by Kaye Dee

by Kaye Dee

Last month, I began this article just hours after the crew of

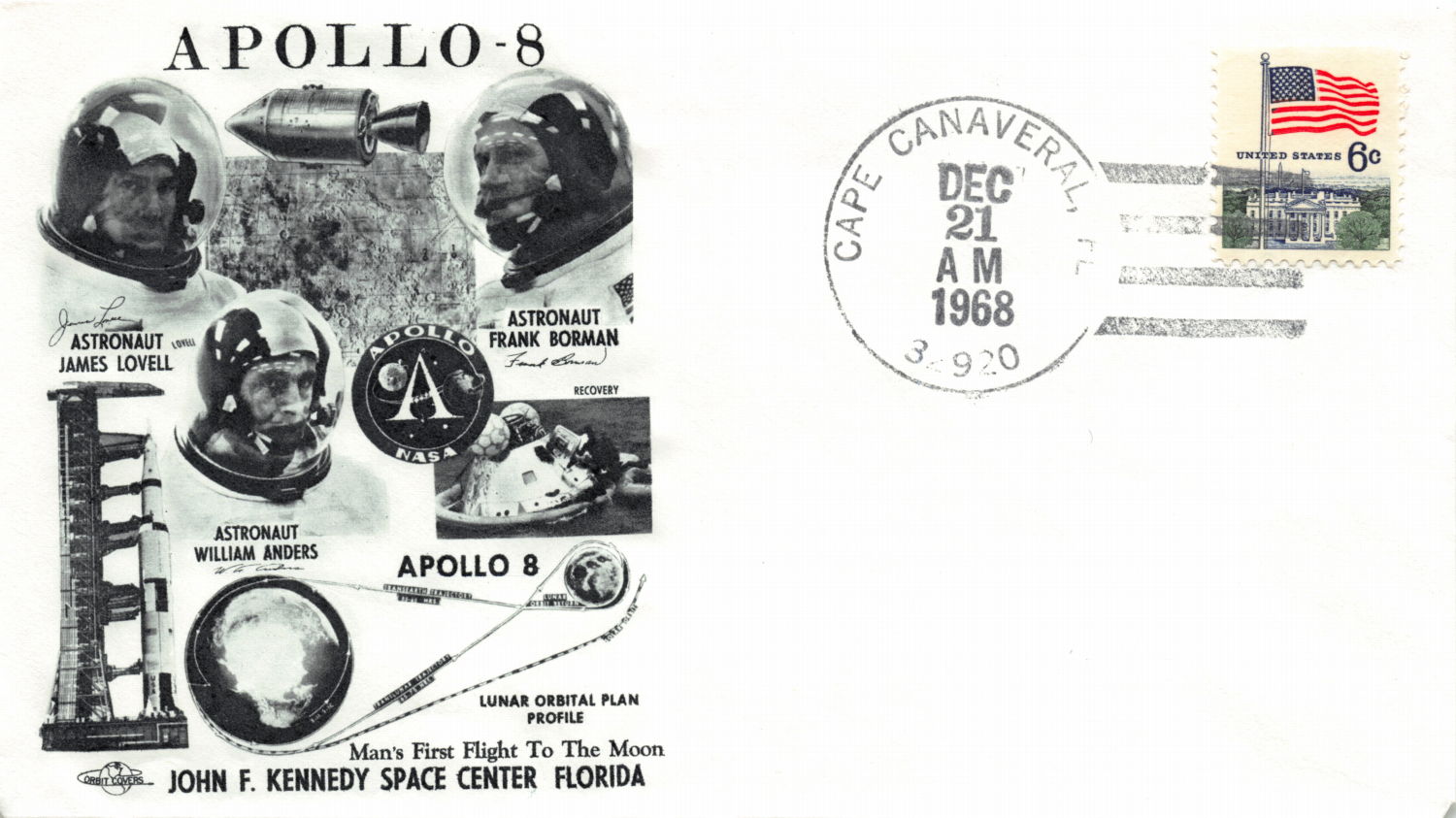

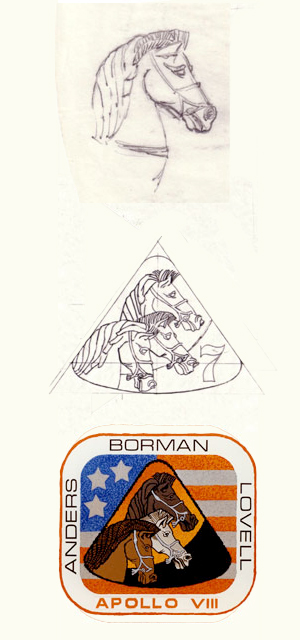

Apollo 8 returned safely to the Earth from their historic mission around the Moon. But even while the mission was in progress, I felt that it might be best to wait to tell the story of the lunar flight in detail, until it could be illustrated with the photographs taken by Col. Borman, Major Anders and Capt. Lovell during their epic journey – images whose breathtaking full-colour views were only hinted at in the low-resolution b/w television broadcasts and the astronauts’ excited descriptions of what they were seeing during the mission.

"Oh my God!" is what Astronaut William Anders said just before he took this awe-inspiring photograph of the Earth rising over the Moon, as seen from lunar orbit. That was my exact response – and yours, too, I expect – on first seeing this incredible sight. I confidently predict that this amazing view will become one of the defining images of the Space Age

"Oh my God!" is what Astronaut William Anders said just before he took this awe-inspiring photograph of the Earth rising over the Moon, as seen from lunar orbit. That was my exact response – and yours, too, I expect – on first seeing this incredible sight. I confidently predict that this amazing view will become one of the defining images of the Space Age

Now that we can see for ourselves the awesome sights that the Apollo 8 crew witnessed, I think I made the right call.

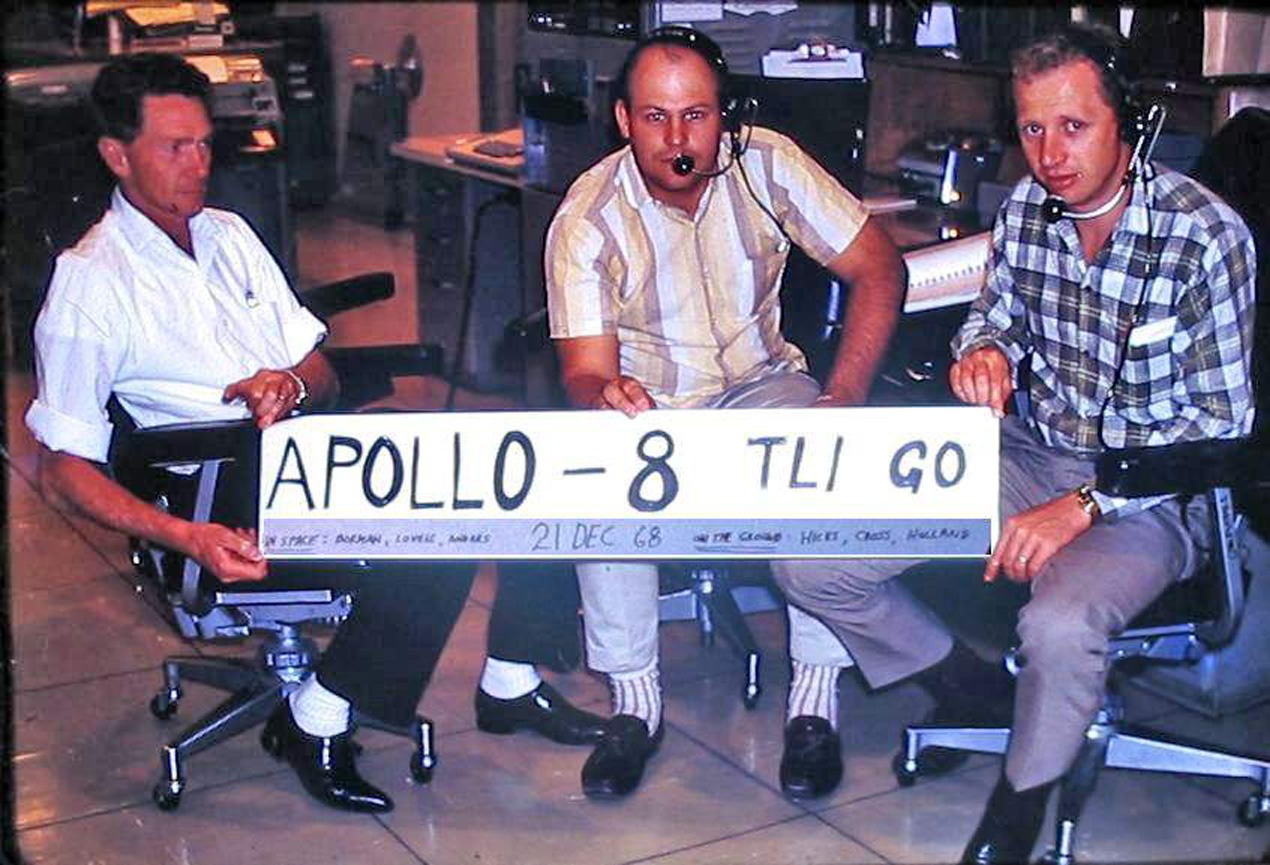

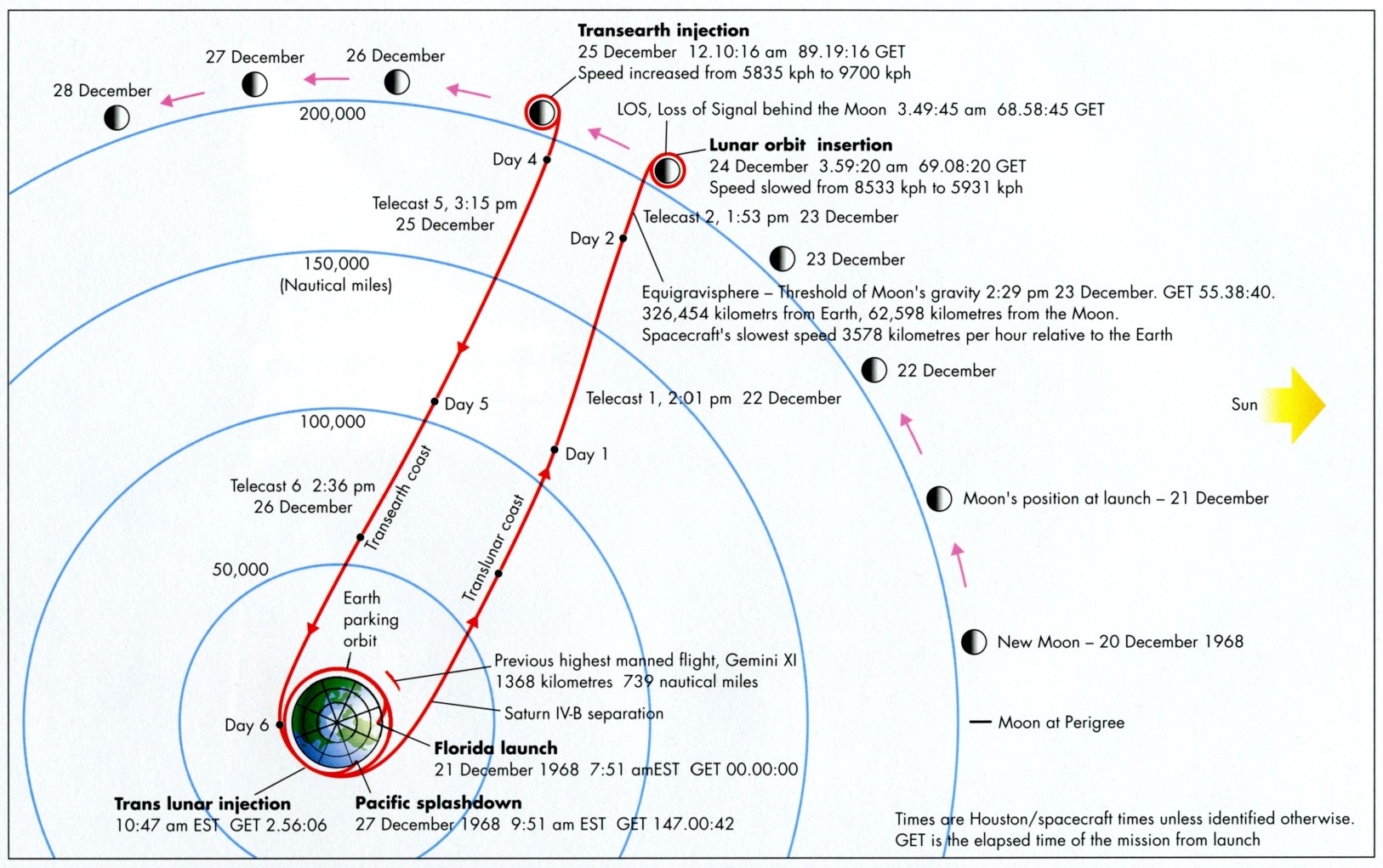

On Course for the Moon

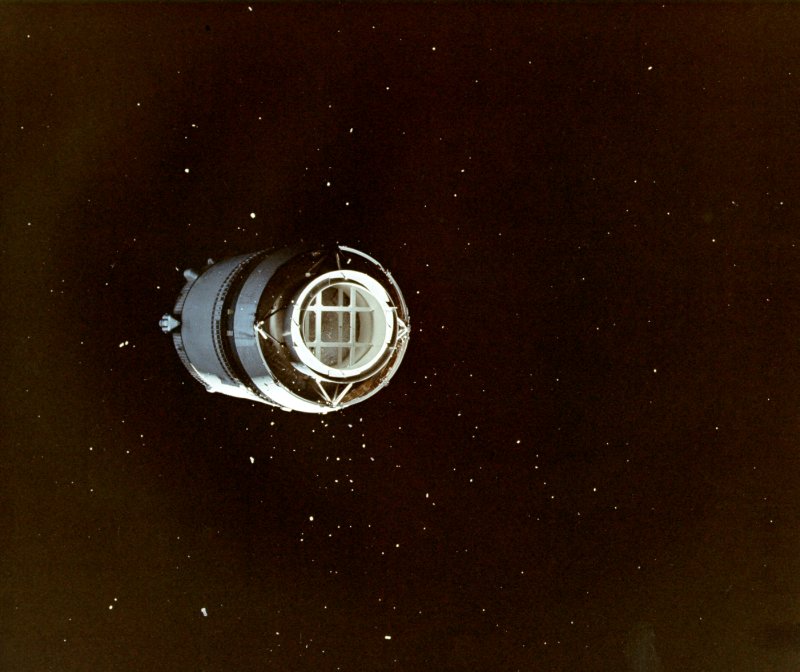

We left Apollo 8 on the way to the Moon, after a successful translunar injection. Just 30 minutes later, the CSM separated from the S-IVB stage, which was ordered to vent its remaining fuel to change the stage’s trajectory. The S-IVB gradually moved away from the CSM and is now in orbit around the Sun.

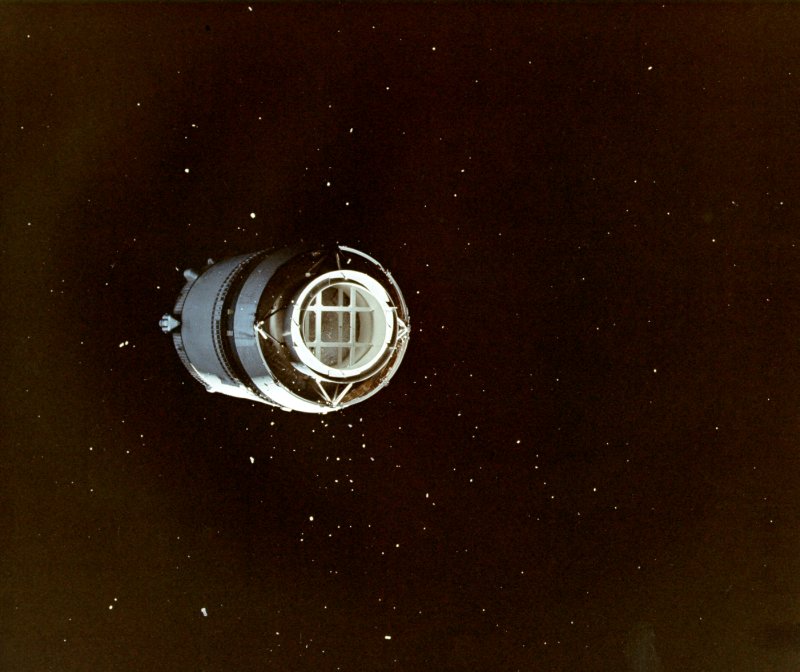

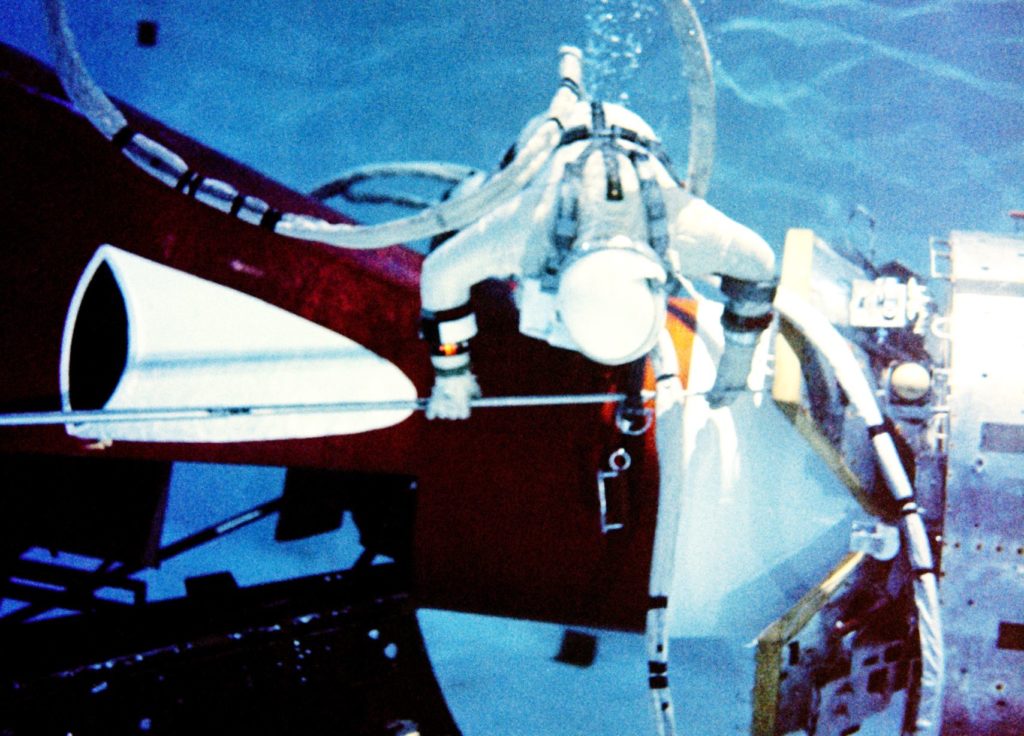

Fuel venting isn't visible in this image of the jettisoned S-IVB stage, but small debris from the separation can be seen floating around it. Although Apollo 8 carried no Lunar Module, this shot shows the LM test article contained in the S-IVB stage

Fuel venting isn't visible in this image of the jettisoned S-IVB stage, but small debris from the separation can be seen floating around it. Although Apollo 8 carried no Lunar Module, this shot shows the LM test article contained in the S-IVB stage

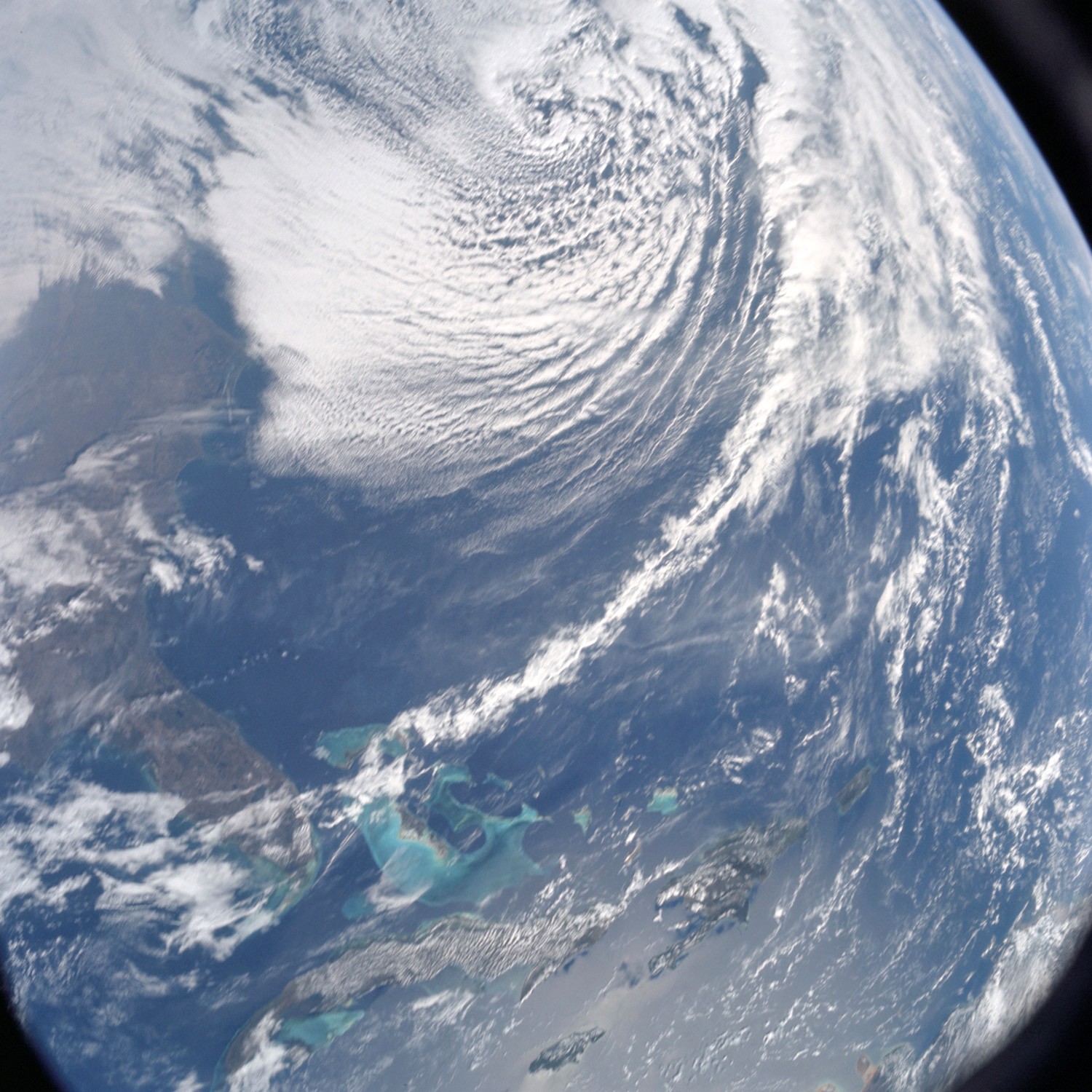

As the crew rotated their spacecraft to view the jettisoned stage, they had their first views of the Earth as they moved away from it—the first time human eyes have been able to view the whole Earth at once. The perspectives of the two images below, taken less than 45 minutes apart, help us gain an impression of how fast the Apollo spacecraft was travelling (around 24,200 mph).

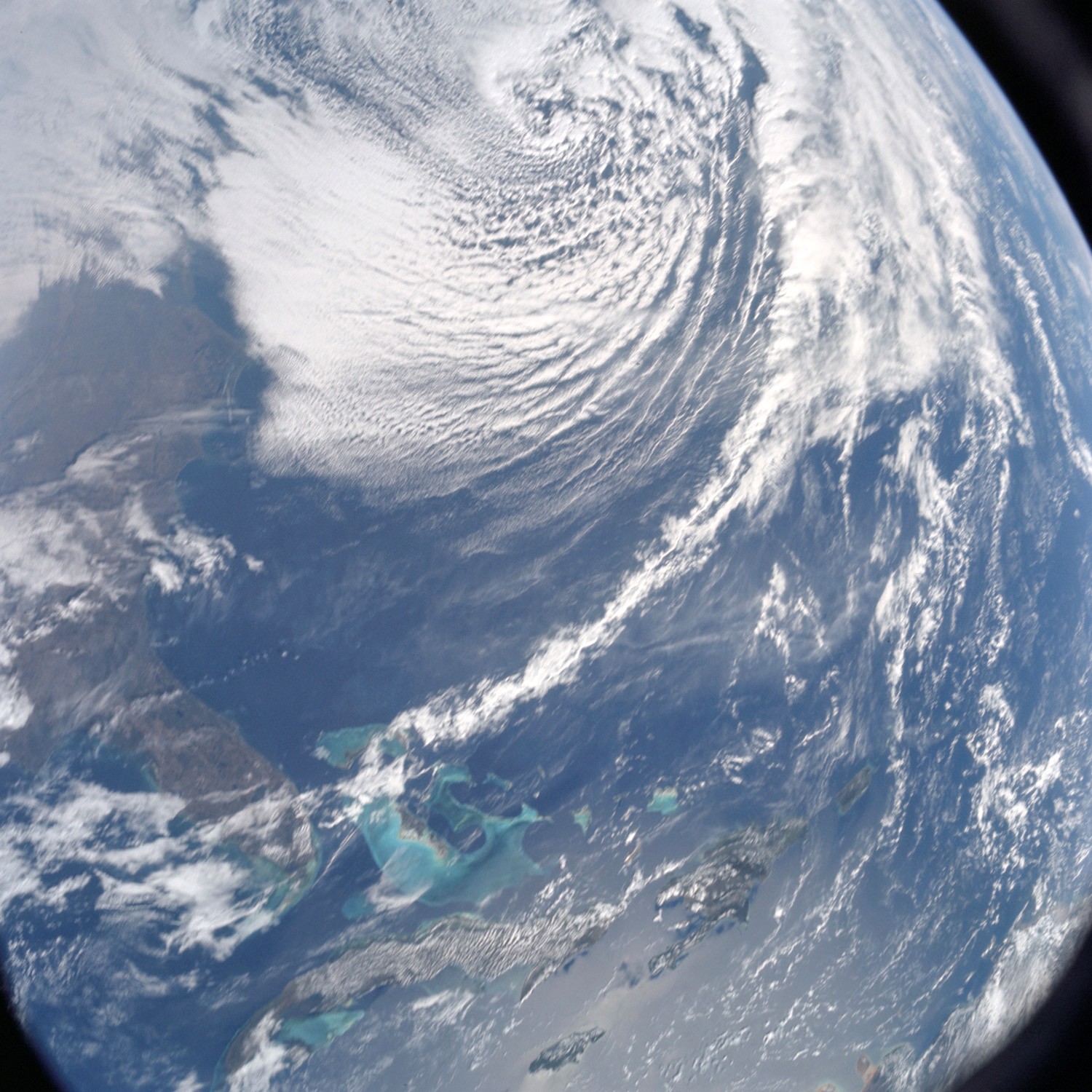

Taken just around the time of TLI, this view from high orbit shows the Florida peninsula, with Cape Kennedy just discernible, and several Caribbean islands

Taken just around the time of TLI, this view from high orbit shows the Florida peninsula, with Cape Kennedy just discernible, and several Caribbean islands

The view of Earth after S-IVB stage separation. From the Americas to west Africa, and from daylight to night, for the first time humans could see their entire planet at a glance!

The view of Earth after S-IVB stage separation. From the Americas to west Africa, and from daylight to night, for the first time humans could see their entire planet at a glance!

Mission Commander Borman has said that he thought this must be how God sees the Earth, while Astronaut Lovell felt he was driving a car into a dark tunnel and was watching the entrance dwindle into a distant speck! But perhaps Major Anders best summed up the awesome view: “How finite the Earth looks. Unlike photographs people see there’s no frame around it. It’s hanging there, the only colour in the black vastness of space, like a dust mote in infinity.”

On the way to the Moon, the CSM adopted the PTC (Passive Thermal Control) or “barbecue” mode tested on

Apollo 7, slowly rotating the spacecraft to keep temperatures evenly distributed over its surface. As the CSM turned, every so often the Earth would appear in one of the windows, making the astronauts aware that they were travelling away from their home planet: it became steadily smaller, until eventually they could cover the whole Earth with a thumb.

Where No Man Has Gone Before

I’m stealing that wonderful

Star Trek catch phrase because soon after the S-IBV jettison, Apollo 8 surpassed the altitude record set by

Gemini 11 in 1966 and was truly setting out into that “new ocean” of space only previously traversed by unmanned probes.

The coast to the Moon was relatively uneventful, with only a few issues arising, including some window fogging, like that experienced on Apollo 7, and a bout of space sickness that it was initially feared might lead to the cancellation of the orbits around the Moon.

Col. Borman reported diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting (none of which you want to have in weightlessness, given the unpleasant consequences!) and both Lovell and Anders also said they did not feel too well. Dr Charles Berry, the medical director at Cape Kennedy, at first feared a 24-hour viral gastro-enteritis that might “play ping-pong”, with the crew re-infecting each other and leaving themselves too weak to carry out their complex tasks correctly. Fortunately, with longer sleep periods, medication and additional rest, the complaint cleared up and did not prove a showstopper for the mission.

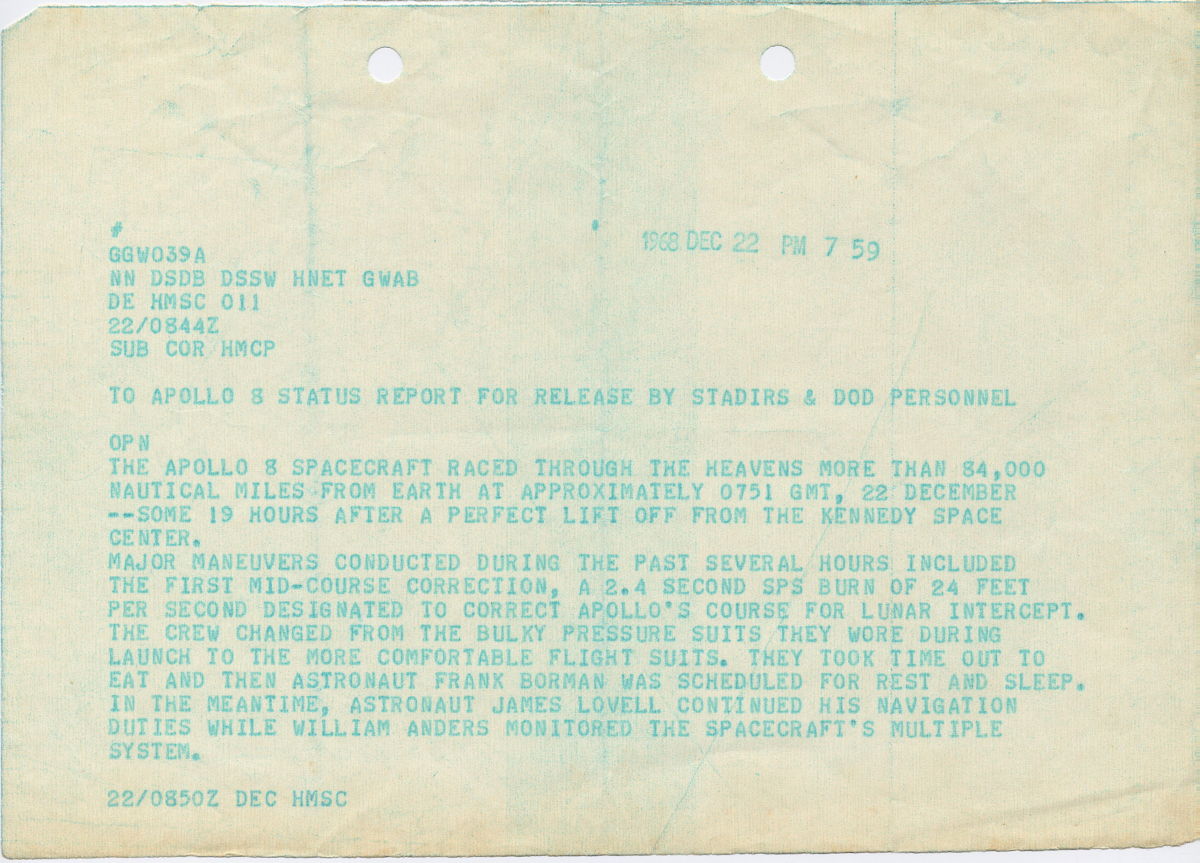

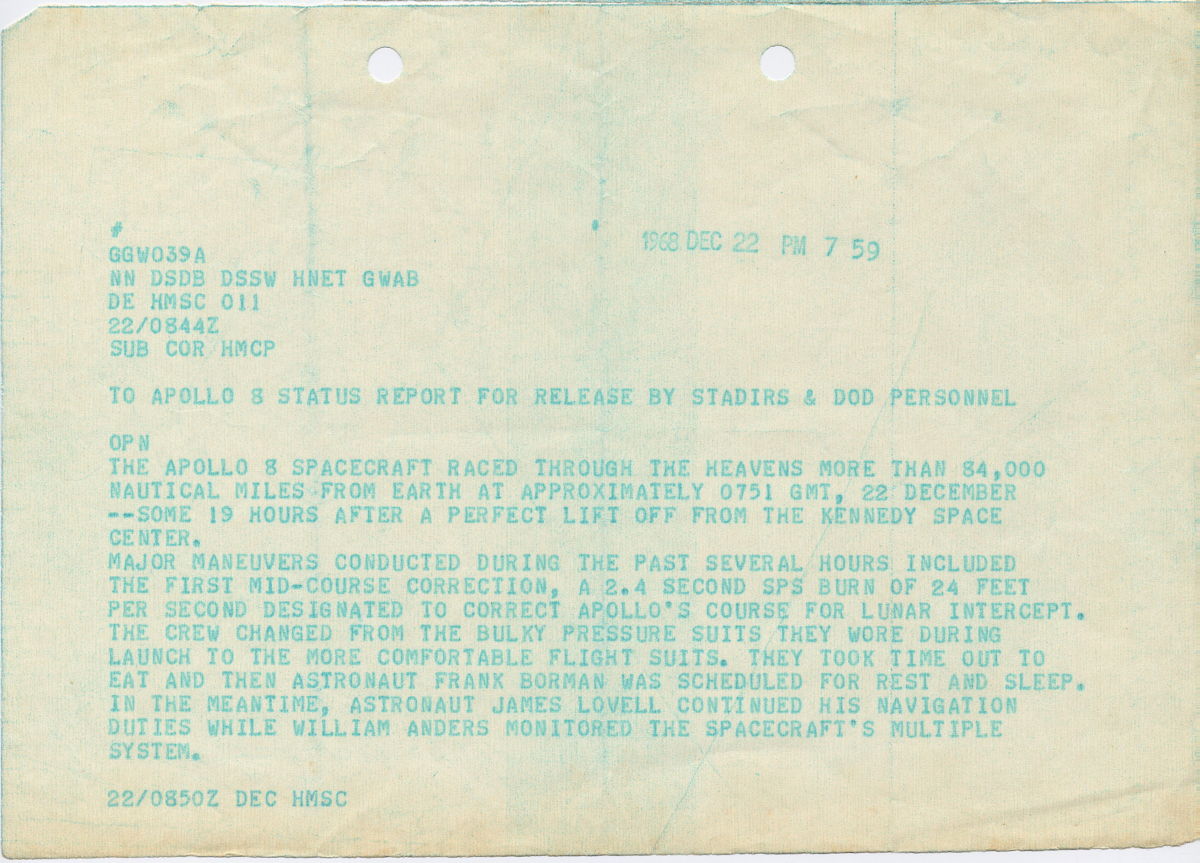

The first mission status report for Apollo 8, sent to the NASA tracking stations around the world, for release to local media. Dated some 19 hours after launch, it outlines some of the activities of the early part of the coast to the Moon

The first mission status report for Apollo 8, sent to the NASA tracking stations around the world, for release to local media. Dated some 19 hours after launch, it outlines some of the activities of the early part of the coast to the Moon

A slight course correction saw the large SPS motor fired for the first time, providing a check that the spacecraft’s main propulsion system was working correctly. Had there been any problems, Apollo 8 would not have gone into lunar orbit, but looped around the Moon to return to Earth.

Out of this World Broadcasts

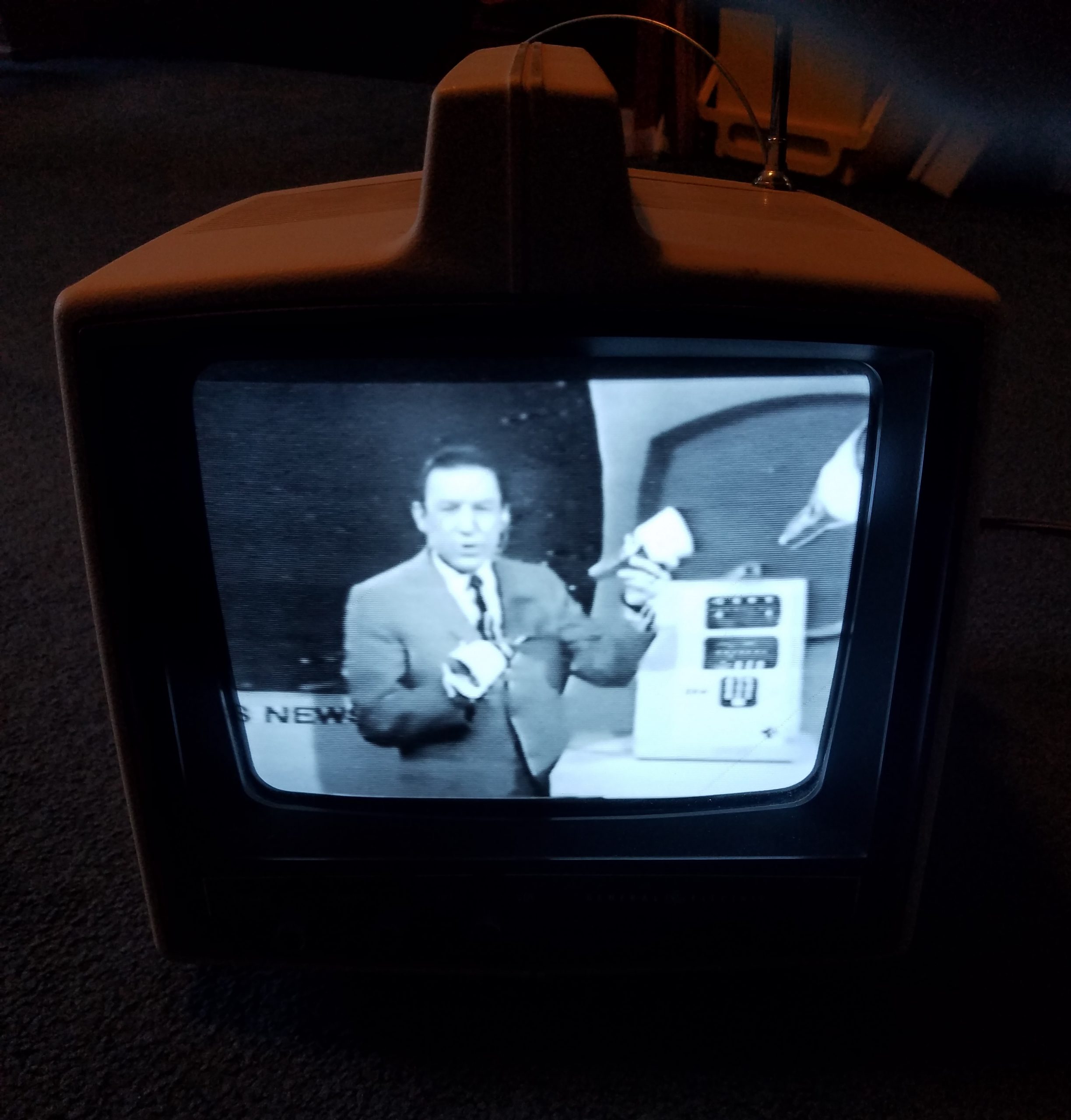

About halfway to the Moon, at 31 hours and 10 minutes after launch, the astronauts conducted the first of six television broadcasts during the mission. Like Mission Commander Schirra on Apollo 7, Borman was apparently not in favour of television broadcasts – holding that the weight of the camera was better used for other equipment and additional food supplies – but was overruled by NASA.

For this first deep space show, the approach was light-hearted, with the opening scenes from the spacecraft showing Capt. Lovell upside down in the lower equipment bay making jokes about preparing lunch. Bill Anders played with his weightless toothbrush, with quips from Frank Borman about his crewmate cleaning his teeth regularly. Jim Lovell sent birthday wishes to his mother. The crew tried to show us the Earth through the one of the CM windows, but without a viewing monitor, they couldn't quite capture it in their camera's field of view.

Astronaut Anders shows us his toothbrush (top) and Jim Lovell wishes his mother "Happy Birthday" (bottom) during Apollo 8's first deep space broadcast

Astronaut Anders shows us his toothbrush (top) and Jim Lovell wishes his mother "Happy Birthday" (bottom) during Apollo 8's first deep space broadcast

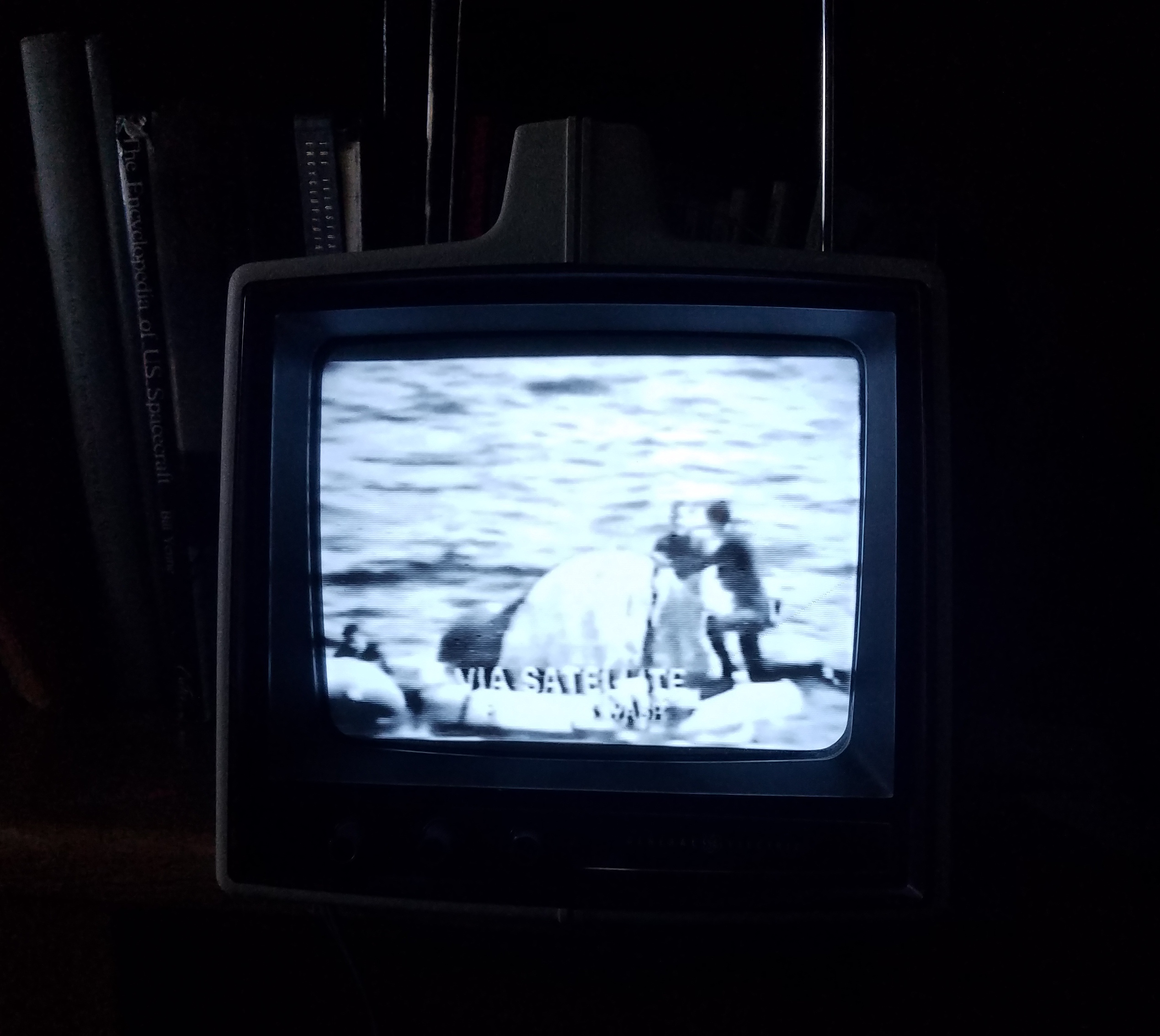

The astronauts were disappointed to find their view of the approaching Moon was washed out by the Sun’s powerful glare. It should have been a spectacular sight to see its cratered surface increasing in size and detail as they closed in, but they were not able to get good views of the Moon until they were relatively close. However, during their second television broadcast, 55 hours into the mission, the crew of Apollo 8 were finally able to capture the Earth through one of their spacecraft's windows.

While the resolution of the image may not have been very high, this first ever live view of our planet from 180,000 miles out in space was yet another step in science fiction being made into reality! During the 25 minute broadcast, there was a delightful exchange between Lovell and Anders, with Capcom Michael Collins in Houston, wondering what a traveller from another planet would think of the view of Earth from that distance, and whether they would imagine it was inhabited.

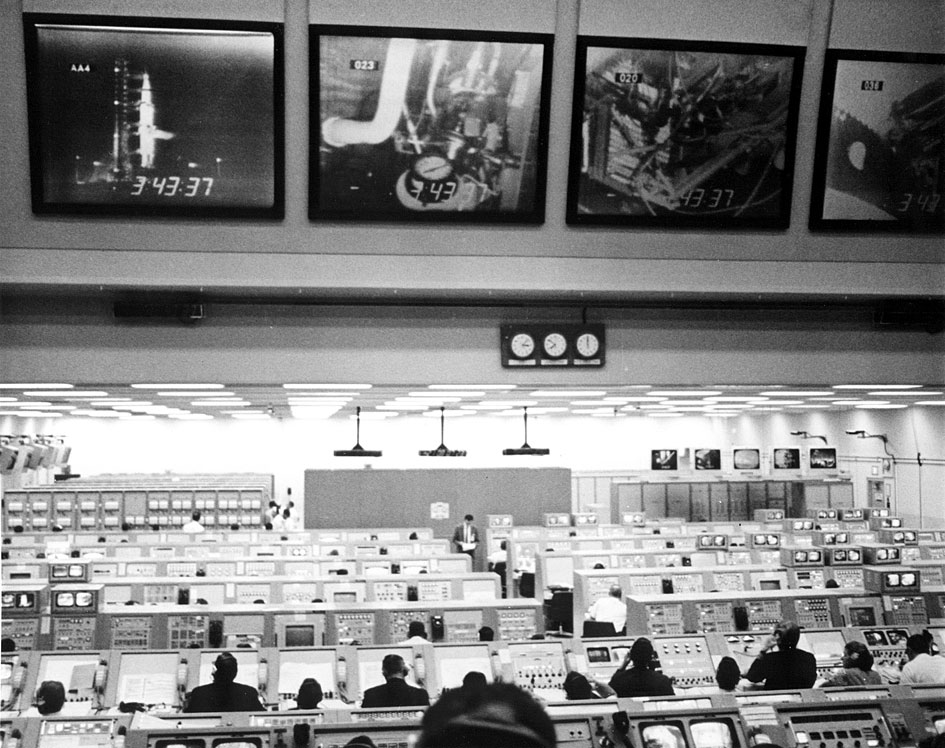

The Apollo 8 second broadcast view of the Earth as we saw it on television (above) and how Capcom Collins saw it on his monitors in Mission Control (bottom). Would alien visitors to our solar system think anyone lived there?

The Apollo 8 second broadcast view of the Earth as we saw it on television (above) and how Capcom Collins saw it on his monitors in Mission Control (bottom). Would alien visitors to our solar system think anyone lived there?

Moving into the Moon's Sphere of Influence

Moving into the Moon's Sphere of Influence

Shortly after their second broadcast, Borman, Lovell and Anders became the first humans to leave the Earth’s sphere of gravitational influence: they were 202,825 miles from Earth and 38,897 miles from the Moon. This move into the lunar gravity field meant that soon a decision would need to be made as to whether or not Apollo 8 would go into lunar orbit, or loop around the Moon and return directly to the Earth. So concerned was Col. Borman about any trajectory perturbations that would preclude the spacecraft from achieving lunar orbit that he even checked with Houston before dumping urine overboard!

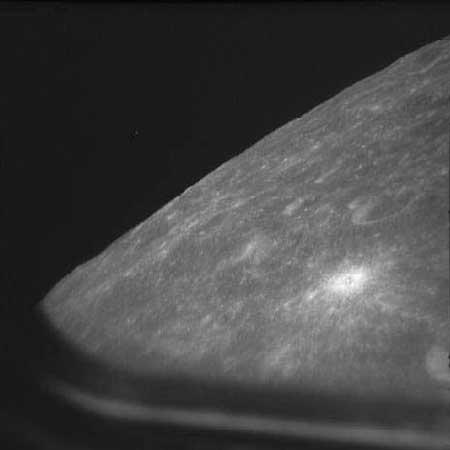

A view of the Moon, finally visible as Apollo 8 approached and prepared to go into orbit

A view of the Moon, finally visible as Apollo 8 approached and prepared to go into orbit

Then came the moment to go behind the Moon – and the decision whether or not to orbit. “Apollo 8 this is Houston,” Capcom Jerry Carr called. “At 68 hours 4 minutes you are Go for LOI (Lunar Orbit Insertion).” But the necessary SPS engine burn to change the CSM's trajectory from "free return" to lunar orbit had to take place above the far side of the Moon, where Apollo 8 would be completely out of contact with the Earth.

On 24 December, just on 69 hours after lift-off, Apollo 8 slipped behind the Moon. Col. Borman was so impressed with the exact predicted timing of the loss of communication with the Earth that he joked about whether the Manned Space Flight Network had turned off its transmitters! But, in truth, the situation was very tense, as all the astronauts and Mission Control could do was wait and hope that all would go well with the burn to put Apollo 8 into lunar orbit. The Service Propulsion System engine had to work perfectly, or the astronauts would be in serious trouble.

The Manned Space Flight Network station at Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra, was tracking Apollo 8 as it went behind the Moon and received the first signals as it re-emerged, safely in lunar orbit

The Manned Space Flight Network station at Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra, was tracking Apollo 8 as it went behind the Moon and received the first signals as it re-emerged, safely in lunar orbit

Fortunately, Apollo 8 slowed in response to the 4 minute 6.9 second burn – “Longest four minutes I’ve ever spent,” according to Capt. Lovell. This put the spacecraft into a 194 x by 69 mile orbit around the Moon after a Trans-Lunar Coast of 66 hours 16 minutes and 22 seconds.

Round (and Round) the Moon

Safely in orbit, the plan was for Apollo 8 to make 10 orbits around the Moon over a twenty hour period. Even though the far side of the Moon was first seen as far back as 1959, by the USSR's

Luna 3, the first order of business was for the crew to observe the far side surface for themselves. The three astronauts were stunned by the crater-pitted Moonscape sliding below them, revealing a tortured terrain so unlike the familiar face of the Moon. Out of contact with the Earth, totally isolated from home, Borman, Lovell and Anders forgot their mission for a few moments to press their faces against the CM windows and soak up the sights!

The astronauts were not exactly impressed with the gritty, grey, plaster-like surface they observed as they orbited the Moon. Col. Borman described it as as “[looking] like the burned-out ashes of a barbecue,” while Capt. Lovell said “It’s like a sand pile my kids have been playing in for a long time. It’s all beat up with no definition. Just a lot of bumps and holes.” Major Anders felt the surface looked "whitish-grey, like dirty beach sand with lots of footprints in it.”

Jim Lovell's "sand pile" on the Moon!

Jim Lovell's "sand pile" on the Moon!

Back on Earth Mission Control held its breath, waiting for Apollo 8 to re-emerge from behind the Moon and confirm that the SPS engine had performed as planned. But once the crew were back in contact with Earth, a packed routine of surface observations was quickly established: these images comprise the bulk of the more than 800 70 mm still photographs and 700 feet of 16 mm movie film that the astronauts took during the mission. Among their tasks, the astronauts observed Earthshine (the light reflecting from Earth shining on the dark face of the Moon) – which they found provided enough light to see surface features clearly – and took detailed photographs of the area within the Sea of Tranquillity where, all going to plan in the next few months, the Apollo 11 mission will make the first manned lunar landing.

On the second orbit, Apollo 8's 12 minute long third television broadcast was almost entirely dedicated to allowing us back on Earth to see the astronauts' view of the Moon. Even when it was difficult to see much detail in the views of the lunar surface passing below the spacecraft, this broadcast made us, as it were, part of the mission.

View of the Moon's surface during the third Apollo 8 television broadcast

Earthrise

View of the Moon's surface during the third Apollo 8 television broadcast

Earthrise

Busy with lunar surface observations, during their first three orbits the Apollo 8 crew failed to even notice an incredible sight. It was not until their fourth orbit that the astronauts experienced perhaps the most sublime view provided by space exploration to date – the vision of the Earth rising above the lunar horizon!

On this fourth orbit, a navigation sighting meant that the CSM was rolled to look outwards into space instead of down towards the Moon's surface. As the lunar horizon came into view, the astronauts witnessed a magnificent sight – the cloud-mottled blue orb of the Earth swimming into their view.

Awestruck, they scrambled so quicky to capture the vision that no-one is quite sure now who took which picture, although it seems that Col. Borman may have snapped the first black and white photograph, and Bill Anders a number of breathtaking colour images of the Earthrise.

Apollo 8's Earthrise images are usually published oriented with the lunar horizon at the bottom, as that is how we are used to seeing the Moon rising over the horizon on Earth. But the orientation of astronauts' orbit meant that they actually saw the Earth appearing to rise 'sideways', as seen in this original version of Major Anders' photograph

Apollo 8's Earthrise images are usually published oriented with the lunar horizon at the bottom, as that is how we are used to seeing the Moon rising over the horizon on Earth. But the orientation of astronauts' orbit meant that they actually saw the Earth appearing to rise 'sideways', as seen in this original version of Major Anders' photograph

While Apollo 8 isn't the first space mission to capture the vista of the Earth rising over the Moon – that honour goes to

Lunar Orbiter 1 – the impact of the superior quality and colour of the astronaut's photographs is profoundly inspiring, and Major Anders' evocative Earthrise image is already well on its way to becoming the most reproduced image of the Space Age so far.

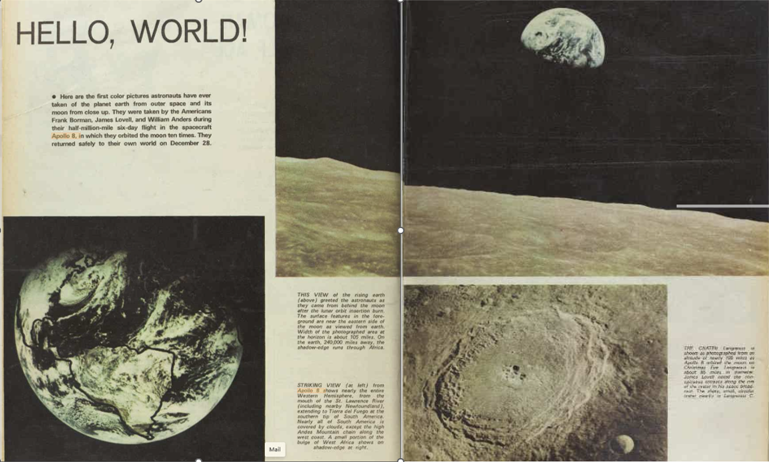

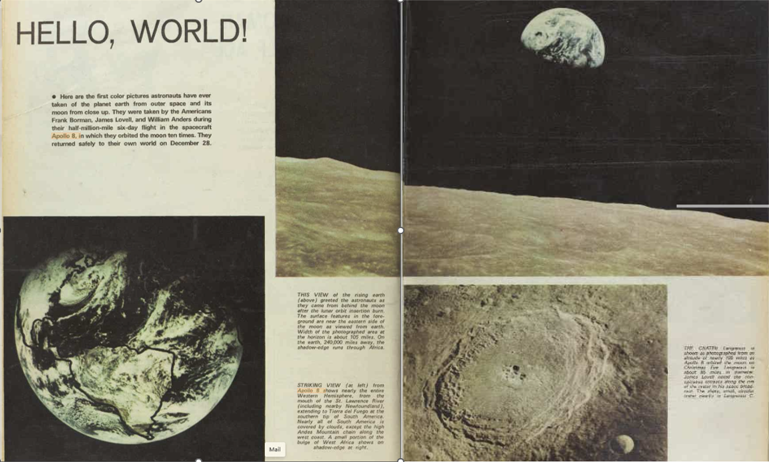

This spread from the 15 January issue of the Australian Women's Weekly is just one example of thousands of magazine and newspaper articles already featuring the Earthrise photograph and Apollo 8's other amazing pictures

This spread from the 15 January issue of the Australian Women's Weekly is just one example of thousands of magazine and newspaper articles already featuring the Earthrise photograph and Apollo 8's other amazing pictures

I'm so moved by the Earthrise image that I find it hard to put all my feelings into words, but perhaps those I quoted above from Astronaut Anders go some way to expressing them, as do Captain Lovell's similar thoughts on the view: “The vastness up here of the Moon is awe inspiring. It makes you realize just what you have back there on Earth. The Earth from here is a grand oasis in the blackness of space.”

This view of the living Earth in the immensity of the Cosmos truly brings home to us the fragility and isolation of our home planet and its finite resources, providing the visual encapsulation of the expression "Spaceship Earth" popularised over the past few years by

Buckminster Fuller among others. The environmental movement needs to utilise the power of this image to help encourage us all to be better stewards of the Earth and preserve our environment, so necessary for our survival, for future generations.

"Something Appropriate"

Acutely aware of the historic nature of the Apollo 8 mission, NASA wanted the astronauts to “do something appropriate” for their fourth television broadcast. Due to occur on the ninth lunar orbit, this finale to Apollo 8’s time at the Moon was scheduled for late evening on Christmas Eve in the United States (comfortably at lunchtime on Christmas day for us here in Australia). The program was to be transmitted via satellite to 64 countries (where it was seen or heard by an estimated one billion people!), so it was a major global event, comparable to 1967’s

Our World broadcast.

What would be appropriate for such an international audience? The astronauts wanted to present something spiritually significant and memorable, but not overtly religious, that would be relevant at Christmas to both Christians and the millions of non-Christians who would be tuning into the broadcast. It seems that the wife of a journalist (I’m sorry, I don’t know her name) suggested that they read from the opening of the Book of Genesis, which has meaning for many of the world’s religions and expresses concepts relevant to many other faiths. The crew liked this idea and planned to incorporate it into their broadcast.

A view of the Moon seen by the audience on Earth while the crew of Apollo 8 read from the Book of Genesis

A view of the Moon seen by the audience on Earth while the crew of Apollo 8 read from the Book of Genesis

The fourth telecast from Apollo 8 began with the astronauts talking about their impressions of the Moon and the experience of being in lunar orbit. Following some views of the lunar terrain, described by the astronauts as they passed over, Major Anders said that the crew had a message for everyone on Earth. In turn, Anders, then Capt. Lovell and finally Col. Borman read the first 10 verses of Genesis, as we watched the Moon’s surface pass by, with a view through one of the CM windows. Borman then ended the broadcast with “And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas and God bless all of you – all of you on the good Earth.” I watched this transmission at lunch with my sister’s family: it left us all profoundly moved.

Families around the world gathered on Christmas Eve/Christmas Day (depending on where you were!) to watch Apollo 8's broadcast

Set Course for Earth

Families around the world gathered on Christmas Eve/Christmas Day (depending on where you were!) to watch Apollo 8's broadcast

Set Course for Earth

Two and a half hours after the end of the fourth television broadcast, on Apollo 8’s tenth lunar orbit, it was time to perform the trans-Earth injection (TEI). This manoeuvre was even more critical than the one which had brought the CSM into orbit around the Moon: if the SPS engine failed to ignite, the crew would be stranded in lunar orbit. Like the previous SPS burn, this critical firing had to occur above the far side of the Moon, once again out of contact with the Earth. Despite all the telemetry indicating that the SPS was in good shape, tension was high while the spacecraft was behind the Moon, but the burn was perfect and Apollo 8 re-emerged exactly on schedule 89 hours, 28 minutes, and 39 seconds after launch.

It was Christmas Day, and when voice contact was restored with Houston, Lovell announced to the world, “Please be informed, there is a Santa Claus” – apparently for the benefit of one his sons, who had asked before the flight if his father would see Santa while visiting the Moon.

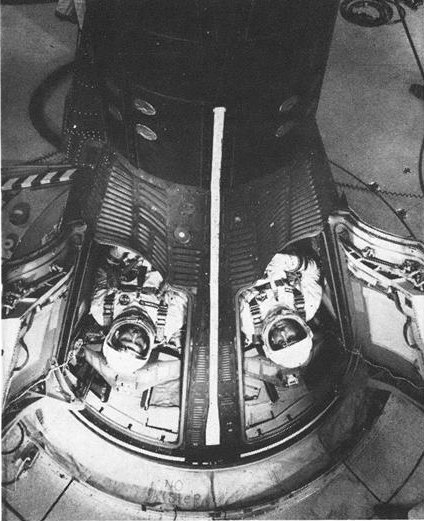

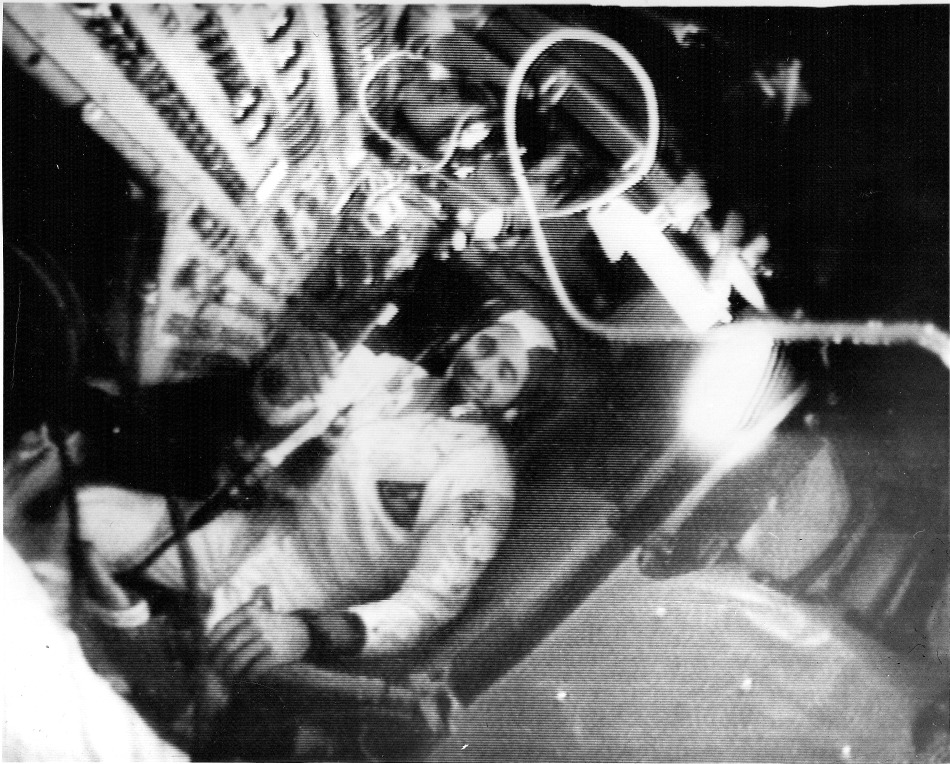

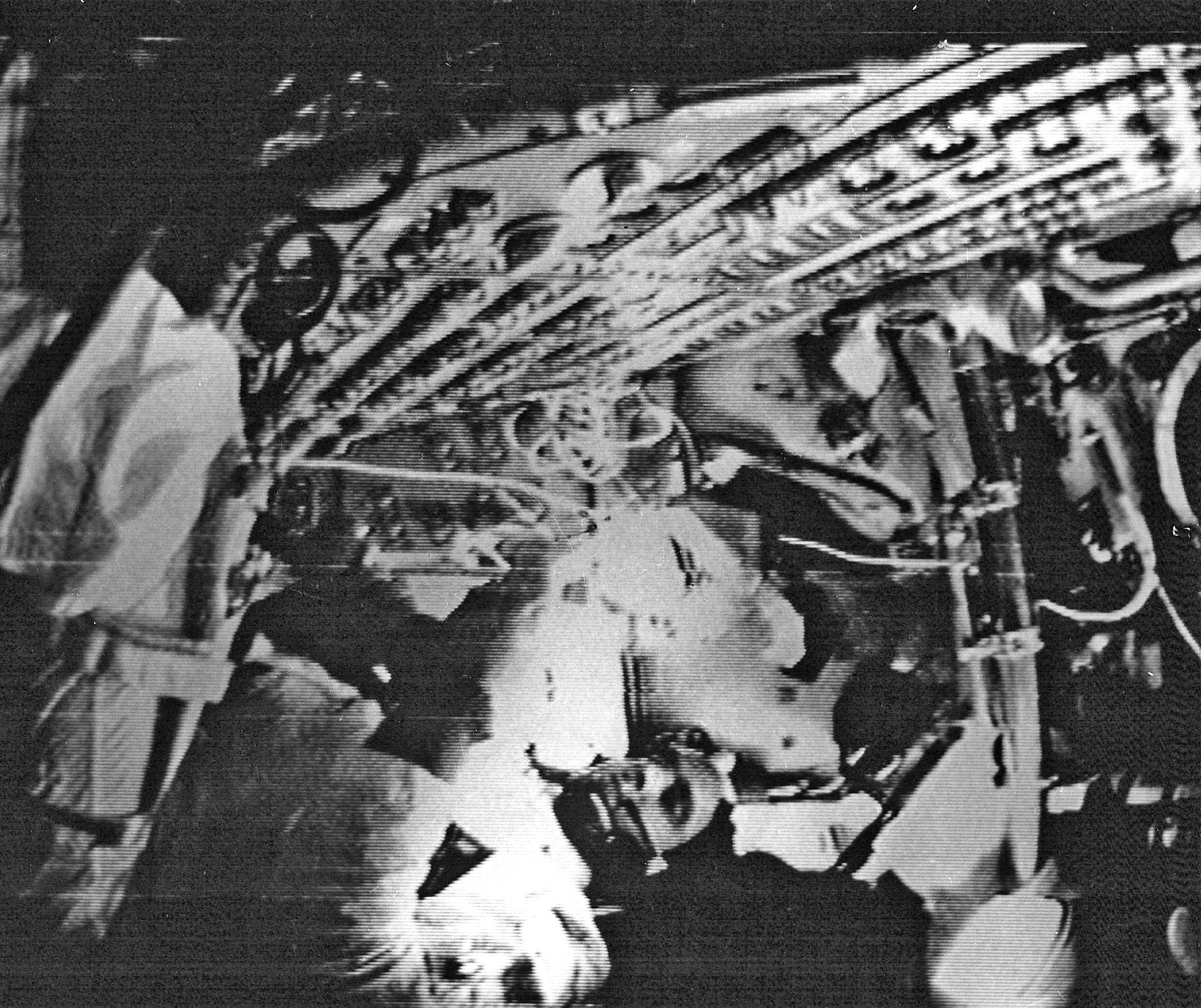

A view inside the Command Module, during the fifth Apollo 8 television broadcast

A view inside the Command Module, during the fifth Apollo 8 television broadcast

At about 100 hours and 48 minutes after launch, Apollo 8 crossed back into the Earth’s sphere of influence and began gradually speeding up. After the astronauts carried out the only required midcourse correction at 104 hours into the mission, the crew had some time to relax before their fifth television broadcast. During this 10 minute transmission, they gave viewers a tour of the spacecraft, showing how they lived in the weightless environment.

An image from the fifth broadcast taken directly from a monitor at the Honeysuckle Creek tracking station. It shows Bill Anders demostrating how to prepare a meal

A Christmas Dinner to Remember

An image from the fifth broadcast taken directly from a monitor at the Honeysuckle Creek tracking station. It shows Bill Anders demostrating how to prepare a meal

A Christmas Dinner to Remember

After the broadcast, the crew were finally free to tuck into their Christmas dinner – and found a surprise in their food locker. It was a specially packed Christmas dinner wrapped in foil and decorated with red and green ribbons! A gift from Director of Flight Crew Operations Deke Slayton, the special meal included dehydrated grape drink, cranberry-applesauce, and coffee, as well as a new “wetpack” containing turkey and gravy. Also hidden with the surprise dinner, the astronauts found small presents from their wives.

Slayton also included three miniature bottles of brandy with the meal, although Borman decided that they should be saved until after splashdown!

Slayton also included three miniature bottles of brandy with the meal, although Borman decided that they should be saved until after splashdown!

The astronauts thought the food was delicious, more like a TV dinner, and much more appetising than the food they had been eating on the mission. In fact, the crew had found their meals so unappealing that they had been under-eating throughout the mission, so their turkey dinner was a real morale booster.

The new “wetpack” container is breakthrough in space food development: a thermostabilized package that retains the normal water content of the food, which can be eaten with a spoon. I’ll have to write more soon about space food, as the new meals and menus that are being developed for Apollo lunar missions are a real breakthrough in astronaut nutrition.

The Final Leg

The return cruise to Earth was the quietest part of the mission for the crew, giving them time to rest after an eventful historic mission. Around 124 hours into the flight, the astronauts broadcast their sixth and final telecast, showing the approaching Earth during a four-minute broadcast.

The crew also had time to take more spectacular photographs of the Earth, such as this image of Australia as they homed in towards their eventual splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

Re-entry is the most dangerous phase of any spaceflight, and Apollo 8 marked the first time that a manned spacecraft had returned from the Moon, re-entering the atmosphere at 24,695 miles per hour! The spacecraft had to enter the Earth’s atmosphere at an angle of 6.5 degrees, with a safe corridor only 26 miles wide – there was very little margin for error!

After jettisoning the Service module and turning the CM around so its heat shield was facing in the direction of flight, Apollo 8 entered the atmosphere, deceleration hitting the astronauts with forces up to 7 Gs, and temperatures outside the spacecraft reaching 5,000 degrees.

Apollo 8's re-entry, captured by one of NASA's Apollo Range Instrumented Aircraft that operate as airborne tracking stations

Apollo 8's re-entry, captured by one of NASA's Apollo Range Instrumented Aircraft that operate as airborne tracking stations

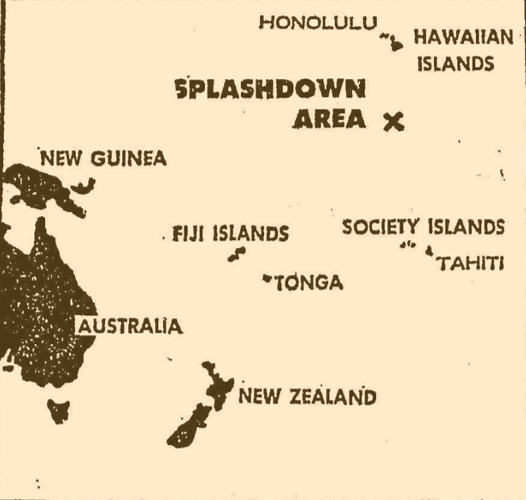

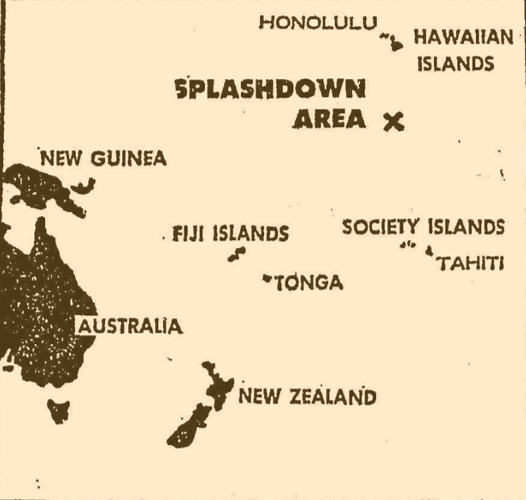

Ionized gases around the spacecraft caused a three-minute communications blackout period. But Apollo 8 came through and safely deployed its three main parachutes, splashing down in the dead of night local time, in the North Pacific Ocean, southwest of Hawaii, home safe after a momentous mission which even the crew had rated themselves as only having a 50% chance of a successful return!

Map of Apollo 8's splashdown area

Map of Apollo 8's splashdown area

Recovered by the USS Yorktown, Borman, Lovell, and Anders were in excellent health after a flight of 147 hours. They returned to Houston for several weeks of debriefing, but he success of their flight means it is now clear that the likelihood of meeting President Kennedy’s goal of a Moon landing before the end of the decade is much higher: Lt.-General Phillips, head of the Apollo programme, has already said there is a slim chance Americans could land on the Moon with Apollo 10 in May or June – one flight earlier than presently planned

After their recovery, the Apollo 8 astronauts addressed the USS Yorktown's crew, very glad to be home!

“You Saved 1968”

After their recovery, the Apollo 8 astronauts addressed the USS Yorktown's crew, very glad to be home!

“You Saved 1968”

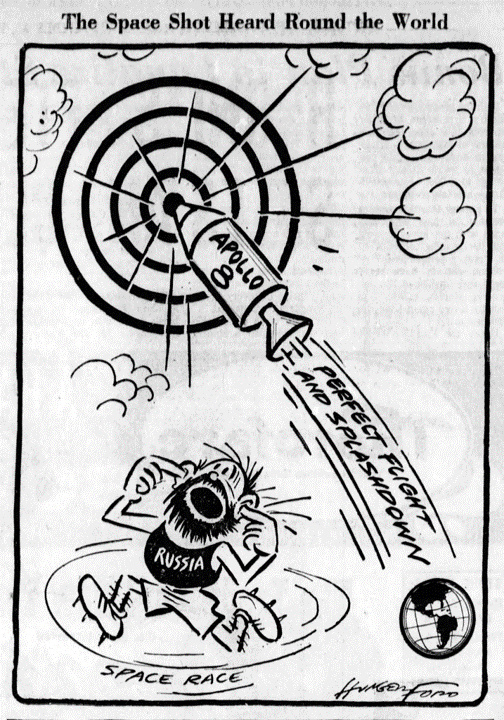

As I noted at the beginning of the first part of this article, 1968 was a year that saw much upheaval around the world. Yet Apollo 8 allowed the year to end on a hopeful note, with its technical triumph of the first manned mission to the Moon, its awe-inspiring views of the Earth from space, and the deeply moving “Genesis broadcast”. Its impact has been beautifully summed up in a telegram from an anonymous well-wisher to Col. Borman which simply said, “Thank you Apollo 8. You saved 1968.”

<

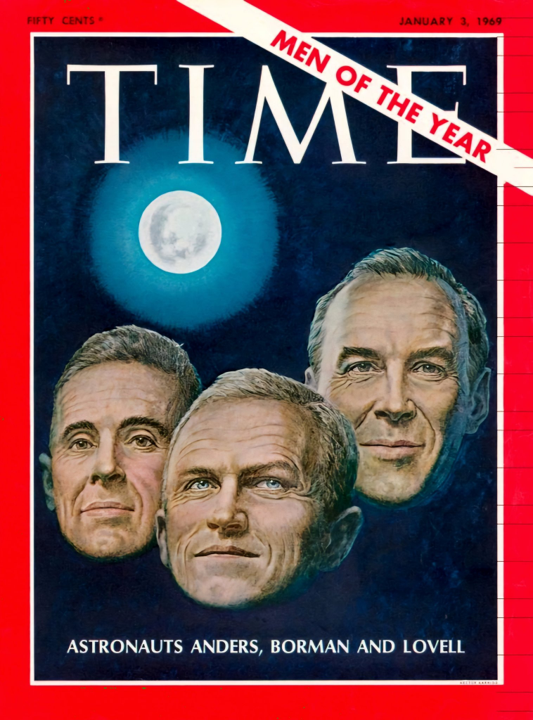

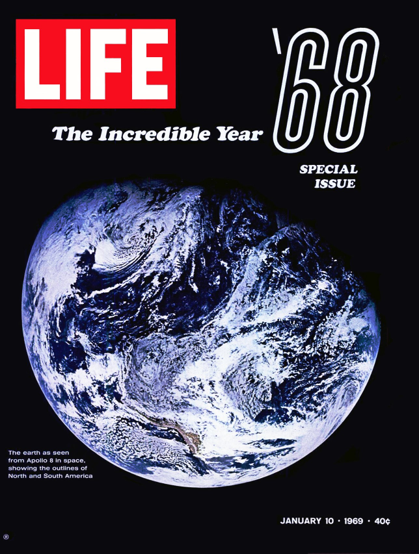

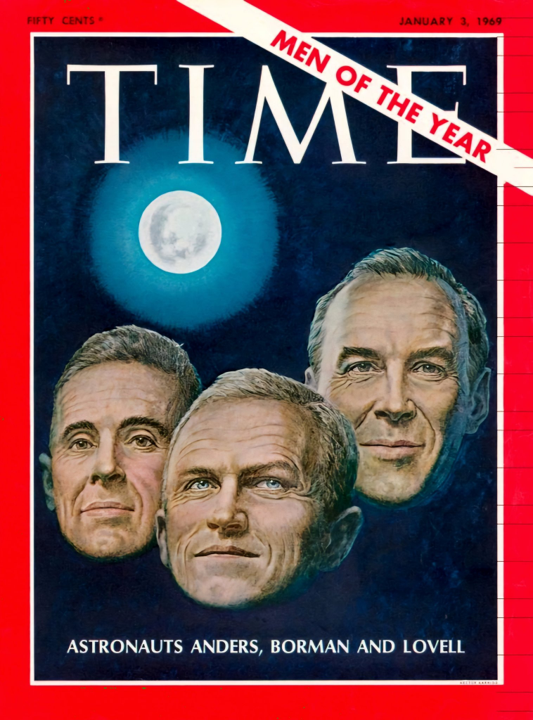

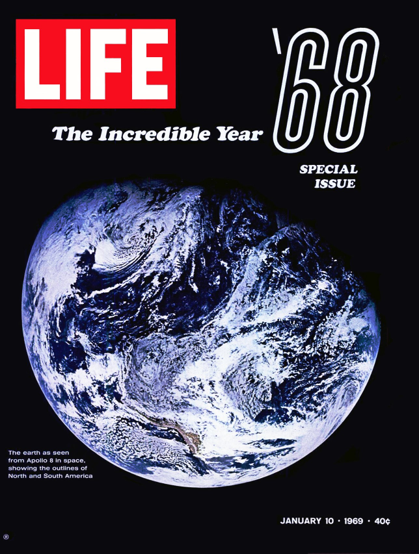

For the influence and impact of their mission, Time magazine has chosen the crew of Apollo 8 as its Men of the Year for 1968, while Life has selected the post-TLI image of the Earth for the cover its 1968 retrospective issue.

The Apollo 8 astronauts have been honoured for their successful mission with ticker tape parades in New York, Chicago and Washington, D.C; they have spoken before a joint session of Congress, and been awarded the NASA Distinguished Service Medal by President Johnson. Has Apollo 8 won the Space Race for the United States? I think it's too early to say, especially in light of the recent

Soyuz 4 and 5 missions. But NASA is certainly giving the Soviet Union a run for its money!

![[April 22, 1970] “Houston, We’ve had a Problem Here!” (Apollo-13 emergency in space)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Apollo-13-13-672x372.jpg)

![[January 22, 1969] NASA’s Christmas Gift to the World Part 2 (Apollo 8 continued)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Apollo-8-Earthrise-672x372.jpg)

"Oh my God!" is what Astronaut William Anders said just before he took this awe-inspiring photograph of the Earth rising over the Moon, as seen from lunar orbit. That was my exact response – and yours, too, I expect – on first seeing this incredible sight. I confidently predict that this amazing view will become one of the defining images of the Space Age

"Oh my God!" is what Astronaut William Anders said just before he took this awe-inspiring photograph of the Earth rising over the Moon, as seen from lunar orbit. That was my exact response – and yours, too, I expect – on first seeing this incredible sight. I confidently predict that this amazing view will become one of the defining images of the Space Age Fuel venting isn't visible in this image of the jettisoned S-IVB stage, but small debris from the separation can be seen floating around it. Although Apollo 8 carried no Lunar Module, this shot shows the LM test article contained in the S-IVB stage

Fuel venting isn't visible in this image of the jettisoned S-IVB stage, but small debris from the separation can be seen floating around it. Although Apollo 8 carried no Lunar Module, this shot shows the LM test article contained in the S-IVB stage Taken just around the time of TLI, this view from high orbit shows the Florida peninsula, with Cape Kennedy just discernible, and several Caribbean islands

Taken just around the time of TLI, this view from high orbit shows the Florida peninsula, with Cape Kennedy just discernible, and several Caribbean islands The view of Earth after S-IVB stage separation. From the Americas to west Africa, and from daylight to night, for the first time humans could see their entire planet at a glance!

The view of Earth after S-IVB stage separation. From the Americas to west Africa, and from daylight to night, for the first time humans could see their entire planet at a glance! The first mission status report for Apollo 8, sent to the NASA tracking stations around the world, for release to local media. Dated some 19 hours after launch, it outlines some of the activities of the early part of the coast to the Moon

The first mission status report for Apollo 8, sent to the NASA tracking stations around the world, for release to local media. Dated some 19 hours after launch, it outlines some of the activities of the early part of the coast to the Moon

Astronaut Anders shows us his toothbrush (top) and Jim Lovell wishes his mother "Happy Birthday" (bottom) during Apollo 8's first deep space broadcast

Astronaut Anders shows us his toothbrush (top) and Jim Lovell wishes his mother "Happy Birthday" (bottom) during Apollo 8's first deep space broadcast The Apollo 8 second broadcast view of the Earth as we saw it on television (above) and how Capcom Collins saw it on his monitors in Mission Control (bottom). Would alien visitors to our solar system think anyone lived there?

The Apollo 8 second broadcast view of the Earth as we saw it on television (above) and how Capcom Collins saw it on his monitors in Mission Control (bottom). Would alien visitors to our solar system think anyone lived there?

A view of the Moon, finally visible as Apollo 8 approached and prepared to go into orbit

A view of the Moon, finally visible as Apollo 8 approached and prepared to go into orbit The Manned Space Flight Network station at Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra, was tracking Apollo 8 as it went behind the Moon and received the first signals as it re-emerged, safely in lunar orbit

The Manned Space Flight Network station at Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra, was tracking Apollo 8 as it went behind the Moon and received the first signals as it re-emerged, safely in lunar orbit

Jim Lovell's "sand pile" on the Moon!

Jim Lovell's "sand pile" on the Moon! View of the Moon's surface during the third Apollo 8 television broadcast

View of the Moon's surface during the third Apollo 8 television broadcast Awestruck, they scrambled so quicky to capture the vision that no-one is quite sure now who took which picture, although it seems that Col. Borman may have snapped the first black and white photograph, and Bill Anders a number of breathtaking colour images of the Earthrise.

Awestruck, they scrambled so quicky to capture the vision that no-one is quite sure now who took which picture, although it seems that Col. Borman may have snapped the first black and white photograph, and Bill Anders a number of breathtaking colour images of the Earthrise. Apollo 8's Earthrise images are usually published oriented with the lunar horizon at the bottom, as that is how we are used to seeing the Moon rising over the horizon on Earth. But the orientation of astronauts' orbit meant that they actually saw the Earth appearing to rise 'sideways', as seen in this original version of Major Anders' photograph

Apollo 8's Earthrise images are usually published oriented with the lunar horizon at the bottom, as that is how we are used to seeing the Moon rising over the horizon on Earth. But the orientation of astronauts' orbit meant that they actually saw the Earth appearing to rise 'sideways', as seen in this original version of Major Anders' photograph This spread from the 15 January issue of the Australian Women's Weekly is just one example of thousands of magazine and newspaper articles already featuring the Earthrise photograph and Apollo 8's other amazing pictures

This spread from the 15 January issue of the Australian Women's Weekly is just one example of thousands of magazine and newspaper articles already featuring the Earthrise photograph and Apollo 8's other amazing pictures A view of the Moon seen by the audience on Earth while the crew of Apollo 8 read from the Book of Genesis

A view of the Moon seen by the audience on Earth while the crew of Apollo 8 read from the Book of Genesis Families around the world gathered on Christmas Eve/Christmas Day (depending on where you were!) to watch Apollo 8's broadcast

Families around the world gathered on Christmas Eve/Christmas Day (depending on where you were!) to watch Apollo 8's broadcast A view inside the Command Module, during the fifth Apollo 8 television broadcast

A view inside the Command Module, during the fifth Apollo 8 television broadcast An image from the fifth broadcast taken directly from a monitor at the Honeysuckle Creek tracking station. It shows Bill Anders demostrating how to prepare a meal

An image from the fifth broadcast taken directly from a monitor at the Honeysuckle Creek tracking station. It shows Bill Anders demostrating how to prepare a meal Slayton also included three miniature bottles of brandy with the meal, although Borman decided that they should be saved until after splashdown!

Slayton also included three miniature bottles of brandy with the meal, although Borman decided that they should be saved until after splashdown!

Apollo 8's re-entry, captured by one of NASA's Apollo Range Instrumented Aircraft that operate as airborne tracking stations

Apollo 8's re-entry, captured by one of NASA's Apollo Range Instrumented Aircraft that operate as airborne tracking stations Map of Apollo 8's splashdown area

Map of Apollo 8's splashdown area  After their recovery, the Apollo 8 astronauts addressed the USS Yorktown's crew, very glad to be home!

After their recovery, the Apollo 8 astronauts addressed the USS Yorktown's crew, very glad to be home! <

< For the influence and impact of their mission, Time magazine has chosen the crew of Apollo 8 as its Men of the Year for 1968, while Life has selected the post-TLI image of the Earth for the cover its 1968 retrospective issue.

For the influence and impact of their mission, Time magazine has chosen the crew of Apollo 8 as its Men of the Year for 1968, while Life has selected the post-TLI image of the Earth for the cover its 1968 retrospective issue.

![[December 28, 1968] A Christmas Gift to the World – Part 1 (Apollo 8)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Apollo-8-patch-672x372.png)

![[November 16, 1966] A Grand Finale (Gemini 12)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/G-12-mission-patch-672x372.png)

![[December 20, 1965] Rendezvous in space (Gemini 6 and 7)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/651215b3-672x372.jpg)