by Gideon Marcus

The Thrill of Combat

It was just twenty years ago that the second war to end all wars drew to an explosive close. Two titans of tyranny (and their little brother) were defeated by the Arsenal of Democracy. Clearly, World War 2 was "the good war:" there's a reason it is now as popular on television and in wargames as the Western and the Civil War.

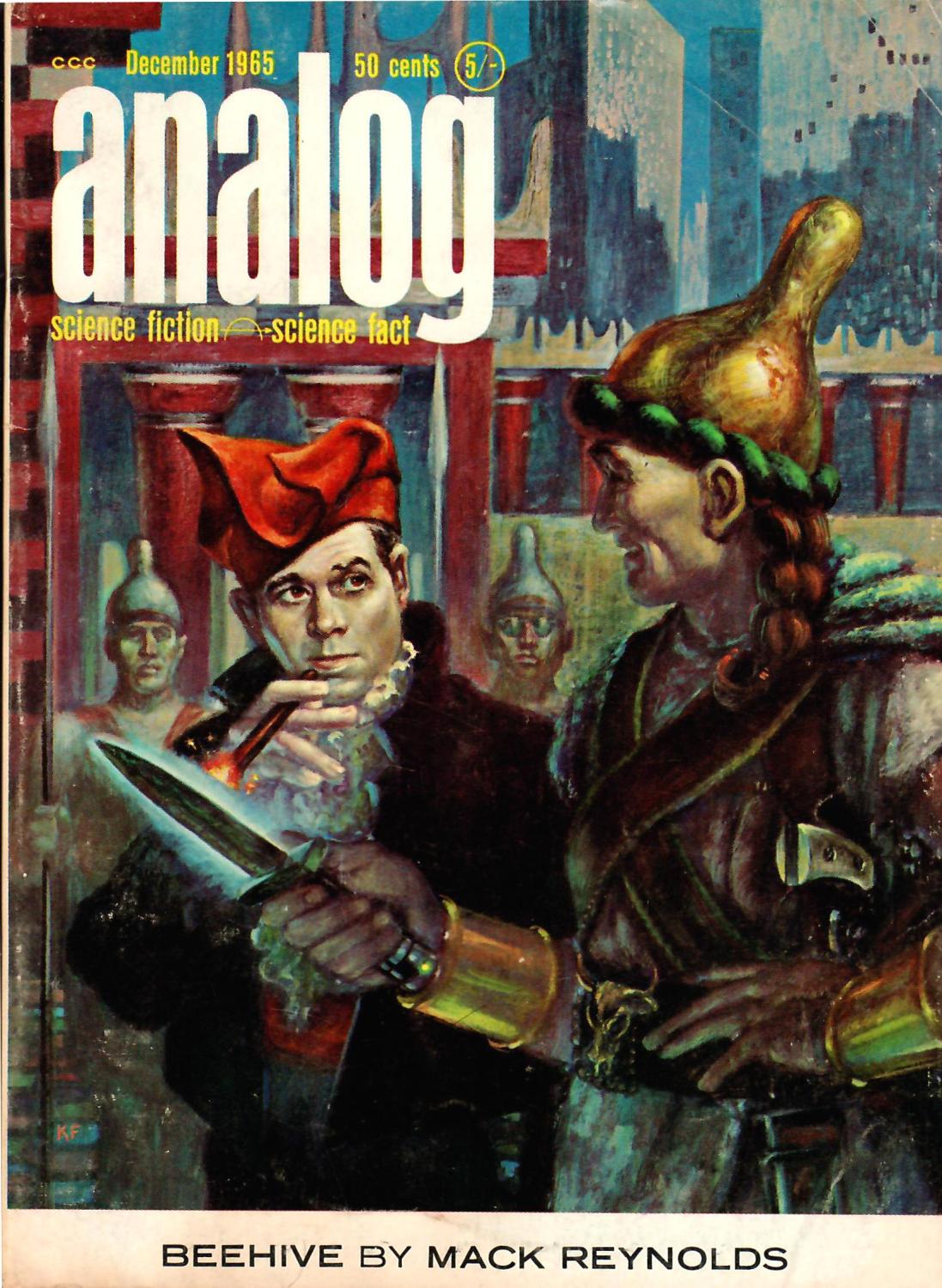

And just in time. After the sloggish stalemate of Korea and the painful "escalatio" in Vietnam (credit to Tom Lehrer), war needs to be fun again. I suppose it's no surprise that war is not only a common theme in science fiction, but the good and fun kind of war is the thread that ties together the December 1965 issue of Analog, notoriously the most conservative (reactionary?) of the outlets in our visionary genre.

One War after Another

by Kelly Freas

Beehive (Part 1 of 2), by Mack Reynolds

Ronny Bronston, forgettably faced but utterly competent agent for Earth's "Section G" is back. Last we saw him, he'd been on the trail of interstellar troublemaker, Tommy Paine, spurring revolution on dozens of worlds. Turned out that Paine was actually Section G, itself, skirting the non-interference clauses of the galactic charter to ensure that the colony worlds didn't stagnate.

In Beehive, we find out why: a century ago, the first sentient alien was found. Well, actually, its corpse — it had been a casualty of a war of extermination. And we still don't know who their enemy was, or if they'll soon be knocking on our doors. That's why the super secret service has been surreptitiously trying to speed of progress on all of the colony worlds so that when the aliens do come, we'll be as ready as possible.

One of the more successful colonies, the putatively libertarian but actually authoritarian world of Phrygia appears to be making a play to turn the galactic society into an Empire, and Bronston is dispatched to get the facts on the ground. But when he gets there, the agent discovers that the wheels have wheels within them, and the Phrygian dictator knows far more about the alien threat than Section G.

by Kelly Freas

While this serial has a definite hook of a cliffhanger, for the most part, it's not Reynolds' best…or even his middlin'. There's a glib, breezy quality to it that is both smug and serves to reduce the tension. The central idea is repugnant, too — that Earth knows best, and their underhanded means of stimulating progress are justified. But then Campbell probably didn't watch that recent documentary on how the CIA messed up in Guatemala.

Anyway, I'll keep reading, but it's two stars right now.

Warrior, by Gordon R. Dickson

by Kelly Freas

Another sequel and another war. In Dickson's Dorsai universe, humanity has spread to thirteen worlds, each focusing on an aspect of cultural development. The Dorsai have made war their profession, turning it into a sublime art, and they are the most esteemed and feared mercenaries.

In the novella/novel, Soldier, Ask Not, we were introduced to twin brother generals, Kenzie and Ian Graeme. The former is a charismatic leader, the latter a sullen but matchless strategician.

Ian Graeme returns in Warrior, traveling to Earth to seek justice for 32 of his men, slaughtered when their glory-hunting captain disobeyed orders to lead a hopeless charge. The officer was court martialed and executed, but Graeme knows that the real culprit is his gangster brother. Warrior tells the tale of Graeme and the brother's eventual and climactic confrontation.

There are a lot of inches in this story devoted to the obvious prowess of Mr. Graeme, his dark eminence, his barely suppressed strength, his intimidating military demeanor that requires no uniform, etc. etc. Frankly, it all runs thin early on.

Still, it's a pretty good story (breathlessly recommended by my nephew David…but then so was Beehive), and the display of Dorsai tactics, trapping the brother within the trap being laid for Graeme, was effective.

Three stars.

Heavy Elements , by Edward C. Walterscheid

Ever wonder how the transuranium elements were fashioned? Walterschied returns for a very comprehensive article on the subject. There's a lot of good information here, and it's reasonably well delivered. It's also very dense (no pun intended), certainly not in the Asimov style. It took me a few sittings to get through.

Three stars.

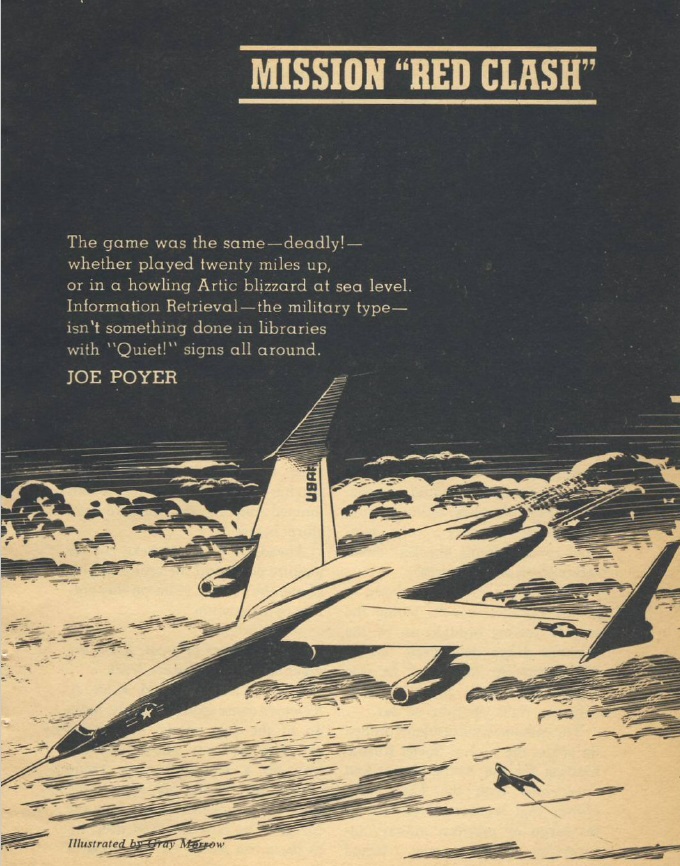

Mission "Red Clash", by Joe Poyer

by Gray Morrow

Joe Poyer's first story is essentially the Analog version of the MacLean novel, Ice Station Zebra. The pilot of a next-generation recon plane, the hypersonic X-17, is forced to bail out over Norway after being shot down by a Russian interceptor. Now he, and the three men dispatched from the nuclear cruiser John F. Kennedy, must evade squads of Soviets and survive frigid conditions to get critical intelligence back to our side.

Told with technophiliac details so lurid that I felt it belonged under rather than on the counter, there's not much of a story here. Mission lacks context, characterization, and conclusion, leaving a competently told middle section of an unfinished novel. It's low budget Martin Caidin.

Two stars.

Countercommandment, by Patrick Meadows

by Domenic Iaia

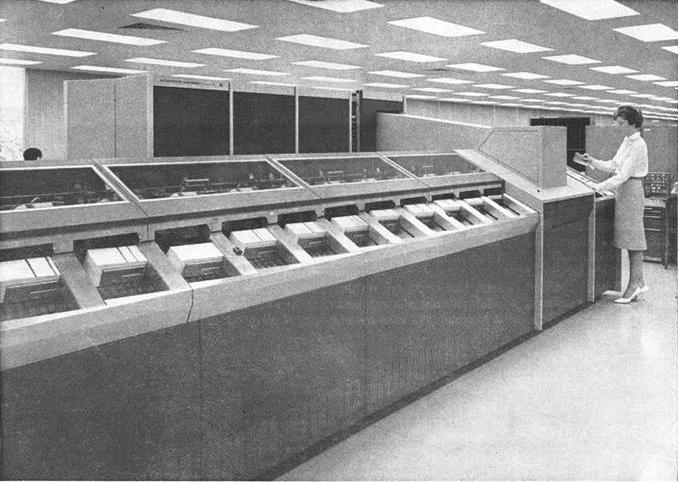

Last up, a computer scientists is rushed to NORAD to find out why, three hours after World War 3 was declared by the Chinese, the Big Brain has not executed a countersrike. And why, despite the efforts of the enemy, their missiles haven't launched either.

This is a two page story padded to ten with the gimmick that the computers, having access to our most sacred documents, which all speak to the sanctity of human life, could not in good conscience end humanity.

It might work in Heinlein's new serial currently running in IF. It makes no sense for computers of 1970s vintage, and it comes off as mawkish.

One star.

One Million Deaths is a Statistic

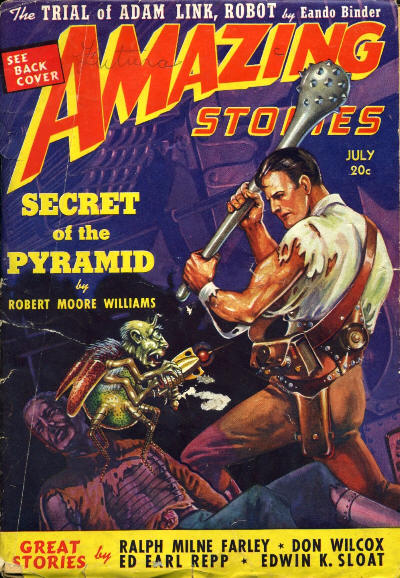

This war-soaked issue of Analog scores a dismal 2.2, barely beating out the truly awful Amazing (1.8).

Above it, we have IF (2.6), New Writings #6 (2.9), Galaxy and New Worlds (3), Science Fantasy (3.1), and the superlative Fantasy and Science Fiction (3.9)

In keeping with the (not entirely accurate) notion that war is a "man's game", there were no entries by women this month. Zero. Goose egg. Color me dismayed.

And on that note, we are done with all of the science fiction magazines with a 1965 cover date. Rest assured, we have compiled all of the statistics from the past year, and our Journey-Vac will be spitting out a fine edition of the '65 Galactic Stars at the end of next month.

You won't want to miss it!

And speaking of stars…

If you caught my review last year of Tom Purdom's I Want the Stars, then you know why I was so excited at the chance to reprint it. And now it can be yours! This new Journey Press edition also comes with a special 'making-of' section.

Get yourself a copy, and maybe one for a friend!

![[November 30, 1965] War is Swell (December 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/651130cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 20, 1965] A fine cup of coffee (December 1965 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/651120cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 16, 1965] Crime and Punishment (January 1966 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n05_1966-01_dtsg0318.Anon_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

![[November 12, 1965] Doldrumming (December 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/amz-1265-cover-481x372.png)

![[November 10, 1965] Strangers in Strange Lands (December 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/651110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 8, 1965] You Must Be Mythtaken (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Myth Makers)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/651108horseofdestruction-672x372.jpg)

![[November 4, 1965] The Best Bad Science Fiction Wrestling Can Offer (A Review of Two Films of <i>El Santo</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/651104movie-472x372.jpg)

Zombies steal children from the orphanage and light it on fire. Because they're evil.

Zombies steal children from the orphanage and light it on fire. Because they're evil.

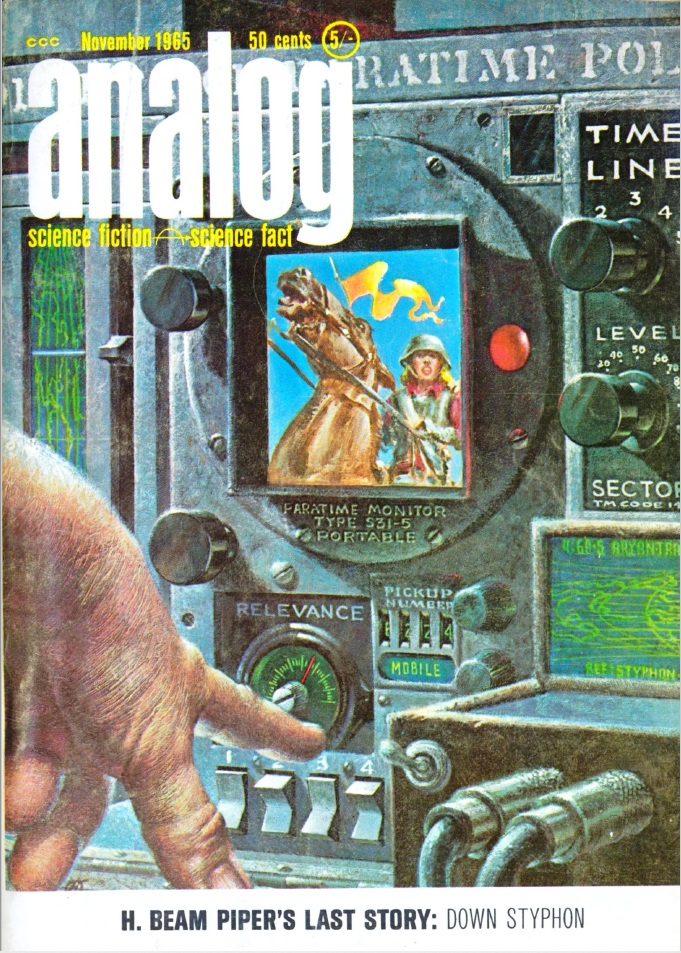

![[October 31, 1965] Finished and Unfinished Business (November 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651031cover-672x372.jpg)

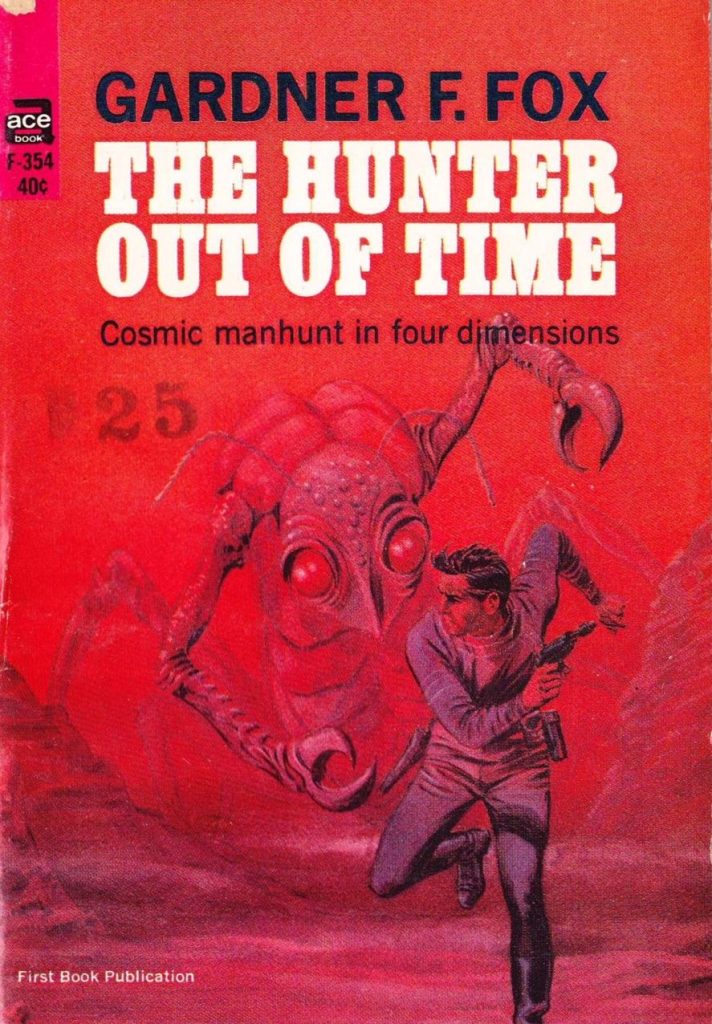

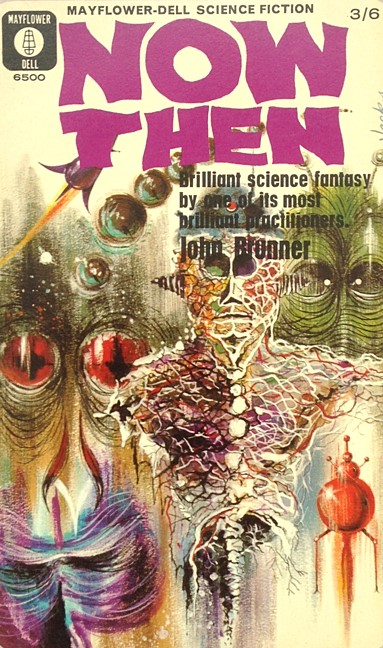

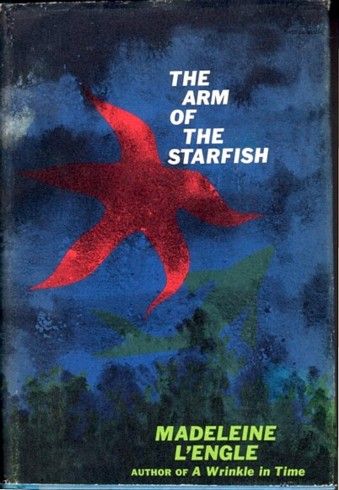

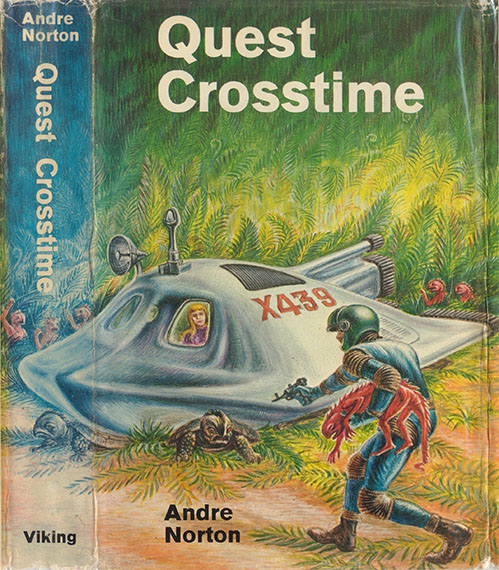

![[October 24, 1965] "What time is it?" (October Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651024covers-1-672x372.jpg)

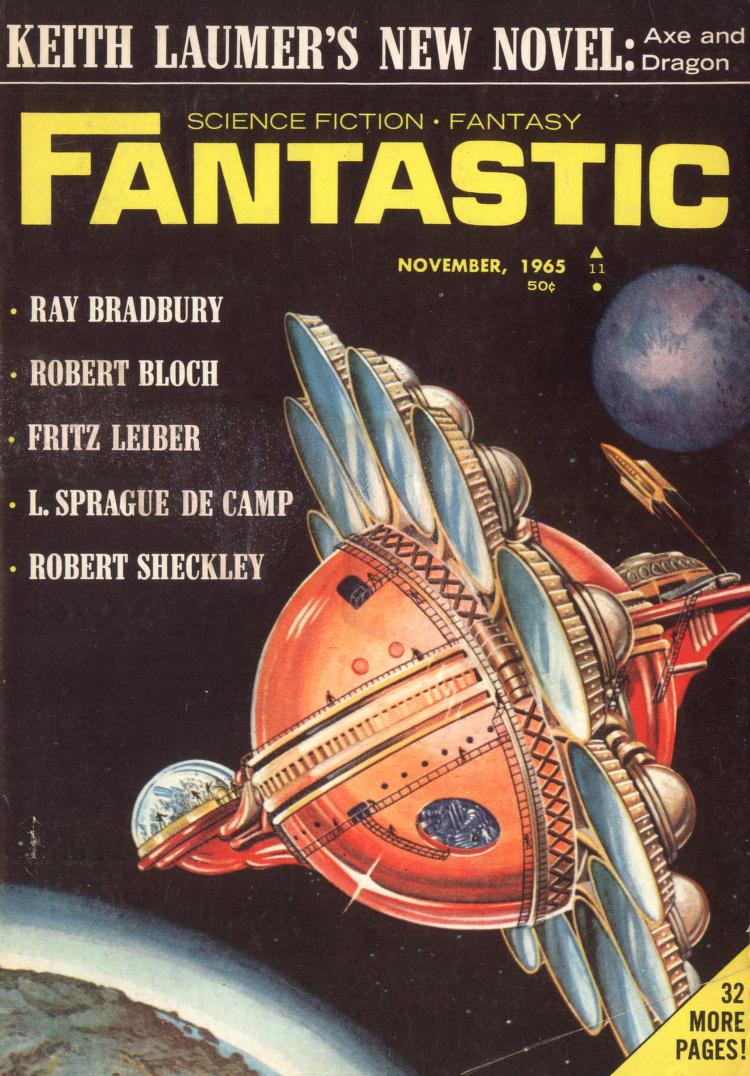

![[October 22, 1965] Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow (November 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Fantastic_v15n02_1965-11_Lenny_Silv3r_0000-2-672x247.jpg)