by Victoria Silverwolf

The Boy's Club

It's hardly shocking news to point out that much of modern American society is dominated by men. To pick a random example, out of one hundred members of the United States Senate, there is only one woman.

Margaret Chase Smith (Republican, Maine) who also served in the House of Representatives from 1940 to 1948, when she was elected to the Senate.

Popular culture isn't much different. Take, for example, a new television series that's drawing a lot of attention. It's named for the two male hosts.

From left to right, straight man Dan Rowan and goofy partner Dick Martin.

I have to admit that I'm already a big fan of Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In, which premiered last month. Besides the rapid-fire pace of its jokes, I also admire the talents of a quartet of regular female performers on the program. Here's to you, Ruth Buzzi, Jo Anne Worley, Judy Carne, and new cast member Goldie Hawn!

This is not meant to detract in any way from the fine work provided by the men on the series. Bravo, Henry Gibson, Arte Johnson, and announcer Gary Owens!

(I would be remiss if I did not also mention the appearance of a remarkable entertainer calling himself Tiny Tim on the premiere episode. His performance is unique, to say the least.)

Dick Martin is nonplussed.

The same pattern of male domination is often found in the world of popular music (though not always–if the Beatles are the Kings of Pop, the Supremes are the Queens.) Right now, for instance, the Number One hit in the USA is Green Tambourine, a sprightly little psychedelic number performed by some guys calling themselves the Lemon Pipers.

Even the 45 rpm single is groovy-looking.

Proving the old adage that behind every great man there's a great woman, the lyrics for the song were written by Rochelle (Shelley) Pinz.

Pinz with Paul Leka, who wrote the music.

Stag Party

As we'll see, the only original work of fiction in the latest issue of Fantastic takes male domination to an extreme, in a certain way. Let's take a look.

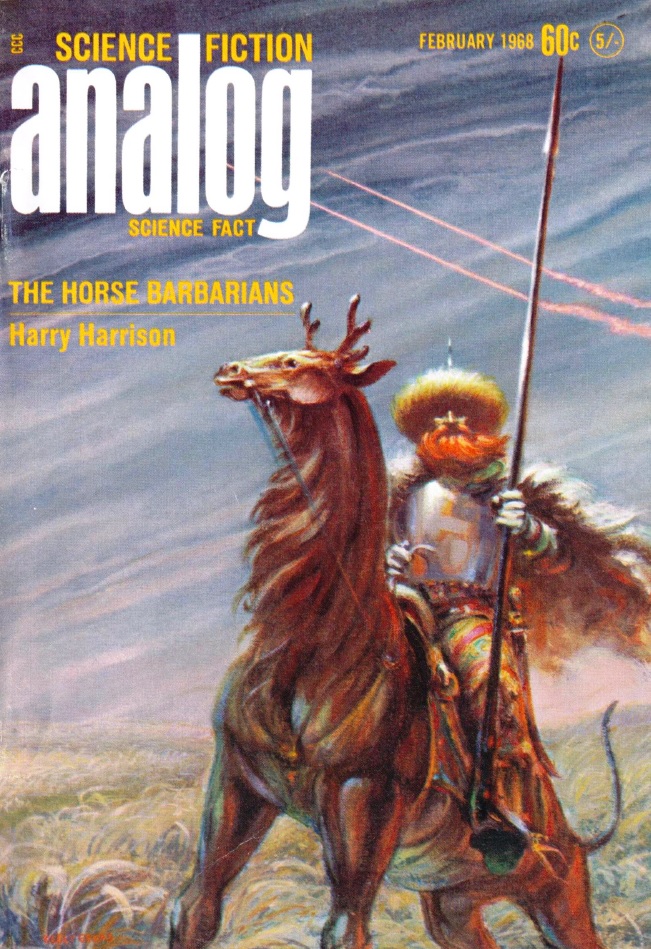

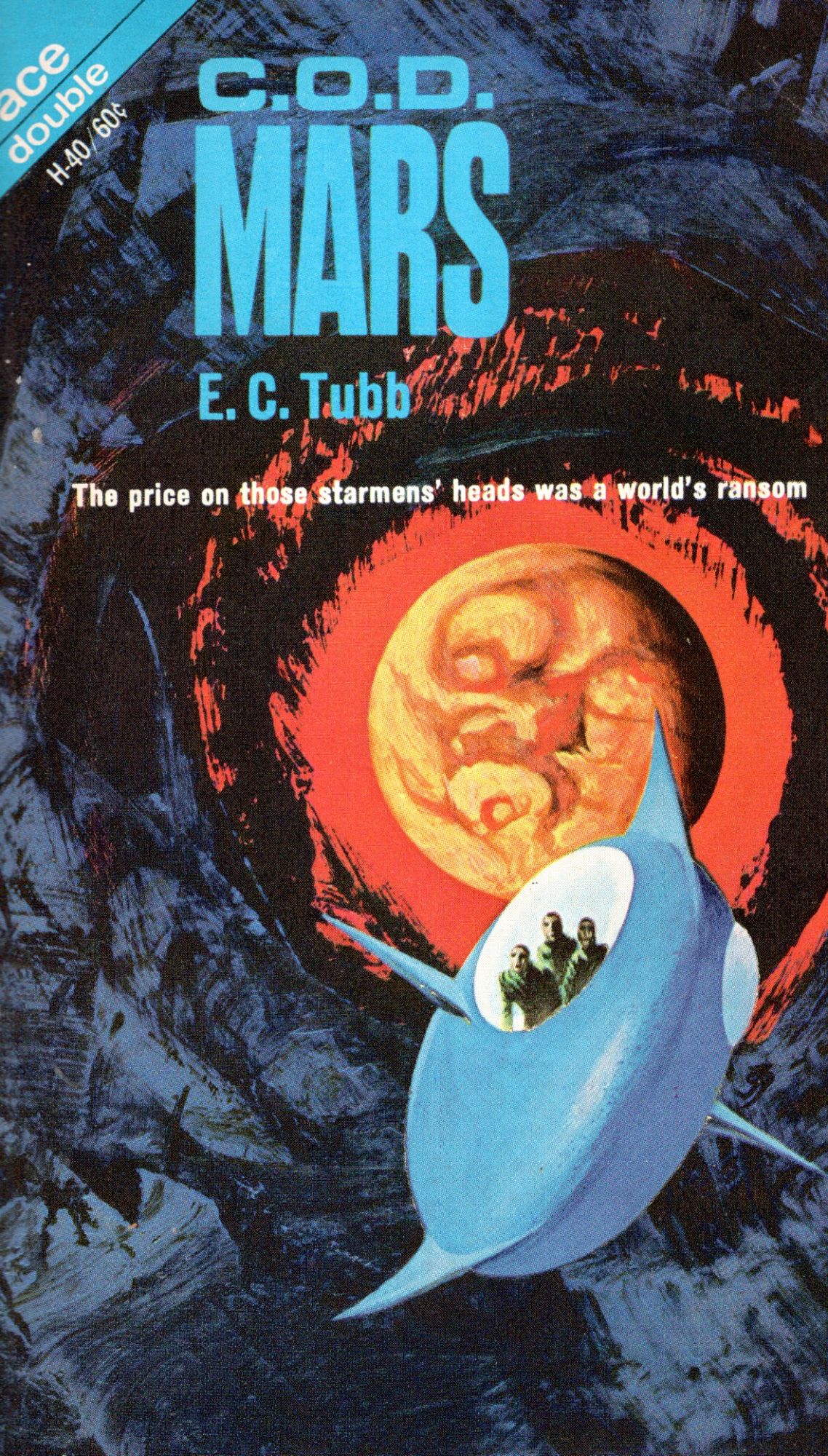

Cover art by Johnny Bruck.

As usual, the cover comes from another source. In this case, it's from an issue of the popular German publication Perry Rhodan.

The original looks better, even if I can't read it.

Spartan Planet (Part One of Two), by A. Bertram Chandler

Illustrations by Jeff Jones.

As the title implies, the setting is a world with a culture based on ancient Greece, particularly Sparta. Society is rigidly divided into various classes, determined at birth. The main character is a military policeman.

The native animals on this planet reproduce by splitting themselves apart, a bloody and painful process. The human inhabitants believe that they used to have children this way, but now make use of a so-called Birth Machine, which makes things much easier. Nobody has access to this fabled device, except for members of the Doctor class.

Did I mention that there are no women to be seen? This is an all-male world, at least as far as the vast majority of the population knows.

There's an implication of homosexual relationships. The so-called helots tend to be slightly effeminate, compared to the red-blooded Spartans, and there's mention of close friendships between members of the two classes.

The planet receives twice-yearly shipments from their only colony world, founded by a group of rebels. The two societies have a distant relationship, trading goods but having no other contact.

The story begins when a starship from another group shows up. Aboard is our old friend John Grimes, who has appeared in a handful of other stories by Chandler. More important is the fact that he's got an ethologist with him, here to study the planet's culture.

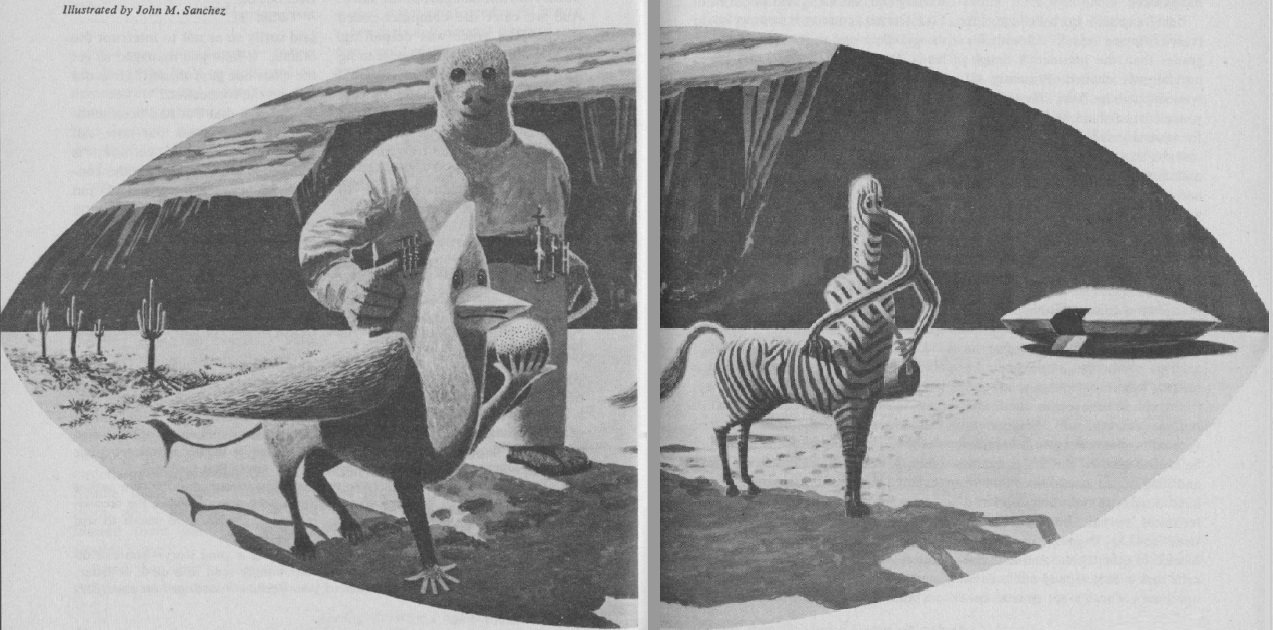

The ethologist. Can you tell there will be trouble?

The locals, having never seen a woman before, assume the ethologist is either deformed or an alien. The protagonist feels a peculiar mixture of emotions. (The implication is that males are inherently attracted to females, even if they have no idea that such people exist. That's debatable, at least.)

Meanwhile, a security officer gives the policeman a secret assignment. It seems that the Doctors have some kind of hidden agenda. The hero sneaks into a forbidden area and gets a hint the world doesn't quite work the way he thought it did.

Chandler tips his hand pretty early, so it's probably not giving away too much to reveal that there are, indeed, women on the planet. The Doctors keep them locked away in a sort of harem.

I don't know how the rest of this is going to resolve itself, or what role Grimes will play, but so far it's fairly interesting. As I've noted, there isn't much suspense about the Doctors' conspiracy, but I'll keep reading.

Three stars.

The Court of Kublai Khan, by David V. Reed

The March 1948 issue of Fantastic Adventures supplies this mystical swashbuckler.

Cover art by Robert Gibson Jones.

A fellow is obsessed by Samuel Taylor Coleridge's famous incomplete poem Kubla Khan (note the change in spelling from the title of the story.) So much so, in fact, that he finds himself back in time, in the palace of that fabled ruler. (Let's ignore the fact that the poem has nothing to do with real history.) People from all ages who are passionate about something wind up there. (There's even a prehistoric man around.)

Illustrations by Robert Fuqua.

Coleridge himself is present, because of his love for the maiden he saw in his vision of Xanadu. Our hero tries to help him win the adored lady. If I managed to follow the confusing plot correctly, the same day keeps repeating itself over and over, ending in Coleridge's failure. The protagonist does his best to change this endless cycle.

Sometimes this means using a sword against man or beast.

Part of his motivation is that he wants Coleridge to finish the poem. Complicating matters is a rival for the woman's affection. There's also the peculiar fact that once somebody achieves his passionate desire, he goes back to his own time with no memory of what happened.

The premise is intriguing, but I found the story difficult to follow. I never quite understood how this magical form of time travel was supposed to operate.

The bulk of the text consists of a letter the hero writes to his buddy, chronicling his adventures. (Somehow he manages to remember things just long enough to jot them down.) There's plenty of action, but the ending is anticlimactic.

I was disappointed that I never got to see Where Alph, the sacred river, ran/Through caverns measureless to man/Down to a sunless sea.

Two stars.

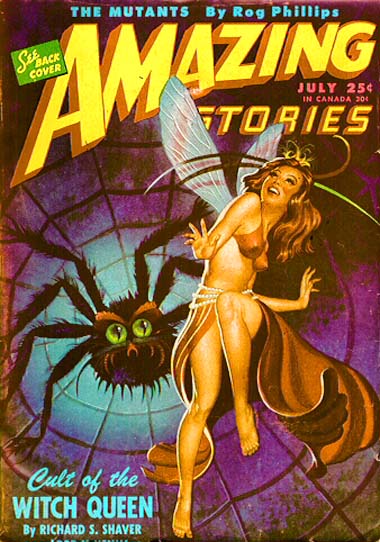

Heart of Light, by Gardner F. Fox

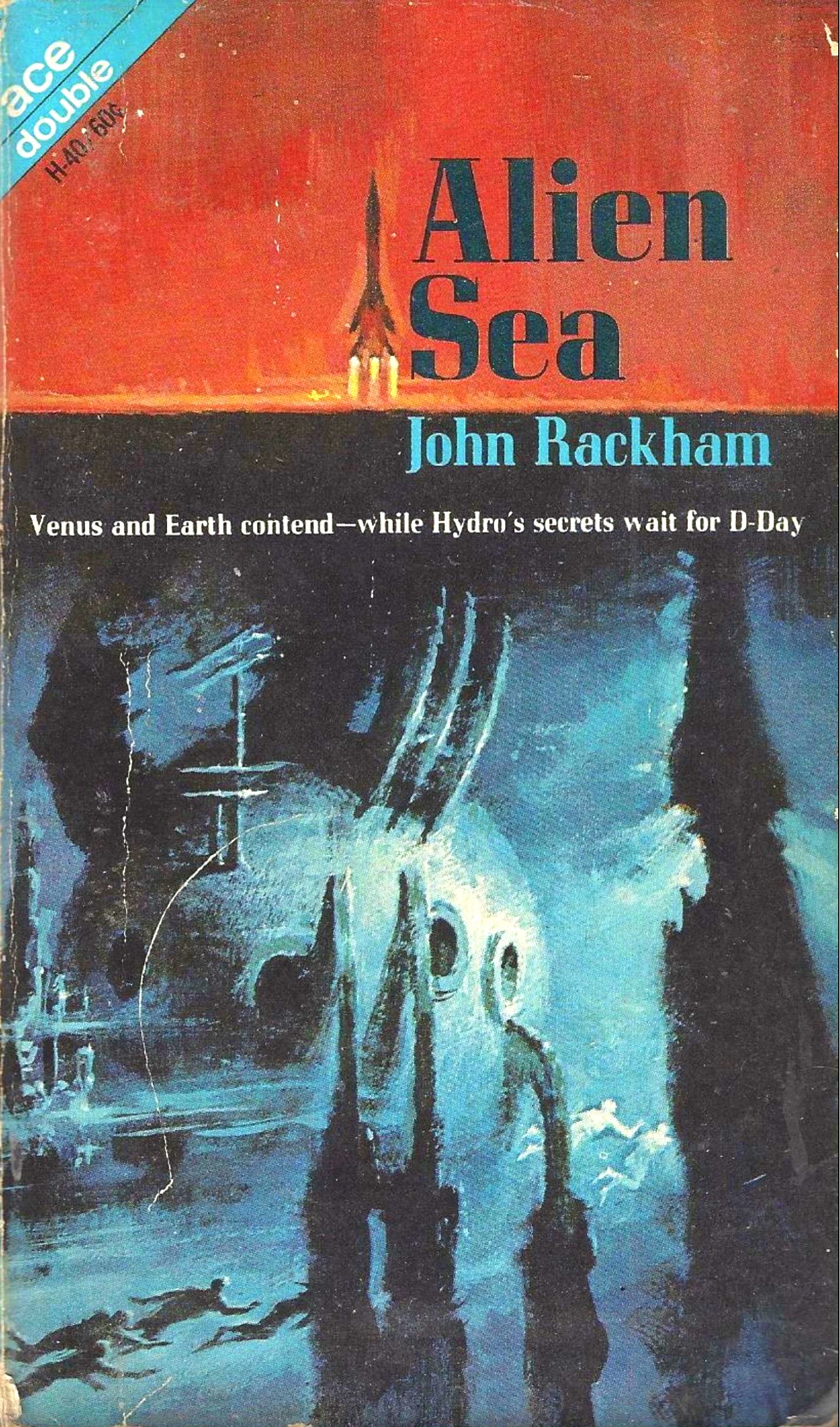

The July 1946 issue of Amazing Stories is the source of this weird tale.

Cover art by Walter Parke.

An archeologist finds an incredibly ancient bronze statue in the Australian desert. He hears a voice coming from inside, and breaks open the very thin outer shell. Inside is a figure made entirely of diamond.

(There's some nonsense about carbon being the source of life. Thus, a diamond being can live. Yeah, sure.)

Anyway, the diamond person turns into a beautiful woman. (At first, the hero assumes the figure is that of a man. I guess the voice and shape weren't enough of a clue.) She takes the fellow on a bizarre journey through time. (At least, I think so. This was another story that confused me.)

Illustration by Julian S. Krupa.

She leads him to an entity made of light. He finds out that a civilization from another planet, led to Earth by the benevolent light being, fought off loathsome creatures straight out of a Lovecraft yarn. (The story even mentions H. P. Lovecraft and his acolyte August Derleth by name.) All the people died, except for the woman, who was preserved by the power of the light entity. Now it's time to wipe out the enemy for good.

The author throws a bunch of stuff at the reader at a breakneck pace. The whole thing doesn't make a lot of sense, but it's not boring.

Two stars.

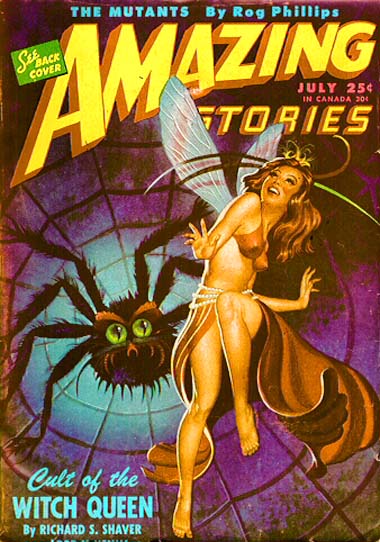

The Great Steel Panic, by Fletcher Pratt and Irvin Lester

We go way back to the September 1928 issue of Amazing Stories for this disaster story.

Cover art by Frank R. Paul.

Somebody, or something, cuts through the cables of the Brooklyn Bridge. The same thing happens to elevators, subways, and other modern devices made of iron and steel.

Illustration also by Paul.

A brilliant scientist figures out what's going on, and what should be done about it.

That's the entire plot. Even the disaster stuff, which kills lots of people, is described dispassionately, in a second-hand fashion. The result is a very uninvolving piece. David H. Keller's similar work, The Metal Doom, wasn't that good, but at least it developed the basic idea to a greater extent.

The nifty Scientifiction symbol on the cover of the old magazine is a lot more impressive.

Two stars.

Incompatible, by Rog Phillips

This science fiction horror story first appeared in the September 1949 issue of Fantastic Adventures.

Cover art by Robert Gibson Jones.

An alien spaceship crashes on Earth. The creature inside lives on the blood of living organisms. (Shades of Queen of Blood!)

She's also telepathic, and uses this ability in an attempt to survive in this very strange world. Besides that, she can change her appearance, eventually looking like a very attractive woman.

Illustration by W. E. Tilly.

Things work out pretty well for her, until a military man gets a little too friendly.

In essence, this is a vampire story. The first part, told from the point of view of the alien, is quite effective. The author does a fine job describing Earth and humans from an extraterrestrial's perspective. The rest of the story goes downhill here from there. Some of the sections told from the human point of view are extraneous.

Two stars.

Fantasy Books, by Fritz Leiber

The first installment of this new book review column discusses the nonfiction tome Spirits, Stars and Spells: The Profits and Perils of Magic by L. Sprague de Camp and Catherine C. de Camp. Leiber gives a glowing review to this skeptical account of human superstitions. I mention this mostly to contrast it with Harry Harrison's editorial, which talks about the same article about dowsing rods used by the United States Marine Corps as appeared in the latest issue of Analog. Buy the de Camps' book instead.

No rating.

I Love Lucifer, by William P. McGivern

Finishing up the magazine is this tale from the December/January 1953/1954 issue of Amazing Stories.

Cover art by Mel Hunter.

A little girl who claims her name is Lucifer shows up at a place where a man watches over a junkyard of old spaceships. The only other resident is a boy the same age as the girl. The two kids play together among the worn-out vessels.

Illustrations by Ernest Schroeder.

A government agent shows up at the place, looking for escaped criminals. Meanwhile, the kids meet a seemingly friendly man who wants their help in getting away from bad guys. Let's just say that there are plots and counterplots, and neither the man nor the girl are quite what they claim to be.

Would you name this child Lucifer?

The title may suggest something supernatural, but nothing of the kind occurs. I imagine the author called the girl Lucifer just so he could pun on the name of a popular TV show of the time. (Get it?)

The story caught my interest at first, but quickly lost me. The plot started to reek of space pirates and other corny stuff. The true nature of Lucifer was just silly.

Two stars.

In Need of a Woman's Touch

Maybe my increasing awareness of feminism (they're starting to call it Women's Liberation these days, since the National Organization for Women was created last year) just puts me in a cranky mood, but it seems that this all-male issue wasn't very good. One so-so half of a novel and a bunch of unsatisfactory old stories don't add up to much. A few female writers (and fewer reprints) may not be the whole answer, but it sure wouldn't hurt. Meanwhile, go read a good book.

At least the title is honest about the contents.

You could also catch up on the news and see if they cover the emerging women's movement.

![[February 18, 1968] Yet(i) Again, London Is Under Attack (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Web Of Fear [Part One])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680218underground-672x372.jpg)

![[February 16, 1968] In their words (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Return to Tomorrow")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680216title-672x372.jpg)

![[February 14, 1968] Triple John (February 1968 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680214titles-672x372.jpg)

![[February 12, 1968] The Power of Cinema (<i>The Power</i>, a movie)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680212poster-672x372.jpg)

An image I'm not going to remove from my brain easily

An image I'm not going to remove from my brain easily Can *you* spot the bad guy?

Can *you* spot the bad guy? On the other hand, handsome people do get their kit off a lot.

On the other hand, handsome people do get their kit off a lot. George Hamilton about to have an encounter with a dipping bird.

George Hamilton about to have an encounter with a dipping bird. Mrs Van Zant is Japanese, and why shouldn't she be?

Mrs Van Zant is Japanese, and why shouldn't she be?![[February 10, 1968] It's a Man's World (March 1968 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/cover-2-672x372.jpg)

![[February 8, 1968] The Trek Offensive (<i>Star Trek</i>: "A Private Little War")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680208title-672x372.jpg)

![[February 6, 1968] The Most Dangerous Dame (<i>Confessions of a Psycho Cat</i>) and From the Land of Hype (Ellison's <i>From the Land of fear</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680206covers-672x372.jpg)

![[February 4, 1968] More of the Same (March 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/IF-1968-03-Cover-434x372.jpg)

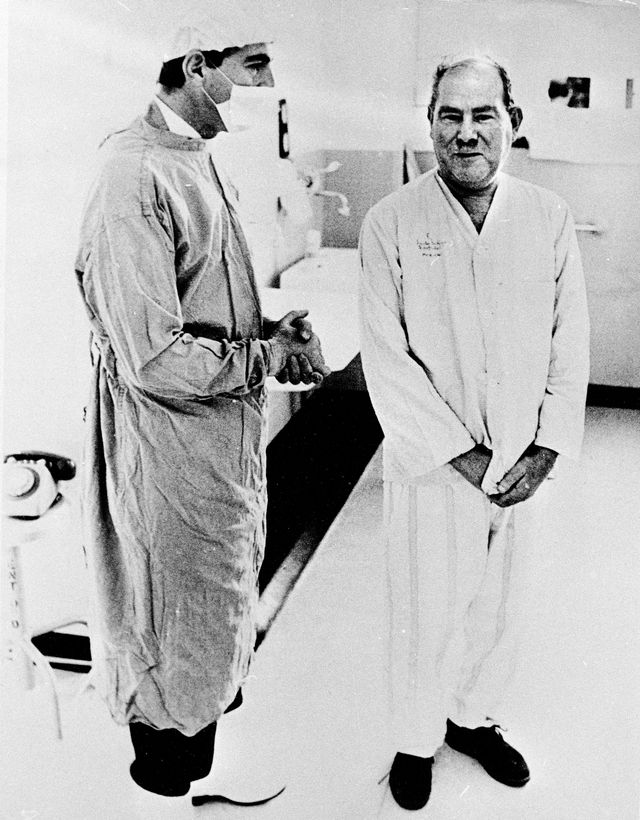

Dr. Barnard (I.) and Philip Blaiberg (r.), probably before the surgery.

Dr. Barnard (I.) and Philip Blaiberg (r.), probably before the surgery. Dr. Shumway at a press conference last fall (l.), Mike Kasperak and his wife, Ferne (r.)

Dr. Shumway at a press conference last fall (l.), Mike Kasperak and his wife, Ferne (r.) This unpleasing collage is for Harlan’s new story. Art by Wenzel

This unpleasing collage is for Harlan’s new story. Art by Wenzel![[Feb. 2, 1968] All creatures great and small (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Immunity Syndrome")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680202title-672x372.jpg)

![[January 31, 1968] Too much and too little (February 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680131cover-651x372.jpg)