule these episodes for screening after 7pm and couldn’t show Doctor Who in the Sunday night 6.30pm timeslot it originally planned. But at last Doctor Who has found a home on Friday night at 7.30pm (at least in Sydney). I just hope the censors aren’t going to decide one day that some stories are too scary to be screened at all!

Doing the Rounds

A funny thing about the ABC is that sometimes when it buys a show from overseas it only purchases one film copy of each episode. This film reel then has to be sent around from state to state so that it can be screened by the ABC broadcaster in each capital city. So, the first Australian screening of Doctor Who was actually in Perth on Tuesday, 12 January. Sydney and Canberra (linked by cable) were next on 15 January. Brisbane will get to see Doctor Who next Friday 22 January, but Melbourne will have to wait until Saturday 20 February and Adelaide won’t see the first episode until Monday 15 March! I’m glad I live in Sydney now.

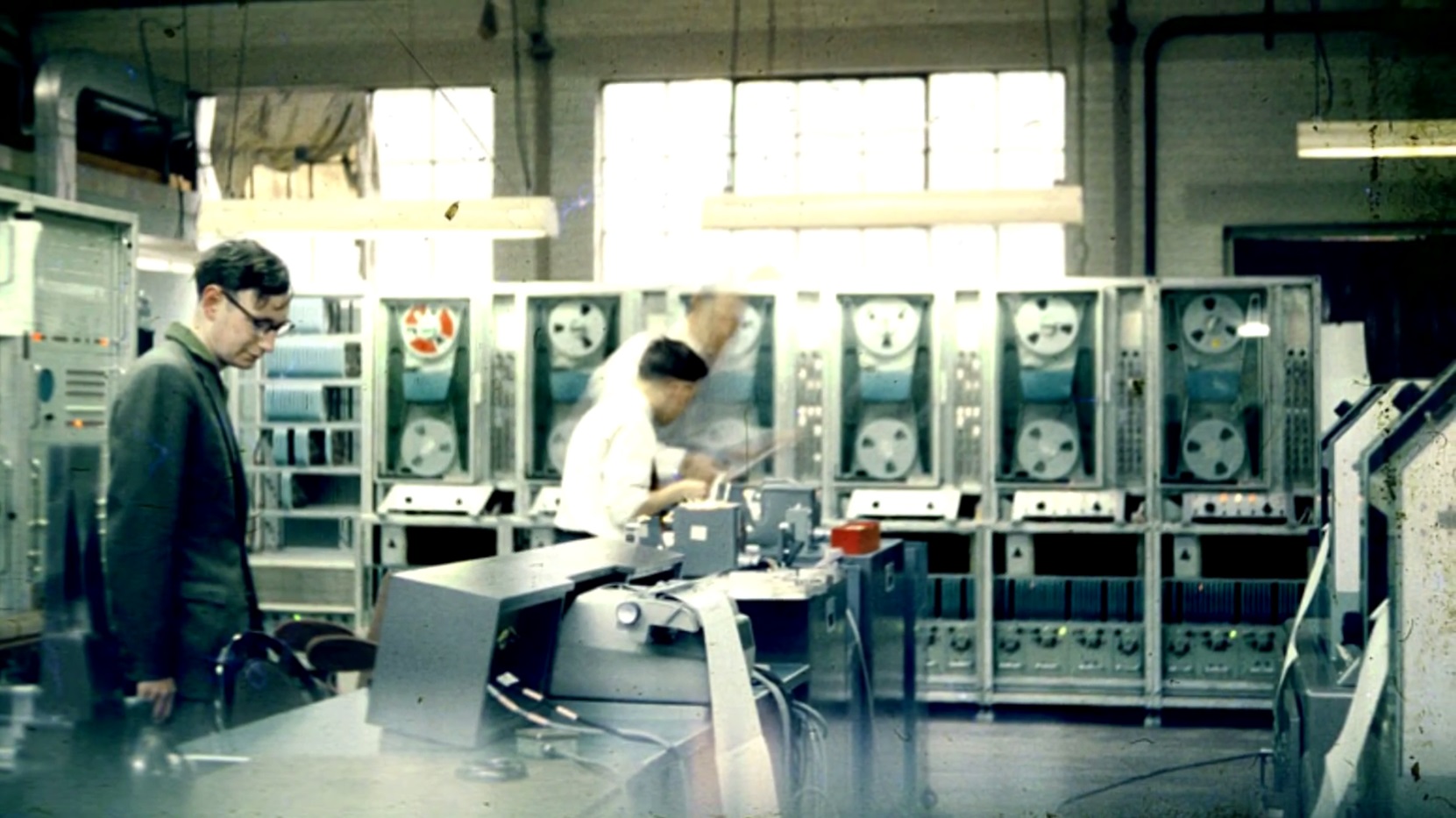

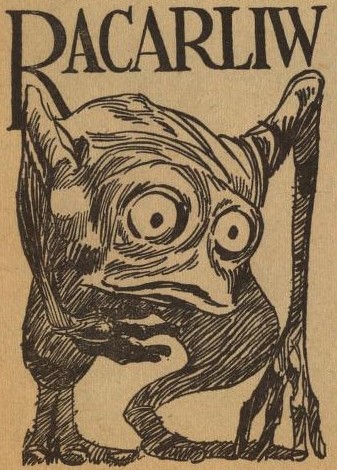

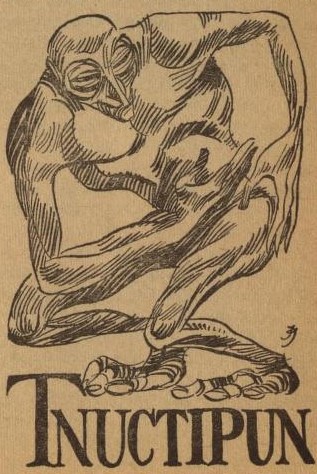

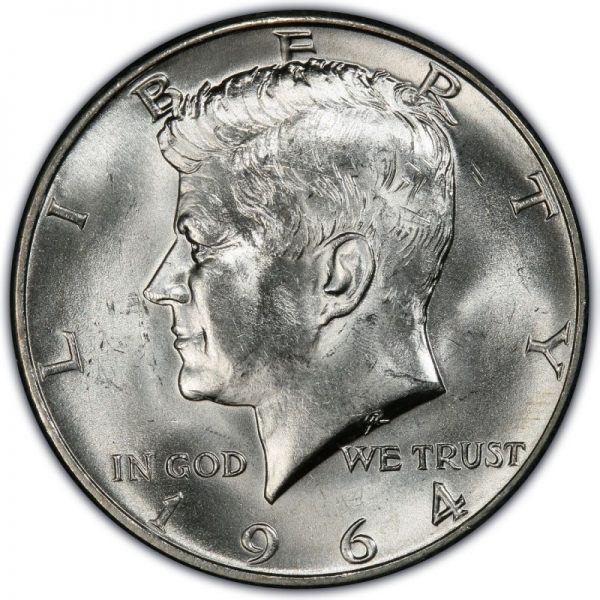

Anthony Coburn (left) and Ron Grainer (right) may be virtually unknown in Australia, but they've had successful careers in Britain and have made important contributions to the creation of Doctor Who

The Australian Connection

It’s great to see that some Australians are involved with the production of Doctor Who. The premiere story, “An Unearthly Child” has been written by Anthony Coburn. I’d never really heard of him before, but according to a few newspaper articles reviewing the first episode he was born in Melbourne and has been working in England for many years as a staff writer for the BBC. Ron Grainer, who composed the wonderfully eerie and evocative theme music, has also spent most of his professional career composing music in Britain, although he grew up in a small mining town in far north Queensland. Vicki Lucas’ fascinating article on the music of Doctor Who (see December 1963 entry) tells me that an obviously talented lady named Delia Derbyshire at the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop created the amazing sound of Grainer’s composition: all I can say is that I’m in awe of her skill at creating electronic music, now that I have actually heard the theme tune for myself.

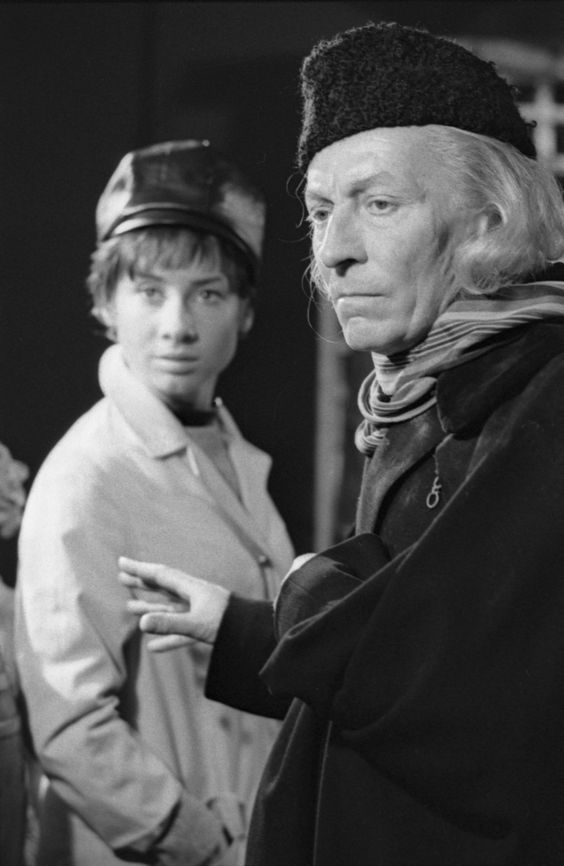

The mysterious Doctor Who and his granddaughter Susan. I wonder when we'll find out where they really come from and why they are exiles from their home world

A Family Viewing Experience

And that’s what I’ve discovered with the first episode of Doctor Who: it’s one thing to read about the show and look forward to seeing it, but it’s a whole new experience to actually watch it on television. My sister Faye and her kids watched “Unearthly Child” with me and we were all caught up in the mystery of Susan and her grandfather and what's going to happen to the two school teachers now that they've been whisked away somewhere in time and space in the Doctor’s T.A.R.D.I.S. Vickie and David certainly didn’t think that Doctor Who was just for adults, no matter what the censors said! We’re all looking forward to the next episode and enjoying the adventures that those of you in Britain have been watching for over a year.

Promotional image for The Samurai, showing Shintaro wielding a longsword that is the traditional weapon of a samurai warrior. The title character is played by actor Koichi Ose

Japanese Television Arrives in Australia

Doctor Who isn’t the only new television import to catch my attention lately. Despite the animosity that many Australians have felt towards Japan since the War, last year’s Tokyo Olympic Games, where our young swimmer Dawn Fraser did so well, sparked a lot of interest and curiosity about Japan and its culture. So much so, in fact, that TCN-9 in Sydney started showing the first ever Japanese television series on Australian screens at the end of December. It’s an action adventure series called The Samurai, set in feudal Japan three centuries ago. Channel 9 is taking a gamble with this show, which I guess is why they’ve put it on in the doldrums period of the Summer holidays.

Shintaro narrowly avoids a brace of 'star knives' (a weapon used by the ninjas). I've heard that Dads are now making home-made ones for their kids, snipped from used tin lids. It'll be fun to play samurai and ninjas until someone gets hurt with one of these!

A "Western", Japanese Style

The Samurai tells the story of a master swordsman named Shintaro (the “samurai” of the title), a half-brother of Japan’s young ruler, the Shogun, who travels around Japan putting down plots against his brother’s government, usually by the villainous gangs of a semi-magical secret society known as ninjas: you could say that Shintaro is a medieval Japanese cross between James Bond, a Western gunslinger and Robin Hood! Channel 9 has been showing The Samurai five days a week at 3.30pm and with its exotic setting, supernatural action and endearingly bad dubbing with broad American accents, it’s fast becoming very popular – and not just with the kids. Faye’s husband, Bruce, has been absorbed in the show while he’s on holidays and I’ve taken to this fascinating curiosity of a show as well. Mind you, so many ninjas get killed in each episode, I’m surprised the censors haven’t labelled The Samurai as “Adult”, alongside Doctor Who!

Japan Invades the Top 40, Too

Another bit of Japanese culture has also been making its presence felt in the Top 40 charts. In August last year, the lovely Noeleen Batley, Australia’s first female pop singer to have a national hit song, released an English version of a song that was a huge hit in Japan in 1963. “Little Treasure from Japan” charted in Sydney and Brisbane and even made it all the way to #16 in Melbourne last October. It really is a sweet little song, with one of those tunes you can’t get out of your head. My niece Vickie’s dance teacher is already creating a dance routine for her class to perform to the song for their mid-year concert. Now we just have to figure out where we can find a kimono for her costume.

Australia's "Little Miss Sweetheart" Noeleen Batley has had a hit with "Little Treasure from Japan". You can see by the wear on the cover that Faye's copy of the record has already been played quite a bit

Australia International

The fact that Channel 9 took a risk on screening The Samurai is an indication of how much Australians have broadened their worldview since the end of the War. The large influx of European migrants has introduced us to delicious new foods, good coffee (thank you!) and a more cosmopolitan outlook. Our TV might be dominated by British, American and (a long way third) Australian shows now, but hopefully we'll soon see more international programmes. Perhaps someday we'll even see a television channel offering programmes from around the world: I can't wait to see what fun and entertainment we've been missing out on!

[If you have a membership to this year's Worldcon (in New Zealand) or did last year (Dublin), we would very much appreciate your nomination for Best Fanzine! We work for egoboo…]

![[January 20, 1965] The T.A.R.D.I.S. Lands Down Under and Japan Invades Australia (<i>Doctor Who</i> and <i>The Samurai</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/DW-and-Susan-564x372.jpg)

![[January 18, 1965] Doors also open (February 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650118cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 16, 1965] What a Difference a Year Makes (<i>The Outer Limits</i>, Season 2, Episodes 13-17)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650116end-672x372.jpg)

![[January 14, 1965] The Big Picture (March 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v02n06_1965-03_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[January 12, 1965] Last Minute Reprieve (the February 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/amz-0265-cover-1-521x372.png)

![[January 10, 1965] A Little Breather (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Rescue)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650110koquillion-672x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1965] The Skylark of Space (Britain's Skylark Sounding Rocket)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Skylark-with-Cuckoo-672x372.jpg)

![[January 6, 1965] Plus C'est La Même Chose (February 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650106cover-518x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1965] Madness: 2, Sanity: 1 (January Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650104covers-672x372.jpg)

![[January 2, 1965] Say that again in English? (Talking to a Machine, Part Two)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/650102comp-672x372.jpg)