by Victoria Lucas

No.

No, no, no, no. no. I don’t believe it, can’t believe it, am not going to believe it.

Paul McCartney

Longer than the road that stretches Out ahead."

Continue reading [May 24, 1970] Let It Be (The Beatles break up)

by Victoria Lucas

No.

No, no, no, no. no. I don’t believe it, can’t believe it, am not going to believe it.

Paul McCartney

Continue reading [May 24, 1970] Let It Be (The Beatles break up)

by Victoria Lucas

OK, kiddies, the word for today is ARPANET. Well, yes, good point, it’s not a word, is it? It’s an acronym jammed into an abbreviation. But a juicy one.

I found out what it means because Mel (my husband) and I have these friends in Orinda, California (a town east of Berkeley, nice place). Sharon is more of a stand-up comedian than a housewife, who uses her housewifery–-and sometimes herself–-as the butt of her jokes. Dick Karpinski is a fuzzy bear of a man who is the first computer programmer I ever met. We don’t get to their place too often, since it’s off our beaten track between SF/Berkeley and Fortuna that we usually run on the weekends and holidays (or when neither of us has an active temp job in the Eureka area).

Richard Karpinski works for the University of California at San Francisco, supporting users of the IBM 360 and other tasks

At a recent visit, Dick was quite excited, and Sharon was complaining about her “three years of back ironing.” I don’t have much to say about the ironing, but once Dick had explained to me the reason for his excitement I admitted to some buoyancy myself. I wonder how you will feel about it.

With its initial transmission in October last year, ARPANET (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network) is the first large-scale, general-purpose computer network to link different kinds of computers together without a direct connection. Not only that, but different kinds of networks are coming online following this one. But who cares, right? I mean who of us has ever even seen a computer?

The IBM 360 with operator

FAR OUT!

Up to now you could only connect the same kind of computers, and then only by special-purpose cables and outlets in the same building, unless you could connect your computer to a "modem” (modulator-de-modulator) that converts digital (computer talk) to analog (telephone signaling) and back again when connected to your telephone line. The same protocols and hardware can connect a computer to “terminals,” boxes that can interact with a computer but do not have the smarts to actually process data. Multiple people could use the same computer at the same time (the miracle of "time sharing" that Ida Moya talked about a few years back, but again, only at the same site or by telephone. No matter what, connections were direct: point to point and dedicated. If you wanted to interact with another computer, you had to go to another terminal hooked up, directly or via modem, to the new machine.

An electronic translator of one type of signal to another, the modem

But what if you wanted to access multiple other computers from a single terminal? What if you wanted your computer to talk to another, farflung computer of a different make (ie connect an IBM to a CDC?) Here’s where Dick had to bring out his yellow pad and start writing and drawing.

Dick draws a box on his pad. “One computer, right?”* he says. “And here’s another” as he draws another box to make #2. Now you could connect a single terminal to any number of computers using a newly developed "protocol" for connection. (A protocol, drawn as lines from that word toward the boxes, is a set of rules or instructions about how to do something, and it’s above a program, which is more of a detailed list of steps to use when doing something.) Rather than using specific hardware, the protocol allows computers to "speak" a common language, over phone-lines lines… regardless of computer make or location!

As Dick, the “Nitpicker Extraordinaire,” might have written at the top of his pad (I’m a little fuzzy about how the conversation progressed), the first set of computers involved in the evolution of this network would have belonged to the US Department of Defense as part of its Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), an almost direct result of the success of Sputnik. When NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Agency) was formed in 1958, most of ARPA’s projects and funding were moved to that group. That left ARPA with high-risk or far-out projects, such as computer networking. I can't tell you which computers are involved, nor the details of the protocol (even if I understood them) because they're classified. The main reason for the ARPA network is to test the survivability of communications in the event of a nuclear war. Because if one big computer is destroyed, someone could just use their terminal to contact a different one to complete a process.

Talk to any computer anywhere, without a telephone

An ARPANET processor

While this exciting technology is limited to the ARPA for the moment, technology tends to spread to civilians eventually. Just think about it! The ARPA network and others like it will make it possible to distribute programs and data widely without printing it out and mailing it. As long as a computer can talk back, you can get and send data from and to it. Even more amazing, the initial transmission speeds showed that messages were being sent to a place 350 miles away 500 times faster than local data was traveling before. It was so fast that the initial speed caused a system crash, followed by a rebuild to handle the velocity, all during the very first transmission. It's not faster than light, but it's a darn sight better than having a computer operator working on far-out national research projects for ARPA fall asleep on his or her keyboard waiting for an answer.

What miracles could you work with a fast, smart, terminal that could connect to any computer in the world? Now that’s exciting!

*To Dick’s other friends. Yes, I know Dick, but I don’t remember any specific conversation like this. Any mistakes or misrepresentations are my responsibility.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

by Victoria Lucas

Good news!

Remember when last year (December 12, 1968) I reported that the submersible Alvin had sunk at around 5,000 feet in the Atlantic Ocean, with bad weather curtailing the search for it?

The Alvin

The Alvin

With money provided by the US Navy, whose vehicle the Alvin is, and who expected to learn whether and how such retrievals might be done, Alvin's caretakers sailed out armed with imaging tools and images, along with equipment and engineers to find and raise the submersible. They succeeded on their Labor Day cruise!

Fortunately for its seekers, the Alvin had landed on the ocean floor right side up, gaping open, so a special tool was lowered into it and remotely sprung open to hold it while it was slowly raised and then towed close to the surface back to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Great care was taken not to disturb the ocean life that had inhabited it, and that was removed and taken to labs for observation, etc.

There was one funny incident: an engineer who had been on the Alvin's host ship on the last trip before its loss and was also on its Labor Day tow ship came back (like most crew) hungry. He accepted a seafood sandwich from the welcoming spouse of a crew member, and while he was eating it a picture was snapped of him with the sandwich. Coincidentally the lunchbox left behind when the Alvin had slipped into the ocean was in the picture.

And someone interpreted that to mean that the engineer was eating the sandwich that had been in the lunchbox (along with an apple) while the submersible was beneath the waves for 9 months. Immediately there sprang up a certainty that the ocean had hitherto unknown powers of preservation. The last I knew someone was talking government grants.

Now for the main event!

No Separate Beds (Review of "Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice")

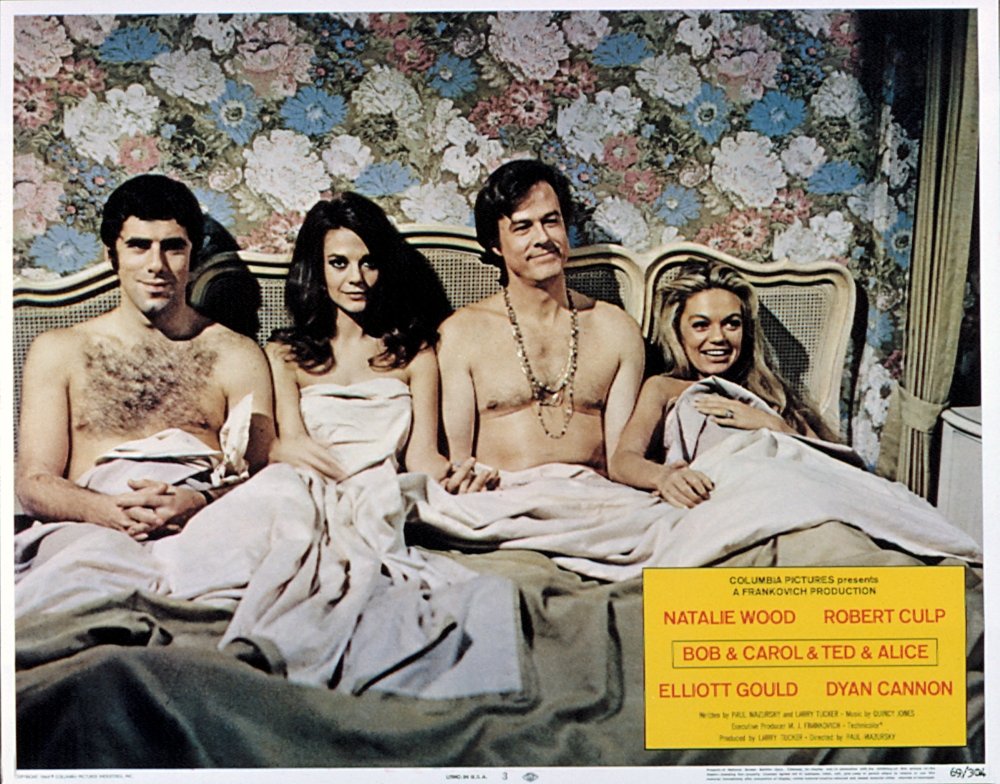

Poster showing Gould, Wood, Culp & Cannon as the eponymous characters

Well, I'll be! Someone up and wrote a film script about upper middle-class couples behaving like unsupervised teenagers. (I would have said "well-to-do couples," but that's a bit old-fashioned of me.)

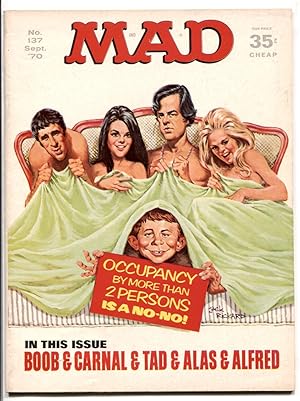

If you've seen the latest Mad Magazine (and I know some of you have) you've essentially seen the above poster for "Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice"–Robert Culp of "I Spy" resting apparently naked against the headboard of a bed with Dyan Cannon, Elliott Gould, and Natalie Wood, all covered by strategic bits of bedding. (The same artist did both the parody and the original poster.)

The MAD version of the movie poster

At the beginning of the movie, there are Bob & Carol in his sports car driving through beautiful countryside to an expensive retreat they call "The Institute" (a stand-in for Esalen, a school at the vanguard of the "Human Potential Movement"). After a dramatic group therapy "marathon" session we see them and their friends Ted and Alice, back home eating out at a fancy restaurant, living in beautiful masonry shelters (no doubt in nice neighborhoods), consulting an expensive psychoanalyst (the writer/director/producer's real psychoanalyst by all accounts), and experiencing great angst.

Is the angst political, about how many resources they're using up and how they should be giving back? Is the angst medical, cares about health, death and life? No. It's highly personal and laced with guilt. Guilt about political or family matters? No–politics are never discussed, and each couple has one child who is not the center or even (it seems) an important focus of their lives. Like them, each child is privileged and loved and free, even if spending many evenings and weekends with Spanish-speaking help rather than their parents, "extended" families such as grandparents (who probably live far away), or other children.

So why the angst? The joy in the opening music (Handel's "Hallalujah Chorus") comes in anticipation of received wisdom, which appears to them in group therapy to be the practice of honesty, and in some of those honest moments they realize that . . .

They aren't having enough sex.

But I shouldn't make fun of them. They just want what every teenager wants: the privacy and the time to explore–him- or herself as a psychological being, and him- or herself as a sexual being.

Perhaps I should be asking why it took them so long. I think we all know the answer to that: because they weren't allowed to explore when they were teenagers (although a minority of this generation did manage to be either secretive or untruthful enough to get away with it). Think of the kids you know who got married while in high school–or were you one of those youngsters yourself?

I think these wealthy adults (all four starring actors in their 30s, fitting the characters they play) were waiting for the sexual revolution now in progress. They were waiting for permission. Now they have it.

Just in case the movie isn't enough for you

So we have gone from Ricky and Lucy Ricardo sleeping in separate beds while a married couple, never showing Doris Day in bed with anyone but a voice on a telephone, and generally strict rules about how sexual behavior is suggested in non-pornographic films, to: wham! two couples in bed together—albeit just sitting there after a brief bout of playing hide and tickle.

In their innocence they call their foursome an "orgy." I wonder what the scriptwriters, Paul Mazursky and Larry Tucker would have done with the group hosting weekly orgies whose members I'm now interviewing for my book. Probably discarded us as an extreme manifestation of the sexual revolution and gone back to using improvisation (by writers only) as a tool for generating dialog (a rumored way of writing the scene with Ted and Alice in which he is horny but she is not).

The film ends with the Burt Bacharach song "What the World Needs Now." As it plays, a crowd of people practice a tool for freedom they can exercise while fully clothed, whatever they mean by it, "love." But wait! There's still the book!

This is a comedy without very much laughing out loud. If you are not offended by the very premise of it, I think it might amuse you. I give it a 4 out of 5 mainly for excellent comedic acting and witty writing.

by Victoria Lucas

A Busy Time

These reviews are very late what with all this moving, looking for a place to buy/live, and working as temps when my husband Mel and I can in Humboldt County, California (with nearly weekly trips to the San Francisco Bay Area). Still, maybe you won't have attended/heard about the reviewed subjects, so perhaps they will still give you some information you didn't have before.

I think I'll start with the concert, since if you hang this up I'd rather you do it when I'm nearly done–and the second review is of a book that is controversial to say the least.

Electronic Music!

Another use of the Art Gallery space

First, John Cage was not present at the concert of his work "Variations VI" given at Mills College (Oakland, California) on January 16. It was unusual in so many aspects I hardly know where to start. I guess the physical space is as good a place as any. As you may or may not know, Mills has a perfectly good auditorium that they regularly use for music. This wasn't held there. It was in an art gallery that had absolutely nothing in the space except: (1) some pillows, (2) synthesizers and other electronic gadgets, (3) long tables in a square to define a central performance space, and (3) what seemed like hundreds of patch cords draped over rolling clothing racks.

This is why the racks of patch cords–the Buchla 100 Series

Walking into this space was like visiting an alien landscape. It was like no concert I've ever seen before or since. Although Cage was not there, his collaborator David Tudor was, along with other electronicists. People (audience) were lining up along the walls around the performance space, some sitting on the floor. The pillows were taken. The floor was too hard to spend the entire concert sitting on it, so Mel and I wound up walking around as the musicians performed.

Pioneers of a New Musical Frontier

David Tudor, electronicist

Sometimes many performers were playing, sometimes a few. Knowing Cage's compositions, we could have predicted that there would be many silences. Sometimes there would be only one sound from one synthesizer or other electronic or electrical device, surrounded by silence.

I would not have known the Buchla 100 ("Music Box" above) had I not seen it before. I don't remember exactly when, but it must have been in 1965 I was hanging out at intermission in the tiny lobby of the San Francisco Tape Music Center on Divisidero and noticed that composer Morton Subotnik was standing near a small table they used for taking cash and dispensing tickets, then empty. A man I had never seen before came in with something under his arm that he deposited on the table. It looked like one of the two modules shown above, like a tiny telephone switchboard but with something like a keyboard showing.

I remember that I was close enough to hear the man carrying it (turned out to be Donald Buchla himself) explain that the metal strips that looked like keys did not depress but responded to a hovering finger. The expression on Subotnik's face was priceless, and I remember that he literally jumped for joy. I later learned that this meeting constituted the delivery of a piece of equipment commissioned by Subotnik and Ramon Sender of the Tape Music Center and paid for ($500) by a Rockefeller Foundation grant.

I know, I'm weird, but I enjoyed the music in the gallery tremendously and hungrily watched the patch cords as they were deployed on different instruments by different performers. Tudor was the only one I could recognize in the mix of (mostly) men dodging back and forth from the hanging cords to the instruments. Here is the list of performers from the front of the program: Tudor, Martin Bartlett, Charles Boone, Anthony Gnazzo, William Maraldo, Edward Nylund, Judy Ohlbaum, Ivan Tcherepnin, and Ron Williams. Unfortunately for those of us who are mad for tape and electronic music, the instruments were not identified.

The Future of Music

I tell you all this, because music is changing. Although I don't expect much change (especially for some years) in traditional orchestras, some part of musical performance won't ever be the same again. The Moog synthesizer and Buchla Box (for instance) on display at this concert are prototypes of instruments of the future. The future ones won't look the same, because these are too hard to play as they are if you aren't an electronics engineer. (Hence the patch cords–on most there are no keys that depress, no place to blow, nothing to bow or pluck.) At least some of the music of the future will be very different, but I'm sure I will still enjoy it. This music in this performance? 10 out of 10!

Book Review of an Illicit Pamphlet

On to the second review, of a book by poet Lenore Kandel that has been out since 1966. It's very hard to obtain, because it keeps getting confiscated by police as obscene. Unlike some religions, our Protestant Christian variety has no place for sacred sexuality (although Kandel read some excerpts from Roman Catholic mystics at her trial).

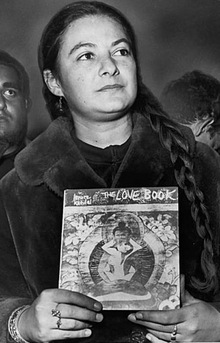

Lenore Kandel with Her "Book"

Her The Love Book is a small pamphlet of poetry (8 pages of 4 poems) that treats religious sex seriously ("sacred our parts and our persons"), using some ordinary and some made-up words, but also many words and phrases that are believed to be anathema to polite society because they do not disguise the activities they extol.

What can I say about these well crafted turn-ons that I finally managed to find for sale? Only that they harm no one, are meant for adults, and display a reverent, eccentric beauty. Since Kandel's tiny paper booklet started being repeatedly ripped off by the authorities, sales have increased anywhere the book could be found. Kandel's reaction? In thanks to the representatives of authority, she contributes 1% of her proceeds to the Police Retirement Association. As for this book–like the music, once I was able to get hold of it I experienced it as 10 out of 10 for its rare, raw, honest description and exaltation of feelings.

I hope myself to have a book of transcribed interviews on female sexuality coming out, but it might not be for a year or two. Maybe I'll need to get a guest to review it for me.

Toodle-oo till next time,

Vicki

by Gideon Marcus

Robert F. Kennedy is dead.

I wasn't even a fan of Kennedy, not really. Until last week, I'd regarded him somewhat with disdain. After all, he'd stayed out of the presidential fray until Senator Gene McCarthy had cleared the way, jumping in as if to steal his lunch. He had none of the urbane wittiness of his late brother, looking rather like a bad caricature of Jack Kennedy.

But as I followed the race, I came to develop respect for the man. The newspapers did not cover his speeches in depth, for RFK's speeches were about policy, and policy is boring. I like, policy, however. I like a candidate who lays out his priorities. I like a candidate who appeals to the most downtrodden of Americans, who risks being branded a rabble-rouser or "dangerous" in his efforts to bridge the race gap.

And he clearly was resonating, from his surprise victory in Indiana, to his follow-on win in Nebraska, to his narrow loss to McCarthy in comfortable, suburban, white Oregon.

Bobby came to San Diego last week. I think McCarthy was here, too. Kennedy talked of uniting their efforts against Humphrey to take the country in a new direction. McCarthy responded, per my local newspaper, that he prefered to go it alone and see what happens.

Well, McCarthy's gotten his wish, though he can't be happy with how it happened.

I did not vote for Kennedy in last week's primary, but I would have cheerfully voted for him had he survived to win at the convention. I did not dwell overmuch about Kennedy before last week. Now, I cannot think of the man without blinking away tears.

He did not deserve to die. This is the fifth time in six years that an assassin's bullet had cut down a hero in his prime (JFK, X, Evers, King, and now RFK) At this point, I'm not sure how much more we can take. As President Johnson tearfully said in a nationwide address last week:

"Let us, for God's sake…put an end to violence and to the preaching of violence."

by Victoria Silverwolf

It has happened again.

Robert Francis Kennedy, Senator from the state of New York and Presidential candidate, was pronounced dead early on the morning of June 6, a day after being shot multiple times after speaking to supporters in the Embassy Ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, California.

The candidate addressing supporters not long before the murder.

Political assassinations are supposed to be something Americans read about in history books. Lincoln, Garfield, Mckinley. Those of us who were around three decades ago may recall the murders of Mayor Anton J. Cermak of Chicago and Senator Huey P. Long of Louisiana. Old news, or so it seemed just a few years ago.

President John Fitzgerald Kennedy: November 22, 1963.

Malcolm X (El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz): February 21, 1965.

Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr.: April 4, 1968

Only two months after the latest of these atrocities, we once again have to ask ourselves why such horrors plague us so frequently.

I should feel sorrow. I should feel rage. No doubt I will experience these emotions very soon. Today, I am numb.

Perhaps it is best if I end with words spoken by Kennedy himself, on the day Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr., was murdered.

Senator Kennedy announces the death of Doctor King to a crowd in Indianapolis, Indiana. Some claim the wise and gentle words of this impromptu speech kept the city from exploding into violence.

What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness, but is love, and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black.

by Victoria Lucas

The Real World Invades the Land of Make Believe

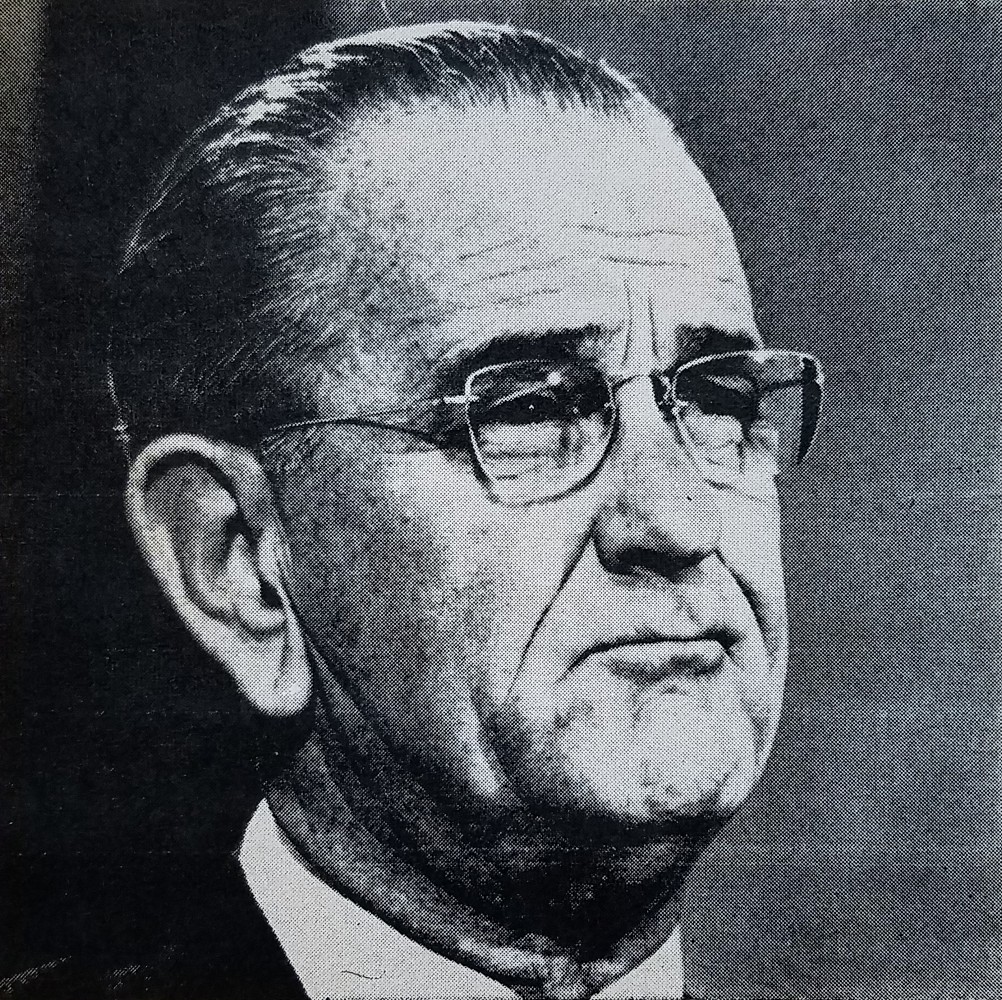

In case you haven't been watching children's TV lately, Daniel Striped Tiger is Fred Rogers' sock-puppet alter ego that he voices for his Misterogers' Neighborhood PBS program and public appearances. Daniel is mostly seen in the show's make-believe section that Rogers carefully distinguishes from the "real" parts of his "neighborhood" to help children understand the difference. But sometimes the real world enters the inner world of Lady Aberlin (Betty Aberlin) and King Friday XIII (another puppet), as it did earlier this year when an anti-war protest happened in this part of the show (as reported by me in this piece).

Lady Aberlin Comforts Daniel

A nose rub helps

After Daniel gets another worry off his chest about whether all the air could go out of someone, making them cease to exist, he gets to the real concern bothering him. He asks his friend Lady Aberlin what "assassination" means. "Have you heard that word a lot today?" asks Lady Aberlin. The answer, as you can imagine, is "yes." His friend defines the term in words a child could understand, and soon attempts to move on and talk about a picnic two other denizens of the make-believe world are about to have. But Daniel is too sad to go to the picnic–very uncharacteristic of this childish, sensitive, and highly social character.

Rogers Will Speak Frankly Tonight

In another uncharacteristic move, NET has announced a half-hour prime-time special this evening for Rogers to speak–not, as he usually does, to children, but to adults, and specifically to parents, about caring for their children during this trying time. Although I don't have children (yet), I want to learn how to be sensitive to the needs of our friends' little ones.

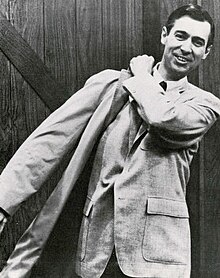

Fred Rogers

And I don't know about you, but I'm going to try to find a neighbor with a TV who wants to watch tonight, since Mel and I still don't have one of our own. I can hardly think of anything more soothing than the voice of Mr. Rogers, speaking slowly and deliberately, attempting to comfort and inform. In the meantime I will be thinking about Bobby Kennedy and how excited I was looking forward to voting for him.

Bobby Testifying

Rest In Peace, Mr. Kennedy. I think history will treat you kindly.