by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

Arthur Sellings Double Feature

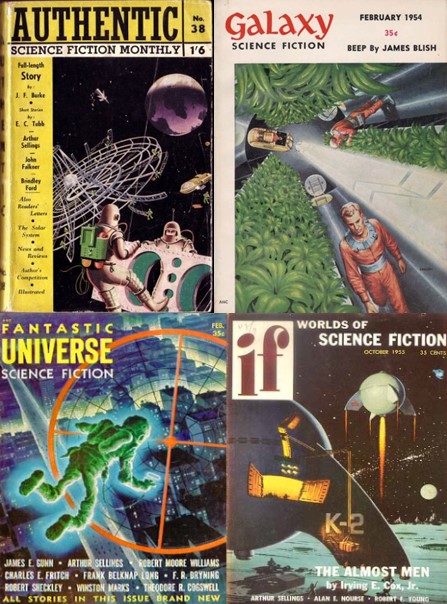

I was sad to read in last month’s Science Fiction Times of the death of Arthur Sellings at only 47. His is a name not well known enough outside of the UK.

His story follows the standard pattern of many of the current crop of great SF writers. He began at the start of the 50s magazine boom, being published first in the British magazine Authentic in 1953. He then became a regular contributor to H. L. Gold’s Galaxy, going on to appear in many of the major US publications.

As the magazine market contracted, he was concentrated largely in the British publications of Carnell and Moorcock, but also branched out into paperback novels.

In spite of getting well reviewed works coming out of Ballantine and occasional appearances in Pohl’s various periodicals, most SF fans across the pond would probably have no recollection of the fellow. His death marks a double shame as he was as prolific as ever and British writers, finally, seem to be getting more acceptance in America.

Yet it should not be thought he was a Moorcockian New Waver. Seven months before Ballard published his famous Which Way to Inner Space? in New Worlds, Sellings used the same editorial column to suggest his own vision to save SF, entitled Where Now?. Here is an extract:

The Next Revolution…is a return to roots…I am certainly not advocating a return to the rudimentary kind of s-f in which a professor holds up everything for two or three pages, while he explains it all to his idiot daughter…But a story should be intelligible – in itself – without reference to any other…Science fiction has become too glib. That sense of wonder is the prime thing which s-f can offer to the new-comer. If it doesn’t that is one more reason for him to turn away.

….Earth Abides, a ‘simple’ story on a theme as old as Noah. Yet it was new – and just as compelling for the fan as for the general reader…All the basic themes can similarly and profitably be investigated.

So, what has that meant in practice? Well, his best works have often dealt with familiar ideas but trying to consider *how* this might play out to an ordinary person. Silent Speakers looks at how having some limited telepathy could affect an individual, much in the manner of Wells’ Invisible Man, whilst The Last Time Around, uses the time dilation effect to look at how the traveller into the future would struggle to adjust to social changes and maintain relationships.

This year he released two of his best works, a short story collection and a novel. So, let's pour one out for Arthur and dive into his books:

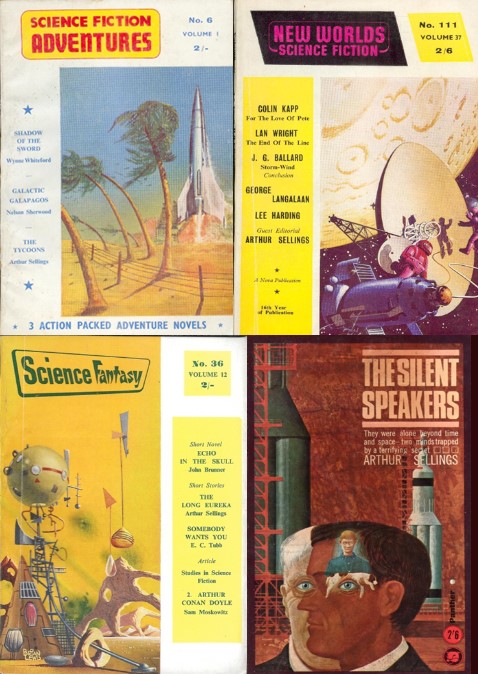

The Power of X by Arthur Sellings

In 2014 “Plying” was developed, the ability to duplicate an object exactly by taking it out of the fourth dimension. Although it could not be done infinitely, this created a large secondary market for Plied paintings, where someone may pay higher amounts for an original in order to make their money back via Plying twelve copies. Of course, the process is expensive and highly regulated.

Four years later, Max Afford, the new owner of Gallery O, discovers he has the unusual ability to detect whether or not a painting is Plied by touch. This would have turned out to be little more than a curiosity if it wasn’t for him being invited to meet the President of Europe…only to discover he is just a Plied copy of the original.

Everyone tells Max that it is not scientifically possible, yet he can sense it has been done. Who could do such a thing? And why?

Around 30 years ago Walter Benjamin wrote The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Last year, Andy Warhol created 10 portraits of Marilyn Monroe through mechanical printing. So, whilst “Plying” may not be quite available today, the questions being grappled with are contemporary ones.

This work touches on the nature of reality, what is lost when something is duplicated and the aura that we have around certain objects. These are heady subjects, but Sellings displays his usual skill to make them understandable and fit them into a science fictional framework without it descending into a word salad of gobbledygook.

At the same time, it is a well-paced conspiracy thriller that does a wonderful job creating the world of a 21st century united European republic. As you are quickly going on with the plot, someone will give away they are from London by using the metric system in East Anglia, where the locals generally do not. The feel is closer to The Great Escape than 2001: A Space Odyssey.

It should also not go unnoticed that Sellings has a wonderful turn of phrase, and some parts are deliciously funny such as:

The ‘package’ must be something special, or she would have simply brought it in to me. What was it? A three-ton hunk of concrete by Harold Bleckstein? He was in the middle of a three-ton concrete period just then and had an artist’s fine disregard for such small details as phoning to let you know the latest was on the way.

Or

‘Not a patch on that brewery, was it, Ada?’ I don’t know what they had expected. Free samples?

Add into this multiple fleshed-out women characters and some very progressive attitudes on display and I am more than happy to give this a full five stars.

The Long Eureka by Arthur Sellings

His second short story collection covers from where the last one left off, in 1956, going up to 1964, along with a couple of originals.

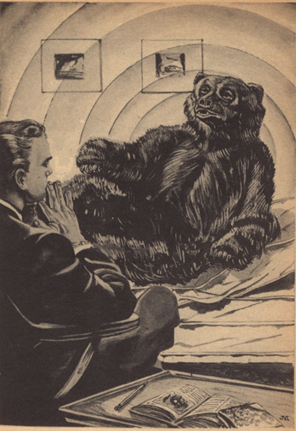

Blank Form

Originally published in July 1958 Galaxy, Sellings tells of Fletcher, a psychologist who believes he has run down a man with his car. It turns out that the victim is not only uninjured, but is actually an amnesiac shape-shifter. Being a psychologist, Fletcher does not wish to hurt or profit by this fellow, but to help him.

This is a perfect example of what Sellings does so well. Take a standard SFnal concept and bring it into a much more ordinary mode, looking at how different people might react in an uncliched manner. The ending feels a bit incomplete but still a strong tale.

Four Stars

The Scene Shifter

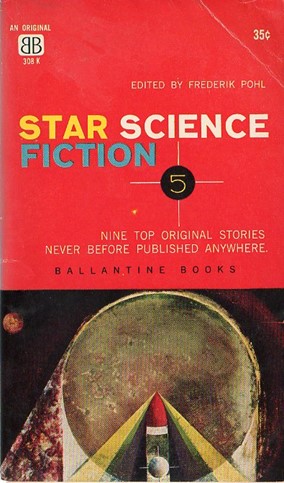

Possibly the high point of his American career. This story was published in Star Science Fiction #5, between Daniel F. Galouye & Rosel George Brown.

When actor Boyd Corry goes to see one of his films, he finds it has been changed from a drama to a broad comedy. Soon it happens again, where an ordinary romantic comedy is changed to pornography. These shots were not filmed and the reels themselves have not been tampered with. What could be causing this?

At first this seems like a slight tale about the movie industry, something of a piece with The Time-Machined Saga, but it evolves into something deeper. It looks at the relationship between the audience and the picture, asking who really has control of a story.

Four Stars

One Across

Jumping back to earlier in Selling’s career, One Across was originally published in May 1956’s Galaxy.

Norman is addicted to crosswords, doing more and more challenging puzzles. In the most fiendish puzzle yet, he discovers it can only be solved by utilizing four dimensions. This realization causes him to be transported to another dimension, a desert plain inhabited by people who have solved complex problems. They are building a utopia and need him for one purpose, breeding.

This does feel like it is from a writer’s earlier career, more what you might see turn up in an If First. It has a good style and some interesting ideas but none of them are properly explored.

Two Stars

The Well-Trained Heroes

Now for a more recent piece, covered by the Journey in the review of Galaxy June 1964. Our esteemed editor synopsized it well , so I am not going to be repetitious.

We are also in agreement in our thoughts on the story. The central concept, a kind of reverse The Space Merchants, is a good one, but the story is too long and rambling, with the decision to make it told predominantly through dialogue making it all far too expository.

A low Three Stars

Homecoming

In this previously unpublished work, Sellings once again makes use of an amnesiac. Sam Bishop wakes up after a car smash with only the vaguest memories of his life. Having lost his legs in the accident, Sam finds himself growing restless without a job. And, in spite of how nice everyone in Greenville seems, he can’t help but feel something is wrong.

Whilst using what would seem to be a Twilight Zone style of setup, we get a much deeper exploration of a host of ideas such as, how we treat the disabled, what the difference is between reality and illusion, what really is a home?

A high Four Stars

The Long Eureka

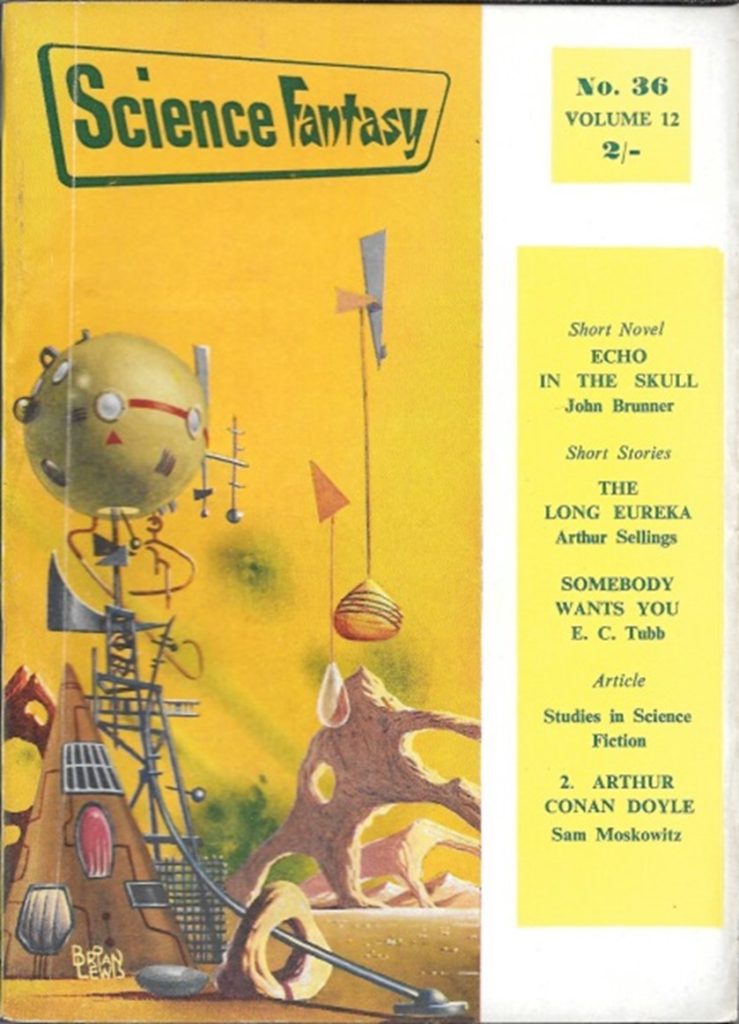

Back to reprints, where the titular piece comes from August 1959’s Science Fantasy.

In 1820, Issac Reeves believes he has discovered the Elixir of Life. Unfortunately, no one believes him, in spite of the fact that he doesn’t seem to age. Convincing anyone else is going to take a very, very, very long time.

I have a soft spot for longitudinal tales of immortals, so this fitted right into my wheelhouse. Also, it manages to be both funny and tragic as Isaac struggles in vain to get anyone to believe him, with each successive generation having a new explanation for his claims.

Four Stars

Verbal Agreement

Returning to Galaxy once more, with this story from September 1956.

Humphrey Spink is a poet in the 22nd Century, struggling to come up with something new to say. Seeking to broaden his horizons, he accepts a very curious job offer from Cosmic Developments Inc.: to try to find out how to purchase from the Vernans, a telepathic species that only have disdain for Earth’s technological progress.

This one of the many tales of the time trying to demonstrate an alien race totally different from our own, but it is a good example of the theme. Not a classic but enjoyable.

Four Stars

Trade-In

The other original tale in this collection is Sellings taking on robotics. When a newer robot model comes along to replace them, each robot has twenty-one days to find a new owner. The problem is, who wants an outdated creation?

This is a very affecting story giving real humanity to our creations. These armies of unemployed robots remind me of the great depression, where so many people needed work but could never find any. It brings the metaphor right back to its earliest roots and gives us a fascinating solution for Davie by the end.

Four Stars

Birthright

And finally, one of his first stories for New Worlds, from November 1956.

Farr finds himself in a white room tended by gods of metal. At first, he is hostile towards them but, eventually, he agrees to learn from them. Following his educational journey, we learn of his people’s origin and the purpose the gods have for him.

This is definitely a more experimental and controversial piece, with lines such as:

I anger again. God is evil god I hate god. I smash god face again.

At the same time, it touches on a number of thorny issues and delicious concepts. By the end I am not sure where I stood on any of the character’s choices, and it is all the better for it.

Five Stars

Hic jacet Arthurus, auctor quondam et auctor futurus*

So, there you have it. I hope I have shown he was a brilliant writer who has yet to have the full appreciation he deserves. Hopefully, like his legendary namesake, his reputation will rise in SF’s hour of need.

*Apologies for the bad Latin.

by Gideon Marcus

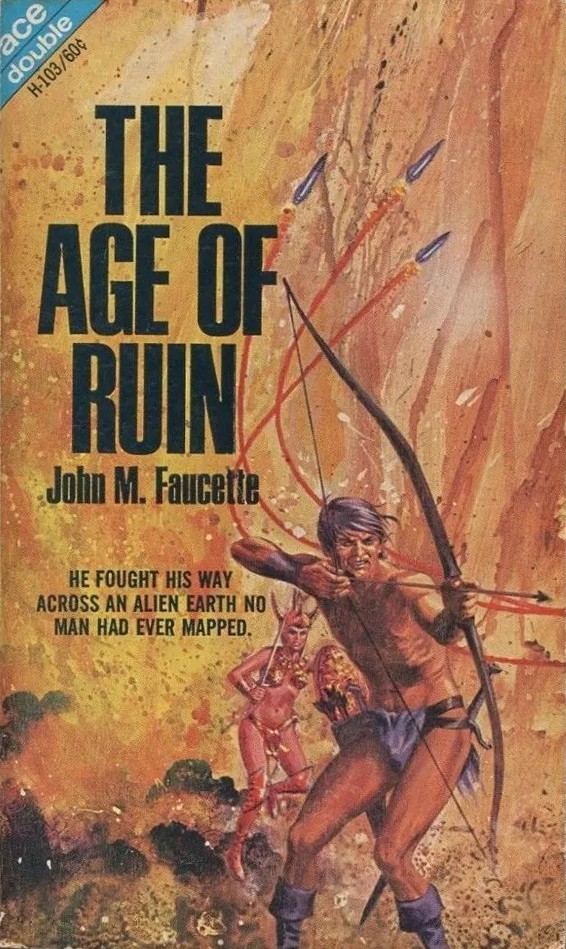

Ace Double H-103

The Age of Ruin, by John M. Faucette

Awakened from his sleep by a nightmare, Jahalazar of the purple hair yet hears the cry of his kind:

Help us, Jahalazar, your people are dying.

So, Jahalazar, a warrior without peer, armed with Chernak, the Throwing Sword, and Lil Chernak, the Slitting Knife, he bids farewell to his adoptive home. The crude realm of Clan Chevy in the bowl of Bomb Valley is like a paradise compared to the the lands Jahalazar must travel—first to Sea City, where the fish-headed people fight off the rubber-suited Zharks and their fearsome weapons that project flesh-devouring Diss. Thence over mountains. Further over higher mountains on the back of friendly, giant spiders. Across the endless plains on which two mechanized armies are locked in eternal conflict.

And on and on, past volcanic and mutated horrors, into domains ruled by sadists, to others dominated by distorted but good souls, and always with the ever-evolving Diss, now sentient and bent on world conquest, nipping at his heels.

Ever in the background: what caused the Age of Ruin, and can humanity rebound from it?

Sounds pretty cool, doesn't it? This is yet another "after the apocalypse" novels, of which Spawn of the Death machine and Omha Abides are fine examples from just this year. Unfortunately, The Age of Ruin is not up to their caliber.

Oh, the writing's not bad, in a sort of derivative, pulpy style. The monsters, scenery, and scenes are pretty interesting. The problem is there's nothing holding them all together. Each chapter is a self-contained story, and ultimately, Jahalazar is a sort of sight-seer. It's almost like Danté's Inferno.

The other issue is that Faucette, the author, throws out all of these monstrosities and weird human nations without any thought of logistics. Here we have the equivalent of Harry Harrison's Deathworld in terms of lethal environment, yet somehow humans are growing food and supporting realms. Given that Jahalazar rarely has the opportunity to sleep, I'm not sure how people manage to do the mundane things that running a civilization requires.

This is Faucette's second book, his first being another Ace Double half, Crown of Infinity, released earlier this year. I haven't read that one so I can't compare, but now I'm mildly tempted.

Three stars.

If you wanted to see more of Helen, the 26-year old acrobatic agent who goes undercover as an 8-year old (first seen in" Fiesta Brava"), then this is your chance. Code Duello is the latest in Mack Reynolds' saga of the United Planets, a future setting in which humanity has spread to the stars, and each planet has the freedom to pursue whichever socioeconomic path it chooses. Usually, it's something modeled on Earth history, and it's often pretty extreme. Mostly, it's a chance for Reynolds to show off his knowledge of history and politics and take real-life societies to absurd extremes.

It's also an opportunity for spy high jinks. There is a race of aliens who inhabit the "Dawnworlds". They don't communicate with humans, but they possess far more power than humanity, and they have been known to destroy perceived competitors if they get too threatening. This is why Earth has set up Section G, a supersecret spy organization whose job is to subtly ensure that all of the planets, despite ostensibly being free from interference, are never allowed to backslide technologically or productively. The idea is that, if we are to have a chance against the Dawnworlders, we must always be progressing rather than sitting on our laurels.

The planet of the week is Firenze, a world based on Florence (of course). Its salient features are that everyone likes to resolve conflicts by dueling (and everyone is quick to want to duel) and the supposedly democratic world is actually a rigidly controlled dictatorship. There is supposedly an "Engelist" underground, always on the verge of taking over, yet no one, not even the government officials, know who the Engelists are, what they stand for, or if any have even been seen in the wild.

The agents who have been sent to Firenze to investigate the situation (actually, explicitly to help the current government against the rebels…which seems like jumping the gun since obviously little was known about the Florentine government or its supposed insurgency) are as follows: Helen, as mentioned above; Dorn, a brilliant algae biologist who also happens to be the strongest man in the galaxy; Zorro, who is a demon with a whip; and Jerry, whose signature feature is his unbeatable luck. Once again, we have the setup for a Retief-style zany adventure, and it is mildly amusing…for a little while. Additional mystery is added when Zorro finds that the Florentines seem to have knowledge of the Dawnworlds, which was supposed to be a carefully controlled United Planets state secret.

But eventually, I got tired of Helen snorting/sneering/smirking through every line, the historical screeds that would flow incongruously from the mouths of various characters (always with relevance to, say, someone who had traveled the world circa 1960), and the slapstick nature of the book. I finished, because I wanted to know how the mysteries ended, but it was definitely a story written on autopilot.

Two and a half stars.

by Victoria Silverwolf

Young and Old

Two new novels deal with the elderly and the young. Other than that, they could not be more different.

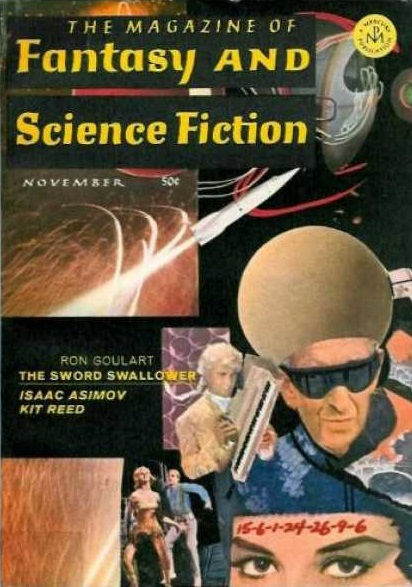

The Sword Swallower, by Ron Goulart

The first novel from this comic writer is a greatly expanded version of a story that appeared in the November 1967 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

Cover art by Gray Morrow.

The Noble Editor didn't care for the novelette when it first appeared. Will the long version be any better or worse?

Cover art by Seymour Chwast.

Ben Jolson is an interplanetary secret agent. As a member of the Chameleon Corps, he has the ability to change his appearance at will. He can look like anybody or anything. He's had a couple of other misadventures prior to this one.

Military officers have vanished. It seems that so-called pacifists are trying to prevent the Barnum system of planets from conquering Earth. Ben's job is to find out who's responsible and stop them.

(I guess this explains the otherwise obscure title. Making a sword disappear is kind of like making a soldier disappear, I suppose.)

At this point, I expected a satire of militarism, given the fact that the bad guys are pacifists and the good guys are attacking Earth with deadly force. It didn't quite work out that way.

Ben disguises himself as a very old man and sets out for a rejuvenation center on a planet that also serves as a gigantic cemetery. He gets mixed up with a female secret agent who is on his side, but who isn't part of the Chameleon Corps.

Following the clue he finds there, he changes into a young person and infiltrates a group of beatnik/hippie/folk singer types. From there, he goes to the huge cemetery to confront the guy behind the disappearances. Along the way he has to rescue the female agent.

That's the plot of the novelette, as well as the beginning and end of the novel. What's been added to increase the word length is Ben's involvement with a computer that acts as a crime boss. There's some other stuff, too.

The book didn't amuse me. If you think it's funny that Ben beats the computer at Monopoly, you may get a kick out of it.

It doesn't work as action/adventure/suspense, because Ben immediately gets out of trouble every time the bad guys get the upper hand, either by changing his shape or just by using his fists.

It fails as satire for a couple of reasons. The supposed pacifists turn out to be intent on arming Earth against the invaders. That undermines any Orwellian War is Peace theme. The portraits of the elderly and the young are just silly rather than biting.

The best I can say about the novel is that it's a very fast, easy read. The breakneck pace is similar to one of Keith Laumer's yarns.

Two stars.

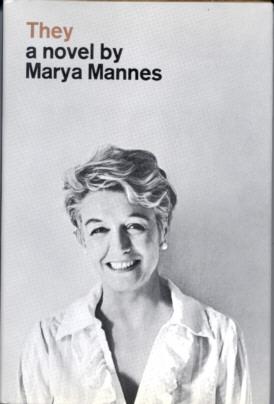

As far as I can tell, the only other work of fiction by this author is a novel that came out twenty years ago. (There may be some short stories of which I am not aware.) She's much better known for nonfiction, and has a reputation for being an acerbic social critic.

Cover art by Robert Hallock.

Her first novel was a ghost story, in which a dead woman looks back on her life. Maybe she'll publish another one in 1988. For now, we've got a dark vision of the near future.

Photograph of the author by Alex Gotfryd.

The fact that the cover depicts the author is our first hint that this isn't a typical science fiction novel. That seems more appropriate for a book of essays or some such. Her warm smile doesn't fit with the mood of the book either.

Not many years from now, people who are fifty years old are forced to retire and live in segregated communities, cut off from contact of any kind with younger folks. At the age of sixty, they have to pass a physical exam or else be forced to choose between suicide or execution by the government. At sixty-five, not even a clean bill of health can save them from mandatory death.

(Shades of Wild in the Streets, with its concentration camps for people over thirty-five years of age! Despite similar themes, that movie and this novel are quite different experiences.)

The narrator is one of five people living in a house by the sea. (As a special privilege, the government allows these creative types to dwell there instead of the usual ghetto for old folks. The house used to belong to the narrator and her husband, who killed himself when the youth movement seized power.)

Besides the narrator, who was a journalist, we have a painter, his model, a composer of classical music, and a writer of popular songs. The latter is also the narrator's current lover. The composer had a much younger wife who lived with the others for a while, but soon left to be with folks in her own age group.

I should also mention the narrator's dog, the composer's cat, and the bird that belongs to the painter and the model, because they are important characters as well.

Besides providing the reader with exposition, the narrator records the philosophical discussions and arguments among the five, often quoting them at length.

(The author does a fine job of making their voices distinct. The painter is angry and bitter, his speech full of profanity. The model speaks simply and emotionally. The composer is elegant and intellectual. The songwriter is witty and satiric.)

As you might be able to tell, much of the book consists of talk. The characters discuss what went wrong with society, and how it might be cured. Don't expect a lot of action.

An odd plot twist occurs late in the book. A beautiful, dark-skinned young man shows up, apparently washed up by the ocean. He doesn't speak, and his origin remains a mystery. The novel ends with a group decision by the five elders.

Besides dealing with the youth movement and attacking the way it disregards the past, the book also raises a lot of other issues. Art, music, politics, and education are discussed at length.

In addition to this rather dry material, there's some beautiful writing about the seashore, which the author obviously loves.

Not for all tastes, to be sure! I suspect a lot of readers will be bored to tears by all the talk, and find the unexplained arrival of the young man baffling.

Two stars.

by Cora Buhlert

A King on the Run: The Goblin Tower by L. Sprague De Camp

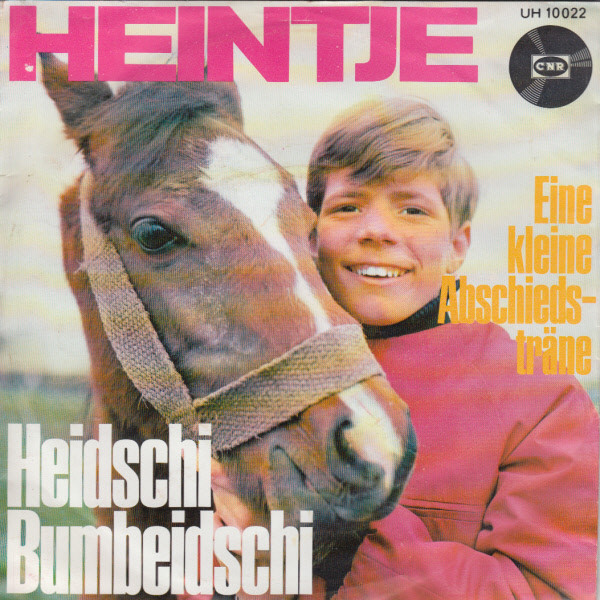

Do you remember thirteen-year-old Dutch singer Hein Simons a.k.a. Heintje, who is not only the breakout star of 1968 in West Germany, but whose sappy song "Mama" is the most successful single of the year?

Young Heintje followed up the success of "Mama" with a Christmas album entitled Weihnachten mit Heintje (Christmas with Heintje) where he sings traditional German Christmas carols. He also has a new single out called "Heidschi Bumbeidschi", which is even more painfully saccharine than "Mama", if that's possible. It is not a Christmas song, but a traditional Bohemian lullaby, which unfortunately does not stop West German radio stations from playing "Heidschi Bumbeidschi" in continuous rotation in the run-up to the holidays.

Hein Simons is clearly a very talented young man. I just hope that he eventually gets to sing songs that are more appropriate to a modern teenager.

Off With His Head

During the latest visit to my trusty import bookstore, I spotted a familiar name in the paperback spinner rack, namely L. Sprague De Camp, who has been editing and tinkering with the Conan reprints for Lancer Books. However, this time around, it wasn't another Conan book, but an original fantasy novel by L. Sprague De Camp called The Goblin Tower. The striking cover by J. Jones, probably the most talented new artist to emerge in recent times, drew me in and the blurb on the back sounded intriguing as well, so I picked the book up as a St. Nicholas Day present to myself. So let's see how L. Sprague De Camp does when he is not messing with Conan…

After a dedication to De Camp's fellow swashbuckler Lin Carter and a map of Novaria, the setting of the tale, The Goblin Tower certainly starts off with a bang or rather a chop, since Jorian, the current king of the city of Xylar, is about to be executed in front of the city gates. For in Xylar, it is custom to publicly behead the king every five years. Whoever catches the severed head shall become the new king, until it is his turn to mount the scaffold.

As methods of selecting a government go, this one is rather bloody and not particularly efficient, though it does prevent the establishment of tyranny, because every ruler comes with a built-in expiration date, as well as bloody wars of succession. Also kudos to L. Sprague De Camp for remembering that a monarchy is not necessarily hereditary; for example the Holy Roman Empire initially was not.

Jorian seems resigned to his fate and sanguine enough, even though he never desired to be king in the first place. Nor has he any intention to lose his head and so Jorian tricks the executioner and assembled populace of Xylar and escapes his own beheading with the aid of the wizard Karadur and his magical rope trick, which allows Jorian to climb away from the scaffold into what his people view as the afterlife.

This Never Happened to Conan

The "afterlife" in which Jorian briefly finds himself turns out to be our modern world. Worse, poor Jorian materialises in the grassy median strip of a highway and almost gets run over by a car – not that Jorian knows what a car is; he initially thinks it's a monster before realising that it is a vehicle. Jorian also meets a police officer in his brief sojourn in the modern world, though he mistakes the man for a carpenter, since Jorian has never seen a gun before, but finds that it looks like a carpenter's tool.

L. Sprague De Camp is a more humorous and satirical writer than Robert E. Howard was (though Howard could be very funny as well, e.g. in his Sailor Steve Costigan stories), which means that their styles don't always mesh well in the posthumous Conan collaborations. However, the brief interlude of our modern world seen through the eyes of a Barbarian king from a fantasy world plays to De Camp's strengths. The scene is hilarious, though De Camp can't resist adding some of his own opinions about the shortcomings of our world. It's also impossible to imagine anything like this ever happening to Conan.

A Quest and a Roadtrip

Alas, Jorian's sojourn in the modern world is short-lived, before he returns to his own world to meet up with Karadur. He also learns that the wizard didn't just save Jorian's life out of the goodness of his heart. No, there is a price. Karadur wants Jorian to help him retrieve a chest full of magical manuscripts called the Kist of Arvlen and bring it to a conclave of wizards at the titular Goblin Tower.

So Jorian and Karadur set off on their quest and now we learn the reason for the map at the beginning of the book, 'cause the pair will visit every single location marked thereon, have adventures and get entangled with beautiful women, vile wizards, and treacherous nobles, all the while pursued by Xylarian soldiers who want to recapture their errant king for his beheading. Along the way, Jorian rescues twelve slave girls from a brotherhood of retired executioners, once he realises that the executioners want to use them for practice to keep their skills sharp, and steals the Kist of Arvlen from the bedchamber of a shape-shifting serpent princess. He narrowly escapes being sacrificed to a jungle god and takes part in a heist to steal the statue of a frog god, replacing it with a real frog, much to the confusion of the worshippers.

Finally, Jorian and Karadur and the Kist of Arvlen make it to the conclave of wizards at the Goblin Tower, which turns out to be an edifice constructed from real goblins, who have been turned to stone by magic. What could possibly go wrong with holding a wizard symposium in such a place?

A Meandering Tale

Jorian and Karadur's adventures are a lot of fun, but they are also meandering and episodic to the point that every chapter seems more like a standalone short story than part of a greater whole. The fact that Jorian, who is more Sheherazade than Conan, frequently regales the people he meets by telling stories reinforces that episodic and picaresque feel of the novel.

However, this fault is not unique to The Goblin Tower, but appears to be a structural issue with the entire genre that Fritz Leiber dubbed "sword and sorcery". Born in the pages of Weird Tales almost forty years ago, sword and sorcery is a genre of short, fast adventures. Whether it's Robert E. Howard's tales of Conan the Cimmerian or Kull of Atlantis, Fritz Leiber's stories about Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser or the dreamlike adventures of C.L. Moore's Jirel of Joiry, all of these characters initially appeared in short stories and novellas, and modern heroes in the same mode such as Michael Moorcock's Elric of Melniboné, Roger Zelazny's Dilvish the Damned or John Jakes' Brak the Barbarian follow suit.

However, the genre landscape has changed since the heyday of the pulps and the dominant form – particularly for fantasy – is now the novel. Of course, there are sword and sorcery novels, from Robert E. Howard's The Hour of the Dragon a.k.a. Conan the Conqueror via Poul Anderson's The Broken Sword, Björn Nyberg's The Return of Conan a.k.a. Conan the Avenger, Michael Moorcock's Stormbringer and Lin Carter's A Wizard of Lemuria all the way to Fritz Leiber's Swords of Lankhmar, Joanna Russ' Picnic on Paradise and De Camp and Carter's Conan of the Isles. Having read and enjoyed several of these novels, it's notable that many of them tend to be very episodic and feel like fix-ups, even if they aren't. This makes sense in the case of The Hour of the Dragon, which was after all serialised in Weird Tales, or Swords of Lankhmar, the first part of which appeared as a standalone novella in Fantastic. But The Goblin Tower is a paperback original that was never serialised anywhere, so why is it structured like a serial?

Nonetheless, The Goblin Tower is a highly enjoyable novel, which allows De Camp to show off his humorous side, something he rarely has the opportunity to do with the Conan stories. Furthermore, the open ending is very much begging for a sequel and I for one will certainly pick it up.

Four stars

![[December 16, 1968] Adventure and eulogies (December Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/681216scope-672x372.jpg)