by John Boston

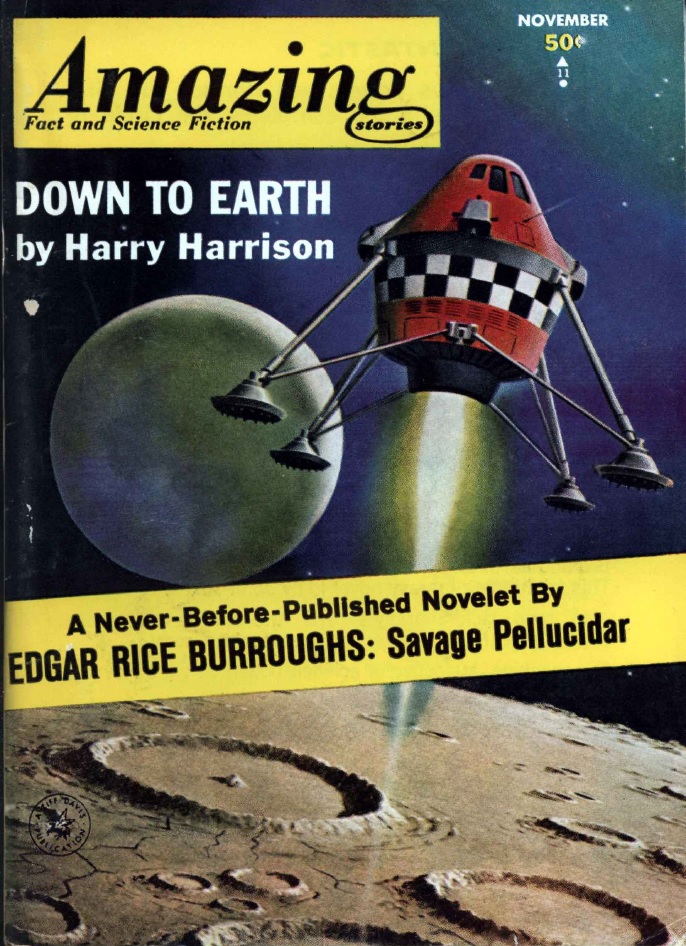

Amazing is starting to resemble a good cop/bad cop routine, and this December 1963 issue is brought to us by the good cop.

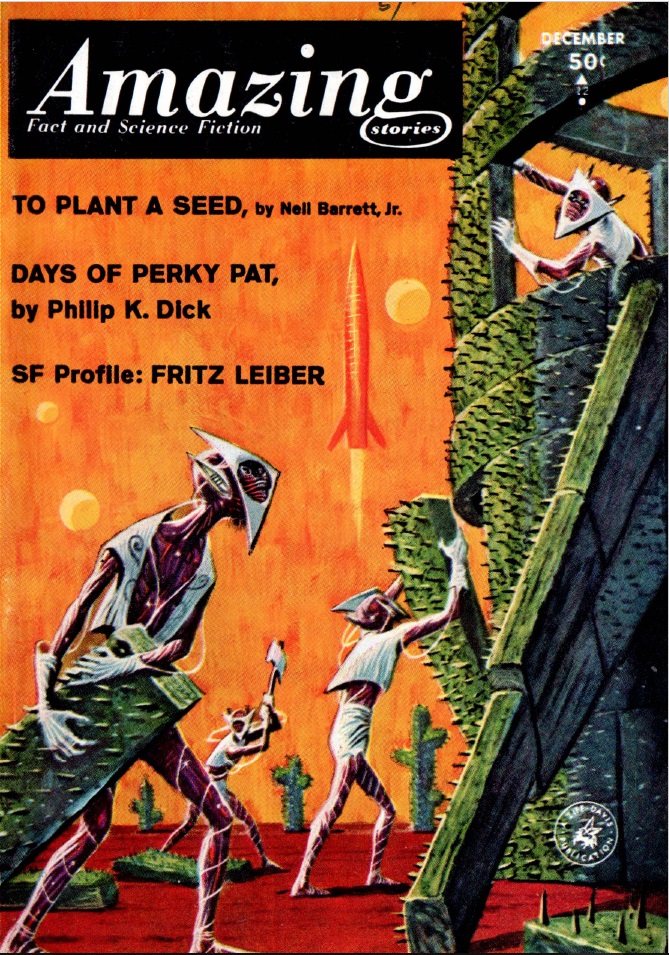

The cover story is To Plant a Seed, a longish novelet by Neal Barrett, Jr., in which this still fairly new writer earnestly wrestles with one of the more familiar plots in SF’s cupboard: Earthfolks go starfaring, encounter colorful primitive aliens, usually highly religious; observe them under a strict rule of noninterference; then the aliens start doing really strange stuff. After the mystery is milked for a while, the revelation: typically, the aliens aren’t so primitive after all, or at least they are the remnants of something greater.

Here the aliens are the barely humanoid Kahrii, who cultivate the Shari, plants which are the only other life form here on the extremely hot and otherwise barren Sahara III (and how likely is that ecology?). The Shari provide their food, clothing, and everything else they have. So why have they suddenly cut down their entire crop and begun using the pieces to build something in this desert that looks like a boat, which they could never have seen? And should the human observers break the command against interfering to stop this racial suicide? Barrett wrings a decent amount of suspense out of these questions; one knows generally what is going to happen, but why and how remain interesting enough.

As for the human observers: these are Gito, the assigned observer (male of course), and Arilee, whose job title is Mistress, the latest of several in Gito’s career. But she’s pretty smart for a Mistress—a Nine, in fact, on some completely unexplained social ranking scale—and Gito has allowed her to wander around the tunnels of the Kahrii and make her own observations. Despite her formal designation as a male plaything, she is a significant actor in the story, and she ultimately saves Gito’s bacon. And in fact that’s part of Barrett’s point, that she transcends the condescending role she occupies. But it’s still frustrating and annoying to see a reasonably capable SF writer displaying more imagination in devising a completely alien society than in thinking about the likely future of his own. Aside from that, this is a pretty solid performance on a well-established theme. Three stars, towards the top of the range.

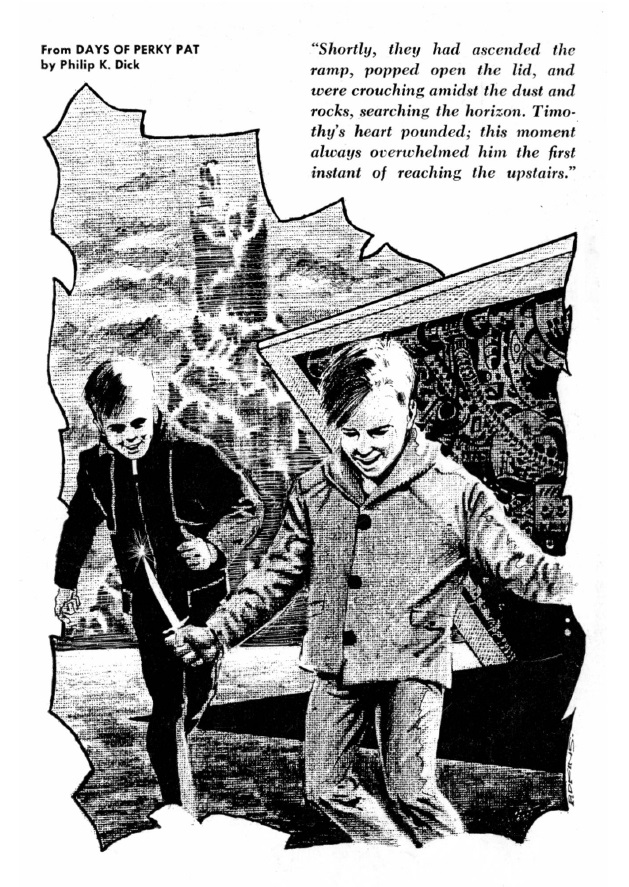

The other novelet is The Days of Perky Pat by Philip K. Dick, who has now had stories in three consecutive issues. This one is far better than the others, which I described as resembling rambling stand-up routines. Here he reverts to his long-standing preoccupation with life after catastrophe, in this case, as in many others, a nuclear war. The characters, called “flukers” because it’s only by a fluke that they survived, live underground in the old fallout shelters, kept alive by the grace of the “careboys,” mollusk-like Martians who drop food and other goods to sustain the flukers’ lives.

The adult humans are completely preoccupied with Perky Pat, a blonde plastic doll that comes with various accessories including boyfriend, which the flukers have supplemented with various improvised objects in their “layouts,” which seem to be sort of like a Monopoly board and sort of like a particularly elaborate model train setup. On these layouts, they obsessively play a competitive game, running Perky Pat and her boyfriend through the routines of life before the war, while their kids run around unsupervised on the dust- and rock-covered surface chasing down mutant animals with knives.

Obviously the author has had an encounter with a Barbie doll complete with accessories, and didn’t much care for it. This is as grotesque a black comedy as you’ll find, with plot developments reminiscent of Robert Sheckley, but not at all played for yocks. Some years ago Anthony Boucher reviewed one of Dick’s books and used the phrase “the chilling symbolism of absolute nightmare.” Here it’s mixed with over-the-top satire and is still pretty chilling. Four stars.

F.A. Javor’s Killjoy is a rather short story on another familiar theme: Earthfolk starfaring to find exotic alien fauna and hunt and kill it, with a twist that will probably be morally satisfying to many. But the whole thing is hyper-contrived. Two stars.

The oddest item in the issue is The God on the 36th Floor by Herbert D. Kastle, who has had a scattered handful of stories in the SF magazines (many more in other genres), but also edited the last two issues of Startling Stories, for what that may be worth. His main credentials, though, are contemporary novels, mostly original paperbacks, with titles like One Thing On My Mind and Bachelor Summer. So it’s not surprising that this story doesn’t read much like what you’d find in an SF magazine; it’s more like something adapted from a script for The Twilight Zone or The Outer Limits.

Protagonist Der (a nickname) works in Public Relations in a big company, but he’s had some sort of breakdown and can’t actually function any more. Through happenstance he’s managed to stay on, collecting his salary and pretending to do a nonexistent job. But a new man, Tzadi, shows up and seems to know a lot about him, and everybody else too.

Further interaction with the mysterious Tzadi suggests that Der is at even more risk than he feared; and things keep moving until we are in the territory of such paranoia epics as Heinlein’s They and Dick’s Time Out of Joint. So it’s another familiar idea, but nicely developed through dialogue and visualization, not to mention unobtrusively slick writing. Three stars, again near the top of the range.

The issue’s biggest surprise is H.B. Fyfe’s The Klygha, which features more spacefaring Earth explorers (I refuse to say Terrans like the author; nobody but SF writers will ever use that word), lobster-like inhabitants of the planet they are exploring, another spacefaring explorer from somewhere else entirely (the Klygha), a cat, lots of telepathy, and some hidden motives.

I am not saying more because the author has juggled these absolutely stock elements from the back pages of the last decade’s SF magazines into an extremely clever construction, and much of the pleasure of it initially is just figuring out what’s going on, in a way a little reminiscent of Bester’s Fondly Fahrenheit. It’s not quite on that level, but it’s certainly a little tour de force, much better than the other Fyfe stories I’ve read, mostly in Astounding and Analog, which are clever enough but entirely too gimmicky and superficial. Four stars.

Sam Moskowitz is back with another “SF Profile,” Fritz Leiber: Destiny x 3, one of his better efforts: he doesn’t say anything overtly wrong or ridiculous, there are no gross offenses against the English language that cannot be attributed to Amazing’s proofreading, and (unlike his usual practice) he gives as much attention to Leiber’s recent work as to that of the ‘30s and ‘40s. Indeed he goes so far as to describe Leiber’s latest novel, called The Wanderer, which has not even been published yet. The title refers to the fact that Leiber has had two significant hiatuses in SF writing and thus has started his career three times, and also to an early novella titled Destiny Times Three, which deserves neither its present obscurity nor Moskowitz’s over-praise. While Moskowitz skips over some of Leiber’s more significant work, that probably has as much to do with space limitations as his preference. Three stars.

And just to put a cap on it, I read The Spectroscope, the book review column by S.E. Cotts, who generally gets little respect . . . and it’s not bad! These are fairly perceptive reviews despite Cotts’ slightly stuffy manner. No stars, since we don’t ordinarily comment on these things at all, but another pleasant surprise.

So: this is certainly the best issue of Amazing this year; in fact, you have to go back to March and April 1962 to find anything comparable. But the bad cop, as always, lurks outside the interrogation room, slapping his blackjack into his palm. Next month, we are promised more Edgar Rice Burroughs.

![[November 13, 1963] Good Cop (the December 1963 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631113cover-669x372.jpg)

![[November 9, 1963] Change and Constancy (December 1963 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/blog631109cover-400x372.jpg)

![[November 5, 1963] Beginning to see the light (November 1963 <i>Gamma</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631105cover-660x372.jpg)

![[November 1, 1963] Bitter taste (November 1963 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631101cover-451x372.jpg)

![[October 28, 1963] … Beatles, Spies and Spacecraft (<i>New Worlds, November 1963</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631028cover-667x372.jpg)

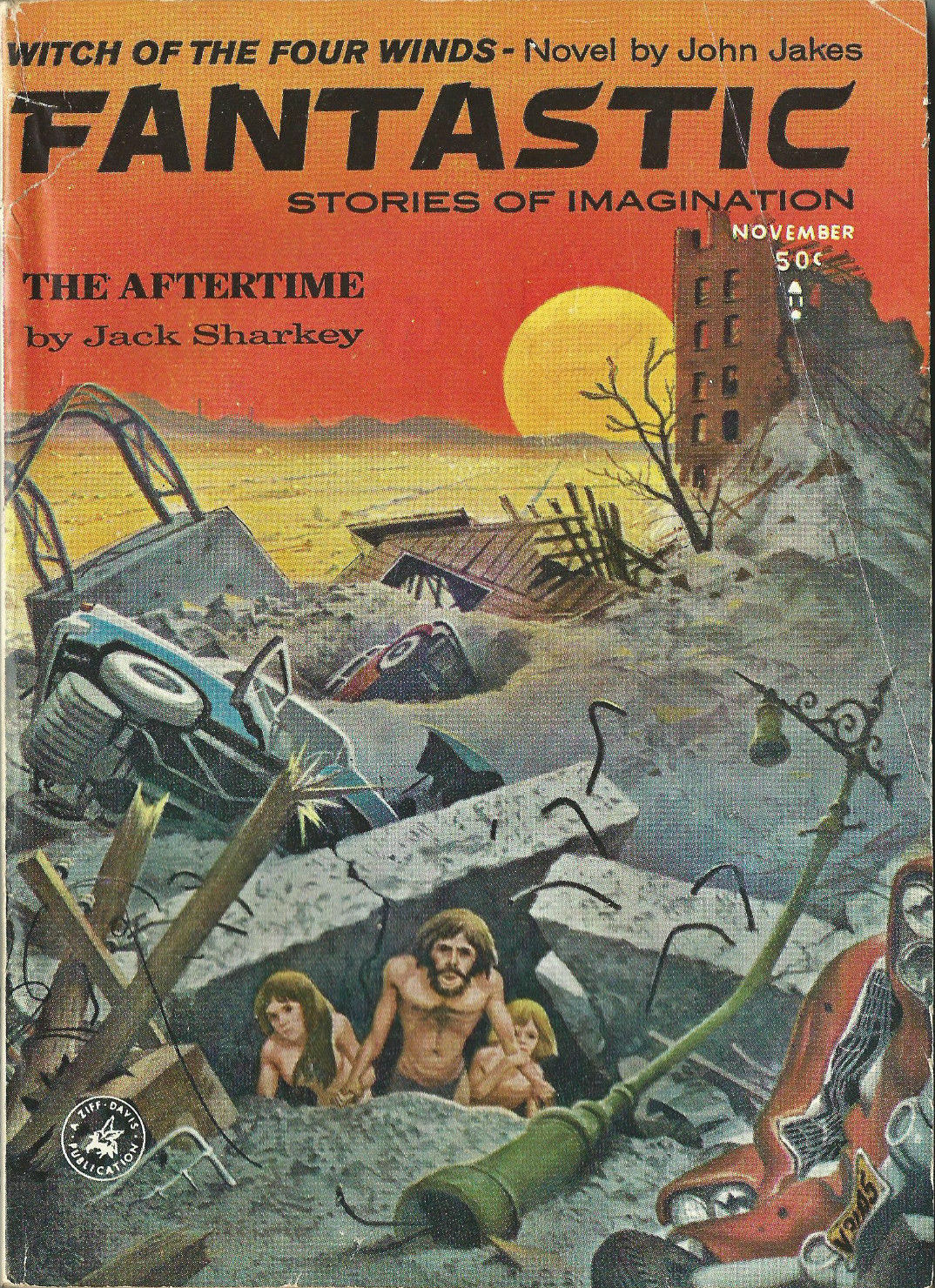

![[October 24, 1963] Sounds Familiar (November 1963 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631024cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 20, 1963] Science Experiments (November 1963 <i>F&SF</i> and a space update)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631020cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 18, 1963] Points of View (December 1963 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631018cover-485x372.jpg)

![[October 12, 1963] WHIPLASH (the November 1963 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631012cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 8, 1963] The Big Lemon (November 1963 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631008cover-474x372.jpg)