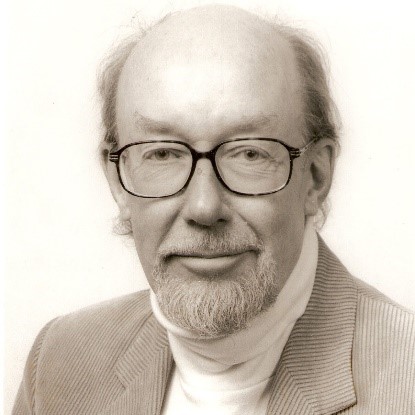

by Gideon Marcus

Five against Arlane, by Tom Purdom

As you may know, I am a big fan of Tom Purdom. He's a very nice fellow, and his first book, I Want the Stars, was a stand-out. Thus, I was quite excited to see that the new Ace Double at the local bookstore featured my writer friend.

The first two chapters do not disappoint. We are thrown into the action as Migel Lassamba (explicitly of African descent; no lily-white casts in Tom's books) holds up a rich man and his personal doctor. His goal: to get an artificial heart for his companion and love, Anata. Why doesn't he just get one for free from the government hospitals? Because Migel, Anata, and three others are rebels whose goal is to topple Jammett, dictator of the planet Arlane. Five against Arlane, you see?

Thus ensues a ever-widening conflict between the outnumbered but canny rebel troops and Jammett, who resorts to increasingly draconian methods to retain control. His biggest ace in the hole is his ability to slap mind-control devices onto citizens. These "controllees" are fully conscious, but their bodies belong to the dictator, obeying his every whim. As Migel's cadre begins to turn the tide against Arlane's leader, the abuse of the controllees gets pretty grim.

There's a lot to like about this book. Arlane is a nicely drawn world, mostly tidally locked so its days last forever and only the pole is inhabitable. The descriptions of technology and society are largely timeless. Purdom is excellent at conveying material that will not be dated in a decade. As in Tom's other stories, we have intimations of free love and even polygamy/andry, and there is no real distinction between sex or race.

Sadly, where the book falls down is the execution. After those exciting first chapters, the chess-like contest between the rebels and Jammett feels perfunctorily written, as if Tom had to get from A to C, and he wasn't particularly interested in writing B. It almost reads like a chronicle of a homebrew wargame (ah, what a wargame this novel would make!) If I'd been the editor, I'd have sent it back and asked for…more. More emotion. More characterization. More reason to feel invested. And a more fleshed out ending (but perhaps that was a fault of the editing, not the writing).

I noted that the weakest parts of I Want the Stars and Tom's latest short story, Reduction in Arms, were the curiously detached combat scenes. Where Tom excels is the thinky bits. I suggest he either work harder on the fighting pits, or stick to thinky bit stories (like his excellent Courting Time).

Three stars.

Lord of the Green Planet, by Emil Petaja

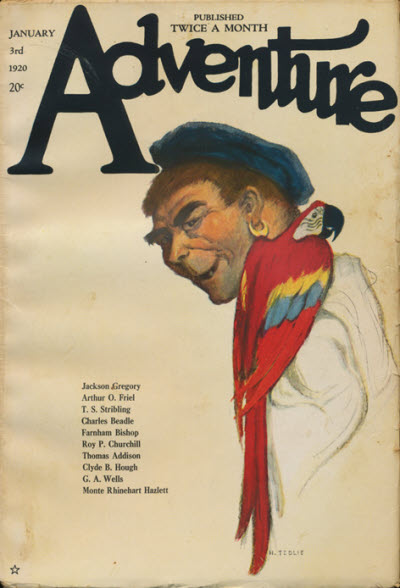

Emil Petaja is a new writer perhaps best known for his science fiction sagas based on the Karevala, the Finnish body of mythological work. Now, Petaja plumbs Irish myth for this truly strange, but also rather conventional science fantasy.

Diarmid Patrick O'Dowd (a fine Jewish name) is a scout captain for X-Plor, Magellanic Division. His flights of exploration frequently take him close to a mysterious, green-shrouded object. Finally unable to resist, he becomes the first of his corps to pierce the viridian veil. His ship crashes and disintegrates, leaving him stranded in a Celtic nightmare. On one side, the towers of the islands, inhabited by Irish lords whose beautiful works are created on the backs and tears of countless generations of peasants. On the other, the fetid swamps of the Snae–froglike magicians who seem to predate the human colonists. And up in the tower of T'yeer-Na-N-Oge resides the Deel, Himself, who rules over the world with a song whose lyrics none can deviate from, enforced by a panoply of beasts, flying, swimming, and creeping.

Of course, there is a personal element as well. The beautiful but utterly rotten-hearted Lord Flann plans to unite the islands and lead a crusade against the Nords. But first, he would marry his fair and kind cousin, Fianna. Fianna, on the other hand, has other designs. After rescuing Diarmid upon his arrival, she falls for the fellow, teaches him swordplay, and helps him fulfill his geassa to save the planet from the domination of the Deel. Along the way, there is plenty of swashbuckling, mellifluously articulate sentences, weird foes, and a twist.

It's pure fantasy, more akin to Three Hearts and Three Lions than anything else. But it's fun. And it has warcat steeds (Purdom's book has watchcats–I guess oversized felines are in this year).

Three and a half stars — and I'll wager Cora and/or Kris would give it four.

Triads

by Victoria Silverwolf

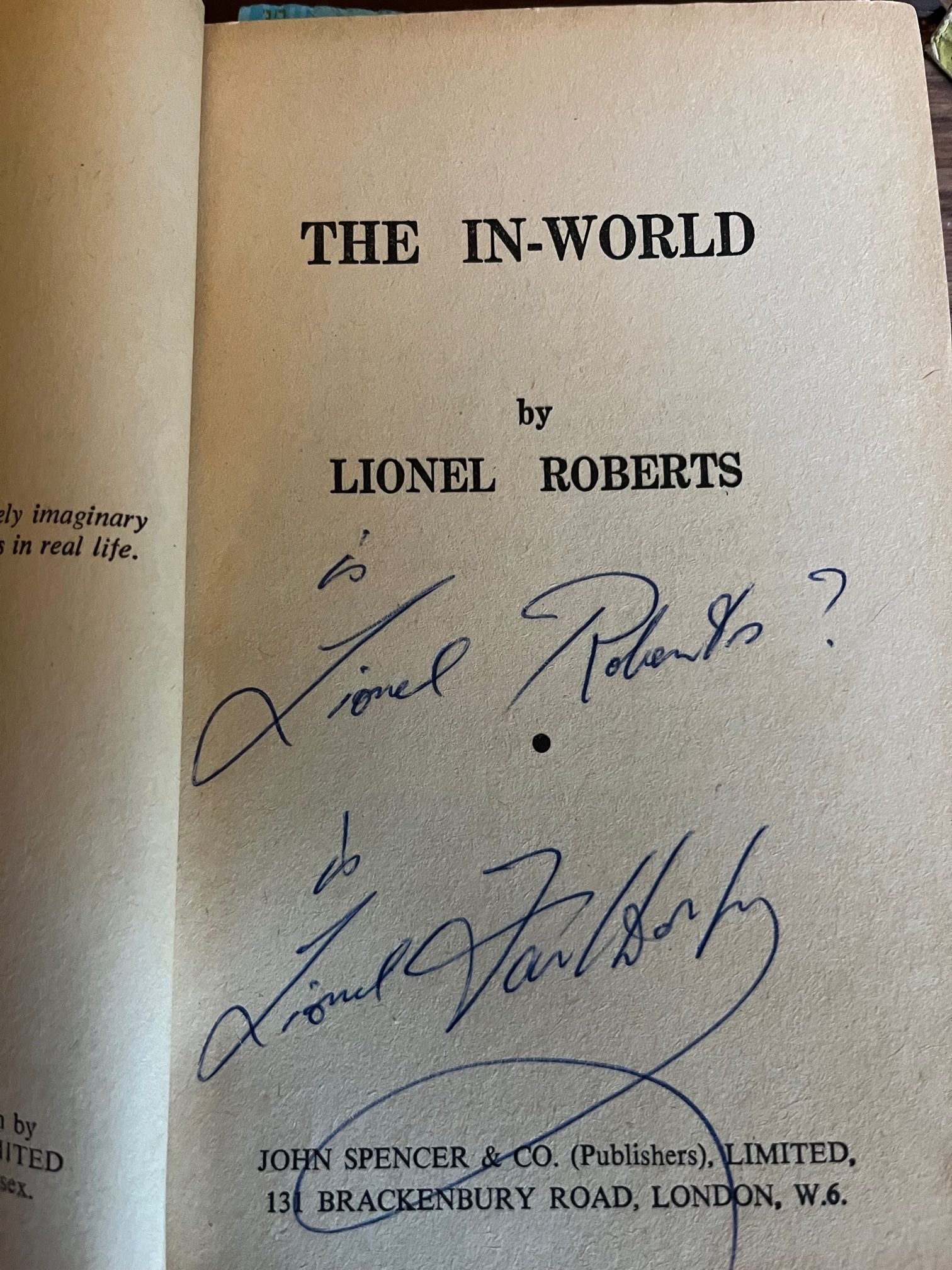

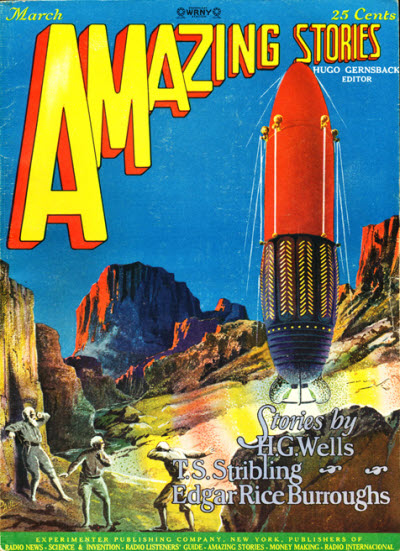

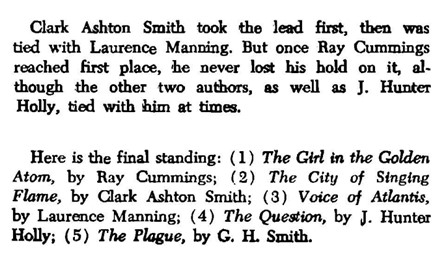

Two new science fiction novels deal with the relationships among three characters. As we'll see, in one of these the trio is very intimately connected. First of all, however, let's take a look at the latest book from an author known for prolificity.

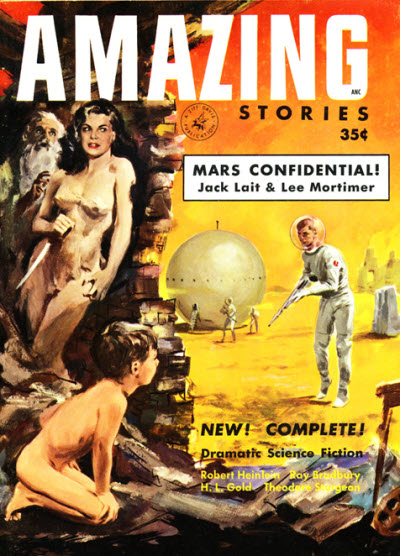

Cover art by Robert Foster.

The novel begins and ends with the same words, spoken by two very different characters and having different implications.

Pain is instructive.

In this way, the author announces his theme from the very start. Thorns is all about suffering. Physical pain, to some extent, but, more importantly, emotional pain.

Duncan Chalk is a grotesquely obese, incredibly rich man who controls just about all forms of entertainment throughout the solar system. Secretly, he is also a kind of psychic vampire, feeding off the misery of others.

Minner Burris is a space explorer who, against his will, was surgically transformed by aliens. His two companions died during the procedure and he barely survived, monstrously changed outside and in. As a result, he is a loner, seen as a freak by other people.

Lona Kelvin is a teenage girl who had a large number of her ova removed and fertilized outside her body. The resulting babies were developed inside other women, or in artificial wombs. Although her physical appearance remains unchanged, the resulting publicity made her as much of an outsider as Minner.

Duncan's plan is to bring these two miserable people together, both as a form of voyeuristic entertainment for an audience of millions and to feed on their suffering. To win their cooperation, he promises to give Minner a new body and to allow Lona to raise two of the infants produced from her eggs as her own children.

At first, the pair simply share their mutual pain, sympathizing with each other. As Duncan sends them on a luxurious vacation to all the pleasure spots in the solar system, they become lovers. As he predicted, however, their differences soon lead to ferocious arguments. Minner sees Lona as an ignorant child, and Lona comes to hate Minner's bitterness and anger. Can they escape from Duncan's scheme, and find some kind of peace?

Reading this book is an intense, almost overpowering experience. It is the most uncompromising work of science fiction dealing with human suffering since Harlan Ellison's story Paingod. Although set in a semi-utopian future, the settings — a cactus garden, Antarctica, the Moon, Saturn's satellite Titan — are almost all stark and bleak. There are other characters I have not mentioned — an idiot savant, abused by his family; the widow of one of Minner's fellow astronauts, obsessed with him in a masochistic way — who offer more examples of the varieties of pain.

In addition to offering a vividly described, detailed future, Silverberg writes in a highly polished style, full of metaphors and literary allusions. I believe this is his finest work since the outstanding story To See the Invisible Man. With this novel, and his highly praised novella Hawksbill Station, I think we're seeing a new Silverberg, adding greater sophistication and more serious themes to his inarguable ability to produce an unending stream of fiction.

Five stars.

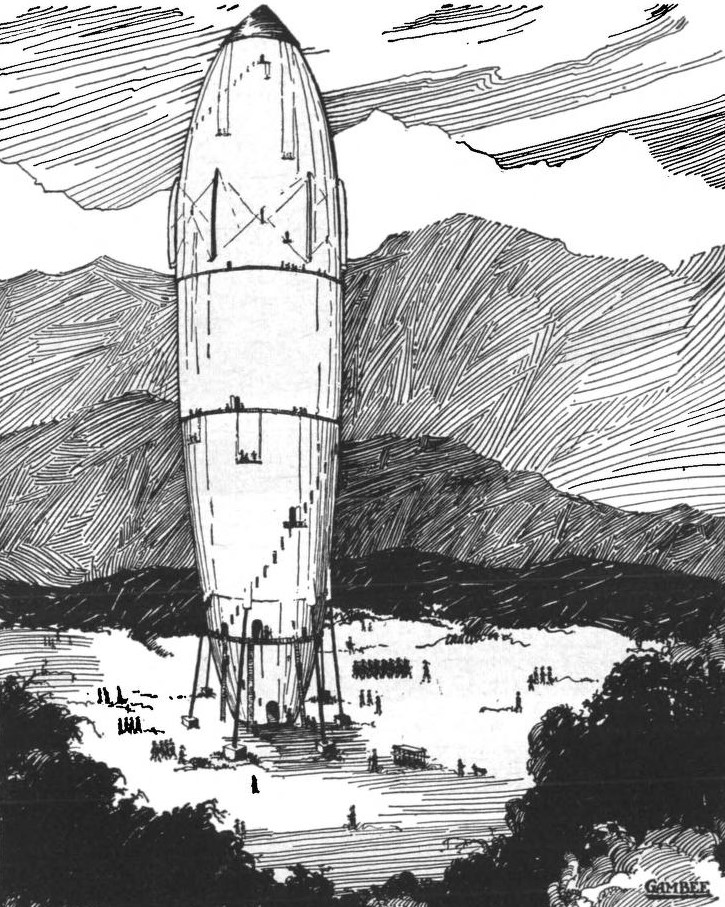

The Werewolf Principle, by Clifford D. Simak

Cover art by Richard Powers.

Andrew Blake is a man with a problem. First of all, that's not even his real name. He picked it at random.

You see, Andrew (as we'll call him in this review) was discovered in deep space, after having been in suspended animation for a couple of centuries. He has no memory of his past, although he is familiar with Earth the way it was two hundred years ago.

In order to discuss this novel at all, I need to talk about something that the author reveals about one-third of the way into the book. I don't think that gives too much away, but if you'd rather dive into it without knowing anything about the plot you should stop reading here.

Still with me? Good.

Andrew is actually an android, an artificially grown human being with a mind taken from another person. He was designed to copy the mental and physical forms of aliens he encountered while exploring other star systems. The idea is that he would record this information, then revert to his previous condition. It didn't quite work out that way.

Andrew shares his mind with two other beings. One is a wolf-like alien, although it has arms that allow it to carry things and manipulate objects. The other is a sort of biological computer, a relentlessly logical entity that often takes the form of a pyramid.

Andrew's body changes shape, depending on which mind has control. After a brief period of confusion, during which these alterations happen at random, Andrew recovers some of his memory. The three minds and bodies work together, evading the folks who think he's some kind of monster.

There's a lot more to this book than the basic plot. Simak throws in a lot of futuristic details. Notable among these are talking, flying houses, and aliens who are essentially the same as the brownies of folklore.

Not all of these concepts mesh together smoothly, although they provide proof of a great deal of imagination. The overly solicitous robot house offers some comic relief, and the so-called brownies may seem too whimsical for some readers. Otherwise, the novel is quite serious, even offering a mystical vision of the unity of all life in the universe.

My major complaint is a plot twist late in the book, revealing the true nature of a character I haven't even mentioned. It comes out of nowhere, depends on a wild coincidence, and creates an artificial happy ending.

Despite these serious reservations, I actually liked the novel quite a bit. It's not a classic, but it's well worth reading.

Three and one-half stars.

![[August 12, 1967] Planetary Adventures (August 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670812covers-672x372.jpg)

![[August 10, 1967] Badger Books: A Farewell and an Introduction](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/IMG_6354-672x372.jpg)

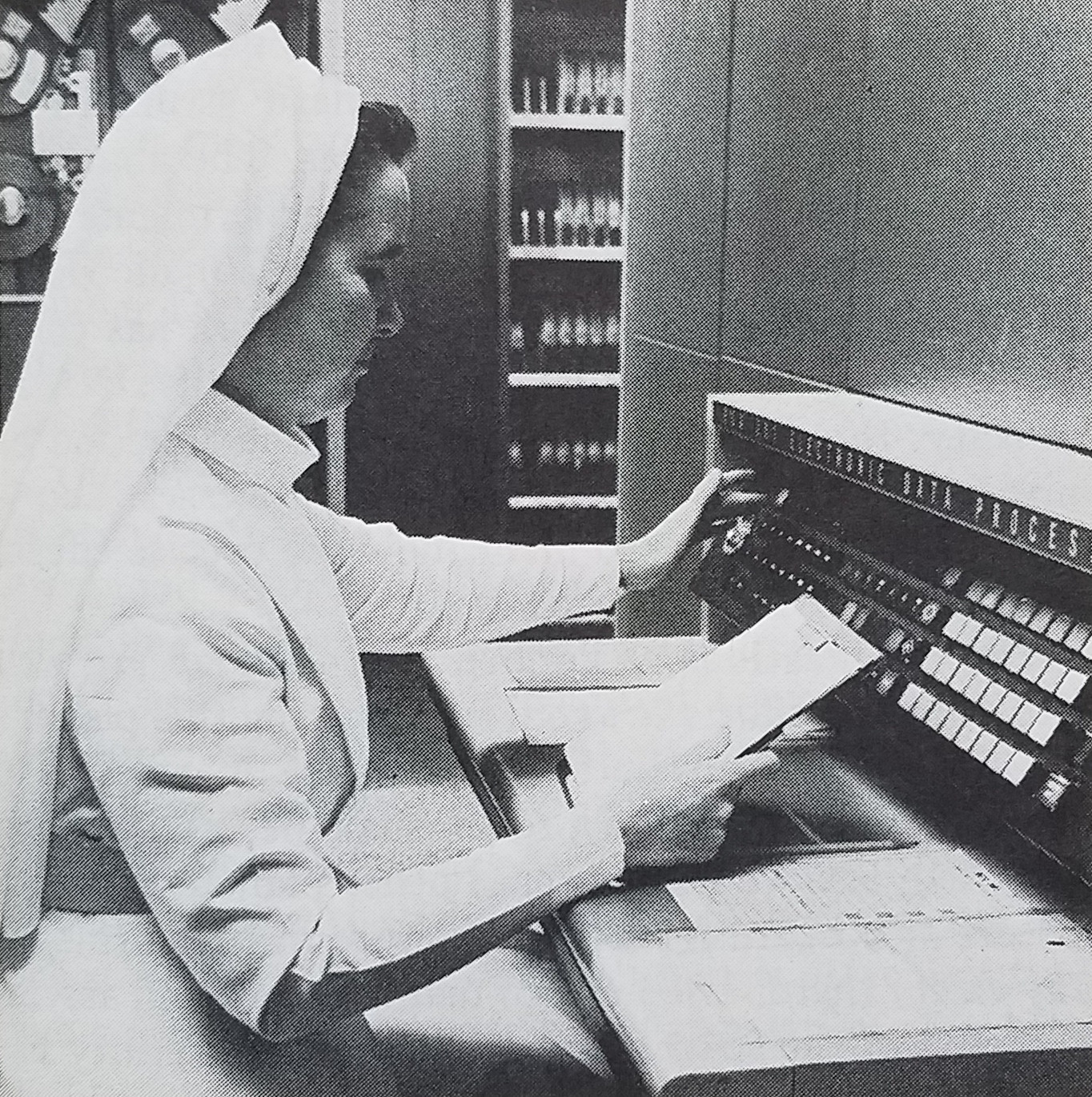

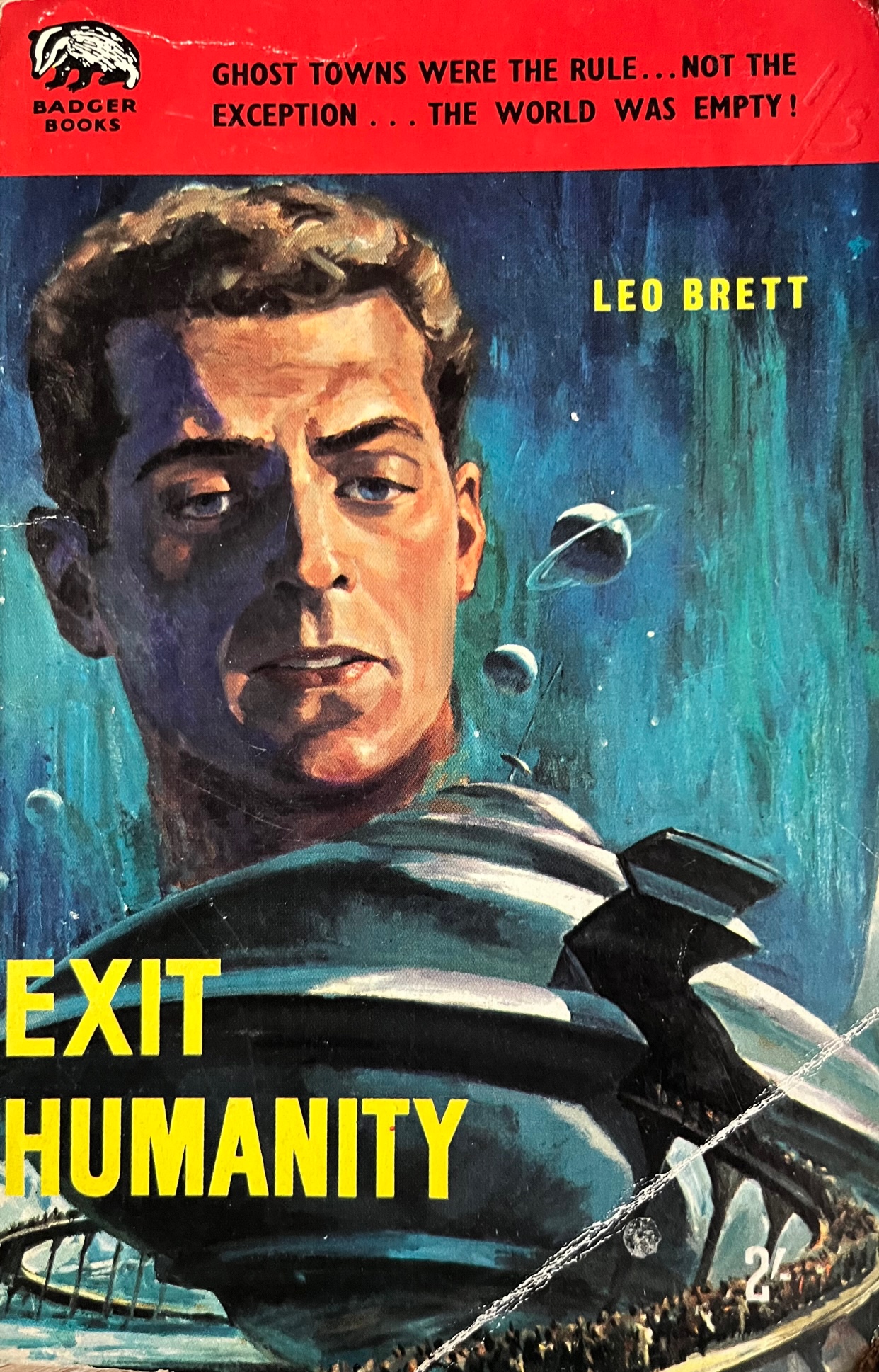

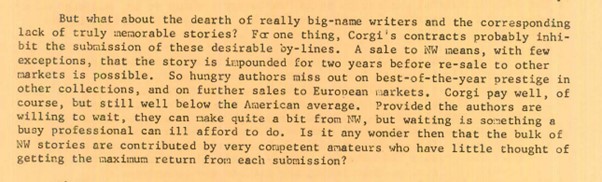

This is what we're losing.

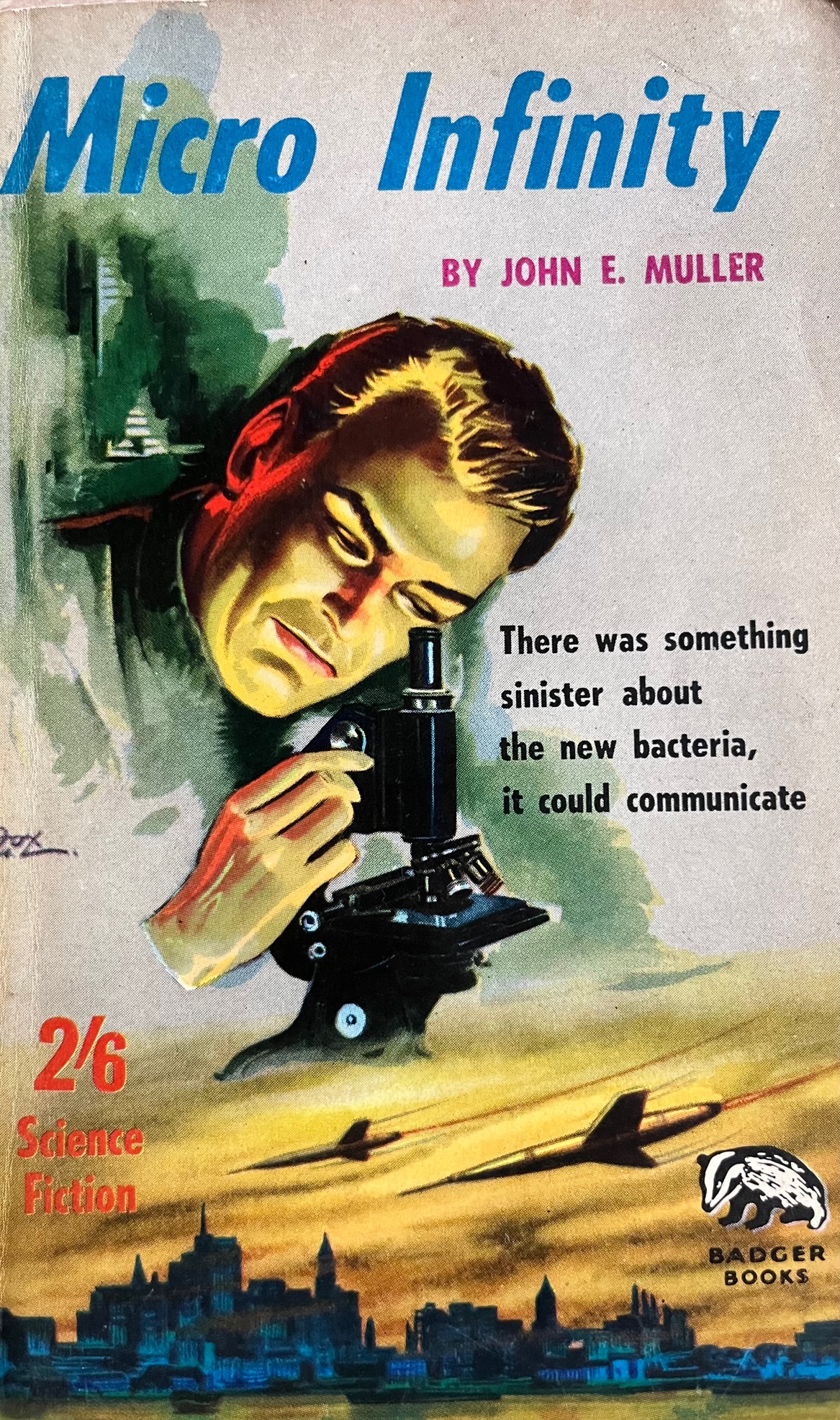

This is what we're losing. Even Mr Fanthorpe isn't always sure who he is

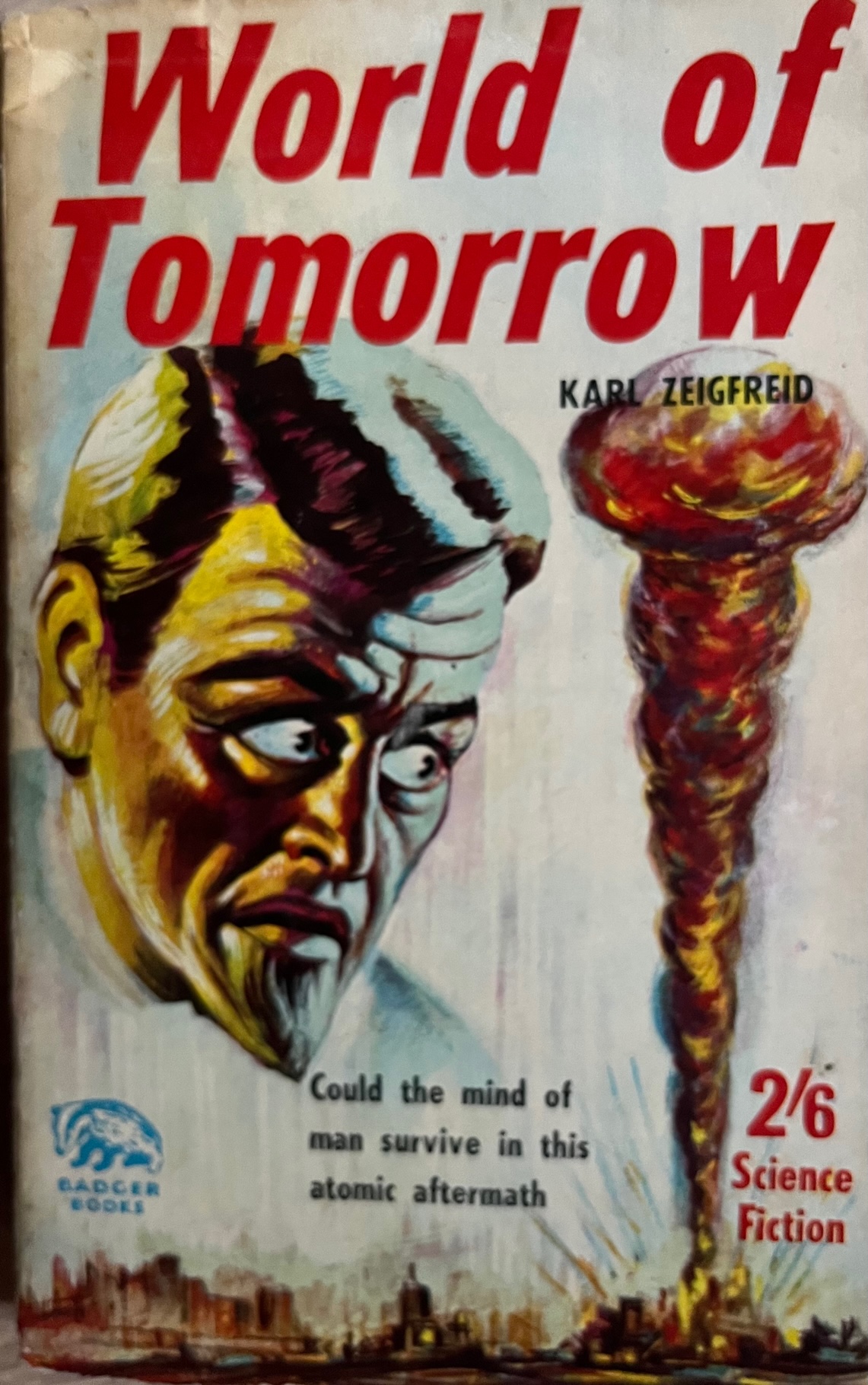

Even Mr Fanthorpe isn't always sure who he is Knowledgeable readers may be able to identify the source.

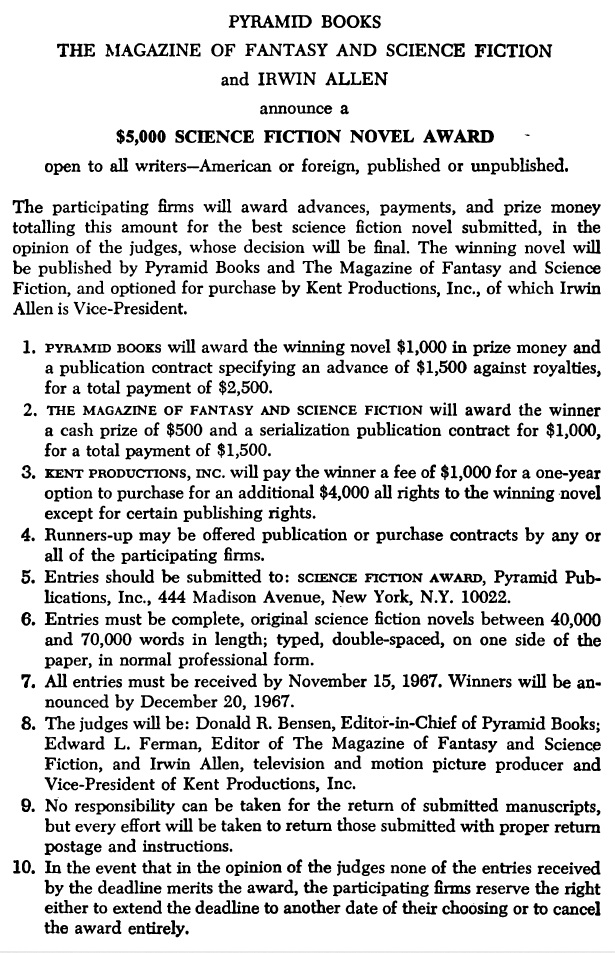

Knowledgeable readers may be able to identify the source. Yes, this really says "medieval China" to me too.

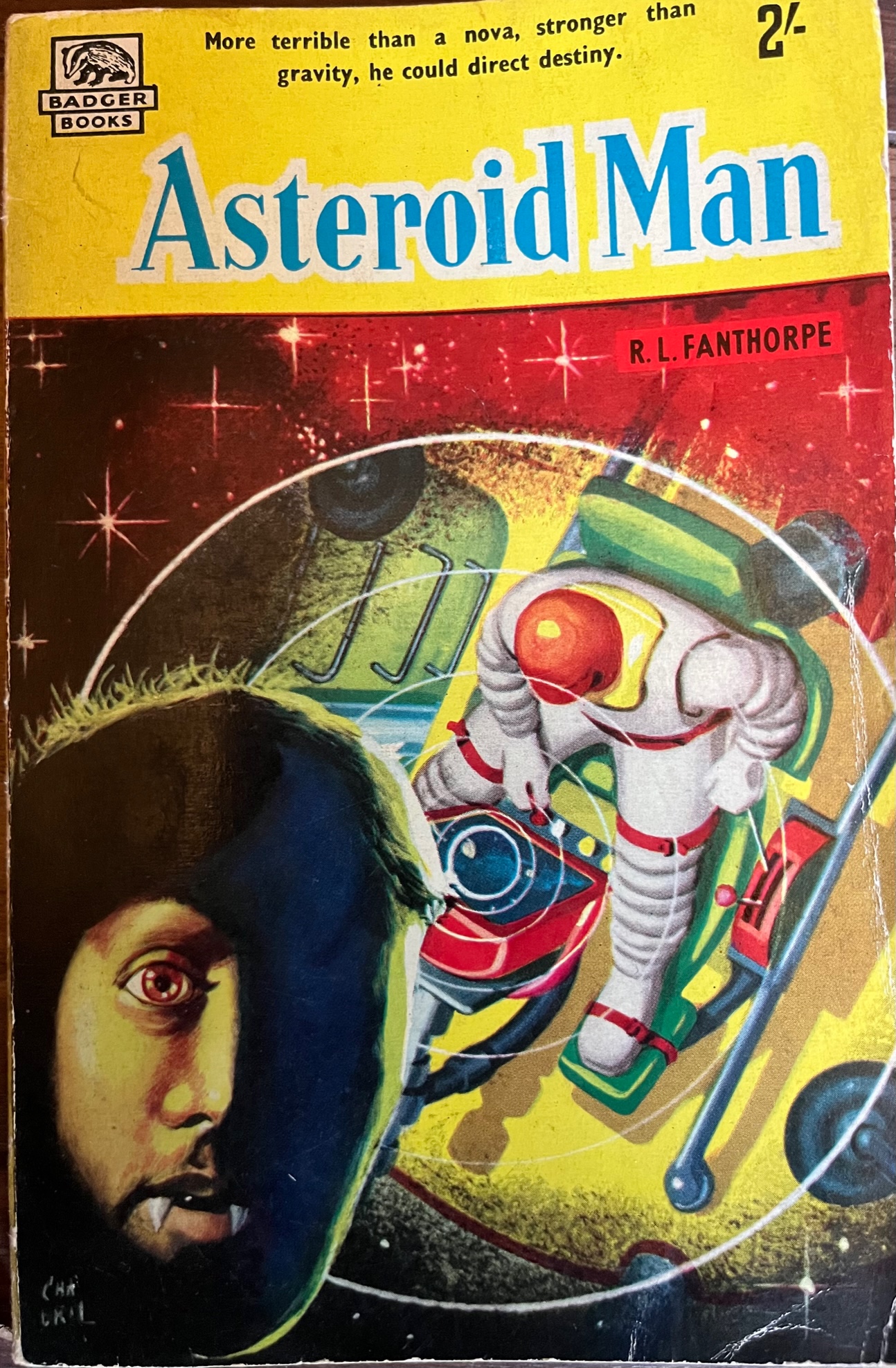

Yes, this really says "medieval China" to me too. Don't expect it to make sense.

Don't expect it to make sense. And yes, Fang Guy really *is* in the story.

And yes, Fang Guy really *is* in the story. He's a fake fakir.

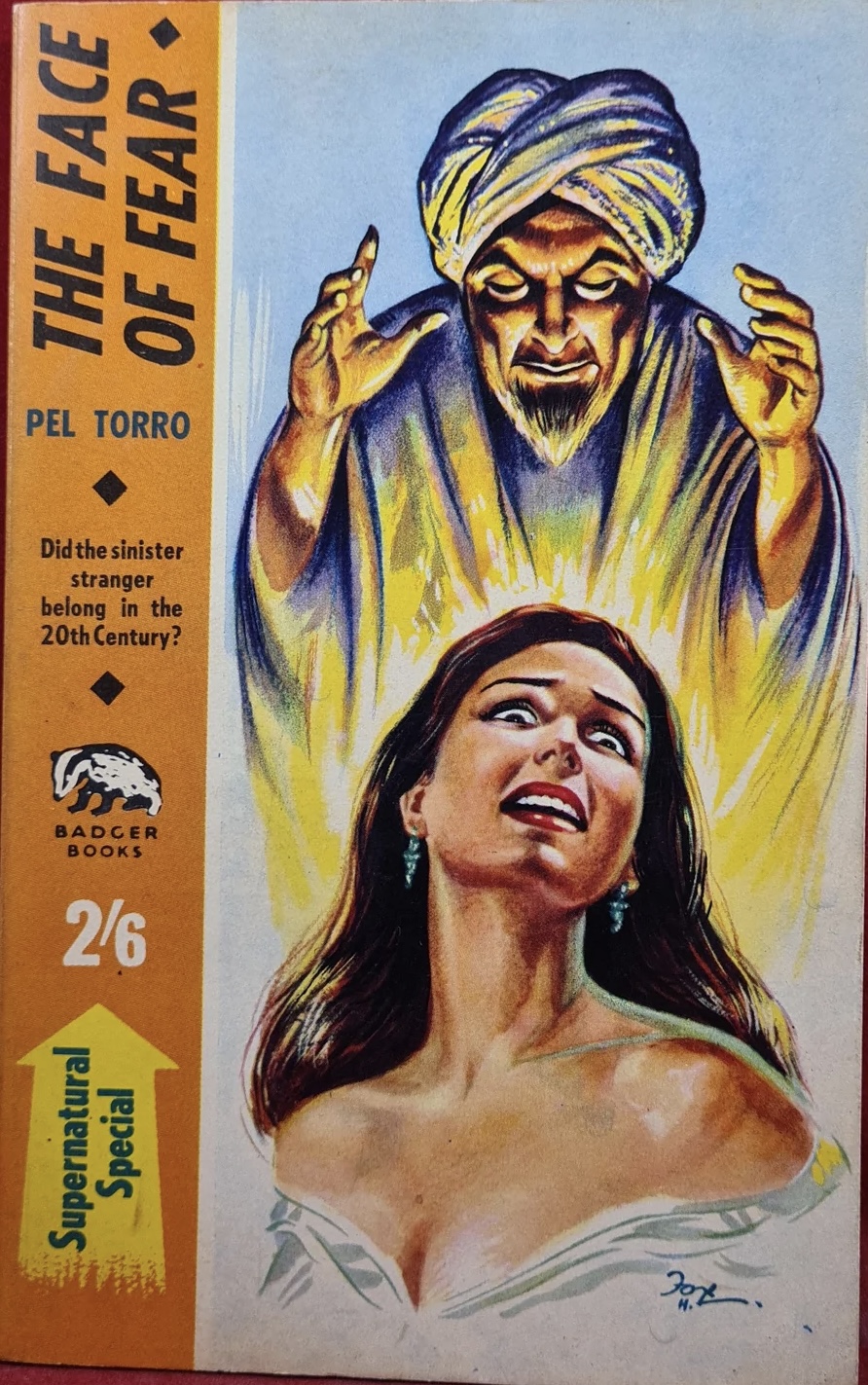

He's a fake fakir. Yes, this really happened.

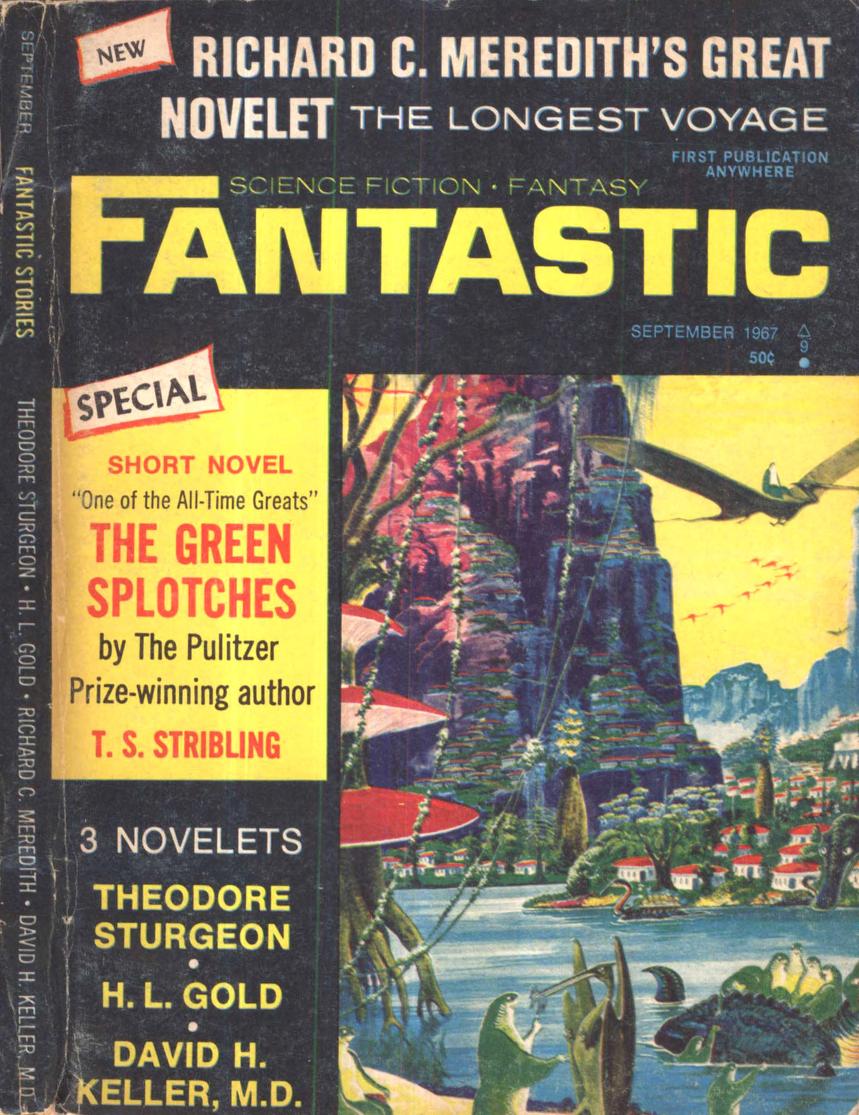

Yes, this really happened.![[August 8, 1967] Distant Signals (September 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Fantastic_v17n01_1967-09_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

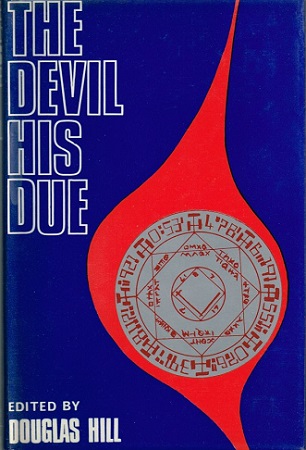

![[August 6, 1967] A Dark Future (<i>The Devil His Due</i> by Douglas Hill)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Devil-His-Due-2-306x372.jpg)

![[August 4, 1967] Bond Movie. James Bond Movie (<i>Casino Royale</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670427casinoroyale-672x372.jpg)

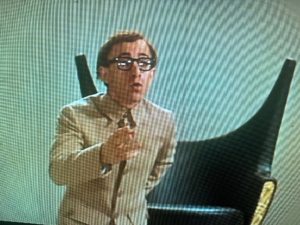

In plot terms, Casino Royale is two almost entirely separate films, tenuously linked by a handful of scenes. The ‘first’ plot features David Niven as a retired, now celibate, British agent named James Bond, who is returned to service when all other agents are being killed off due to their fondness for sex. Bond recruits a new agent, Coop (Terence Cooper), and instigates an anti-sex training programme, thus allowing the movie to have its cake and eat it through sequences of Coop being sexually tempted but boldly resisting. Mata Bond (Bond’s daughter by Mata Hari) is recruited by her father and discovers a plot to auction SMERSH agent Le Chiffre’s collection of blackmail materials to various military forces from across the world, whose senior staff have been photographed in compromising situations.

In plot terms, Casino Royale is two almost entirely separate films, tenuously linked by a handful of scenes. The ‘first’ plot features David Niven as a retired, now celibate, British agent named James Bond, who is returned to service when all other agents are being killed off due to their fondness for sex. Bond recruits a new agent, Coop (Terence Cooper), and instigates an anti-sex training programme, thus allowing the movie to have its cake and eat it through sequences of Coop being sexually tempted but boldly resisting. Mata Bond (Bond’s daughter by Mata Hari) is recruited by her father and discovers a plot to auction SMERSH agent Le Chiffre’s collection of blackmail materials to various military forces from across the world, whose senior staff have been photographed in compromising situations. Meanwhile Mata and Bond travel to Casino Royale, where they discover the mastermind behind SMERSH, Doctor Noah, is in fact Jimmy Bond, Bond’s nephew (Woody Allen), who has become a supervillain through feelings of inadequacy. Noah is tricked into swallowing a pill that turns him into a walking atomic bomb and a free-for-all breaks out in the casino, with invasions by cowboys, Indians, seals, the Keystone Kops, a French legionnaire, and actor George Raft — the whole thing eventually blowing sky-high as the heroes fail to prevent Noah from exploding.

Meanwhile Mata and Bond travel to Casino Royale, where they discover the mastermind behind SMERSH, Doctor Noah, is in fact Jimmy Bond, Bond’s nephew (Woody Allen), who has become a supervillain through feelings of inadequacy. Noah is tricked into swallowing a pill that turns him into a walking atomic bomb and a free-for-all breaks out in the casino, with invasions by cowboys, Indians, seals, the Keystone Kops, a French legionnaire, and actor George Raft — the whole thing eventually blowing sky-high as the heroes fail to prevent Noah from exploding. Certain elements of the story are indeed more or less direct spoofs, either of the James Bond franchise itself or of the wider spy series craze. The film starts with a pre-credits sequence which is just a tiny scene of Bond meeting a French agent in a pissoir, simultaneously setting up and destroying expectations of a James Bond-style pre-credits action sequence. Mata Bond’s trip to Germany places her within a stage set straight out of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, in a nod to the huge debt the spy film genre owes to Expressionist artform. The supporting cast includes people who’ve either appeared in Bond movies or the many independent television spy series that have cashed in on the Bond craze, notably Ursula Andress but also Vladek Sheybal and promising young character actor Burt Kwouk. As in many spy series, doubles and duplicates turn up frequently. The bizarre conceit of having all the agents, male, female, and, by the end of the adventure, animals, named James Bond/007, can be construed as a sly comment on the fact more than one actor has played Bond, or even a metatextual joke about the proliferation of code-names and numbers in such series. And, of course, the villain is motivated by a sense of personal and sexual inadequacy—what spy series villain isn’t?

Certain elements of the story are indeed more or less direct spoofs, either of the James Bond franchise itself or of the wider spy series craze. The film starts with a pre-credits sequence which is just a tiny scene of Bond meeting a French agent in a pissoir, simultaneously setting up and destroying expectations of a James Bond-style pre-credits action sequence. Mata Bond’s trip to Germany places her within a stage set straight out of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, in a nod to the huge debt the spy film genre owes to Expressionist artform. The supporting cast includes people who’ve either appeared in Bond movies or the many independent television spy series that have cashed in on the Bond craze, notably Ursula Andress but also Vladek Sheybal and promising young character actor Burt Kwouk. As in many spy series, doubles and duplicates turn up frequently. The bizarre conceit of having all the agents, male, female, and, by the end of the adventure, animals, named James Bond/007, can be construed as a sly comment on the fact more than one actor has played Bond, or even a metatextual joke about the proliferation of code-names and numbers in such series. And, of course, the villain is motivated by a sense of personal and sexual inadequacy—what spy series villain isn’t? However, both plots reach their highest, as well as their lowest, moments when they embrace the surreal comedy ethos. Arguably this started with The Goon Show, of which Sellers was a key member, before really finding its home with audiences in the Sixties. Current examples of this genre include What’s New, Pussycat?, Round The Horne, the Dadaist stylings of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and At Last the 1948 Show. The trend is gaining strength: reportedly Paul McCartney is also a fan and is keen to adopt fantastical elements into Beatles films. So it’s not surprising, given the involvement of Sellers and Feldman, that Casino Royale would be taken in such a direction.

However, both plots reach their highest, as well as their lowest, moments when they embrace the surreal comedy ethos. Arguably this started with The Goon Show, of which Sellers was a key member, before really finding its home with audiences in the Sixties. Current examples of this genre include What’s New, Pussycat?, Round The Horne, the Dadaist stylings of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and At Last the 1948 Show. The trend is gaining strength: reportedly Paul McCartney is also a fan and is keen to adopt fantastical elements into Beatles films. So it’s not surprising, given the involvement of Sellers and Feldman, that Casino Royale would be taken in such a direction. The picture’s surreal comedy doesn’t always work. For instance, there’s an annoyingly self-indulgent sequence which seems just an excuse for Sellers to dress up as historical characters. Others are better: Niven’s Bond, for instance, lives on an estate guarded by a pride of lions (“I did not come here to be devoured by symbols of monarchy!” protests the Soviet head of espionage), and the idea James Bond and Mata Hari had a relationship is a somehow appropriate melding of the archetypes of the male and female spy. Mata Bond stops the auction of Le Chiffre’s compromising photos by switching the projector to a war film: as if triggered, the British, American, Chinese and Russian representatives instantly all start fighting each other, in a comment on the Cold War worthy of

The picture’s surreal comedy doesn’t always work. For instance, there’s an annoyingly self-indulgent sequence which seems just an excuse for Sellers to dress up as historical characters. Others are better: Niven’s Bond, for instance, lives on an estate guarded by a pride of lions (“I did not come here to be devoured by symbols of monarchy!” protests the Soviet head of espionage), and the idea James Bond and Mata Hari had a relationship is a somehow appropriate melding of the archetypes of the male and female spy. Mata Bond stops the auction of Le Chiffre’s compromising photos by switching the projector to a war film: as if triggered, the British, American, Chinese and Russian representatives instantly all start fighting each other, in a comment on the Cold War worthy of  Furthermore, the surrealist aspect transforms some of the problems and conflicts that arose during its production, from potential flaws to part of an overarching psychedelic atmosphere. Orson Welles had apparently insisted on performing magic tricks on camera, but these become both a send-up of the contrived “eccentricities” of spy-series villains and a deeper comment on illusion and artifice. The title sequence, which starts out as a simple riff on Bond films’ animated credits, becomes increasingly disconcerting, the imagery including walls of eyes staring pitilessly out at the viewer, with connotations of surveillance and voyeurism.

Furthermore, the surrealist aspect transforms some of the problems and conflicts that arose during its production, from potential flaws to part of an overarching psychedelic atmosphere. Orson Welles had apparently insisted on performing magic tricks on camera, but these become both a send-up of the contrived “eccentricities” of spy-series villains and a deeper comment on illusion and artifice. The title sequence, which starts out as a simple riff on Bond films’ animated credits, becomes increasingly disconcerting, the imagery including walls of eyes staring pitilessly out at the viewer, with connotations of surveillance and voyeurism. At the climax, the presence of multiple James Bonds escalates into a scenario where literally everyone becomes the titular hero; and this, together with the recurrence of doubles and duplicates, poses serious questions about how we construct our identity in modern society. At the end, everyone dies, going to Heaven or Hell, the accompanying random images and cheery music underscoring that there can be no guaranteed rescue or happy-ever-after in the atomic age.

At the climax, the presence of multiple James Bonds escalates into a scenario where literally everyone becomes the titular hero; and this, together with the recurrence of doubles and duplicates, poses serious questions about how we construct our identity in modern society. At the end, everyone dies, going to Heaven or Hell, the accompanying random images and cheery music underscoring that there can be no guaranteed rescue or happy-ever-after in the atomic age.![[August 2, 1967] The Bounds of Good Taste (September 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/IF-Cover-1967-09-672x372.jpg)

President de Gaulle with foot firmly in mouth.

President de Gaulle with foot firmly in mouth. This alien dude ranch has become a popular honeymoon spot. Art by Gray Morrow

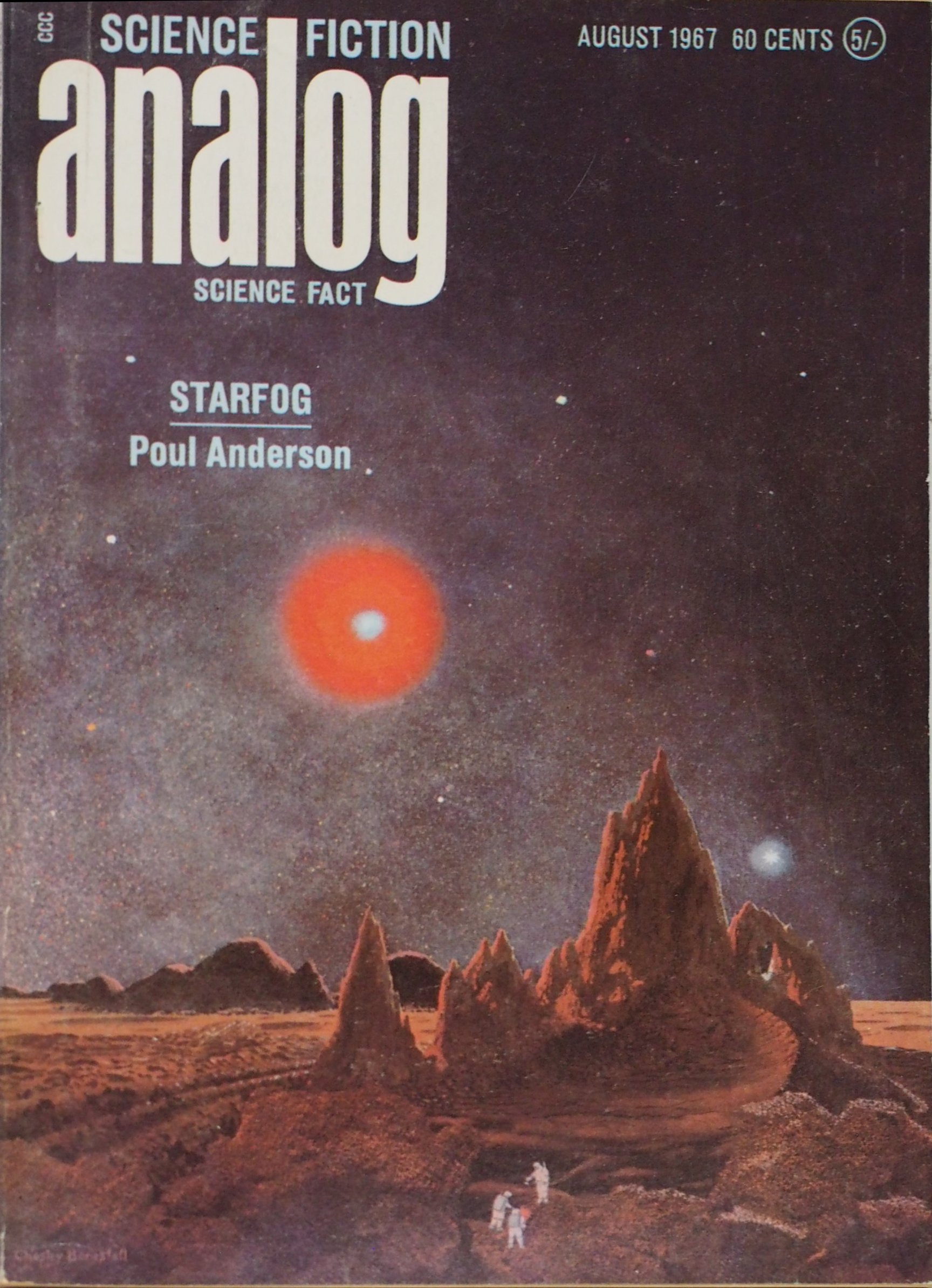

This alien dude ranch has become a popular honeymoon spot. Art by Gray Morrow![[July 31, 1967] Canceling waves (August 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670731cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 28, 1967] The Shock of the New – Rabbits, Hedgehogs and Kazoos (<i>New Worlds</i>, August 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/NW-September-1967-672x372.jpg)

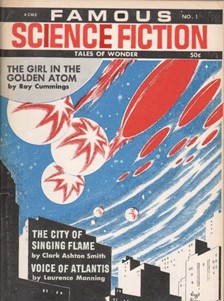

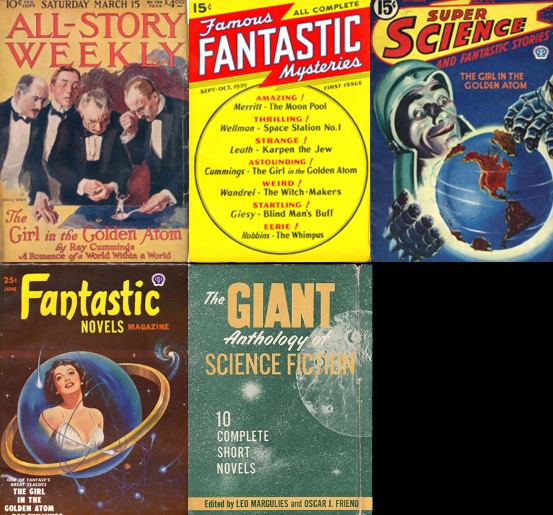

![[July 24, 1967] Not Feelin’ Groovy (<i>Famous Science Fiction</i> #1-3)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Famous-Cover-Image.jpg)

![[July 20, 1967] An Analog of <i>Analog</i> (August 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670720cover-659x372.jpg)