Del Shannon's on the radio, but I've got Benny Goodman on my hi-fi. Say…that's a catchy lyric! Well, here we are at the end of April, and that means I finally get to eat dessert. That is, I finally get to crack into The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. While it is not the best selling science fiction digest (that honor goes to Analog by a wide margin), it is my favorite, and it has won the Best Magazine Hugo three years running.

So what kind of treat was the May 1961 F&SF? Let's find out!

Carol Emshwiller returns with the lead story of the issue, the sublime Adapted. It can be hard to resist the incessant mold of conformity, even when blending in means losing oneself. Emshwiller's protagonist loses the battle, but, perhaps, not all hope. Four stars.

The somber Avram Davidson teams up with unknown Sidney Klein (perhaps the idea man?) with The Teeth of Despair. It's a cute but forgettable story involving a cabal of underpaid professors, a loser with a metal dental plate, a quiz show, and something that isn't quite telepathy. Ever wonder how Van Doren did it? Three stars.

All the Tea in China is offered up by Reginald Bretnor, the real name behind the Ferdinand Feghoot puns (q.v.). Watch as despicable Jonas Hackett, a mean cuss who wouldn't commit a kind act for the entirety of the Orient's signature beverage, is given what for by Old Nick. Nicely told. Three stars.

Somebody to Play With, by Jay Williams, is a compelling story with a brutal sting in the tail. It may make sense for the adults of a tiny colony on an alien world to be overly cautious, but does the desire for security warrant genocide? Telling from a child's point of view, Williams skillfully conveys the claustrophobia of the outpost, the wonder of the strange world, the thrill of making an extraterrestrial friend, and the heartbreak of betrayal by one's closest kin. Four stars.

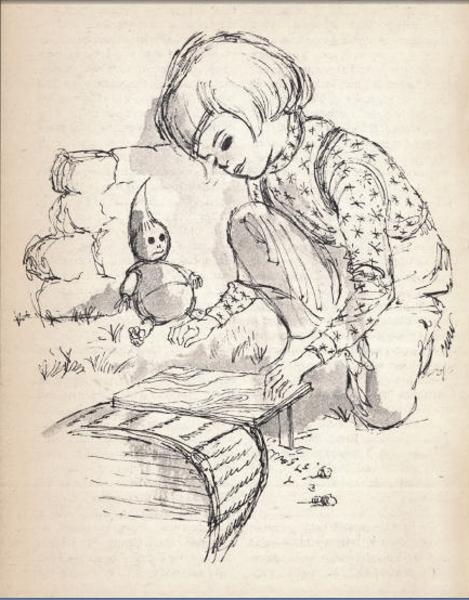

I know nothing about C.D. Heriot save that I imagine he is British. He writes Poltergeist in an affected manner that almost, but not quite, dulls the impact of this story of a neglected pre-adolescent who conjures up her own malicious playmate. In the hands of Davidson, it'd rate four or five stars; in this case, just three.

Stephen Barr's Mr. Medley's Time Pill is By His Bootstraps all over again, and it commits the same sin: telling both sides of a time loop story. We already know what will happen after reading the first half; what is the point of conveying it twice? Two stars.

The Country Boy is the latest in G.C.Edmondson's Mexican-themed tales, a direct sequel to Misfit. As is often the case with Edmondson, the story is clever, but the banter isn't, though he tries. Too hard, really. Three stars.

Heaven on Earth is The Good Doctor Asimov's science contribution for this issue, on the measurement of the celestial sphere and its resident stars. It's all about degrees, base-60 number systems, and an Earth-sized planetarium. I love his mathematical articles; I feel he often does his best work with what could be the most sterile of subjects. Four stars.

The Flower is 11-year old Mildred Possert's submission. Editor Mills thinks she shows promise, and I don't disagree.

Henry Slesar gives us The Self-improvement of Salvatore Ross, involving a fellow who can bargain for anything – including physical traits. He swaps a broken leg for pneumonia, his hair for cash, and so on. The twist ending is a bit out of nowhere, but it's a good story nonetheless, the sort of thing that might get adapted for The Twilight Zone. Three stars.

The appropriately named Final Muster is, indeed, the last story in the book (and the inspiration for the issue's cover). I believe this is Rick Rubin's first effort, and he hits a triple right out of the box. The premise: by next century, war is such a specialized, abhorred profession that soldiers are frozen in stasis and thawed only when needed. This is a volunteer corps whose ranks are filled with combatants who cannot find joy in peaceful civilian life. But what happens when war ends entirely? A thoughtful story whose only fault is that it perhaps doesn't go quite far enough in its projections. Four stars.

With dessert finished, we can now run the numbers. This issue came out at 3.3, edging out this month's Analog (3), and IF (2.75). Analog had the best story of the month (Death and the Senator). There was one (count them) woman writer out of 21 stories, an abysmal score.

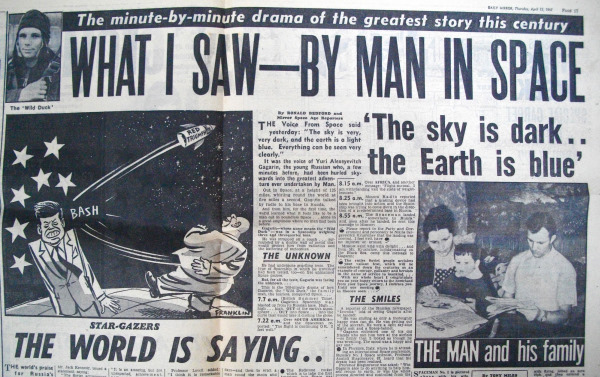

A lot of space news coming up soon what with Alan Shepard, Gus Grissom, or John Glenn scheduled to be the first American in space on May 4th. Stay tuned!