by Victoria Silverwolf

Modes of Transportation

I hope that the Cunard Line will forgive me for stealing their famous slogan. By the way, isn't this a lovely advertisement?

In this modern world, there are all kinds of ways of getting around. There are luxury liners, as shown above. There are airplanes, complete with friendly attendants to cater to your every whim.

This ad is about ten years old. It must have come from a magazine in a doctor's waiting room.

There are, of course, automobiles, that you can either own or rent when you need them.

I do not, however, recommend jumping directly from a plane to a car.

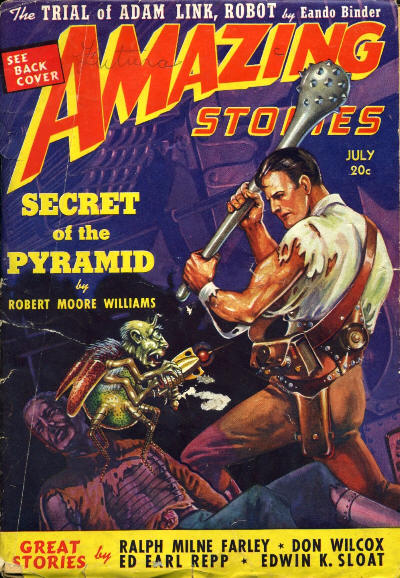

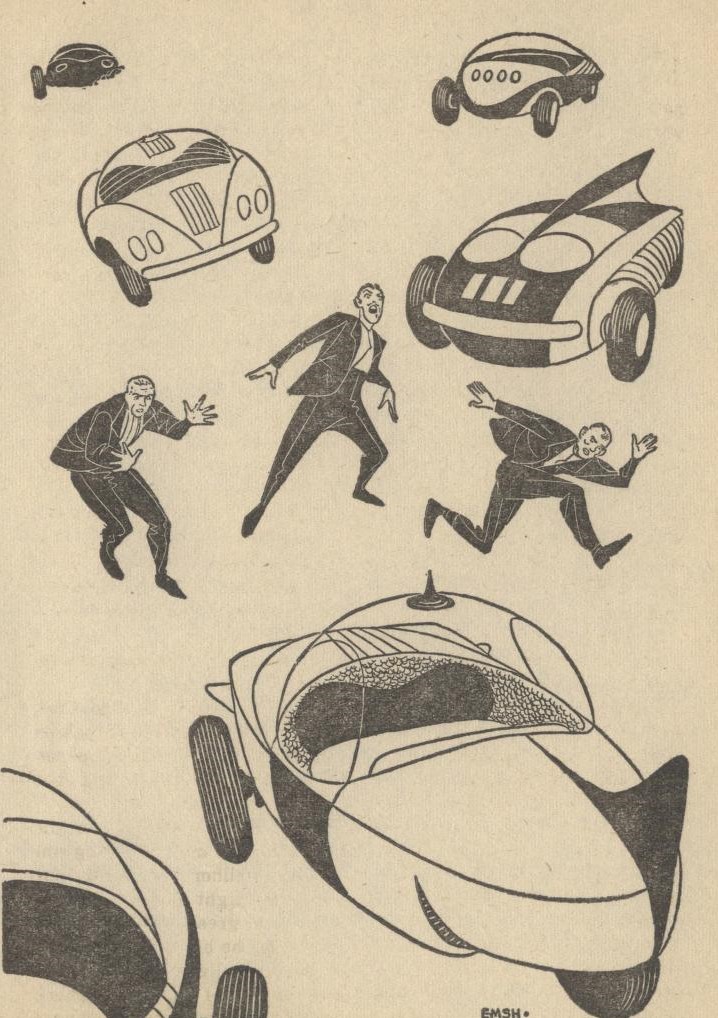

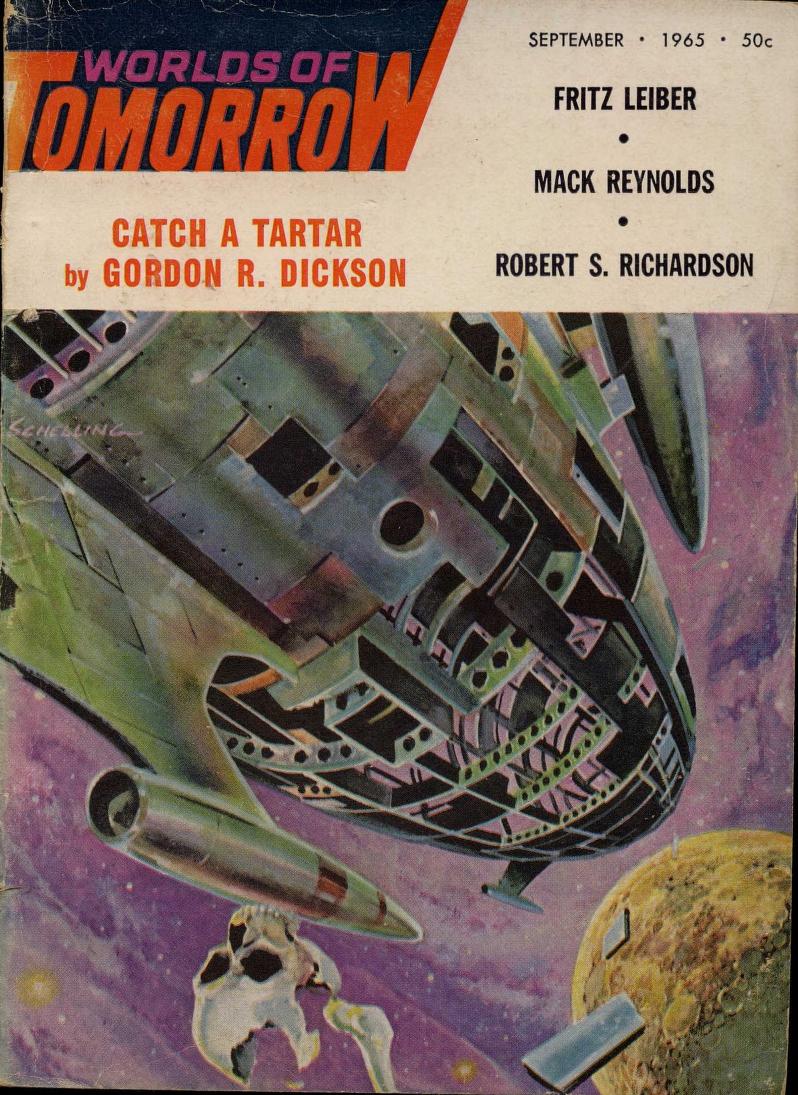

In science fiction, we have lots of futuristic devices to send us from one place to another, from moving sidewalks to starships. The latest issue of Worlds of Tomorrow features people transported through space and time in various ways. The lead novella includes a method of getting from Point A to Point B that I haven't seen before, and that I don't think I would enjoy.

Dying To Be Somewhere Else

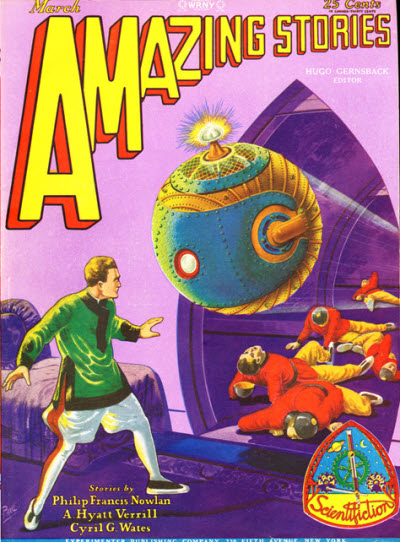

Cover art by Gray Morrow.

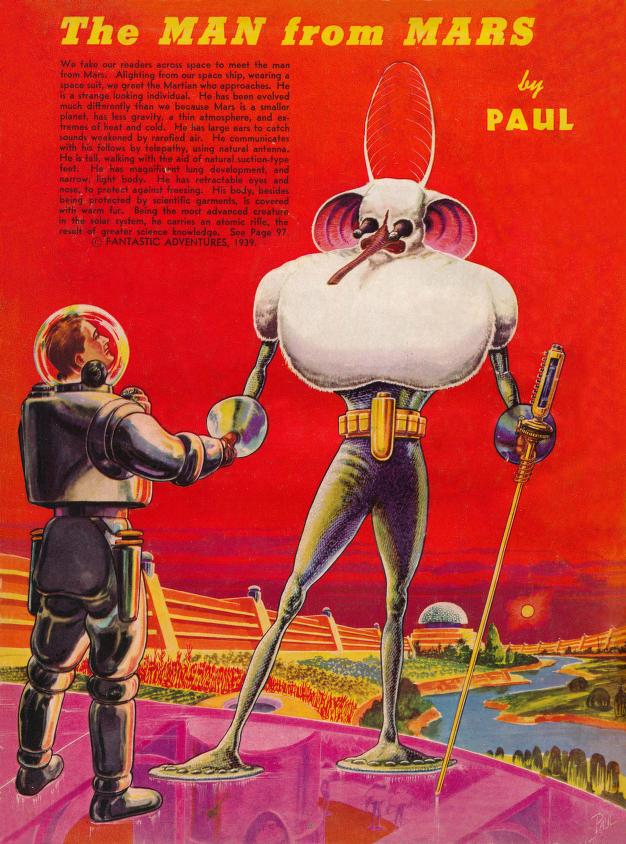

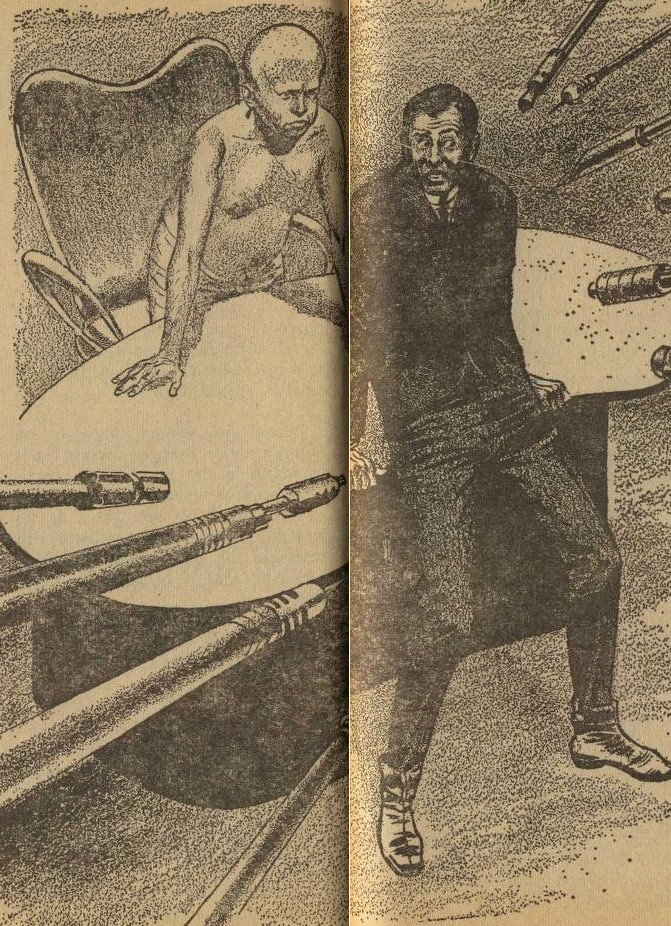

The Suicide Express, by Philip Jose Farmer

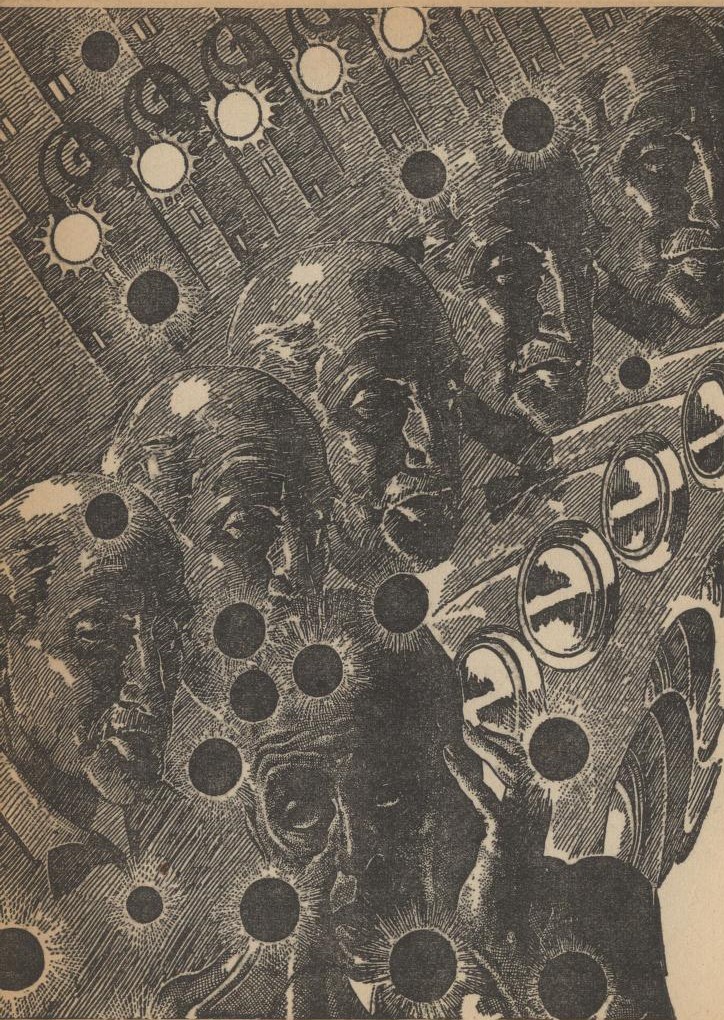

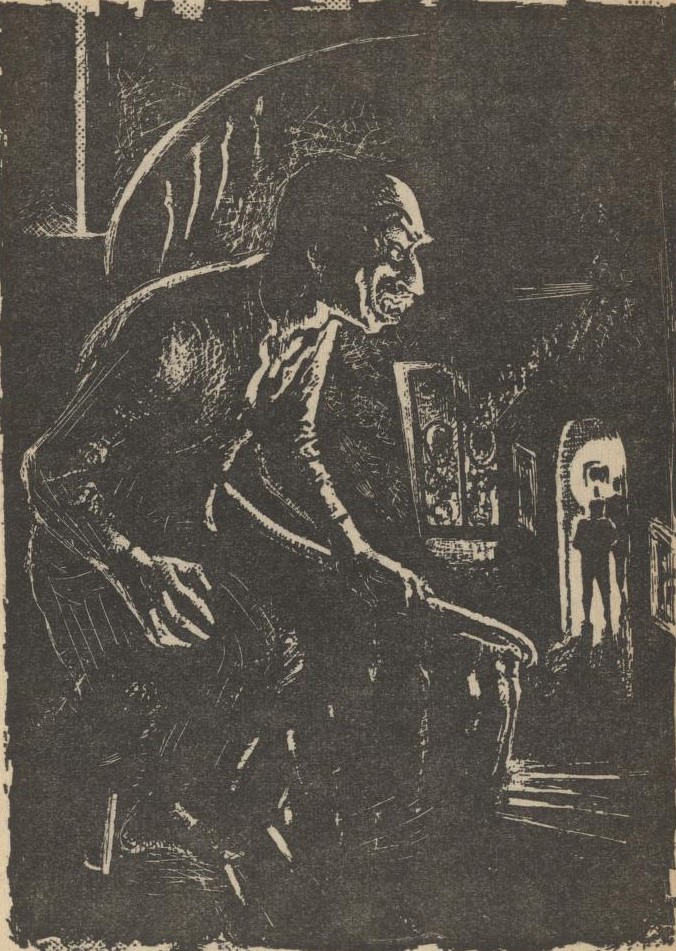

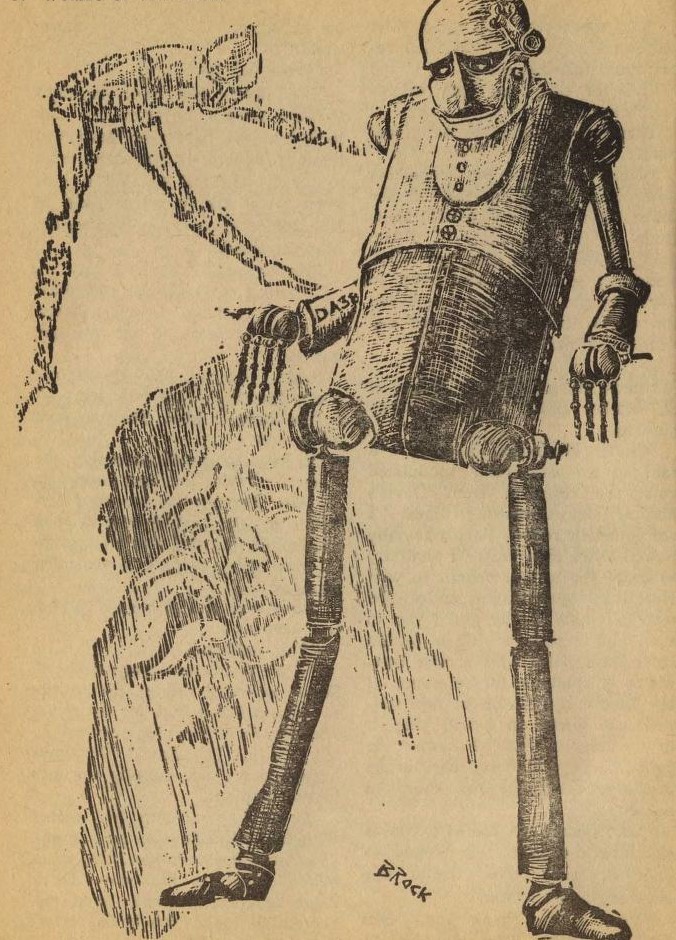

Illustrations by Jack Gaughan.

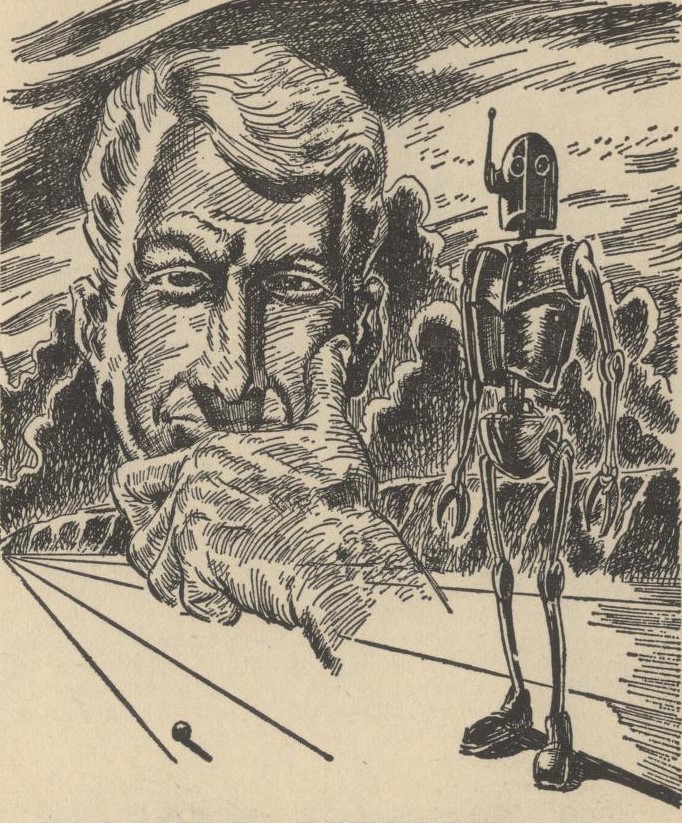

We return to the planet known as Riverworld, where everyone who has ever lived on Earth is reincarnated into a young and healthy body. Our hero is, once more, the Nineteenth Century adventurer Richard Francis Burton. It turns out that anyone who dies on Riverworld is reincarnated again, but in a different location on the giant planet.

Burton discovers that his old nemesis, the infamous Nazi leader Hermann Goering, has been reincarnated in the same place he now resides, after Burton killed him. We'll find out later that the two enemies come back to life in identical locations more than once. There is some kind of bond between them, it seems, although why remains a mystery.

The enormous river that gives this world its name runs from the north pole, all the way around the planet, then back to where it started. That doesn't make geographic sense, of course, so it's clear that some kind of super-advanced technology is involved. There are tales of a bold explorer who spotted a vast tower at the head of the river, beyond impassible mountains. Determined to unlock the secrets of Riverworld, Burton sets out to find the tower. Because sailing all the way to the north pole, if it is even possible, would take many decades, he uses another method of travel.

He kills himself. Seven hundred and seventy-seven times, to be exact. The odds are low that he'll be reincarnated near the north pole, but he's willing to take the chance.

Meanwhile, the so-called Ethicals who created Riverworld are hunting down Burton, apparently because he seems to be the only person who was conscious, in some kind of storage area, before being reincarnated. There's also a rogue Ethical, working against the others, who claims to be protecting Burton.

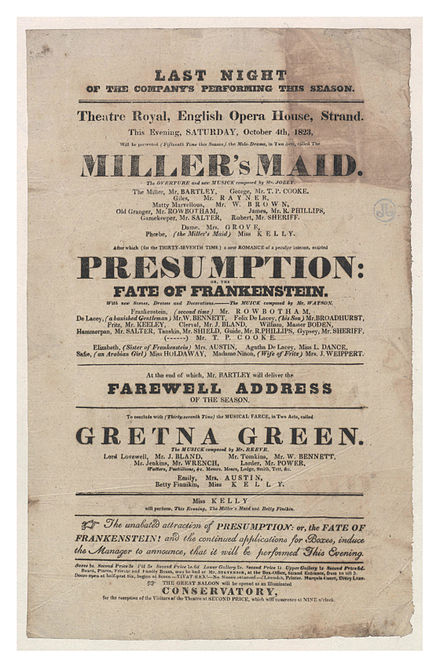

Along the way we meet John Collop, a Seventeenth Century poet. Like Burton and Goering, this is a real historical figure, if not quite as famous. In Farmer's tale, he's a saintly fellow, who is an evangelist for a new religion, the Church of the Second Chance. We also witness the transformation of the guilt-ridden, drug-addicted Goering into what possibly might be a better human being.

Burton meets the Ethicals.

The plot moves swiftly, and there's always something interesting going on. Farmer has latched on to a premise that allows him a lot of room to bring in folks from all sorts of places, from the prehistoric past to the near future. My only quibble is that he raises more questions than he answers. I assume there will be more stories in this series. They might clear things up.

Four stars.

The Kindly Invasion, by Christopher Anvil

Let's see; a story by Christopher Anvil. Do I even have to read it to find out that it's about clever humans outwitting technologically superior but foolish aliens?

In this variation on his favorite theme, the extraterrestrials come to Earth bearing gifts. Among other blessings, they offer a serum that prevents aging. They communicate with humans via telepathy.

Our main character smells something fishy. He assumes the telepathy is really brainwashing. He's the big boss of an arms company, and he decides to sell an excellent firearm to the public dirt cheap, so that lots of people will buy them. (Can you see where this is going?)

Sure enough, the aliens turn out to be bad guys, and the heavily armed folks who didn't fall for their propaganda are ready to take them on.

I was really, really hoping that the arms dealer's suspicions would turn out to be unjustified. Instead, there is nothing at all surprising about the plot. This yarn would have found a more appropriate home in the pages of Analog.

Two stars.

The Super-Sleuths of Science Fiction, by Sam Moskowitz

In the previous issue, we had the first part of a look at crimefighters in SF. This section is exactly like the other. We get a long list of science fiction detective stories, most of which sound really lousy. At the end we get a quick look at modern examples, such as Asimov's robot novels.

My opinion has not changed. I admire the author's scholarship, but the resulting article is as dry as dust.

Two stars.

Like Any World of Gree, by C. C. MacApp

Illustrations by Peter Lutjens.

A bunch of stories about a resourceful hero fighting the slaveholding minions of Gree have already appeared in If. I'm not sure why this one appeared in its sister magazine, but maybe editor Frederik Pohl ran out of room for it.

Anyway, in this adventure we're on Earth. The home world is already occupied by the villains, but the good guys are coming to the rescue. There's just one big problem. Once the followers of Gree are defeated in a space battle, they'll wipe out all life on the planet. Our hero has to sneak in, disguise himself as a human bounty hunter working for the bad guys, work with the local resistance underground, and, as usual, sneak his way into the enemy compound.

Take that, Gree-loving scum!

The series as a whole has been a little repetitious. This one has the novelty of being set on Earth, but otherwise it's the same old espionage and sabotage plot we've seen before.

Two stars.

Umpty, by Basil Wells

A couple of hundred years from now, most folks are unemployed. Some of them eke out a living with subsistence farming, other are outlaws. The protagonist, a fellow hoping to get a job, rescues a woman from a gang of hoodlums. She claims to be from the past, with her mind transported into a body of the future. After some adventures, they find out what's really going on.

There really isn't much to this story other than the twist ending, which I thought was kind of silly. I suppose the background is mildly interesting, but that's about it.

Two stars.

Comets Via the VJSEH, by Robert S. Richardson

The author speculates about the origin of comets having orbits associated with Jupiter. He dismisses the idea that they were captured by the gravity of the giant planet, because there are far too many of them still around, considering their relatively short lifetimes. Did they emerge from Jupiter? No, because they could not possibly escape the immense gravitational pull. Instead, he promotes the hypothesis that they were ejected from Jovian moons, due to volcanic activity.

It seems to me that the argument falls apart if you accept the possibility that there's a steady supply of comets coming from deep in space, maybe beyond Pluto. In that case, there would be plenty of them for Jupiter to grab. The article also has some illustrations that are not reproduced very well, so I haven't bothered to photocopy them here.

Two stars.

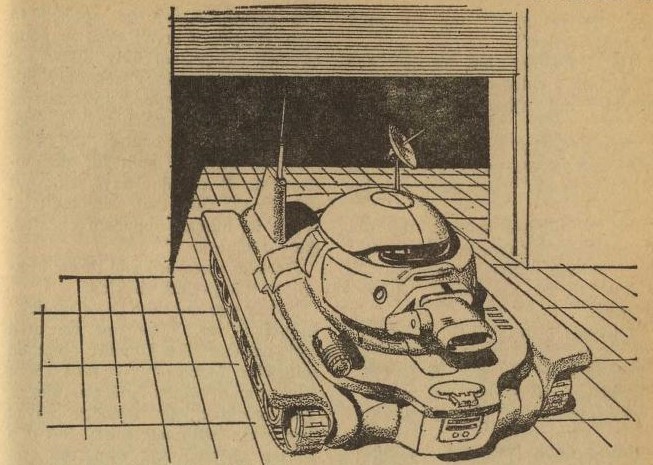

Choice of Weapons, by Richard C. Meredith

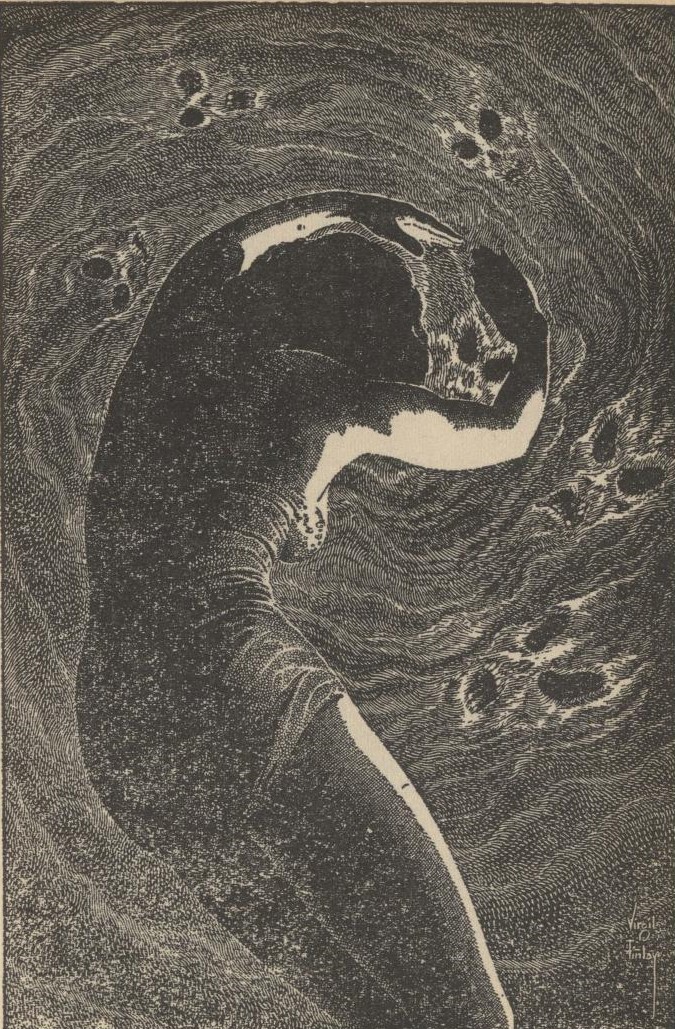

Illustration by Gray Morrow

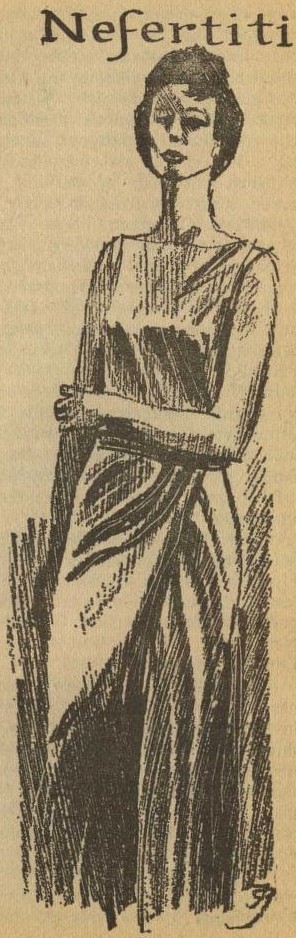

A motley collection of folks gets transported from all kinds of places on Earth, and from different times, in this yarn. There's the hero, an American (I presume) hunter of the present; there's a naked, seemingly comatose little girl; a royal woman of ancient Egypt; a huge fellow of prehistoric times; a woman from a decadent future; an ancient Roman soldier; an Asian woman who might be from just about any time; and a soldier from a brutal future dictatorship.

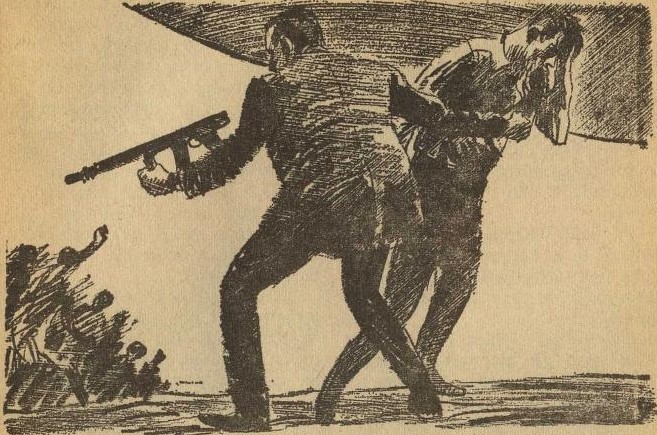

These very confused people find themselves in a metal room. Food appears from time to time, but the amount keeps shrinking. Given this threat to their existence, not to mention conflict over the affections of the sexually provocative woman from the future, it's not a big surprise when violence breaks out. (I forgot to mention that the hunter has his gun, the Roman has his sword, and the man from the future has his laser. The prehistoric man just has his body, which is enough of a weapon.)

There's an explanation for their situation, of course. It also turns out that the little girl, who does not respond to anything at all in any way until the end of the story, is the key to saving the lives of those who survive the ordeal.

I have very mixed feelings about this tale. The frequent killing, along with implied rape, make it disturbing to read. On the other hand, the way in which the author portrays characters from many different times and cultures is convincing. In particular, the half-intelligible language spoken by the woman from the future is fascinating.

Three stars.

Did You Have A Nice Trip?

The good ship Worlds of Tomorrow, under the command of Captain Frederik Pohl, set sail with streamers flying. Her first port of call was well worth the price of boarding. The rest of the voyage, maybe not. As we disembark, we may wistfully wonder if the excursion was really a vital one.

If it's a Galactic Journey, I have to say Yes!

![[January 16, 1966] Getting There Is Half The Fun (March 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n06_1966-03_Anon.Malefactor_0000-3.jpg)

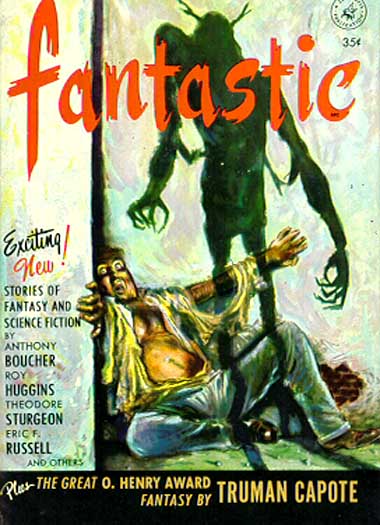

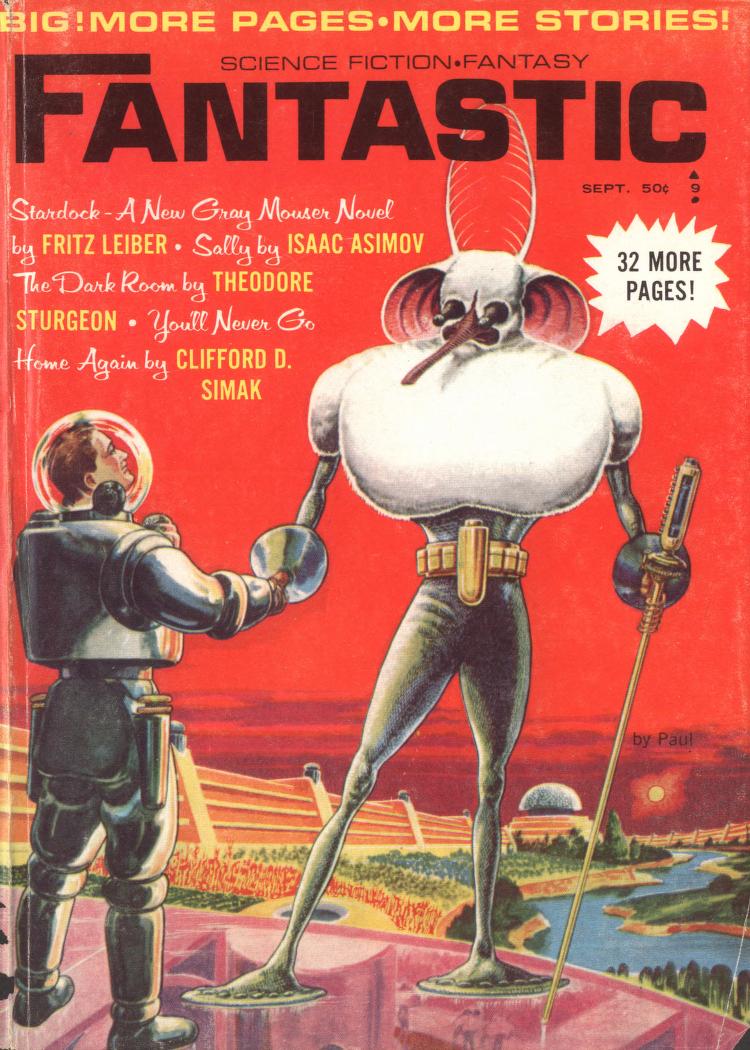

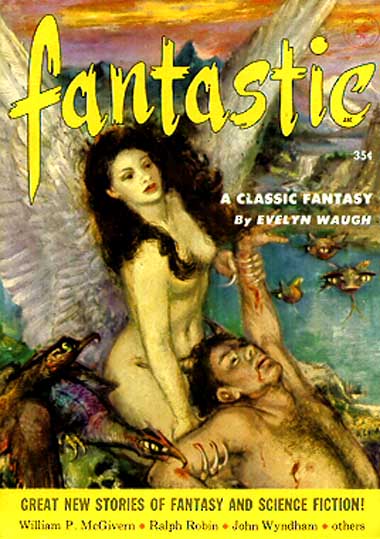

![[December 14, 1965] Expect the Unexpected (January 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Fantastic_v15n03_1966-01_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

![[November 16, 1965] Crime and Punishment (January 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n05_1966-01_dtsg0318.Anon_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

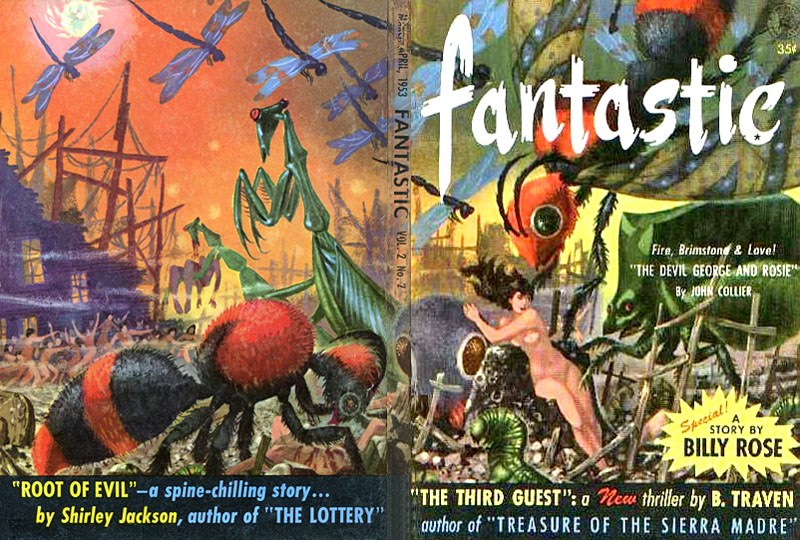

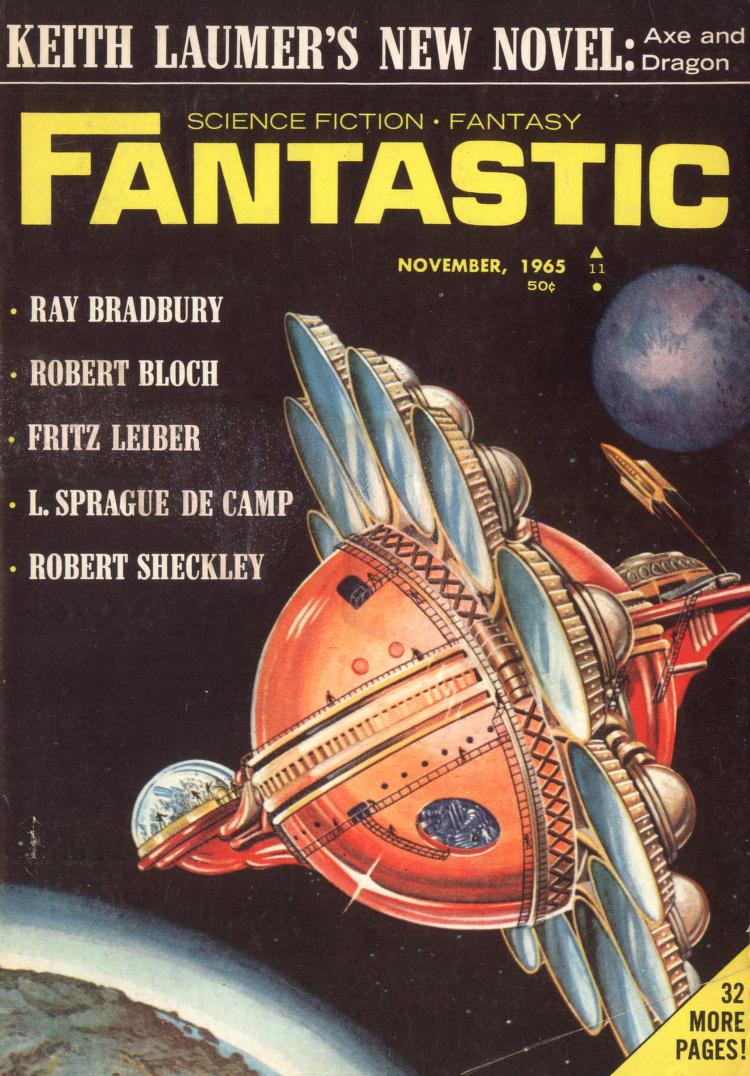

![[October 22, 1965] Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow (November 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Fantastic_v15n02_1965-11_Lenny_Silv3r_0000-2-672x247.jpg)

![[September 24, 1965] False Advertising (<i>Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster</i> and a brief history of Mary Shelley's creation on film)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/4d6e7604f0053e87ac44cfd4c8fb9dd0e9de58b6r1-749-920v2_hq-2-672x361.jpg)

![[September 16, 1965] Blessed Are The Peacemakers (November 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n04_1965-11_0000-2-395x372.jpg)

![[August 10, 1965] Binary Arithmetic (September 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Fantastic_v15n01_1965-09_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[July 24, 1965] Sun, Sand, Surf, Swimsuits, And The Supernatural (<i>How To Stuff A Wild Bikini</i> and a Brief History of Beach Movies)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/1303731403-How-to-Stuff-Wild-Bikini-Movie-1965_hires-672x372.jpg)

![[July 18, 1965] The Prodigal Returneth (September 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n03_1965-09_0000-2-672x293.jpg)

![[May 22, 1965] Goodbye and Hello (June 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Fantastic_v14n06_1965-06_0000-2-672x265.jpg)