by Gideon Marcus

The measure of a story's quality, good or bad, is how well it sticks in your memory. The sublime and the stinkers are told and retold, the mediocre just fades away. If you ever wonder how I rate the science fiction I read, memorability is a big component.

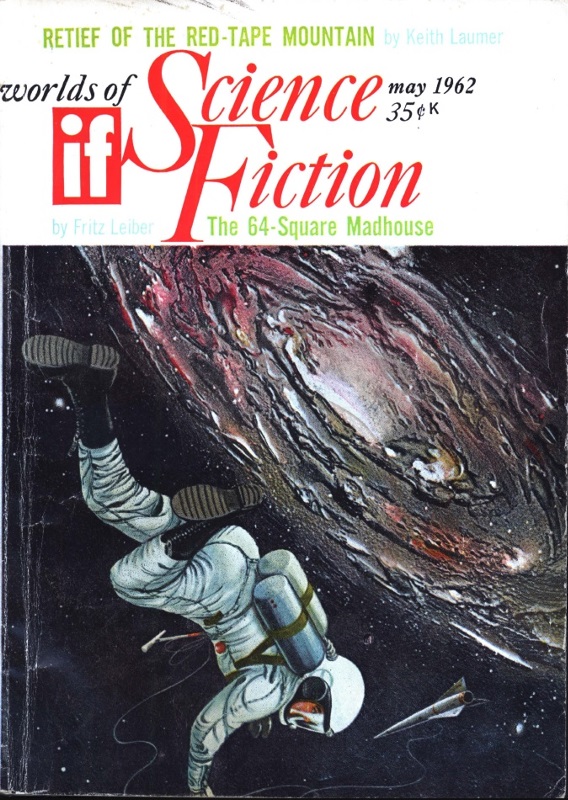

This month's IF has some real winners, and even the three-star stories have something to recommend them. For the first time, I see a glimpse of the greatness that almost was under Damon Knight's tenure back in 1959. Read on, and perhaps you'll agree.

Retief of the Red-Tape Mountain, by Keith Laumer

Laumer continues to improve in his tales of the omni-capable diplomat hamstrung by the flounderings of a sub-capable bureaucracy. In this story, Retief is dispatched to make peace between the settlers of a new colony, and a band of aliens that has recently popped onto the scene. Comedy is hard to write, and it's harder (but more rewarding) to anchor humor to a serious backbone. There are some genuinely funny moments in Mountain, and it's also a good story. Four stars.

The Spy, by Theodore L. Thomas

An extraterrestrial (but human) reincarnation of Nathan Hale is captured by musket-bearing folk and tried for espionage. I enjoyed it well-enough at the time, but the ending sat poorly. There's just not enough to this piece. Two stars.

Death and Taxes, by H. A. Hartzell

I really enjoyed this fanciful tale of a beneficent sea-captain's ghost, the impoverished artist he comes to haunt (or perhaps, "with whom he cohabitates" is more appropriate, and the lady who is the object of the artist's affections. It's Lafferty-esque, a little bit disjointed but a lot of fun. I've never heard of Hartzell before, so s/he is either a promising novice or a slumming veteran. Four stars.

by DYAS

Misrule, by Robert Scott

Politics is a chaotic game. Strikes, protests, riots – these can really throw a wrench into the workings of government. What if you could do away with all that? Subvert all the anti-government feelings into one quadrennial orgy of rapine and destruction, a blowing off a steam that keeps things quiet for another four years? Scott's tale isn't particularly plausible, but it is vivid. Three stars.

Deadly Game, by Edward Wellen

This is a weird Isle of Dr. Moreau-type tale about a park ranger who engineers his charges to be vicious guerrillas, making the animals sentient masters of their own fate. Another well-told story that doesn't make a lot of sense. Three stars.

The Hoplite, by Richard Sheridan

In the far future, flesh is not enough to withstand the rigors of war. One solution is to surround the warriors in an exo-skeleton of metal, the other…well, you'll have to read to find out what can resist a steel humanoid goliath. Evocative but somehow hollow. Three stars.

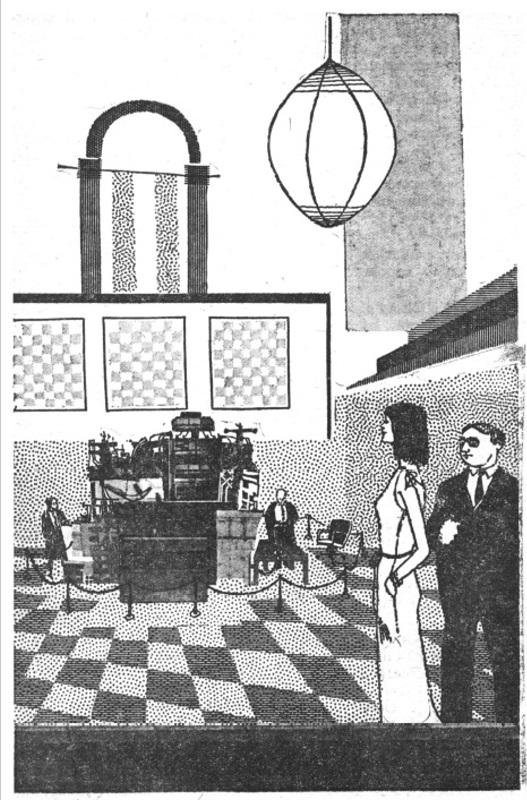

The 64-Square Madhouse, by Fritz Leiber

Some science fiction stories are so imaginative yet so plausible that you can be convinced that you are seeing the future. Leiber's tale depicts a chess tournament that takes place on the eve of the time when computers become good enough at the game to beat the best Grandmasters. This is not some staid Robot vs. Man tale, but a cunning extrapolation of the current state of the art in cybernetic chess to a few decades into the future. Add to it a cast of well-drawn characters and a multi-peak story arc, and you've got a story that will likely be referenced by name the day fiction becomes reality. Five stars, and bravo.

by BURNS

Gramp, by Charles. V. DeVet

The gift of telepathy is a double-edged sword, as one boy soon discovers. DeVet does a good job of capturing a youth's voice, and he's no stranger to sensitive stories. Would make a decent The Twilight Zone episode, perhaps. Three stars.

The Other IF, by Theodore Sturgeon

Ted Sturgeon's non-fiction piece is about an IF magazine that never was. Apparently, Sturgeon has wanted to have his own magazine since the War Years. The digest he conceived, which he planned to call IF, would have exclusively published "If this goes on" stories: short-term predictions turned into plausible stories. He concludes his non-fiction account of the IF that never was with a few guesses of his own – since he wrote the article in December, their accuracy is already a matter of record. He then invites you, the reader, to make your own and send them in.

Do you have any hunches on what's in store for this Summer?

(Three stars)

The Expendables, by Jim Harmon

Harmon can always be counted on to provide readable fiction. In this case, we have a droll story about the man who invents the perfect garbage disposal…but can the Laws of Thermodynamics be so easily beaten? Or the Mafia? The FBI? My favorite line, "My opinion as to the type of person who followed the pages of science-fiction magazines with fluttering lips and tracing finger were upheld." Three stars.

***

Added up, that puts us at 3.4 for the month, a respectable score for what used to be one of the lesser mags, and it was worth it just for the Leiber. A host of interesting, implausible stories, and one humdinger of a plausible one. I guess I'll just have to renew my subscription to this promising digest. Good on you, Editor Fred Pohl!