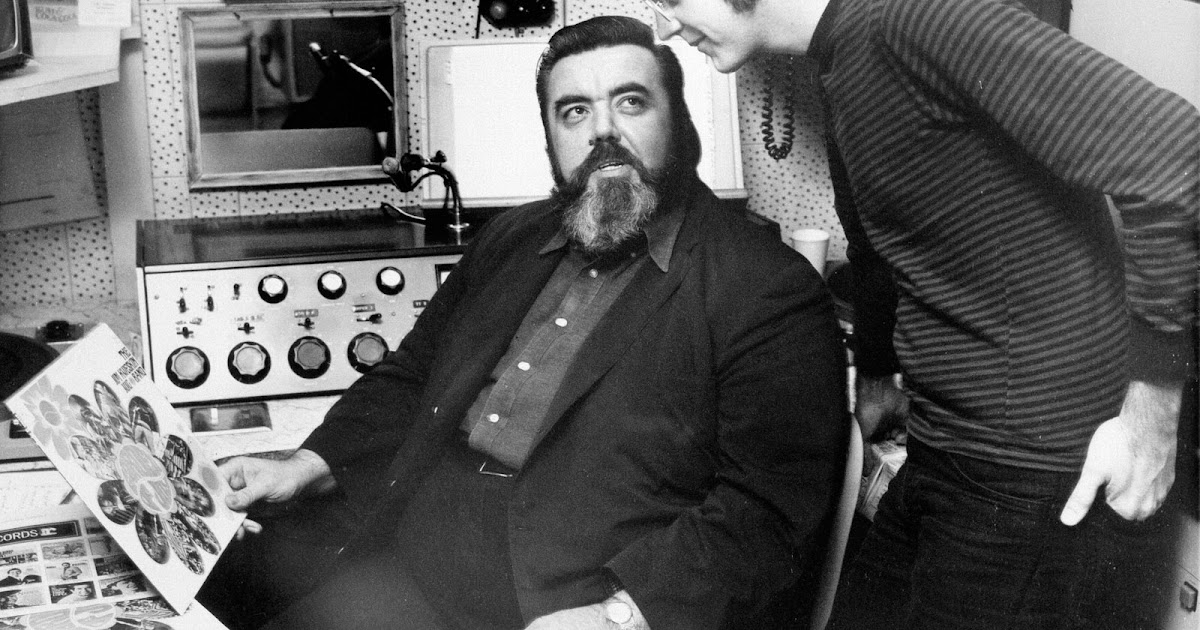

by John Boston

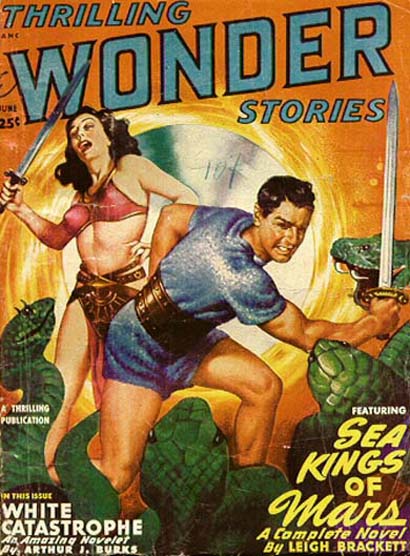

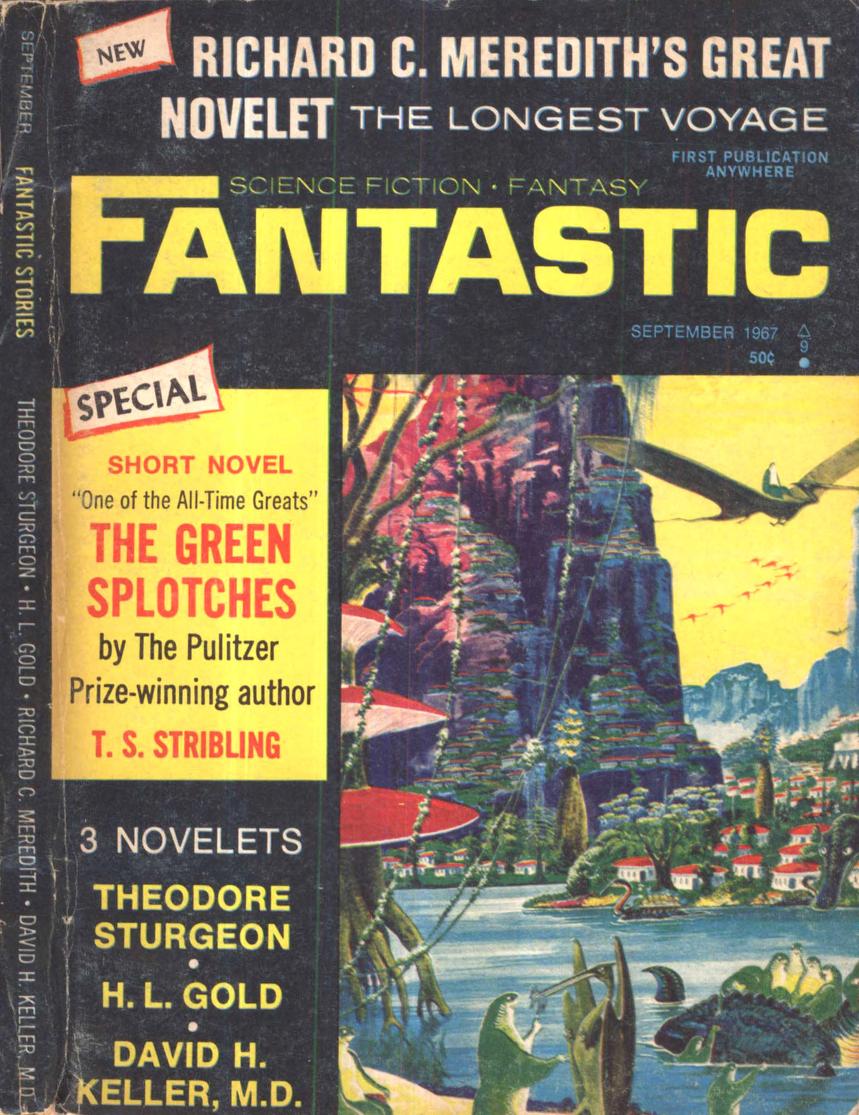

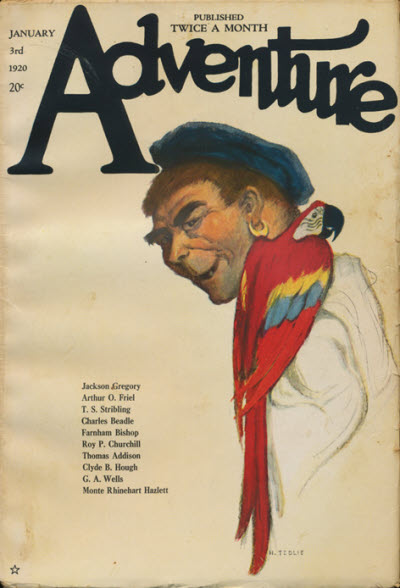

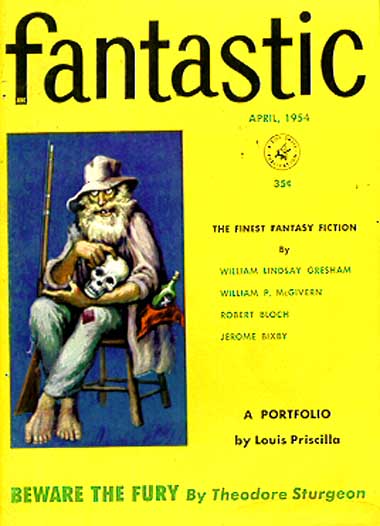

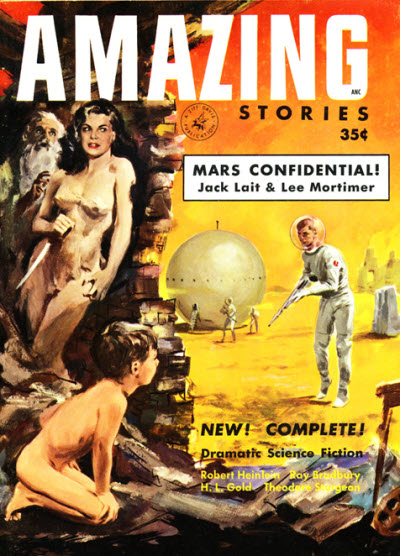

The October Amazing is the second instance of what may prove to be the magazine’s New Look. Like the June issue, it is fronted by a pleasantly garish and nouveau-pulpish cover that, though uncredited, is known to the cognoscenti as another by Johnny Bruck, reprinted from a 1963 issue of the German Perry Rhodan magazine. Farewell Frank R. Paul? We’ll see. And maybe the contents are being updated as well. Of the five reprinted stories here, all are from the late 1940s or the ‘50s, at least in publication date.

by Johnny Bruck

That is not necessarily good news; Amazing published plenty of dreck through most of its history. Selection is all. But this issue’s selection is pretty decent. Also Harry Harrison’s book reviews are still here, with a fillip. In addition to Harrison’s own reviews of a new Edgar Rice Burroughs bio, the latest Analog anthology, and an Arthur Sellings novel, there is Brian Aldiss’s review of Harrison’s own The Technicolor Time Machine—back-slappingly complimentary, as one might expect from these close collaborators. Harrison and Aldiss edited this year’s Nebula Award Stories, due out just about now, and it appears that they will be joining the party with their own “year’s best” anthology next year.

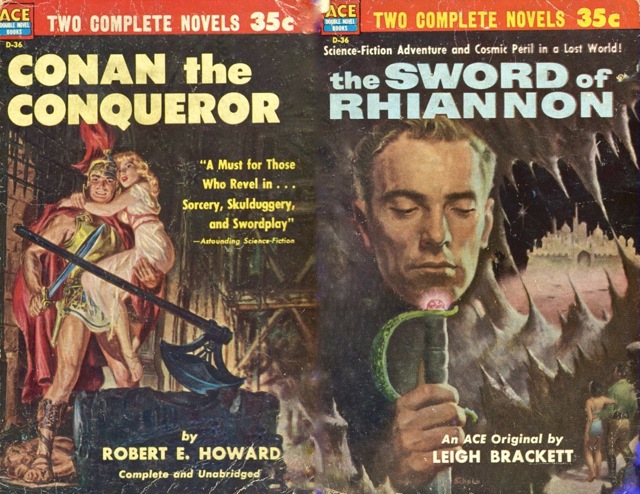

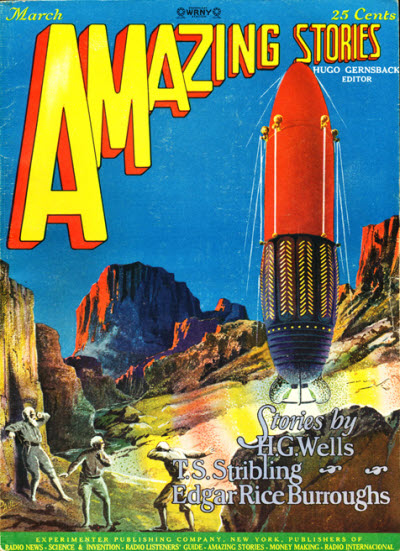

Santaroga Barrier (Part 1 of 3), by Frank Herbert

by Gray Morrow

Frank Herbert’s new novel Santaroga Barrier begins its three-part serialization in this issue. As usual, I will withhold comment until it’s finished. A cursory rummage indicates that it seems to have something to do with people in California taking drugs. It will be interesting to see what Herbert can develop from such an unlikely premise.

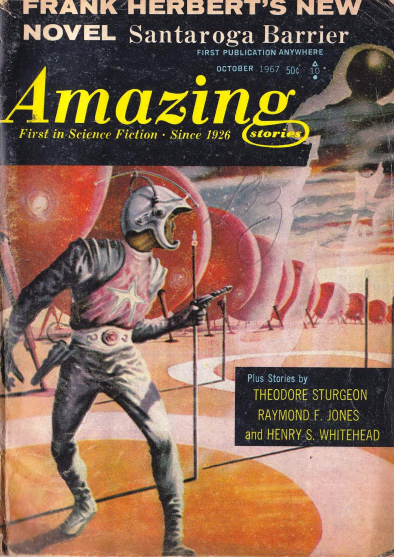

The Children's Room, by Raymond F. Jones

Raymond F. Jones is the very model of a modern science fiction writer. He checks all the boxes. His career is so generic as to be paradigmatic, or maybe vice versa. He started out in Campbell’s Astounding, just in time to join new writers George O. Smith and Hal Clement and retread Murray Leinster in keeping that magazine going when such mainstays as Heinlein, Hubbard, Williamson, and de Camp were lost to military service or war work. After the war, when paper shortages loosened and the pulps returned from wartime quarterly schedules to monthly or bimonthly, Jones—along with Theodore Sturgeon, A.E. van Vogt, George O. Smith and other Astounding writers—began helping to fill them as well as continuing to appear in Astounding. When specialty publishers began to muster the large backlog of magazine SF for book publication, Jones was there with his Astounding novel Renaissance and a collection of his 1940s stories, The Toymaker. When Galaxy appeared in 1950 and instantly broadened the range of the field, Jones contributed the shocking A Stone and a Spear, which would likely have been unpublishable anywhere else. When “juvenile” (the term is becoming “young adult”) science fiction became a big item, Jones provided the well-remembered Son of the Stars and its sequel Planet of Light to the John C. Winston series. When SF started to be big box office, Jones’s novel This Island Earth was turned into a mediocre but high-profile movie. But somehow his recognition never kept pace with his resume, and now he seems to have given up and been largely forgotten, with only five new stories since 1960.

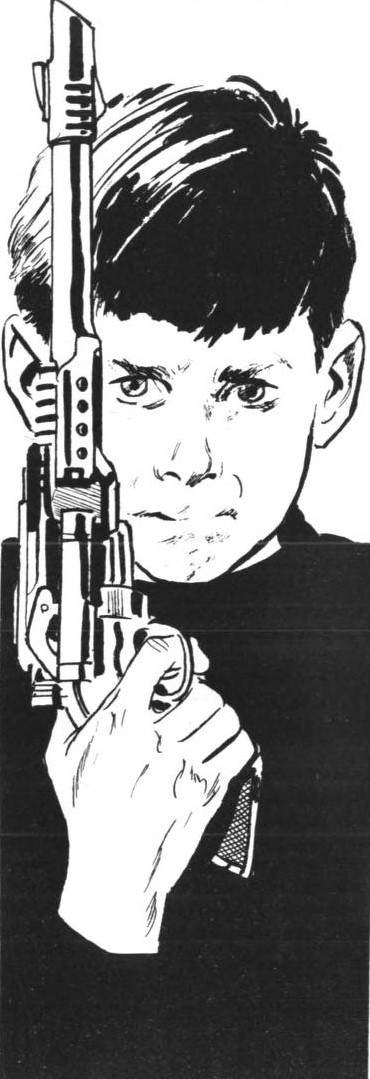

The Children’s Room, from the September 1947 Fantastic Adventures, is only the third story Jones published outside Astounding. It’s about super-people—hardly an unusual theme in that magazine—but it pursues some of the implications of that idea that Campbell may not have found too palatable. Bill Starbuck, chief engineer at an electronics company, picks up one of the books his IQ-240 son checked out from the university library’s children’s room, and finds himself captivated by a particularly subtle fairy tale. Next day the kid is sick and the book is due so he returns it, only to be told “We have no children’s department.” But on the way out, he sees the children’s room, returns the book, and the librarian there (having learned that Bill has read the book), gives him more to take home.

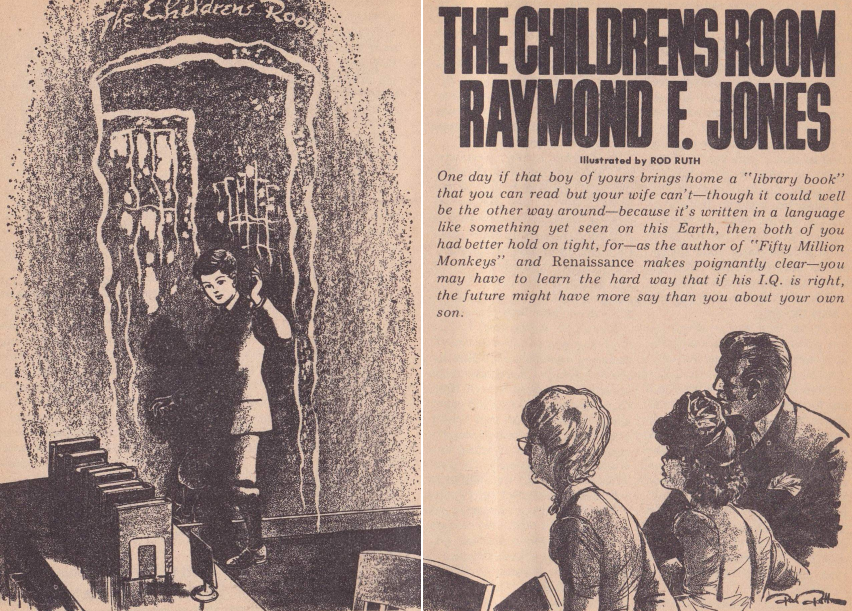

by Rod Ruth

So what gives? Time-traveling mutant super-people, of course—what else? In the future, humanity is up against an alien species that is out-evolving them! So they must scour the past for those people with beneficial mutations who never had a chance to amount to much, contact them and get them used to their exalted status (groom them, you might say), and then carry them off to their grand destiny in the future, never to see their time or their families again. Only the mutants can even read the books, or see the time travellers’ children’s rooms. Bill’s an exception—he can read the books and see the rooms, but has none of the other talents of the mutants, so he’s not invited to the future; and Mom’s a total loss.

So the kid gets on board with the plan, and the parents both come around, since there’s not much else they can do. But there’s a consolation prize for the parents (otherwise they would have a lot of ‘splainin’ to do to the Bureau of Child Welfare), and here Jones twists the knife in this formerly mild story. (Read it and see.) Or, about as likely, Jones is just naively working out the plot, and it is only we mutants reading it who can perceive its monstrousness. As, no doubt, Campbell did, and rejected the story, or so I surmise. Four stars, even if the fourth may have been accidental on Jones’s part.

Five Years in the Marmalade, by Geoff St. Reynard

by Bill Terry

Geoff St. Reynard, a pseudonym of Robert W. Krepps, contributes Five Years in the Marmalade (Fantastic Adventures, July 1949), an inane joke. Two guys walk into a bar—Muleath and Dangeur, who just returned from Alpha Centauri—and after they’ve had a drink, a Martian teleports in, just returned from a stay on Mercury. The boys call him over, and he tells them about his “single-trav,” which will take him anywhere he can think of, through (of course) the power of thought. So they recommend he head off next to Marmalade, which Muleath has made up and which exists only in his brain. Connect the dots. It's as skillfully executed as it is silly, and remarkably, Everett F. Bleiler and T.E. Dikty thought enough of it to put it in The Best Science Fiction Stories: 1950. Two stars, barely.

The Siren Sounds at Midnight, by Frank M. Robinson

Frank M. Robinson’s The Siren Sounds at Midnight (Fantastic, November-December 1953) is entirely contrived: “they” have set a midnight deadline to resolve “their” differences, and if things don’t work out, the bombs will be flying and it’s all over for everybody, or close to it. The story is redeemed by Robinson’s quiet good writing, following a long-married couple as they spend what may be their last hours together. Three stars.

Largo, by Theodore Sturgeon

“More lyrical science fiction from the typewriter of Theodore Sturgeon,” says the blurb for Largo (Fantastic Adventures, July 1947). All those terms are debatable except probably “typewriter.” Here’s the alleged science involved, from the opening of the story: “The chandeliers on the eighty-first floor of the Empire State Building swung wildly without any reason. A company of soldiers marched over a new, well-built bridge, and it collapsed. Enrico Caruso filled his lungs and sang, and the crystal glass before him shattered.”

The style is not so much lyrical as swaggering and demonstrative. Here’s the next stretch of text:

“And Vernon Drecksall composed his Largo.

“He composed it in hotel rooms and scored it on trains and ships, and it took more than twenty-two years. He started it in the days when smoke hung over the city, because factories used coal instead of broadcast power; when men spoke to men over wires and never saw each other’s faces; when the nations of earth were ruled by the greed of a man or the greed of men. During the Thirty Days War and the Great Change which followed it, he labored; and he finished it on the day of his death.”

by Henry Sharp

That is, “I’m gonna tell you a story and I’m just the guy who can do it.” And, of course, Sturgeon is that guy, on his better days. The striking thing about this story is the conspicuous confidence and cadence with which he lays out what is actually a pretty hackneyed plot—an extravagant revenge drama. Drecksall is an eccentric musical genius with an all-consuming work in progress. He works at menial jobs so support himself and his violin. Then he falls in love with the beautiful but vapid Gretel. A crassly entrepreneurial type, Wylie, recognizes his genius, exploits it and him, and also ends up marrying Gretel himself. Drecksall continues to perfect his Largo, though it’s sounding darker all the time. He builds his own auditorium to perform it in, invites Gretel and Wylie to hear it, and then . . . fade to black.

There’s more, but it’s all in the telling, which is worth reading as a conspicuous demonstration of craft if nothing else. This is Sturgeon’s fourth SF or fantasy story to be published by someone other than John Campbell, and it contrasts sharply to Blabbermouth, the second such, from Fantastic Adventures a few months earlier. That one was told in an off-the-rack style that fit Sturgeon like an embarrassing Hallowe’en costume. This is Sturgeon being himself, performing a circus act of the redemption of hokum by style. Splitting the difference, three stars.

Scar-Tissue, by Henry S. Whitehead

by Robert Fuqua

The antique of the bunch is Henry S. Whitehead’s Scar-Tissue, which came from the July 1946 Amazing, but was posthumously published; the author died in 1932. It begins unpromisingly, with the narrator asking his friend the ship’s doctor, “What is your opinion on the Atlantis question?” This becomes a frame story in which one Joe Smith, with Harvard and Oxford’s Balliol College on his resume, describes his past lives in prehistoric times, in Africa under the Portuguese (“Zim-baub-weh,” the place was called), and then Atlantis, where he was a gladiator, and he’s got scars to prove it. It’s a perfectly readable old-fashioned story. Three stars.

Summing Up

Not bad, a readable issue of this ill-conceived incarnation of Amazing, and better than not bad if the Herbert serial pans out. We'll see.

![[September 6, 1967] New Look, New . . . ? (October 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/amz-1067-cover-394x372.png)

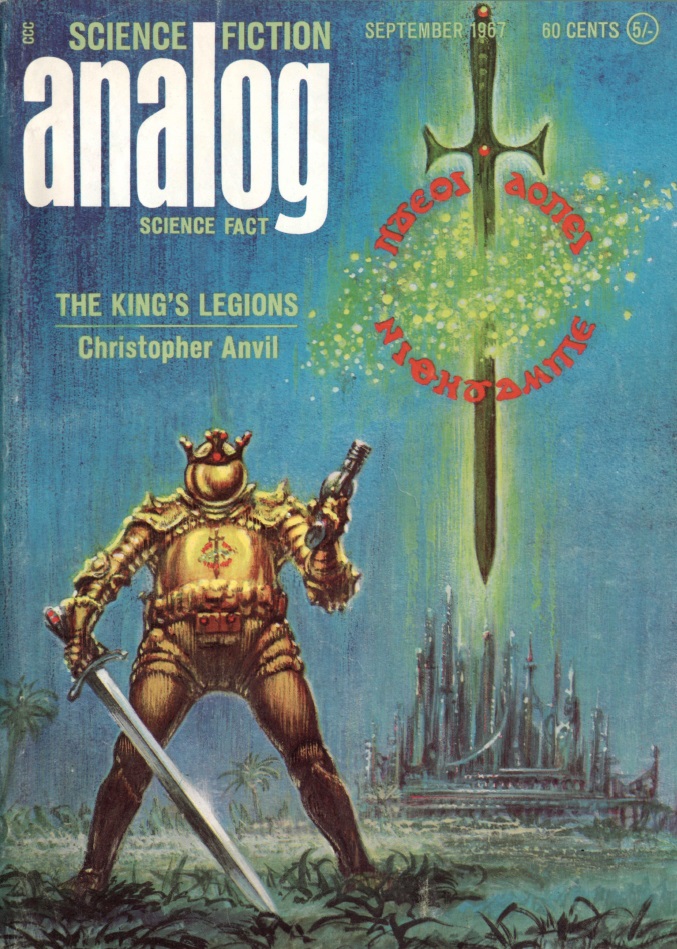

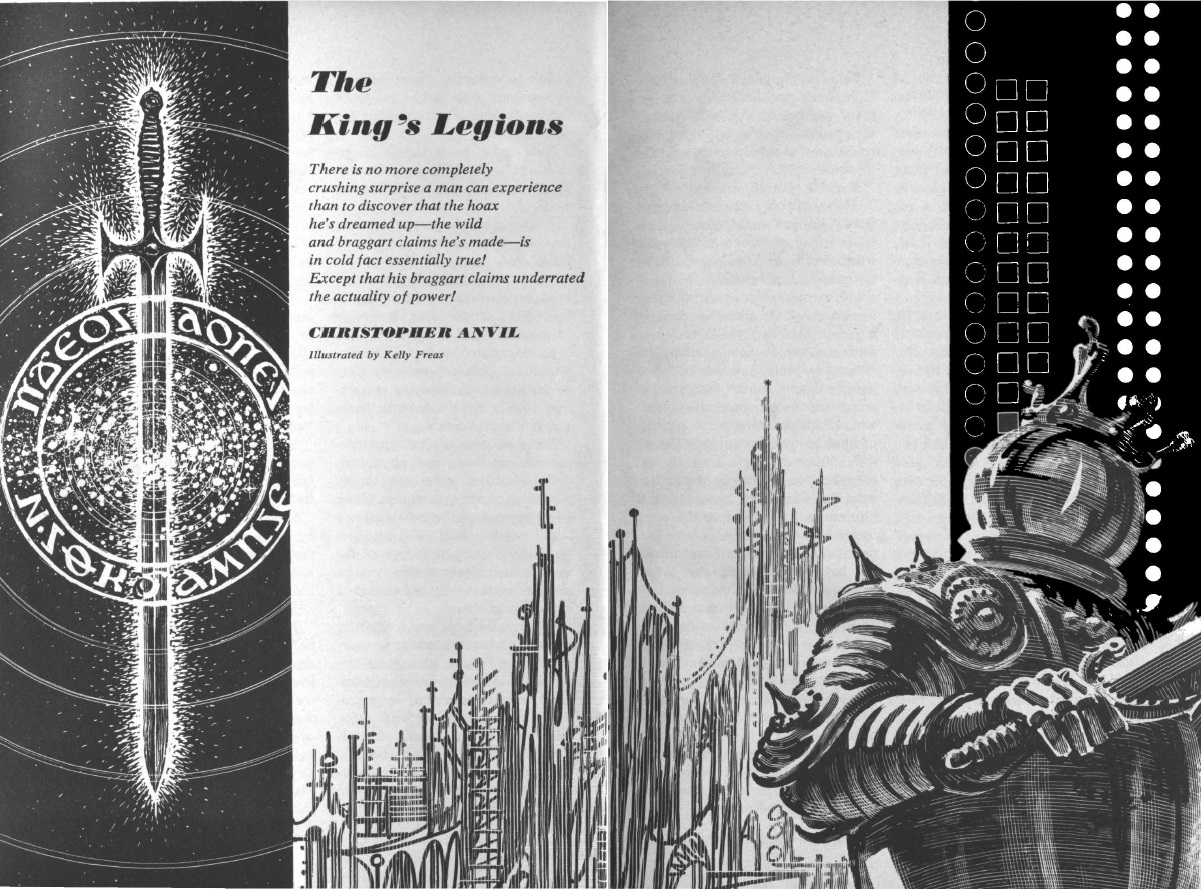

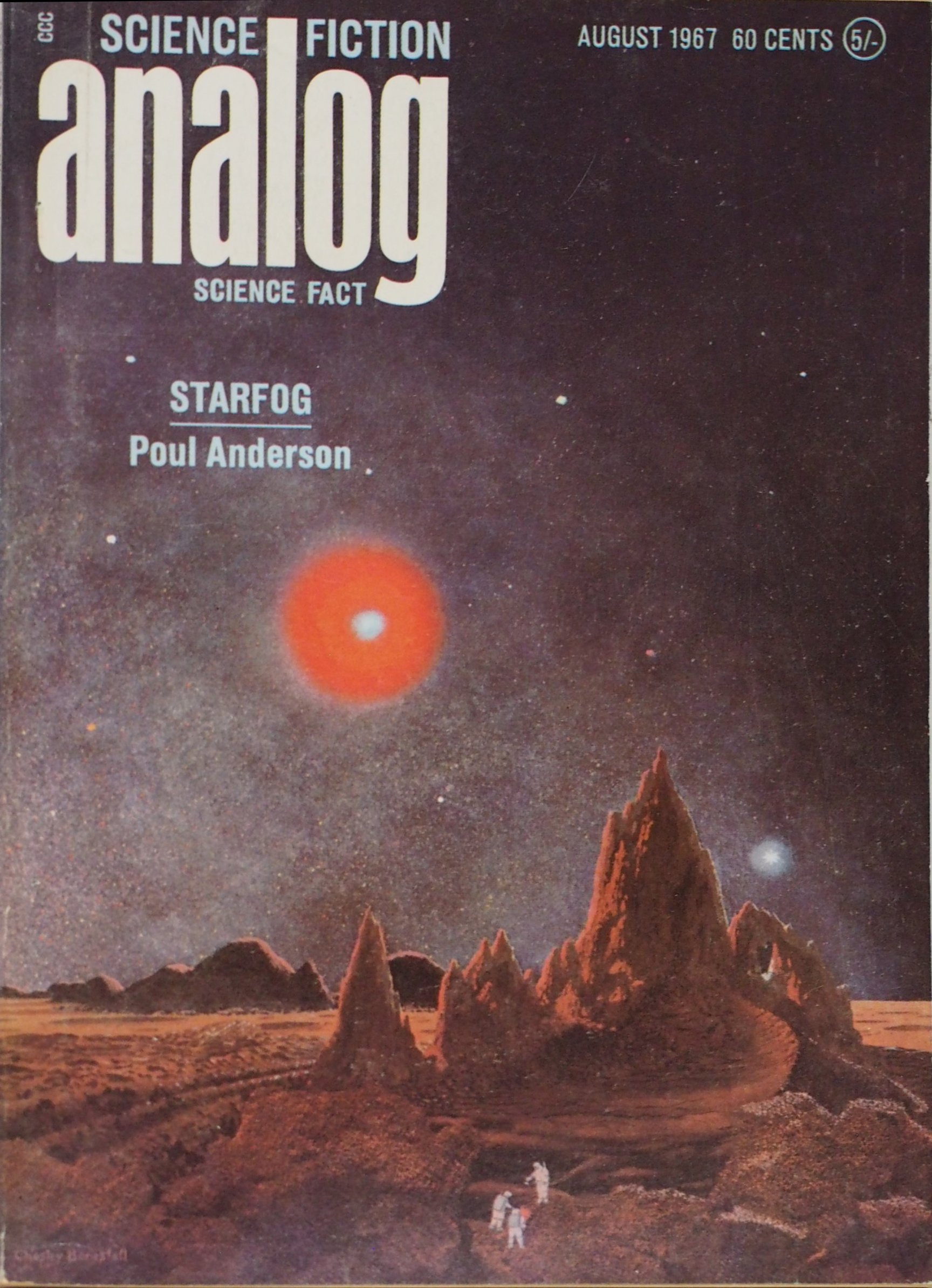

![[August 31, 1967] I wouldn't send a knight out on a dog like this… (September 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670831cover-672x372.jpg)

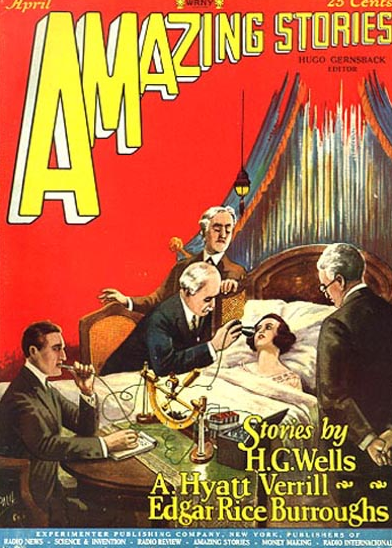

![[August 20, 1967] Hugo Gernsback, 1884-1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/gernsback-1929-486x372.png)

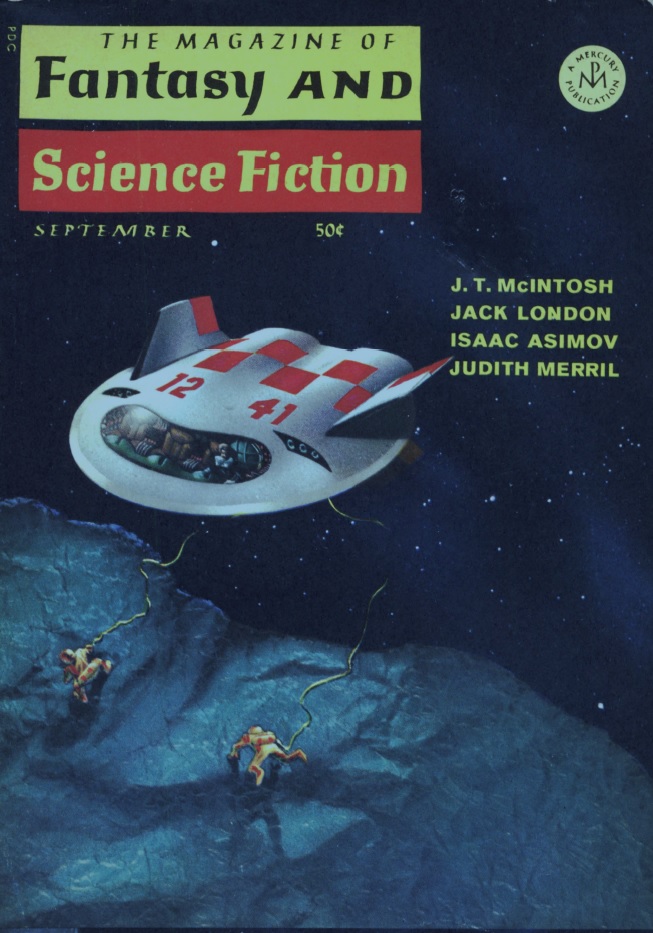

![[August 18, 1967] The Best and the Brightest? (September 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670818cover-653x372.jpg)

![[August 12, 1967] Planetary Adventures (August 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670812covers-672x372.jpg)

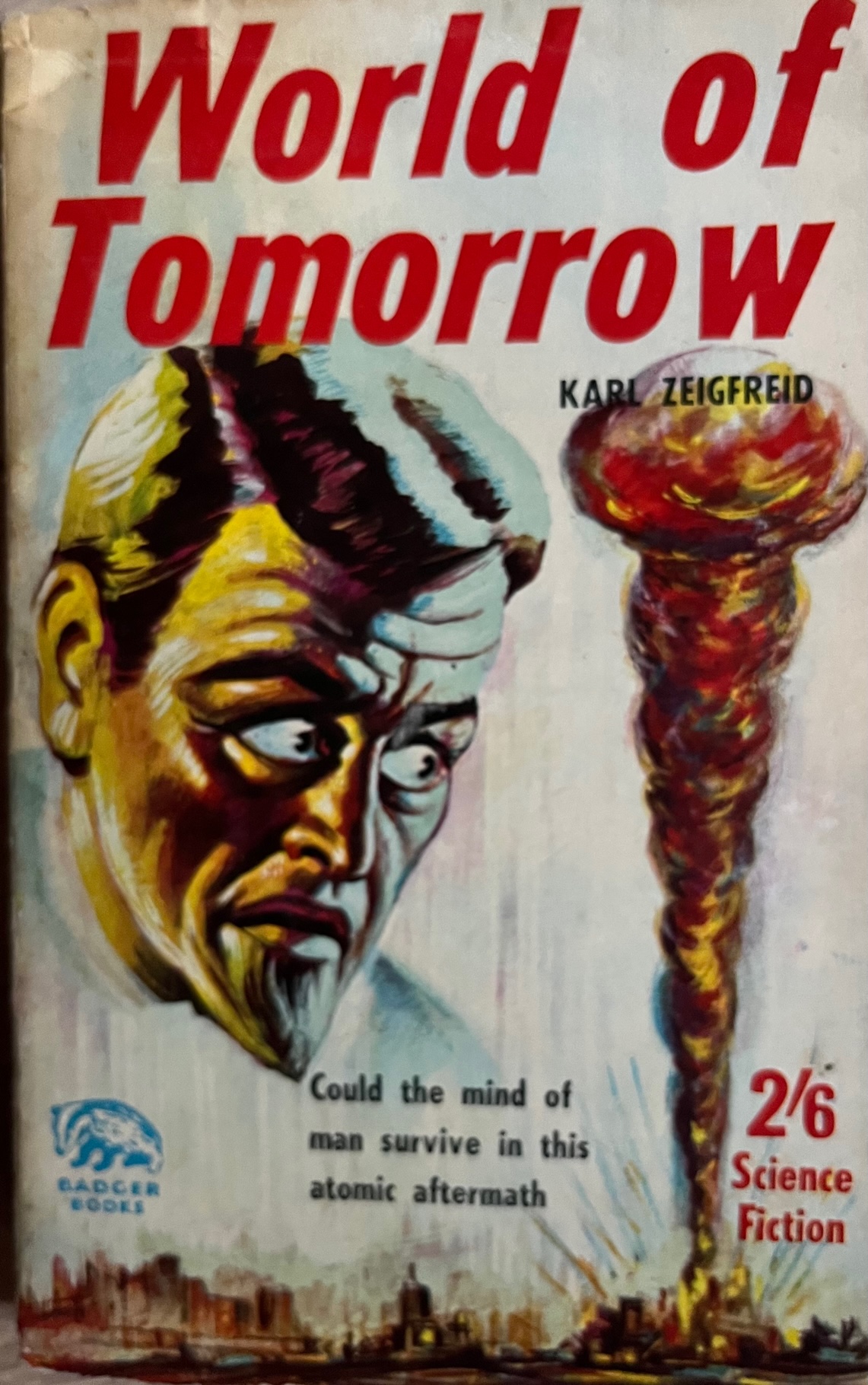

![[August 10, 1967] Badger Books: A Farewell and an Introduction](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/IMG_6354-672x372.jpg)

This is what we're losing.

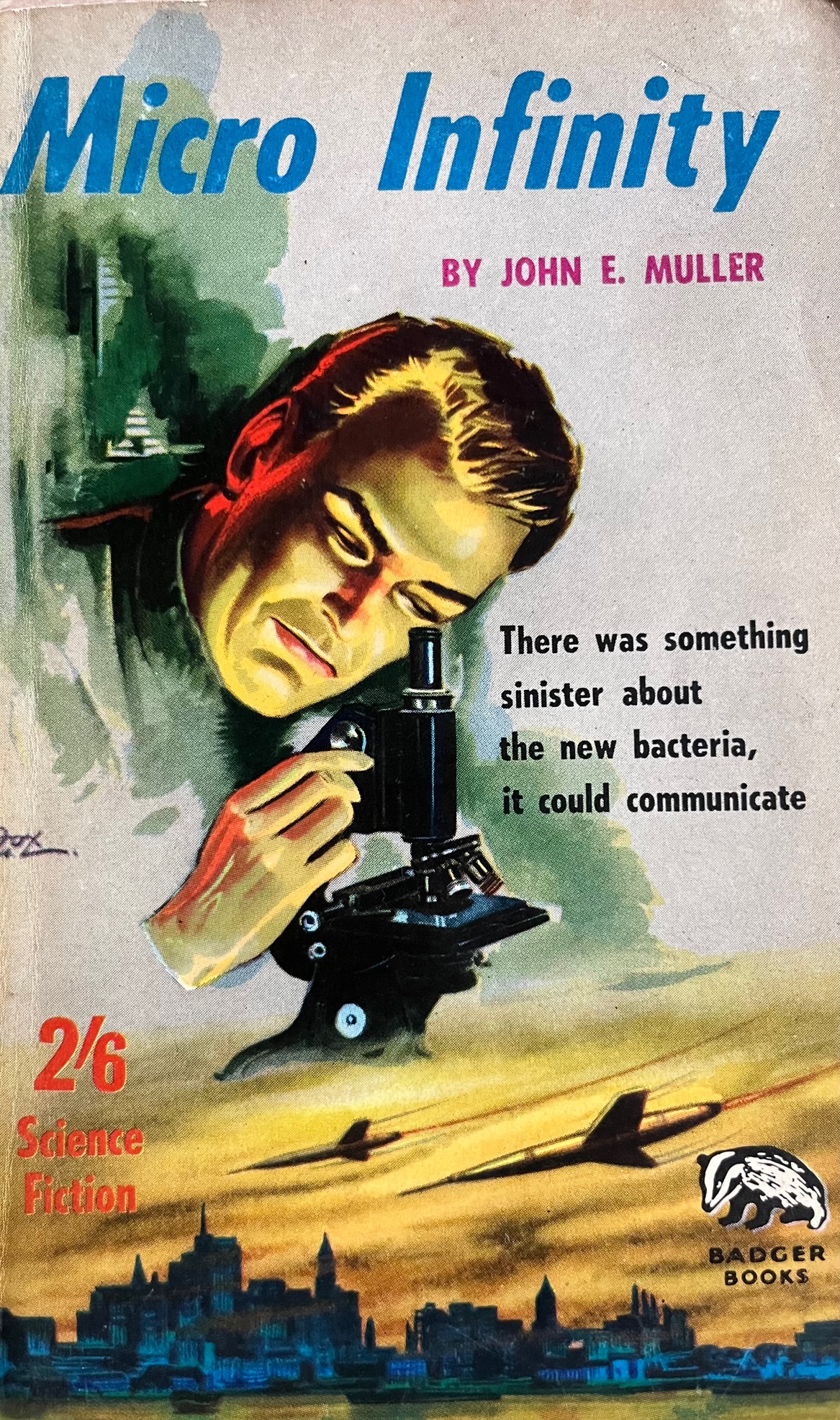

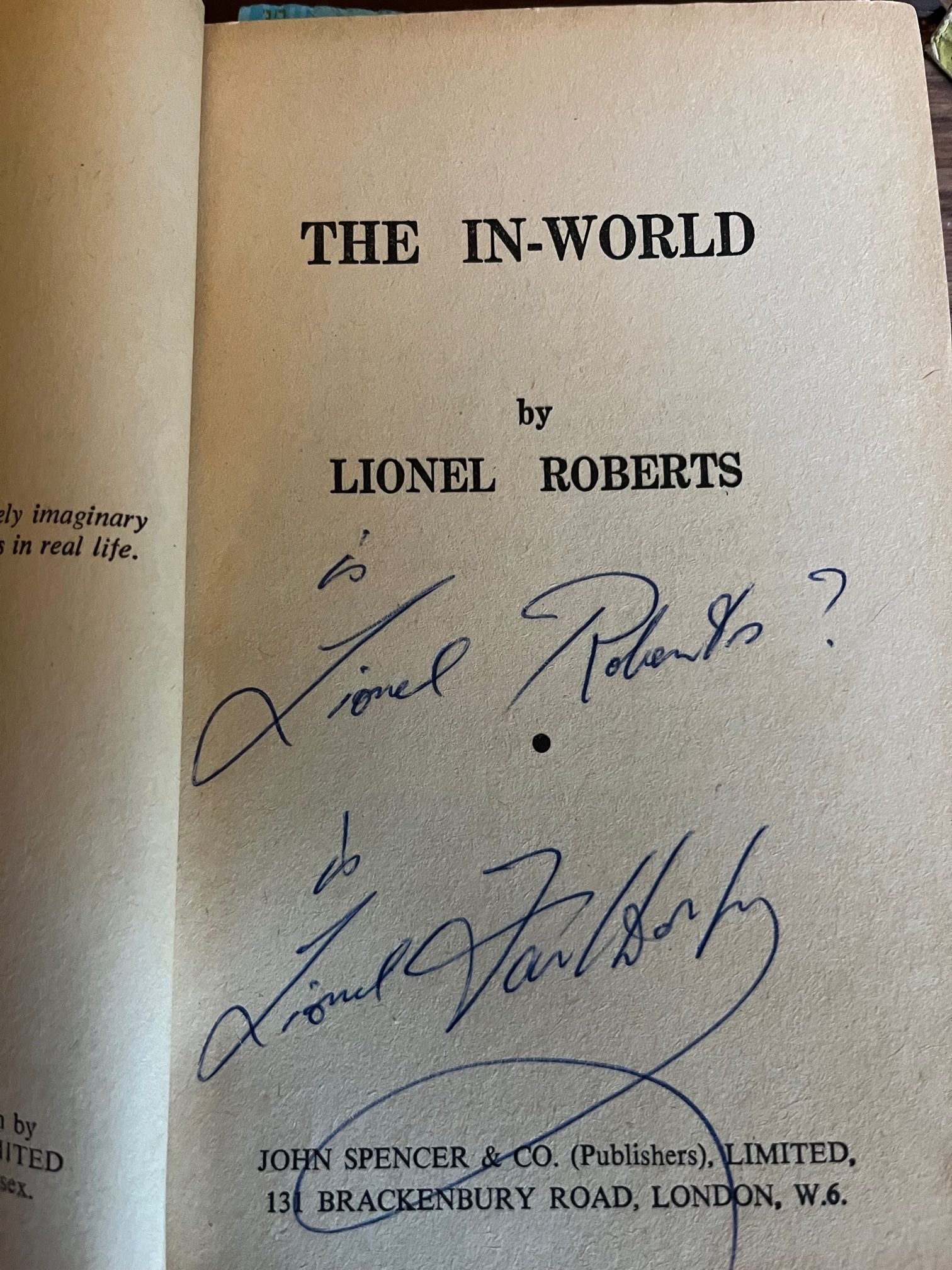

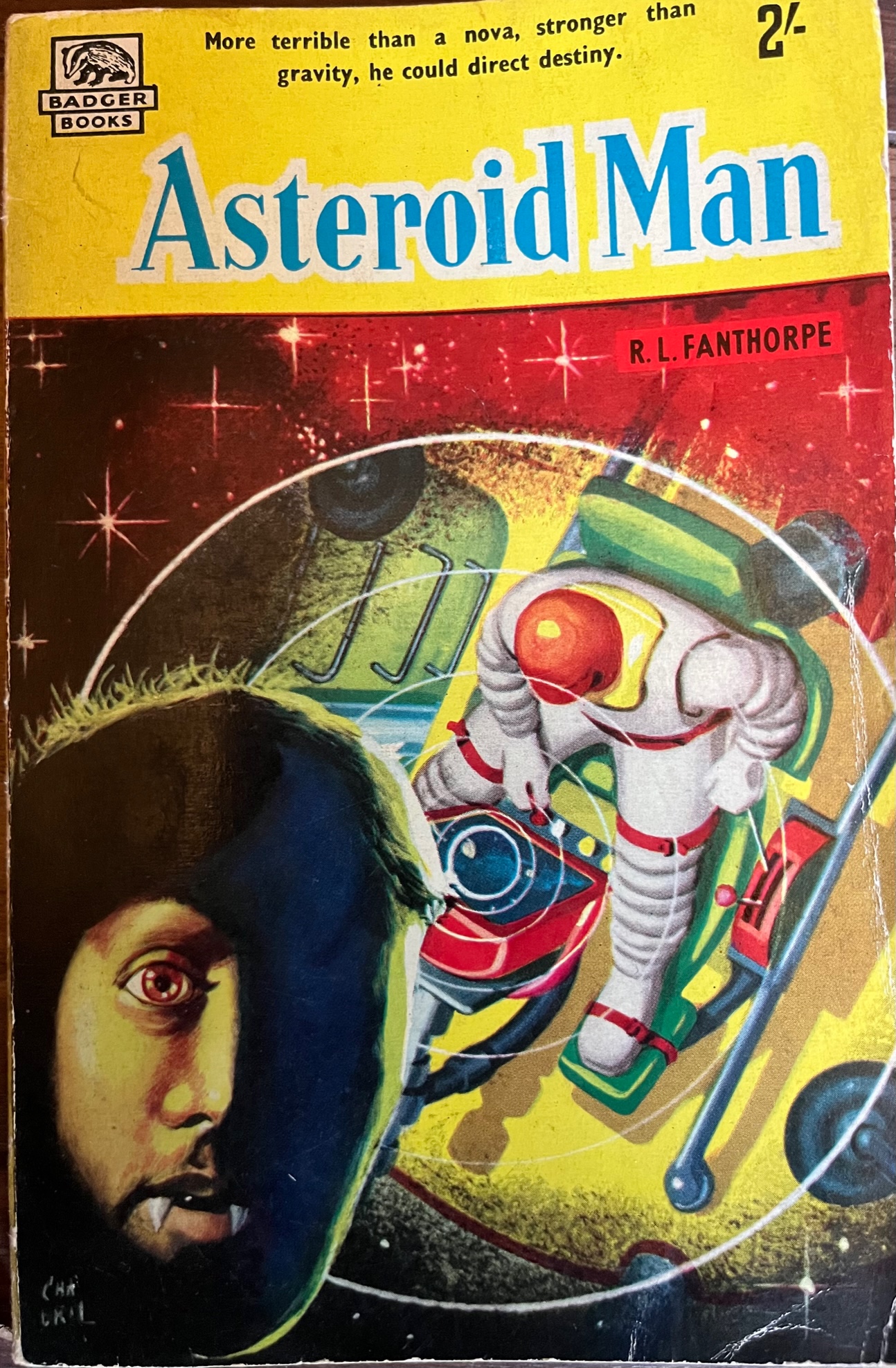

This is what we're losing. Even Mr Fanthorpe isn't always sure who he is

Even Mr Fanthorpe isn't always sure who he is Knowledgeable readers may be able to identify the source.

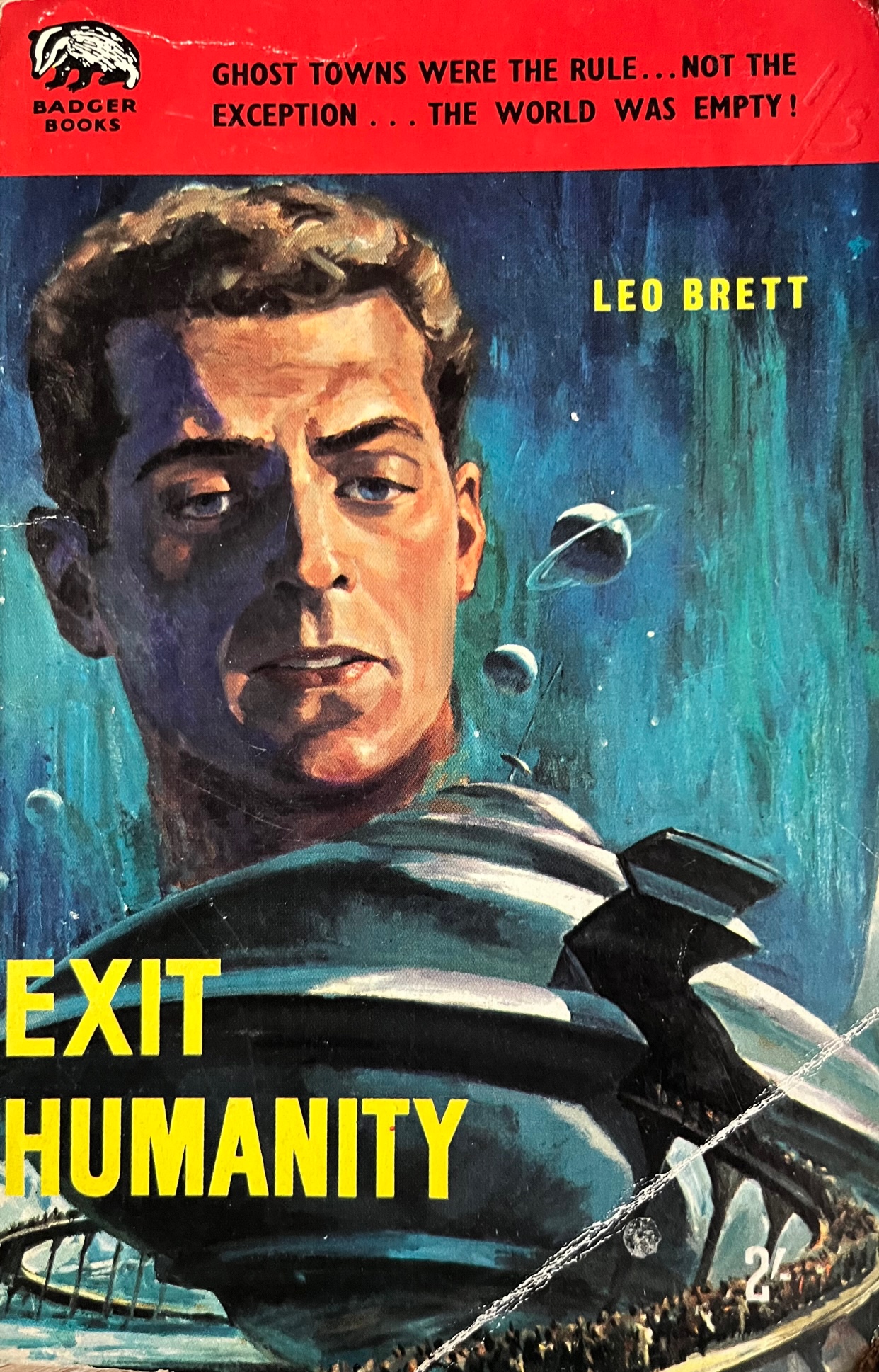

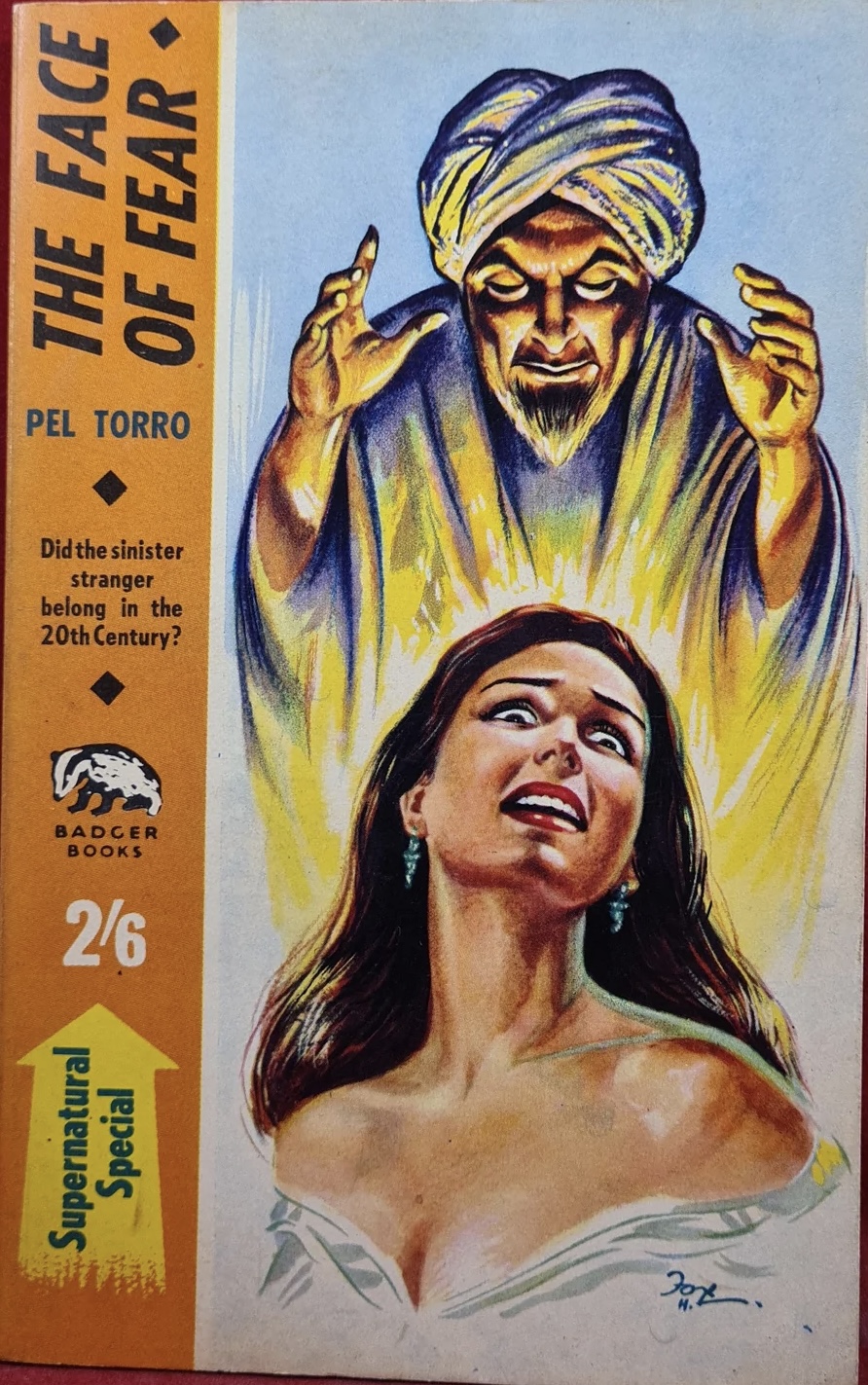

Knowledgeable readers may be able to identify the source. Yes, this really says "medieval China" to me too.

Yes, this really says "medieval China" to me too. Don't expect it to make sense.

Don't expect it to make sense. And yes, Fang Guy really *is* in the story.

And yes, Fang Guy really *is* in the story. He's a fake fakir.

He's a fake fakir. Yes, this really happened.

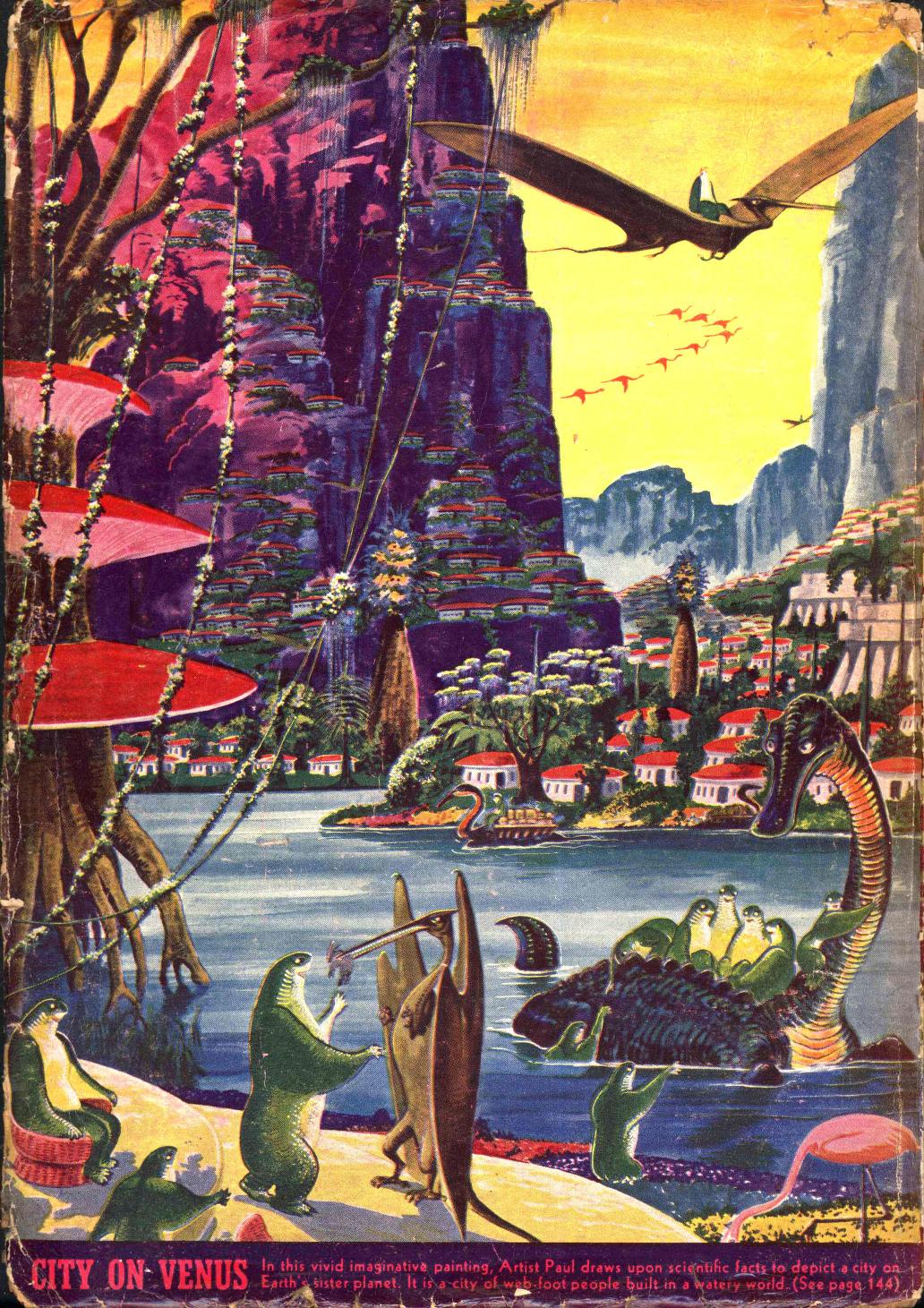

Yes, this really happened.![[August 8, 1967] Distant Signals (September 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Fantastic_v17n01_1967-09_0000-2-672x372.jpg)

![[July 31, 1967] Canceling waves (August 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670731cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 20, 1967] An Analog of <i>Analog</i> (August 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670720cover-659x372.jpg)

![[July 18, 1967] Highs and Lows (July Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670718covers-672x372.jpg)