by Winona Menezes

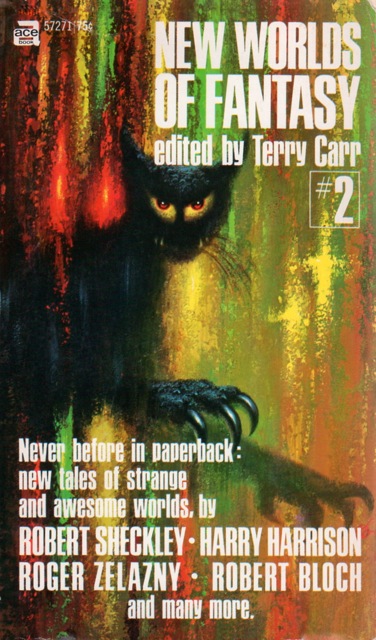

Cover by Kelly Freas

After the success of New Worlds of Fantasy, despite being almost exclusively a set of reprints, Terry Carr has put together a second fantasy anthology, including a several stories published herein for the first time. There are many unsurprising names in the list, but there are also some plucked from relative obscurity. No two stories have much in common, but all share an evocative, dreamlike quality that give the collection its sense of cohesion.

Introduction, by Terry Carr

Carr opens his anthology with a reminder of why fantasy literature deserves its place on our shelves alongside more "serious" works. He points out that human beings need to dream in order to give their brains the chance to sort through all the things that get muddled up in our heads during our waking moments. If dreams are our chance to reorient our subconscious needs and desires in sleep, then fantasy is when we do it while awake. Failing to indulge in a little escapism every now and then might result in the kind of psychic constipation that has people forgetting the importance of dreams, not that I ever needed reminding. Lest we find ourselves spiritually backed up, lets begin:

The Petrified World, by Robert Sheckley

[first appeared in the February 1968 IF]

Tom Lanigan seems to be a sensible man, but he’s been having persistent nightmares about a frighteningly immutable world. The world he inhabits is fluid, where the probability of anything spontaneously changing, disappearing, or appearing out of thin air is never zero. As Lanigan navigates an ordinary day, we see his watch change from silver to gold, his hair change from white to blue, a tree grow old and whither in the blink of an eye, a sidewalk turn to liquid, a boat sail through the clouds. One day his nightmares are realized and he finds himself on a much more stable plane of existence, but his benchmark for normalcy is his own transient reality, and this new world is enough to drive him mad.

It's disorienting how Sheckley plays off Lanigan’s capricious world as ordinary, and his dream world as a suffocating nightmare. Obviously, given his sense of humor, the petrified dream world is meant to be our actual world. But Lanigan’s perspective is given in a slice-of-life way that makes it easy to slip into the expectation that nothing could be expected to remain as it is from one moment to the next. I was sold on the dread of an invariable world for a minute even though I’m one of the poor souls who already lives here, so four stars out of five.

The Scarlet Lady, by Keith Roberts

[First appeared in the August 1966 New Worlds/Impulse

Bill Fredericks cannot talk his brother Jackie out of giving up his new car, no matter how many times it kills. The Scarlet Lady, as Jackie calls it, is a beautiful vintage car that seems to have a mind of its own. Jackie finds it running over animals with shocking frequency and accuracy, but his denial of its bloodlust continues until it starts to kill people. With his brother under the car’s spell, Bill must find a way to destroy the Scarlet Lady without becoming her next target.

I thought the story’s voice was witty, but it did drag on a bit too long. I’ll forgive it, though, because of how entertaining I found the characterization of the Scarlet Lady. This car was constantly being compared to a beautiful woman in the way that men like to describe sexy cars, curvy and vivacious and having an engine that purrs. But this anthropomorphizing became increasingly absurd the more it was used, until this car was so sexed-up that some wires crossed in my brain and I felt its urge to kill was akin to some kind of erotic desire. I don’t think that Roberts intended to make his car a literal femme fatale but he did, and I'm willing to give him three stars out of five for it.

They Loved Me in Utica, by Avram Davidson

I was impressed with how quickly this story was able to make me feel a deep sorrow for its protagonist, a once-great artist struggling to cope with aging and staying relevant in a world changing too rapidly for him to keep up. The last-minute twist snuck up on me incredibly fast. It only took Davidson a few lines to reframe the whole story so quickly and humorously that I knew immediately I would not have any trouble incorporating it into my understanding of the Western canon–a fundamental component of which is the subject of the piece. Five stars out of five.

The Library of Babel, by Jorge Luis Borges

The Library of Babel is a short journey through an infinite library, narrated by one of the librarians who have made it their life’s work to decipher its mysteries. I love Borges for his ability to dangle a tantalizing glimpse of worlds beyond comprehension in front of me, described so unfalteringly that as I read I feel as though I’m experiencing the same unknowable reality. He has a real talent at describing the indescribable, and this story is a perfect example, so five stars again.

The Ship of Disaster, by B. J. Bayley

[First published in the June 1965 New Worlds/Science-Fantasy]

Finally a proper high fantasy, elves and all. In this one the elven and troll kingdoms are waging war, and the cruel elf lord takes a sadistic delight in sinking a frail human ship. Kelgynn, the sole human survivor, struggles for survival after being enslaved. It's very trite, with the elves, trolls, and man all flat caricatures of their species. Despite all the action there are very few emotional beats to dwell on, so it just reads as a straightforward recounting of a small event in a cliche fantasy universe. Two out of five.

Window Dressing, by Joanna Russ

Marcia is a mannequin who lives in a shop window and dreams of being loved, knowing that romantic love from a man would be enough to make her into a real woman. Her prince does finally come, and he’s quite an unimpressive slob, but she doesn’t know that. His love for her does start to make her real, and she’s elated until it becomes clear that the sort of man who would love a doll makes a frightening partner for a living woman. Marcia’s story is pitiful, so much like every young girl who believes that being loved by a man, any man, will save her, that it wasn’t hard at all to guess how the story would end. I very much enjoyed her perspective, and the final lines made me laugh aloud. Five stars out of five.

By the Falls, by Harry Harrison

[First published in the January 1979 IF]

This story concerns a young journalist traversing a waterfall to interview the old hermit who lives behind it, hoping he might be able to answer his questions about the unexplainable phenomena that keep falling over the side of the falls. I’m sorry to disappoint, but I did not understand this one in the slightest. It’s written competently, and I don’t blame Harrison for my confusion, which I'm certain is my own failing. But this one will have to be two stars.

The Night of the Nickel Beer, by Kris Neville

The protagonist of Night of the Nickel Beer is a freshly forty year-old man in the throes of his mid-life crisis. He leaves his wife in bed to go on a midnight walk, and feels drawn to a small pub filled with young people living the sort of carefree life that he knows he’ll never experience again. He speaks with a beautiful young woman who flatters him enough to remind him of his glory days, but the distance in life experience between him and her is too great, and he eventually decides to return home to his wife.

Maybe its because I, like our young woman, am too youthful and beautiful to grasp what this old man is going on about, but I didn’t like this story. I understand what nostalgia is, but I am not convinced that this guy actually needed to have several beers with a bunch of teenagers to remember the meaning of life. I am also expected to believe that the protagonist heroically managing to not sleep with the teenage girl is some kind of feat worthy of my respect, which is insulting to my intelligence. One star.

A Quiet Kind of Madness, by David Redd

[First published in the May 1968 Fantasy and Science Fiction]

A young woman named Maija is approached by a fuzzy little creature in need of help while on a hunt and chooses to take it to her hut and nurse it back to health. Maija and her new pet develop a telepathic bond, and she learns through dreams that it comes from a beautiful place beyond the reach of humanity, the Land-Without-Men. Her solitary life is interrupted when an old friend comes to warn her that Igor, a brute who had tried to rape her a year prior, has come back to try to win her over. Now she must make a plan to defend herself and her pet from Igor, dreaming of reaching the land-without-men where she can live free from the threat of violence.

This was one of the best stories of the lot. I don’t believe that sexual violence from a female perspective is usually done justice in this genre, or indeed, in this medium. A lot of male writers only write from the perspective of the female victim as the object of violence, not the subject. And Heaven forbid a woman write a carnal piece a little too well, lest she be relegated to the romance bins. This story balances Maija’s rage delicately alongside her dreams of a better life, and she never feels like a mere receptacle for aggression, nor does this aggression ever go understated. Five stars.

A Museum Piece, by Roger Zelazny

[First published in the 1963 Fantastic]

After failing repeatedly to find success and notoriety for his art, struggling sculptor Jay Smith decides that he’s going to try a different approach, and actually make himself into art. After taking care to sculpt his body with exercise into an Adonis to rival any marble statue, he sneaks into a museum after closing to take his place on a podium, posing so expertly that none of the patrons realize they’re looking at an actual person. But after the lights go out again, he realizes that most of the exhibits are actually failed artists and critics who had the same idea.

The premise of Museum Piece is funny enough, but every time I thought we were done with silly revelations another statue would throw off its shroud to reveal yet another disgruntled art snob in a toga. It was absurd enough to make me feel like I was going insane, and by the time I reached the end I had to check to make sure I was still reading the same story that started with a mildly disillusioned sculptor. Three stars for all the pretentious references to classical mythology.

The Old Man of the Mountains, by Terry Carr

[First published in the April 1963 Fantasy and Science Fiction]

Terry Carr wrote this story inspired by his own life, and it does have a much more grounded feel than the rest. Ernie Tompkins returns to his childhood home in the mountains of Oregon, reminiscing about his late Uncle Dan who taught him everything about the land and filled his head with folkloric tales. One such tale was of the elusive Old Man of the Mountain, a frightening presence in the woods responsible for anything from bringing storms to stealing furniture and even killing pets. As he wanders through his old forests Ernie is shocked to come across an actual hermit who casually reveals himself to be an old friend of Uncle Dan’s before disappearing into the trees.

I didn’t need Carr’s introduction to tell me that this story was semi-autobiographical; it’s always possible to tell when a writer is describing the place in which they grew up. Everything is weighty with the kind of wonder that only children brand-new to the world get to feel. Four stars for making me nostalgic for a place I’ve never been.

En Passant, by Britt Schweitzer

Another short one; here, our hero is going about his day when his head detaches itself from his neck and falls right off onto the ground. The entire story is spent watching his disembodied head roll around trying to reattach itself. The writing was fun and descriptive, which is impressive because the action was so inane that by the time I reached the end I felt as though Schweitzer had pulled a prank on me by compelling me to read the entire pointless narration. Three stars: it was funny but I don’t think I’ll remember it very long.

Backward, Turn Backward, by Wilmar H. Shiras

Ms. Tokkin is recounting to her young neighbor the story of how, when she was thirty, she believed that if it were possible for her to go back in time and relive her adolescence there were many mistakes she now knew to avoid. But one day she woke up in the body of her fifteen year old self and a week spent as a high-school student all over again, which was enough to make her realize that the struggles faced by children growing up are as important a part of life as the challenges of any other age, and are not so easily circumvented by age or wisdom alone. It’s a fine story, but beyond the time-travel nothing much happened besides a narration of the experience of being fifteen years old, which is not something I desperately wish to revisit in my adult life, so three stars.

His Own Kind, by Thomas M. Disch

Thank goodness, we almost got to the end of this anthology without a proper werewolf. By day, Ares Pelagian is groundskeeper for a wealthy nobleman and husband to his young wife, and by night he lives secretly as a werewolf with his mate, an ordinary wolf, and their litter of cubs. As his cubs grow they become careless with the killing of large game, and Ares the man is tasked by his lord with hunting and killing the family of Ares the wolf.

I don’t think I’ve seen a werewolf story yet where both forms, man and wolf, live equally realized lives. The cliche of the hunting party sent off to slay the werewolf in these stories is tragically employed by having the werewolf in human form being sent to kill his own family. The narrator is a dryad watching the saga unfold from her tree, and she speaks with a tree-like detachment from the lives of the mobile, which adds a fun dimension to the story. Five stars.

Perchance to Dream, by Katherine MacLean

The sorry inhabitants of this story’s world pass time in some kind of shared delusion, a dream world which can be accessed by a simple directing of the consciousness. In this dream each person exists in paradise as their own ideal of beauty and youth, but their real bodies have been sorely neglected, their society in disrepair. Charlie, our protagonist, struggles to pull himself out of fantasy long enough to confront his bleak reality, and is met with indifference. The characters walk around and interact with each other in a sort of fugue which, combined with the amount of mundane details scattered throughout the narration, left this world feeling far too familiar for comfort. I don’t like how unnerving it felt, but it is very impressive how few pages MacLean needed to make me feel this world's hopelessness, so four stars out of five.

Lazarus, by Leonid Andreyeff

This is the story of Lazarus of Bethany, the figure from the New Testament who died and was brought back to life. He was a gregarious young man, but when he died and crawled forth from his tomb after three days, his loved ones noticed he was now withdrawn and sullen, keeping his gaze down and never speaking more than a few words at a time. Living beings weren’t meant to know death, and anyone who meets his eyes glimpses Death in them and succumbs to despair. People travel from distant lands to see if it’s true that a man was brought back from the dead, to see if anything can be done about his hopeless condition, to see if anyone can meet Death’s gaze and come away unscathed.

This story was unsettling in the best way. The entity of Death is one of those beyond-mortal-comprehension forces of nature, and Andreyeff does not make the mistake of describing it head-on in a way that makes it comprehensible. He dances around its edges and lets the reader’s own sense of foreboding build into dread organically. It's very Lovecraftian, the indifferent cosmological force that enshrouds our perceivable reality and drives anyone who perceives it to ruin. It's a perfect complement to the canon of the New Testament, which also loves to dance around glimpses of unknowable cosmic entities, so obviously five stars out of five.

The Ugly Sea, by R. A. Lafferty

[First published in the magazine The Literary Review, Fall 1961.]

When it comes to appealing to my sense of wonderment there truly are few ways better than some nautical folklore. The yarns that old sailors like to spin do often call into question the old man’s lucidity, but something about the ocean compels me to believe them at least a little bit.

So imagine my disappointment when I was promised a proper legend about a proper seafarer, only to be met with some adult man’s romancing of a “precocious” twelve year old girl. Of course, maybe this story takes place in a different age, with a different set of social mores. But I am reading it in this current age with my current brain, and the author’s slavering over a child, and her positioning as a dangerous siren scheming to entrap men sends a chill down my spine. Nothing about this (otherwise admittedly pretty good) narrative would have suffered for aging this girl up several years, or at least not straightforwardly sexualizing a small child. One star, Lafferty, thank you and goodbye.

The Movie People, by Robert Bloch

[First published in the September 1969 Fantasy and Science Fiction]

Jimmy Rogers is an old man who has spent his entire life flitting through the backgrounds of movies as an extra, all the while trying and failing to break into a big role. He spends all of his time now at a silent movie theater watching himself in the backgrounds of old movies alongside his young love Junie, who shared his passion for acting but was tragically killed in an accident on a set. He thinks he’s going crazy when he spots Junie in crowds of movies she was never a part of, and discovers that she is spending her afterlife drifting like a ghost between different movie scenes. I thought that this one moved slowly and that the inclusion of the entire letter Junie wrote to Jimmy was very clunky as far as exposition goes. The premise was a little bit sweet and a little bit sad, but didn’t feel like something I hadn’t seen before. Two stars out of five.

Taken in total, I do feel that this anthology did its job of loosening up some of the sediments at the bottom of my psyche. Before they've had time to settle I will have read plenty more stories and dreamed plenty more dreams, but Carr's reminder of the role fantasy plays in our minds reminds me of being a child, when the lines between fantasy and reality were more precarious. It feels good to read and dream less like a discerning adult and more like a child; I will have to do it more often.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

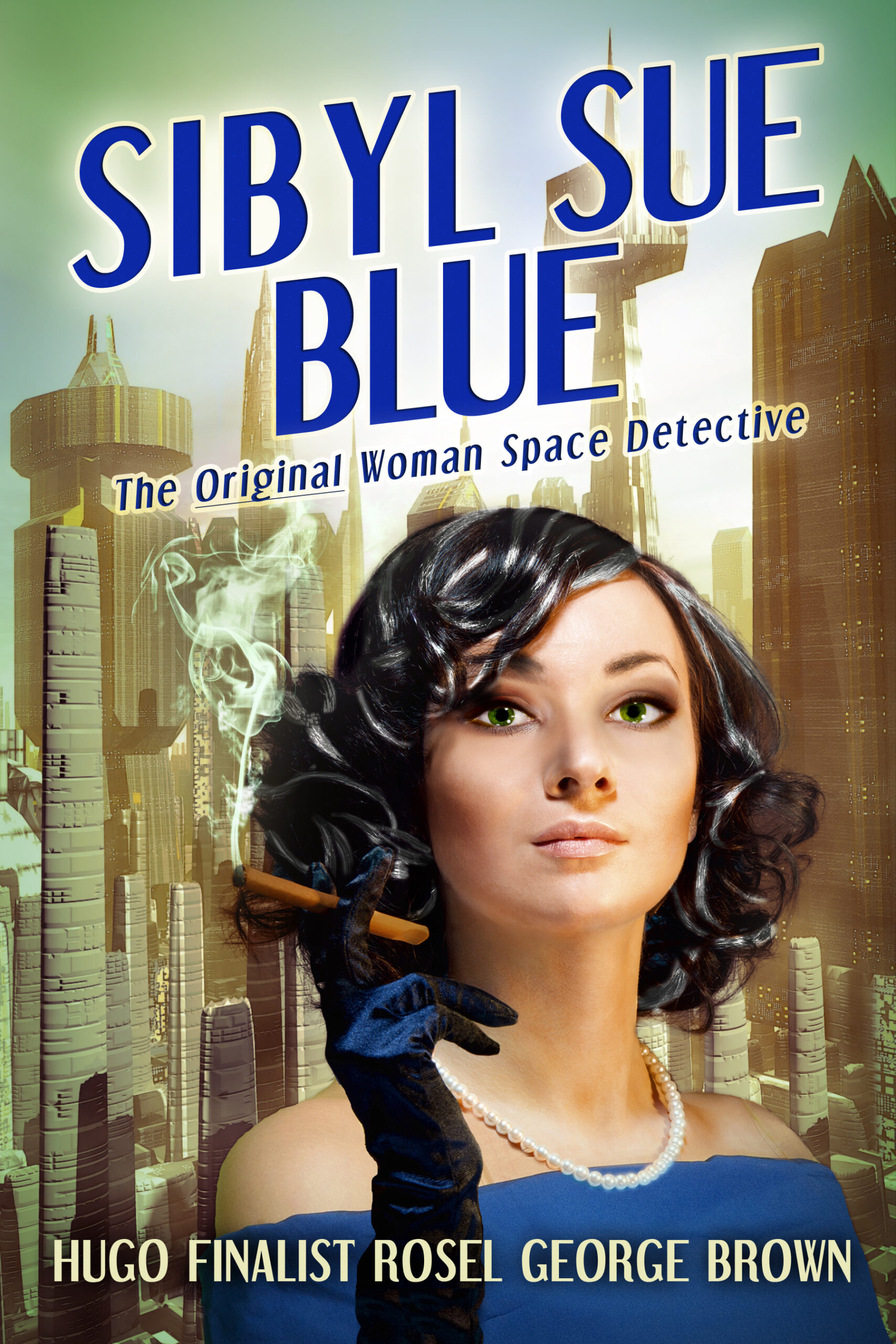

![[August 12, 1970] New Worlds of Fantasy #2](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/700810newworldsoffantasycover-376x372.jpg)

![[July 19, 1970] Dips in road (<i>Maze of Death</i>, <i>The Eternal Champion</i>…and others—July Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/700719covers-672x372.jpg)

![[June 17, 1970] Time and Again (June Galactoscope Part Two!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/frolix-672x372.jpg)

![[April 16, 1970] Junk Day for Ice Crowns (April 1970 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700420covers-672x372.jpg)

![[March 6, 1970] <i>The Waters of Centaurus</i>, <i>And Chaos Died</i>, and <i>High Sorcery</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700306covers-672x372.jpg)

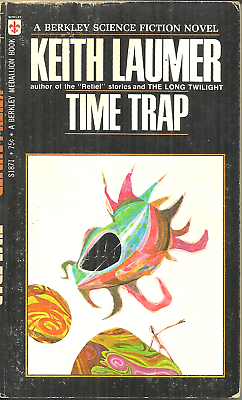

![[February 18, 1970] <i>Time Trap</i>, <i>This Perfect Day</i>, <i>Whisper from the Stars</i>, and <i>The Incredible Tide</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/700220covers-672x372.jpg)

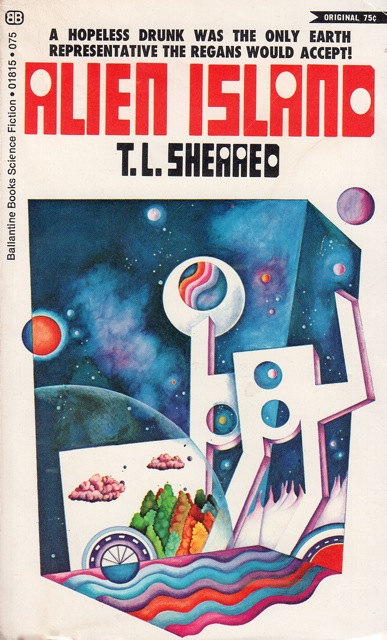

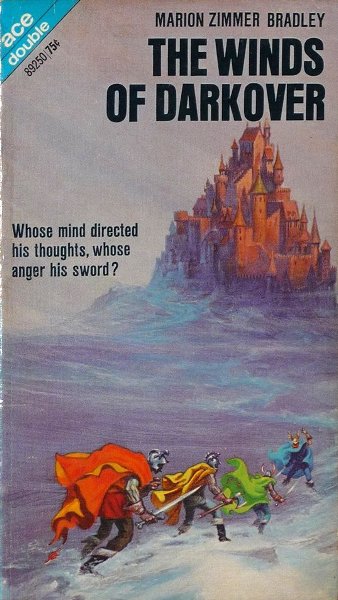

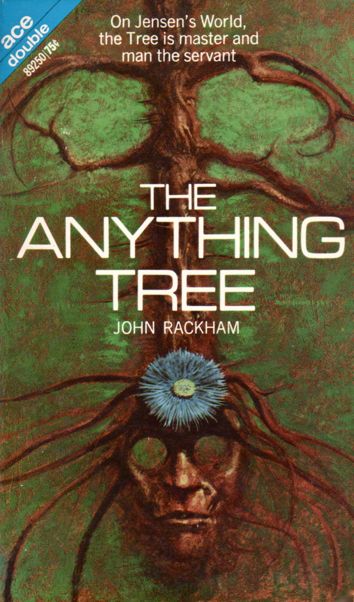

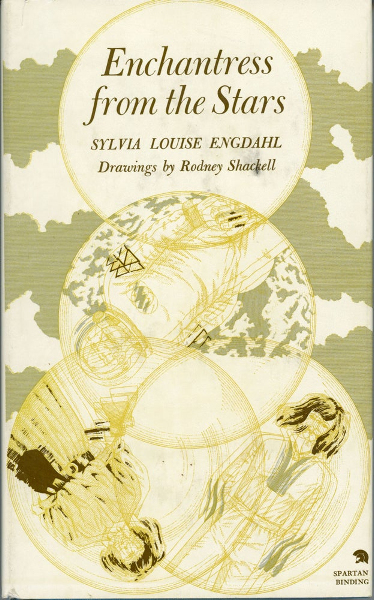

![[January 25, 1970] Alien Island, Enchantress from the Stars, The Winds of Darkover, and The Anything Tree](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700125covers-1-672x372.jpg)

![[November 28, 1969] Kurt Vonnegut Jr.'s <i>The Sirens of Titan</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/691128titanscover-672x372.jpg)