by Arturo Serrano

I've spent the last few months exchanging letters with an American friend, who has been educating me about a curious phenomenon they're seeing over there: the quick emergence of new religions whose foundation is, uniformly, some account of an alleged extraterrestrial encounter. From the peculiar case of the Mormon faith, I already knew that the Americans had a unique ability to cook up a doctrine from whole cloth and make it explosively successful in terms of gaining devotees and social influence. But even that knowledge did not prepare me for the alarming piece of investigative journalism which my friend has mailed me along with his latest letter. It's a book published this year, written by a Dane called George Malko, with the title Scientology: The Now Religion. It describes the author's journey to explore and unravel a whole intricate system of theology, liturgy, morality, and salvation begun only two decades ago, by the obviously troubled science fiction writer of moderate fame, named Lafayette Ronald Hubbard.

In a nutshell, Scientology (a bland, uncreative name if I've ever heard one) teaches that the human spirit has lived countless lives in countless bodies on countless planets, and we all carry the scars of emotional trauma accumulated over aeons of reincarnations. But fear not! The same church that reveals to you that you have this problem happens to be selling the solution: by letting a complete stranger take note of your darkest secrets in front of a lie detector, you can achieve the next level of enlightenment. And the next. And the next. With each milestone, you're supposed to become more in control of yourself, more unperturbed by the psychic echo of your past lives, and more capable of performing feats of paranormal wonder. There's a finely subdivided series of degrees of perfection you can rise to, provided that you can afford the requisite study materials. That's the only penitence that this church expects of you: the thousands upon thousands of dollars that it costs to buy its ever-increasing but, unsurprisingly, never complete form of happiness.

![[July 22, 1970] Solace for Your Trillion-Year-Old Spirit (George Malko's <i>Scientology: The Now Religion</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Scientology-672x372.png)

![[July 19, 1970] Dips in road (<i>Maze of Death</i>, <i>The Eternal Champion</i>…and others—July Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700719covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 18, 1970] Two-star three step (July 1970 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700718covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 16, 1970] Journey Behind the Iron Curtain, Journey into Space](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/otherother-672x372.jpg)

![[June 27, 1970] Deeper than Amber, more mindless than a Worm… (June Galactoscope: The Third)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700627covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 17, 1970] Time and Again (June Galactoscope Part Two!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/frolix-672x372.jpg)

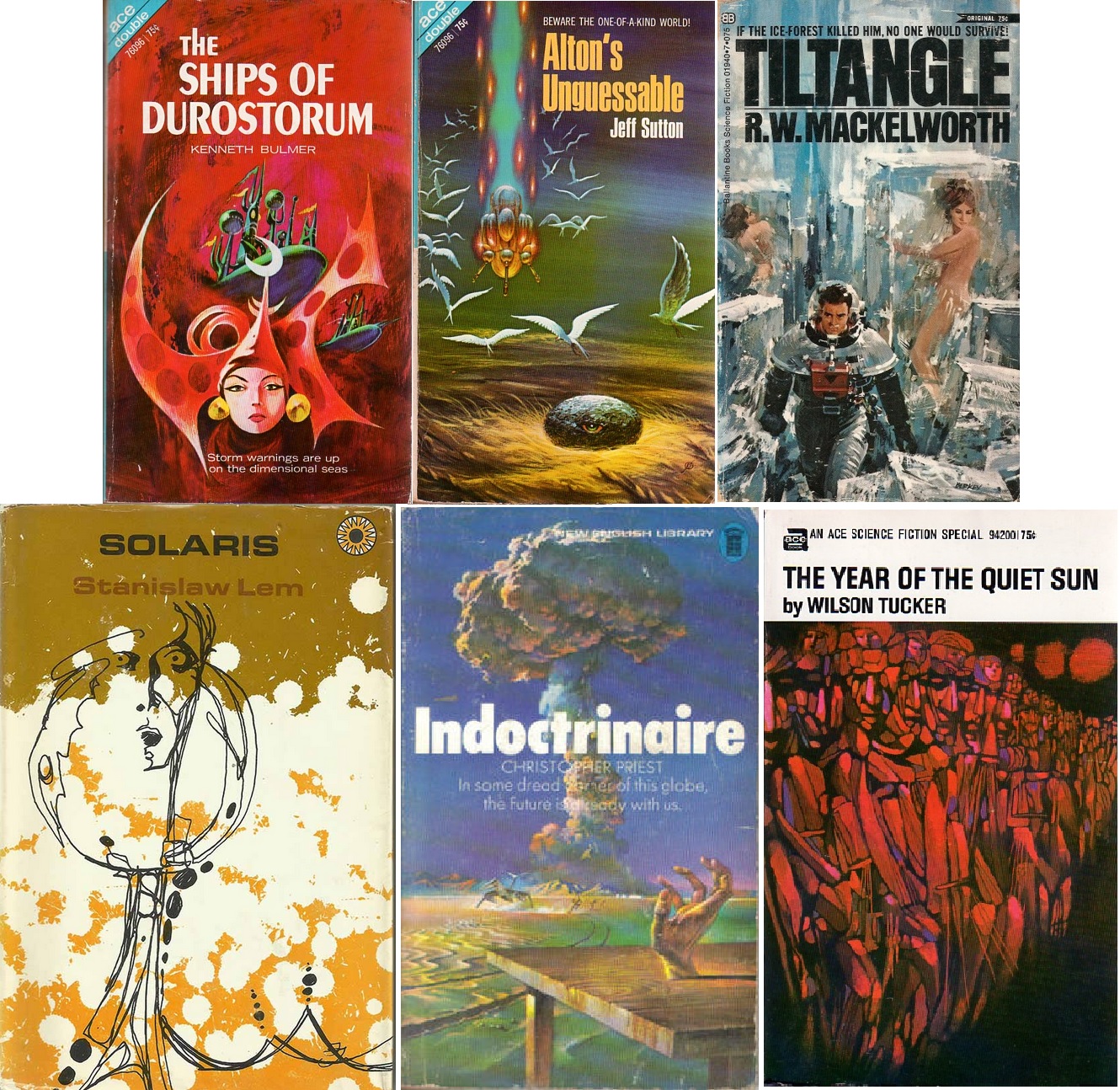

![[June 16, 1970] <i>Solaris</i>, <i>Year of the Quiet Sun</i>…and a host of others (June 1970 Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700616covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 12, 1970] Something Good! and Nothing Terrible (July 1970 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/amz-0770-cover-672x372.png)

![[May 28, 1970] A pair of Saras: <i>Flower of Doradil</i> and <i>A Promising Planet</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/ace_double-672x372.png)

![[May 20, 1970] <i>Circus of Hells</i>, <i>Tau Zero</i>, and <i>Vector</i> (May 1970 Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/700520covers-672x372.jpg)