By Ashley R. Pollard

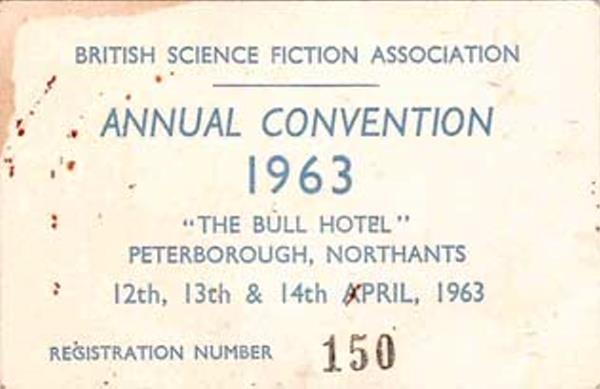

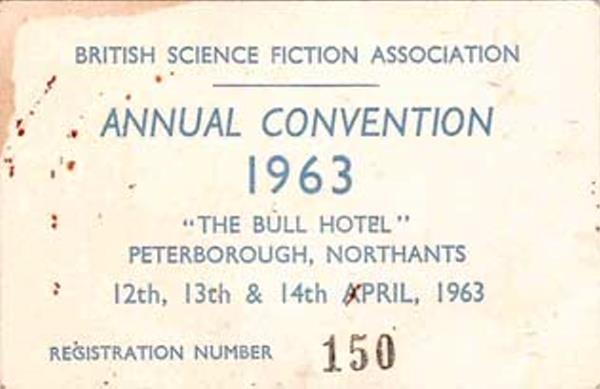

BullCon, was the 14th British Eastercon held this year in Peterborough, and as usual a celebration of all things fannish. British Eastercons are, as the name suggests, held over the Easter weekend (though in days gone by they were held over Whitsun holiday weekend). And, despite being the national SF convention, they are independent events run by fans.

I was, for the usual reasons, unable to arrange travel to attend, but I was able to rely on my friend, Rob Hansen, who compiled the reports of those who attended.

This was a big convention, with over a 130 fans in attendance. Not the biggest Eastercon on record, but up from last year's 94. All things considered, this seems to be an indicator of a healthy interest in science fiction and fantasy. An added feature of this year's convention was the presence of a film crew, who were covering the event for local and national press, and recording interviews with the authors and artists for television and radio.

How glamorous!

BullCon was also the fifth anniversary of the BSFA: the British Science Fiction Association. As you may remember, money was raised at last year's convention to create an award to honour Arthur Rose "Doc" Weir, who before his death had been the secretary of the BSFA.

The Doc Weir award will be given annually to recognize someone who has contributed to fandom, but who is otherwise unsung. The quiet fan who goes about doing the necessary work that keeps things running, and this year I can happily report that the cup was awarded Peter Mabey.

Peter, is a member of both the Cheltenham Circle, the BSFA, and a founder member of the Order of St Fantony, which became known to fandom at large in 1957 at the British Worldcon. Like all things fannish, the description of the group depends on who you talk to: secret Masters of Fandom; a group formed to greet Americans who came to over the pond; or a cringeworthy jape: a fannish practical joke.

Whatever position one takes I'm sure the Order of St Fantony will be around for a number of years. Anyway, regardless of fannish sensibilities, well done Peter. I hope you get to to many more conventions in the future.

Like all large fan run events, there were issues with the time the events were meant to start versus the actual time they did start. Not unsurprising given the size of the hall used for the main events and the quality of the public address system.

So the good/bad news is that next year the convention is again being run in Peterborough because the hotel management liked the fans so much it invited them back. The bad news is the cost of eating in the hotel. For those who plan to attend next year, the best eateries are either the Minster Grill or fan favourite The Great Wall Chinese restaurant.

Moving on, Ken Slater opened the convention and introduced Brian Aldiss who then went on to interview some of the guests of honours before the BullCon program proper started.

With humour and charm, Brian introduced on Saturday morning the Guest of Honour, the incredibly handsome Edmund Crispin, which for those who don't know is a pseudonym of Robert Bruce Montgomery. Our guest of honour also admitted to being a member of the BSFA, making him one of us.

His talk was titled, Science Fiction: Is it Significant?

The argument presented started by saying that SF genre certainly considers itself significant and or feels it's important to be seen as significant. Especially in these times where mankind is taking its first steps into space and towards the stars. However, he saw a danger in this because of the risk from being absorbed into mainstream literature. He referenced crime fiction in the early thirties, to create a parallel for what happens when everybody starts writing in a genre they don't fully understand.

His second point led onto mainstream authors who have produced the occasional work of SF that were in his mind poor, for example, On the Beach by Nevil Shute. His argument being that mainstream authors didn't understand the problems and conventions of the genre. And this led to second-rate SF stories and the genre being labelled as bad.

His third point was the influence of television.

Here he was quite scathing saying, "there is little differentiation between merit and lack of merit." In his opinion, the presence of aliens or spaceships is the only factor to differentiate TV SF from conventional moribund mundanity that is transmitted over the airwaves.

Mr. Crispin's fourth point was an observation that the idea of the cosmos had permeated the common culture, as evinced by the fact that even the Astronomer Royal had stopped saying traveling into space was foolish science fictional fantasy. Which raised a chuckle at the inability of the British establishment to keep abreast of the times.

Finally, he drew his talk to a close by arguing that in SF, space travel is presupposed to be a fact or matter of course, not a theme in and unto itself. He observed that SF authors crammed ideas into their short stories that would fill a novel in in other genres. As an aside he said, "SF authors are generally underpaid," which raised a cheer of "Hear! Hear!" from author Harry Harrison.

He finished his interesting talk with a couple of observations. The first that readers do not like to be told that people are unimportant, and that SF is a major revolution in the evolution of literature since the time of Shakespeare and Marlowe.

A question-and-answer session followed Mr. Crispin's talk, which touched upon the debasement of the SF genre in the eyes of the general public by mainstream writers.

The rest of the day was equally lively. For example, one panel featuring a discussion about censorship, with an interesting number of anecdotes from the large number of SF authors in attendance.

Saturday evening was enlivened by the presence of a four piece band and the Fancy Dress Party. The award for Best Monster went to Harry Nadler. Janet Shorrock received a special prize for dressing up as a cat girl. This year's convention theme was "After the End," so I shouldn't be surprised that Tony Walsh won first prize for dressing up as a sandwich-board-man with the slogans front and back, "Prepare to Meet Your Beginning" and "The Beginning is At Hand." Some took their costumes out onto the streets to delight/scare the nonfans.

Another tradition at the Eastercon is the art competition.

This year the best colour work was won by Jack Wilson, runner up was Terry Jeeves. Eddie Jones won the award for the best black and white artwork. Terry Jeeves also garnered the award for best cartoon. And, the backdrop used in the main hall, created by Marcus Ashby, was highly commended for contributing to the atmosphere that made the convention a success.

Parties. There were a few. One, run by Ella Parker and Ethel Lindsay attracted 53 people. All crammed into one small hotel room. Allegedly, Harry Harrison caused a blast as he was forced to the floor but managed to keep hold of his drink. Or so the story goes — the magnitude of the event is magnified in each retelling.

Sunday, besides the usual hangovers, the convention had a talk about the future of TAFF: The Transatlantic Fan Fund, presented by the current administrator Ethel Lindsay, with the support of Ron Bennet and Eric Bentcliffe. A detailed discussion of the finances and cost were covered and whether reports were mandatory; it seems they're not. But my feeling is that they are expected, and as we say over here, better late than never.

This was followed by the fifth anniversary AGM of the BSFA, where the chairman Terry Jeeves described the work and achievements of the organization over the last year.

There were two major crises. The first when the editor Ella Parker had to give up her post. The second when the BSFA had to move the library to Liverpool. Terry gave credit to all those whose hard work had carried the BSFA through this difficult time.

New members were being encouraged to join the BSFA. When someone asked how, Brian Aldiss is reported to have quipped, "by thumbscrew," thereby cementing his reputation for being funny.

The Pro Panel was a special event this year due to the number of professional authors in attendance. The first four speakers took a couple of questions from the audience, then tagged two other authors to come up and take their place. The authorial equivalent of a relay teams.

First question: how do you write?

Harry Harrison makes notes when writing a short story, but novels involve long correspondences between him and his editor; Michael Moorcock said ideas often took up to two years going around in his mind before he wrote the story; Edmund Crispin reported that he tried to keep regular hours of 09.30 to 12.30, writing in long hand on lined paper.

Generally, he failed and by 11.30 he gave up and went to the pub. Clearly another "funny" guy.

Next a question was asked about sequels.

Harry Harrison responded that if a book is written "right" it doesn't need a sequel (of course that begs a definition of what is meant by "right"); Brian Aldiss' cryptic comment was, "for those in peril on the sequel;" and Edmund Crispin's opinion was that there are occasional exceptions to the rule about sequels (which, I infer, is don't).

Then the panel was asked a question about Russian SF.

Kingsley Amis stated that Russian SF lacked action driven by crisis because, "in a well-planned, well-run economy one does not find crises." He told of Soviet stories in which aliens are intelligent and therefore socialist; Max Jakubowski, with, what I imagine, the benefit of having a Russian-British and Polish heritage, gave the pithy answer that Russian SF "is very heavy;" John Carnell drew parallels with early German SF; while Ken Bulmer and Mack Reynolds both spoke about about the importance of background in SF.

This was a very thought provoking panel, which ended because time had run out. See my comments earlier on program problems.

Finally, the official programme was brought to a close with a film show. This year two films were shown.

The first was Jean Cocteau's Orphee with English subtitles. This was followed by Fritz Lang's Metropolis that was allegedly last shown at the Royal Hotel Festivention in 1951. I say allegedly, because while it had been planned to be shown, the distributor instead sent a copy of the 1925 version of Lost World. Much hilarity ensued because Arthur C. Clarke ran the gramophone record player providing music to accompany the the dinosaur action.

So, watching Metropolis is considered a tradition, but in British SF fandom anything done more than once (even if the first time is a non-event) is considered a tradition.

It's also a British tradition for fans to provide sarcastic commentary on the acting of silent movies. Depending on one's mood or level of inebriation, this can be tedious or exhilaratingly funny. Funny things, traditions.

Lots of other stuff went on during the weekend, but the best thing that can be said about the event was the feeling that it could've gone on for longer, and let's do it all again next year. I'm sure Ethel Lindsay will agree, as she was inveigled into running next years programme.

Anyway, next year I hope to attend the Eastercon. We shall see if I manage the trip next time!

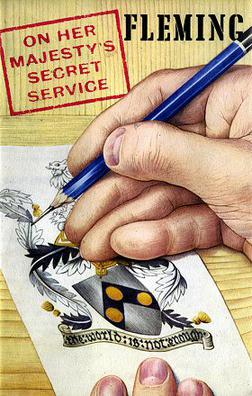

![[September 3, 1963] An unspoken Bond (Ian Fleming's <i>On Her Majesty’s Secret Service</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630902OHMSS-cover-252x372.jpg)

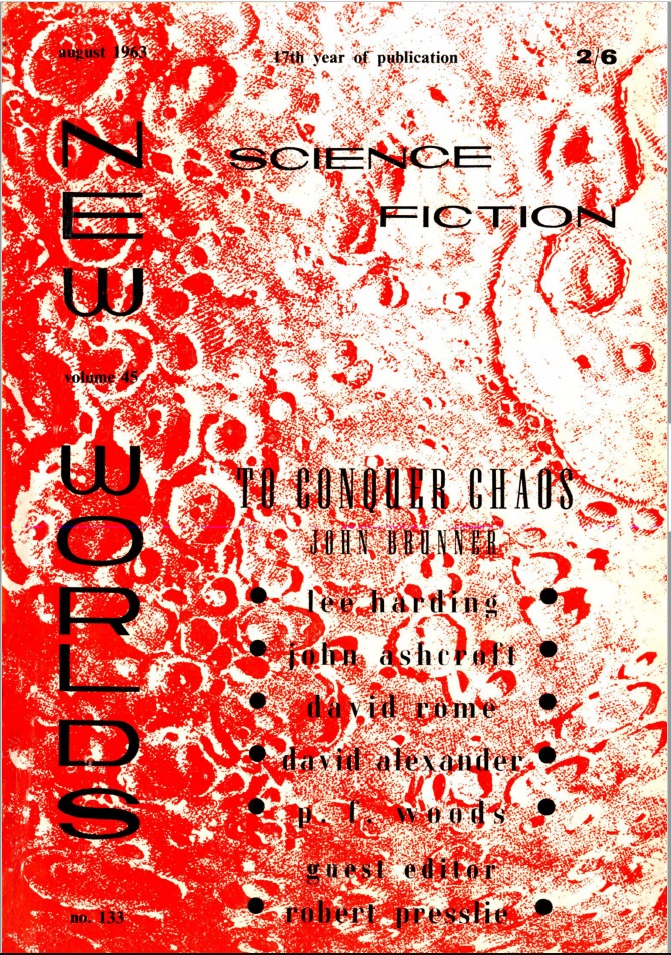

![[August 27, 1963] Ups and Downs #2 <i>New Worlds, September 1963</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/630827cover-409x372.jpg)