In my last piece, I discussed how magazines can be better experiences than books because the variety mitigates uneven quality. A good book lasts longer than a magazine, but a bad book lasts longer than eternity.

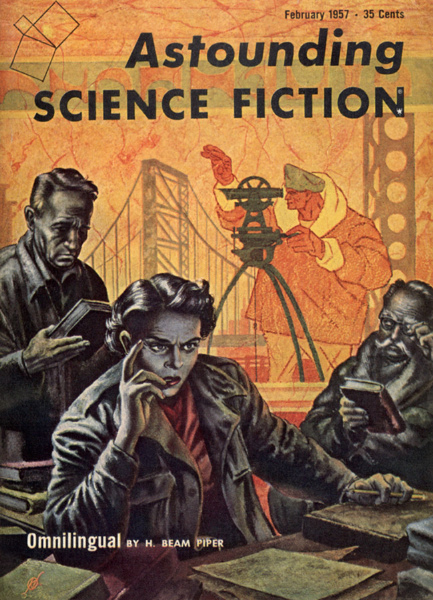

I try to read a new book every month. With the decline of the science fiction digest, the novel seems to be taking its place as the medium of choice for new material. March's book was The Door Through Space, by new(ish) author, Marion Zimmer Bradley.

I try not to let personal factors sway me when assessing the value of fiction, but I'm only human. On the positive side, I was pleased to find a book by a woman author; on the other hand, Bradley is a weird occultist a la L. Ron Hubbard. Let's just call the two factors mutually balancing, and I'll review the book on its merits.

In the book's preamble, the author writes:

I've always wanted to write. But not until I discovered the old pulp science-fantasy magazines, at the age of sixteen, did this general desire become a specific urge to write science-fantasy adventures.

I took a lot of detours on the way. I discovered s-f in its golden age: the age of Kuttner, C. L. Moore, Leigh Brackett, Ed Hamilton and Jack Vance. But while I was still collecting rejection slips for my early efforts, the fashion changed. Adventures on faraway worlds and strange dimensions went out of fashion, and the new look in science-fiction — emphasis on the science — came in.

So my first stories were straight science-fiction, and I'm not trying to put down that kind of story. It has its place. By and large, the kind of science-fiction which makes tomorrow's headlines as near as this morning's coffee, has enlarged popular awareness of the modern, miraculous world of science we live in. It has helped generations of young people feel at ease with a rapidly changing world.

But fashions change, old loves return, and now that Sputniks clutter up the sky with new and unfamiliar moons, the readers of science-fiction are willing to wait for tomorrow to read tomorrow's headlines. Once again, I think, there is a place, a wish, a need and hunger for the wonder and color of the world way out. The world beyond the stars. The world we won't live to see. That is why I wrote THE DOOR THROUGH SPACE.

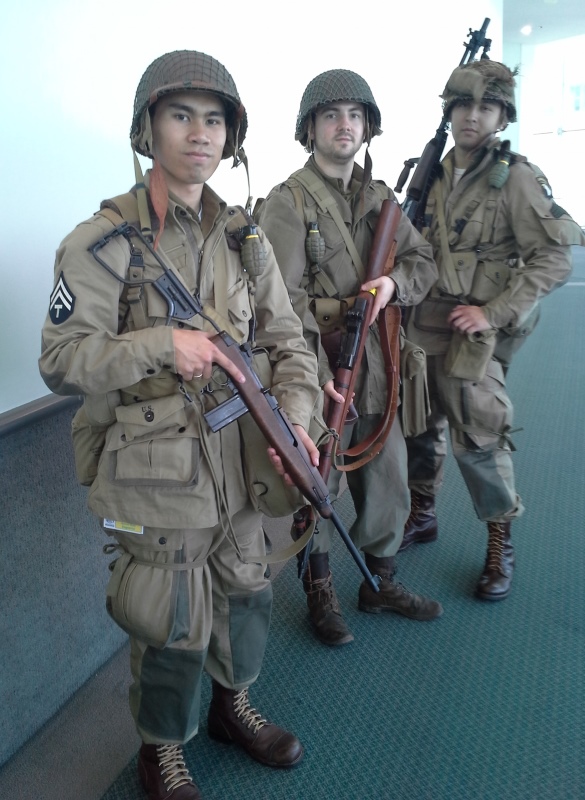

That explains the book, which is not really science fiction at all, but more of a throwback to the pulp era. The setting is the untamed planet of Wolf, whose human presence is limited to a couple of small Trade Cities. Race Cargill is an agent of the Terran Empire involved in a blood feud with his former compatriot, Rakhal. The latter is a villain of the mustache-twirling kind, though we learn this mostly by inference, as his presence in the book is nearly entirely off-screen. Rakhal had married Juli, Race's sister six years before, and then disappeared into the wilds of Wolf with her. The story begins with Juli's return, having left Rakhal for his cruelty and irrational behavior.

This incites Race to find Rakhal and end the feud, once and for all. In the course of his travels, Bradley shows us a Howardian world of degenerate humans, subhumans, violence, torture and cults. It's a savage affair, with lots of lusty prose, lurid descriptions, and bloody combat. Rough men and enslaved women. A hint of incest. I would almost take it for satire, but it seems awfully earnest.

In short, it feels like a kinescope of a television show – recognizably a copy of something, but lacking in dimension. A not-too-picky person might enjoy the book as an adventure story with only the thinnest veneer of s-f (the "Door Through Space" hardly figures at all), but said reader will be hard pressed to recall much from the experience save for, perhaps, a mild, inexplicable sense of revulsion.

Two stars.