by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

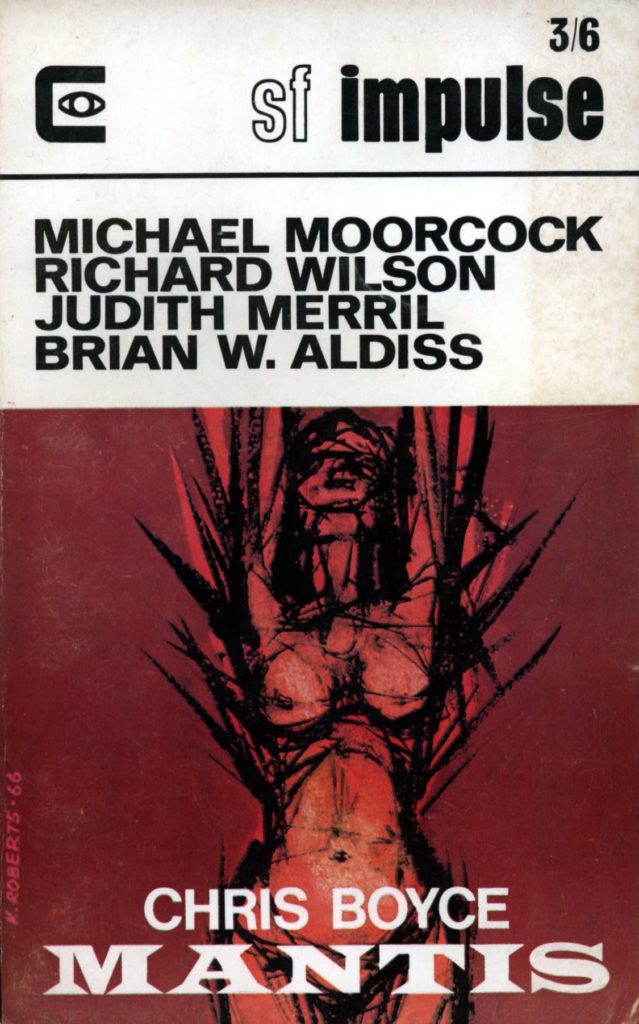

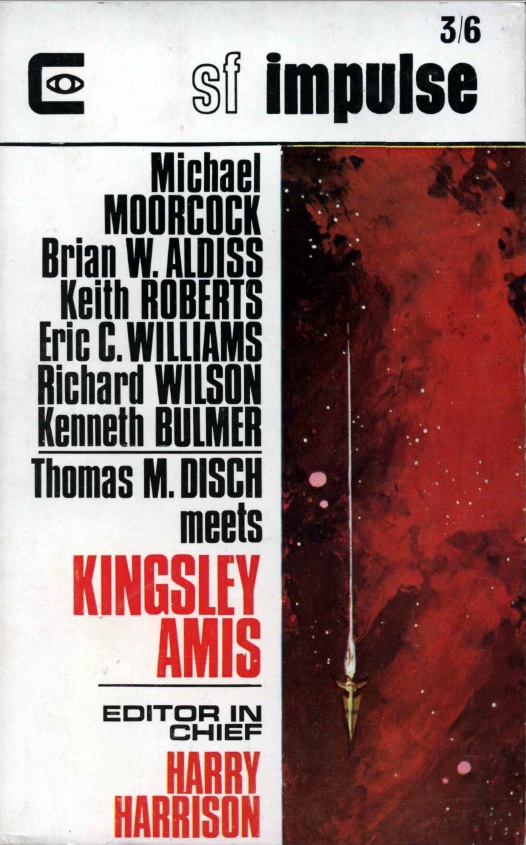

So generally, post-Christmas and in the cold of winter, 1967 is settling into a routine, I guess. Except in the British magazines, where things are rather more turbulent. My suspicions were raised when the postman only delivered a copy of SF Impulse this month.

Now it is possible that New Worlds has been delayed in delivery–y’know, Winter!–but after the recent rumours and rumblings that things were not well at the magazines, I did a little rummaging and asked around to see if I could find out what was going on.

Whisper it quietly, but it seems that things are really bad financially–even for New Worlds, which has the higher circulation of the two–to the point that the publishers are seriously considering closing not one, but both magazines.

More as I get it, but frankly, it’s not looking good.

Cover illustration by Agosta Morol

To the SF Impulse issue. There are also signs here that things are not good.

The Managing Editor (interesting phrase!) Keith Roberts points out at the start that the Editor-in-Chief Harry Harrison is “absent, having made tracks for Philadelphia”. Is this rather ambiguous statement just a case of Harry being busy? As a writer, critic and editor Harrison does have a lot of fingers in pies, to be honest, which is presumably why Roberts does most of the leg-work here at SF Impulse.

But all I can think of is that the last time this happened, with editor Kyril Bonfiglioli taking time off to go stargazing(!), the magazine changed from Science Fantasy to Impulse not long after. The phrase “Rats deserting a sinking ship” also springs to mind, though that would be most uncharitable–Harrison is most certainly not a rat! But it is worrying that things may be changing behind the scenes.

But at least this Editorial space gives Roberts the opportunity to step up, as he has been doing for a while, admittedly, and give his opinions in the Editorial on the material in the issue, which he does. All good, even if (like much of the magazine this month) it feels a little like space-filler.

Might be something to read after you’ve read the stories, though.

Illustration by Keith Roberts

The Bad Bush of Uzoro by Chris Hebron

After last month’s story Coincidences, from Chris, we begin with a story I liked more. This one has a Weird Tales vibe, in the form of a story of a haunted mission in Africa as told by a Catholic priest–it even mentions Lovecraft. Not bad, though, and endearingly different with its mentions of African culture, even if there is an element of imperialistic “fear the foreigner” to this one. 4 out of 5.

Just Passing Through by Brian W. Aldiss

Illustration by Keith Roberts

Harry Harrison may not be about much this month, but his friend Brian Aldiss is (Again: when do we ever see the two together?)

This is unusual for Brian: a style that is almost Ballardian, filled with ennui and decay. Colin Charteris is in France on his way to England. His general musings on his stop-over through a mouldering French town also reveals to us that this is a future after the superpowers have released psychedelic drugs in what is being called the Acid Head War. The result is that many of the population are insane, locked away in their own heads as much as they are in institutions. The remainder, such as those seen here in France, seem to live a transitory existence. Whilst this intriguing situation is slowly revealed, the point of the story is less clear, and just as the reader is reeled in, the story ends. More of a mood piece than an actual story, I think.

Brian deserves credit for deliberately pushing the experimental side of science fiction in this story. It is a lot more serious than much of his work, but it feels very much like it is the beginning of a longer story. Nevertheless, it is unusual enough and odd enough for me to give it 4 out of 5.

Inconsistency by Brian M. Stableford

Don’t be fooled by the “new writer” comment given at the top of this story. We have met Brian before, both as Brian Stableford in the October 1966 issue and as co-writer Brian Craig back in the November 1965 issue–not to mention his letters to Kyril back in the same issue. Here he’s writing a fantasy story with a deliberately allegorical touch. Characters live around a village slowly disappearing in the sea. They have no idea of why they are there or how they got there. At the end the sea covers all. BUT WHAT DOES IT REALLY MEAN? Another symbolic puzzle which will either be appreciated or cause befuddlement. 3 out of 5.

The Number You Have Just Reached by Thomas M. Disch

Illustration by Keith Roberts

More from Mr. Disch this month, on the creepier side. It is about Justin Holt, the last man in the world who, staring out from his fourteen-storey apartment, receives a telephone call from someone who may be the last woman in the world. But is she real or is she a figment of his imagination? A story of fear and claustrophobia that doesn’t end well. This one’s fine, but I didn’t like it as much as some of his more recent stories. 3 out of 5.

The Pursuit of Happiness by Paul Jents

Another story from the often-underwhelming Mr. Jents, who last appeared in the June 1966 issue. Krane lives on Aligua, a distant planet which has spurned technology due to once being enslaved by computers, but have integrated circuits implanted in their heads to cope with their lives. Another story that deals with what is real and what is imaginary. One of Paul’s better stories, but really nothing special. 3 out of 5.

It’s Smart to Have an English Address by D.G. Compton

D.G. is a writer who tends to make me think of Fred Hoyle, strangely. Not sure why, other than he has this very British tone. And so it is here. Paul Cassevetes goes to meet his old friend Joseph Brown, a concert pianist (see also Hoyle’s October the First is Too Late where the main character is a composer). Doctor McKay and Paul try to get Joseph to record brain patterns whilst playing one of his finest pieces to give listeners a better experience. Joseph is resistant, feeling that such techniques do not get to the essence of a performance. At the end Joseph suffers a stroke, which makes the process rather redundant. A story of friendship and rather elegiac, if a little bit convenient at the end. I liked it but could see some thinking the story is mawkish. 3 out of 5.

Impasse by Chris Priest

Chris is one of our new young writers beginning to make an appearance in the magazines: last time it was with his Ballardian pastiche Conjugation in the December 1966 issue of New Worlds. This one seems to be an attempt to write short satirical Space Opera and shows the futility of conflict. Insults and threats are made between a Denebian and the Earth Field-Marshal which escalate until one of them shoots the other. Not sure I really get the point. 2 out of 5.

See Me Not by Richard Wilson

Another returning writer. He is popular, I understand, though his stories rarely register with myself for some reason. So the fact that Keith Roberts mentions in his Editorial that this is a “long, complete story” made my heart sink. But I was surprised, even if we are reusing old ideas here. This time it is about invisibility–thank you, Mr H. G. Wells! (Actually, I’ve only just realised that this may have been written as a result of that recent centennial celebration of Mr Wells’s birth.)

Avery wakes up to find himself invisible. Much of the rest of the story is about how he deals with this situation with his wife, Liz, his children, Bobby and Margie, and his doctor, Mike Custer. Lots of social issues ensue. The scientists try to work out what has happened and why. At the end of the story, Avery and Liz, who also becomes invisible, walk off together to live happily ever after it seems.

This is an attempt to write a lighter version of Wells’s tale, but ends up something more akin to an episode of your TV series Bewitched than the original Wells story. Although nowhere near as good as Wells’s version, for me this is a better story from Richard. 3 out of 5.

Keith Roberts rereads ‘The True History’ of Lucian of Samosatos

Illustration by Keith Roberts

And talking of Keith Roberts… This is space-filler of the highest order, as the writer gives us his interpretation of an ancient Greek classic. Not quite sure of its purpose, although Roberts writes well enough and brings to light an old classic that may be worth a second glance. Made me yearn to read a Thomas Burnett Swann story, which may not really be the point of this piece. 2 out of 5.

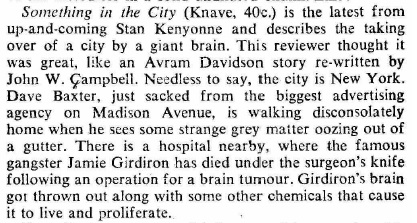

Book Fare (Reviews)

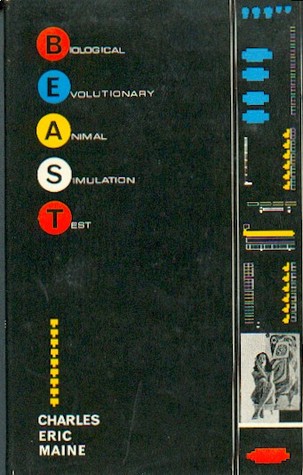

Book reviews from Alistair Bevan, also known as Keith Roberts. There are reviews of Planets for Man by Stephen H. Dole and Isaac Asimov, Other Worlds Than Ours by C. Maxwell Cade, Colossus by D. F. Jones, Window on the Future edited by Douglas Hill, Ten From Tomorrow by E. C. Tubb and The Machineries of Joy by Ray Bradbury.

Letters to the Editor

Last month I said that the ongoing discussion about Sex in SF that E. C. Tubb started a couple of issues ago felt like it was an attempt to generate mock outrage. With hindsight I now realise that the magazine probably has enough drama going on. Anyway, this month the Letters pages have a spirited defense of “WSB”, better known as William S. Burroughs to you and me, and a discussion of the meaning of Science Fiction, a competition that Harry opened when he first took over from Kyril. There is a winner, step up Peter Redgrove!

Summing up SF Impulse

Keith Roberts is clearly working above and beyond the usual here and should be credited with pulling together an issue even if some material was not up to the usual standard. Let’s hope that the magazine continues, although the signs are doubtful.

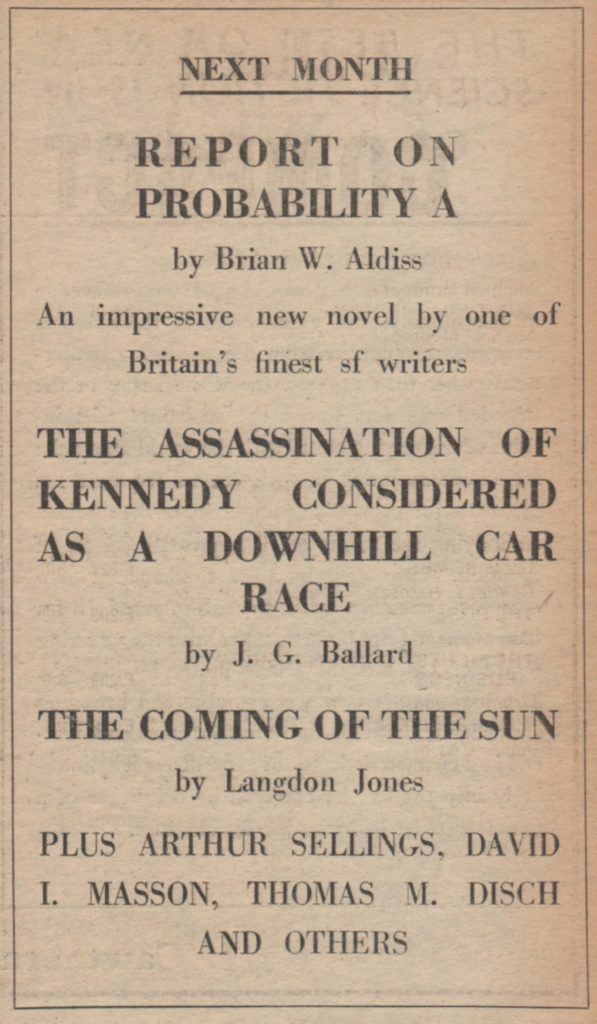

An advertisement on the last page of the issue. Is this an omen or a cryptic clue? Is there life after death for New Worlds or SF Impulse?

Until the next (hopefully!)

![[January 24, 1967] Absenteeism and Making Do <i>SF Impulse</i>, February 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/SF-Impulse-Jan-67-672x372.jpg)

![[January 14, 1967] First batch (January Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670114covers-672x372.jpg)

![[December 28, 1966] Ice Worlds, Telepathic Martian Mice and Echoes (<i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, January 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/New-Worlds-Impulse-Jan-67-1-672x372.jpg)

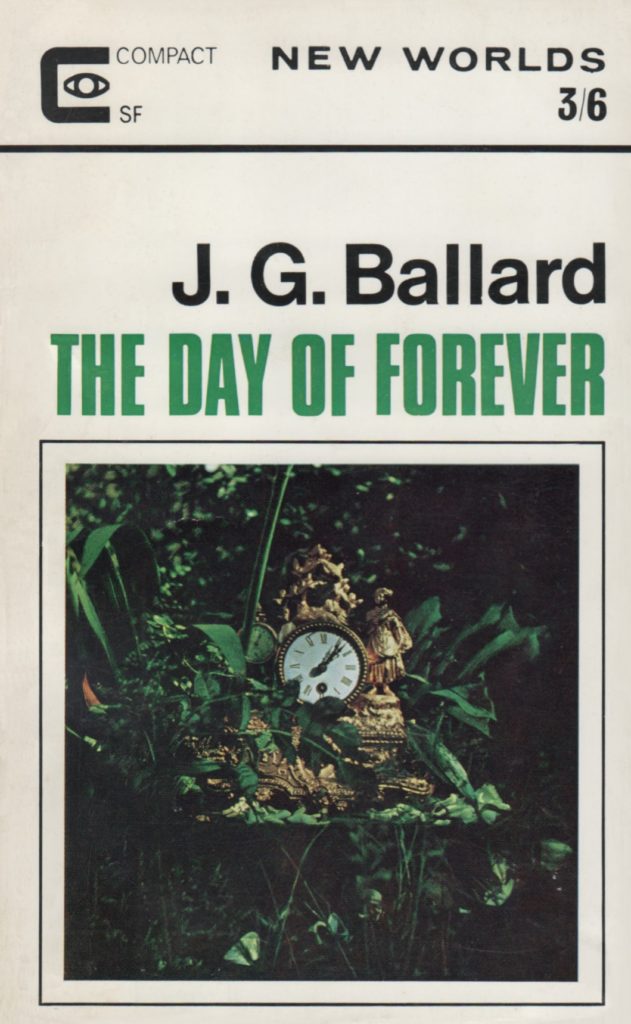

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

![[December 22, 1966] Who's In Charge Here? (<i>The Monitors</i> by Keith Laumer and <I>The Nevermore Affair</i> by Kate Wilhelm)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661222covers-672x372.jpg)

![[December 16, 1966] The God Slayers (two computer-themed novels)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661216covers-672x372.jpg)

![[December 10, 1966] Hot and Cold (December Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661210covers-672x372.jpg)

![[November 26, 1966] White Boats, Whales and Disch, <i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, December 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Dec-1966-672x372.jpg)

Illustration by Unknown Artist

Illustration by Unknown Artist

Illustration by Keith Roberts- the author!

Illustration by Keith Roberts- the author!

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn

![[October 24, 1966] Birds, Roaches and Rings, <i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, November 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-November-66-672x372.jpg)

![[September 28, 1966] Garbage and Aliens (October 1966 <i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Sept-1966-672x372.jpg)

![[August 28, 1966] Messiahs and Resignation (<i>New Worlds</i> and <i>SF Impulse</i>, September 1966)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/New-Worlds-SF-Impulse-Sept-1966-672x372.jpg)