by Gideon Marcus

There are many outlets that cover new releases in science fiction and fantasy. But to my knowledge, only one attempts to review every English language publication in the world (not to mention stuff published beyond the U.S. and U.K.!) We are proud of the coverage we provide.

And this is the time of year when the bounty is tallied. From all the books, magazines, comic strips, movies, tv shows, we separate the wheat from the chaff, and then sift again until only the very best is left.

These, then, are the Galactic Stars for 1966!

We have tried to keep the winners to a manageable three winners, but as you'll see, the honorable mentions rather got away from themselves. That's because there was simply more fiction produced this year, what with the three British mags and all. This is a fine problem to have, too much good stuff.

Results are in order of voting for the winners, alphabetical order by author for the honorable mentions.

——

Best Poetry

——

Poetry is always an underrepresented field within SF. Rather than declare a winner in this category, we simply present the four pieces we liked the most this year.

The Gods, by L. Sprague de Camp

Memo to Secretary, by Pat de Graw

The Last Song Sung in Lorien, by Robert Foster

The Case, by Peter Redgrove

——

Best Vignettes (1-8 pages)

——

Day Million, by Frederik Pohl

Some writers take no chances when predicting the future. Pohl is not among them…

Love Is an Imaginary Number, by Roger Zelazny

A modern spin on the Prometheus legend.

Breakaway House, by Ron Goulart

A Max Kearney, occult detective, story. Genuinely funny.

ㅤ

Honorable Mention:

The Plot Sickens, by Brian W. Aldiss

You and Me and the Continuum, by J. G. Ballard

The Plot is the Thing, by Robert Bloch

But Soft, What Light … , by Carol Emshwiller

Mute Milton, by Harry Harrison

Mr. Wilde's Second Chance, by Joanna Russ

—

We had more vignettes to choose from this year, with the result that more made the list. Their content ranged from frivolous fantasy to deadly serious social commentary. It's always impressive when an author can say a lot with a little.

——

Best Short Stories (9-19 pages)

——

The Squirrel Cage, by Thomas M. Disch

Why is the man trapped in a room with only a typewriter and the newspaper for company?

ㅤ

Honorable Mention

No other story got more than one vote by a Journeyer, though virtually all got at least four stars. So, instead of providing summaries or attempting ranks, the following will be listed by recommender.

By John Boston:

When I Was Miss Dow, by Sonya Dorman

At the Core, by Larry Niven

The Roaches, by Thomas M. Disch

By Cora Bulhert:

The Bells of Shoredan, by Roger Zelazny

High Treason, by Poul Anderson

Splice of Life, by Sonya Dorman

By David Levinson:

The Face of the Deep, by Fred Saberhagen

Halfway House, by Robert Silverberg

By Gideon Marcus:

Come Lady Death , by Peter S. Beagle

A Code for Sam, by Lester del Rey

Contact Man, by Harry Harrison

By Kris Vyas-Myall:

The Great Clock , by Langdon Jones

The Loolies Are Here, short story by Allison Rice

By Victoria Silverwolf:

Stars, Won't You Hide Me?, by Ben Bova

Light of Other Days, by Bob Shaw

The Worlds That Were, by Keith Roberts

——

Best Novelettes (20-40 pages)

——

Riverworld, by Philip José Farmer

All of humanity is ressurrected on the banks of the world-river. Including Tom Mix and a certain carpenter from Nazareth…

For a Breath I Tarry, by Roger Zelazny

Two computer brains endeavor to know long-dead humanity. Beautiful. Powerful.

ㅤ

A Two-Timer, by David I. Masson

A 17th Century scholar sojourns for a time in Our Modern Times. Delightful.

Angels Unawares, by Zenna Henderson

An early tale of The People. Kin can be adopted as well as born.

ㅤ

Honorable Mention

An Ornament to His Profession, by Charles L. Harness

Pavane: Lords & Ladies, by Keith Roberts

The Disinherited, by Poul Anderson

The Keys to December, by Roger Zelazny

Defence Mechanism, by Vincent King

Wings of a Bat, by Paul Ash (Pauline Ashwell)

The Eyes of the Blind King, by Brian W. Aldiss

Be Merry, by Algis Budrys

We Can Remember It for You Wholesale, by Philip K. Dick

The Phoenix and the Mirror, by Avram Davidson

——

Best Novella (40+ pages)

——

Behold the Man, by Michael Moorcock

If Jesus did not exist, it would be necessary for a time traveler to go back and invent him…

The Manor of Roses, by Thomas Burnett Swann

A lordlet and his peasant blood brother encounter Mandrakes on the way to the Crusades.

ㅤ

The Last Castle , by Jack Vance

All the bastions of humanity have fallen to the aliens save one. Vance at his most lyrical.

Pavane: Corfe Gate, by Keith Roberts

In an England that remained Catholic, Lady Eleanor leads a rebellion at Corfe Gate. The capstone of the Pavane saga.

ㅤ

Honorable Mention

The Suicide Express, by Philip José Farmer (another Riverworld tale)

Synth, by Keith Roberts (Is an android a person?)

Prisoners of the Sky, by C.C. McApp (saving the plateau world of Durrent from alien invaders)

—

Good novellas are usually few and far between. We raised a bumper crop this year!

——

Best Novel/Serial

——

Babel-17, by Samuel R. Delany

Hands down the winner. Brilliant linguist Rydra Wong must decipher the secret of the alien's language before more traitors bring down humanity from within. There's never been anything quite like this progressive masterpiece (though Purdom's I Want the Stars has hints of it).

ㅤ

Flowers for Algernon, by Daniel Keyes

Charlie Gordon is a moron…until he's a genius. What next? An expansion of the brilliant novelette, garnering the Galactic Star in both incarnations.

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, by Robert A. Heinlein

The Moon is a revolting place. Featuring the neatest synthetic character ever portrayed!

October the First is too Late, by Fred Hoyle

The world is fractured into a myriad of time zones, but why?

Sibyl Sue Blue, by Rosel George Brown

She's tiny, she's tough, and Sergeant Blue is going to crack the benzale murder case, even if she has to go to the stars to do it.

Make Room! Make Room!, by Harry Harrison

There is a critical density for humanity; Harrison's exploration of the Malthusian world is profoundly disturbing.

Honorable Mention

Sword of Lankor, by Howard Cory

Now Wait for Last Year, by Philip K. Dick

Earthworks, by Brian W. Aldiss

The Crystal World, by J.G. Ballard

Too Many Magicians, by Randall Garrett

—

The New Wave is definitely upon us, with only the Heinlein truly "conventional" SF (but the best he's turned in yet!) I am pleased that women are represented in each of these categories, though still dismayed at the relative dearth of them. This was a very lean year for woman-penned science fiction.

If there be a Hugo category for "Best Publisher" next year, we'll be surprised if Ace or Doubleday aren't among the nominees——they had, by far, the most outstanding books in 1966.

——

Best Science Fact

——

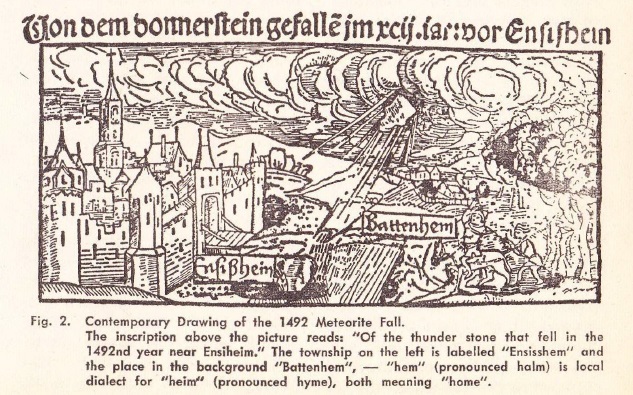

For Your Information: The Sound of the Meteors, by Willy Ley

ㅤ

Drifting Continents, by Robert S. Dietz

H. P. Lovecraft: The House and the Shadows, by J. Vernon Shea

BB or Not BB, That Is the Question, by Isaac Asimov

Dimensions in Heinlein, by Alexei Panshin

The Economics of SF, by John Brunner

Dimensions, Anyone?, by John D. Clark, Ph.D.

—

Asimov no longer dominates the field, in part because he's starting to struggle for material, and also because we're doing a better job of keeping up with the 'zines. These are all great articles, though. Accessible and interesting.

——

Best Magazine/Collection

——

Orbit: 3.36 stars, 3 Star nominees

Science Fantasy/Impulse: 3.23 stars, 6 Star nominees

New Worlds: 3.21 stars, 7 Star nominees

Fantastic: 3.20 stars, 2 Star nominees

New Writings: 3.13 stars, 1 Star nominee

F&SF: 3.099 stars, 10 Star nominees

Galaxy: 3.097 stars, 3 Star nominees

Alien Worlds: 3 stars, 1 Star nominee

IF: 2.91 stars, 7 Star nominees

Analog: 2.89 stars, 5 Star nominees

Worlds of Tomorrow: 2.66 stars, 3 Star nominees

Amazing: 2.37 stars, 1 Star nominee

—

This is always an apples and oranges category since collections are published much more rarely than magazines, some magazines are monthly while others are bi-monthly (or even quarterly), and both Fantastic and Amazing are composed mostly of reprints. Nevertheless, the two UK mags definitely stood out this year, with New Worlds slightly more experimental, and thus variable, than Science Fantasy. Galaxy is the more reliable, but also more stolid sister of IF. Worlds of Tomorrow does not seem long for this world…

——

Best Artist

——

——

Best Dramatic Presentation

——

A chilling documentary-style exploration of an atomic blast on England.

ㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤㅤ

Raumpatrouille Orion: "The Space Trap"

Out of the Unknown: "The Midas Plague"

Flight of the Phoenix (unreviewed, but boy is it good!)

——

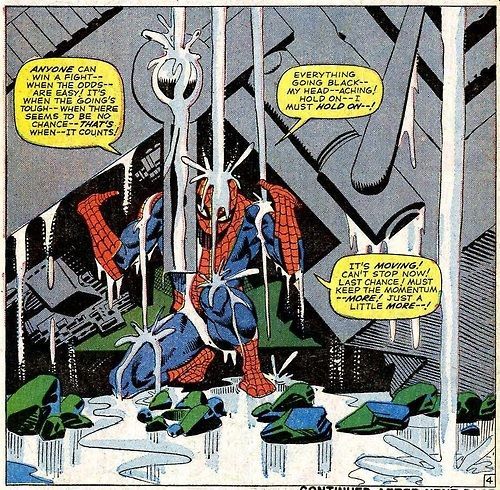

Best Comic Book

——

Spiderman

X-Men

ㅤ

Asterix in Britain

Blazing Combat

Doom Patrol

Fantastic Four

The Rise and Fall of the Trigan Empire

—

Marvel Comics is now in a dominating position, putting out some of the most dynamic, popular mags. National (DC) is barely keeping a toehold in with their FF-derived Doom Patrol. Beyond the Big Two, Blazing Combat, by Warren Publications, offers a much more nuanced, even anti-war alternative to Sgt. Rock and Sgt. Fury. France is represented with the Gaul-era Asterix in Britain, while Britain's Trigan Empire, appearing in Ranger and Look and Learn (sequentially) gets the Star for that nation.

Sadly, I've not been back to Japan since '64, which means I'm missing out on loads of terrific manga. Well, maybe next year…

——

Best Fanzine

——

Riverside Quarterly

Yandro

ㅤ

Amra

Australian Science Fiction Review

Lighthouse (annual pros' fanzine)

Nikeas

Ratatosk (news)

Science Fiction Times (news)

Tolkien Journal

Zenith

—

Riverside Quarterly, with its scholarly pieces, and Juanita Coulson's Yandro, one of the most balanced of 'zines, continue to impress. This will probably be the last year SFT makes it on the ballot given its reduced schedule. But with the recent republishing of LoTR, I expect Tolkien Journal to be with us a long time.

And so, another year's crop is harvested. I think, on the main, 1966 yielded superior fruit than '65. Women continue to be underrepresented, but also consistently produce some of the best material. Imagine what the field would be like with equal participation!

One big change is that science fiction is no longer entirely the province of the written word. With the arrival of Star Trek, Space Patrol Orion, and more SF themed shows in general, not to mention the flourishing of comic books, SF is diversifying, infiltrating the mainstream. What long-term effects this has remain to be seen: will science fiction dilute itself into pap? Or will it explode as the audience grows?

Stay tuned next year! Until then, keep watching the Stars…

![[December 26, 1966] Harvesting the Starfields (1966's Galactic Stars!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661226plough-672x372.jpg)

![[December 24, 1966] Unquiet on the Romulan Front (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Balance of Terror")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661224title-672x372.jpg)

![[December 14, 1966] (<i>Star Trek</i>: The Conscience of the King)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661214title-672x372.jpg)

![[November 30, 1966] Marking time (December 1966 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661130cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 22, 1966] Ha ha. Very funny. (December 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661122cover-661x372.jpg)

![[November 14, 1966] <i>Star Trek</i>: "The Corbomite Maneuver"](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661114title-672x372.jpg)

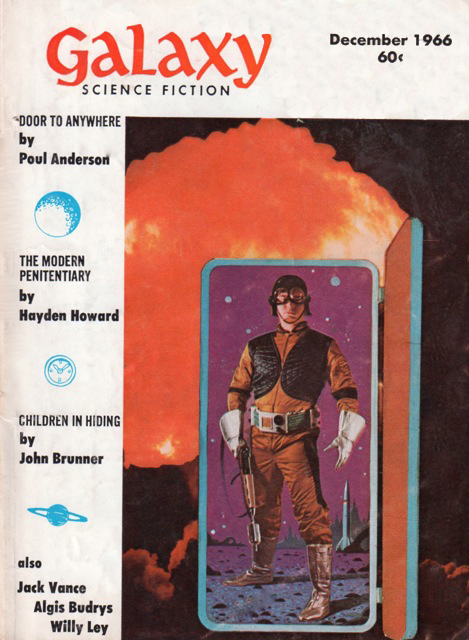

![[November 12, 1966] A Family Tradition (December 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661112cover-469x372.jpg)

![[November 4, 1966] <i>Star Trek</i>: "Miri"](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/661104title-672x372.jpg)

![[October 31, 1966] Respite from the horror (November 1966 <i>Analog Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/661031cover-355x372.jpg)

![[October 22, 1966] Why Johnny Should Read (November 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/661022cover-653x372.jpg)