Are you finding us from Worldcon?

Join us in Portal 55 (a great deal of DISCORD there…) for weekly broadcasts and perennial discussion!

by Kaye Dee

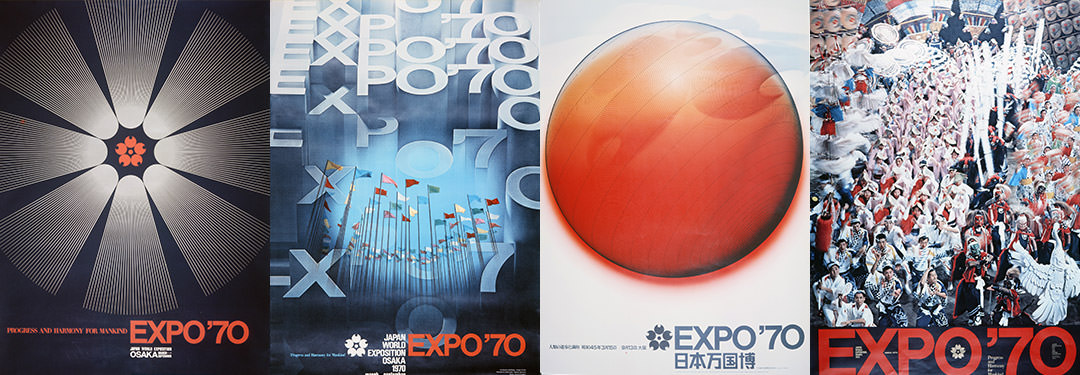

I’ve recently returned from a trip I never thought I’d get the chance to take – a whirlwind visit to Expo 70 in Osaka, Japan, courtesy of an Australian Academy of Science study tour. As an experience, Expo 70 was such a stunning kaleidoscope of colours and cultures, architecture, artworks and technology that I’m still reeling from all the impressions it left on me!

Welcome to the World of Tomorrow?

Since the 1939 New York World’s Fair, with its “Building the World of Tomorrow” theme and famous “Futurama” exhibition, 20th Century international expositions have helped to imbue Western popular culture with the belief that an amazing technology-enhanced science fiction future lies somewhere just beyond the much-hyped horizon of the Year 2000 – a future filled with superfast trains, flying cars, all kinds of labour-saving household devices, exotic leisure activities and gravity-defying architecture.

Since I never made it to any of the previous post-War world’s fairs – Brussels in 1958, with its Atomium; the 1962 21st Century Exposition in Seattle; the 1964 New York World’s Fair, which offered us “Futurama II”, and Expo 67 in Montreal (the first to be designed to take advantage of global satellite communications via INTELSAT) – I was savouring the opportunity to finally have my own first-hand visit to a world of tomorrow, and one with a Japanese twist. After all, just to get there, I had to take a train from Tokyo that feels like a slice of science fiction itself – the incredible Shinkansen, or bullet train!

So, with the memories of my literally flying visit to Japan to spend three days at Expo 70 fresh in my mind, let me take you on a Journey to the latest world's fair to see if the future unfolds.

How the Futurama II diorama at the 1964 New York World's Fair envisaged a city in the year 2014

How the Futurama II diorama at the 1964 New York World's Fair envisaged a city in the year 2014

Continue reading [August 24, 1970] Have I Seen the Future? (Expo 70, Osaka, Japan)

![[August 24, 1970] Have I Seen the Future? (Expo 70, Osaka, Japan)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/EXPO70-logo-2-672x372.png)

![[July 31, 1970] Not so Brillo… (August 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700731analogcover-672x372.jpg)

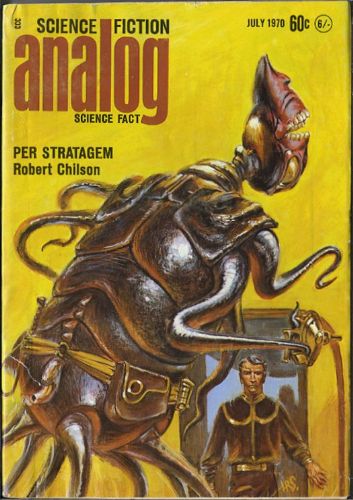

![[June 30, 1970] Star light… per stratagem (July 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700630analogcover-353x372.jpg)

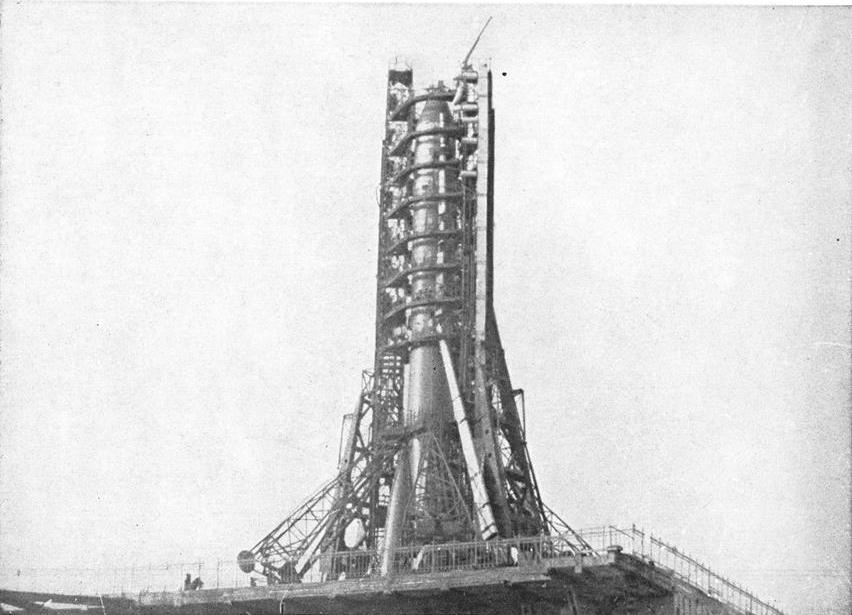

![[June 20, 1970] Gemini Too (the two-week flight of <i>Soyuz 9</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700620launch-443x372.jpg)

![[May 31, 1970] A Compulsion to read (June 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/700531analogcover-672x372.jpg)

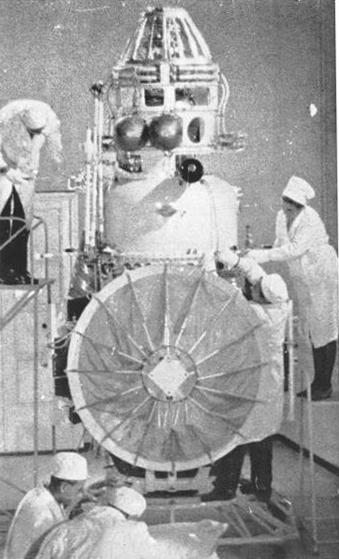

![[April 26, 1970] Red stars in space (Communist China and the USSR make leaps)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700426dongfanghong1-672x372.jpg)

![[April 22, 1970] “Houston, We’ve had a Problem Here!” (Apollo-13 emergency in space)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Apollo-13-13-672x372.jpg)

![[March 30, 1970] The Age of Explorer — the end of the Space Race](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700331nixon-672x372.jpg)