by Kaye Dee

by Kaye DeeThe recent launch of the ESRO 2B scientific satellite on 17 May (more on that below) reminds me that it has been a while since I wrote anything about the European launcher development programme being carried out in Australia. There have also been major developments in Europe’s space plans over the past few months, which look like they will significantly change the future of the European space programme.

For readers in the United States and other parts of the world, who may not be familiar with the European space programme, let me take a few moments to introduce the major players and provide a bit of background before talking about recent developments.

For readers in the United States and other parts of the world, who may not be familiar with the European space programme, let me take a few moments to introduce the major players and provide a bit of background before talking about recent developments.Cousins Rather Than Siblings: ELDO, ESRO and CETS

The two most important space bodies in Europe are the European Space Research Organisation (ESRO) and the European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO). ESRO’s focus is on developing scientific satellites for space research. ELDO looks to develop an independent satellite launch capability for Europe through the Europa rocket, conducting its test flights from the Woomera Rocket Range in Australia.

The French acronym CERS stands for Conseil Européen de Recherche Spatiale

The French acronym CERS stands for Conseil Européen de Recherche SpatialeThese roles would appear to be complementary, and I have occasionally referred to ELDO and ESRO as “sister” institutions in previous articles, since they have grown up in parallel and have several member states in common. However, I’ve come to think that they are perhaps best considered as “cousins”, as they operate and forward plan quite separately from each other, resulting in a lack of co-ordination across Europe's space activities. While ELDO was established with an assumption that ESRO would be one of the customers for its launch services, ESRO has not waited for a European launcher to become available from ELDO: ESRO 2B has been launched under NASA’s auspices on a Scout vehicle from Vandenberg Air Force Base and for the foreseeable future all planned ESRO satellite launches will be on US rockets.

The French acronym CECLES stands for Conseil européen pour la construction de lanceurs d'engins spatiaux

The French acronym CECLES stands for Conseil européen pour la construction de lanceurs d'engins spatiauxMention also needs to be made of the European Conference on Telecommunications by Satellites (CETS), the third space organisation in Europe, which is playing a role in pushing for some of the proposed changes in Europe’s space plans. Unlike ESRO and ELDO, CETS is not active in developing space technologies and vehicles, but provides a forum for European Post, Telegraph and Telecommunications agencies (PTTs) to consider the role of communication satellites and discuss the European role in the INTELSAT global telecommunications satellite system.

ESRO and ELDO: Parallel Lives

Stemming from initiatives taken in 1959 and 1960 by a small group of scientists, led by Italian Prof. Edoardo Amaldi and French physicist Prof. Pierre Victor Auger, ESRO was set up in the early 1960s. Like ELDO, it formally came into existence in 1964. ESRO’s member countries are Belgium, Denmark, West Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, Spain, Switzerland, and Britain, and the organisation’s focus has been on strictly civil scientific research. Four ESRO members (Britain, France, Italy and West Germany) also have their own national space programmes.

ESRO has already developed a number of technical facilities: the European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) in the Netherlands, is the newest, opened on 3 April. ESRO has also begun to establish its own space tracking network, ESTRACK, and has its own sounding rocket launch facility, ESRANGE (established in 1964), near Kiruna, Sweden.

The opening of ESTEC on 3 April by HRH Princess Beatrix and her husband Prince Claus included the royal couple being presented with a model of the ESRO 2B satellite

The opening of ESTEC on 3 April by HRH Princess Beatrix and her husband Prince Claus included the royal couple being presented with a model of the ESRO 2B satelliteELDO, on the other hand, was very much a British initiative in 1960-61, seeking partners in Europe for the development of an independent satellite launcher that would use as its first stage the UK’s then-recently cancelled Blue Streak missile. ELDO’s member states are Britain, France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands. Australia, despite being a non-European country, is also an ELDO member because of its role providing the test launch facilities at Woomera.

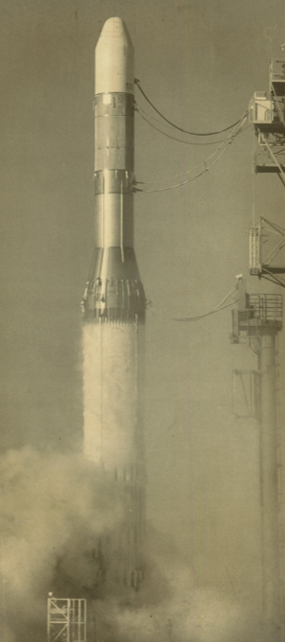

The first Blue Streak launch from Woomera in 1964, designated as ELDO F-1, the inaugural test flight of the Europa rocket's first stage

The first Blue Streak launch from Woomera in 1964, designated as ELDO F-1, the inaugural test flight of the Europa rocket's first stage Both organisations operate with a policy of “juste retour” – allocating work to industry in member countries in proportion to their share of financial contribution to the organisation.

So you can see that, unlike the US civilian space programme, under the control of NASA, and the Soviet programme, under central control from the Politburo, there are many fingers in the European space pie, with many complementary and yet competing interests and national agendas.

Not Going Up from Down Under

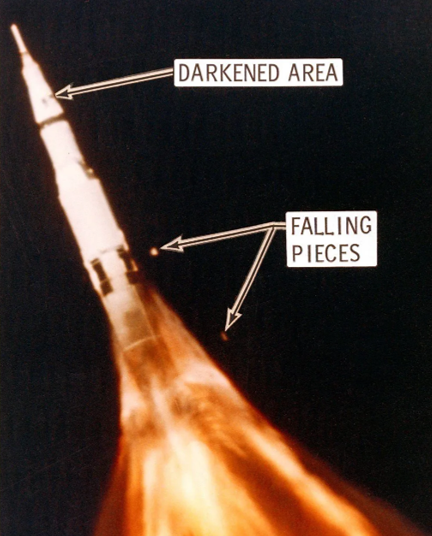

When I last reported on the ELDO programme, it was to cover the loss of the ELDO F-6 launch in August last year. At the time, I mentioned that a reflight – designated as F-6/2 – was already in planning. Scheduled for December 5, 1967, the first attempt to launch F-6/2 was aborted just 12 seconds before lift-off due to a power failure.

Although successfully launched at 6 a.m. the following morning, the second stage failed to ignite after separation from the first stage. The vehicle then crashed down into the upper reaches of the Simpson Desert, repeating the failure of Europa F-6/1. This was the second failure of an active French Coralie second stage, and an investigation is still underway to determine the cause.

Despite this failure, the next Europa launch – designated F-7 – is still planned for October or November this year as the first test flight with three active stages. Let’s hope that the issues with the second stage have been resolved by then!

Has Britain Lost Its Way in Space?

Since coming to power in the October 1964, the Wilson Labour Government has shown itself to be considerably less enthusiastic about European space activities than its Conservative predecessor. This would appear to be in large part due to the struggling UK economy, but also a response to the lack of success of Britain’s attempts to join the European Economic Community in 1963 and 67, for which UK participation in European space was supposed to be a sweetener.

In 1965, when the cost of completing the original ELDO programme had already climbed to twice the early estimates, France began to call for a revised – and more expensive – programme to develop the Europa vehicle into a launcher capable of placing satellites into geostationary orbit. Calling the Europa I launcher “obsolete”, as it can only place satellites into polar orbit, France has proposed a more sophisticated and powerful Europa II vehicle that would enable Europe to launch communications and other applications satellites without reliance on the United States (which has already given indications that it will take measures to protect its monopoly on the use of geostationary satellites).

Applications satellites, especially for international communications (as demonstrated by INTELSAT), are almost certainly the way of the future in space developments outside human spaceflight, and West Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands have agreed with the French view. This resulted in a July 1966 proposal to complete ELDO’s Europa I programme and add a Europa II development programme.

Applications satellites, especially for international communications (as demonstrated by INTELSAT), are almost certainly the way of the future in space developments outside human spaceflight, and West Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands have agreed with the French view. This resulted in a July 1966 proposal to complete ELDO’s Europa I programme and add a Europa II development programme. The British Government, however, began to express severe doubts about the “technological use and the economic viability” of the ELDO programme and opposed the French-led changes. In 1966, it signalled that Britain would not participate in any further financing of ELDO programmes after present projects were completed. Britain also reduced its financial contributions to ELDO from 38.79% (the largest contribution to ELDO’s budget) to 27%, with the difference being made up by the other four paying members (Australia being a non-paying member, on the basis of providing the Woomera facilities).

The reduction in the British financial clout within ELDO, and the desire for an equatorial launch facility, has been a factor in ELDO planning to move away from Woomera to France’s national launch facility in Kourou, French Guiana, at the completion of the ELDO I programme, anticipated in 1970. This has greatly disappointed my friends at the WRE, who spent considerable effort in preparing plans for a launch facility near Darwin, in the Northern Territory, to support an equatorial launch capability in Australia for the Europa II programme.

The first launch from France's Kourou facility, the future home of the ELDO programme, took place on 9 April this year, with the firing of a Veronique sounding rocket

The first launch from France's Kourou facility, the future home of the ELDO programme, took place on 9 April this year, with the firing of a Veronique sounding rocketBritish Space Industry Weighs In!

In November last year, a report from the National Industrial Space Committee, which represents the space interests of British industry, recommended that the British Government should not reduce, but expand its spending on space research and development, in order to stop the brain drain from the UK and obtain a share in what is already being seen as the lucrative space technology business. It recommended that spending on space-related R&D should be increased by around a 25% increase from the present $A60 million to between $A75 million and $A87.5 million said the committee.

Comments at the time from Mr Kenneth Gatland, vice president of the British Interplanetary Society, indicated that a major row was looming between industry and Government over Britain's failure to lead Europe into the commercial field of communication satellites. Although the Post Office, which controls British telecommunications, has expressed “severe doubts” about the commercial benefits of space-communication, this seems a bit strange when the Post Office is also the British signatory to INTELSAT, and the UK is the consortium’s second largest shareholder. “Government advisers”, Mr. Gatland said, “were being accused of leaving Britain high and dry through inept policies, allowing France and West Germany to benefit at Britain's expense.” Instead of the “national scandal” of Britain having spent an estimated $A124,707,500 on ELDO without any tangible end project in view, Mr. Gatland has suggested that Britain should give ELDO a target which would bring a return for the large capital investment.

Comments at the time from Mr Kenneth Gatland, vice president of the British Interplanetary Society, indicated that a major row was looming between industry and Government over Britain's failure to lead Europe into the commercial field of communication satellites. Although the Post Office, which controls British telecommunications, has expressed “severe doubts” about the commercial benefits of space-communication, this seems a bit strange when the Post Office is also the British signatory to INTELSAT, and the UK is the consortium’s second largest shareholder. “Government advisers”, Mr. Gatland said, “were being accused of leaving Britain high and dry through inept policies, allowing France and West Germany to benefit at Britain's expense.” Instead of the “national scandal” of Britain having spent an estimated $A124,707,500 on ELDO without any tangible end project in view, Mr. Gatland has suggested that Britain should give ELDO a target which would bring a return for the large capital investment. A European Symphonie?

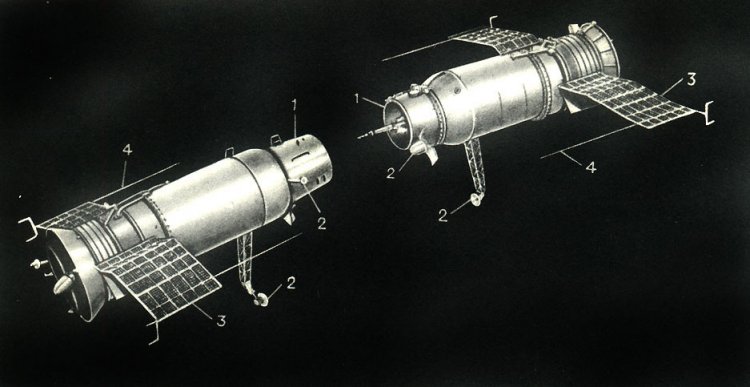

Whatever Britain’s misgivings regarding satellite communications, France and Germany are eager to move into the field of communications satellites to break INTELSAT’s monopoly on international satellite telecommunications. They have embarked on their own joint communications satellite project, known as Symphonie. As this project has taken options on two Europa II launches for its two satellites, it is, at present, ELDO's only customers! Mr Gatland has urged Britain to join France and Germany in the Symphonie project, which will promise a satellite in three to five years.

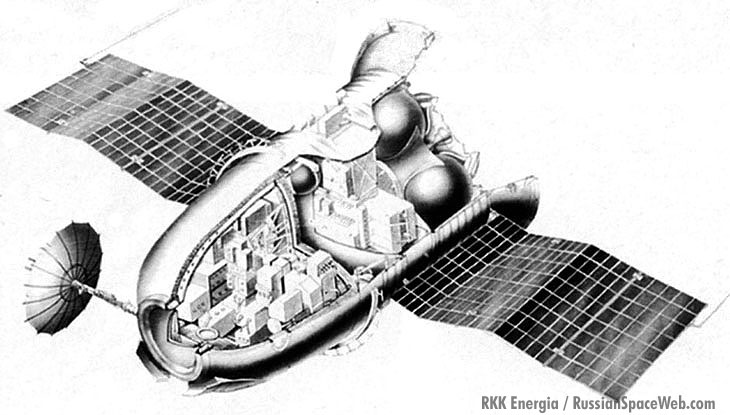

An early design for the Symphonie communications satellite, which is intended to be three-axis stabilised

An early design for the Symphonie communications satellite, which is intended to be three-axis stabilisedItaly has decided to go it alone on the development of a telecommunications satellite known as Project Sirio. The design will apparently be based on the experimental telecommunications satellite that Italy was originally going to develop for ELDO, before that aspect of the programme was cut to reduce overall costs.

ESRO is also reported to be interested in moving beyond scientific satellites into the applications satellite area, in conjunction with CETS, which has expressed interest in the development of a satellite for television distribution.

Whither or Wither, Europe?

With all this history in mind, Europe’s space plans for the future have undergone considerable change in the past few months. According to a report released in March, Europe's space club has mapped out an ambitious programme for the next 10 years that would include telecommunications satellites for television, broadcasting and telephone calls, meteorological, air traffic control and Earth resources satellites, and large numbers of astronomical and other scientific satellites. This programme, which involves a 10 per cent annual increase of expenditure on European space projects, is intended to be discussed when Science Ministers from the 17 member states of ELDO, ESRO and CETS, meet in Bonn, West Germany, in June.

However, the ambitious proposals released in March evolving as originally anticipated is now unlikely, given the most recent events. On 18 April, Britain's Labour Government announced cuts in spending on space research and cast further doubts on the future of ELDO. Although the Government indicated that it would maintain its contribution to the current ELDO programme at the existing level, it could “see no economic justification for undertaking further financial commitments to ELDO after the present programme,” which is due to conclude in 1970.

This (not totally unexpected news) was followed by an announcement from ESRO on 26 April that it was cancelling its plans for its two largest satellites scientific satellites – a major blow for European space co-operation. The two massive TD 1 and TD 2 satellites (the TD stands for Thor Delta, the intended launch vehicle), each weighing 990 lbs, were to have been built under a 100 million franc (about Aus$17,800,000) contract by an international consortium including Hawker Siddeley Dynamics of Britain, the French firm Matra, the West German group ERNO, and Saab of Sweden.

TD1, scheduled for launch in 1970, was designed to study the relationship between earth and sun. TD2, planned for launch the following year, was focused on research into solar ultra-violet radiation and electromagnetic phenomena in the upper atmosphere. The reason for the satellites’ cancellation seems to be connected with disagreements within ESRO in regard to the juste retour allocation of work for the project.

ESRO’s First satellite in Orbit!

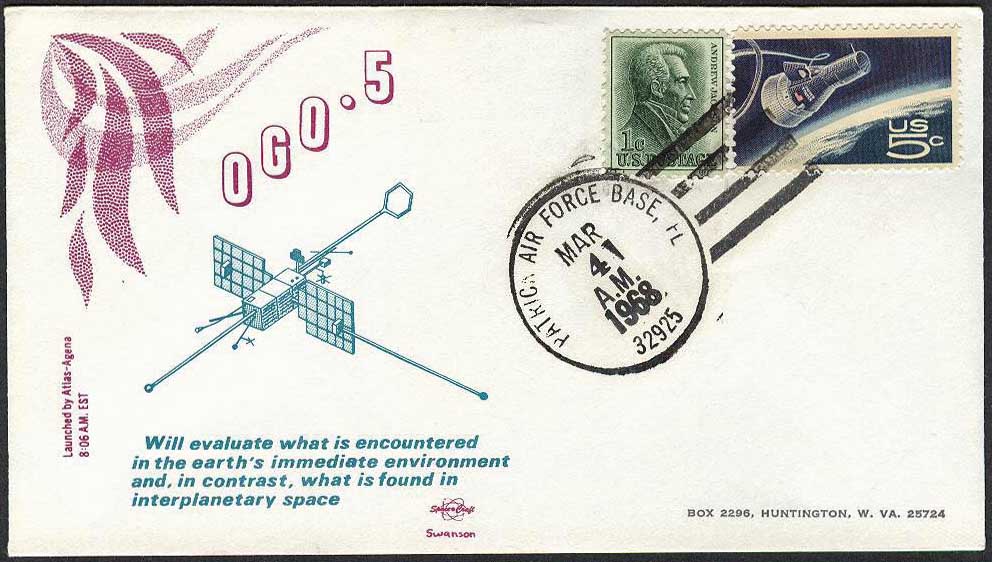

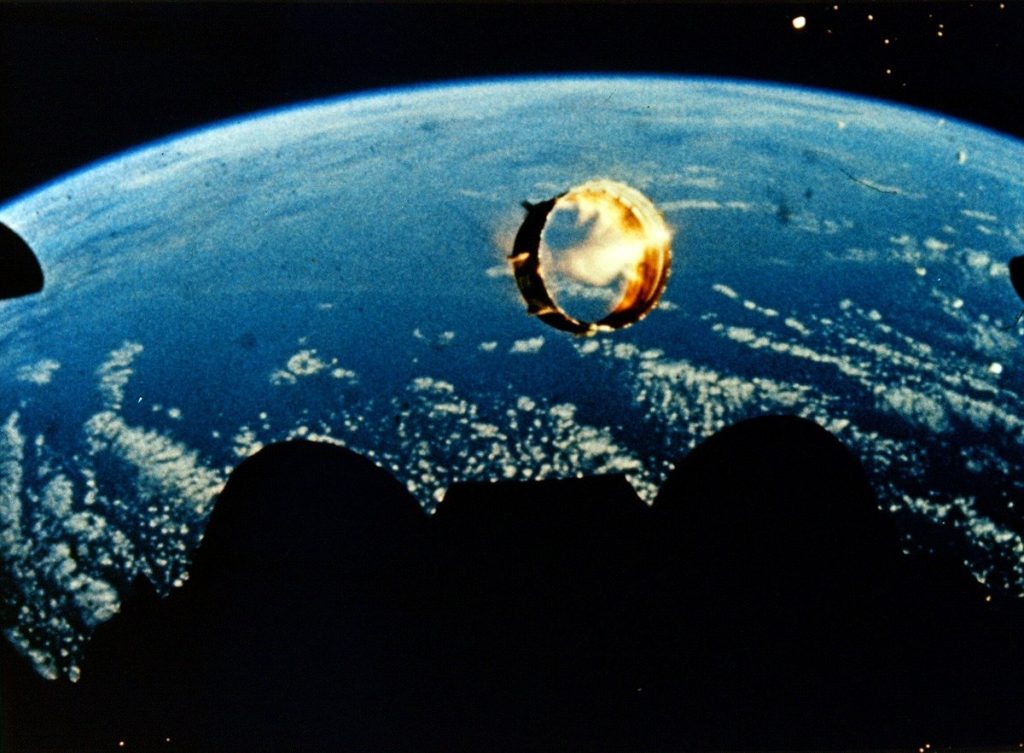

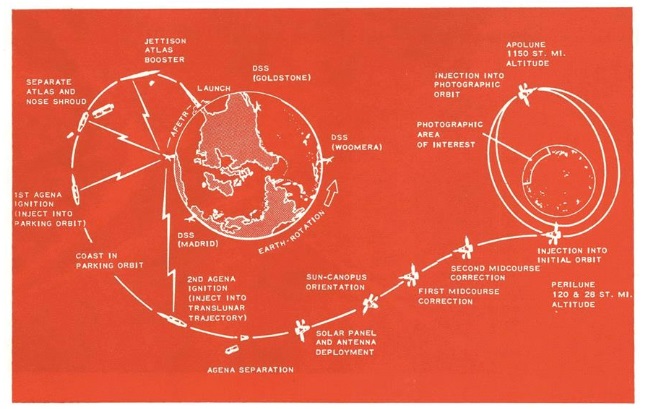

Despite the uncertainties about its future space plans, Europe is currently celebrating the launch of the first ESRO satellite to make it to orbit! ESRO-2B was launched 17 May from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California on a Scout B rocket.

Despite the uncertainties about its future space plans, Europe is currently celebrating the launch of the first ESRO satellite to make it to orbit! ESRO-2B was launched 17 May from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California on a Scout B rocket. This flight occurred almost exactly one year after the loss of its predecessor ESRO 2A on 29 May, 1967. Also launched from Vandenberg on a Scout B, ESRO 2A was lost due to a malfunction of the rocket’s fourth stage, which prevented the satellite from reaching orbit. These first European satellites were launched on Scout vehicles due to an offer from NASA to launch the ESRO's first two satellites free of charge as a ‘christening gift’ for the organisation (and no doubt to woo ESRO towards continuing with US launchers even when ELDO's Europa rockets become operational!)

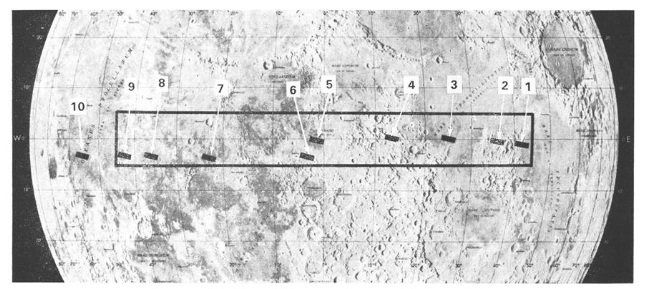

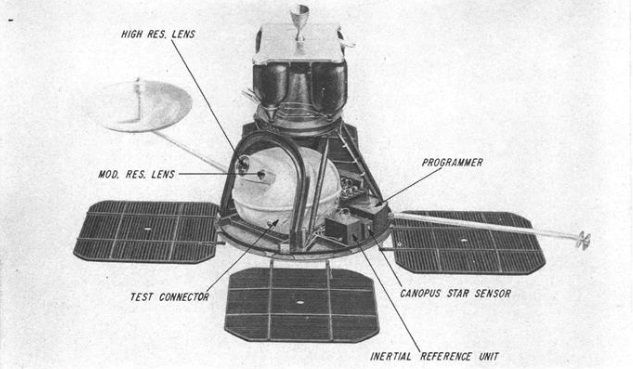

ESRO 2B, also known as Iris (International Radiation Investigation Satellite), Iris 2 and ESRO 2, is an astrophysical research satellite developed to study solar and cosmic radiation and their interaction with the Earth and its magnetosphere. This will provide continuity to the solar radiation observations of earlier satellites and continue similar particle measurements carried out by the UK’s Ariel 1 satellite. It is the first mission controlled by teams at the European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt, Germany.

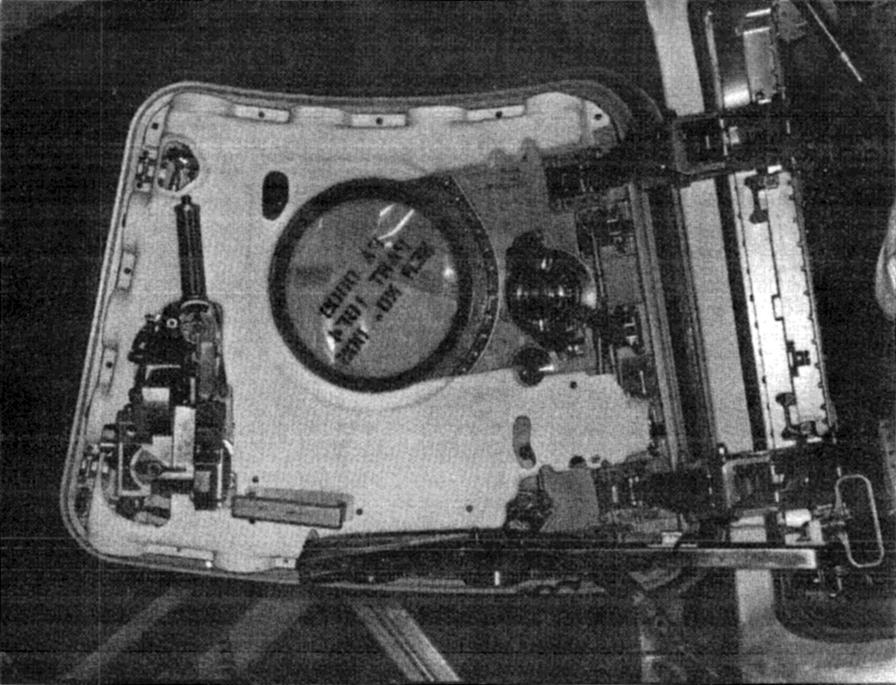

ESRO 2B being prepared for launch

ESRO 2B being prepared for launchPlaced into a highly elliptical near-polar orbit, with an orbital period of 98.9 minutes, ESRO-2B is about 33.5 inches in length, with a diameter just on 30 inches. It weighs 196 lb and is spin-stabilised, with a spin rate of approximately 40 rpm. The satellite is powered by 3456 solar cells on the outer body panels, supplemented by a nickel/cadmium battery. The satellite carries the same seven instruments as its lost predecessor: to detect high-energy cosmic rays, determine the total flux of solar X-rays, measure trapped radiation, investigate Van Allen belt protons and cosmic ray protons. And if you’re wondering why ESRO 2B is the first European satellite and what happened to ESRO 1, the simple answer is that ESRO 1 has yet to be launched! Difficulties in the development of the payload for the polar ionospheric satellite ESRO 1, designed to study how the auroral zones responded to geomagnetic and solar activity, meant that it was eventually agreed to launch ESRO-2 ahead of it. ESRO 1 is due for launch around October this year, so we here at Galactic Journey will cover its story soon.

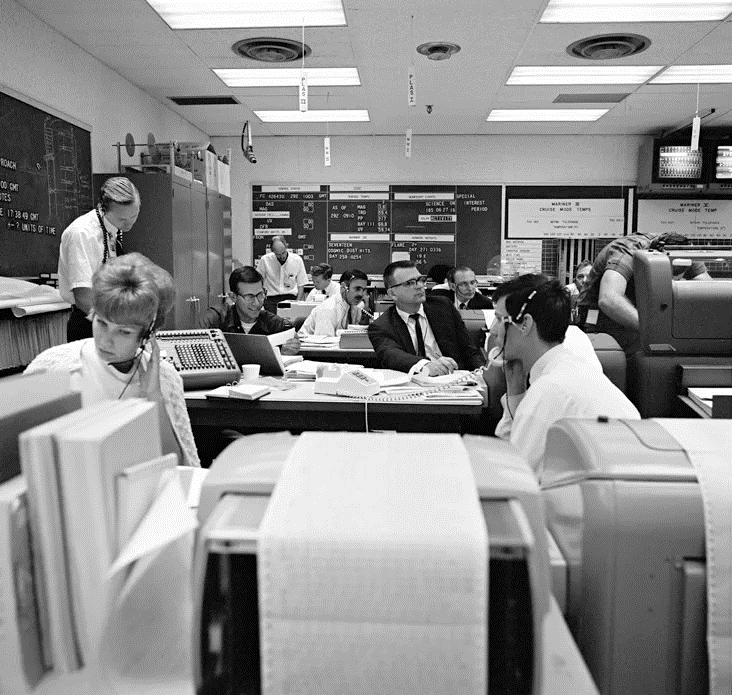

ESRO 2B being tracked at the ESOC mission control centre

ESRO 2B being tracked at the ESOC mission control centre

![[MAY 26, 1968] EUROPA AD ASTRA (EUROPEAN SPACE UPDATE)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/ESRO-2A_cover-1-672x372.jpg)

![[April 8, 1968] Ups, Downs and Tragedy: An Eventful Month in Space (Gagarin's crash, Zond-4, OGO-5, Apollo-6)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/680408gagarin-672x372.jpg)

![[January 24, 1968] On Track for the Moon (Apollo 5 and Surveyor 7]](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/apollo_5_patch-672x372.jpg)

![[November 12, 1967] Still in the Race! (Apollo-4, Surveyor-6, OSO-4 and Cosmos-186-188)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Apollo-4-672x372.jpg)

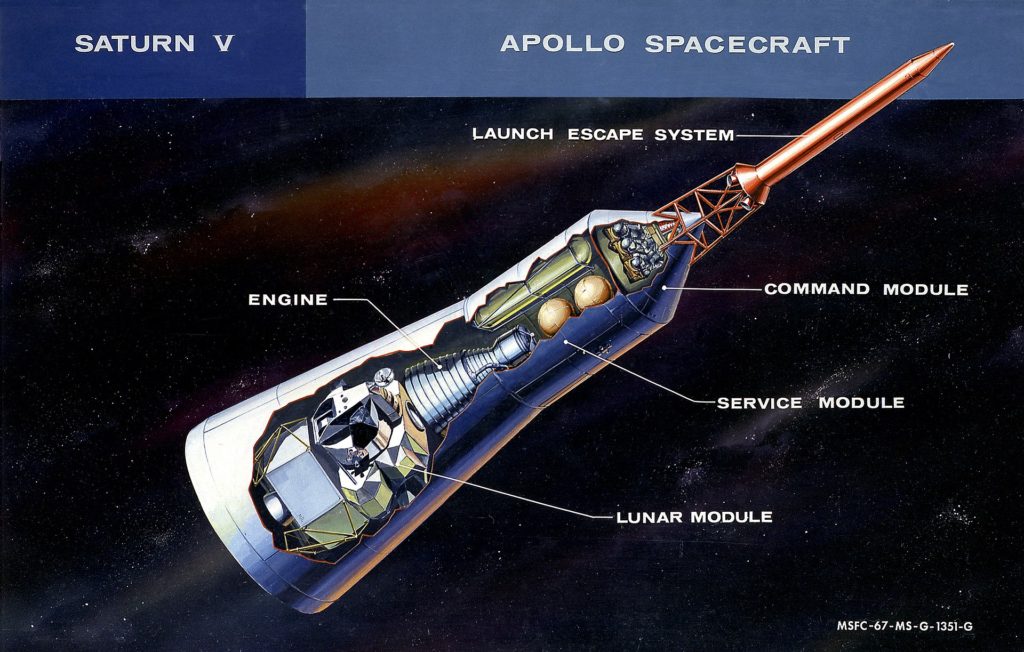

The F-1 rocket motor, five of which power the Saturn V’s S1-C first stage, is the most powerful single combustion chamber liquid-propellant rocket engine so far developed (at least as far as we know, since whatever vehicle the USSR is developing for its lunar program could have even more powerful motors).

The F-1 rocket motor, five of which power the Saturn V’s S1-C first stage, is the most powerful single combustion chamber liquid-propellant rocket engine so far developed (at least as far as we know, since whatever vehicle the USSR is developing for its lunar program could have even more powerful motors).

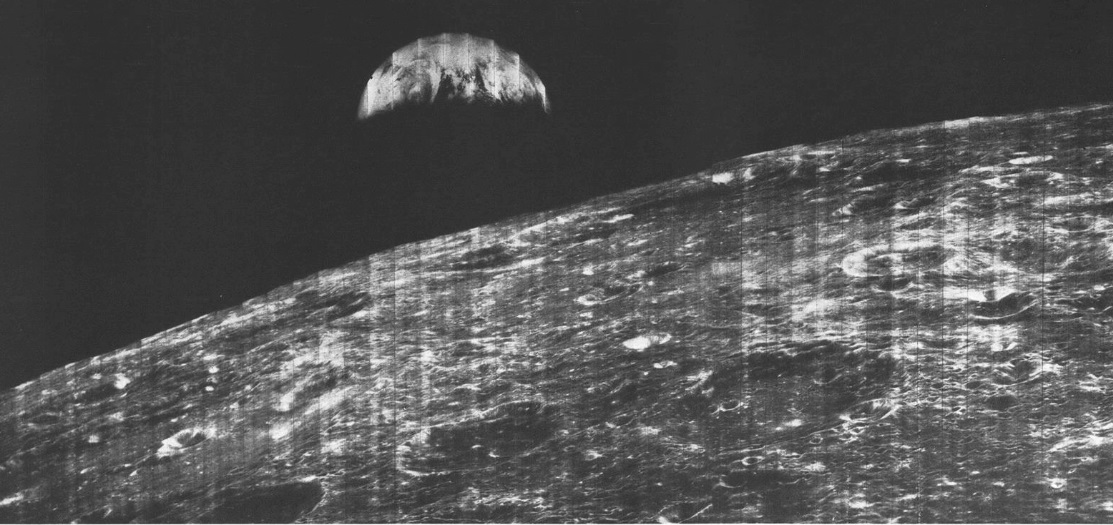

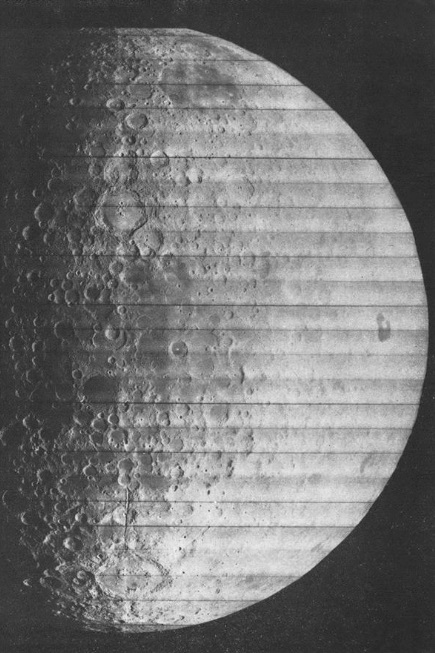

Lunar Orbiter-3 image of the Moon's far side, showing the crater Tsiolkovski

Lunar Orbiter-3 image of the Moon's far side, showing the crater Tsiolkovski

OSO-4 under construction

OSO-4 under construction

![[October 28, 1967] Unveiling Venus – at Least a Little (Venera-4 and Mariner-5)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Venus-desert.png)

![[August 24, 1967] Up and Around (Lunar Orbiter)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670824lunarorbiter-672x372.jpg)

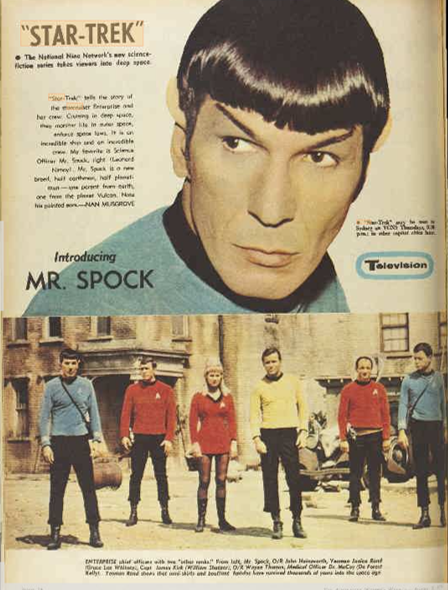

![[August 22, 1967] Boldly Going Down Under (Star Trek, Spies and space in Australia)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/AWW-ST-448x372.png)

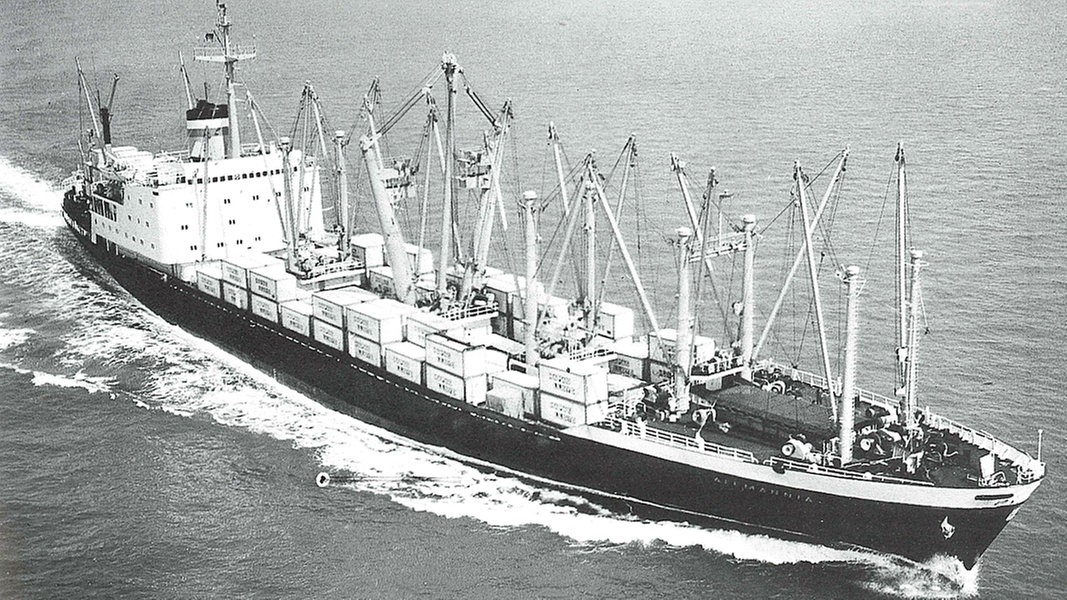

![[August 16, 1967] Boxes, Big Steel Boxes: The Rise of the Shipping Container](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Fairland-im-Uberseehafen_Bremenports-768x594-1-672x372.jpg)

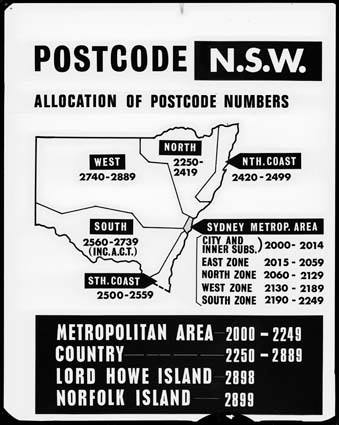

![[July 22, 1967] Getting the mail through (Australia introduces Postcodes)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Postcode-3-423x372.jpg)

![[June 28, 1967] Around the World in Two Seconds (<i>Our World</i> Global Satellite Broadcast)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Our-World-1.png)