[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

by Kaye Dee

We all breathed a sigh of relief when the astronauts of Apollo-13 returned to Earth safely a few days ago, after the Apollo programmes’ first (and hopefully last) inflight emergency, but superstitious people are claiming that Apollo-13 was unlucky because of a prevalence of “13s”! After all, the mission was launched at 13:13 Houston time (but somewhere in the world there will always be a place where the time is 13: something!) and the explosion that caused its inflight emergency occurred on 13 April (but only in certain timezones – it was already 14 April in Australia and most of the world east of the United States).

Don’t tell me the Apollo-13 crew were “unlucky”; in fact, they were immensely lucky that when something did go wrong they were a team with the right skills for the situation. As seasoned test pilots, the crew were experienced at working in critical situations with their lives on the line, and their professional skills as astronauts were matched by the “tough and competent” (to quote Flight Director Mr. Gene Kranz) Mission Control teams, backed by highly trained engineers and scientists – all determined to “return them safely to the Earth”, just as President Kennedy committed NASA to do when he set the goal of a manned lunar landing by 1970!

Timeline of major mission events during Apollo-13

Timeline of major mission events during Apollo-13

Crew Switcheroo

The prime crew for Apollo-13 changed multiple times, the last alteration occurring just days before launch! Instead of rotating the Apollo-10 back-up crew to become the prime crew for Apollo-13 – the normal procedure – Director of Flight Crew Operations, Mr. Deke Slayton, designated astronauts Alan Shepard (Commander), Stuart Roosa (Command Module Pilot) and Edgar Mitchell (Lunar Module Pilot) as the Apollo-13 prime crew. However, although he was the first American in space, Captain Shepard had only recently returned to flight status after a lengthy medical issue. It was felt that he needed more training time, so in August 1969, his crew was swapped with the prime crew for Apollo-14.

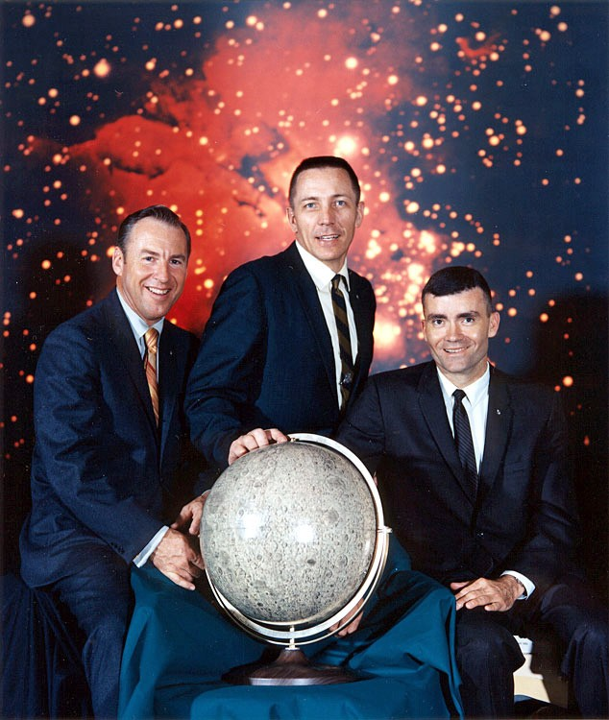

The prime crew for Apollo 13 then became US Navy Captain James Lovell, as Commander, civilian Mr. Fred Haise as Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) and USAF Lt. Col. Ken Mattingly as Command Module Pilot (CMP).

Official crew portrait for Apollo-13. L.-R. Jim Lovell, Ken Mattingly and Fred Haise. They are shown with ancient scientific and navigation instruments hinting at the classical elements in the mission patch and callsigns

Official crew portrait for Apollo-13. L.-R. Jim Lovell, Ken Mattingly and Fred Haise. They are shown with ancient scientific and navigation instruments hinting at the classical elements in the mission patch and callsigns

Unfortunately, just a week before launch back-up LMP Charles Duke contracted German measles (rubella) from a child and accidentally exposed both the prime and back-up crews to the disease. CMP Mattingly was found to have no immunity, and the astronauts’ medical team had serious concerns that he could become too sick to perform adequately during the flight if he began to experience symptoms of the disease.

Normally, NASA policy would dictate that the back-up crew step into the mission. However, since back-up LMP Duke also had the measles, this wasn’t feasible. Just three days before launch, the difficult decision was made to replace Lt. Col. Mattingly with Mr. Jack Swigert, the fortunately-immune back-up CMP. This made the final crew for Apollo-13 Lovell, Haise and Swigert. Astronaut Mattingly will be re-assigned to a later Apollo mission, probably Apollo 16.

The last minute Apollo-13 crew portrait, following the swap of Ken Mattingly to Jack Swigert

The last minute Apollo-13 crew portrait, following the swap of Ken Mattingly to Jack Swigert

Who’s Who?

Although he announced his intention to retire from NASA prior to Apollo-13, 42-year-old Mission Commander James “Jim” Lovell is the world's most experienced astronaut, the record holder for the most time in space, with 572 hours aboard Gemini-7, Gemini-12 and Apollo-8!

Members of the fifth astronaut group, selected in 1966, Captain Lovell’s crewmates may have both been space rookies, but fortuitously they each had specialisations that provided vital knowledge and experience during the in-flight emergency.

Mr. Fred Haise, the Lunar Module pilot (LMP), is a 36-year-old aeronautical engineer, who was both a Marine Corps and Air National Guard fighter pilot. A civilian research pilot for NASA before his selection as an astronaut, Mr. Haise previously served as back-up LMP for Apollo-8 and 11. He is a specialist on the Lunar Module (LM), having spent fourteen months at the Grumman factory where the spacecraft are built.

Mr. John “Jack” Swigert, the Command Module Pilot (CMP), is 38 years old, with degrees in mechanical engineering and aerospace science. He has served in the US Air Force and in state Air National Guards and was an engineering test pilot immediately prior to his astronaut selection. A specialist in malfunctions of the Command and Lunar Modules, Mr. Swigert “practically wrote the book on spacecraft malfunctions.”

Knowledge from the Moon

It’s probably fortunate that, like Apollo-11, Captain Lovell’s original crew made the decision that the Apollo-13 mission patch would not carry their names: when the last minute crew swap occurred, no changes were required to the design. Instead of names, the Apollo-13 patch carries the motto “Ex Luna, Scientia”, Latin for “From the Moon, knowledge”. This references Apollo-13’s intended role as the second ‘H’-class mission, designed to demonstrate precision landing capability so that the crew could explore a specific site on the Moon. As a Navy officer, Captain Lovell derived the motto from that of the US Naval Academy, “Ex scientia, tridens ("From knowledge, sea power").

A powerful image of the Sun rising behind the horses of the god Apollo’s chariot forms the centrepiece of the design. As Apollo is the god of both the Sun and knowledge, this plays upon both the project name and the mission motto. Against the black background of space, the golden horses of Apollo prance over the Moon, their journey from the Earth (in the background) to the Moon depicted by a bright blue path. Artist Lumen Martin Winter, designer of the Apollo-13 mission patch, based the horses on a mural he previously painted for the St. Regis Hotel in New York City (below). Using Roman numerals for the mission number also complements the classical connections of the spacecraft names and callsigns.

Classical Callsigns

Captain Lovell drew upon classical mythology in selecting the Command Module callsign “Odyssey” – taken from Homer’s epic Greek poem. Since an “odyssey is “a long voyage with many changes of fortune”, it turned out to be an extremely appropriate choice indeed! The name was also a nod to the classic science fiction film "2001: a Space Odyssey".

For the Lunar Module, the crew selected the callsign “Aquarius”. Although the media have linked the callsign to the song in the musical “Hair”, it is actually meant to reference Aquarius, the cup-bearer of the Graeco-Roman gods, and bringer of water – the only water on the Moon being that carried there by the Apollo crew.

Medieval illustration of Aquarius watering the Earth

Medieval illustration of Aquarius watering the Earth

Preflight Preparations

Apollo-13’s launcher, AS-508, had some slight modifications compared to earlier Saturn-V vehicles, to prepare for the future J-class missions which will carry heavier payloads. New “spray-on insulation” was used for the liquid hydrogen propellent tanks in the S-II second stage. The rocket also carried additional fuel, as a test for future launches, making it the heaviest Saturn-V yet flown.

The intensive preparation for the Apollo-13 crew included over 1,000 hours of mission-specific training, with a much greater focus on geology, since the intended landing area in the hilly Fra Mauro formation (named for a 15th Century cartographer monk) is of significant geological interest. If rocks from this area could be dated, they might improve our understanding of the early geological history of both the Moon and the Earth. Scientist-astronaut Harrison Schmitt, himself a geologist, was heavily involved in the crew’s geological training.

Jim Lovell and Fred Haise during geology training in Hawaii

Jim Lovell and Fred Haise during geology training in Hawaii

Due to the difficulty of distinguishing astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin from each other in Apollo-11 photographs, NASA introducec a means of differentiating crew members from each other on the Moon by adding red stripes on the helmet, arms and legs of the commander's spacesuit. This system will now be implemented on Apollo-14.

Experiments That Might Have Been

A major component of Apollo-13’s lunar surface activities would have been the installation of a new Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package (ALSEP), powered by a SNAP-27 radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG). This small nuclear generator contains 8.36lb of plutonium oxide. The fuel capsule is intended to withstand the heat of re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere in the event of an aborted mission, which means that Apollo-13’s RTG may have survived Aquarius’ re-entry on return to Earth, splashing down into a remote area of the southern Pacific Ocean.

Mission Commander Lovell practicing the deployment of an ALSEP instrument during training

Mission Commander Lovell practicing the deployment of an ALSEP instrument during training

Like Apollo-11 and 12, Apollo-13’s ALSEP included a seismometer (the Passive Seismic Experiment), which was to be calibrated by the impact of Aquarius’ ascent stage, a Lunar Atmosphere Detector (LAD) and a Dust Detector. New to the Apollo-13 instrument package was a Heat Flow Experiment (HFE), and a Charged Particle Lunar Environment Experiment (CPLEE), designed to measure solar protons and electrons reaching the Moon.

A Shakey Start

Originally scheduled for launch in March, Apollo-13 was delayed for a month while NASA re-considers how it will schedule the remaining Apollo missions out to Apollo-19, now that Apollo-20 has been axed due to President Nixon’s budget cuts.

The mission hit trouble right at the start: five and a half minutes after liftoff on Saturday 11 April (US time). The crew felt “a little vibration”, then the centre engine of the S-II stage shut down two minutes early. This required the remaining four engines to burn and additional 34 seconds longer, while the S-IVB third stage had to burn 9 seconds longer to put the spacecraft into orbit. But with the extra fuel on board for this flight, the engine failure fortunately didn’t cause any major problem.

A successful trans lunar injection burn placed Apollo-13 on course for the Moon, with the CSM and LM docking occurring 20 minutes’ later. Unlike previous lunar missions, after the LM was extracted from the S-IVB stage, the stage was not sent off into solar orbit, but targetted to impact the Moon so the vibrations could be detected by the Apollo-12 seismometer. This would later cause unexpected communications complications after the accident occurred.

Apollo-13's S-IVB stage heading towards the Moon

Apollo-13's S-IVB stage heading towards the Moon

“We’re Bored to Tears”

With the spacecraft safely on its way to the Moon, the first phase of the flight was uneventful. Approaching 31 hours into the flight, the crew performed a burn to place Apollo 13 on a hybrid trajectory, enabling Aquarius to ultimately land at the Fra Mauro site. This change from the free-return trajectory used on earlier missions would cause later complications for returning the astronauts to Earth: on a free-return trajectory, no further engine burns were necessary to ultimately bring the spacecraft home, but a hybrid trajectory would miss Earth on its return leg, unless further burns were performed.

Apollo-13 White Team Flight Director Mr. Gene Kranz catching up on his paperwork in Mission Control during the calm before the storm

Apollo-13 White Team Flight Director Mr. Gene Kranz catching up on his paperwork in Mission Control during the calm before the storm

The day after launch, Mr. Swigert became worried by the realisation that, in the rush to replace Ken Mattingly, he had forgotten to file his Income Tax Return, and needed to apply for an extension! Fortunately for him, an amused Mission Control advised that “American citizens out of the country get a 60-day extension on filing; assume this applies to you.”

With Apollo-13’s telemetry showing that the spacecraft was “in real good shape”, on 13 April Capcom Joe Kerwin told the crew “We are bored to tears down here.”—a situation that was soon to change.

The Last Apollo-13 Show

Astronauts Lovell and Haise entered the LM to test its systems about an hour before a major television broadcast, scheduled for 55 hours into the mission.

With Commander Lovell acting as MC, the astronauts put on a lively show, exhibiting some of their gear such as space helmets, sleeping hammocks and newly-designed bags for drinking water inside their spacesuits. From Odyssey, Captain Lovell played tinkly lounge music using a small tape recorder, and he said it was an awesome thing to see the Moon accompanied by the theme to 2001.

Mission Control during the Apollo-13 broadcast. Astronaut Fred Haise can be seen on the big screen

Mission Control during the Apollo-13 broadcast. Astronaut Fred Haise can be seen on the big screen

Disappointingly, American television viewers had become, it seems, even more bored than Mission Control with now-“routine” missions to the Moon. None of the major US networks carried the broadcasts, although they were seen in Australia and, I believe, other countries. Marilyn Lovell and Mary Haise had to go to the Mission Control VIP viewing room to see their husbands’ half hour broadcast on television.

“Houston, We’ve had a Problem Here!”

Just nine minutes after the conclusion of the television broadcast, at 205,000 miles from Earth, an incident occurred that turned Apollo-13 from a routine mission into an emergency situation: one that the media and anxious communities in the US and around the world would intently follow as soon as the news broke!

At the request of Mission Control, Mr. Swigert stirred the cryogenic hydrogen and oxygen tanks that powered the fuel cells in the Service Module (SM). This action was followed by a “pretty large bang”, felt as a jolt through the spacecraft, accompanied by fluctuations in electrical power, attitude control thrusters firing automatically and a brief loss of communications and telemetry to Earth.

Diagram of the Service Module showing the location of the fuel cells and oxygen tanks that must have been damaged by the explosion, based on the available telemtry

Diagram of the Service Module showing the location of the fuel cells and oxygen tanks that must have been damaged by the explosion, based on the available telemtry

CMP Swigert quickly reported "Okay, Houston, we've had a problem here," confirmed moments later by the Mission Commander, "Houston, we've had a problem. We've had a Main B Bus undervolt”. This meant that the SM’s three fuel cells were not providing sufficient voltage to the second of the Service Module’s two electrical power distribution systems

Captain Lovell momentarily thought that LMP Haise had activated Aquarius’ cabin-repressurisation valve (which Haise could have done as a joke, since its bang would startle his crewmates); CMP Swigert initially thought that a meteoroid might have struck the LM, though there was no atmospheric leakage. But voltage was dropping in both electrical buses, one oxygen tank was empty, and the other leaking, and two of the three fuel cells were failing!

Headline from Australian newspaper "The Sun" just a few hours after the accident. It references Lovell's description of gas venting from the Service Module

Headline from Australian newspaper "The Sun" just a few hours after the accident. It references Lovell's description of gas venting from the Service Module

Looking out Odyssey’s hatch window, seeking a cause for the spacecraft thrusters to be firing erratically and affecting their course to the Moon, Captain Lovell saw “gas of some sort” venting into space. Some kind of physical rupture had definitely occurred: whatever had caused the problem, the situation was serious.

Mission Control Swings into Action

Although the Flight Controllers in Houston initially assumed that their bizarre anomalous readings from Apollo-13 had to be the result of instrumentation issues, it quickly became obvious, judging from the reports from the crew, that they were dealing with a genuine emergency.

The Mission Control White Team, led by Flight Director Gene Kranz, was on duty when the incident occurred and had to deal with the initial hours afterwards. With extensive Flight Director experience going back to the Mercury programme, and including critical phases of the Apollo-11 mission, Mr. Kranz played a crucial role in the rescue of the Apollo-13 crew.

Flight Director Gene Kranz (seated) and senior Flight Controllers during the tense period following the Apollo-13 accident

Flight Director Gene Kranz (seated) and senior Flight Controllers during the tense period following the Apollo-13 accident

With telemetry data providing some insight into the condition of the spacecraft, and support from “backroom” teams of technical specialists, White Team worked to diagnose the problems and prioritise recovery and rescue actions.

The fuel cells needed oxygen to operate, but it was rapidly leaking away. Attempting to stem the leak, they shut down the two failing fuel cells. This immediately meant the loss of the lunar landing, as mission rules prohibited going into orbit around the Moon unless all three fuel cells were functioning. With oxygen still being lost, Mr. Kranz ordered the isolation of a small oxygen supply within the Odyssey, to retain it for use with the last remaining fuel cell, which would be needed for the final hours of the mission. The CM's batteries would be needed to power the craft during re-entry, so they were also shut down to conserve power.

Lifeboat Aquarius

Ninety-three minutes after the accident, oxygen pressure in the Command Module was dropping and Mission Control determined that the last fuel cell would soon fail as oxygen ran out, leaving the CM effectively dead. Aware of training simulations that had used the LM as a “lifeboat”, Mission Control ordered the crew to transfer to Aquarius.

Lovell, Haise and Swigert had themselves already realised that Aquarius would be needed as a lifeboat, and had commenced to power-up the Lunar Module, transferring necessary information to the LM’s guidance system. They bagged up as much water as possible from Odyssey’s supply (needed for equipment cooling as well as drinking), storing the water and food supplies in Aquarius.

The Apollo-13 crew's only view of their lifeboat Aquarius in space, drifting after it was cast loose shortly before re-entry

The Apollo-13 crew's only view of their lifeboat Aquarius in space, drifting after it was cast loose shortly before re-entry

It was going to be a tight fit for three astronauts in a spacecraft meant for two, but the crew were fortunate that the emergency occurred when they had a fully-powered and supplied Lunar Module attached to the Odyssey. Had the explosion occurred after the lunar landing, with Aquarius jettisoned, the CM would not be able to provide enough life support to keep the astronauts alive until they returned to Earth.

Apollo-13 was being surrounded by a cloud of debris from the explosion. Communications were weak and erratic, due to probable antenna damage from debris, as well as interference from the S-IVB stage also on its way to the Moon. Its tracking beacon was operating on the same frequency as the Lunar Module, as it had not been anticipated that the LM and S-IVB stage would be communicating at the same time. (I’ll cover this situation in more detail in an article in May).

Flight Controllers conferring on how best to bring Apollo-13 safely home. Note the lack of data usually present on the big screens

Flight Controllers conferring on how best to bring Apollo-13 safely home. Note the lack of data usually present on the big screens

“Returning Them Safely to the Earth”

Apollo-13’s new mission goal became the safe return of the crew to the Earth. Vital consumables (oxygen, electricity, and water) were assessed and rationing plans devised. Calculating the best way to get the spacecraft back to Earth before supplies were exhausted became a priority, with the mindset that “failure is not an option”.

Ultimately, the safest course of action was deemed to be putting Apollo-13 back on a free-return trajectory, firing the LM’s descent engine so that the spaceship would loop around the Moon and head back to Earth. Using the large Service Module engine was ruled out, since it was uncertain if it had been damaged by the explosion.

NASA’s “Return to Earth” trajectory specialist, Miss Poppy Northcutt, calculated a new course to carry Apollo-13 around the Moon and safely home. Anxious to assist in any way they could, other astronauts arrived at Mission Control, including Lt. Col. Mattingly, who still had not developed German measles! Some would spend time in the Apollo simulators, helping to work up needed procedures, such as powering up the Command Module for re-entry with limited electricity available.

NASA Contollers and astronauts gathered in Mission Control to assist the rescue of Apollo-13. Seated, left to right, Guidance Officer Raymond F. Teague; astronaut Edgar D. Mitchell, Apollo 14 prime crew lunar module pilot; and astronaut Alan B. Shepard Jr., Apollo 14 prime crew commander. Standing, left to right, are scientist-astronaut Anthony W. England; astronaut Joe H. Engle, Apollo 14 backup crew lunar module pilot; astronaut Eugene A. Cernan, Apollo 14 backup crew commander; astronaut Ronald E. Evans, Apollo 14 backup crew command module pilot; and M.P. Frank, a flight controller

NASA Contollers and astronauts gathered in Mission Control to assist the rescue of Apollo-13. Seated, left to right, Guidance Officer Raymond F. Teague; astronaut Edgar D. Mitchell, Apollo 14 prime crew lunar module pilot; and astronaut Alan B. Shepard Jr., Apollo 14 prime crew commander. Standing, left to right, are scientist-astronaut Anthony W. England; astronaut Joe H. Engle, Apollo 14 backup crew lunar module pilot; astronaut Eugene A. Cernan, Apollo 14 backup crew commander; astronaut Ronald E. Evans, Apollo 14 backup crew command module pilot; and M.P. Frank, a flight controller

Sixty one and a half hours after launch, Aquarius’ descent engine burn put Apollo-13 back on a free return trajectory. As it looped around the Moon, Apollo-13 captured the Guinness World Record for the farthest distance from Earth attained by a crewed spacecraft – 248,655 miles.

The Moon's far side photographed by the Apollo-13 crew. The shut down CM Odyssey can also be seen in the foreground of this view from Aquarius

The Moon's far side photographed by the Apollo-13 crew. The shut down CM Odyssey can also be seen in the foreground of this view from Aquarius

I’m sure you recall the tension during those 25 minutes of radio blackout when Apollo-13 was behind the Moon. People around the world tuned into television and radio, or gathered in public spaces, eager for news, now engrossed in the gripping drama being played out in space. Would the astronauts survive? Religious leaders led congregations in prayer for their safe return.

On Their Way Home

Mission Control determined that a burn following trans-Earth injection would shave 12 hours off the flight time back to Earth and land Apollo-13 in the Pacific, where the main US recovery fleet was located. Thirteen nations (another number 13!), including the USSR, offered to provide rescue ships or aircraft for emergency recovery, should the spacecraft come down off course in the Pacific, Indian or Atlantic Oceans.

When this crucial burn took place, the debris cloud surrounding the spacecraft made it impossible to use stellar navigation to check the accuracy of the firing. However, the crew were able to use the positions of the Sun and Moon to confirm that the trajectory was on target. They were going home!

The astronauts then shut down most LM systems to conserve consumables, making for a miserable return flight: in Aquarius it was extremely cold (38 °F), dark and damp, with moisture condensing out on every surface, including the windows. The same issue occurred in Odyssey, raising concerns of short-circuits occurring when it was powered back up. Fortunately, lessons learned from the Apollo-1 fire prevented that from happening.

Mission Commander Lovell tries to sleep in the extreme cold and semi-darkness of the Lunar Module

Mission Commander Lovell tries to sleep in the extreme cold and semi-darkness of the Lunar Module

The crew slept poorly, eating and drinking little (cold frankfurters and water for dinner, anyone?). They lost weight, with Mr. Haise developing a urinary tract infection, apparently from dehydration.

Putting a Square Peg in a Round Hole

A new problem arose during the return journey – with three astronauts in the LM, dangerous levels of carbon dioxide were building up in Aquarius. They were running out of lithium hydroxide canisters, designed to scrub it from the air, and the square canisters used in Odyssey were not compatible with the round openings in Aquarius!

Jack Swigert, with assistance from Jim Lovell (just out of frame) assembles the connections for the makeshift CO2 scrubbing device nicknamed "the mailbox", which is box shaped object beside Swigert

Jack Swigert, with assistance from Jim Lovell (just out of frame) assembles the connections for the makeshift CO2 scrubbing device nicknamed "the mailbox", which is box shaped object beside Swigert

NASA engineers fortunately found a way to fit “a square peg in a round hole,” using only items available on the spacecraft. After the instructions for building the device were radioed up, Swigert and Haise constructed it and carbon dioxide levels began dropping immediately.

The Final Leg

Apollo-13 showed a tendency to drift slowly off course, and two more mid-course correction burns were needed to keep the spacecraft within the safe re-entry flight path. Just after 138 hours into the mission, the crew jettisoned the SM from the command module, allowing the astronauts to see and photograph the explosion area for the first time. They were shocked by the extent of the damage they saw and concerned that the explosion might have damaged the heatshield.

The astronauts' only view of the Service Module, showing the extent of the damage caused by the explosion, which blew out an entire side panel.

The astronauts' only view of the Service Module, showing the extent of the damage caused by the explosion, which blew out an entire side panel.

Moving back into Odyssey, the astronauts then reactivated its life support systems, while retaining Aquarius until about 70 minutes before entry. With no heatshield of its own, the LM could not safely re-enter, but as it drifted away, watched sadly by the crew, Capcom Kerwin offered an epitaph from Mission Control: “Farewell Aquarius, and we thank you”.

There's no place like home! Earth taken from Apollo-13 in the final stages of its return from the Moon

There's no place like home! Earth taken from Apollo-13 in the final stages of its return from the Moon

Home at Last!

At last, on April 17 (US time),142 hours after launch, Apollo-13 re-entered Earth’s atmosphere. Its shallow re-entry path lengthened the usual four-minute radio communications blackout to six minutes, causing Mission Control to briefly fear that the CM's heat shield had failed. But Odyssey had survived and splashed down safely in the South Pacific Ocean south-east of American Samoa, just four miles from the recovery ship, USS Iwo Jima: total flight time: 5 days, 22 hours, 54 minutes and 41 seconds. Mission Control erupted in cheers!

While the world rejoiced at their safe return, the exhausted Apollo-13 crew stayed overnight on the recovery ship, without undergoing quarantine since they did not land on the Moon.

Exhausted but elated, the Apollo-13 crew are formally welcomed aboard the recovery ship, USS Iwo Jima as returning heroes after their space ordeal

Exhausted but elated, the Apollo-13 crew are formally welcomed aboard the recovery ship, USS Iwo Jima as returning heroes after their space ordeal

The astronauts flew to Pago Pago in American Samoa the next day, then on to Hawaii, where they were re-united with their wives and President Nixon awarded them the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest US civilian honour. The Presidential Medal of Freedom was also awarded to the Apollo-13 Mission Operations Team, for their efforts in ensuring the safe return of the Apollo-13 crew. After staying overnight in Hawaii, Capt. Lovell, Mr. Haise and Mr. Swigert have now returned to Houston to be re-united with their families.

Returning heroes after their space ordeal. the Apollo-13 crew stand proudly with President Nixon after being awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom

Returning heroes after their space ordeal. the Apollo-13 crew stand proudly with President Nixon after being awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom

At present, the cause of the explosion that crippled Apollo-13 is unknown, so I will leave the speculation until my follow-up article in May, talking more about Apollo-13’s epic journey. I’d like to end here with the words of President Nixon, during the Presidential Medal of Freedom presentation: “You did not reach the Moon, but you reached the hearts of millions of people on Earth by what you did.”

The astronauts only learned about the extent of the pubic reaction to their emergency after they returned to Earth!

The astronauts only learned about the extent of the pubic reaction to their emergency after they returned to Earth!

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]