by Kaye Dee

The accelerating pace of the US and Soviet space programmes over the past few months has drawn our attention away from space developments in other parts of the world, especially with the excitement of the historic Apollo 8 lunar mission so recently behind us and Apollo 9’s in-orbit test flight (finally!) of the Lunar Module next month. But there have been many developments on the European space scene since I wrote about it in May last year, so I think it’s time for an update!

Triumph: ESRO 1A Finally in Orbit

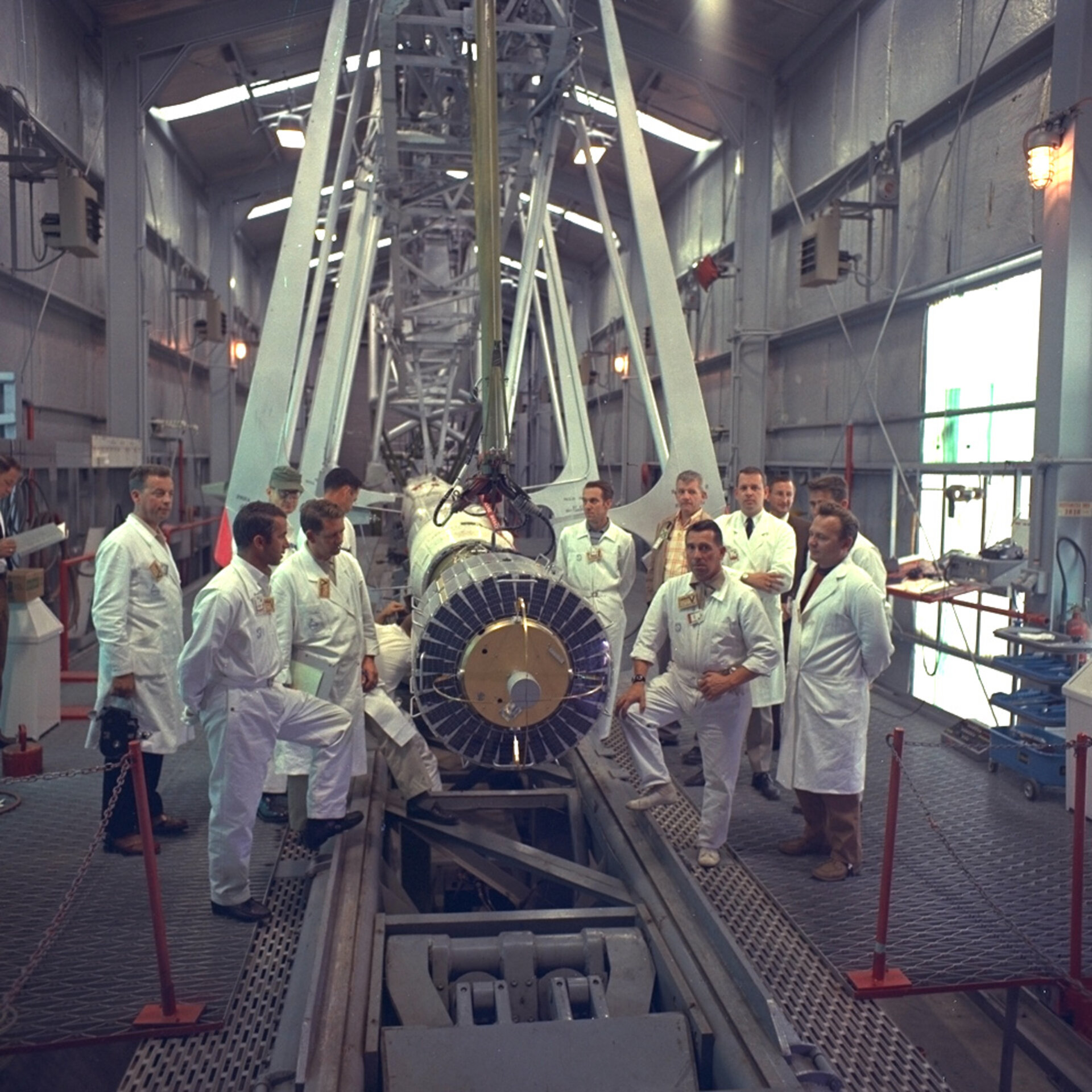

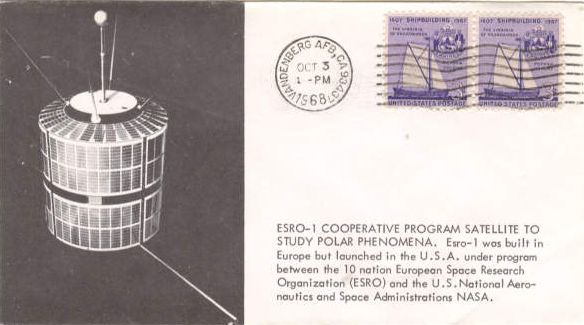

Triumph: ESRO 1A Finally in OrbitMy previous European space report noted that the European Space Research Organisation’s (ESRO) first satellite, ESRO 2B, reached orbit ahead of ESRO 1A, the latter satellite delayed due to difficulties in the development of its instrumentation payload. But ESRO 1A was finally launched on 3 October 1968 from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, using a Scout launch vehicle.

ESRO 1A mounted on its Scout vehicle ahead of its launch at Vandenberg AFB

ESRO 1A mounted on its Scout vehicle ahead of its launch at Vandenberg AFBFired into a 90° polar orbit, with an initial apogee of 930 miles and a perigee of 171 miles, ESRO 1A is designed for a nominal lifetime of six months. However, it is already looking likely that the satellite will survive much longer and possibly still be in orbit when its follow-up twin ESRO 1B is launched later this year (presently planned for some time in October).

The ESRO1 missions were first outlined in 1963 at scientific meetings of COPERS (Commission Préparatoire Européenne de Recherche Spatiale, which is the French name for the European Preparatory Commission for Space Research, a predecessor of ESRO), but the programme has been developed as a joint venture between NASA and ESRO. NASA provided the Scout vehicle for ESRO 1A, although ESRO will purchase the Scout launcher for the ESRO 1B flight.

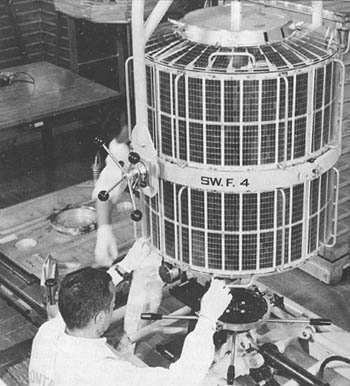

Designed by ESRO, the construction of both ESRO 1 satellites is all-European: Laboratoire Central de Telecommunications (Paris) is the prime contractor, with assistance from Contraves AG (Zurich), and Antwerp-based Bell Telephone Manufacturing Company, with final testing taking place at ESRO’s ESTEC facility. Weighing about 187 pounds, the cylindrical, non-stabilised ESRO 1 satellites are 30 inches in diameter and 36.6 inches tall (specifically designed to fit within the Scout vehicle fairing) and powered by solar-cells.

Designed by ESRO, the construction of both ESRO 1 satellites is all-European: Laboratoire Central de Telecommunications (Paris) is the prime contractor, with assistance from Contraves AG (Zurich), and Antwerp-based Bell Telephone Manufacturing Company, with final testing taking place at ESRO’s ESTEC facility. Weighing about 187 pounds, the cylindrical, non-stabilised ESRO 1 satellites are 30 inches in diameter and 36.6 inches tall (specifically designed to fit within the Scout vehicle fairing) and powered by solar-cells.ESRO 1A (‘Aurora’) and ESRO 1B (‘Boreas’) have been designed to study how the auroral zones respond to geomagnetic and solar activity. Their payloads are directly derived from earlier sounding rocket experiments measuring the radiation characteristics of the upper atmosphere. In orbit, the satellites’ axis of symmetry is magnetically aligned along the Earth's magnetic field. They can make direct measurements as high-energy charged particles from the Sun and deep space plunge from the outer magnetosphere into the atmosphere (ESRO 1B will be placed in a lower orbit that 1A to provide comparative data at different altitudes). The satellites can also investigate the fine structure of the aurora borealis and correlate studies on auroral particles, auroral luminosity, ionospheric composition, and heating effects.

ESRO 1A carries seven scientific experiments chosen to measure a comprehensive range of auroral effects. Identical or similar experiments will be carried on ESRO 1B.

ESRO 1A carries seven scientific experiments chosen to measure a comprehensive range of auroral effects. Identical or similar experiments will be carried on ESRO 1B.Tough Luck: Another ELDO Launch Failure…

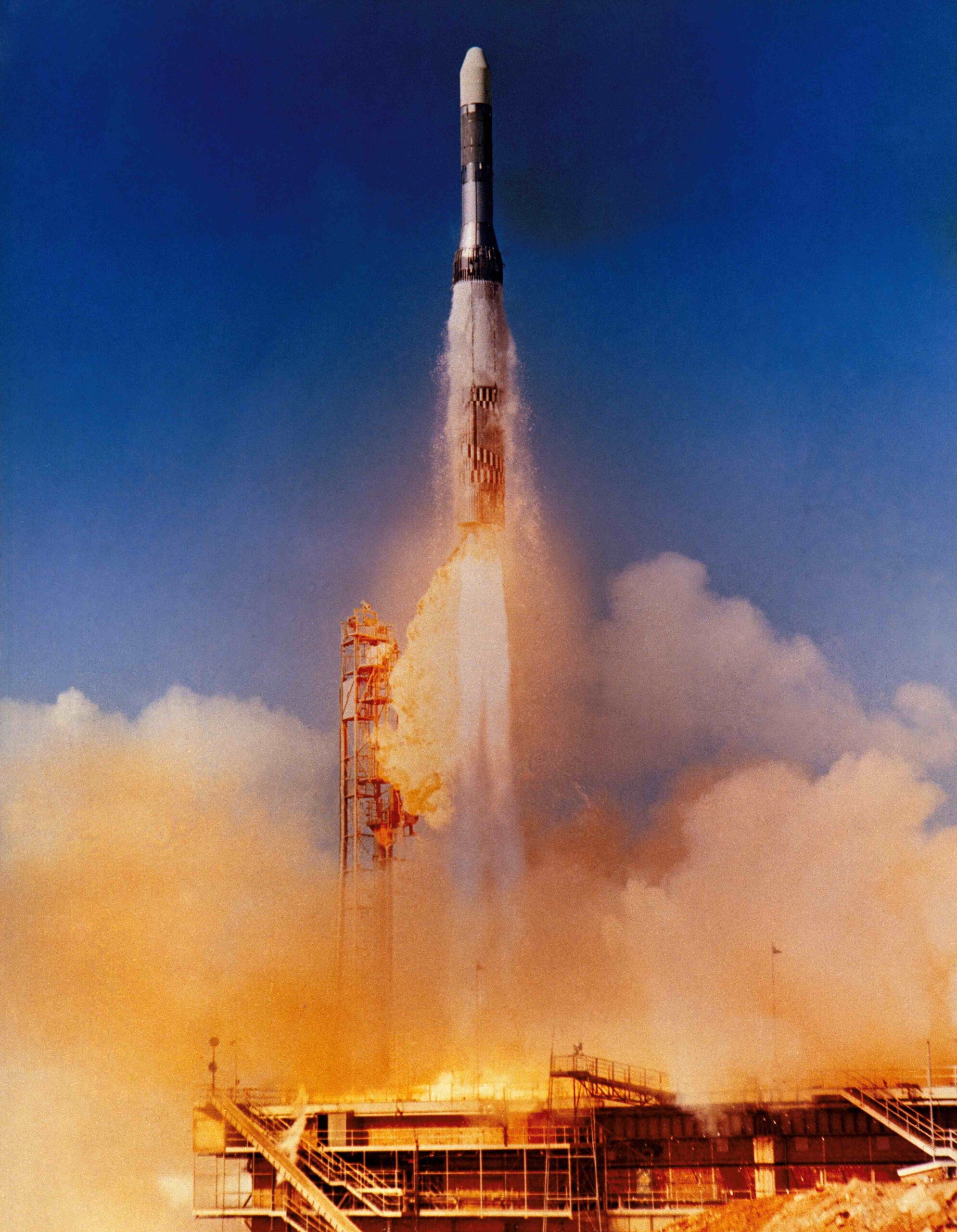

Unfortunately, the European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO) has yet to taste the same success as ESRO, with repeated failures in its Europa satellite launcher test flights, which I've covered in detail in previous articles.

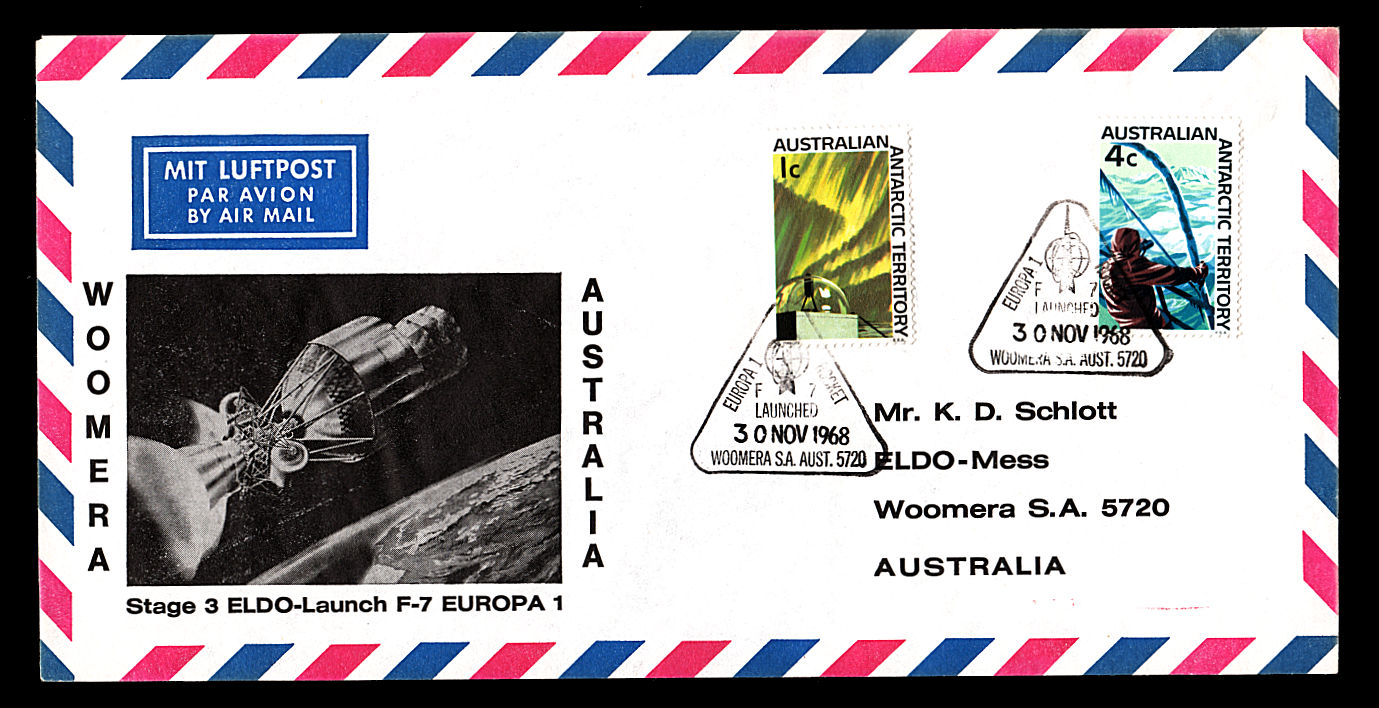

Despite the loss of both Europa F6/1 and F6/2 due to failures of the French ‘Coralie’ second stage, the Europa F7 flight was scheduled for a November launch last year, as the first vehicle to fly with all three of the rocket’s stages active. This eighth firing in the ELDO test programme marked the beginning of Phase 3 of the Europa test flights. It would be the first attempt to launch ELDO’s Italian-built STV (Satellite Test Vehicle) satellite into orbit, as well as the first time that the ELDO down-range guidance and tracking station at Gove in the remote Arnhem Land region of the Northern Territory (primarily developed by Belgium) would actively participate in a Europa launch.

View of the ELDO downrange tracking station, near Gove in the Northern Territory. The area is also known by its Aboriginal name of Nhulunbuy

View of the ELDO downrange tracking station, near Gove in the Northern Territory. The area is also known by its Aboriginal name of NhulunbuyThe failure of the Coralie stage to separate during the F6/2 launch, due to an electrical fault, meant that modifications had to be made to prevent a recurrence of the issue. So there was plenty of tension (and frustration) in the air when last-second delays halted two attempts to launch F7 on 25 November. Both aborts occurred just 35 seconds before the rocket was due to lift off, and were caused by the discovery of a fault in the Coralie staging system between the first and second stages – nobody wanted a repeat of F6/2!

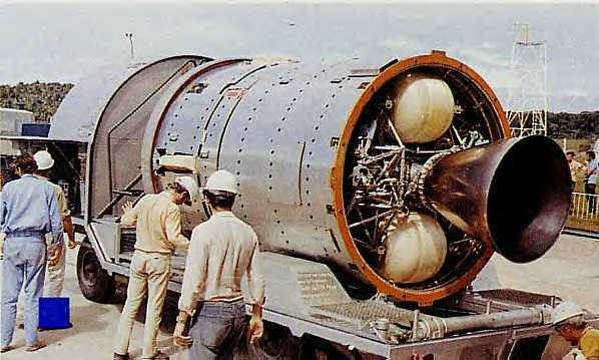

A Coralie second stage engine being checked out at Woomera prior to stacking the Europa vehicle for launch

A Coralie second stage engine being checked out at Woomera prior to stacking the Europa vehicle for launchA launch attempt on 27 November was cancelled due to another fault, as was a fourth attempt on the 28th, which was caused by a faulty indication in a pressure switch system in the engines of the British Blue Streak first stage.

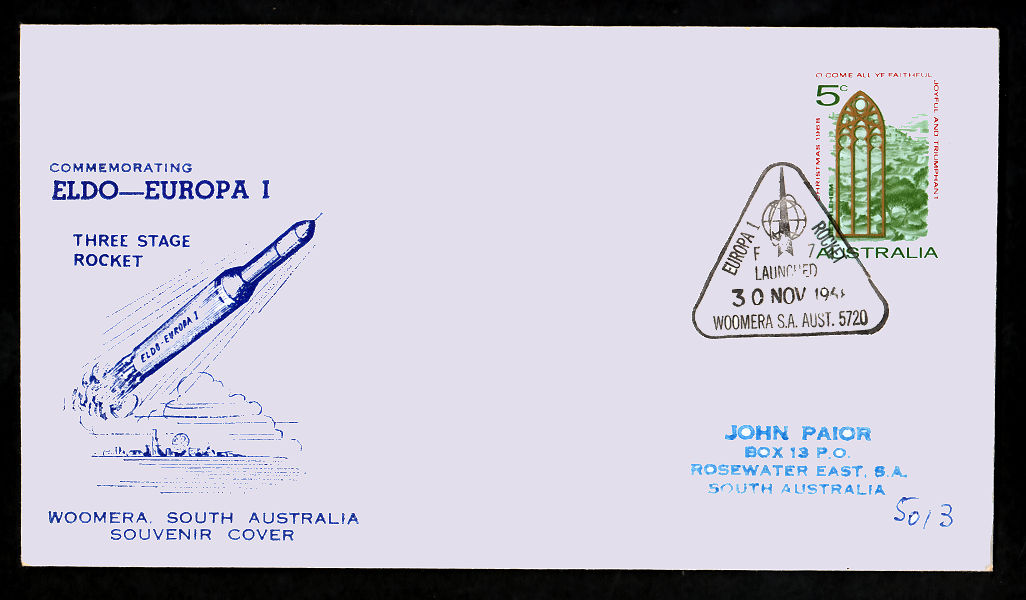

Finally, on the fifth attempt, Europa F7 lifted off on 30 November (Australian time; still 29 November in Europe), but this flight, too, was doomed to be short-lived. The second stage separated and functioned perfectly: this time it was the West German ‘Astris’ third stage that caused the failure.

Finally, on the fifth attempt, Europa F7 lifted off on 30 November (Australian time; still 29 November in Europe), but this flight, too, was doomed to be short-lived. The second stage separated and functioned perfectly: this time it was the West German ‘Astris’ third stage that caused the failure.

The Astris stage separated and ignited as expected but burned for just seven seconds (instead of the planned 300 seconds) before it exploded. Investigations as to the cause of the failure are ongoing, but at present there are three possible causes under consideration: rigid pressurisation pipes that may have fractured; an explosive bolt, part of the WREBUS flight safety destruct system, that may have been inadvertently been triggered by a stray electrical current; or a rupture of the tank diaphragm in the third stage, which separates the fuel and oxidiser. The diaphragm may have been weakened during pre-flight preparations. At present we can only await the outcome of the investigations and hope that they do not delay the launch of Europa F8, currently scheduled for June or July this year.

The Astris stage separated and ignited as expected but burned for just seven seconds (instead of the planned 300 seconds) before it exploded. Investigations as to the cause of the failure are ongoing, but at present there are three possible causes under consideration: rigid pressurisation pipes that may have fractured; an explosive bolt, part of the WREBUS flight safety destruct system, that may have been inadvertently been triggered by a stray electrical current; or a rupture of the tank diaphragm in the third stage, which separates the fuel and oxidiser. The diaphragm may have been weakened during pre-flight preparations. At present we can only await the outcome of the investigations and hope that they do not delay the launch of Europa F8, currently scheduled for June or July this year.…And a Satellite Lost

While it was not the main objective of the F7 flight, it is particularly disappointing that the Italian test satellite did not reach orbit, as it would have become the second satellite launched from Woomera, exactly one year after Australia’s own WRESAT.

The first flight-ready STV satellite being checked out following its arrival at Woomera

The first flight-ready STV satellite being checked out following its arrival at WoomeraThe octagonal prism-shaped STV satellites (successors will be flown on Europa F8 and F9) have been built for ELDO by Fiat Aviazione. The 472 pound satellite carries instruments to characterise the launch environment of the Europa vehicle, providing information on the conditions and stresses that future satellites launched on Europa vehicles will need to be capable of surviving.

Despite the loss of both the rocket and the satellite, ELDO has been referring to Europa F7 as a “successful trial”, as it has enabled its engineers to acquire data about the performance of the Coralie second stage in flight and came close to placing a satellite into orbit. ELDO representatives are saying that, the Europa vehicle has “emerged for the first time as a practical proposition.”

Turmoil: the State of European Space Policy

Last May, I asked whether Britain had lost its way in space, and whether European space plans would flourish or wither, due to changing views on the future direction of Europe’s space activities and reductions in funding. Since then, the outlook has become even more uncertain, with disagreements over juste retour project work allocations and the ELDO budget creating turmoil.

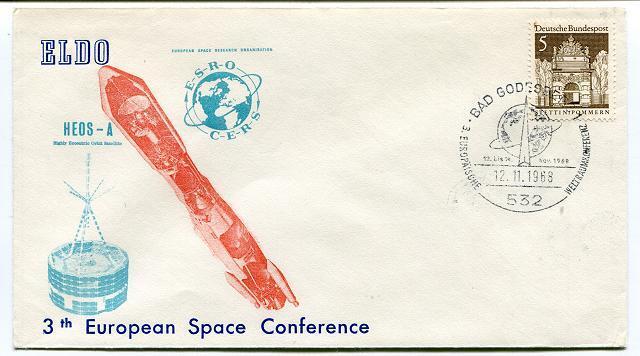

In November last year, Ministers, space organisation representatives and space experts from 16 European countries, as well as Australia and Canada, met for the third European Space Conference, held in Bonn, West Germany. At this meeting, a proposal was put forward to merge ELDO and ESRO to form a pan-European space authority by early 1970, which would be known as the European Space Agency.

This idea proved popular with many of the attending nations, but less so with Britain, which expressed the view that it was unlikely that Europe could launch satellites economically. As noted last year, Britain has already announced its intention to withdraw from ELDO, although it has committed to continue supplying Blue Streak first stages for the Europa II vehicle.

This idea proved popular with many of the attending nations, but less so with Britain, which expressed the view that it was unlikely that Europe could launch satellites economically. As noted last year, Britain has already announced its intention to withdraw from ELDO, although it has committed to continue supplying Blue Streak first stages for the Europa II vehicle. However, the British Government has offered to back a revised European space programme designed to yield “practical results”. Britain wants Europe to concentrate on developing applications satellites for weather forecasting, telecommunications, and scientific research, giving up the development of independent European launchers in favour of using American vehicles.

The British proposal includes an offer to contribute to a project for an “information transfer satellite” to be completed by 1975, providing a point-to-point television relay service between London and Paris for the European Broadcasting Union. In addition, Britain would participate in a long-term applied research programme to improve European industrial space capability, in conjunction with funding an immediate economic study of the market for applications satellites. The quid-pro-quo for British support for this ambitious “practical space programme” is that the UK must be released from its present financial commitment to ELDO. This is certainly ironic, given that Britain was the driving force behind the original creation of ELDO!

The British proposal includes an offer to contribute to a project for an “information transfer satellite” to be completed by 1975, providing a point-to-point television relay service between London and Paris for the European Broadcasting Union. In addition, Britain would participate in a long-term applied research programme to improve European industrial space capability, in conjunction with funding an immediate economic study of the market for applications satellites. The quid-pro-quo for British support for this ambitious “practical space programme” is that the UK must be released from its present financial commitment to ELDO. This is certainly ironic, given that Britain was the driving force behind the original creation of ELDO!ELDO's Budget Crisis

After the failure of Europa F7, the ELDO Council met on 19-20 December to vote on the organisation’s 1969 budget, with Britain again the fly in the ointment, declaring that it would not support the new “austerity plan” compromise budget proposed by West Germany to cover the final two years of the Europa-1 development programme.

Using a loophole in the ELDO Convention to characterise the German proposal as a “further programme” (ie: it was not part of the original ELDO programme that it had signed up to), Britain declared that it had “no interest” in the plan and so was not obliged to contribute to it financially. It would only support the 1969 budget if its outstanding contribution to ELDO was reduced to £10 million for the years 1969, 1970 and 1971.

Using a loophole in the ELDO Convention to characterise the German proposal as a “further programme” (ie: it was not part of the original ELDO programme that it had signed up to), Britain declared that it had “no interest” in the plan and so was not obliged to contribute to it financially. It would only support the 1969 budget if its outstanding contribution to ELDO was reduced to £10 million for the years 1969, 1970 and 1971. Italy took a similar line, supporting the British view and declaring itself “not interested”, and would not vote for the 1969 budget. In addition, Italy formally rejected as inadequate an offer to become the prime contractor of the apogee motor in the Symphonie communications satellite programme.

This recalcitrance on the part of Britain and Italy has plunged ELDO into a budget crisis, and the organisation has been operating on a contingency funding basis since 31 December. Practical considerations, and the terms of the ELDO Convention, indicate that the impasse needs to be resolved within three months, at which point a budget must be approved or the original treaty becomes invalid.

An excerpt from the journal Nature, reporting on ELDO's budget crisis

An excerpt from the journal Nature, reporting on ELDO's budget crisisA meeting of the relevant Ministers from all seven ELDO member states is currently scheduled for 26 February to seek a political solution to the problem and find a way forward for Europe’s space ambitions before they fragment. What’s that Chinese proverb? “May you live in interesting times”!

An Australian Postscript: No WRESAT-2

In my article on the launch of Australia’s first satellite at the end of November 1967, I mentioned that the Weapons Research Establishment was planning to put a proposal to the Australian Government for the establishment of an Australian space programme, managed by the WRE. This proposal went to the Cabinet for consideration last year, but was rejected by the Government on the basis of cost, despite the modest budget it was proposing. This is not the first proposal for an Australian space programme that has been rejected by Cabinet, which seems to have little appetite for funding Australian civil space projects. To the frustration of all those involved, it looks like WRESAT-1 will not, after all, be followed by WRESAT-2.

Signing off

Well, in the vernacular of your beloved Walter Cronkite, "That's the way it is." I'm sorry I haven't happier news to report just yet, but you'll hear it here first when I have it!

(And my thanks to my Uncle Ernie, the philatelic collector, for providing the selection of space covers (envelopes) that I have used to illustrate this article.)

![[February 16, 1969] Triumph, Tough Luck and Turmoil (European Space Update)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ESRO-1A_cover-1-672x372.jpg)

![[June 6, 1964] Going Up from Down Under (The launch of the Blue Streak rocket)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640606Blue-Streak-launch-672x372.jpg)