by Gideon Marcus

On the small screen

A few weeks ago, President Johnson signed into effect the Public Broadcasting Act. Its purpose, among other things, is to turn a decentralized constellation of educational stations and program producers into a government-funded network. It's basically socialism vs. the vast wasteland.

Given the quality of programming I've seen produced by National Education Television, particularly on independent station KQED-San Francisco (e.g. "Jazz Casual" and "The Rejected"), I am all for this move. Indeed, I've recently come across a show that has really sold me on public television.

NET Journal is a series on political matters of the day. In December, they had a program that showed the results of a week-long workshop in which 12 affluent young men and women of a multitude of ethnicities lived together and discussed their prejudices. What they determined was surprising to them, and maybe to us. As we saw in the film Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, even in the most bleeding heart liberal, there is prejudice; and it's not just directed from whites to minorities.

This week, we caught an interview with four journalists in Saigon. Recently, LBJ and General Westmoreland have been cheerleading the effort in Vietnam, saying that the three-year commitment of half a million troops is bearing fruit. The South Vietnam-based journalists dispute this rosy view. They say progress has been slow, that the South Vietnamese army is hopelessly corrupt and must be reformed from the head down if it is to operate effectively without American support, and that we are not engaged in "nation-building" because there is currently no nation. The elections are meaningless so long as there be no real choices to be made, so long as bribes and payoffs accomplish more than the rule of law.

Withering stuff. Next week, the program will be on draft-dodgers.

On the small page

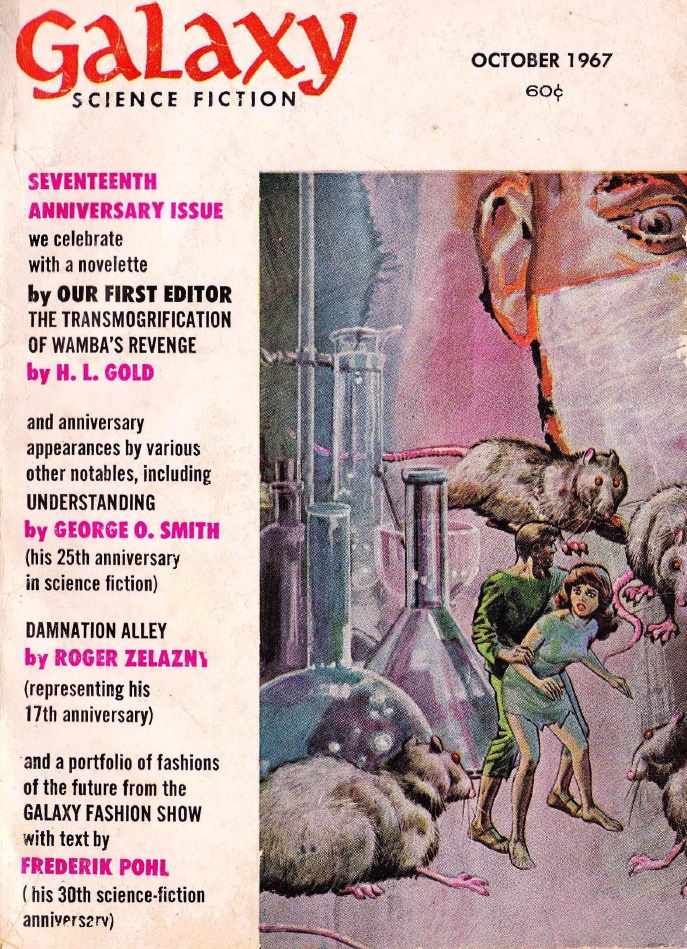

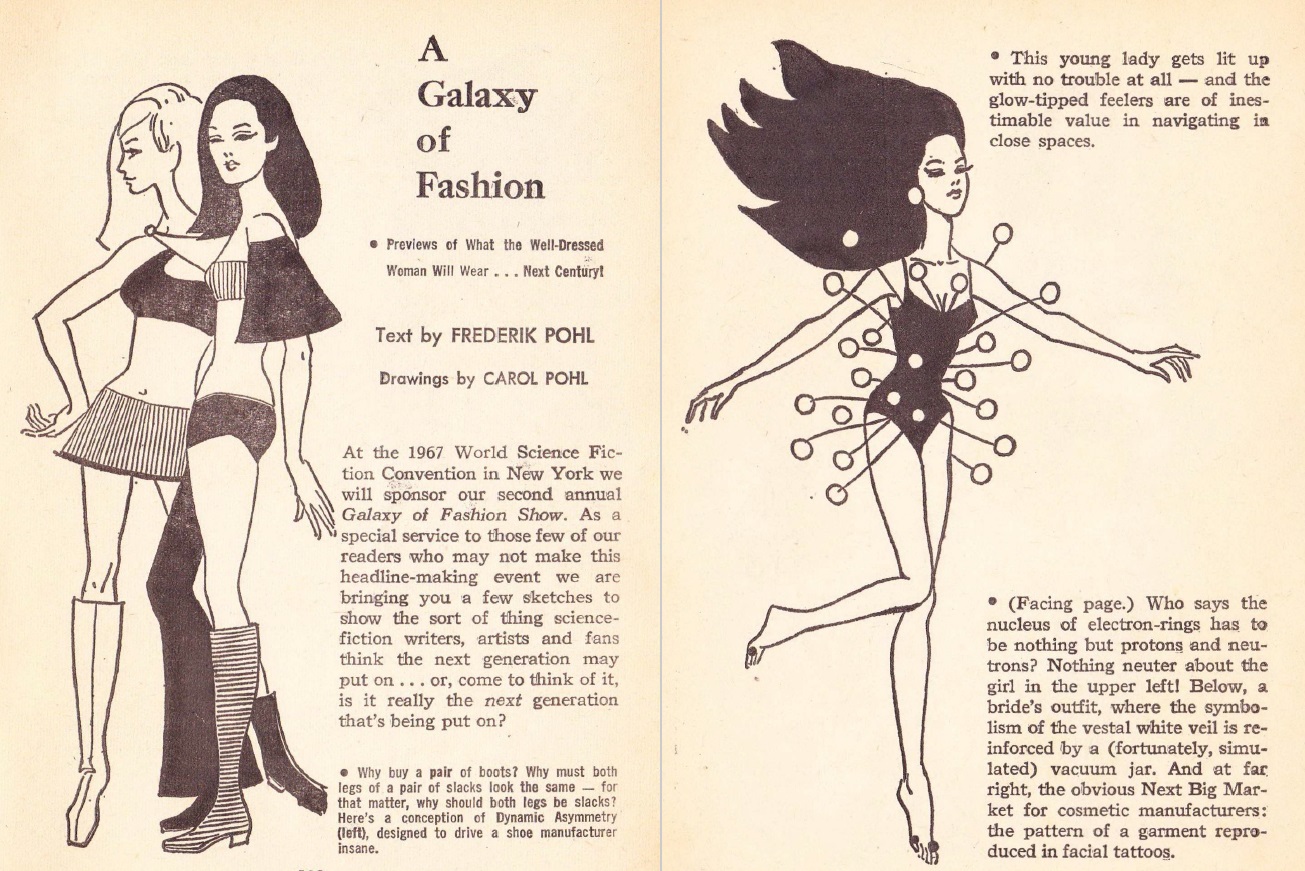

Galaxy Science Fiction is also an exellent, long-running source of information and entertainment. This month's issue is a particularly good example.

by Jack Gaughan

A Tragedy of Errors, by Poul Anderson

Anderson has established a reputation for producing some of the "hardest" SF around, laden with astrophysical tidbits. On the other hand, his quality varies from sublime to threadbare. Luckily, his latest novella lies far closer to the former end of the scale.

Tragedy takes place in what appears to be the far future of his Polysotechnic League history. The loose interstellar confederation of planets became an empire and subsequently went into decline a la the worlds in H. Beam Piper's Space Viking universe and Asimov's Foundation setting. I really like these "after the fall" stories of folks trying to patch a polity back together, maybe better than it was before.

by Gray Morrow

This particular story is the tale of Roan Tom, Dagny, and Yasmin, the crew of the merchant-pirate Firedrake. Their ship is in desperate need of repairs, and the only planet within range of the married trio is a Mars-sized world around a swollen orange sun. Luckily, said world was once a human colony of the Empire and thus may have the resources needed to fix a starship.

Unluckily, the planet has been recently plundered by pirates, and the inhabitants do not take kindly to strangers–especially ones that call themselves "friends."

There's a lot to like about this riproaring tale of aerial maneuvers, overland evasion, and fast-talking diplomacy. For one, two of the main characters are women, and highly competent ones at that. Moreover, it is an ensemble cast, with each of the three coming into the spotlight for extended periods of time.

There is also a mystery of sorts, here…or several, really, all woven together: how does this undersized planet have an atmosphere? Indications are that this is a young world, but why, then, does the dense planet have so little surface metal? And why is the star so unstable, prone to devastating solar storms that play hell with the planet's weather? Solving this astronomical puzzle proves key to addressing the Firedrake crew's more immediate problems.

Of course, you have to like detailed explanations of stellar and planetary parameters and phenomena. I personally love this sort of thing, but others may find their eyes glazing. On the other hand, there's plenty to enjoy even if you decide to let the science wash over you. The sanguine antics of Roan Tom, the determined toughness of Dagny, the more refined and tentative brilliance of Yasmin. These are great characters, and I'd like to see more of them.

Four stars.

The Planet Slummers, by Terry Carr and Alexei Panshin

A pair of young thrift store bargain hunters are, in turn, scooped up by a pair of alien specimen collectors. I think the story is supposed to be ironic, or symbolic, or something.

Forgettable. Two stars.

Crazy Annaoj, by Fritz Leiber

by Jack Gaughan

Ah, but then we have the story of a different couple: a superannuated trillionaire and a dewy (but flinty) eyed young starlet. There's is a love fated for the ages, but not the way you might think.

Just a terrific tale told the way only Leiber (or maybe Cordwainer Smith) could tell it.

Five stars.

Street of Dreams, Feet of Clay, by Robert Sheckley

by Vaughn Bodé

Imagine moving to the city of the future: clean, architecturally pleasing, smog-free, crammed with creature comforts. Now imagine the city is run by a computer brain…with the personality of a Jewish mother.

Bob Sheckley is Jewish, so I suspect he didn't have to strain his imagination much for this one. Droll, but a little too painful and one-note to be great.

Three stars.

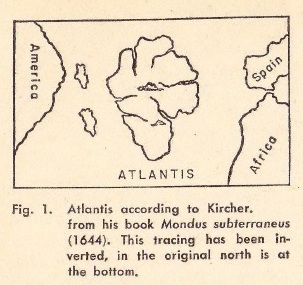

For Your Information: Epitaph for a Lonely Olm, by Willy Ley

This is a pretty dandy story about a sightless cave salamander that lives its whole life in the water, thus eschewing the amphibian portion of its nature. Thanks to this creature, we have the concept of "neoteny"–the retention of juvenile traits for evolutionary advantage. The blind, pale beast also ensured the fame of Marie von Chauvin, a 19th Century zoologist.

Four stars.

Sales of a Deathman, by Robert Bloch

by Jack Gaughan

How do we combat the exploding birth rate? By making suicide sexy, thus exploding the death rate!

Bloch's modest proposal would be better suited to a three line comedy routine than a several-page vignette. Three stars.

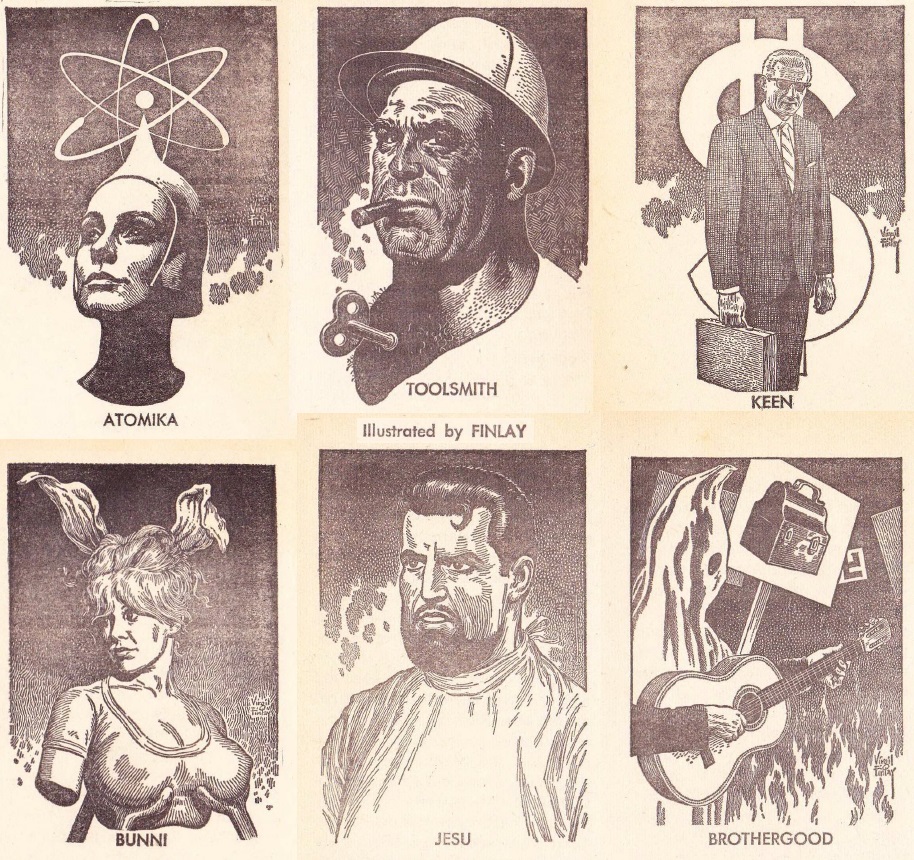

Total Environment, by Brian W. Aldiss

by Jack Gaughan

Crammed into a ten-story self-contained habitat, 75,000 persons of Indian descent live a life of increasing desperation and squalor. At first, we are given to believe that the settlement is a natural response to the crushing pressure of overpopulation. As it turns out, the Ultra-High Density Research Establishment (UHDRE) is actually a deliberate experiment in inducing psychic abilities through exposure to unique pressures. Just 25 years ago, the site had a population of only 1500. Now, teeming to bursting, the hoped-for psionic adepts are appearing–and an empire in a teapot is arising on UHDRE's Top Deck to take advantage of them.

Aldiss writes a compelling story. One thinks it's just the second coming of Harrison's Make Room! Make Room! until it isn't. In some ways, this actually hurts the story, causing it to lose focus. On the other hand, the setting is so well-drawn, and the situation suspenseful enough, that it still engages and entertains.

Four stars.

How They Gave It Back, by R. A. Lafferty

by Gray Morrow

The last mayor of Manhattan finds The Big Apple isn't worth the bother, now that it's degenerated into a ruined, gangland state run by a quintet of bandits. Thankfully, the original owners will buy it back–for its original fee.

Again, this might have made a humorous short bit. As is, you see the punchline from the first words (the title and illo help), and the slog isn't worth the ending.

Two stars.

The Big Show, by Keith Laumer

by Wallace Wood

Last up, a frothy adventure featuring a TV star recruited to infilitrate the last cannibal island in the South Pacific to thwart a nefarious Soviet scheme. This is yet another in the recent spate of stories involving total sensory television in which hundreds of millions viscerally experience the lives of actors.

Unlike Kate Wilhelm's or George Collyn's spin on the subject, Laumer doesn't do very much with the gimmick. Instead, it's another of his midly amusing but eminently forgettable yarns.

Two stars.

Summing up

Despite a sprinkling of clunkers, the latest Galaxy delivers the goods. Two good novellas, a fine nonfiction piece, and an excellent Lieber short would have filled F&SF nicely. So just pretend that the other stories don't exist and enjoy the good stuff.

And then tune in to NET Journal the next few weeks while you wait for the next issue!

![[January 16, 1968] Worthy programming (February 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[December 6, 1967] Brotherly Love (<i>Dangerous Visions</i>, Part Two)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/DangerousVisions1stEdxx971656156_465_692_int-2.jpg)

![[November 8, 1967] Four to go (December 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/671108cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 14, 1967] Stuck in the Past (October 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/670910cover-672x372.jpg)

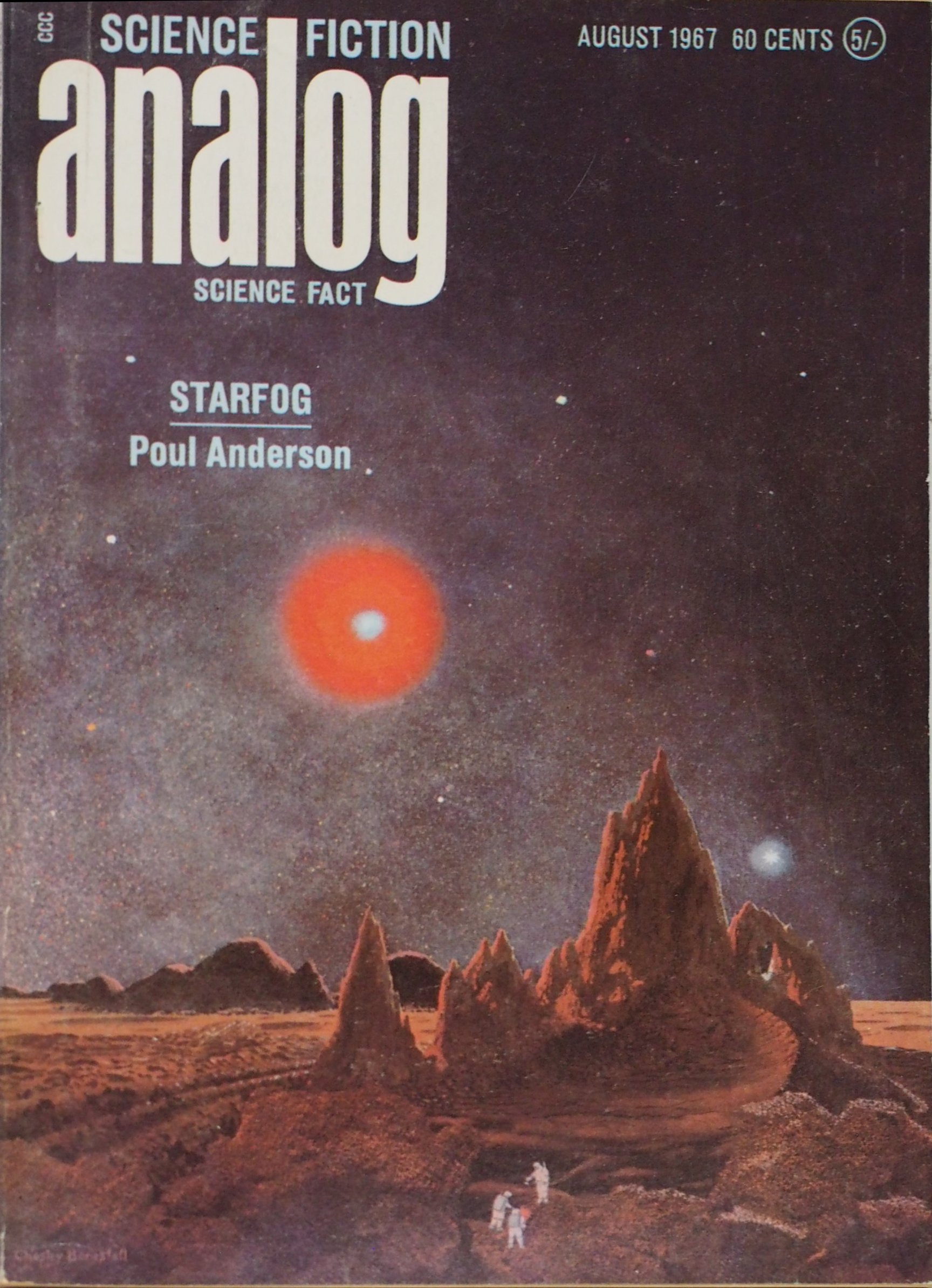

![[July 31, 1967] Canceling waves (August 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670731cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 8, 1967] Family lines (August 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670710cover-672x372.jpg)

![[May 12, 1967] There and Back Again (June 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/670512cover-672x372.jpg)

![[February 28, 1967] The Big Stall (March 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670228cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 31, 1967] The Law of Averages (February 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670131cover-672x372.jpg)

![[December 31, 1966] Barriers to quality (January 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661231cover-672x372.jpg)