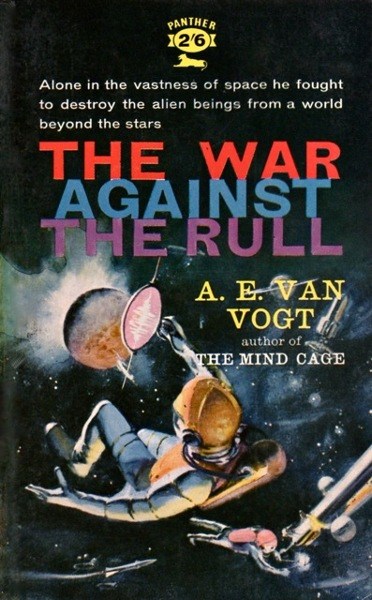

Less than a generation ago, Adolf Hitler made eugenics–the selective breeding of humans for desired traits–a dirty word. But what if a race of bona-fide supermen were created through the direct manipulation of DNA and presented as a fait accompli? What would be the moral ramifications, and how would the "normals" react? James Blish's attempts to tackle these questions in his new book, Titans' Daughter.

From the cover, you might gather that Daughter is the story of Sena, one of the eight-foot tall, super-intelligent test tube creations of the brilliant Dr. Frederick R. Hyatt. It is, but only tangentially. Rather, it is really the account of Maurice St. George, the "best-adjusted" of the mutants, known as "tetras" for their tetraploidal genetic make-up (having four pairs of chromosomes instead of two like "normal" diploid people).

Resentful of the unrestrained acrimony and discrimination the tetras endure at the hands of the diploids, he secretly plots a rebellion. By furtively training a tetra army in the guise of training them in a new, giants-only football league, and through the creation of reactionless drives converted into deadly beams, St. George creates a powerful fifth column. A lone spark would ignite a powder keg of interracial war: the murder of Dr. Hyatt. Sena's role is a minor one–as one of the few tetra females, St. George has tapped her to be the mother of a new generation of giants, with or without her consent!

Daughter is an uneven book in a lot of ways. Half of it originally appeared almost a decade ago as the novella, Beanstalk; I can only imagine that the prior story contained all of the basic plot, and that the novel simply provides expansion. Otherwise, it would be incomprehensible.

Regardless of subsequent embellishments, Daughter is fundamentally an old story, and it feels dated. Society in the book's early 21st Century feels just like the early '50s with the addition of the friction created by the tetras. The viewpoint is third-person omniscient, and we shift characters frequently and jarringly. While Blish occasionally offers up a clever turn of phrase, he also litters the text with overlong and awkward scientific exposition. The science itself is dodgy. Basically, the thing reads like a serial from a lesser digest (which, spiritually, it is). This is a shame because the subject matter is fascinating, even if Blish just scratches the surface, and there are moments of genuine quality.

For instance, the references to the previous mini-rebellion, the Pasadena incident that left two dozen tetras immolated alive in their cross-shaped compound. Or the excellent court scene in which a brilliant attorney provides a stirring defense for the tetra falsely accused of Dr. Hyatt's killing. Or the scenes in which we get glimpses of the two-way resentment and mistrust between the two tribes of humanity, ancient and newborn. It is tantalizing to think what might have been if Sturgeon or Henderson had made a more nuanced pass at the issue–or even a completely present-day Blish, using his current, superior skills to try again from scratch.

Instead, Daughter is somewhat engaging but ultimately unfulfilling pulp that pendulums from super-science to action-adventure. I look forward to someone someday taking Daughter's theme and doing it right.

Three stars.