by Kaye Dee

Returning to university kept me pretty busy in February, so I knew I wouldn’t have time to write, but this past month has seen yet more leaps forward in space exploration with the world’s first spacewalk and the launch of NASA’s first manned Gemini mission.

Soviet Space Achievements

It’s hard to believe that it’s just under four years since Yuri Gagarin rocketed into orbit as the first man in space. In that short time we’ve seen six flights in the Soviet Union’s Vostok program, including the first dual missions with two space capsules in orbit at the same time, and the first woman in space (how I’d love to meet Valentina Tereshkova!)

The first man and the first woman in space, Soviet cosmonauts Yuri Gagarin and Valentina Tereshkova

Just last year, the USSR gave us the first flight of its new Voskhod spacecraft, carrying a crew of three. At that time, my fellow writer, Gideon Marcus asked, what would the Soviets follow it up with? (see October 1964 entry)

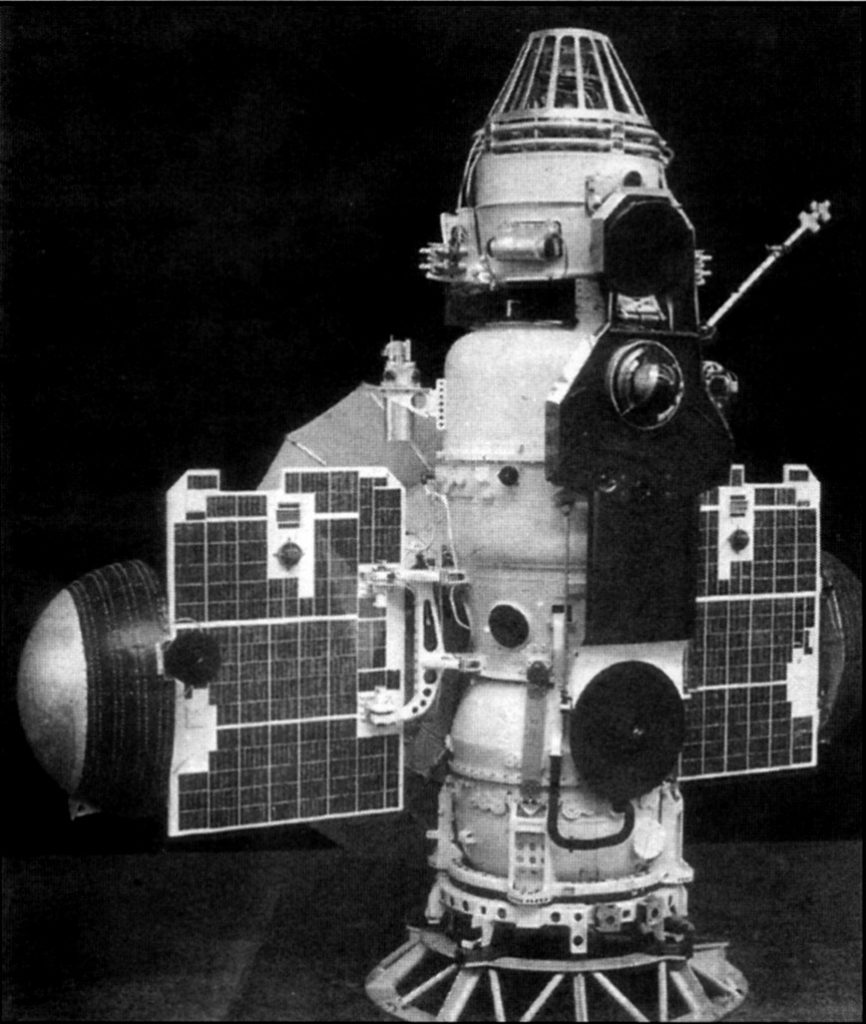

Now we know. On March 18, the USSR launched a new Voskhod mission that has once again denied the United States a significant space first. This time, the Voskhod 2 mission included the world’s first spacewalk – about a year ahead of when NASA has anticipated accomplishing the same feat.

A Mystery Spacecraft

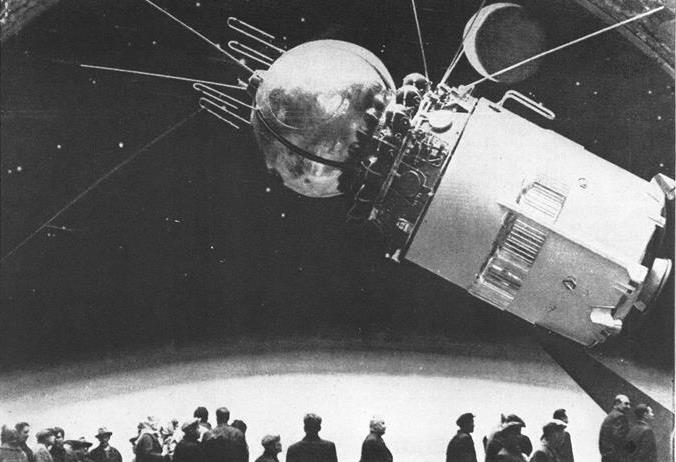

One of the few Voskhod images released so far, showing the inside of Voskhod 1. The orange cladding may be covering up many of the spacecraft's instruments

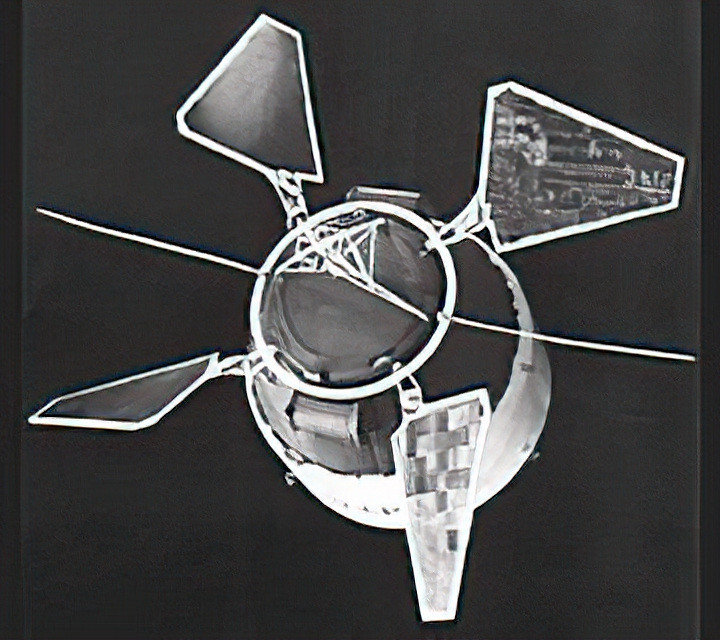

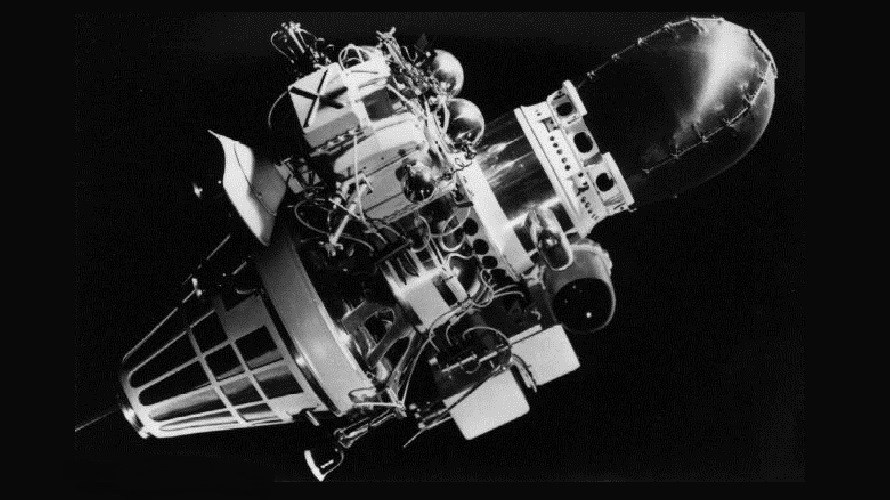

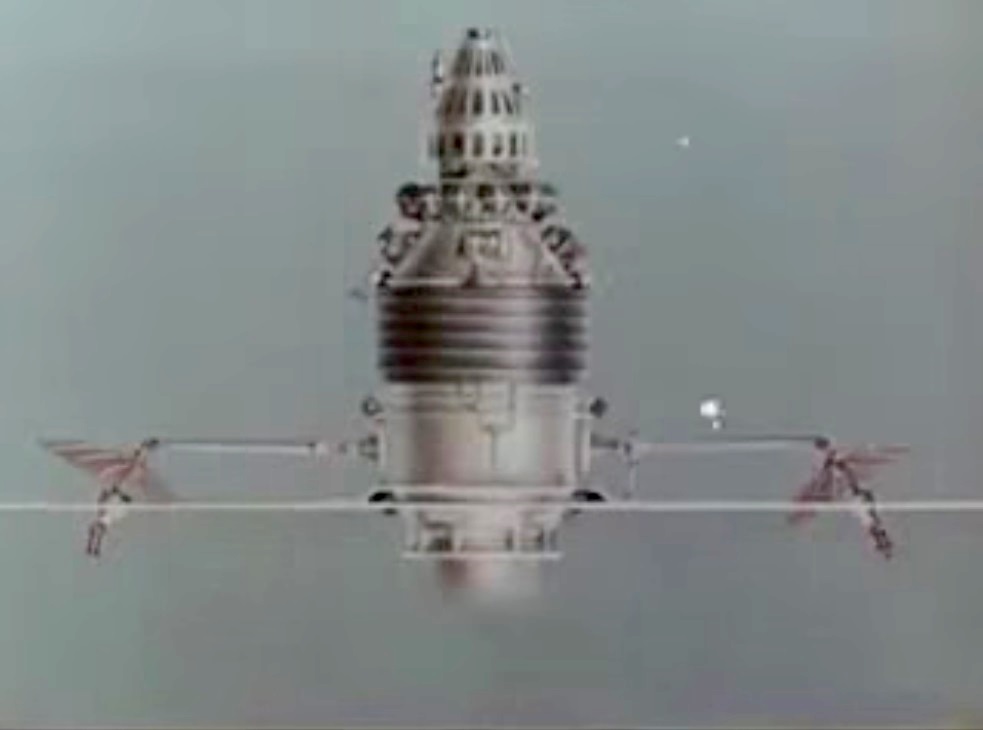

We don’t know a lot about the Voskhod spacecraft as the Soviet Union has released few pictures of it or statistics about it. It clearly must be substantially larger than the Vostok, since it has proved capable of carrying three people on its first flight, and two cosmonauts plus an airlock device on the recent spacewalking mission. We do know that, according to official figures, Voskhod 1 weighed 11,728lb, while Voskhod 2 weighed in at 12, 527lb – presumably because of the extra weight of the airlock it carried.

Newly Revealed Cosmonauts

The crew for this historic space flight were two cosmonauts whose names were previously unknown to us in the West: Colonel Pavel Belyayev, the mission Commander, and Lt. Colonel Alexei Leonov, who performed the actual spacewalk, or Extravehicular Activity (EVA) as NASA terms it. Leonov’s name will now go down in the history books as the first person ever to step outside a spacecraft into open space. Soviet cosmonaut biographies don’t really tell us very much, but both men are apparently Air Force fighter pilots, and are married with children. At 39, Col. Belyayev is the oldest person so far to make a space flight; he is also the oldest and highest ranking of the cosmonauts we know about.

Official TASS photo of Belyayev (left) and Leonov (right) with Yuri Gagarin at a radio interview after their historic flight

Onboard Airlock

Voskhod 2 was launched at 07.00GMT (5pm Australian Eastern Standard Time) and it was just 90 minutes later, on the second orbit, that the spacewalk took place. At the time, Voskhod 2 was about 300 miles above the earth – the highest orbit by a manned spaceflight to date. Soviet sources describe the airlock that Leonov used to exit the ship as being mounted on the outside of the spacecraft and entered from the Voskhod cabin via a hatch. After the completion of the spacewalk, the airlock was jettisoned before the ship returned to Earth. Because the spacewalk would expose the crew to the vacuum of space if the airlock malfunctioned, both cosmonauts wore spacesuits for the duration of the mission, unlike the Voskhod 1 crew, who made their space flight in lightweight suits, which would seem to be an indication of Soviet confidence in the performance of the spacecraft.

Belyayev (left) and Leonov (right) in their spacesuits on the way to the launch site. Voskhod 1 cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov is between them

Stepping into the Void

According to the TASS news agency, Lt. Col. Leonov spent 20 minutes “in conditions of outer space”. Since his actual spacewalk lasted about 10 minutes, the rest of the time must have been spent in the airlock. I’ve heard a rumour from my friends at the WRE that the spacewalk did not go as smoothly as the Soviets would like us to believe, and that Leonov actually had some difficulty re-entering the airlock, which might explain the times reported by TASS. But stories of Soviet coverups of problems with their cosmonaut program occur after every mission, so it’s hard to know quite where the truth lies in this instance.

Lt Colonel Alexei Leonov floating in the void of space during the historic first spacewalk, seen in frames from the film taken by a camera mounted on Voskhod 2

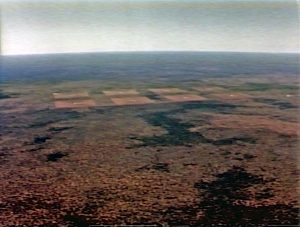

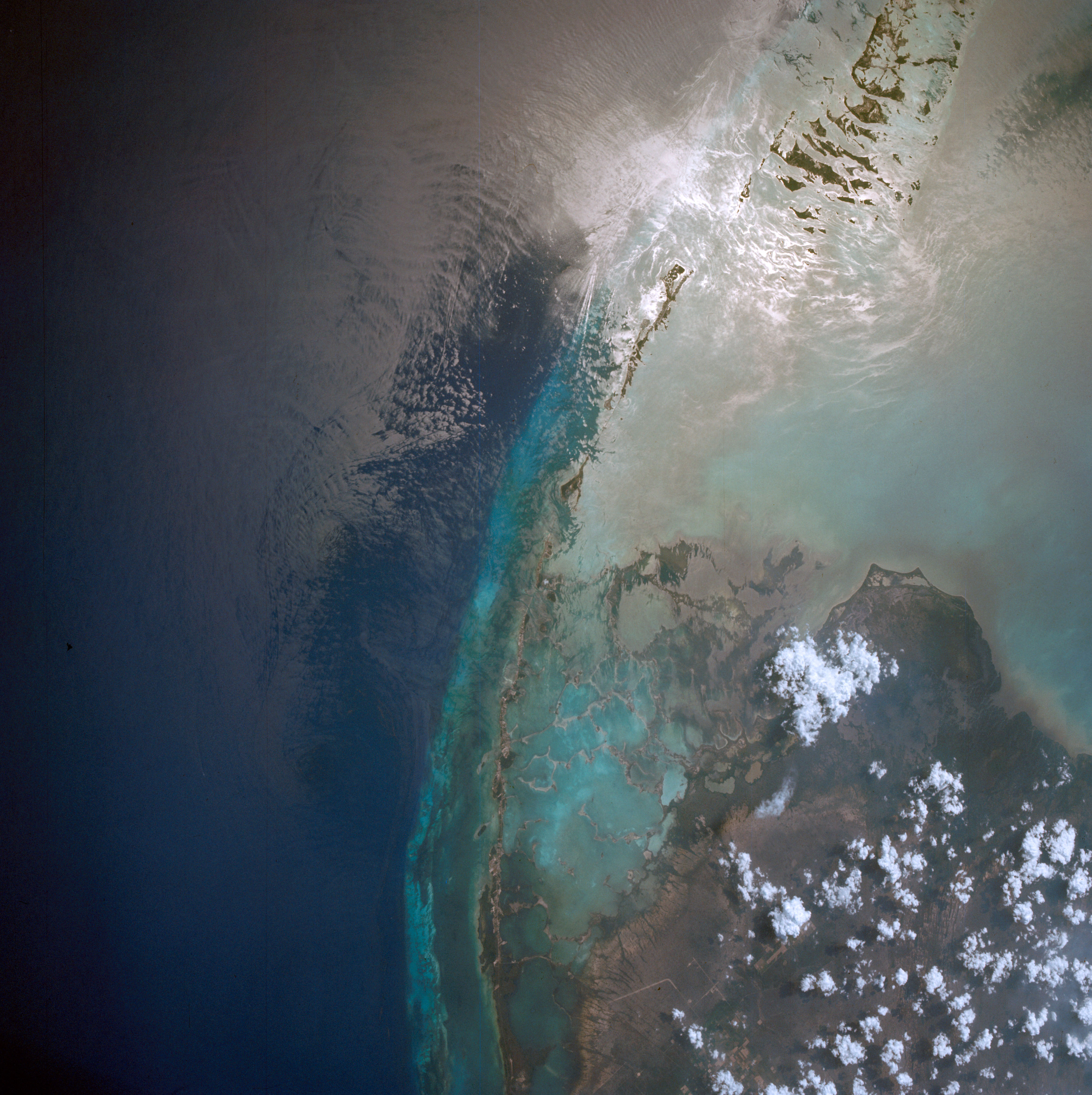

Whether he had a problem or not, Leonov spent about 10 minutes floating in the void, attached to Voskhod 2 by a long umbilicus, to prevent him drifting away. His breathing oxygen was supplied from a tank on his back. Leonov said that he could look down and see from the Straits of Gibraltar to the Caspian Sea. The spacewalk was filmed and photographed from the Voskhod and I imagine that very few of the readers of this article will not have seen the breathtaking footage of Leonov somersaulting and making swimming movements as he floats in space with the Earth behind him (actually below, of course).

Problems in Orbit?

Voskhod 2 completed 17 orbits before returning to the Earth on 19 March, but there was a mysterious silence from Moscow about the mission after the 13th orbit, which has led to some speculation that there was a problem with the spacecraft, especially as it was not until about five hours after the crew had landed in the vicinity of Perm, west of the Ural Mountains, that their safe return was reported. Belyayev is reported to have brought the Voskhod back to Earth using manual controls. Although official statements said that this was part of the planned research programme, it might also be a hint that the mission experienced problems.

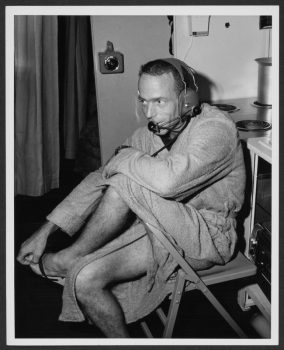

Official TASS photo of Leonov (right) and Belyayev (left) after their return from the Voskhod 2 mission. Leonov is holding folders containing congratulatory messages

But whatever problems the mission may have encountered cannot detract from Lt. Col. Leonov’s historic achievement in making the first spacewalk, a technique that will be needed to advance future space activities. I wonder what new surprises Voskhod 3 will bring….

The Latest ELDO Test Flight

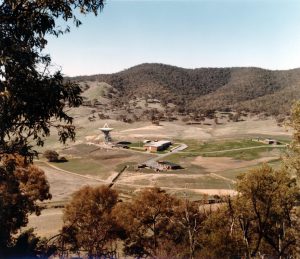

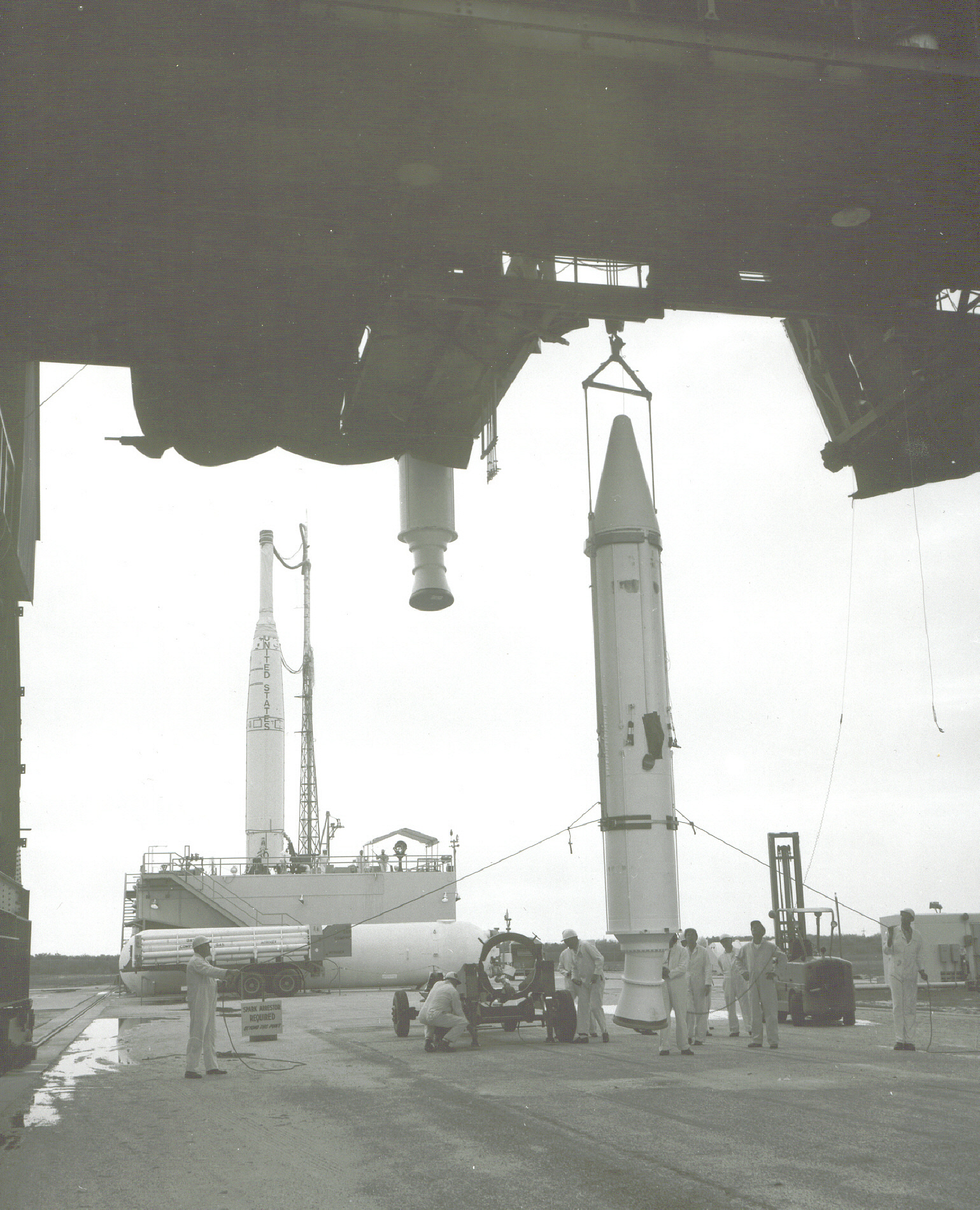

On 22 March, the ELDO program at Woomera also took another step forward with the third successful flight of the Blue Streak first stage of the Europa launcher. Launched at 8.30am local time, the rocket flew 985 miles, reaching a maximum altitude of 150 miles. This flight completes the first phase of the launcher development program: the next phase will begin with an all-up test of a live first stage with dummy upper stages.

The Blue Streak first stage for the ELDO Europa vehicle on the pad awaiting launch

America hits a Double

by Gideon Marcus

Three for Three

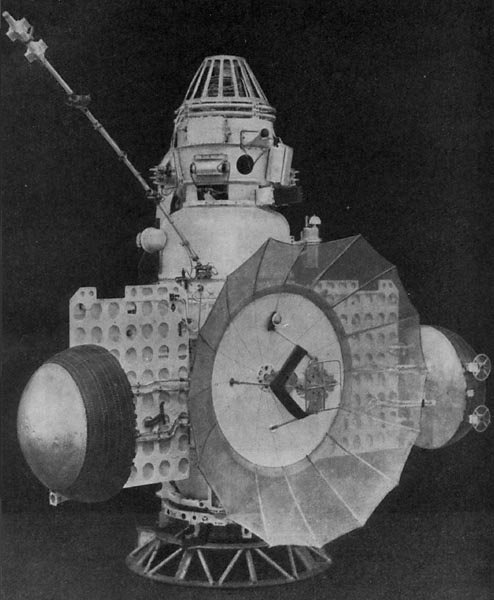

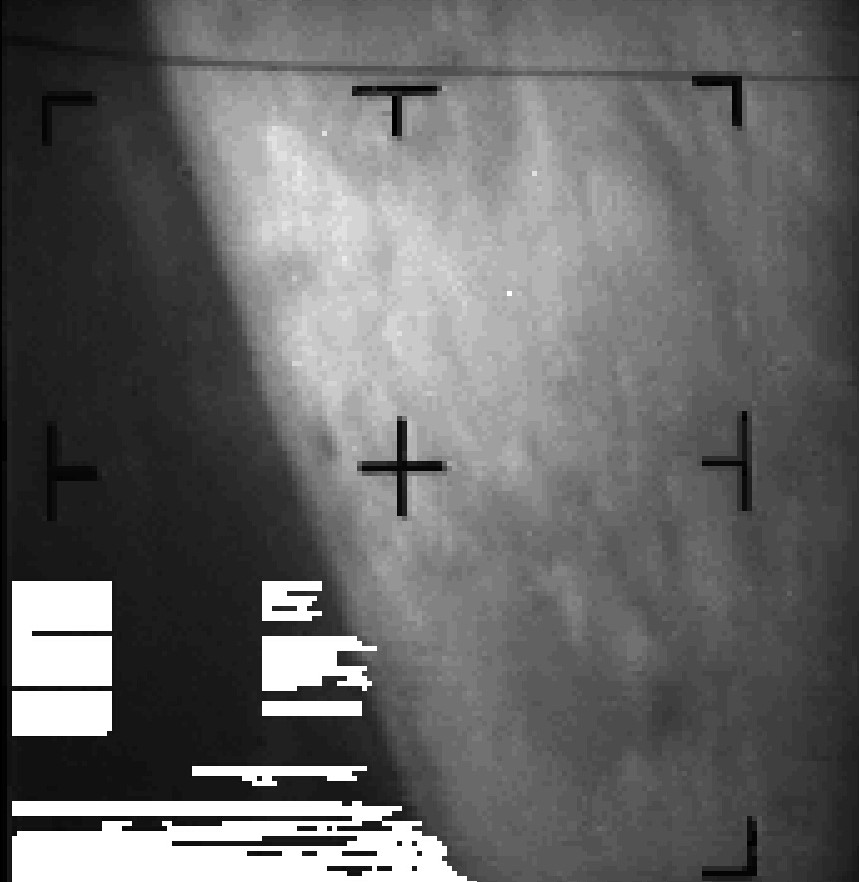

Despite the clear success represented by Voskhod 2, it would be folly to overlook the fact that it has been a tremendous week for NASA. The Ranger program, once the most ill-starred of NASA endeavors, has just completed its third successful mission in a row. Less than six hours ago, at 3:08 AM PDT, Ranger 9 crashed into the crater Alphonsus in the lunar highlands.

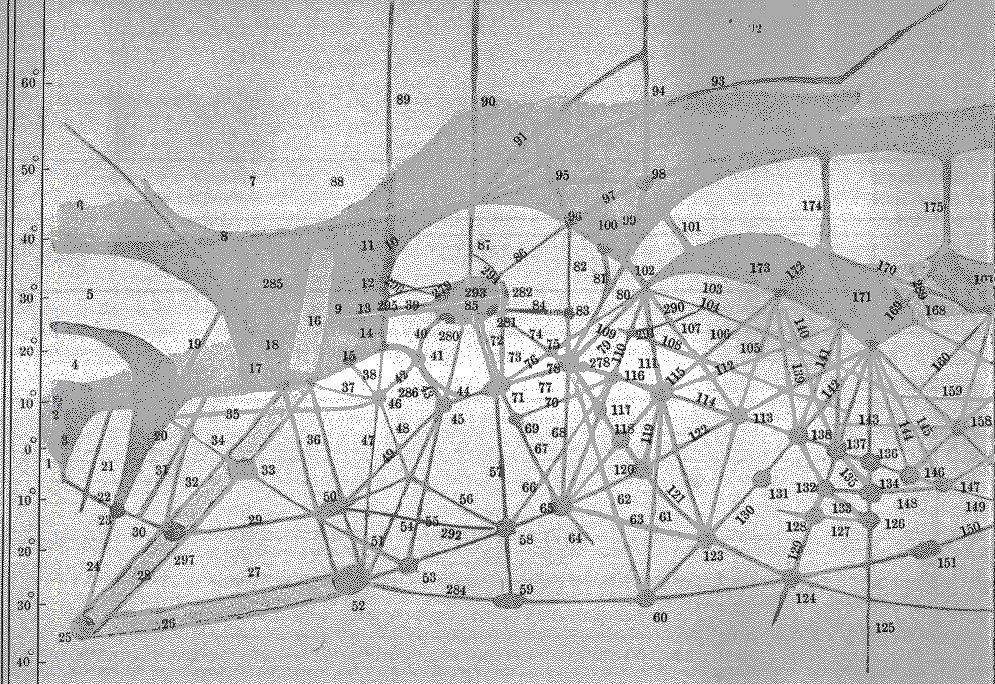

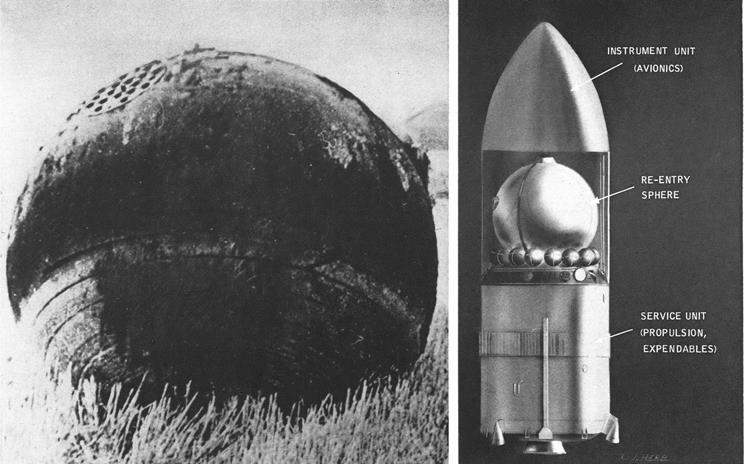

The prior two successful Rangers, 7 and 8, were largely handmaidens to the Project Apollo. They returned thousands of photographs of potential landing sites for the crewed lunar program. Ranger 9, on the other hand, was the first mission with a primarily scientific aim. In order for us to understand the Moon, its construction, and its history, we need close-up information on as many different types of terrain as possible — and no two regions of the Moon are more distinct from each other than the mountains of the lunar highlands and the relatively flat Maria or "seas". Alphonsus is particularly interesting as it has a large central peak that may be evidence of lunar vulcanism from an ancient period.

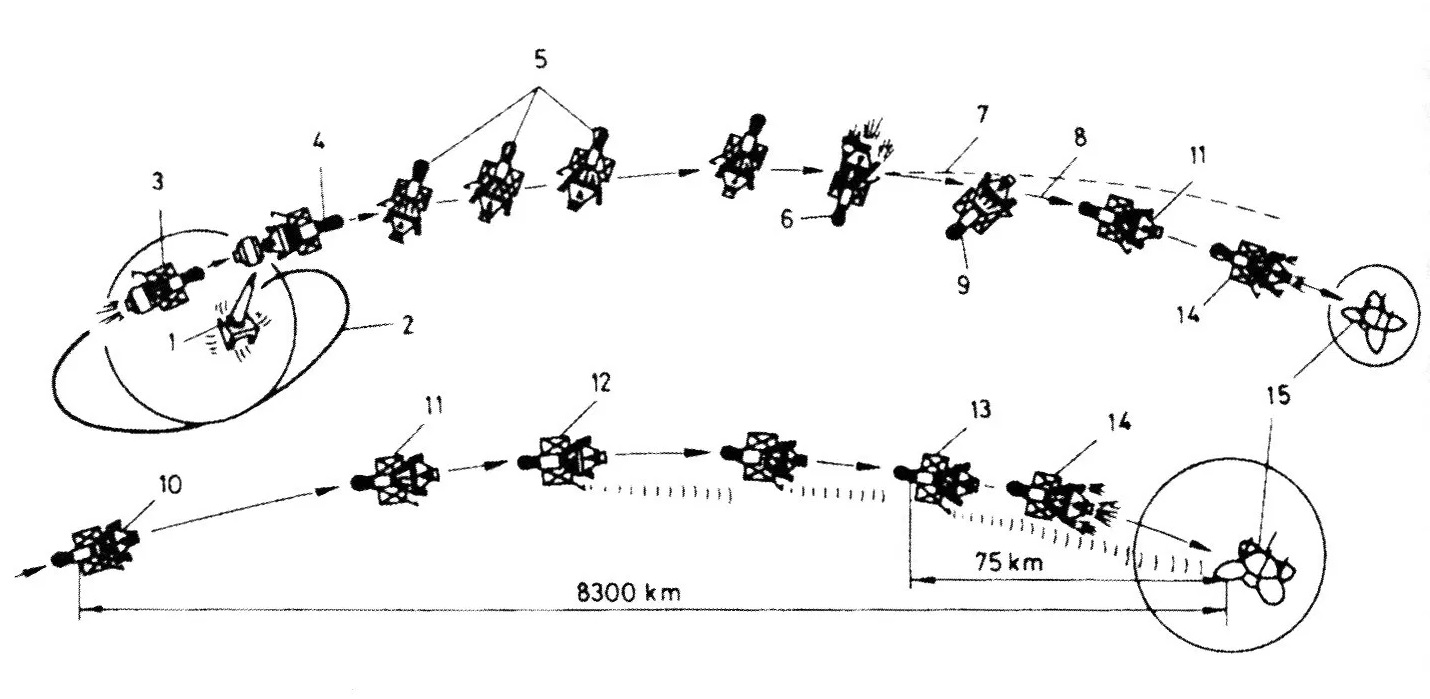

Launched at 1:37 PM PDT on March 21, the Atlas Agena carrying Ranger 9 quickly disappeared into the cloudy sky. The reliable booster's aim was true, propelling the spacecraft first into Earth orbit, and then off toward its final destination. The next day, Ranger fired its own engines, correcting its course to mathematical perfection.

Today, at Impact -20 Minutes, Ranger 9 warmed up its television cameras. Images began appearing at the JPL auditorium…and around the nation, broadcast to anyone who was up to see it (and who had an online TV station to tune into!) This was the first time a robotic mission had been simulcast, and it was very exciting. Now if only they could time their missions to be more accommodating to the aged thirty-nine year old science writers who cover them…

There were originally supposed to be 12, or even 15 Rangers, but because it took so long for them to work properly, there are now more advanced missions that are superseding them, namely Lunar Orbiter and Surveyor. This is just as well. While Ranger has been a triumph of engineering and science, bearing unexpected dividends in the successful spinoff spacecraft, Mariner 2, there is only so much one can learn from TV pictures. Indeed, initial reports suggest that while Ranger 9's photos discovered new craters within Alphonsus that might be evidence for vulcanism, as Dr. Harold Urey quipped, it won't be until we have chemists on the Moon that we can draw solid conclusions.

In any event, bravo NASA, and bravo Ranger.

Two in Three

After the spectacular mission of Comrades Tereshkova and Bykovsky in June 1963, there was a long pause in crewed spaceflight. The Mercury program had ended in May '63 with the day-long mission of Gordo Cooper in Faith 7. Talk of extending Mercury was poopooed (though you can get an idea of what might have happened if you read the excellent novel, Marooned). For more than a year, as Mercury's 2-seat successor, Gemini, suffered delay after delay, we waited for Khruschev's shoe to drop.

And the Soviets did beat us back to space with their three-man flight last October, though the success of that mission was somewhat eclipsed by the Soviet coup that took place just a couple hundred miles beneath the orbiting space capsule. Voskhod 2, with its remarkable space walk, only seems to further the Soviet lead.

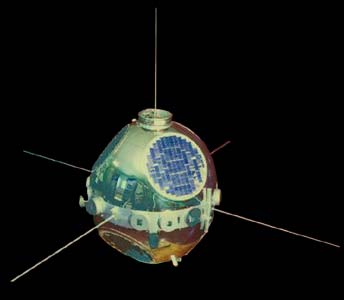

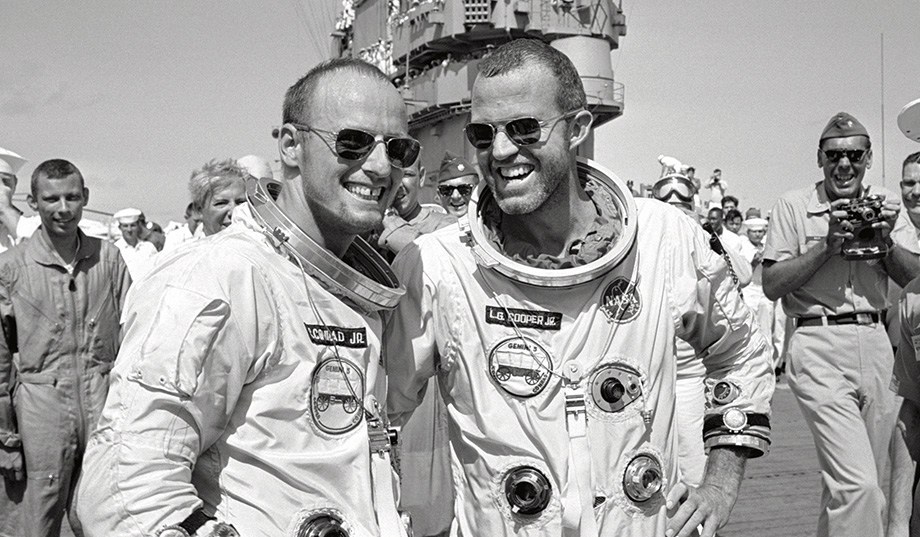

Yet the American turtle still has ambitions to beat the Red Hare. The third Gemini mission (the first and second were uncrewed test flights) had been planned for this month for some time, and yesterday morning, Gemini 3 took off from Cape Canaveral carrying astronauts Gus Grissom and John Young for a three-orbit test flight.

A lot has changed since John Glenn's pioneering three-orbit flight in Friendship 7, just three years ago. Both Grissom and Young were kept busy with a slew of biological experiments to conduct in orbit. Grissom got to conduct the very first spacecraft maneuver, firing the ship's engines once per orbit to change its altitude and velocity. Neither Mercury nor Vostok had this capability, and I haven't read anything that suggests Voskhod has it, either. Score one for the home team!

In addition to the ordinary drama that attaches to every space mission, the astronauts created some of their own. A couple of hours into the flight, as Gemini drifted along its second orbit, it was time for the astronauts to sample their carefully prepared space food. This meal was lavishly prepared by NASA scientists to be nutritious, compact, and resistant to creating crumbs that could drift into and short vital ship components.

Whereupon astronaut John Young pulled out a corned beef sandwich from his pocket, ate a bite, and offered it to his commander. Grissom took a polite nibble, commenting on the sandwich's inability to stay together, and quickly put the thing in his pocket. Apparently, this was all the brainchild of Schirra, the most renowned prankster of the Mercury 7.

Beyond this incident, the very name Grissom chose for the first crewed Gemini was something of a scandal. Christening a spacecraft has always been the privilege of its commander, and Grissom, sensitive to the fate of his last ship, chose an appropriate name: "Molly Brown." This, of course, was the name of the eponymous character from The Unsinkable Molly Brown, a popular broadway musical about a survivor of the Titanic disaster.

NASA felt that the name lacked dignity and insisted on a change. Grissom dug in his heels, insisting that if he had to change the name, it would be to Titanic. NASA gave in.

Gemini 3 completed its three orbits without incident and reentered the atmosphere four and a half hours after leaving it. Unfortunately, Molly Brown plunged back into the atmosphere somewhat off course. Grissom tried to steer the capsule (such as it is possible to maneuver a shuttle-cock shaped craft) closer to the Atlantic recovery fleet, but the craft ultimately splashed down some 84 kilometers short. It took a good half hour for the carrier, U.S.S. Intrepid, to arrive. In the interim, Grissom and Young sweltered, the commander unwilling to open the capsule and risk another swamped spacecraft. It is my understanding that Molly Brown is still decorated with Schirra's sandwich…

Minor issues aside, Gemini 3 was a fully successful flight, officially man-rating the Gemini spacecraft. The next mission, currently scheduled for late spring, will feature the American version of the vacuum shuffle. The first American spacewalk was originally planned for next year, but Leonov's jaunt changed all that. Sometimes the rabbit gives the turtle a little goose…

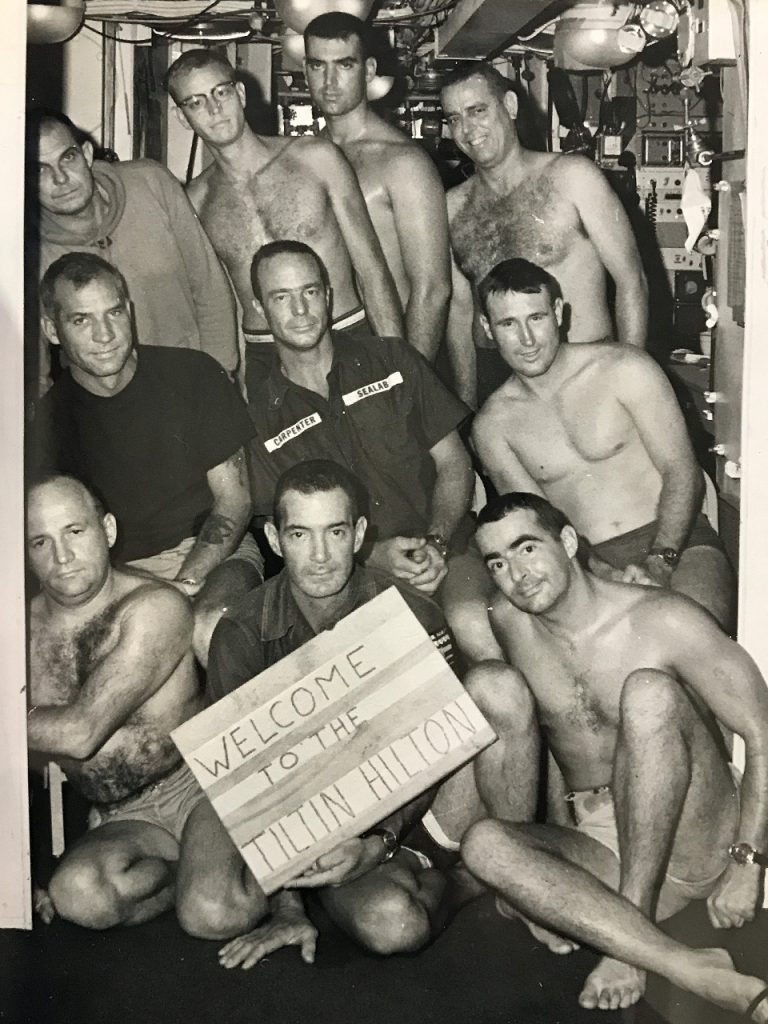

(If you're wondering why the second Mercury astronaut got the honor of commanding the mission, it's because Alan Shepard, the first Mercury astronaut, has been taken off flight status due to an inner ear disease, and astronaut Slayton, the only Mercury astronaut who hasn't flown a mission, was grounded earlier for a heart condition. I'd assumed that Wally Schirra would command Gemini 4 (Glenn retired to go into politics; Carpenter retired to become an aquanaut), and that Cooper would take Gemini 5. Apparently, however, Ed White of the second group of astronauts so impressed his peers that he will command the next Gemini mission. Because of the shifting Gemini schedules, Cooper is still taking Gemini 5, but Schirra is going after him, commanding Gemini 6.)

The Score

So there you have it. In the last six months, the Soviets have orbited five men, one of whom stepped into Outer Space. The Americans orbited just two, but they autonomously drove their own spacecraft. Meanwhile, Ranger 9 raised the total of close-up pictures of the Moon to nearly 20,000 whereas the Russians still haven't added to the handful provided by Luna 3 more than five years ago!

I guess we'll see what happens. Will the next flight be Gemini 4 or Voskhod 3?

We'll be talking about these space flights and more at a special presentation of our "Come Time Travel with Me" panel, the one we normally do at conventions, on March 27 at 6PM PDT. Come register to join us! It's free and fun…and you might win a prize!

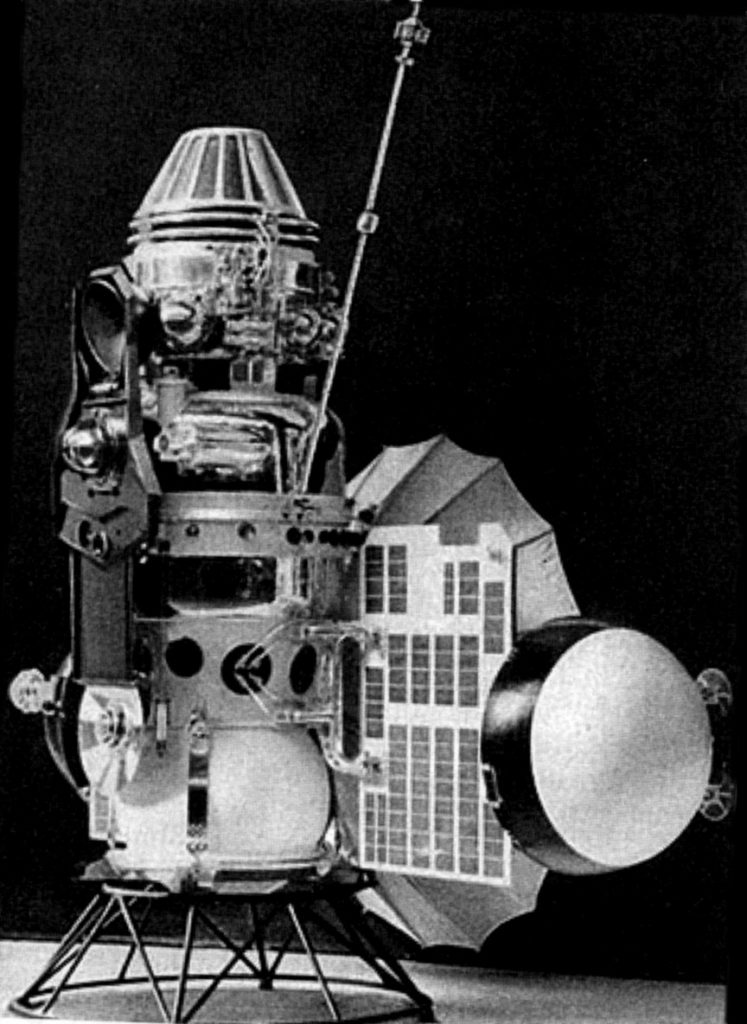

![[November 22, 1965] Keep on Exploring (Explorer-29 and 30 and Venera-2 and 3)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Venera_2-672x372.jpg)

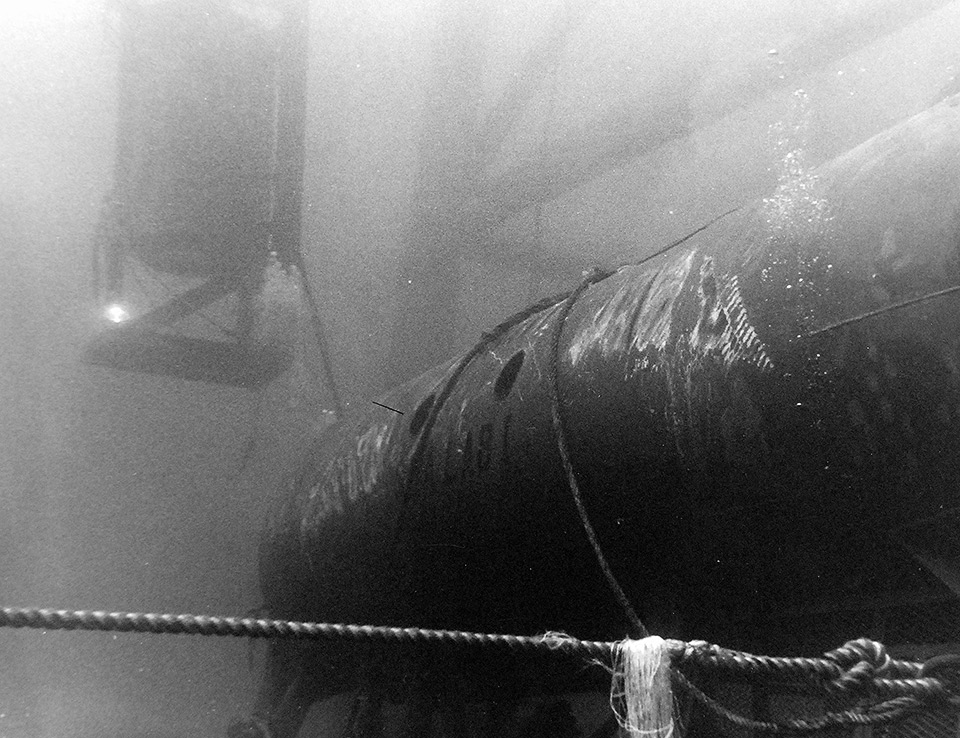

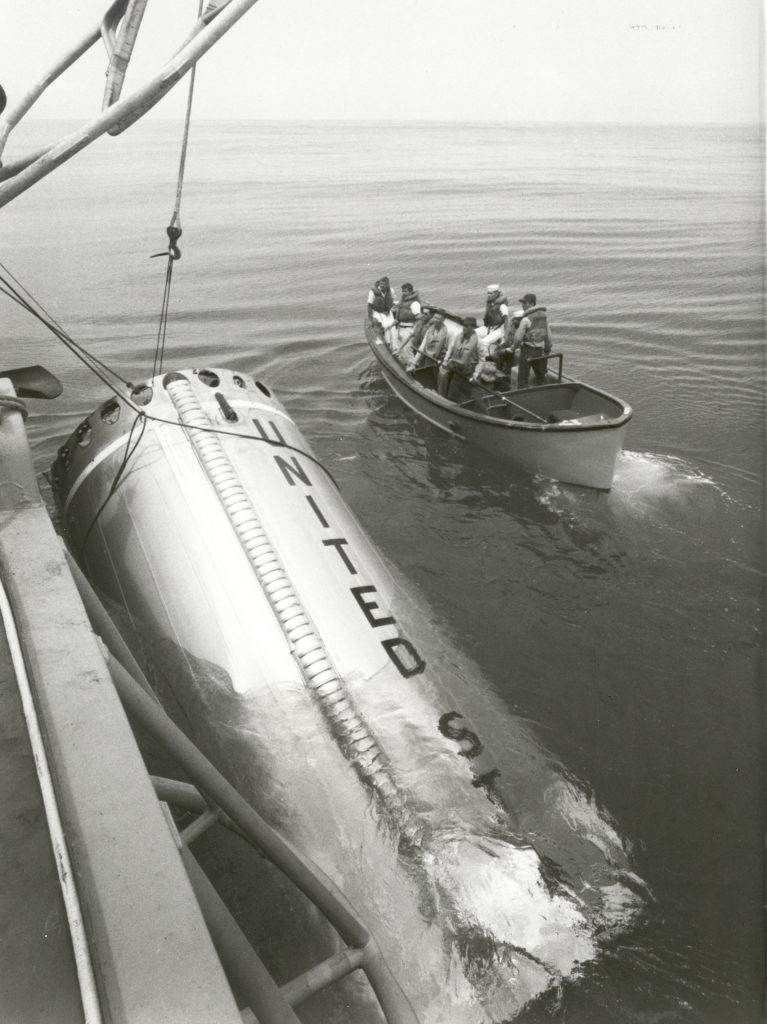

![[October 14, 1965] Taking a Deep Dive (the SEALAB project)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/SEALAB_II-672x372.jpg)

![[August 30, 1965] 8 Days or Bust! (Gemini 5's epic space mission)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Cooper-and-Conrad-672x372.jpg)

![[July 22, 1965] Do what you do do well (July space round-up)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650722proton-672x372.jpg)

![[July 20, 1965] No War of the Worlds After All? (Mariner IV reaches Mars)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/mariner04-640x372.gif)

![[June 8, 1965] A Walk in the Sun (the flight of Gemini 4)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650608Gemini_Four_patch-471x372.jpg)

![[May 30, 1965] Ticket to Ride (May space round-up)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650530pegasus2-672x372.jpg)

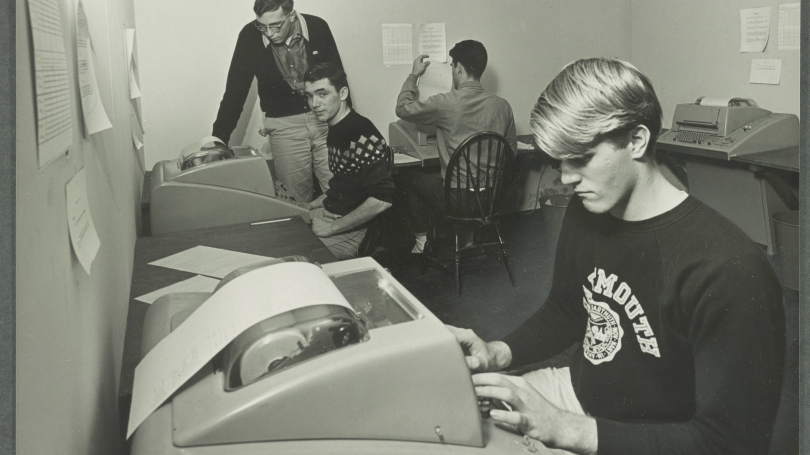

![[May 10, 1965] A Language for the Masses (Talking to a Machine, Part Three)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/650510jennifer-662x372.jpg)

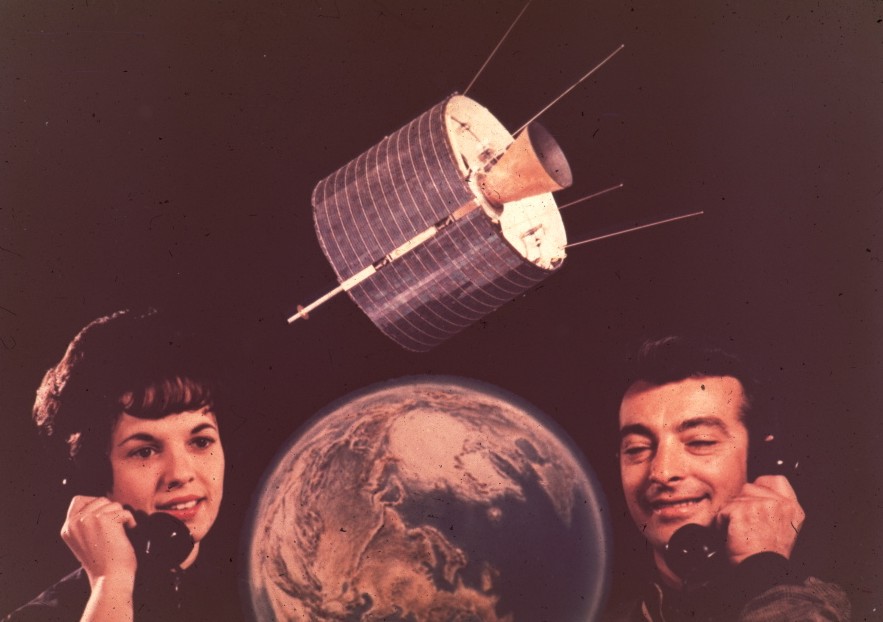

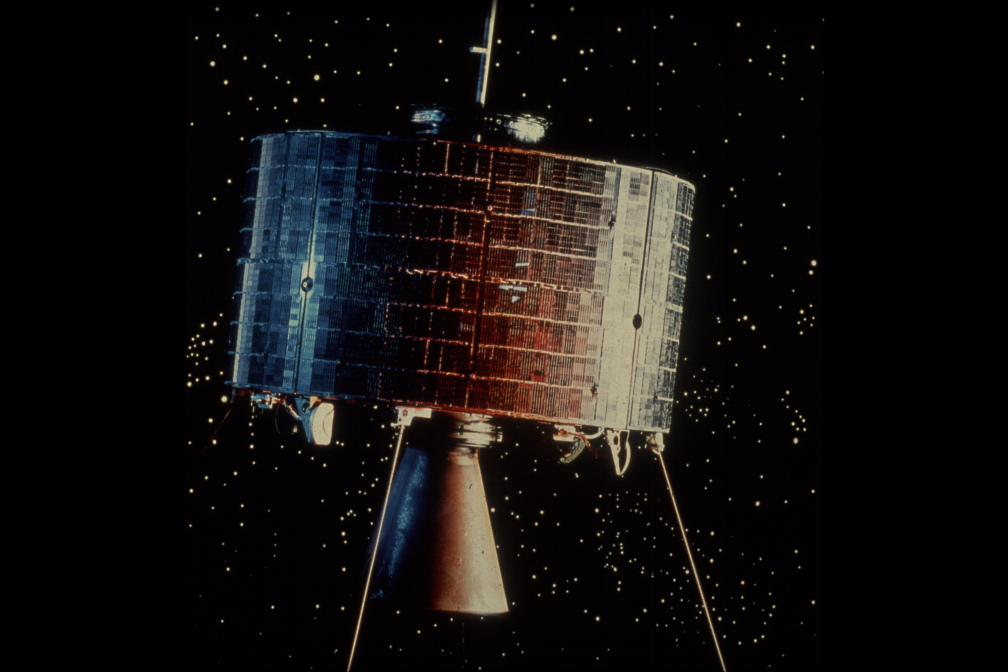

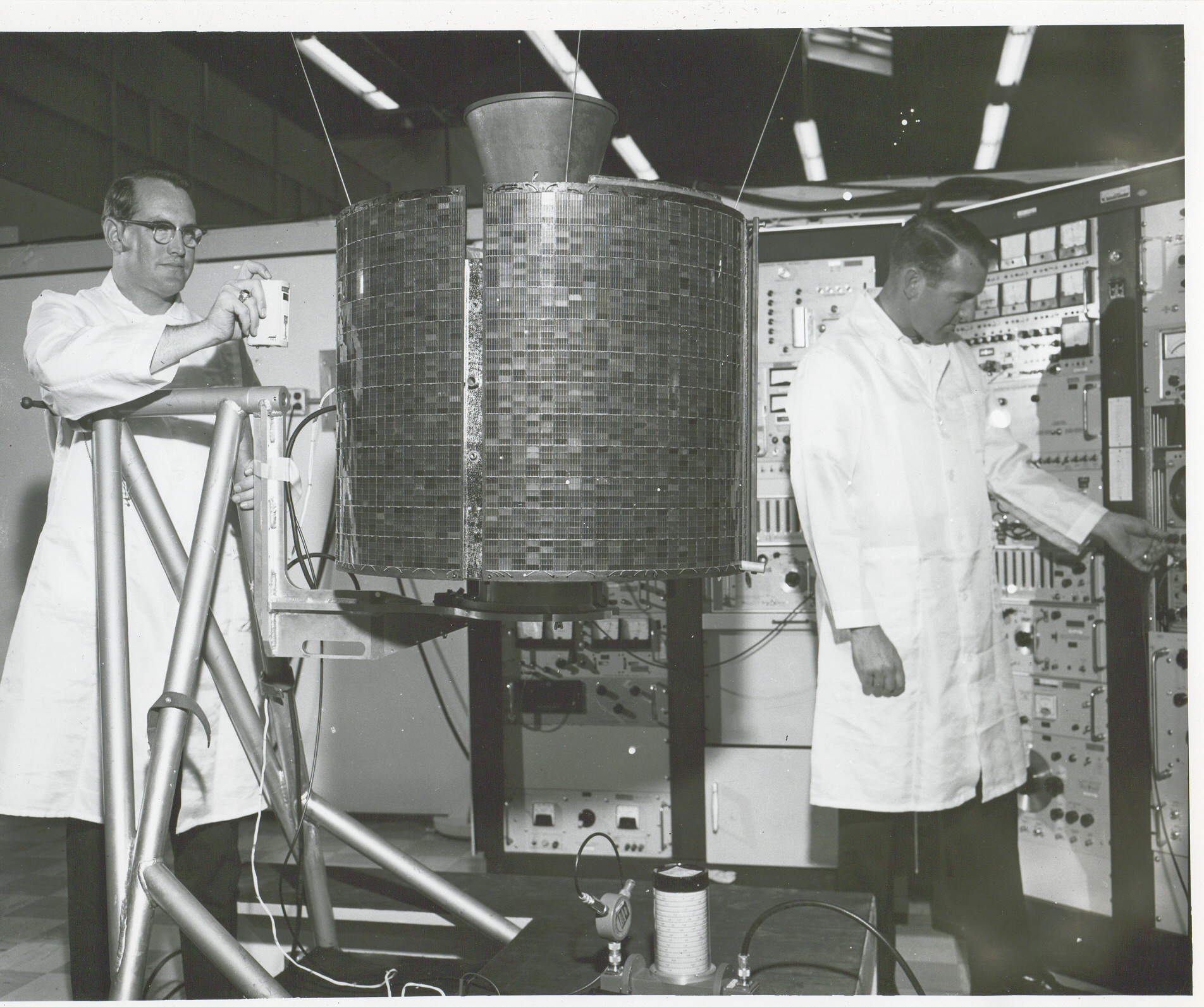

![[April 6, 1965] The Early Bird Catches the Worm (INTELSAT 1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Intelsat-1-1-620x372.jpg)

![[March 24, 1965] New Leaps Forward in Space (Voskhod 2, Europa F-3, Ranger 9, and Gemini 3)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Voskhod-spacewalk-397x372.jpg)