by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

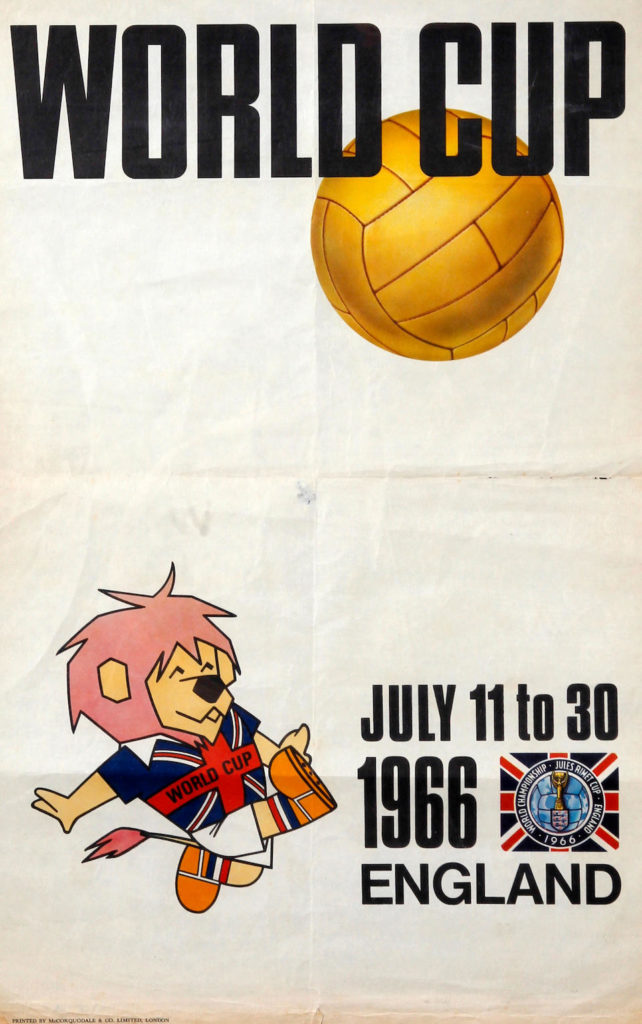

After my brief mention at the end of last month about England and the soccer World Cup, I had better start by congratulating them on their tournament win since last time we spoke. The country does seem to have got behind them – indeed, there’s been little else talked about here since they won. Whilst I’m not a fan of football (soccer to you!) particularly, I must curmudgeonly admit that the mood of the country has been rather pleasant.

In this spirit of optimism and change, there’s also been some interesting changes with the British magazines. At the moment I’m not sure whether these changes have been made for good reasons or bad, but they might just stir life into the magazines that have rather been treading water on the whole over the last few months.

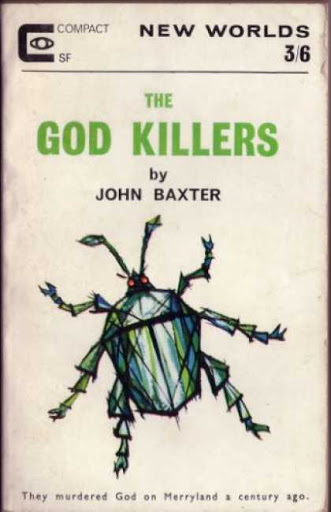

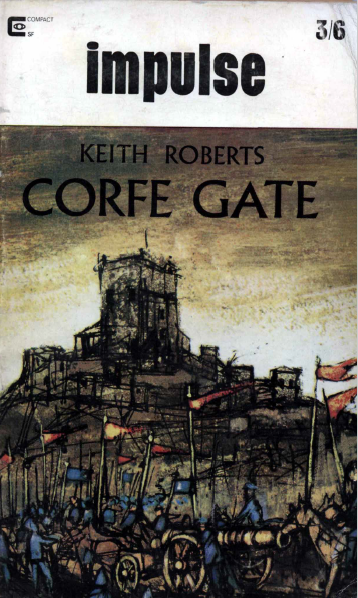

Cover by Keith Roberts – again!

Or rather SF Impulse. Notice the subtle change? The magazine seems to be trying to attract the interest of traditional readers by nailing its genre roots firmly to the mast. Interestingly, I understood that this was something the editor Kyril Bonfiglioli was keen not to do when the magazine changed its name to Impulse.

In fact, where is Kyril? The magazine has no Editorial at all this month, instead going with a “Critique” by Harry Harrison instead. This was mentioned in last month’s issue, although I was rather expecting Kyril to be about as well. Has he been deposed? Perhaps after his complaints about not knowing what an Editor does in the last few issues this leaves Kyril with more time to – you know – edit.

Let’s move on. To this month’s actual stories.

Make Room! Make Room! (Part 1 of 3), by Harry Harrison

When this was mentioned as coming up, I was very pleased. The magazine was going to have to do something big to cap Keith Roberts’ Pavane series for me, and this was clearly it.

Mind you, I have been less impressed with Harrison’s last two serialised novels, Plague From Space and Bill, the Galactic Hero (shudder.) But this one sounded great.

Whereas this is just the first part for us in Britain, being in the USA fellow Galactic Journey-er Jason Sacks has had the chance to read the whole novel, lucky thing. His wonderful review goes into much more depth and detail than I would here. So I will point out his review, with thanks, and say that so far I agree with everything he has said.

This is the best Harrison I’ve read in ages, if not one of the best stories in Impulse to date. Admittedly, its scenes of shabbiness and squalor are rather depressing, but its description of a world of overcrowded excess, crime and a lack of resources is done with imagination and flair. The situation is entirely possible and the characters appropriate for that setting. I hope the quality continues. I was so impressed, I’m awarding it 5 out of 5 – my first, I believe.

Wolves by Rob Sproat

After such a great start it would be difficult to maintain such a standard, and so we go from the great to the typical “Bonfiglioli filler”, had Kyril been here. This is the third story we’ve had in the magazines from Rob, none of which have particularly impressed me, sadly. And so it is again here. A story of creatures that have haunted Mankind for millennia and yet are rarely seen. When their presence is noted by a drunken man, he is killed. Lots of talk here about Ancient Ones that doesn’t seem to mean much. A weak horror story that is bleak and yet strangely predictable. 3 out of 5.

The First, Last Martyr by Peter Tate

Another relatively new author, who seems to be liked by many readers. His last story was The Gloom Pattern, in the June 1966 issue of New Worlds. This one is a tale of Hubert Flagg, a window dresser whose occupation makes him part of the pop-culture and yet inwardly he hates it. As an act of rebellion against current trends and to become a celebrity, Flagg attempts to kill people at a concert by the current pop favourite The Saddlebums, which I guess is not just a comment on society but also a bit of a dig at bands like The Beatles. On a good day this could have been a satire in the same vein as Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius, but instead it just seems odd, and not in a particularly good way. 3 out of 5.

Disengagement, by T. F. Thompson

Another surreal ramble through the viewpoints of various characters. Think of it like an inferior Frankenstein story from multiple perspectives, a similar re-tread of clichés that seems all too similar to Robert Cheetham’s The Failure of Andrew Messiter in last month’s New Worlds. (Are new ideas really that hard to come by?)

It seems more like a Hammer Horror film than the “really chilly horror” the banner attempts to persuade me it is. Although actually I like Hammer Horror movies… this less so. Some of the characterisation is awful. Any story that has a character named “Doctor Dog” and tries to make a joke out of it deserves not to be taken seriously. Marks for effort, not originality. 2 out of 5.

A Comment by E. C. Tubb

E C Tubb returns with an opinion piece on the state of science fiction, rather akin to Harrison’s Critique at the beginning of the issue. Here Tubb takes on the thorny issue of sex in science-fiction, pointing out that it has been around longer than sf and it is wrong for the New Wave to “dwell on it”. To quote, “The more sex you put in a story the less action, characterisation, futuristic background, scientific content and plain, old, entertainment value you leave out.”

Whilst I understand the author’s point of view, it does read a little like one of the oldsters complaining about the new kids on the block.

The Scarlet Lady by Alistair Bevan

Lastly, back to the stories. Here we have the return of Alistair, a regular author but who is also author/editor/artist Keith Roberts. Both names have appeared regularly in these magazines.

Here Alistair continues an ongoing theme of motor car stories. His last was a rather excitable story of future traffic congestion, road rage and restrictive laws in the story Pace That Kills back in the May 1966 issue of Impulse. By contrast, this is a tale that attempts to emulate Weird Tales in its story of a possessed car and its effect on two brothers and their respective families. No reason is given for the automobile’s actions, which show a constant drain on the owner’s monetary funds and a taste for blood. Whilst it is – please pardon the expression – as cliched as hell, I must admit that I quite enjoyed it for all of its silliness. Some of the passages reminded me in style and tone of Roberts’ version of contemporary lifestyle as read in The Furies in July – September 1965. It is too long, but was a fun read. Much better than the last story, for all of its limitations. 3 out of 5.

Summing up Impulse

And that’s it for SF Impulse this month. At over 80 pages most of the magazine is taken up with Harrison’s novel, which is its selling point. As a result, I liked the issue a lot, even when the rest of the material suffers by comparison. I was surprised by how much I enjoyed the Bevan story, even if it is repeating old cliches.

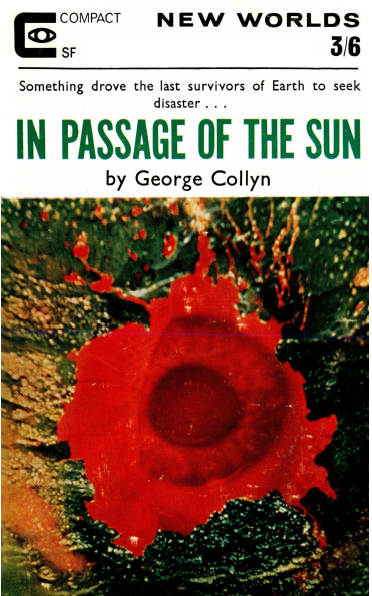

And with this, onto issue 165 of New Worlds, hoping that it is also better this month.

The Second Issue At Hand

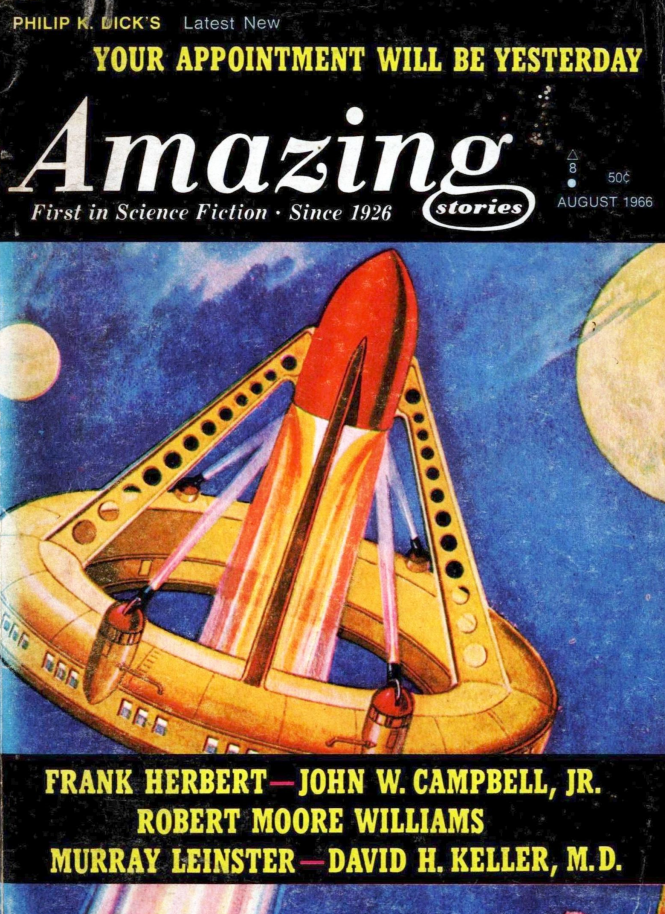

Cover by Keith Roberts – him again!

Like last month’s New Worlds the Editorial is not by editor Moorcock, but a film review by a guest reviewer. Last month, La Jetee was praised by J. G. Ballard as something extraordinary.

This month, Alphaville directed by Jean-Luc Godard has a rather different response. Guest reviewer John Brunner begins his review with “Let’s get one thing straight to begin with. Alphaville is a disgracefully bad film, reflecting no credit to anybody – especially not on those critics who have puffed it as a major artistic achievement.” Well, that should certainly grab the reader’s attention!

To be fair, Brunner makes some good points, although the review really reminds me that all reviews are little but opinions and in this world the New Wave will gain as much criticism as praise. Our own Kris Vyas-Myall reviewed Alphaville, for example, and had a very different response. Interestingly, Brunner does add that La Jetee, reviewed by Ballard last month and seen by Brunner as a double-bill, completely overshadows Alphaville.

Brunner’s writing is entertaining, though, and as a deliberately provocative read is a much more interesting read than any of the other Editorials of late.

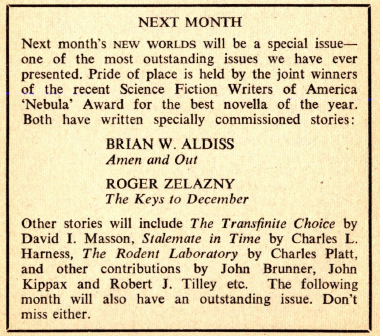

To the stories!

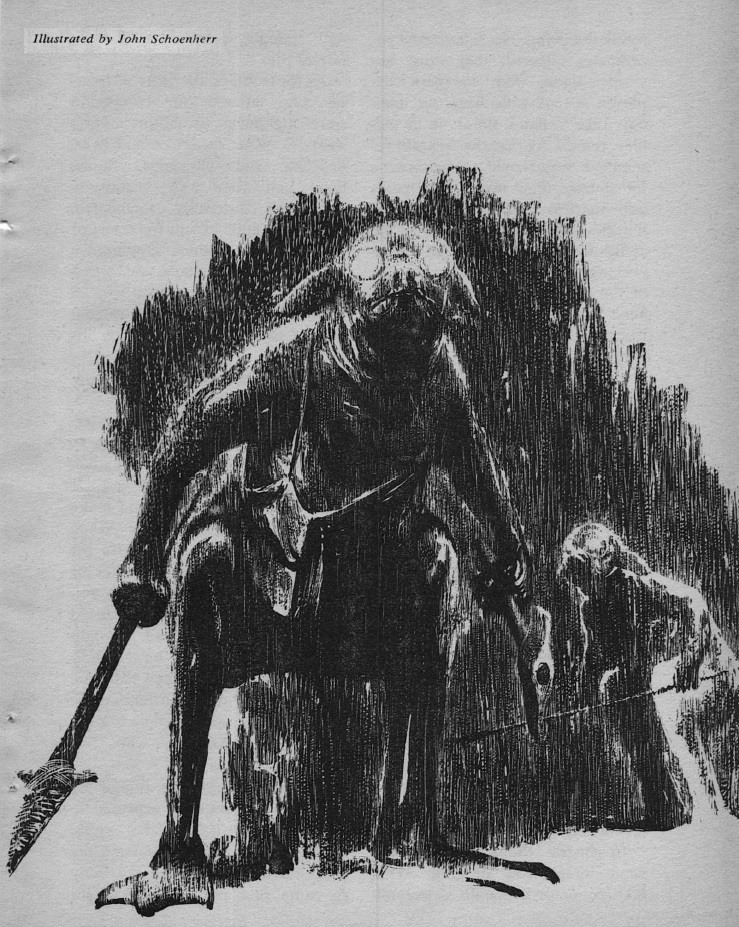

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Amen and Out, by Brian Aldiss

Another appearance from Harry Harrison’s friend Brian Aldiss, who was also here last month. (Again: has anyone ever seen the two of them in one room together?) The cover describes this story as ”Irreverent, thought-provoking stuff that only Aldiss can do well”, which I agree with, although I would further qualify by pointing out that such irreverence can also lead to wildly uneven material from Mr. Aldiss.

(Where has “Dr. Peristyle” gone to, by the way? Just a thought.)

The good news is that this one is not quite as madcap as it could have been. Amen and Out is a story of a future where a number of characters with different backgrounds are at the Immortality Investigation Project – one is a supervisor of the immortals, one a young assistant, one an acid head itinerant and the other a doorman. They each communicate with their Gods, and are all consequently given instructions with various consequences for themselves and the Immortals held in the Project. The twist in the story is that the Gods are actually an AI. It’s good fun, and feels like Aldiss wrote it with a permanent grin on his face, though will no doubt offend anyone seriously beholden to a religion. A 4 out of 5.

The Rodent Laboratory, by Charles Platt

Charles Platt’s been a regular here for a while. This is a story of rats in a laboratory being observed as a group social experiment, and what can happen when the rats develop new behaviour and the scientific community watching them are put under stress. It gains points from me for being a ‘proper’ science-experiment-based story with a touch of the laboratory experiment pulp stories of the 1930s, although the ending is almost something out of Weird Tales. Overall, it reads well enough but feels like minor-league stuff, nothing we’ve not read before. 3 out of 5.

With a lack of artwork this month we have instead this quote, which seems to have inspired the story.

Stalemate in Time, by Charles L. Harness

I’ve mentioned in the past of Charles being a veteran author who seems to be trying to embrace the New Wave of writing. If sales of his novel The Rose are anything to go by, this has been popular, if met with varying degrees of success.

Here we have a reprint. The story was first published as Stalemate in Space back in 1949. Now renamed, it does feel like an old-style piece of pulp fiction. This is clearly intentional – the story begins with a purple-prosed quote from Planet Stories which seems to sum it up nicely. I’m not quite sure what Mike is trying to do here. Is this one of those examples to show that ‘the old stuff’ is still worth reading, as he did with Harness’s Time Trap back in the May 1965 issue? Or is it just filler? Whatever the reason, Stalemate in Space is an engaging if dated Space Opera story, which makes up with enthusiasm what it lacks in logic – but I wish the magazines would stop trying to sneak reprints to bulk out their issues. 3 out of 5.

Look On His Face, by John Kippax

William Kibbee is a Christian priest on a mission to the planet of Kristos V. Unsubtle, heavy-handed religious allegory. 2 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

The Transfinite Choice, by David Masson

The return of recent genre superstar David Masson whose sudden and dramatic appearance in these magazines has been stellar, although with slightly diminishing returns. Here is the story of Naverson Builth, who finds himself transported from 1972 to the year 2346. Lots of difficulties with language, which seems to be a Masson specialty, before we discover that Naverson finds himself working for a world government known as Direct Parameter Control. There are some interesting concepts put forward to Builth in this future, and some in turn suggested by Bulith, before the story crashes to a halt with a poor ending that we’ve come across before. Masson’s writing is still readable and still involves ambitiously big ideas, but I rather feel David has passed his peak. A slightly disappointing 3 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

The Keys to December by Roger Zelazny

I have repeatedly said that I think that Roger is one of the best American writers of recent years to have taken on the New Wave of science fiction and run with it. He keeps producing quality stories which are thoughtful, readable and also genuinely original. His last story here, For A Breath I Tarry, has been rightly nominated in this year’s Hugo Awards. So any return to these Brit magazines is something to be pleased about, I think.

And this is another cracker. The key premise is that in this future people can be adapted pre-birth in order to cope with the environment they will live on. It is different to the usual Zelazny fare, beingless philosophical and surprisingly hard-science-based, something that I could see Poul Anderson or Hal Clement writing.

To this Roger sets up a situation that Jarry Dark, a homeless Coldworld catform, his betrothed Sanza and his friends in the December Club who have put up the money, move to a planet where they will terraform the planet into something they can use. Whilst reconnoitring the planet they observe a species that they call Redform that even though thousands of years will pass to allow for adaptation will be unable to adapt in the face of their impending catastrophic event.

Knowing that the intelligent species will die but at the same time being unable to do anything about it sets up the sort of dilemma that challenges both the reader and the characters, and at the end gave me an emotional reaction akin to Tom Godwin’s The Cold Equations.

Surprisingly different for Zelazny, both elegaic and emotional, I can see this one being nominated for future awards. A high 4 out of 5.

Letters and Book Reviews

We begin this month with Bill Barclay giving a potted biography of writer and anthologist Sam Moskowitz and then reviewing Moskowitz’s latest book of biographical essays. It does sound interesting.

James Colvin (aka Mike Moorcock) then covers a broad range of material. A highlight this month is Colvin being rather unsurprisingly unimpressed with Asimov’s novelisation of the movie Fantastic Voyage. The subtitle for this review, Per Ardua Ad Arteries did make me laugh, as well as the clinical evisceration of the novel.

The shorter reviews, all written by initialled reviewers, include story collection The Saliva Tree by a certain Brian W Aldiss, many of which have appeared in these magazines, Judith Merril’s 10th edition of The Year’s Best SF and the 15th volume of The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction. All are liked – Zelazny comes out particularly well – though these three books show me the divide in style and content opening up between the old style stories and the so-called New Wave. Things are still changing….

Lastly there is a great review for Edgar Pangborn’s A Mirror for Observers, which ”stands head and shoulders above most sf”.

Very pleased to see the return of Letters pages this month. Generally detailed and thought-provoking, though generally still raking over the same themes of "What is SF?" and "What is this new SF?"

Summing up New Worlds

A stellar line up, with many of Moorcock’s favourite writers here. Whilst I could quibble and say that some of these stories from writers with a proven track record are not the author’s best, there are many that are very good. Aldiss is good but, unsurprisingly, Zelazny’s story is better. It’s not quite perfect (Kippax, I’m thinking of your story), but there’s a great deal of range and a good deal of quality. One of the best issues of New Worlds for a long time.

Summing up overall

A tough choice this month. Harrison’s novel is the best thing I’ve read here and dominates Impulse, quite rightly, although most of the rest are unmemorable. By contrast, the stories in New Worlds are not quite as good, but the range of the quality is greater. Zelazny’s story in New Worlds is as good as Harrison’s and this is the best New Worlds I’ve read for a few issues.

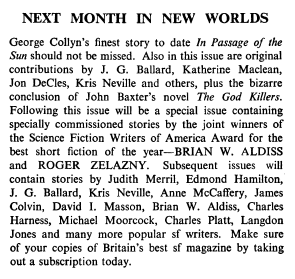

So – very pleased to say that both magazines have (thank goodness!) improved enormously this month. Whilst Harrison’s serial novel seriously impresses in the new SF Impulse, the range and breath of quality makes New Worlds the best this month. Let’s hope this continues. Must admit, the next New Worlds sounds good…

Until the next…

![[July 28, 1966] Cat People and Overpopulation (<i>SF Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, August 1966)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Impulse-NW-Aug-66-672x372.jpg)

![[July 22, 1966] Ridiculous! (August 1966 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/amz-0866-cover-665x372.png)

![[July 20, 1966] An Endless Summer (August 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/660720cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 8, 1966] South Pohl (August 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/660708cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1966] The Big Thud (August 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/IF-1966-08-Cover-644x372.jpg)

![[June 30, 1966] Not Reading You (July 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/660630analog-500x372.jpg)

![[June 28, 1966] Scapegoats, Revolution and Summer <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, July 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Impulse-NW-July-1966-672x372.png)

![[June 2, 1966] Bad Decisions (July 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/IF-1966-07-Cover-654x372.jpg)

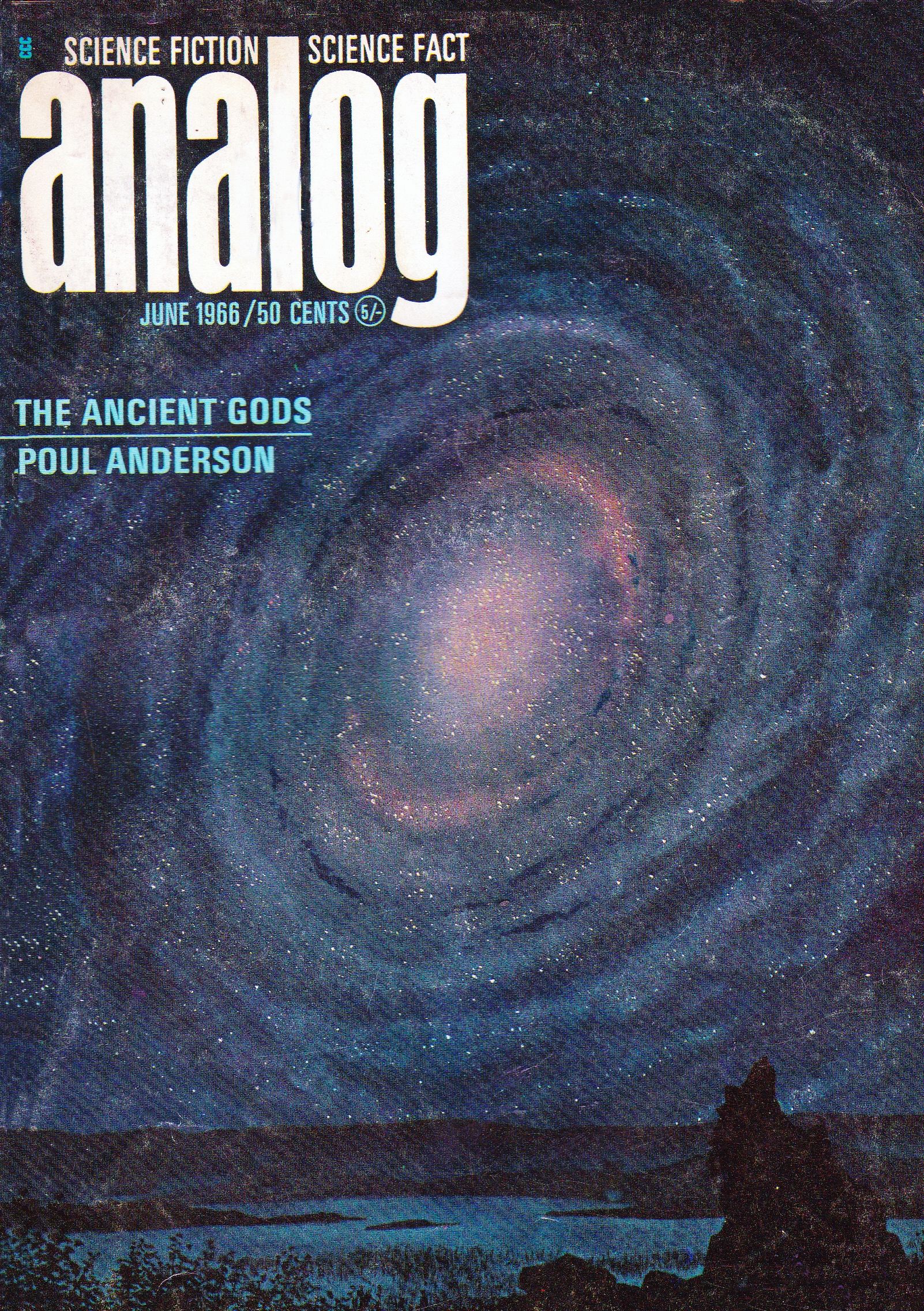

![[May 31, 1966] Worth Remembering (June 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/660531cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 24, 1966] Hatchetmen, Marilyn Monroe and God Killers (<i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, June 1966)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Impulse-New-Worlds-June-1966-672x372.jpg)