by Kaye Dee

Riding on Apollo's Coat-tails

The Traveller recently referred to President Nixon’s 8-day European tour, but it would seem Mr. Nixon deliberately decided to pave the way by riding on the coat-tails of the general international applause accorded to the historic Apollo-8 mission. Shortly before he announced his own trip to Europe, the President personally dispatched Apollo-8 commander Colonel Frank Borman and his family on an eight-nation European goodwill tour. (The other Apollo-8 crewmembers, already in training as part of the Apollo-11 backup crew, were not available to participate in the tour.)

Departing on 2 February, Col. Borman, his wife Susan, and two sons undertook a 19-day tour, visiting the UK, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, West Germany (including West Berlin), Italy (including Vatican City), and Spain (like Australia, home to an Apollo Manned Space Flight Network station and a Deep Space Network facility): an itinerary very closely paralleling that later followed by President Nixon!

The Borman family meets the Royal Family and Col. Borman presents a picture of the Moon to the Pope during his goodwill tour of Europe

The Borman family meets the Royal Family and Col. Borman presents a picture of the Moon to the Pope during his goodwill tour of Europe

Col. Borman said that he was particularly gratified to make the journey because of a conviction that space efforts “can be a very positive force for creating better relations among the people of the world”.

A Long-Delayed Mission

But while Colonel Borman was embarking on his diplomatic mission, the crew of the long-delayed first test flight of the Lunar Module (LM) in Earth orbit were in the final stages of preparations for the Apollo-9 mission, which splashed down just a few days ago with all its objectives successfully completed. Intended to be Apollo-8, the mission was bumped later in the sequence due to a succession of technical delays in the development of the LM, the first manned spacecraft designed solely for operations in space.

Apollo-9’s main task was to qualify the LM for manned lunar flight, demonstrating that the craft could perform all the necessary manoeuvres required for a landing on the Moon. The flight was therefore intended to be very much a mission of “firsts” that would finally fully test-out the entire suite of hardware needed to accomplish a Moon landing mission. It would see the first flight of the complete Apollo Saturn vehicle – Saturn V launcher (AS-504 for this mission), Command Service Module (CSM-104) and Lunar Module (LM-3) – as well as the first docking and extraction of a LM from the Saturn S-IVB stage.

Putting the LM through its paces would involve the first flight tests of its upper and lower stages, with the first firings of their engines in space, and include the first rendezvous and docking between with the CSM and LM. The mission would also undertake the first spacewalk of the Apollo programme, to test the reliability of the Apollo A-7L space suit and the Portable Life Support System (PLSS) backpack, essential for lunar surface operations.

The Crew Who Waited

Original 1966 crew photo of Astronauts Scott, McDivitt and Schweickart. Their training for the flight that eventually became Apollo-9 commenced in January 1967, even before the Apollo-1 fire

Original 1966 crew photo of Astronauts Scott, McDivitt and Schweickart. Their training for the flight that eventually became Apollo-9 commenced in January 1967, even before the Apollo-1 fire

Probably the best prepared mission crew to date, the Apollo-9 crew originally came together in January 1966, as the back-ups for Apollo-1, before being assigned as the first crew to fly the LM. Their 1,800 hours of mission-specific training was equivalent to about seven hours for every hour of their eventual flight!

With so much riding on a successful LM test flight, Apollo-9’s crew comprised two veteran Gemini astronauts and one rookie. Mission Commander Air Force Col. James McDivitt previously commanded the Gemini-IV mission, during which the first US EVA was conducted. Command Module Pilot Lt.-Col. David Scott, also with the US Air Force, was Pilot of Gemini-VIII, its flight cut short by the first US in-flight space emergency, but for which he undertook considerable EVA training.

Finally Go for launch! Astronauts McDivitt, Scott and Schweickart in their official Apollo-9 pre-flight crew portrait

Finally Go for launch! Astronauts McDivitt, Scott and Schweickart in their official Apollo-9 pre-flight crew portrait

The new kid on the block for Apollo-9 was LM Pilot Mr. Russell Schweickart, originally selected in the third group of astronauts in 1963. An experienced fighter pilot, serving with the U.S. Air Force and the Massachusetts Air National Guard between 1956 and 1963, Mr. Schweickart joined NASA as a civilian, from a position as a research scientist at the Experimental Astronomy Laboratory of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Mr. Schweickart is nicknamed “Rusty” for his red hair (but in Australia, with our sense of humour, we’d have called him “Bluey”!).

Introducing Gumdrop and Spider

Because Apollo-9 would have two spacecraft from the same mission operating independently for the first time (unlike the Gemini VI-VII rendezvous, in which the two spacecraft were separate missions with their own callsigns), they each required separate callsigns for easy communications identification. NASA Administrators therefore finally lifted the ban on spacecraft names, which has been in operation since the beginning of the Gemini programme, permitting the crew to select their own names for the CM and LM.

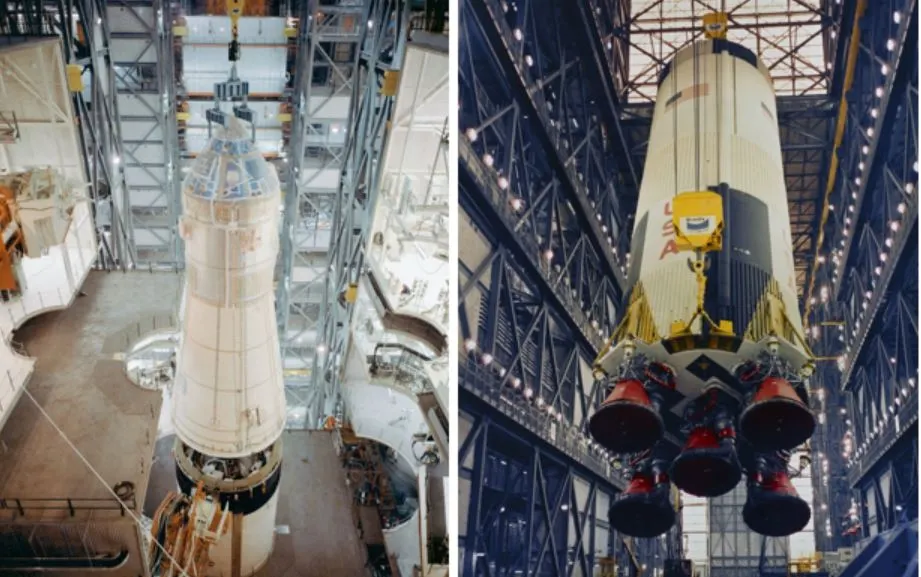

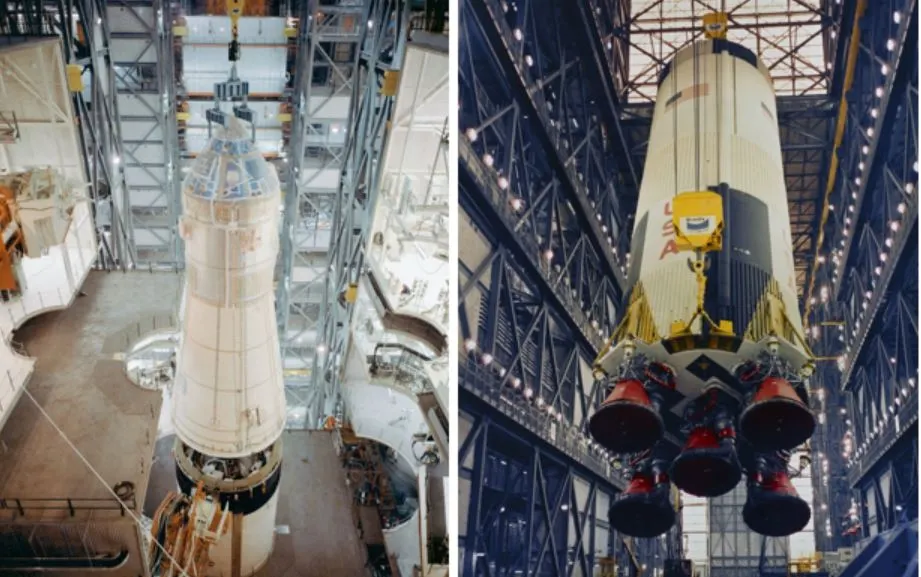

The Apollo-9 CSM and LM being prepared for launch at Kennedy Space Centre

The Apollo-9 CSM and LM being prepared for launch at Kennedy Space Centre

The astronauts chose “Gumdrop” for the CM, based on the shape of the capsule, which resembles the popular sweet, and “Spider” for the LM, given the spider-like appearance of the lander, with its four spindly legs. Unfortunately, it seems that certain NASA officials were not happy with these choices, feeling they were not dignified enough, so I hope they will not place restrictions on the names that can be selected for future missions, or force the crews to revert to dull numerical callsigns.

Patching Up

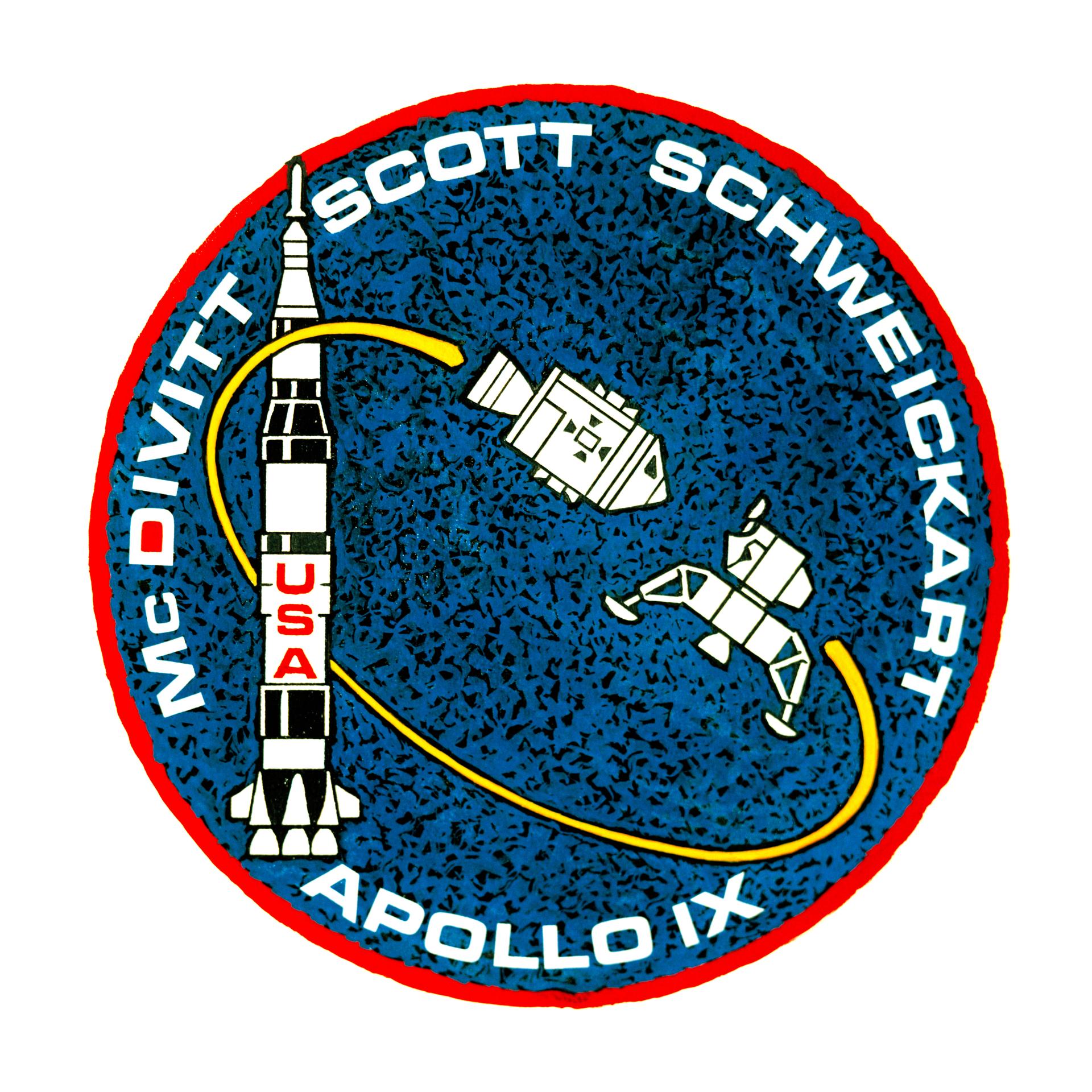

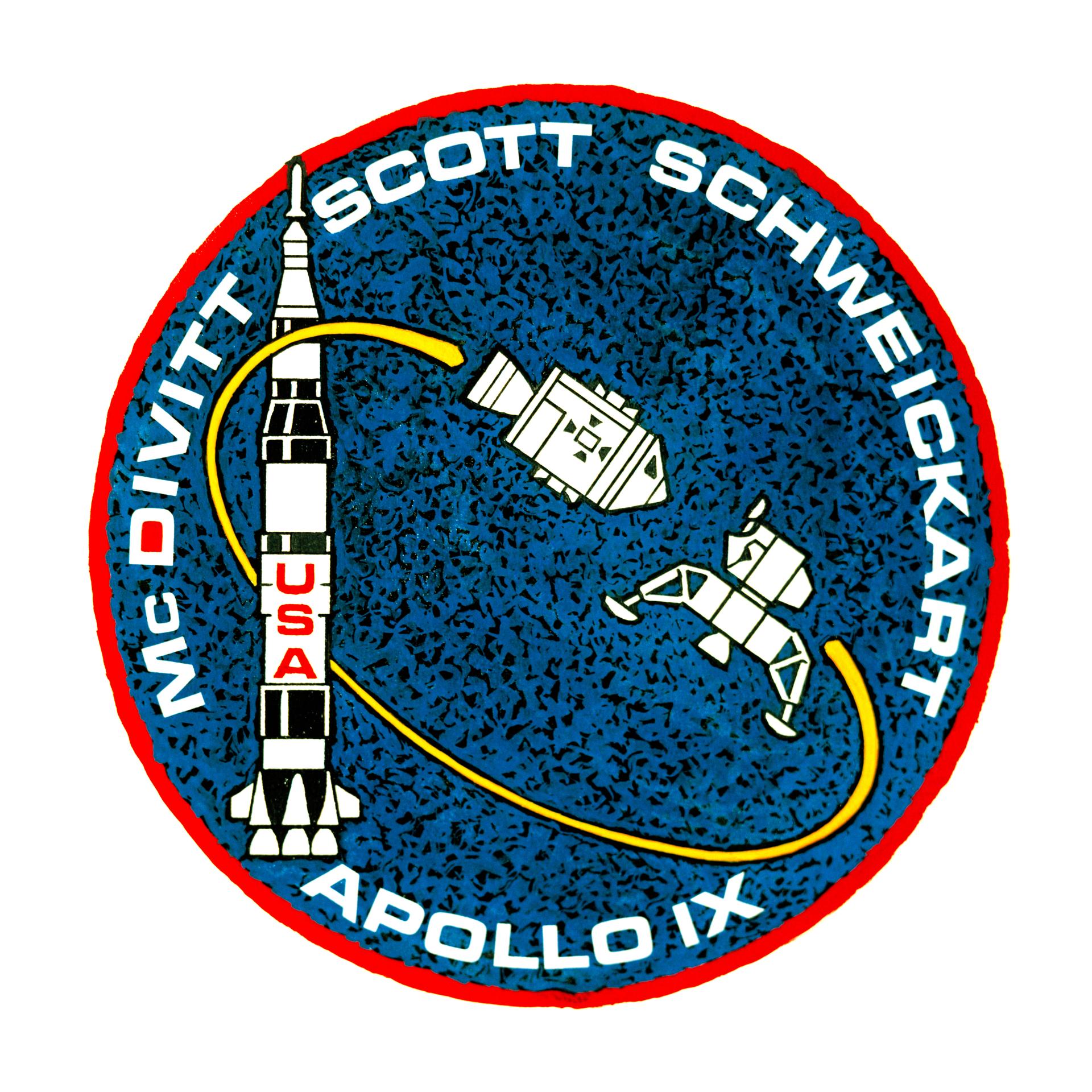

North American Rockwell artist Allen Stevens seems to be quite a favourite with the Apollo astronauts as a mission patch designer. He has designed the patches for Apollo-1, 7 and Apollo-9, and seems to have had a strong influence on the design of the Apollo-8 patch.

Stevens’ Apollo-9 patch evolved from a design he originally developed when Apollo-9 was still anticipated to be Apollo-8. The relatively simple concept depicts all the vehicle elements of the Apollo mission – the Saturn V in launch configuration, with the CSM and the LM flying separately as they would do during orbital test manoeuvres. In the final version of the design they appear against a mottled blue background that could represent either the Earth’s oceans or orbital space.

Stevens’ Apollo-9 patch evolved from a design he originally developed when Apollo-9 was still anticipated to be Apollo-8. The relatively simple concept depicts all the vehicle elements of the Apollo mission – the Saturn V in launch configuration, with the CSM and the LM flying separately as they would do during orbital test manoeuvres. In the final version of the design they appear against a mottled blue background that could represent either the Earth’s oceans or orbital space.  Rather than show the CSM and LM docked together in orbit, as we often see them in NASA illustrations, Stevens chose to depict them in their on orbit ‘station-keeping’ positions, with the CSAM and LM facing each other, although this does give the impression that the CM is attempting to dock with the front of the LM!

Rather than show the CSM and LM docked together in orbit, as we often see them in NASA illustrations, Stevens chose to depict them in their on orbit ‘station-keeping’ positions, with the CSAM and LM facing each other, although this does give the impression that the CM is attempting to dock with the front of the LM!

Completing the design, the names of the crew and mission circle just inside the red-bordered edge of the patch, with the “D” in McDivitt’s name also filled in red. This is a nod to Apollo-9 being originally designated as the “D” mission in the sequence of Apollo flights prior to the Moon landing.

A Busy Moonport

Due to the long delay with the LM, preparations for Apollo-9 initially overlapped those of Apollo-7 and 8. By February, while the astronauts were spending long hours in mission simulators preparing for their flight, Kennedy Space Centre (KSC) was a hive of activity with Apollo-9 in the final stages of pre-launch testing, and advance preparations for Apollo 10 and Apollo 11 also underway (Apollo 10 is currently due for launch in May and Apollo 11 in July).

In addition to Apollo-9’s launch preparations, the Apollo 10 spacecraft was moved from the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building (MSOB) to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) for mating with its Saturn V launcher (above left); the first and second stages for the Apollo 11 Saturn V arrived, with the stacking of that launcher commencing in the VAB (above right); and the upper and lower stages of the Apollo 11 LM were also mated in the MSOB, in preparation for testing in the altitude chamber. NASA is really moving at a cracking pace to achieve a manned lunar landing this year!

An Unexpected Delay

The countdown for Apollo-9 commenced on 26 February, for a planned launch on the 28th. But fate stepped in to delay the crew’s trip to space just a bit longer! Ironically, despite their years of training for this mission, the astronauts pushed themselves so hard in their final weeks that, as launch day approached, they developed cold-like symptoms such as sore throats and nasal congestion.

Apollo-9's LM crew, McDivitt and Schweickart, training in the Lunar Module simualator

Apollo-9's LM crew, McDivitt and Schweickart, training in the Lunar Module simualator

For NASA’s most complex manned mission to date, senior managers and flight surgeons wanted the crew to be in the best possible health for the 10-day flight. (They were probably also mindful of preventing a recurrence of the issues with the Apollo-7 crew, due to in-flight health problems). Consequently, the launch was rescheduled to 3 March to give the astronauts time to recover.

Finally on their Way!

Once KSC medical director Dr Charles Berry finally cleared the crew for launch, Apollo-9 left the pad exactly on time at 16:00GMT on 3 March. Hopefully the smooth launch impressed Vice President Spiro Agnew (on right in the picture below), who was present in the Launch Control Centre in his new role as Head of the National Space Council, especially as President Nixon has asked his science adviser, Dr Lee Dubridge, to report on possible cost reductions within the US space programme.

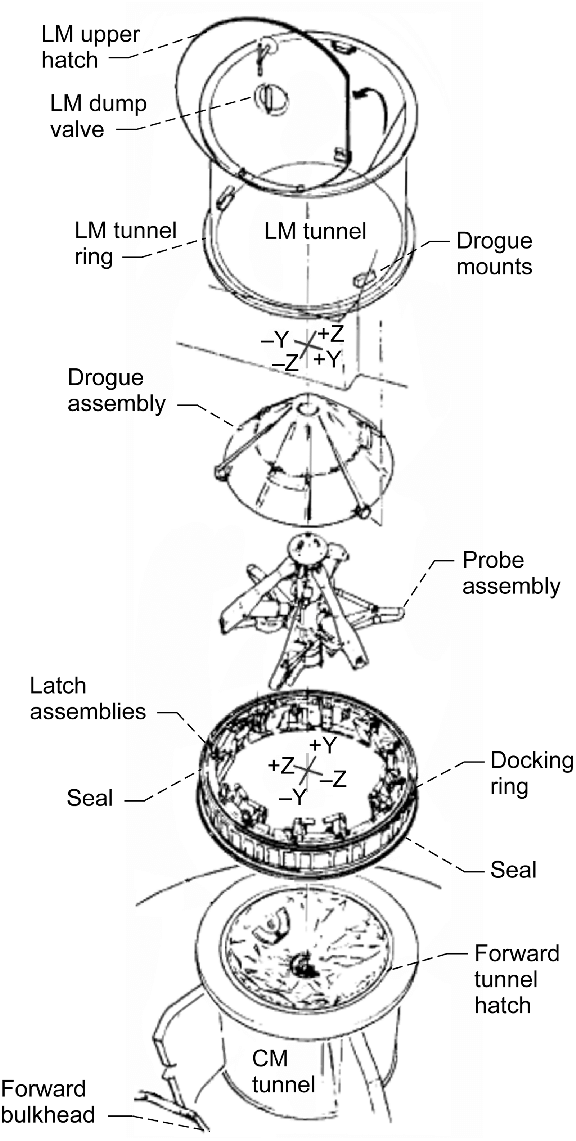

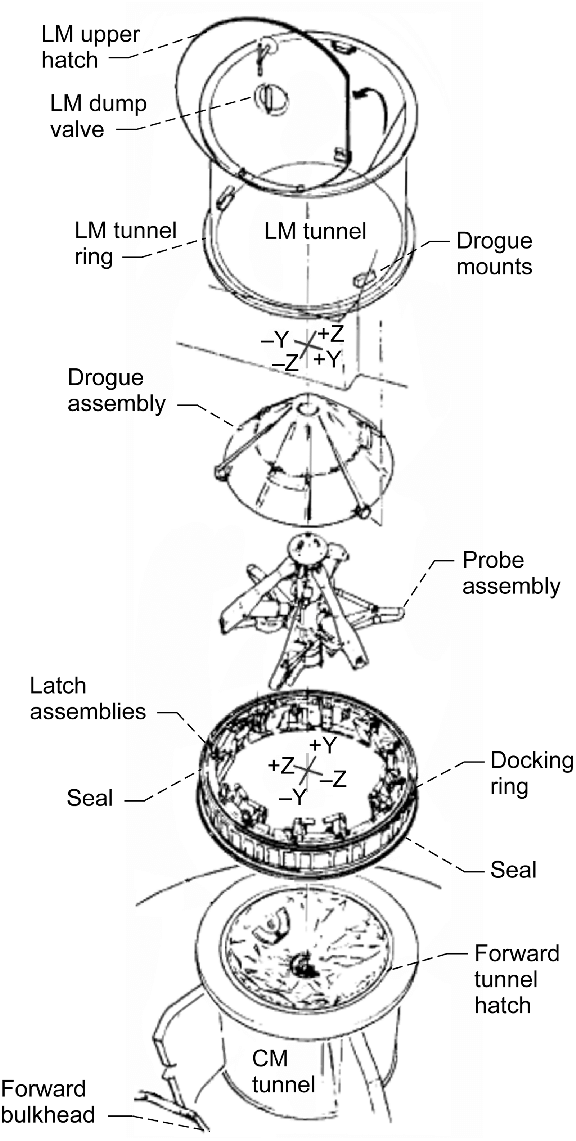

To maximize the chances of accomplishing them, in case any problems forced an early return to Earth, the most critical mission tasks were scheduled for the first five days of the flight. So once the Saturn rocket’s S-IVB third stage and the CSM were safely in orbit, things moved quickly. During the second orbit, CM Pilot Scott turned the CSM and successfully docked with the Lunar Module, nestled in the Spacecraft-Lunar Module Adapter of the S-IVB stage. The linked spacecraft were ejected from the S-IVB, which was then remotely controlled to simulate Trans-Lunar Injection and eventually be sent into a solar orbit.

To maximize the chances of accomplishing them, in case any problems forced an early return to Earth, the most critical mission tasks were scheduled for the first five days of the flight. So once the Saturn rocket’s S-IVB third stage and the CSM were safely in orbit, things moved quickly. During the second orbit, CM Pilot Scott turned the CSM and successfully docked with the Lunar Module, nestled in the Spacecraft-Lunar Module Adapter of the S-IVB stage. The linked spacecraft were ejected from the S-IVB, which was then remotely controlled to simulate Trans-Lunar Injection and eventually be sent into a solar orbit.

Demonstrating that the “probe and drogue” CM-LM docking assembly worked properly is another crucial step towards enabling the future Moon landing. If this system didn’t work, a lunar landing would not be possible.

Once the probe is inserted in the drogue it retracts and pulls the two spacecraft together so that a series of twelve latches locks them tight.

Once the probe is inserted in the drogue it retracts and pulls the two spacecraft together so that a series of twelve latches locks them tight.

Burning Along

Six hours into the mission, the next task was to establish that the docked CSM-LM could be manoeuvred using the Service Module’s Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine. A five-second burn placed the CSM in an orbit of 125 by 145 miles, to improve its orbital lifetime. This short firing demonstrated the CSM guidance and navigation system’s ability to control the burn and showed that the LM’s relatively light structure could withstand thrust, acceleration and vibration.

Following the first sleep period on an Apollo mission during which all three astronauts slept at the same time, Apollo-9’s second day focussed on putting the SPS engine, and the CSM, to the test, through a series of three burns. The first burn, lasting 110 seconds, raised Apollo 9’s orbit to 213 miles and tested the structural dynamics of the docked spacecraft under conditions simulating a lunar mission. This involved gimballing (swivelling) the SPS engine to determine whether the spacecraft’s guidance and navigation autopilot could dampen the induced oscillations. The CSM remained very stable, with the oscillations damped within just five seconds.

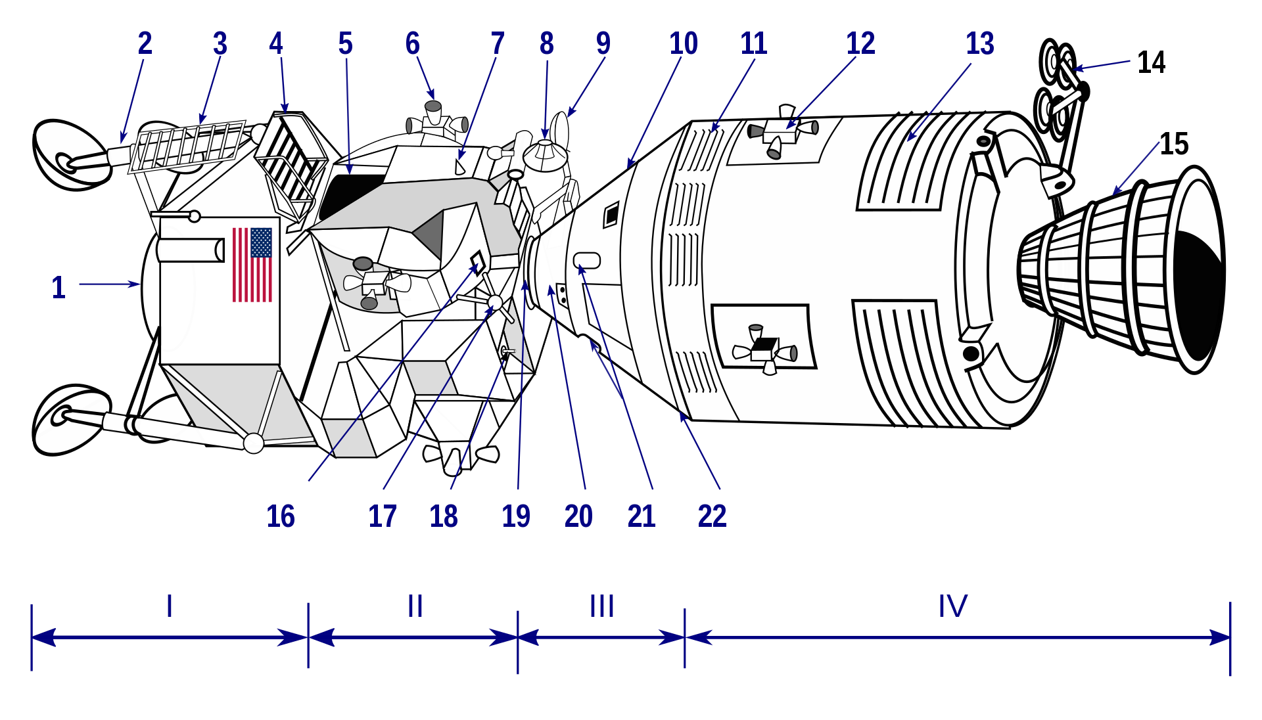

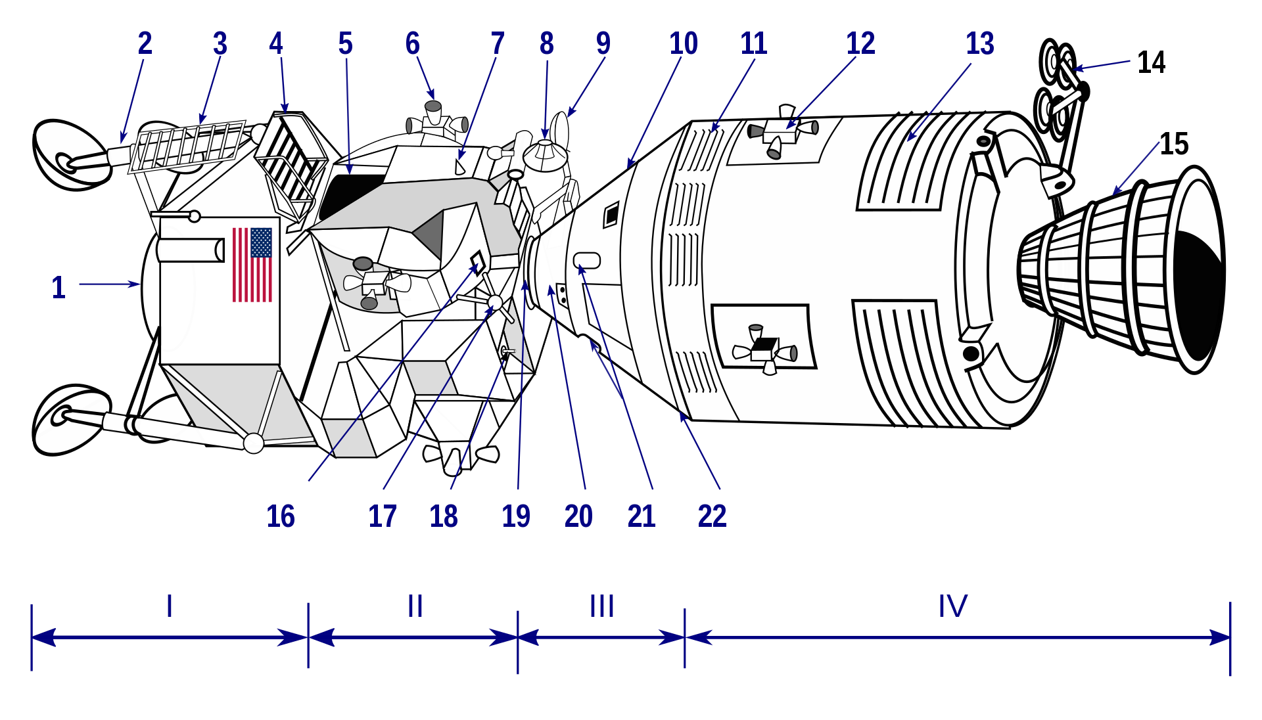

Apollo spacecraft diagram key. CSM (right) and LM (launch configuration) docked. I – Lunar module descent stage; II – Lunar module ascent stage; III – Command module; IV – Service module. 1 LM descent engine skirt; 2 LM landing gear; 3 LM ladder; 4 Egress platform ("porch"); 5 Forward hatch; 6 LM reaction control system quad; 7 S-band inflight antenna (2); 8 Rendezvous radar antenna; 9 S-band steerable antenna; 10 Command Module crew compartment; 11 Electrical power system radiators; 12 SM reaction control system quad; 13 Environmental control system radiator; 14 S-band steerable antenna

Apollo spacecraft diagram key. CSM (right) and LM (launch configuration) docked. I – Lunar module descent stage; II – Lunar module ascent stage; III – Command module; IV – Service module. 1 LM descent engine skirt; 2 LM landing gear; 3 LM ladder; 4 Egress platform ("porch"); 5 Forward hatch; 6 LM reaction control system quad; 7 S-band inflight antenna (2); 8 Rendezvous radar antenna; 9 S-band steerable antenna; 10 Command Module crew compartment; 11 Electrical power system radiators; 12 SM reaction control system quad; 13 Environmental control system radiator; 14 S-band steerable antenna

The second SPS burn lasted 280 seconds, changing the orbit to 126 by 313 miles, while the short third burn, just 28.2 seconds, changed the plane of the spacecraft’s orbit. These orbital changes were designed to position Apollo-9 for better ground tracking and lighting conditions during upcoming mission activities.

Space Sickness Strikes

Entering the LM and checking out its systems was scheduled for flight day three, but planned operations were initially disrupted when space sickness reared its head. Flight surgeons still know little about this condition, which seems to affect some astronauts but not others, and some more than others.

A view inside Command Module Gumdrop

A view inside Command Module Gumdrop

Both Col. McDivitt and Mr. Schweickart were affected, with McDivitt apparently experiencing some mild nausea. Mr. Schweickart, however, vomited in the CM and again later in the LM. When Col. McDivitt contacted the flight surgeons from the LM to report the medical situation, they were less than happy that the earlier incident had not been initially reported, as they could have treated Schweickart’s symptoms sooner.

Opening Up the LM

Although the initial bout of space sickness delayed the start of operations to clear the docking tunnel and access the LM, the astronauts were able to continue with the day’s activities, and both Commander and LM Pilot used the docking tunnel to make the first ever transfer between manned spacecraft without needing to spacewalk. With Lt.-Col. Scott remaining in the CM, and hatches between the Gumdrop and Spider closed, the LM’s communications and life support systems demonstrated that they were operating independently from the CM. Schweickart also deployed Spider’s landing legs (which had been folded for launch) into the position they would assume for landing on the Moon, giving the LM the appearance of its namesake!

A Jumping Spider!

During the nine hours they inhabited Spider, still docked to the CSM, Col. McDivitt and Mr. Schweickart conducted a major test of the Lunar Module’s descent engine, firing it for 367 seconds to simulate the pattern of throttling planned for a descent to the lunar surface. For the final 59 seconds of the burn McDivitt controlled the throttling, varying the thrust from 10 to 40 percent and shutting it off manually, marking the first manual throttling of an engine in space.

This burn, which demonstrated that the LM descent engine could manoeuvre the combined LM-CSM stack, was followed by an additional SPS firing after the LM crew returned to the CM. Together, these burns placed Apollo 9 into an orbit of 142 by 149 miles, ahead of the rendezvous exercises to be performed on day five.

Red Rover (Doesn’t Quite) Cross Over

The step-by-step testing program for Apollo-9 earmarked the fourth day of the mission for a spacewalk to test the reliability of the Apollo EVA suit and the PLSS backpack, necessary because it would be impractical and dangerous for astronauts to move across the Moon’s surface trailing umbilical lines connected to the LM. As the only EVA scheduled before the Moon landing, it was the single opportunity to test the PLSS operationally in space.

Astronaut Schweickart training for his planned EVA

Astronaut Schweickart training for his planned EVA

Using the call sign “Red Rover”, “Rusty” Schweickart was originally scheduled to perform a two-hour EVA to simulate a space rescue technique in the event that a CM-LM docking could not be made, crossing from Spider to Gumdrop. This would have involved him exiting the hatch on the LM and making his way along the outside of the spacecraft to the CM hatch, where Lt.-Col. Scott would be standing by to assist access to the CM. However, the LM Pilot’s bout of space sickness led Col. McDivitt to initially cancel the EVA, due to the flight surgeons’ concerns about the dangers of vomiting in a spacesuit. This also meant the cancellation of a planned TV broadcast of the spacewalk itself, which would have been another first.

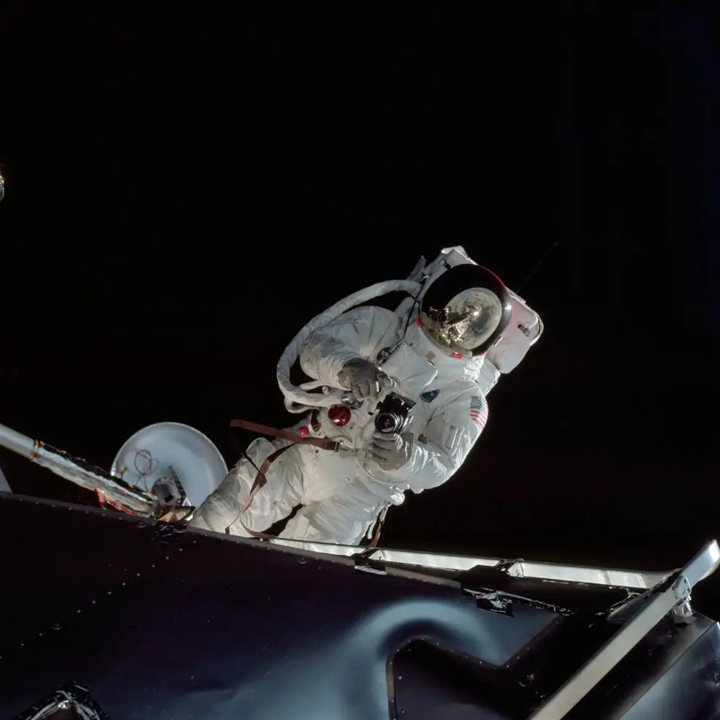

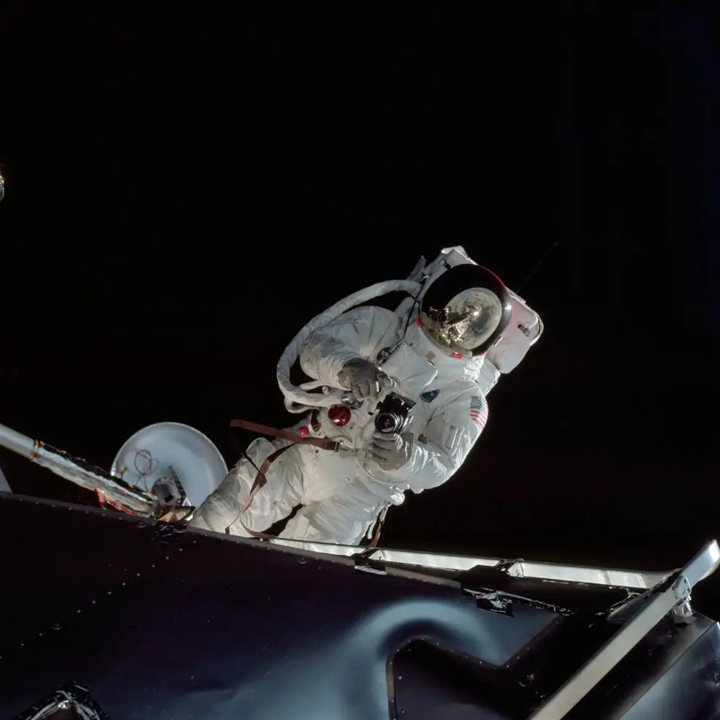

Wearing Golden Slippers

But with Mr. Schweickart feeling somewhat better by day four, a modified short EVA was substituted to enable the EVA equipment test to be carried out. After McDivitt and Schweickart again transferred to Spider, Mr. Schweickert climbed out onto the LM porch for a 37.5-minute EVA, exclaiming “Hey, this is like spectacular” as he stood in the void. For much of this time, the astronaut’s feet were held in gold-coloured restraints, nicknamed the “Golden Slippers”, but he was also able to move around the LM’s exterior using handholds to retrieve some experiments.

At the same time, David Scott, wearing a bright red helmet, made a stand-up EVA in Gumdrop’s hatch and both astronauts photographed each. Scott, too, retrieved experiments from outside the CM. Mr. Schweickart has said that he found moving around easier than it had been in simulations and was confident that he could have completed the spacewalk to the CM had it gone ahead.

The Spider Takes Flight

The key event in Apollo -9’s programme was the undocking and rendezvous tests scheduled for the fifth day of the mission. These manoeuvres would simulate all the activities required for a successful lunar landing and return to lunar orbit. With McDivitt and Schweickart in Spider, and Scott remaining in Gumdrop, the two craft undocked to commence a complex set of manoeuvres and burns of both the LM descent and ascent engines. These tests also carried a new element of danger. The Lunar Module has no ability to return to Earth on its own, since it lacks a heatshield: if something went seriously wrong its crew could end up stranded in space with no way home.

After 45 minutes separated but station keeping, an initial 24.9-second LM descent engine burn placed Spider into a 137 by 167 mile orbit; a second 24.4-second firing circularized the orbit around 154 by 160 miles, approximately 12 miles higher than Gumdrop. Over the next four hours, McDivitt fired the LM’s descent engine at several throttle settings, before lowering Spider’s orbit to begin a two-hour ‘chase’ to catch-up with Gumdrop. The LM descent stage was then jettisoned, and the ascent stage engine fired for the first time, lowering the LM’s orbit still further and placing Spider 75 miles behind and 10 miles below Gumdrop for the rendezvous manoeuvre.

Although it is planned that in future Moon missions, the Command Module pilot will conduct the rendezvous with a returning LM, for Apollo-9 Spider carried out the rendezvous, to demonstrate that the manoeuvre could be performed by either craft. Apart from this difference, the approach and rendezvous hewed as closely as possible to the current plans for lunar missions. Mission Commander McDivitt flew the LM close to Gumdrop, manoeuvring Spider so that CM Pilot Scott could see each side of the vehicle and inspect it for any damage. As he photographed the ascent stage, Scott joked “You’re the biggest, friendliest, funniest looking Spider I’ve ever seen.”

McDivitt then docked to the CM, guided by Scott, as Sun glare was interfering with his vision. Once Spider’s crew returned to Gumdrop, the ascent stage was jettisoned and remotely commanded to fire its engine to fuel depletion, simulating an ascent stage’s climb from the lunar surface. With the approach and rendezvous operation complete, the only major LM system that had not been fully tested during Apollo-9 was the lunar landing radar.

A Bit Camera Shy

Unlike the previous two missions, Apollo 9’s packed programme restricted the television broadcasts made by the astronauts. Spider was equipped with a Westinghouse b/w Lunar Surface Lunar TV Camera, identical to the one taken to be carried to the Moon’s surface on the first landing, as another equipment trial. This low-light “slow scan” camera produced a 320 line, 10 frames per second non-interlaced picture.

Only two broadcasts were from Spider. The first, seven minutes’ long, occurred on day three and showed Mr. Schweickart and Col. McDivitt working in the confined space of the LM. The second broadcast occurred shortly after the end of the EVA on the fourth day, with Spider’s crew still wearing their spacesuits.

The quality of this 15-minute transmission was much better than the previous day, and the crew treated viewers to a scene of Col. McDivitt eating. The camera was then pointed out the LM’s top window to show Gumdrop, then through one of the forward windows to glimpse one of Spider’s attitude control thruster quads and a landing leg. Finally, the view switched back into the cabin to show the LM’s instrument panel and a radiation detector. Once the LM ascent stage was jettisoned, on day five, there were no further broadcasts as the CM did not carry a television camera.

Cruisin' in Orbit

Once the crowded test schedule of the first five days was complete, the second five days of Apollo-9’s flight, intended to test the endurance of the CSM for the total length of a Moon landing mission, were quiet and relaxed by comparison.

Col. McDivitt thanked the Mission Control team for their work during the hectic first half of the mission and jokingly mused: “Might give you the impression that it might work, huh?” The crew sang a belated “Happy Birthdays” to Christopher C. Kraft, Jr., Director of Flight Operations at the Manned Spacecraft Centre, and Apollo 9 crew secretary Charlotte Maltese.

There were additional SPS burns on days six and eight to change the spacecraft’s orbit, with no major activities scheduled for the ninth day, although the astronauts made observations of the Pegasus 3 satellite, passing within 1,000 miles and 700 miles of Apollo 9 during two successive orbits. They also observed the LM ascent stage from about 700 miles away.

Observing the Earth

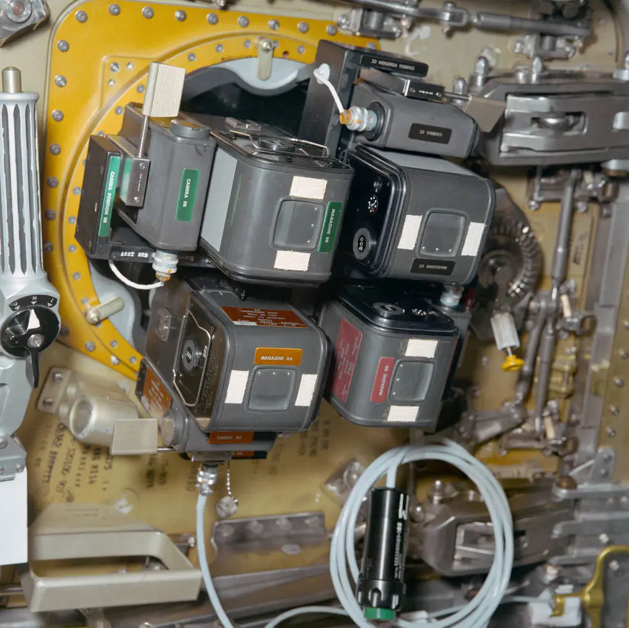

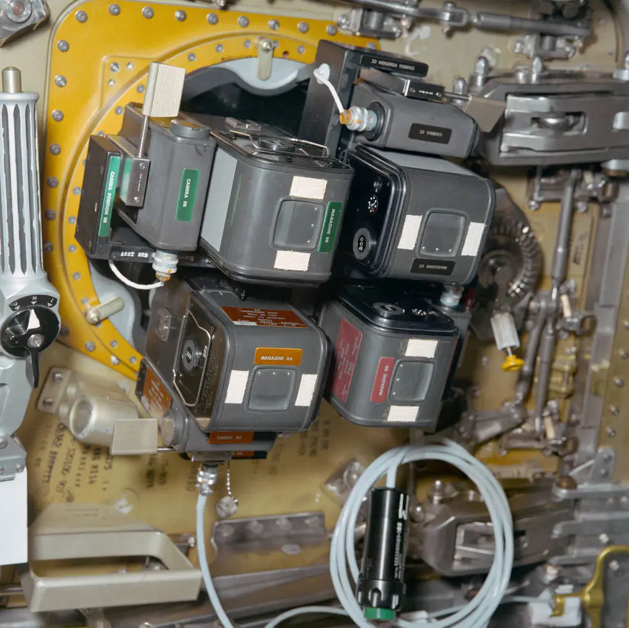

The main activity of the second half of the Apollo-9’s flight was the mission’s only formal scientific investigation, a programme of multi-spectral terrain photography, using four Hasselblad 70 mm cameras pointed out the CM’s round hatch window. This allowed photographs to be taken in four specific wavelengths of the visible and near infrared spectrum simultaneously.

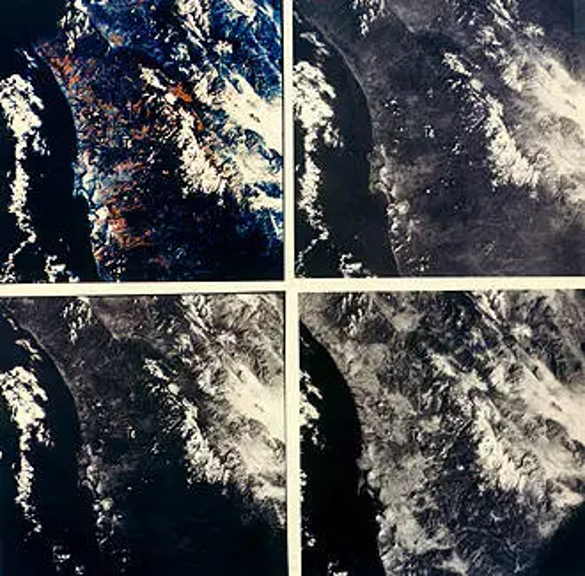

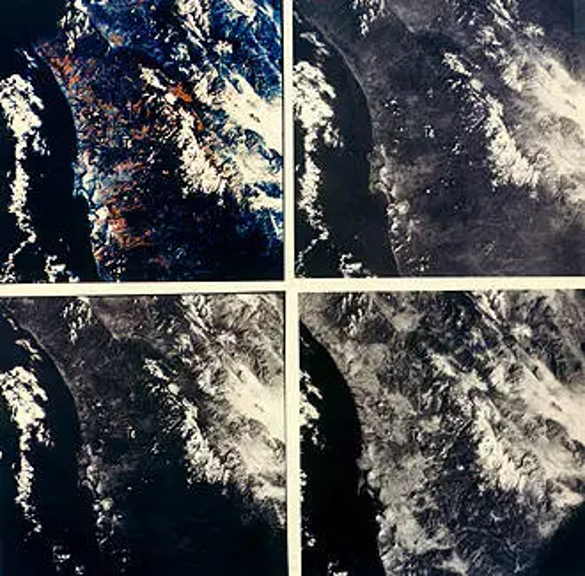

Multi-spectral images. The same view of San Diego and parts of California in four different wavelengths

Multi-spectral images. The same view of San Diego and parts of California in four different wavelengths

This experiment was designed to determine whether multi-spectral photography can be effectively utilised for earth resources programmes such as agriculture, forestry, geology, oceanography, hydrology, and geography. The results will help to refine the instruments for the Earth Resources Technology Satellite (ERTS), due for launch in 1972, Landsat, and techniques for multi-spectral photography to be conducted aboard the Skylab space station in the early 1970s.

Altogether 127 complete four-frame sets of photographs were taken over California, Texas, other areas of the southern United States, Mexico, the Caribbean and the Cape Verde Islands. Astronauts also took more than 1,100 standard Earth observation photographs of targets around the world, using colour and colour infrared film and a handheld Hasselblad camera.

Apollo-9 astronauts' colour photograph of the North Carolina coast and a colour infra-red view of California's Salton Sea

Apollo-9 astronauts' colour photograph of the North Carolina coast and a colour infra-red view of California's Salton Sea

Coming Home

Apollo -9 returned to Earth on 13 March (the 14th for us here in Australia), the tenth day of the mission. Re-entry was delayed by one revolution due to heavy seas in the primary recovery area, but Gumdrop splashed down safely in the Atlantic, within three miles of the recovery ship, the USS Guadalcanal, after a mission totalling 241 hours, 53 seconds – just 10 seconds longer than planned!

On board the recovery ship, the crew were treated to a share of a 350-pound cake baked in their honour. Now safely back in Houston for their flight debriefings, NASA’s attention – and the world’s – is already turning to Apollo-10, due to fly in May to test the LM around the Moon!

Ready for the Next Steps

While Apollo-9 might not have seemed as exciting a mission as Apollo-8’s epic lunar voyage, it was critical because it has simulated in Earth orbit, as far as possible, many of the conditions that the astronauts and their equipment will face when the lunar landing attempt is made. Beyond that first landing and its successors, there is the Apollo Applications Programme, and other developments such as the Skylab manned earth orbiting workshop. Everything that has been learned in space with Apollo-9 will be useful sooner or later in future space activities!

And you can bet we'll be covering each and every one of them here on the Journey…

Apollo-9 view of the Moon

Apollo-9 view of the Moon

![[April 22, 1970] “Houston, We’ve had a Problem Here!” (Apollo-13 emergency in space)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Apollo-13-13-672x372.jpg)

![[March 16, 1969] Flight of the Space Spider (Apollo 9)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Apollo-9-Space-Spider-547x372.png)

![[January 24, 1968] On Track for the Moon (Apollo 5 and Surveyor 7]](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/apollo_5_patch-672x372.jpg)