by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

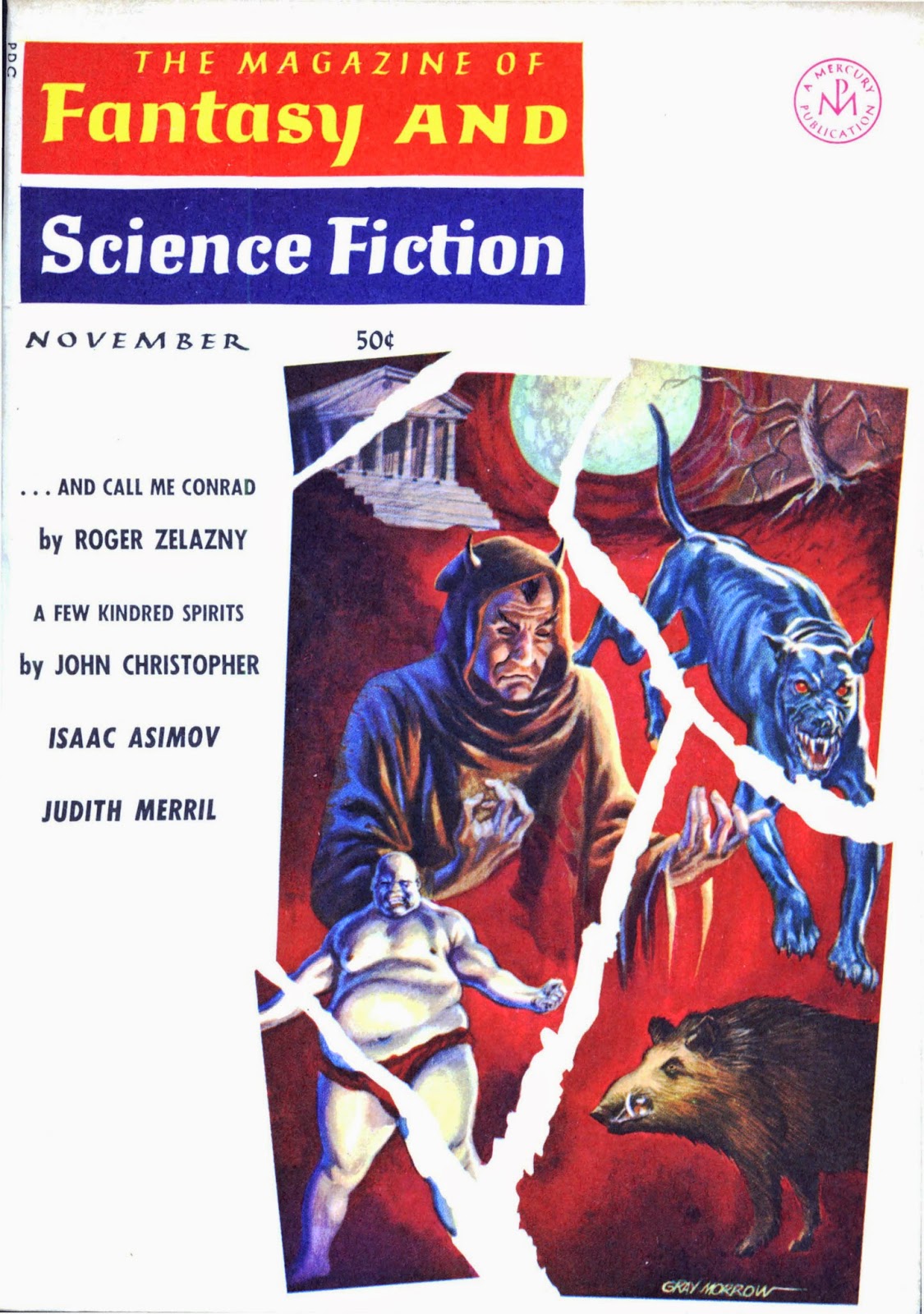

It’s that strange time of the year. I’m currently typing this a few days just after Christmas 1965 (hope it was a good one for you!), although the magazines are all dated January 1966, of course, and I suspect many of you will be reading this and the magazines in 1966!! So, whilst I’m still celebrating Christmas, and thinking back over the year gone by, we are also looking forward to new things in 1966.

It’s almost as if it was science fiction, isn’t it?

Anyway, the postman has managed to deliver me two magazines in the Christmas mail. Perhaps unsurprisingly by now, the issue that arrived first in the post this month was Science Fantasy, so I’ll start there first.

Regular readers will know that I have been moaning about these covers for a while now. As you can see, this one is cheap-looking and not reversed the trend – what is that? A tree slice? A sliver of onion? I’m almost beginning to miss those Keith Roberts covers – but wait! This is a Roberts cover, clearly one from the bottom of his artist’s paintbox.

This month’s Editorial is a little unusual. It is in the form of an open letter, with responses from Kyril, to Mr. Chris Priest, a reader who has graced the letters pages of both magazines in recent years. It immediately covers one of the issues given thought here since it was put under new management – namely, that a letter column is, to quote, “an absolute necessity.”

Using references to recent letters, Chris makes three points. Firstly, Brian Stableford’s examination of what is sf (reviewed here back in the November 1965 issue) boiled down to “it is what it is, and when it is, we know.” Secondly, Ken Slater’s letter (in the same issue of Science Fantasy ) about the literary standard of sf suggests that Kyril’s policies on this being “uncertain”. Thirdly, Science Fantasy seems to combine both modern, cutting-edge stories and yet persists in publishing ” stories that went out of vogue many many years ago.” Coincidentally, this was something I accused the magazine of last month with its publication of Harry Harrison’s Plague from Space.

Whilst I’m not sure dissecting one letter in this way is always advisable, it is interesting. The editorial is short, but Kyril replies with thought and humour.

To the actual stories.

The God-Birds of Glentallach, by John Rackham

It feels like it has been a while since we’ve seen John in either Science Fantasy or New Worlds, although he was last seen in the August 1965 issue of with A Way With Animals. I believe that he has been a regular contributor to John Carnell’s New Writings in SF in the meantime.

Here he tells us the story of Andrew Malcolm, recently-made Laird of Glentallach, who allows an archaeological dig on what is now his land and with the discovery of a mysterious box discovers that an ancient myth may have more in it than he imagined.

It is a good solid tale, which reminded me of Fritz Lieber stories in a style not that different from old issues of Weird Tales. This seems to be exactly what Chris Priest was writing about in his letter about old-style storytelling. And yet, I quite liked it. 3 out of 5.

Sealed Capsule, by Edward Mackin

And this is also the return of a veteran regular, though not seen since April 1965’s New Worlds. Sealed Capsule (a rather appropriate title considering what happens in the previous story!) is the story of what could happen if you coop up men in a sealed spaceship together for six months on the way to Alpha Centauri. Clue: it doesn’t end well, especially when you add homemade poteen and prescription medicines to the plot. Another “OK” story, which reads well but doesn’t tell the reader anything new. 3 out of 5.

“In Vino Veritas”, by E. C. Tubb

Another old hand, clearly on a roll, as he was in both magazines last month – and here he is again. We will read another from E. C. in New Worlds later, as well.

Just to clarify for the non-Latin readers, “In Vino Veritas” means “In wine, truth”, which seems appropriate for many a writer, inspired by the drinking of the stuff! Claus Heston is a writer who, in an attempt to pay his bills and clear his writers block, sets forth to use alcohol and a magic potion to help him regain his mojo. It doesn’t quite work, but there is a revelation that forms the end of the story. 3 out of 5.

The Satyrian Games, by D. J. Gibbs

A writer new to me. Johnny Collins is a reporter sent to commentate on the mysterious Annual Games on Satyrus. With the offer of a bonus, Johnny and photographer Randy Hill are prepared to spend two weeks on Satyrus, despite the rumours of danger that have been reported on before. Meeting King Kopulus, the two Terrans are treated as VIPs, which is a little unusual for reporters, until the true reason is revealed – the next day they are to be put to combat against athletic Satyrian females as a test of manhood. We find out that it is a tough life being a Breeder, and in the end the King is beaten in a competition between himself and the appropriately named Randy to copulate with as many women as possible.

In case you didn’t guess, this one reads like a satire of a substandard story from the pulps of the 1930s. If the attempt at humour is the point, it is a weak point, and clumsily done. Overall, The Satyrian Games feels like it is here as a result of the Editor’s desperation. 2 out of 5.

For One of These, by Daphne Castell

Another story by Daphne after her debut in New Worlds in October. It is noticeable how both magazines have embraced the issue of there being a lack of women writers this year.

This is a story about a baby that Anna and her mother take in after the parents are killed in a road accident near their home. In the time it takes for help to arrive, Anna becomes bonded with the infant, even though it bites her and draws blood. The revelation is then that the baby, and the parents who were killed, are aliens in disguise. The Military Intelligence team who then arrive take Anna and her family into protective custody. Anna is told that the baby alien seems to derive its food from the mother’s blood – a space vampire, if you like. (The baby is even referred to at one point as “Poor little Dracula.”)

The story ends with Anna and two other ‘nurses’ taking on the responsibility of helping feed the child, until the authorities can work out what to do, waiting for others of the same race to arrive. Solidly told, but again, nothing exceptional. 3 out of 5.

The Plague from Space (part 2 of 3) , by Harry Harrison

The second part of this serial carries on pretty much as we left off, with Doctors Sam Bertolli and Nita Mendel trying to slow down the spread of the disease in New York brought back from Space by the spaceship Pericles. At the start of this second part, Sam is rushed to Stonebridge where it is rumoured that there might be a possible cure. The rumour is sadly mistaken, but Sam finds himself in a gun battle between his team and a group of armed militia who think that their helicopter is a means of escaping the plague.

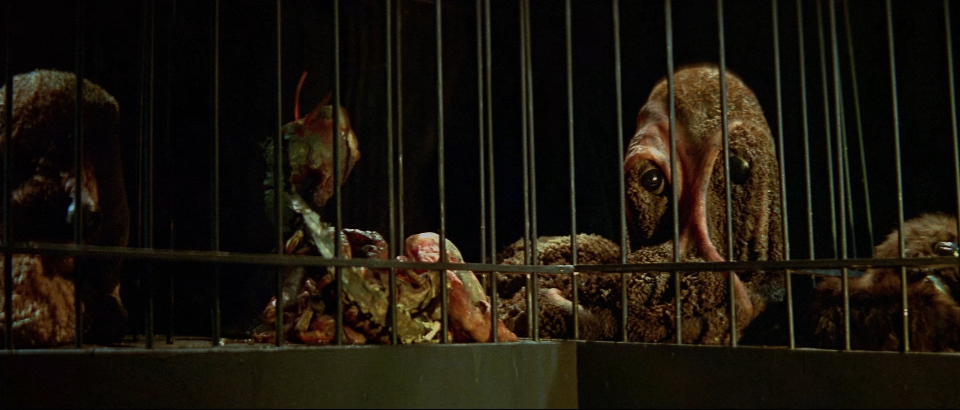

Eventually returning back to the city, Sam is contacted by Nita, who tells him that the disease is mutating and that the samples they have previously taken do not survive in Jupiter-like conditions. The point is that the disease seems to be human-based and is mutating to infect other animals, such as dogs.

Sam and Nita find themselves side-lined for political reasons, so in protest they sneak themselves into an United Nations World Health meeting. There a decision is made to quarantine and then cleanse the worst part of the city by dosing it with radioactive material, leaving nothing alive.

Lots of running about and, as is typical for a middle part of a story, lots of exposition. Like last month, a tale told well but with little to elevate it to best-seller material. 3 out of 5.

Summing up Science Fantasy

Science Fantasy continues to play safe this month, continuing to rely on regular seasoned writers. Looking at the names returning, it is almost as if editor Kyril has fallen back on old ways and simply lifted work in the slush pile from writers from the old-school Carnell-era New Worlds. This may be intentional, but the overall impression I get is that of a magazine in a holding pattern, seemingly determined not to move forward. Surprisingly mundane.

The Second Issue At Hand

The editorial this month takes as its contentious starting point the idea, from James Colvin’s serial, that Science is the New Religion, before going further to say that in this wonderful world of the New Wave writing we are currently in, Science is the only prism through which Man can focus upon his future hopes and fears. It is a bold and deliberately argumentative point, but one which seems rather old-fashioned. I’m sure it was a point being made back in the early years of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells. Nevertheless, it is a discussion made with passion and enthusiasm.

To the stories!

The Wrecks of Time (Part 3 of 3)), by James Colvin

Last month’s part of this serial was clearly a middle part, all rushing about with no resolution. In this third and final part, Professor Faustaff and his faithful friends have appeared on the newly-created Earth Zero, with his enemies Steifflomeis and Cardinal Orelli.

Here the story becomes even more fractured and diluted. On arriving at Earth-Zero, Steifflomeis attempts to rally Faustaff to his cause but is turned down. There is a standoff between Faustaff’s team and Orelli’s men before Faustaff, with Nancy Hunt and Gordon Ogg, escapes in a car. They reach what appears at first to be a garbage dump but is actually made up of new-looking but random objects from different times – an arquebus, a Chinese kite, a Fokker triplane, for example. Presumably these are the "Wrecks of Time" of the title?

Faustaff realises that Maggy White may be the answer to his problems. Like Steifflomeis she appears to be working for the Principals, a set of immortals who created the multiple Earths and now seem to be involved in some sort of multidimensional game across Space and Time.

This also explains the increasingly bizarre nature of the story. Faustaff returns to Orelli’s cathedral to find Orelli crucified, symbolising the death of Religion that Moorcock talked of in his Editorial. Steifflomeis explains that this is part of an Activation Ritual that all of the newly-formed planets must go through. These appear to Faustaff in a dream-like state.

Faustaff sees a ritual sacrifice, a symbolism of the primitive people’s fears and wishes. He chases after Steifflomeis to find Maggy Smith in some kind of medieval-esque Queen of Darkness ritual. Nancy and Ogg are elsewhere in another ritual, in Hollywood, which causes Faustaff to laugh at the ludicrousness of the situation, to which I could only agree. Steifflomeis reappears and challenges Ogg to a duel.

The story at this point seems to make little sense, although there is an attempt to point out that the rituals seem to be repeated dream-like events needed as simulations for the principals to activate the planet. Maggy kills Steifflomeis, as he is blamed for the failure of this activation. Leaving the team at a hospital to tend Orelli, Maggy then takes Faustaff to meet the principals. We finish with a huge exposition as the principals explain the reasons for the simulations, although at this point I was beginning to lose interest. It seems that all of this is some cosmic joke. However, there is a happy ending.

After a great start and a lot of potential, this series appears to end with a confusing jumble of increasingly erratic sequences and an all-too convenient solution. A lot of noise but despite the author clearly thinking that it has, not a lot of sense. 3 out of 5.

The Case, by Peter Redgrove

Oh, God – poetry. Perhaps one of the most underwritten and over-appreciated forms of the English language, the first page made my heart sink. But I need to put my personal prejudices aside, and I do think that it is good to see the magazine push the boundaries a little and include something a bit different this month. Even if it is not to my own tastes. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by David Kearn

The Failures, by Charles Platt

Another regular author this month. It is very brave to title a story The Failures, isn’t it? It is almost as if it is taunting me to say something like how much of a failure this story is. Well, it’s not quite as bad as all of that. But it didn’t entirely work for me.

It seems to cover similar ground to Platt’s recent story The Lone Zone, , in that it deals with disaffected young adults. Last time it was some kind of future apocalypse, this time it is about the near future, although it is full of things from the present as well. Greg meets Cathy Grant at a Press party for his band, the Ephemerals. At first glance it all seems good – fast car, music being played on the radio, nice clothes. However, as the story crawls through a simulacrum of 1960s culture with its litany of dodgy characters, drugs, bad sex and a never-ending search for thrills, the point seems to be that such a seemingly luxurious life can end up being monotonous and unfulfilling, Really, life is awful and there’s nothing you or I can do about it. All rather depressing, which I suspect is the point. 3 out of 5.

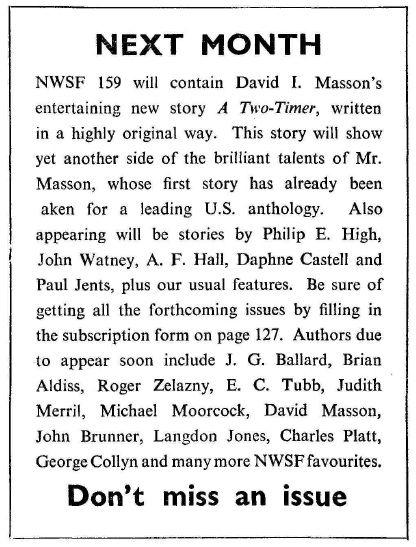

Love Is an Imaginary Number, by Roger Zelazny

This is perhaps the story I was looking forward to reading most this month. American Roger has been blazing a trail over with you in the States and seems to be seen as an American writer firmly coming to grips with what we are calling ‘the New Wave’. His writing, what I have read of it so far, is usually imaginative, intelligent and deals with those themes of the softer sciences and inner space so beloved of the new breed of writers.

Like Charles Platt’s story, this is another one that begins in a seemingly positive manner. It is a fast-paced story of an unnamed character, told in the first person, who escapes from a prison and his jailor Stella. A renegade who runs across different landscapes, chased by villains who want to do him harm. In the end, he is bolted down and tortured.

In precis this story sounds like a lot of others. What such a summary doesn’t show is the way the prose is written – a dazzlingly precise yet grandly lyrical piece of writing that pulls you in and doesn’t let you leave until the end. This, when compared with the Colvin story, showed me what a dazzlingly prosed chase story could be like when combined with a plot that feels like a Greek myth combined with a Fantasy plot. As good as I hoped it would be. 4 out of 5.

Mouth of Hell, by David I Masson

And this is the other story I was looking forward to reading this month. David made quite an impression on me with his startlingly clever story Traveller’s Rest in the New Worlds issue of September 1965. This is quite different, yet just as brilliant. It is a story of an expedition to a place initially unknown but seems like somewhere we know. It reminded me a little of Lovecraft’s In the Mountains of Madness, but as the story progresses it becomes more science fictional. The expedition continues to traverse a continuous down-slope, first with vehicles and then on foot. The three expeditioners who continue – with the great names Mehhtumm, ’Ossnaal and Ghuddup – experience many challenges with increased heat and pressure. ‘Ossnaal has a fit and upon a rescue attempt one of the group is killed and another goes missing.

The next day, another trio, led by the team leader Kettass but with oxygen, manages to get further, but the death of another of the team leads to the search being abandoned.

There is then a couple of postscripts. Five years later Kettass returns with two VTOL craft and descend into the abyss, filming for a documentary. Their first attempt is deeper, yet defeated. On the second attempt one of the vehicles is crushed by the pressure 25 kilometres down and the second expedition is halted.

Thirty years after that. Kettass, now a septuagenarian, is taken down via pressured cable railway. The story ends by explaining that despite further deaths the area will eventually become a tourist resort with a game reserve and a sanatorium. Technology and Man’s endeavours have eventually tamed the challenges of the mysterious hole.

I love the fact that this is so different to Traveller’s Rest and yet so good. It may not be quite as unique as Traveller’s Rest was, but it is literate and memorable, with an unusual setting. This is a Boys Own adventure story rewritten for intelligent adults. 4 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Anne, by E. C. Tubb

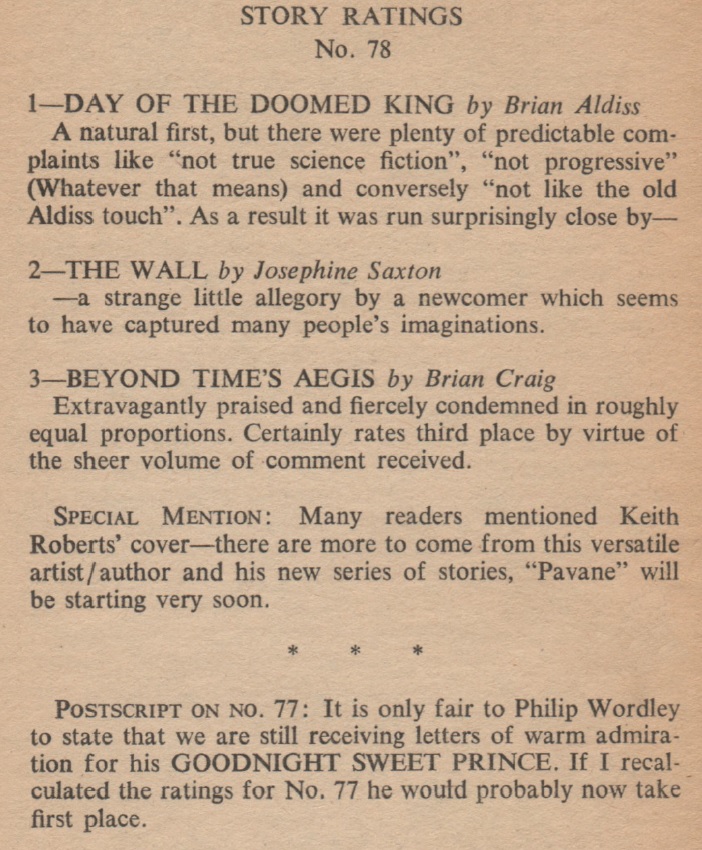

What’s this? Another story by the prolific E. C. Tubb? This is a brief yet memorable story, written in a different style to his usual about a dying Warrior in his also dying spaceship who in his pain dreams of a different place, with Anne. It made me think that it was a science fictional version of the Brian Aldiss story The Day of the Doomed King, back in the November 1965 issue of Science Fantasy. 3 out of 5.

Book Reviews, Articles and Letters

Them As Can, Does, by John Brunner

Oh, look – an article from Mr. Brunner, after his allegedly impressive sparring with John W. Campbell at the recent Worldcon.

Fellow traveller Gideon has suggested before that there are two or three types of Brunner writing that we see. So, which Brunner do we have here? It is perhaps a little unfair to use such comments on a non-fiction article about how to get published. But the article is faintly amusing, makes its point well with some dignity and some sardonic wit that feels like it is based on experience. It can be summed us as “It’s not easy.” 3 out of 5.

Book Reviews

And so after the serial, we now get the Book Review. James Colvin reviews Bill, the Galactic Hero with the sort of praise expected from the editor of the magazine himself. Colvin also weirdly reviews himself when he reviews Mike Moorcock’s The Fireclown. This can be a little confusing, especially when Colvin takes Moorcock to task for some of his writing, as he does here.

I can’t help feeling that Moorcock is laughing at us as he does this, although I guess that those of us in the know about such things may find it rather irreverent and amusing.

In the letters pages there is a point made about the price going up being a good thing but that there should also be more short stories and less serials, which can be bought as novels at anytime. The second letter suggests that as Analog is “the engineer’s magazine”, then New Worlds is “the undertakers’ magazine”, such is the magazine’s preoccupation with gloom and death. Must admit that I don’t entirely disagree with that one – it is something I’ve noticed myself recently.

Summing up New Worlds

Having said that the last issue of New Worlds was unmemorable, this one is a considerable improvement. The Zelazny story is great, as is the very different Masson story, which is perhaps my favourite story of the month.

I should give credit for the poetry, even when I didn’t like it. There are still a few of the regular contributors as well, but I am pleased that this is a step in the right direction, pushing the genre whilst at the same time maintaining some connections to the past.

Summing up overall

And with that, it should not be a surprise that the ‘winner’ this month for me is New Worlds.

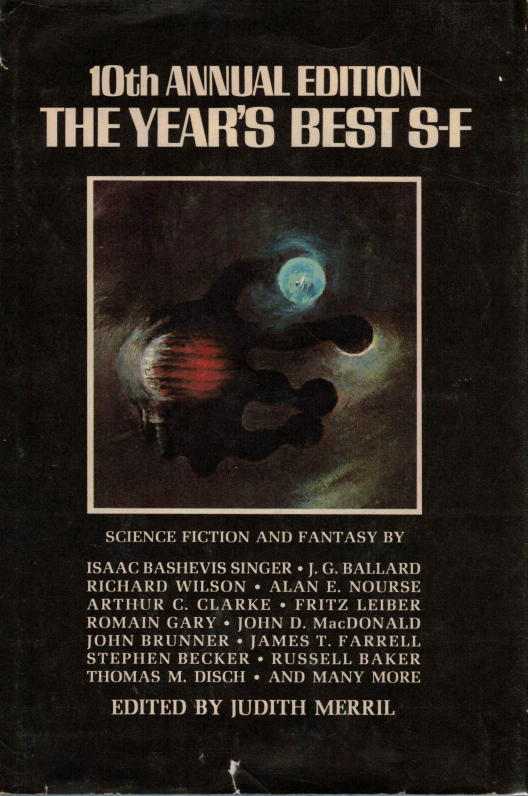

With Christmas just gone, it means that I must wish you all the best for what is left of the Festive season and indeed for the New Year. 1965 has been shown to be an interesting one for the Brit magazines and despite my grumbles I can’t see 1966 being any different. (If you haven't seen it yet, Judith Merril makes some astute comments about it in this month's Magazine of Fantasy & SF that are worth a read.) Here’s hoping!

Until the next…

![[December 28, 1965] God-Birds and Dreams <i>Science Fantasy</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, January 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Science-Fantasy-NW-Jan-1966-672x372.jpg)

![[December 26, 1965] Murders per Minute (James Bond in <i>Thunderball</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651226poster-609x372.jpg)

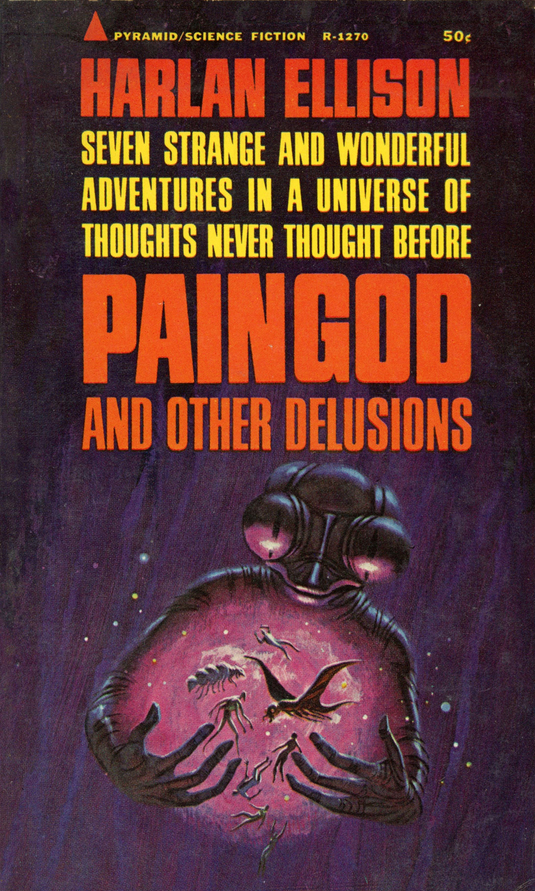

![[December 24, 1965] Gallimaufry <i>du Saison</i>(<i>The Year's best Science Fiction</i> and <i>Paingod and Other Delusions</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651224covers-672x372.jpg)

![[Dec. 22, 1965] Swann Lake (the 1965 Galactic Stars)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651228stars-505x372.jpg)

![[December 18, 1965] Bulges and Depressions (January 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651216cover-672x372.jpg)

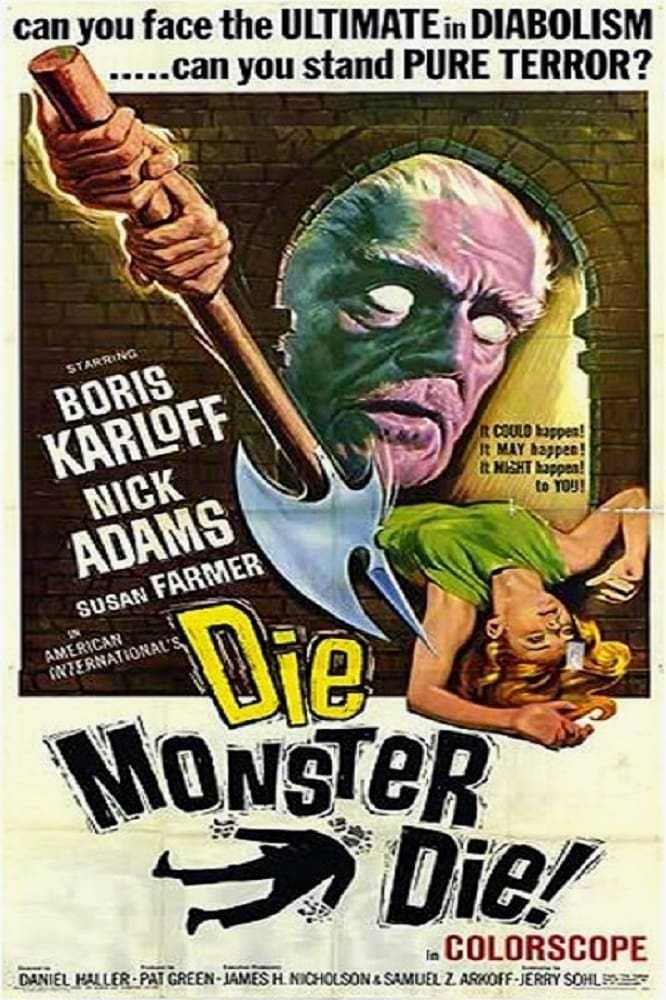

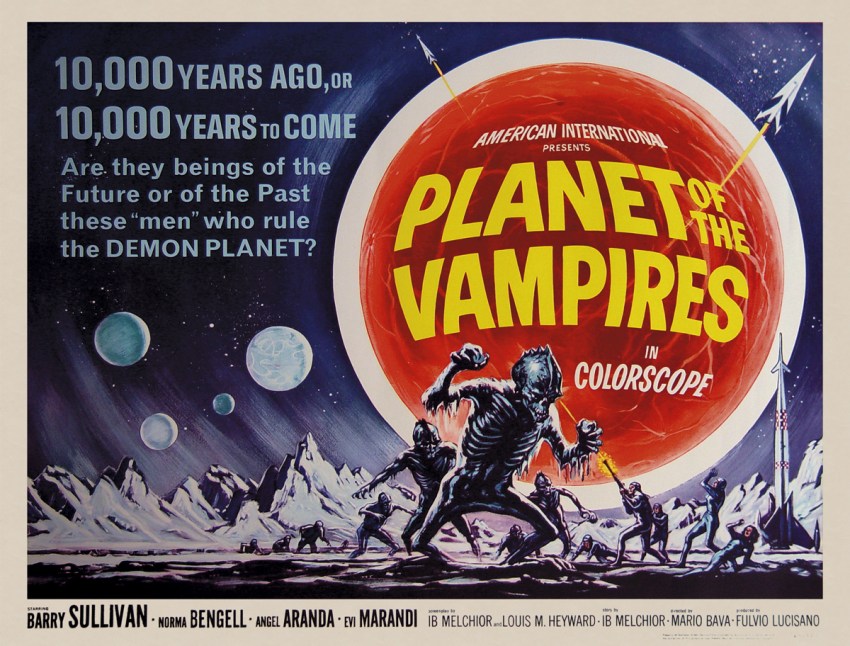

![[December 16, 1965] Two Creepy Terrors (<i>Die Monster Die!</i> and <i>Planet of the Vampires</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/karloff-672x312.jpg)

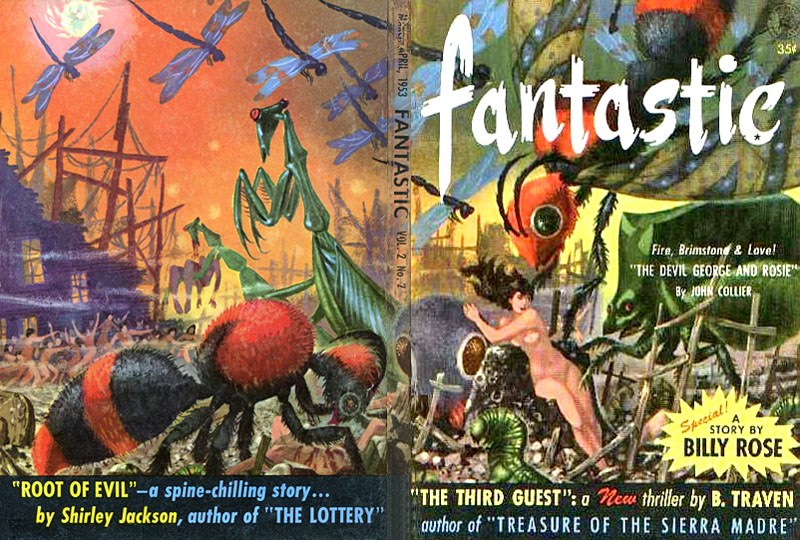

![[December 14, 1965] Expect the Unexpected (January 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Fantastic_v15n03_1966-01_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

![[December 12, 1965] Something Old, something New (<i>The Bishop's Wife</i> and <i>A Charlie Brown Christmas</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651212feature-672x372.jpg)

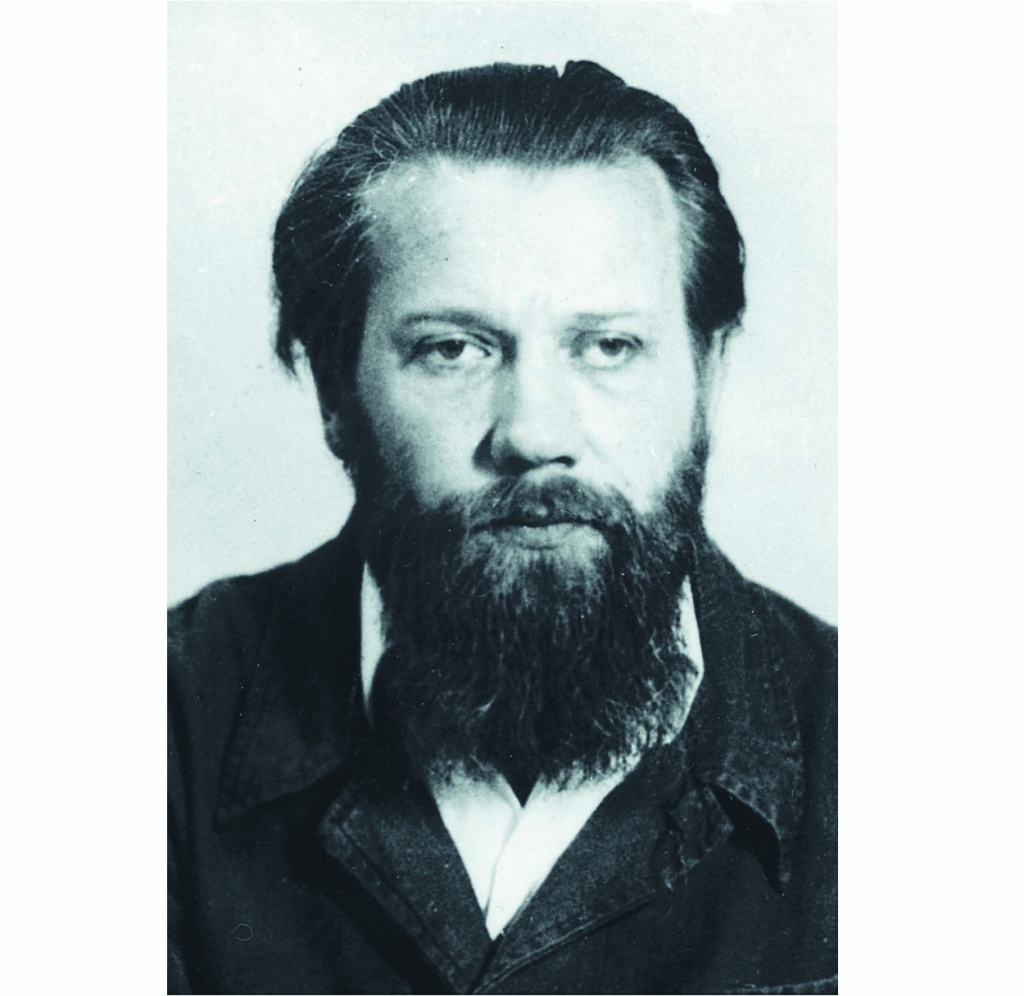

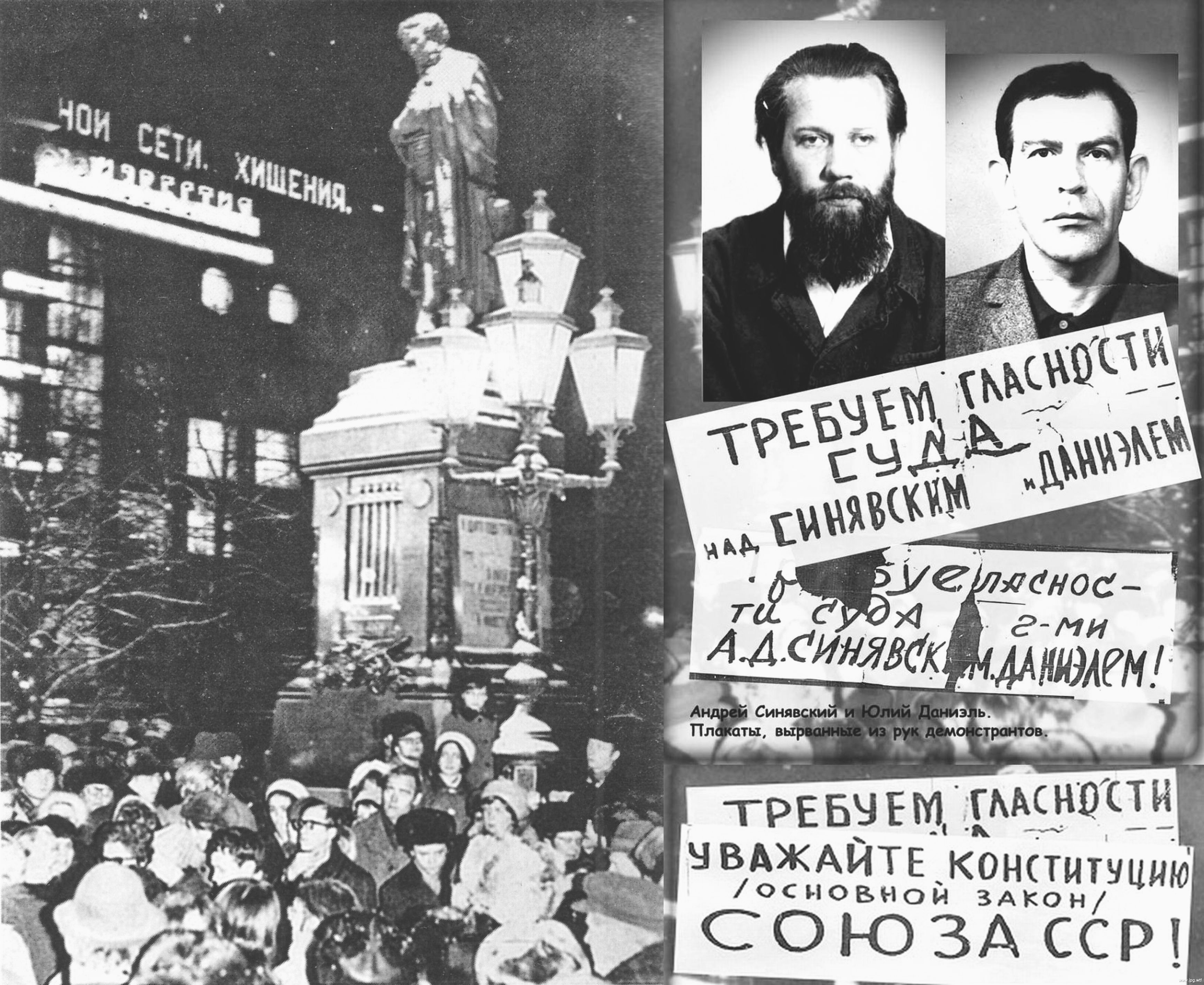

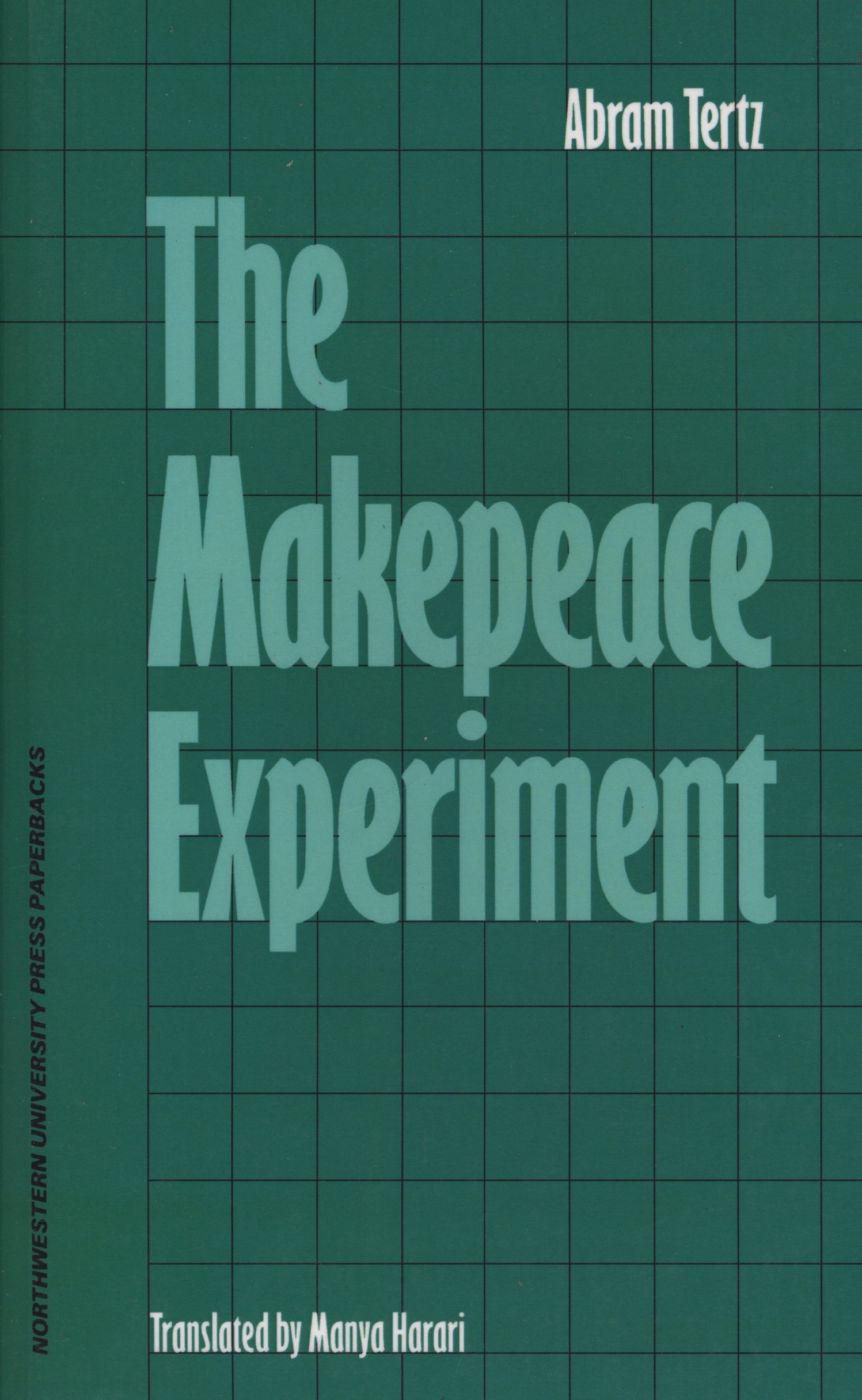

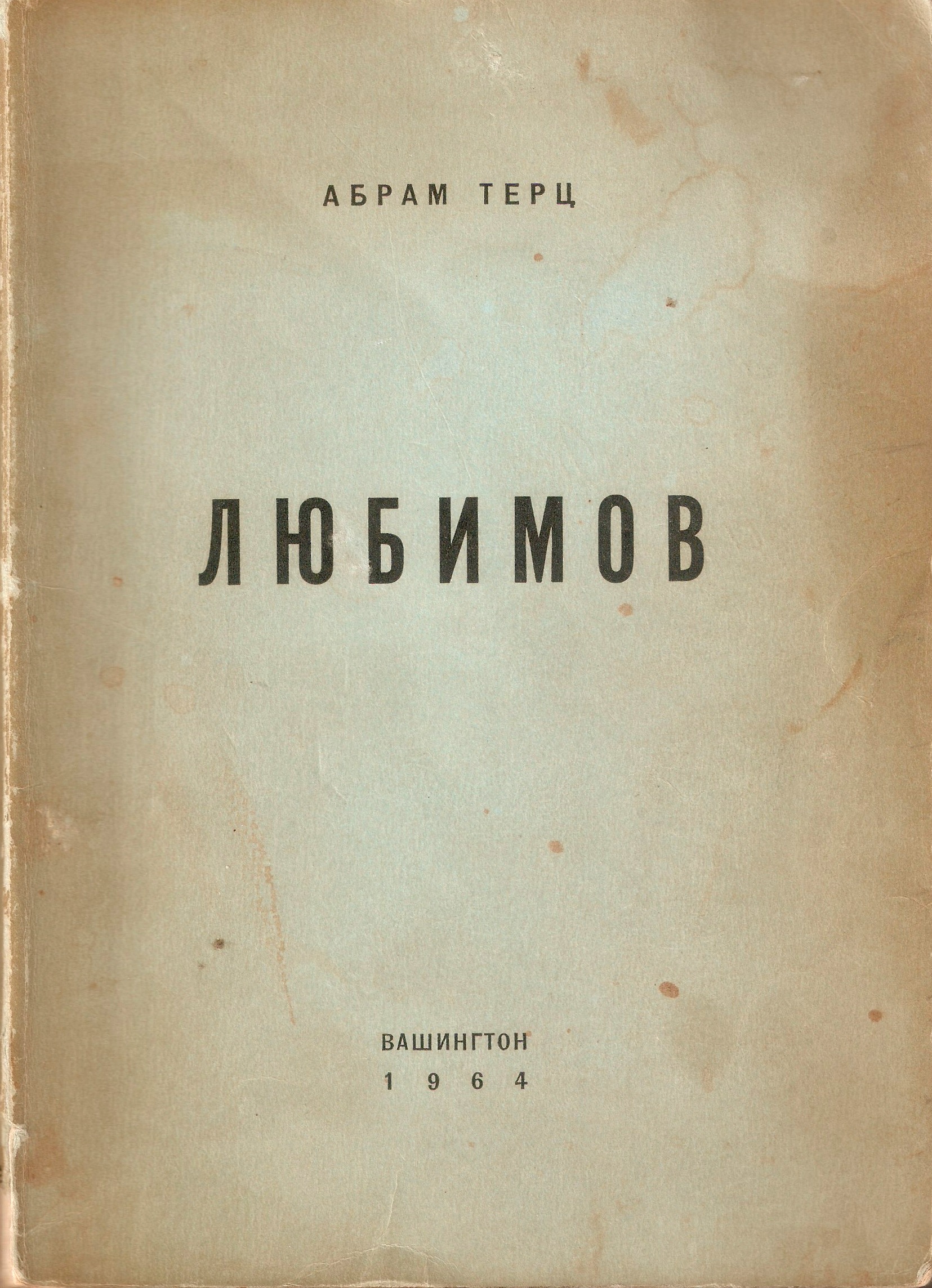

![[December 10, 1965] For the People, By the People <i>The Makepeace Experiment</i>, by Andrei Sinyavsky](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651218Makepeace-Experiment-672x372.jpg)

![[December 6, 1965] Are You Sitting Comfortably? Then I'll Begin (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Daleks’ Master Plan [Part 1])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651206dalek-672x372.jpg)