This month saw such a bumper crop of books (and a bumper crop of Journey reviewers!) that we've split it in two. This first one covers two of the more exciting books to come out in some time, as well as the usual acceptables and mediocrities. As Ted Sturgeon says: 90% of everything is crap. But even if the books aren't all worth your time, the reviews always are! Dive in, dear readers…

by Victoria Silverwolf

Three quarters will buy you a copy of the latest Ace Double. You might want to use one of those quarters before you purchase it to decide which of its two sides to look at first. Heads Bulmer, tails Sutton.

Or you could do what I usually do and start with the shorter one. In this case, Bulmer's yarn is about fifty pages shorter than Sutton's. That makes it a novella in my book (pun intended) rather than the Complete Novel the publisher claims that it is. Oh, well, that's the publishing business for you. Let's dive in anyway.

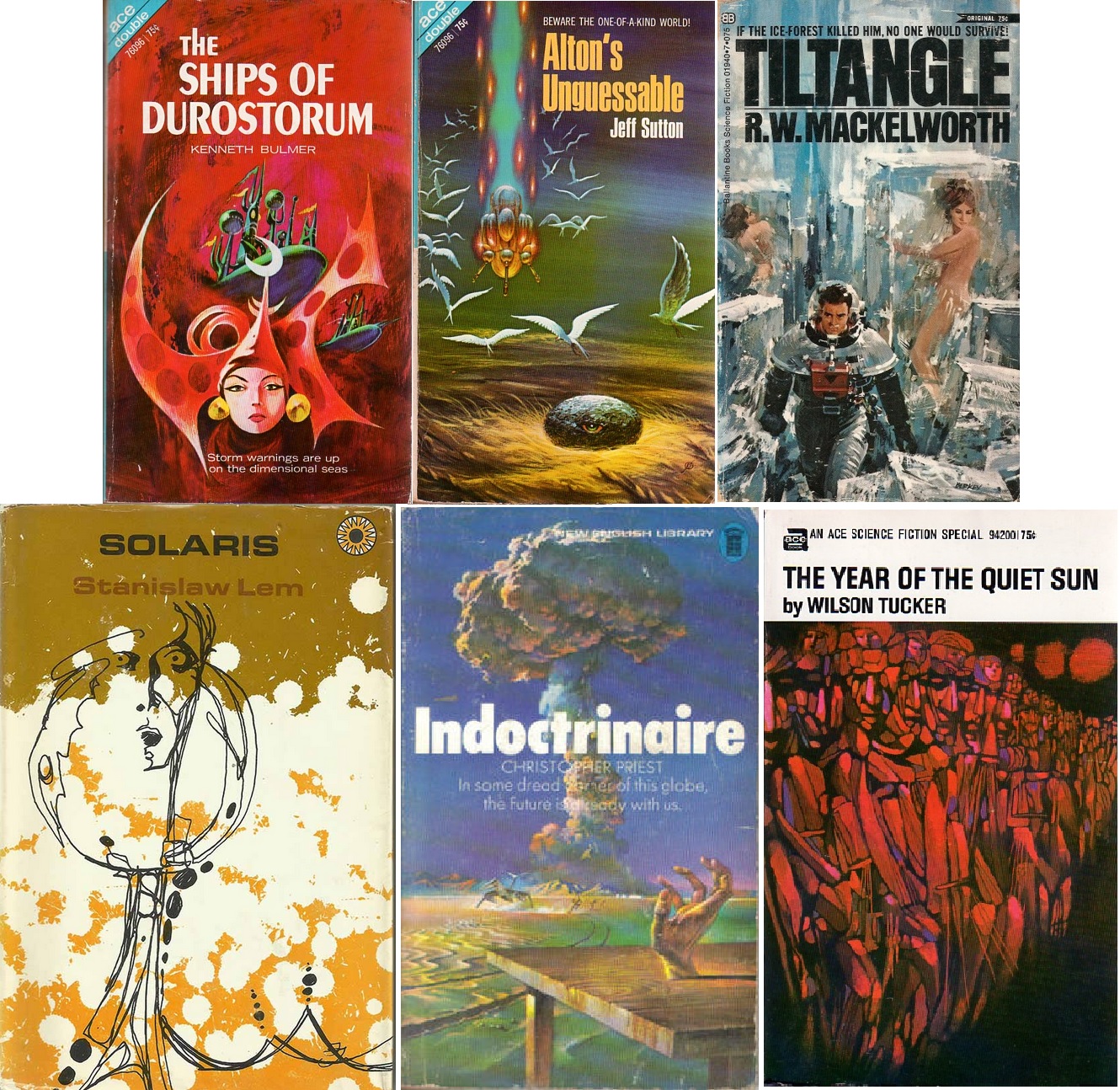

The Ships of Durostorum, by Kenneth Bulmer

Cover art by Jack Gaughan.

The first thing to note is that there are other works by Bulmer that are part of the same series.

Helpful information from the publisher.

I haven't read any of the starred novels (novellas?) and it seems like only The Wizards of Senchuria has caught the eye of a Galactic Journeyer. My esteemed colleague Jason Sacks gave it four stars, which is promising.

Our hero is J. T. Wilkie, a mining engineer. He and his buddy are trapped in a coal mine explosion. Fortunately, they're saved when a woman from another dimension transports them into yet another dimension.

Let me back up, because we don't meet Wilkie until Chapter Two. In Chapter One we meet the woman, who has the impressive name of Contessa Perdita Francesca Cammachia di Montevarchi. As is mandatory for a villainess in this kind of action-packed tale, she's stunningly beautiful and pure evil.

Wilkie doesn't realize that the Contessa is the antagonist of the story. After some random adventures in different dimensions, he and his pal reach her homeland. She wants him to be her mining engineer for her gigantic diamond mine. The reader is aware that this operates on slave labor, but Wilkie doesn't catch on. In fact, it seems like a pretty good deal, especially compared to dying in a coal mine.

When something bad happens during a failed attempt at rebellion by the workers, Wilkie becomes even more convinced that the Contessa is on the side of the angels. After he modernizes her mining operation, she sends him on a quest to obtain a gizmo that will make traveling between dimensions easier.

Let me explain. It seems that there are portals between dimensions, but only a small number of people have the ability to detect them and use them to send other folks through them. The Contessa has one such gifted person kept chained to her left wrist, which should have given Wilkes a clue that she's not a nice lady.

A device from another dimension (I'm losing track of them by this point) would allow the Contessa to use the portals without relying on these gifted people. Grabbing it requires an assault on a stronghold.

Suffice to say that a big battle follows in a dimension where the title ships fly through the air. It's kind of like a pirate movie if you lifted the ships out of the water. Along the way we get our mandatory love interest, a woman from (you guessed it) another dimension.

A lot goes on! I can't accuse the author of padding the novella with extraneous material. It might help to be familiar with other works in the series, I suppose. There are references to enemies of the Contessa and to the Wizards of Senchuria, but they don't play a role in the plot. The ending is inconclusive, so I expect sequels to follow. It's not boring, but it seems like a lot of sound and fury signifying not much.

Two and one-half stars.

Let's flip the book over and move on.

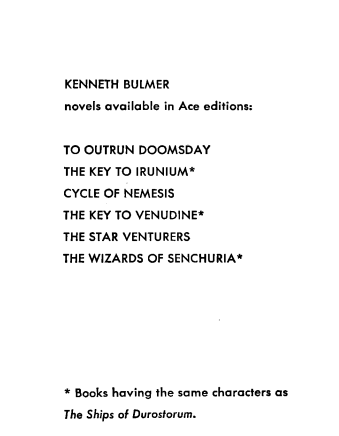

Alton's Unguessable, by Jeff Sutton

Cover art by Kelly Freas.

Thousand of years in the future, a starship carrying scientists, officers, and other crew members arrives at a planet in a remote part of the galaxy. It seems to be one of the few planets that would be perfect for human colonists. The environment is pleasant, but the weird thing is that the only forms of animal life are gull-like birds and rat-like rodents.

(Forget the rodents. They play no part in the plot, as far as I can tell.)

This is certainly bizarre enough. Further complicating matters is the fact that our protagonist, Roger Keim, is the ship's telepath, and he's getting weird, vague sensations that there's danger around. A scientist named Alton suggests that something unguessable is going on, hence the title.

Because the author is going for suspense rather than mystery, we know that the planet is inhabited by an unimaginably ancient organism that arrived there after leaving the edge of the universe. It's the last of its kind. I might as well mention the fact that its name is Uli and it's a member of the Qua species.

The Qua had tiny bodies — pretty much a lump of tissue with a single eye — but enormous mental powers. When they began dying out billions of years ago, they sent Uli and a few others out into space. The others all died along the way in various manners.

The planet used to be inhabited by bipeds who came to worship Uli. It completely wiped them out, destroying almost every trace of their civilization. It also got rid of all animals except the pseudo-gulls and the pseduo-rats.

Uli has his mind inhabiting the birds. It's been waiting an incredibly long time for a species that can travel through space to arrive. (The native bipeds weren't technological enough, it seems.)

The cautious folks from the starship investigate the place, placing a force field around their vessel. Things start to get weird when they notice that the birds avoid the force field, as if they can sense it in some manner. Then a member of the crew dies in a gruesome way when one of the birds looks in his eyes.

You see, Uli wants to transfer its mind into important people on the starship so it can use the ship to find a planet where it can dominate the local species. Then it plans to reproduce (via fission) and go on to conquer the galaxy. Its first attempt didn't quite work out, hence the death of the crew member.

What follows is a science fiction horror story of possession and bloodshed. How do you fight an enemy that can take over your body and who can destroy an entire landscape with its mind?

Roger gets some help from another member of the crew who is secretly a telepath like him, even hiding it from herself. If you think she's also the novel's love interest, go to the head of the stereotypical pulp fiction writing class.

The author creates a great deal of tension, and it's not obvious that the good guys are going to win. The whole thing is kind of like the grimmest episode of Star Trek imaginable.

Three and one-half stars.

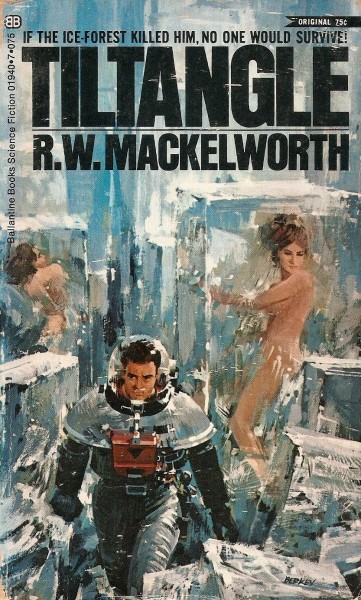

Tiltangle by R.W. Mackelworth

by George Pritchard

The early version of Tiltangle, in short story form, was previously covered by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall last year. As mentioned in the original article, the Frozen World setting is currently popular amongst UK authors, and while I find the setting interesting, Tiltangle does frustratingly little with the concept.

Several generations ago (”never mind how long precisely”), a group of refugee humans fled in massive boats to White Mountain, an immense complex where they believe they hold onto the one remaining population of humans. However, supplies are running short, and it is believed that more may lie elsewhere, possibly with the mysterious raiders that survive in the icy wastes. But there are rumors of something even more astounding — “the warm”, the world of warmth and life that their ancestors left behind. The story follows four characters — Tomas, Donna, Joth, and Amaro. Tomas is the strong yet distant young man, Joth is the older rule-follower, Amaro is smart (and Black!) and Donna is female.

Cover art by John Berkey.

As they traverse this great icy waste in search of “the warm”, it steadily becomes clear that all is not as it seems, with White Mountain and its attached Base One, and the old man who has led them for so long. In fact, it seems that there are endless amounts of “supplies”, including food (presumably canned) that can last the people of White Mountain for centuries, but they have been kept hidden. There is an offscreen rebellion, and then all of the supplies and people are moved through a secret tunnel to get away from Base One before the old man blows it up. I might have been easier on this book if this wasn't nearly identical to the ending of

This was a difficult story to review. As I read it, I could not remember what had just happened, where the characters were, what they were doing, and the general timeline of events that had led the characters to their present situation. Rereading would be possible, and yet I was loath to do so for this specific book. It is not because the book is vile—more like the act of reading it feels like staggering through one of the whiteout storms of a frozen world. We are occasionally told things that have happened — usually supplying why something must happen, or why the characters are aware of something they should not be in a frozen waste. Incidentally, we never find out what the title is referring to, whether it is symbolic, or literal — has the world's axis shifted, leading to the frozen world? Is this about how different the landscape is from the present? Maybe it refers to the rockets that show up? I don't know, and I don't know if Mackelworth does, either.

There are some particularly British turns of phrase, such as a reference to a character being like "a rabbit hypnotized by a stoat", and there are some moments that suggest a vague gesturing towards commentary. Amaro doesn't trust cozying up to technological superiority because "his people had been tricked before". At the end, Donna reflects on how she has led people from White Mountain to the warm, and how that is a kind of destruction. The temptress speaks! The people of White Mountain are referred to as being weak, and it might be meant to be some kind of commentary about modern life, but this is thrown in for flavor more than anything, to make Tomas' manly blandness stand out all the more.

I’ve heard a great deal about this “New Wave” of science fiction, with a tendency towards psychedelic, surreal, drug-infused or internally focused stories. Some of my fellow authors have tired of them, and understandably so. However, I look forward to reading those in the future, rather than this warmed-over tale.

Two Stars.

by Gideon Marcus

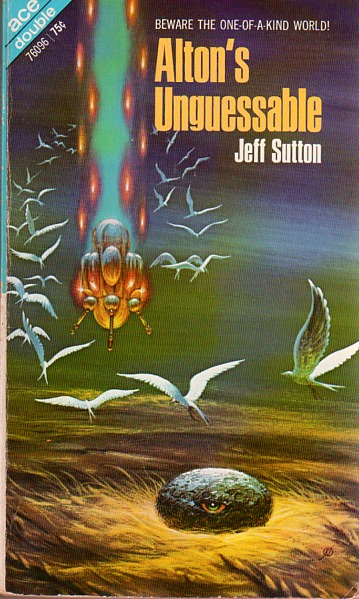

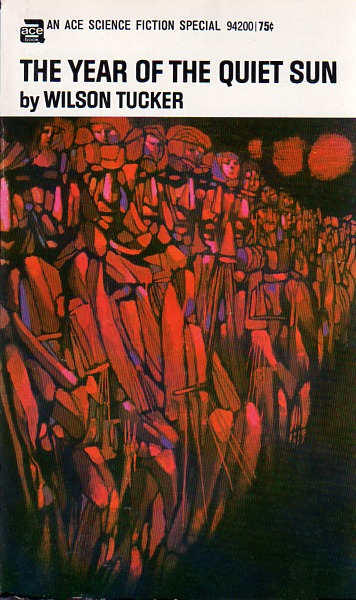

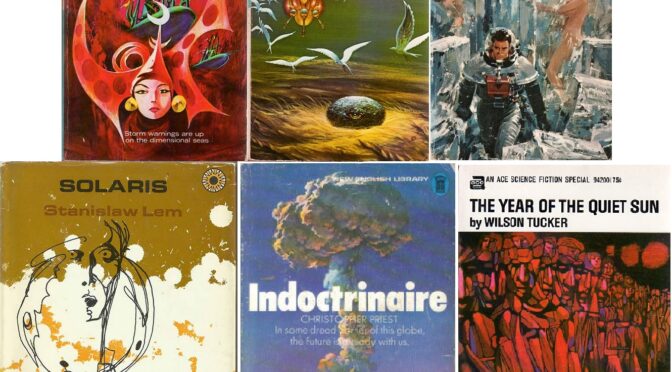

Year of the Quiet Sun, by Wilson Tucker

by Leo and Diane Dillon

The year is 1978. Brian Chaney is a man with a passion for history in both directions. An archaeologist/linguist who produced a controversial translation of Revelations, he is also a futurist for the Indiana Corporation: a think tank that produces statistical predictions for decades to come.

While resting on a beach in Florida, he is approached by Kathryn van Hise, of the Bureau of Standards. Her pitch is simple: join the Seabrooke project, and Chaney will have the opportunity to travel in time for real. Of course, he bites, not just for the chance at riding a bonafide time machine, but because he is quickly smitten with the lovely young agent.

Chaney's two fellow chrono-nauts are the straight-arrow Air Force Major William Theodore Moresby, obsessed with horoscopes and other divinations, and Navy Lieutenant Commander Arthur Saltus, a jocular young man with a perpetual sea-glare squint. The trio are trained for an important mission: to survey the near future to determine the resolution of a number pressing issues. Will civil unrest grow completely out of control? Whither the Asian war, now involving two million American troops and expanded to include China? How loose will clothing morals slip?

Once again, we have a fan-turned-filthy-pro Wilson Tucker offering a view of a bleak future for the United States. Unlike the weirdly made-over The Long, Loud Silence, which betrayed its early '50s origin despite the haphazard recent edits, and which had a plausible but utterly unsympathetic antihero, Quiet Sun is incredibly current, its protagonist thoroughly compelling. I should say protagonists, as Kathryn, Saltus, and Moresby are all well developed as well, and they all get their limelight moments.

Tucker is excellent at his craft, as usual. Even though the time travel jaunts don't even start until near the halfway mark, the training scenes and interactions between the characters keep the pages turning. Perhaps things are occasionally a touch repetitive and padded, but not uncomfortably so. And when the action really gets going, you'll tear through the rest in a sitting, for certain.

The most brilliant part of the book is the subtle revelation we get about Brian's background on page 128. It makes you rethink the entire context of the story, and it becomes more and more relevant as the book goes on.

Some science fiction stories are cautionary. Some are aspirational. This one is a bit of both, if perhaps leaning toward the former. Either way, it's definitely going to be one of my choices for this year's Galactic Star.

4.5 stars.

by Fiona Moore

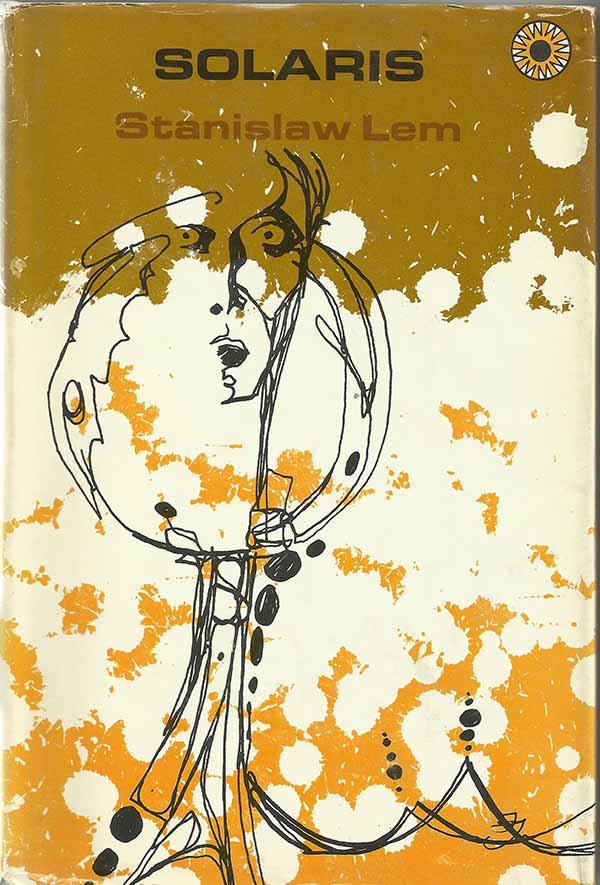

Solaris, by Stanislaw Lem (Translated from the French by Joanna Kilmartin and Steve Cox)

by Jack Gaughan

I was quite excited when I heard Solaris was coming out in an English translation this year. On my visit to Warsaw a couple of years back (hooray for détentes and East-West academic cultural exchanges), many of my colleagues were singing the praises of Stanislaw Lem as a genuinely original voice in Polish science fiction, but sadly I don’t read Polish, so was unable to discover him for myself.

Unfortunately, the translation we have isn’t directly from the Polish, but is a translation of a French translation from the Polish. Which left me feeling more than a little uncertain how to review certain aspects of the book. The prose has a stark, minimalist quality which I tend to associate with French literature— but is it also a feature of Polish literature, or an artefact of the translation process? What is Snow’s name in the original, and why has his name been translated when Gibarian and Sartorius’ names have not been? While I’m certain the plot and characters remain intact, I’m a little suspicious of how well the translation reflects the original.

The book is set on a research station orbiting the titular exoplanet, which appears to be inhabited by a single protean ocean-like entity, which takes on particular shapes in response to stimuli in ways that might suggest intelligence, but doesn’t seem able (or, perhaps, willing) to communicate with humans. However, after a reckless experiment involving bombarding the "ocean" with X rays, the men on the station are being visited by beings in the form of people who meant something to them, and clearly there is some connection with the planet, but what precisely is difficult for them to discern. Our point-of-view character, Kelvin, is haunted by a perfect copy of his late wife Rheya, who also doesn’t apparently realise she’s a copy. In between the story of the researchers trying to make sense of all of this, we get long passages of fictional academic writing in “Solarist studies”, about the planet and human attempts to understand it.

Taken as a whole, the story is a haunting and evocative exploration of human limitations: how, faced with an entity which is genuinely alien to us, we try to make sense of it in purely human terms and so never succeed in understanding. The fictional academia is credible, with authors and studies alluded to as if the reader would know who or what they are, and I appreciate an SF novel that is about a slow and considered exploration of serious concepts rather than simply action-adventure with a twist.

On a less positive note, I found all of the characters unsympathetic ciphers, and Kelvin’s relationship with Rheya has unpleasant undertones: leaving aside the fact that the reader is repeatedly presented with scenes of Kelvin treating her like an object, he doesn’t seem to consider her remotely intelligent or as having anything worthwhile to say, which suggests that their relationship might not have been a good one even if she had survived. It's a fascinating speculation on humanity's inability to comprehend the alien, but the humans in question are difficult to empathise with. Three stars.

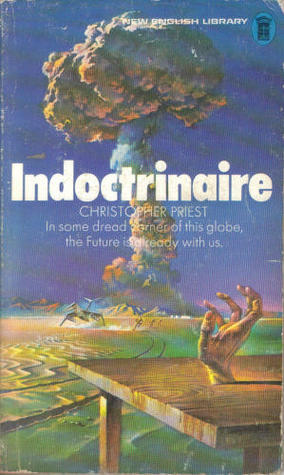

Pavlov's Prison (Indoctrinaire by Christopher Priest)

by Maureen Hogan

I first met the Journey Crew at one of their weekly gatherings to watch the TV anthology show Science Fiction Theater. I had mentioned to The Traveler I had done some writing in my college days, before packing my bags to become a librarian in the big city. He proposed that I could try my hand at something small for the Magazine, like a book review.

I was lucky to receive this debut science fiction novel from our correspondents in the UK. The work in question: Indoctrinaire by British writer Christopher Priest.

Cover Art of Indoctrinaire By Christopher Priest

The General Premise

The year is 1979. Dr. Elias Wentik has been conducting experiments on psychoactive substances at a research facility in Antarctica. There he meets two men, Astourde and Musgrove, who claim to work for the US government. They conscript Wentik to aid in their investigation of a mysterious aircraft in the Brazilian jungle. This aircraft sits inside a rip in time, where the very air itself drives people to madness. Dr. Wentik finds himself in the 22nd century, a prisoner of Astourde and his men. There Wentik must suffer through interrogations for crimes he has no knowledge of committing.

If the names and premise sound familiar, it’s not a coincidence. Fans of Impulse magazine may recognize Dr. Elias Wentik and Mr. Astourde from Priest’s short story “The Interrogator”. Fellow traveler Mx. Kris Vyas-Mall reviewed the story for the Journey’s July 22, 1969 installment, stating that “If this story [“The Interrogator”] is anything to go by, he [Priest] has a good career ahead of him”.

Potential and Pitfalls

Priest does show great potential, thematically and conceptually. Indoctrinaire is concerned with psychological conditioning and the necessity of caution in scientific pursuits. His characters are obsessed with manipulating the human mind, whether it be through chemicals in the case of Dr. Wentik, or through intimidation for Astourde. Their ignorance of the possible consequences affect the narrative in ways they could have never predicted. Additionally, Priest had novel ideas on speculative concepts. In Indoctrinaire, time travel is not achieved through vehicular means, but via force field. His projections of a hypothetical 22nd century are deeply rooted in current geopolitics and anxieties of nuclear war.

The novel boasts strong concepts but inconsistent execution. I found the Part One to drag on, preferring the pacing of Parts 2 and 3. Intellectually, I understand why Part One is the longest: it gives Priest space to create an atmosphere of dread, and at times, he excels in this. The image of Dr. Wentik scrambling in a dark labyrinth surrounded by the wails of gunfire refuses to leave my head. Other times, it falls short. Later, Astourde uses a table with a human hand emerging from it to intimidate his prisoner. The image was so surreal that it left me utterly baffled instead fearful. I feel that more selective editing would heighten Priest’s strongest scenes and maintain momentum.

Final Thoughts

I rate this book a three out of five stars. It’s obvious that Christopher Priest has great potential. I believe his narratives will grow stronger, and I’m curious to see what he comes up with in the future.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

The high rating for The Year of the Quiet Sun was very pleasing to see. I don't find that very much sf fascinates me, but this one does. The combination of credible (enough) technology, unfolding sorrow in more than one element of the story, and fascination about what happens to this republic has kept me engrossed through more than one reading already. This novel has a place in my personal canon with stories such as Budrys's novella "Rogue Moon," O'Donnell's "Vintage Season," and a few others. These are all works that anyone should be able to see were worth writing and reading and that could not have been written outside of science fiction. They justify the genre even though so much is routine or worse.

Well said. I am always impressed with Tucker, who has been breathing extra dimensions into his work since he turned filthy pro. Perhaps it's because he seems to write on his own terms—he's not pounding away at his typewriter to pay bills or fulfill contracts.