by Gideon Marcus

Up in the Sky

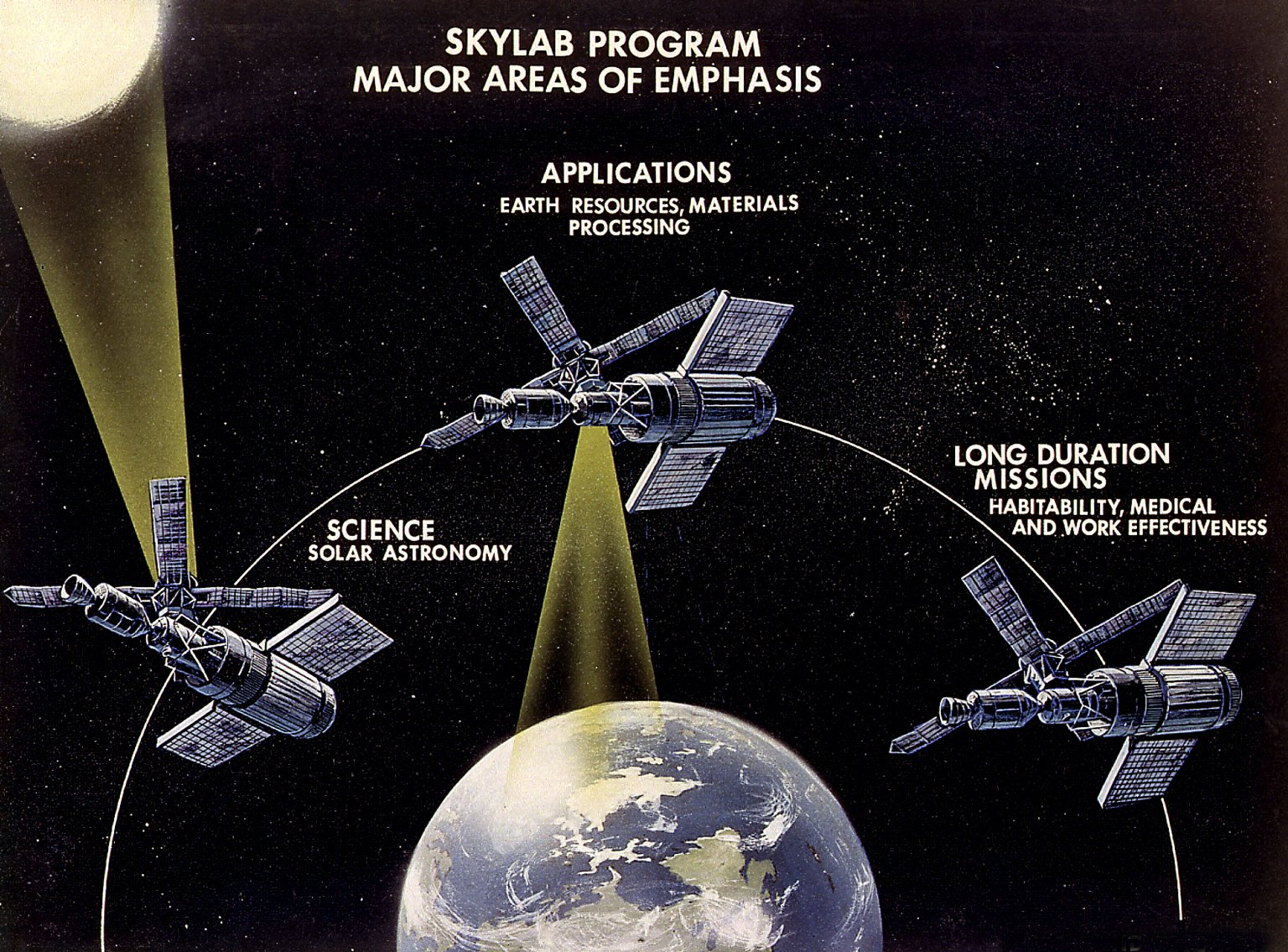

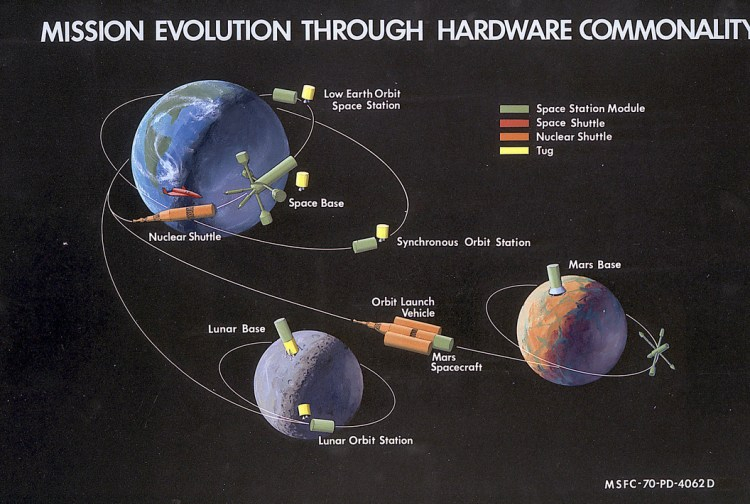

Apollo 13 may have made for great TV, but it's been terrible for NASA. This morning, in testimony before Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, NASA Administrator Dr. Thomas O. Paine reviewed the results of the Apollo 13 accident investigations and announced that the next (Apollo 14) mission had been postponed to Jan. 31, 1971–a three month delay. I imagine this is going to snarl up the meticulously planned schedule of Apollos 15-19, especially since Skylab is supposed to go up somewhere in that time frame.

…If any of these missions happen. In a recent poll of 1520 Americans, 55% said they were very worried about fate of Apollo 13 astronauts following mission abort, 24% were somewhat worried, 20% were not very worried, and 1% were not sure. More significantly, a total of 71% expected fatal accident would occur on a future mission. Perhaps its no surprise that the American public is opposed by 64% to 30% to major space funding over the next decade.

The scissor-wielders on Capitol Hill are heeding the call. Yesterday, Sen. Walter F. Mondale (D-Minn.), for himself, Sen. Clifford P. Case (R-N.J.), Sen. William Proxmire (D-Wis.), and Sen. Jacob

K. Javits (R-N.Y.), submitted an amendment to H.R. 17548 (the Fiscal Year 1971 Independent Offices and HUD appropriations bill. Not a happy one.

It would reduce NASA's R&D appropriation by $110 million–which just happens to be the amount requested by NASA for design and definition of space shuttle and station.

Mondale excoriated the proposal: "This project represents NASA’S next major effort in manned space flight. The $110 million. . .is only the beginning of the story. NASA’s preliminary cost estimates for development of the space shuttle/station total almost $14 billion, and the ultimate cost may run much higher. Furthermore, the shuttle and station are the first essential steps toward a manned Mars landing. . .which could cost anywhere between $50 to $100 billion. I have seen no persuasive justification for embarking upon a project of such staggering costs at a time when many of our citizens are malnourished, when our rivers and lakes are polluted, and when our cities and rural areas are decaying."

This seems a false choice to me. Surely there is such wealth in this country that we can continue the Great Society and the exploration of space, especially if we gave up fripperies like, oh I don't know, the war in Cambodia. To be fair, I know Fritz Mondale opposes the war, too, but we're talking a matter of scale here–the shuttle and station are going to cost peanuts compared to the outlay for the military-industrial complex.

That said, maybe Van Allen is right, and we shouldn't be wasting money on manned boondoggles, instead focusing on robotic science in space. On the third hand… "No Buck Rogers, no Bucks."

What do you think?

Down on the Ground

Illustration by Leo Summers

Well, if we lose our ticket to space in the 1970s, at least we'll have our dreams. Thank goodness for science fiction, and even for the July 1970 issue of Analog. Dreary as this month's mag is, it's got enough in it to keep it from being unworthy.

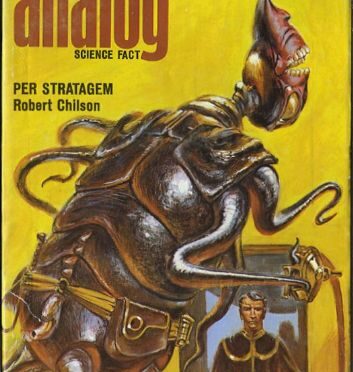

Per Stratagem, by Robert Chilson

Illustration by Leo Summers

Hal Clement has made a living translating scientific concepts into hard (very hard) science fiction tales. Such stories tend to be light on characterization and heavy on technical details, but usually fascinating nonetheless. Robert Chilson offers up Per Stratagem, a very Clementian tale, with some Campbellian embellishments.

Rahjikah is a faction leader of an an extremely alien race. His people evolved and are adapted to the weightless expanse of space, able to maneuver at high acceleration using internal gas jets. The factions of his race are locked in a vicious struggle for control of their solar system, the two light-year expanse that makes up the "Outer Sphere." Think 17th Century pirates, only on the High Vacuum, using organic ships and Newtonian trajectories.

Enter human interference. The "Outsiders" came upon the alien system as a fleet of small commercial explorer ships. Quickly overcome by the extraterrestrials, their ships have been commandeered to be invincible raiders. Now, the Bowling Over has arrived, bigger than all the prior vessels, and Rahjikah is determined to take it over all by his lonesome, to make him the most powerful being in the Sphere.

But as resourceful as the alien pirate is, you know he will ultimately be no match for Bowling's captain, Marshall Irons…

The long, technical descriptions will sometimes make your eyes cross, but it is fun seeing humans from a truly alien viewpoint. Of course, Rahjikah isn't really alien, despite his make-up–like any Clementian being, no matter how oddly shaped, his motivations are thoroughly relatable to the human reader.

In the end, Per Stratagem is fun and creative, and the physical aspects of Rahjikah's race are interesting, but the story is a pat and forgettable one.

Three stars.

Beau Farcson Regrets, by Jack Wodhams

Illustration by Kelly Freas

A time traveler from some time in our near future takes a jaunt to 18th Century England. Sadly, he materializes 20 feet above the ground and suffers a broken leg upon landing. Thus begins a many week-long nightmare that dispells any romantic notions a modern person might have about living in the past.

This is a delightful, if inconsequential, tale. Thank God for Progress…and Ignatz Semmelweiss!

Four stars.

Rare Events, by D. A. L. Hughes

Illustration by Leo Summers (say, is the little guy Harlan Ellison?)

Smithson, a philosopher of science, finds himself acquainted with six scientists with disparate, exotic fields of study. One is hunting magnetic monopoles, another for tachyons, a third for quarks, a fourth for evidence of gravitational waves. Two more, mixed in without bias, are interested in telepathy and dowsing, respectively. All know that the odds of detecting telltales of these far out processes is low, but each is convinced of the worthiness of his endeavors.

The subtext of this talky, plotless piece, of course, is that pseudoscience is in the same category as advanced theoretial physics. This is a story made to tickle Campbell's heart.

Two stars.

Ark IV, by Jackson Burrows

Illustration by Leo Summers

This piece started intriguingly enough, with a Taal, High Priestess of Systems, communing with her blinkety light panel, as she does every year that she is awakened from suspended animation to talk to the God-computer. A generation ship story, right?

Well…

Turns out that Taal's "ship" is a whole planet, and there are hundreds of these things, called Wanderers–artifacts of a prior time and another (completely human for some reason) race. It's up to the doughty members of the (human) Ark corps to stop Taal's Wanderer before it makes a close brush with the colony world, New New Rochelle.

For some reason, Taal comports herself like a Bronze Age holy woman, but the Ark corps folk, despite residing centuries in our future, talk and act just 20th Century men…up to and including taking a moment to luridly admire the gams on the priestess.

And all of it is just a setup for the revelation of what "Ark" really means in the context of the story. (Note: it does not refer to Taal's planet being a "space ark"). I don't have much use for punchline tales, especially a retread of a Star Trek episode.

Two stars.

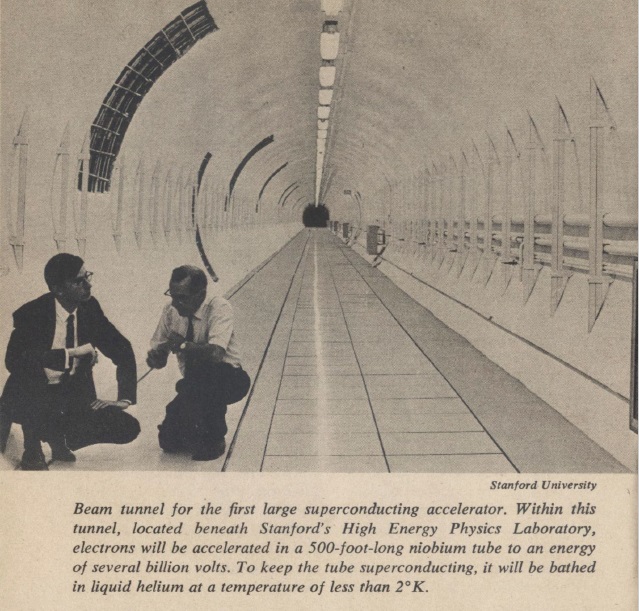

Zero Resistance, by Walter C. Walterscheid

I have a suspicion this article is actually by Edward C. Walterscheid, who has contributed a number of technical pieces to Analog over the decade. He's one of the better science contributors Campbell has, and this article is one of the better science pieces.

It's all about the new science of superconductors—at low temperatures, certain substances lose all electrical resistance whatsoever, and this allows them to hold permanent magnetic fields, conduct power without waste heat, and more. Apparently, all the really exciting developments have happened in just the last decade.

The topic is fascinating. As for the reading, the first half and the last sixth, covering history and some applications, are terrific. The remaining third is technical enough to cross your eyes. I'd love to see more on what you can do with superconductors; for instance, how they are used in the search for subatomic particles.

Three stars.

"Some Like It Hot, Some Like It Cold …", by John W. Campbell, Jr.

A nice two-pager about some Earthbound creatures with tolerance to extreme heat and cold. Campbell extrapolates that, if they can withstand Earth's extremes, they can deal with Mars'. Of couse, he neglects to note that while there are bacteria that can handle near-boiling temperatures, and bugs that can handle sub-Arctic cold, we haven't found a creature that can do both. Mars' temperature extremes are wider than Earth's, and that's before we talk about the lack of air and other inhabitability issues on the Red Planet.

Still, three stars.

Star Light (Part 2 of 4) , by Hal Clement

Illustration by Kelly Freas

The adventures of the Kwembly, a Mesklin-ite crewed land cruiser exploring the super-planet Dhrawn, continue. Last installment, we learned that though the high-gee stars of Clement's Mission of Gravity were ostensibly working for the humans in their survey of Dhrawn, it turns out the Mesklinites have secret plans of their own: they are establishing a secret base for their own purposes.

This installment begins with the Kwembly frozen in a patch of ammonia/water ice. It's really a triptych, each section containing a lot of discussion of a particular problem to be solved. For the first, it's humans discussing why the Mesklinites have been so cagey about their intentions and their reluctance to use too many human technological conveniences. The second involves two helmsmen trapped under the ammonia-water ice trying to work their way out before they freeze. The last has young Benj (a human) working remotely with Dondragmer (the Kwembly's captain) to find a way to use the ship's power to melt the ice.

It all reads like illustrative passages from a textbook. Mildly interesting, but perhaps weighted a bit too heavily on science and insufficiently on fiction.

A low three stars.

The Reference Library: Two by Boyd (Analog, July 1970), by P. Schuyler Miller

Schuy offers up some effusive praise for the new SF author John Boyd, particularly Sex and the High Command (which left George cold when he reviewed it). He also likes I Sing the Body Electric, which he calls Bradbury's "best collection in a long time." George, again, was more reserved.

Analog's reviewer goes on to nod approvingly at this year's Nebula Awardees, but he is less effusive about The Eleventh Galaxy Reader. I still fondly remember the second such volume Galaxy put out, and I have to agree with Schuy's sentiment when he says, "Galaxy has been made its publisher's second-string magazine. I can't imagine why."

Finally, Miller reviews Ian Wallace's Dr. Orpheus, a sequel to Croyd, neither of which I've read, but which the reviewer quite enjoyed. At one point, though, he seems to confuse Wallace for Edmond Hamilton. A pseudonym? Freudian slip?

Summing Up

That's that! 2.9 stars for this middle-of-the-road summer issue. It scores beneath IF (3.3), Fantasy and Science Fiction (3.2), and Vision of Tomorrow (3.2), ties with an improving Amazing (2.9), and only really savages the peculiarly substandard Galaxy (2).

Women wrote just 7.5% of what was newly printed this month, and you could fit all the four and five star pieces in two regular magazines.

And so, science fiction limps along like NASA's space program—underdeveloped, somewhat aimless, but not without moments of triumph and drama. Let's hope fact or fiction soon break out of the doldrums to inspire the other onward!

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

Of course we can pursue the Great Society and keep the space program fully funded. It's not a lack of money that's keeping the government from making sure that people have enough to eat, that our air and water are clean, or any of the other things Senator Mondale mentions; it's a lack of political will. A couple of years ago, LBJ asked congress for a fairly small amount of money to combat rats and other pests in cities. It got shot down so hard, not even all of LBJ's skill and knowledge of where the bodies are buried could revive it. The government could be running a surplus and you still wouldn't be able to get any of the senator's priorities through congress.

"Per Stratagem" was pretty good. At least until the story got to the human motivations. I'm sure Campbell's thrilled with the colonialism of the resolution, but a few decades down the road this sector of space is going to be a mess. The alien stuff is good, though.

"Beau Farcson" is the first story by Wodhams I've come close to liking. I can't get all the way to four stars, though. If nothing else, the protagonist seems woefully unprepared for his journey.

"Rare Events" is clearly written to sell to Campbell, which doesn't necessarily mean it's going to be bad, but sure handicaps it. A more talented author might have been able to scrape a decent story out of the premise, but Hughes is not that author.

"Ark" was tedious and also clearly designed to check off some of Campbell's boxes. It felt like it could have been written 20 years ago.

The science article wasn't bad, but it wasn't that great either. It's about what you can expect for a high-end Analog article. Campbell just can't seem to grasp that a popular science article shouldn't read like something from a technical journal.

I continue to like "Star Light" more than you do. Probably because I just like Clement in general more than you. Sometimes I wonder what he's like as a teacher (he teaches science at a fancy high school back East somewhere) and if his students know Mr. Stubbs is famous within certain circles.

I'm sure the kids know Stubbs is famous by now! Thank you, also, for your comments on the lead. I feel like most people skip the news to go straight to the stories.

I also feel like you have momentum against/for certain authors. Kris was shocked I liked a Wodhams story, but I take everything fresh, even from known stinkers.

Thanks for the kind thoughts on "Per Stratagem" … very kind, as you rate it higher than I do. I would probably like my original version better, I had the alien protagonist killed off at the end by an ingenious he said modestly method. John Campbell suggested strongly that the aliens would make great allies and that the hero should befriend them. He was setting me up for a sequel if not a series, and I started one, but found that I'd said all I had to say on the topic. I remember that I enjoyed working up the alien race (they talk in Morse code, I remember, and use binary digits), and I liked making the viewpoint character the villain. —This inability to do sequels has hampered my so-called career, but at least none of my stories has a knock-kneed follower shambling along behind….