by Tam Phan (Secret Asian Man)

Nichelle Nichols is a delight so it’s always exciting to see Uhura on the bridge in the opening scene, and after Walter Koenig’s performance in the last episode, I was really looking forward to more Chekov. When they were both called to be part of the landing crew at Gamma II, my hopes were high that this might be a repeat performance of “I, Mudd”. Unfortunately, “The Gamesters of Triskelion” featured William Shatner, and little else.

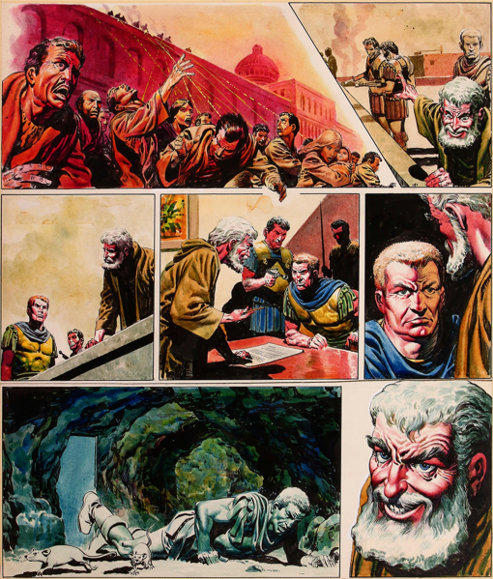

Immediately after stepping on the transporter platform, Kirk and the party were abruptly teleported away by an unknown force. They were met by hostiles on a planet that was clearly not Gamma II. While Uhura and Chekov were quickly captured, Kirk went on to not just best his opponent, but continue to fight until he was blindsided by another hostile. Upon which, they were greeted by, “Galt, master thrall of the planet Triskelion” who is tasked with training those that have been abducted by The Providers.

"All I want for Christmas is a pair of arms."

Meanwhile, on the Enterprise, Spock, McCoy, and Scotty are doing everything they can to figure out what happened to their captain and crewmates. In their typical way, Spock and McCoy share a moment of banter that adds some levity to the situation as their search continues. The interactions on the Enterprise continue to escalate as McCoy and Scotty disagree with Spock following a trail leading them nearly a dozen light years away from Gamma II. It’s not uncommon for McCoy to be at odds with Spock, but Scotty usually has a good head on his shoulders when it comes to command. This was not one of those times. As commanding officer, and apparently the only person currently with any sense, Spock continues to follow the trail that, you’ve already guessed, eventually leads to Triskelion.

"Have you looked under your bed, Spock? How about on Mars? We should check all the angles before following your hunch. Who do you think you are? The acting-captain?"

On Triskelion, Kirk, Uhura, and Chekov attempt to escape but quickly discover that the collars they wear are not fashionable accessories, but a means to correct and control them. A few questionable interactions later we find Kirk seducing his Barbarella-esque drill thrall, imposing his sense of western morality, and then exercising his physical prowess yet again. (Let’s be honest, there are a few questionable interactions during this scene as well.)

“What is so questionable,” you might ask? It wasn’t enough that one of the thralls enters Uhura’s chambers and we are left to wonder if something horribly indecent is happening over an entire commercial break, but a bound black man is brought out to be an exercise dummy during their training. That is until Kirk comes to the rescue and redirects the torture onto himself and is resurrected… sorry, wrong story… proceeds to defeat his torturer, a thrall that is quite literally twice his size, by strangling him from behind. I may not be a martial artist (well, okay, I am) but it doesn’t seem like Kirk took much advantage of the brute’s weak left eye, as he was advised to do. Obviously, dispatching armed opponents twice his size is just a day in the life of David. I’m sorry, I keep getting my stories mixed up. Must be all the biblical references Spock keeps making (apparently Vulcans don't have their own bible.)

"You do realize how tacky this is, right?"

The Providers are so impressed that they have a bidding war over who gets to own the “newcomers” and at this point, it shouldn’t be lost on anyone that the Providers are slave masters betting on gladiators.

If that wasn’t enough William Shatner for you, he’s featured shirtless and sporting a training harness for the rest of the episode as he charms his battle-hardened drill thrall, attempts to escape, and outsmarts The Providers by agreeing to battle three thralls to free himself, his crew, and the remaining thralls. He wins, of course. Was there any doubt?

"How about a real wager? If I win, I get to dress like this all the time."

Ultimately, the Enterprise reaching Triskelion did nothing but put the rest of the crew in danger, Uhura’s and Chekov’s involvement had little significance to the plot, and Kirk is our savior against an omnipotent being once again.

This is one of the hopefully rare occasions where the writing, directing, and editing failed to deliver. Appropriate with the number of characters featured in this episode, I rate it one star.

The B Team

by Gideon Marcus

Last year, Green Beret Gary Sadler warbled eloquent over the virtues of "Twelve Men, invincible… the A Team". The latest episode of Trek was very definitely the product of The B Team.

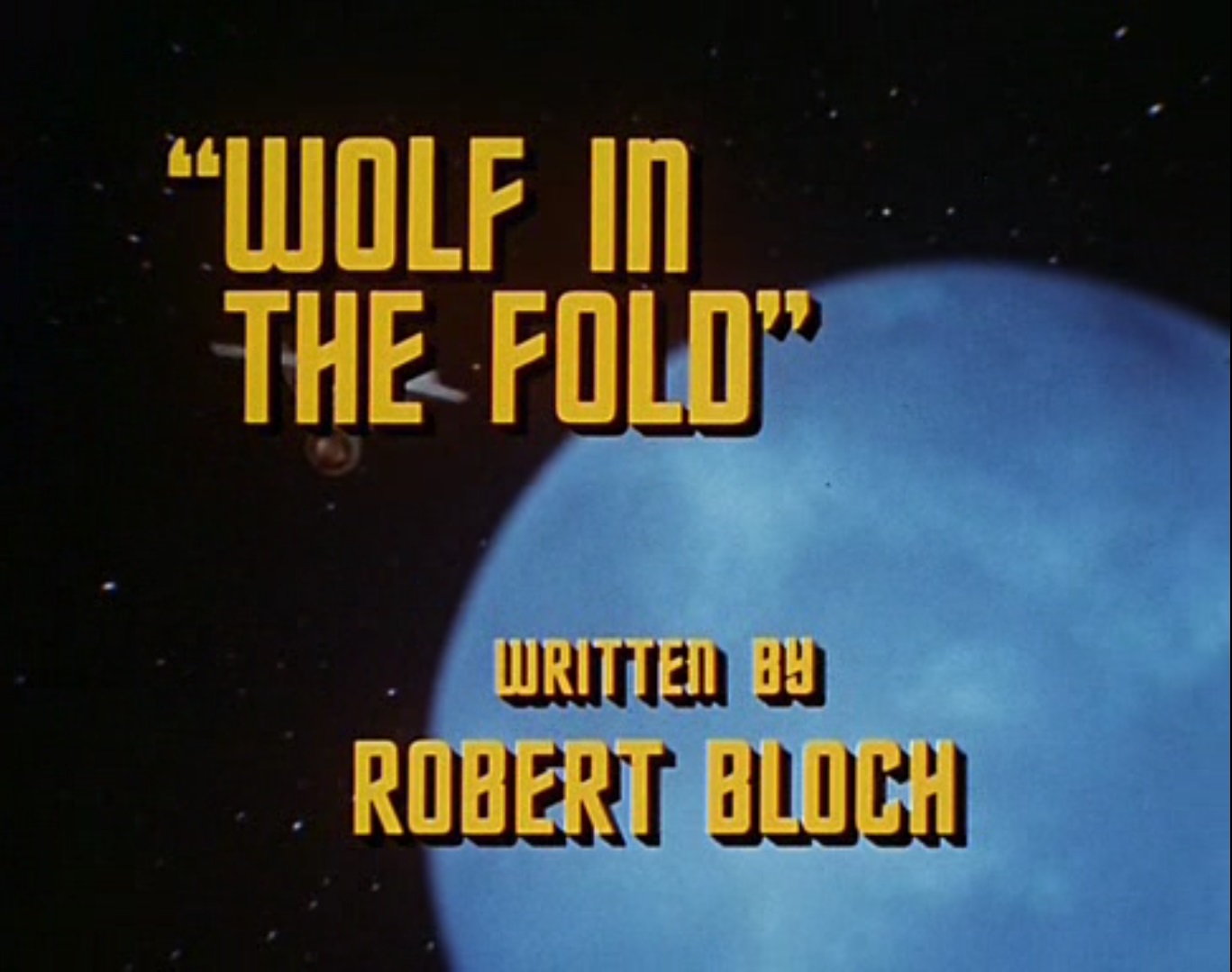

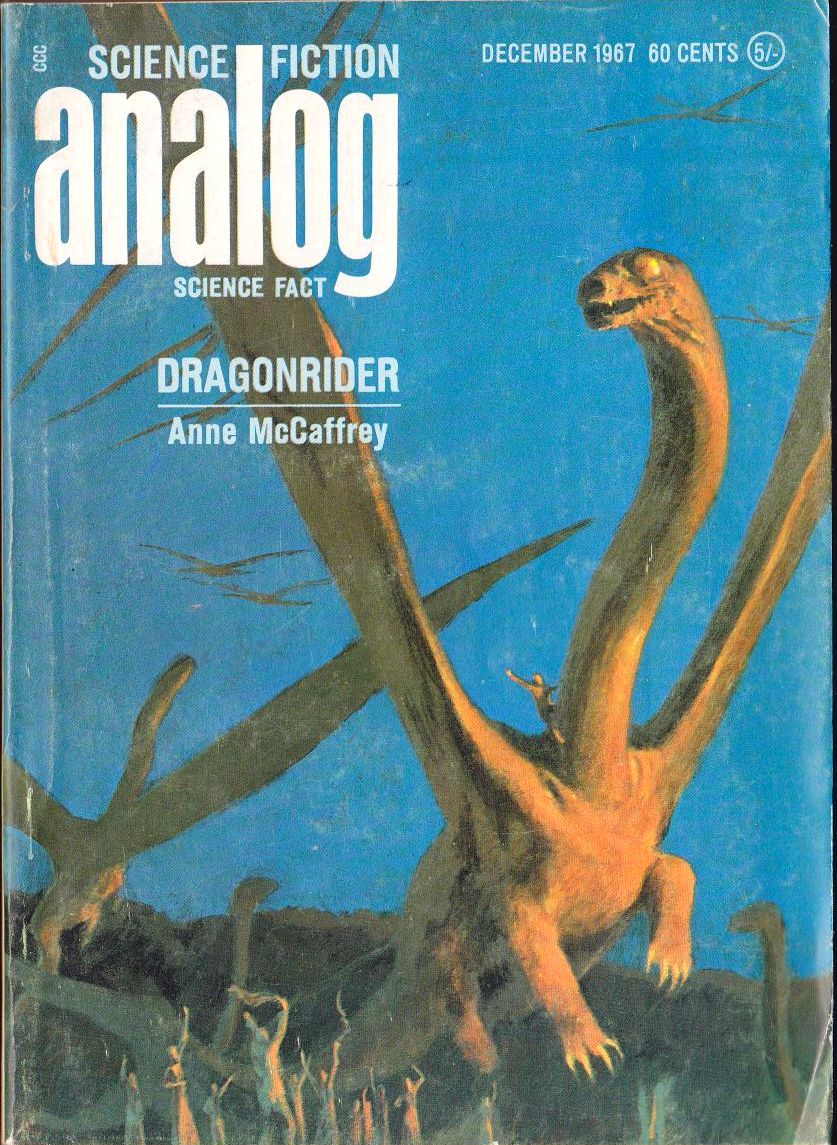

We always scan the credits eagerly at the beginning of each episode. Many is the time we've been treated with the bylines of some of our favorite science fiction authors. Even when one turns in a substandard script ("paging Bob Bloch, Mr. Bob Bloch…"), there's still the thrill of being able to say, "I know that guy!" And if a writer be unknown, the director is often one of a stable of familiar names: Marc Daniels, Joseph Pevney, Ralph Senensky.

This time, we got a script by a "Margaret Armen" and a director named "Gene Nelson". While it's always nice to see the creative wealth spread around, this time the new talent let us down.

For one thing, we've now gotten to the point where writers are portraying caricatures of our favorite characters rather than developing them. In this episode, McCoy and Scotty spend endless hours bickering with acting-Captain Spock. While it's true that McCoy loves to take an adversarial position with respect to the Vulcan, Scotty does not (recall that he was the only one to have no truck with the insubordinate nonsense of "The Galileo Seven".) Uhura and Chekov might as well not even exist, despite a tantalizing promise of activity.

Nichols and Koenig are stunned to learn they won't have any more lines this episode.

Instead, we get Kirk nobly educating the savages and their masters about the virtues of democracy and freedom. Even more, we are treated to every kink and fetish the writer has ever wanted expressed on celluloid. Lurid harnesses from space-age materials, whips, pain collars, and more Shatnerian tongue than we've seen in all the prior episodes combined.

Speaking of Shatner, Gene Nelson's sin is not overdirection but lack of it. Kirk's actor made it clear this summer that he was going to throw in more stylized, personal traits into the captain; Nelson let go of the leash, letting Shatner run wild. The smarmy chuckle, the goggle-eyed outstretched arm and cry (which ends two of the acts), the hunched shoulder and wide-armed delivery, the…punctuated…delivery-of-lines.

Indeed, one wonders if Shatner had anything to do with the script revision process, because if he has any tendency toward line counting, he sure made certain he got 80% of the lines spoken this time around. I like Trek best when it's an ensemble show. This was the Kirk show.

Add to that the entirely recycled score, the recycled costumes, and the recycled sets (we don't even get to see the trinary sun), the recycled plots ("Arena", "Metamorphosis", "Menagerie") and Gamesters ends up a very tired affair.

1.5 stars (I liked the bit between Tamoun and Chekov, and also the fact that Uhura was able to fend off her would-be-rapist all by herself).

Do One Thing and Do it Well

by Joe Reid

I imagine some stories are a lot like people. At some point in their lives men and women must decide who they are going to be. They come to realize that the choice is theirs. If that epiphany doesn’t come to them, they hopefully can accept who they do become, whether by intent or circumstance.

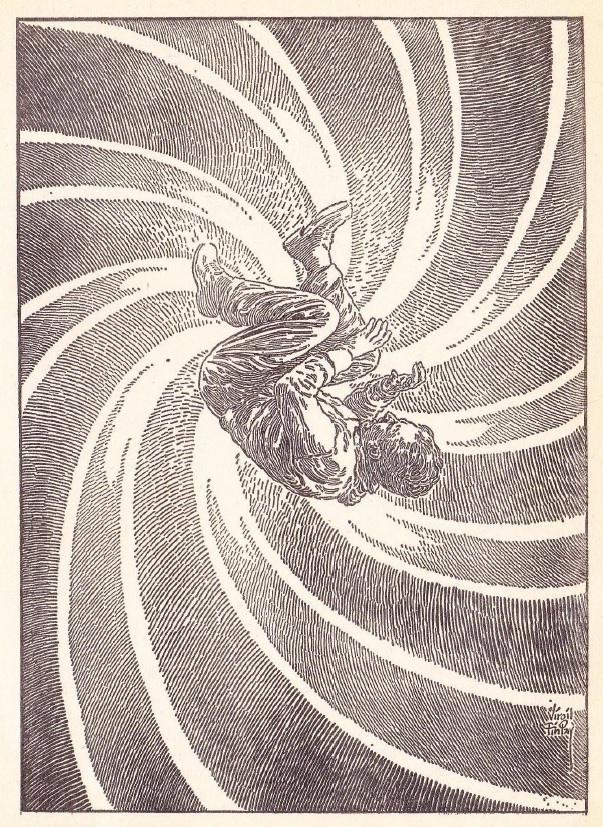

This episode of Star Trek was striving to be something; sadly, it didn’t know what. Did it intend to be a reminder of the wickedness of American chattel slavery, using the crew as the enslaved? Was it trying to be a tale of manipulation of a naive innocent? Perhaps it was an attempted telling of a mutiny on the Enterprise or a gladiator epic on an alien world or an echo of Forbidden Planet?

Knowing my history and seeing free people abducted from their homes, being restrained, and sold as property to me harkens back to the horrific institution of American slavery. If that wasn’t clear enough, two other scenes in the episode drove it home for me. In the first scene, Lars, one of the overseer thralls, attempts to force himself onto Uhura, who being “property” should have no right to refuse his advance. Thankfully, our gal proved she was no helpless damsel. The second scene involved an “alien”, looking unmistakably like a black man, about to be punished for disobedience by another overseer. Uhura again refused to participate in that and was about to be punished in the man’s place, until Kirk stepped in to take her place. These scenes might mean nothing to most people, but to me they clearly reflect our dark national history. They blatantly demonstrated the subject in a way that grade schoolers could understand. Then it suddenly chose to be something else entirely. It became “Svengali”.

Beautiful, young, and inexperienced. A woman is introduced to emotions and feelings she had never felt before by a seductive man. Being violently manipulated by him, so that he could gain access to the hidden players behind the curtain…

"How can you resist me? We're showing virtually the same amount of skin!"

Then it became “Ben Hur”.

“Captain” and his friends are forced to fight for their lives as gladiators for the amusement of powerful rulers, who see them as toys for their entertainment. Can he beat the odds and survive the death games of Triskelion…

Then it became the comic strip “Barbarella”.

A silver-bikini clad minx fights and loves while trying to avoid the wrath of the unfeeling Providers… I’ll stop here.

I found the thematic shifts in the episode jarring. Especially since it attempted the last three things simultaneously, after ceasing to be a slavery epic. I neglected to mention the poor man’s rendition of “The Bounty” back on the Enterprise. An almost-mutiny with comical quips between emotional McCoy and logical Spock which fell flat for me.

This entry, with Five and Dime versions of Ming the Merciless and Deeja Thoris didn’t satisfy. Had this episode tried to be one thing well, instead of many things poorly, it could have been better. Sadly, the excellent characterizations of Uhura and Spock, were forgotten as the thematic layering took hold.

Two stars

Neither Fish nor Fowl

by Janice L. Newman

A couple of weeks ago Robert Bloch attempted to mix supernatural horror with Star Trek’s style of science fiction, with uneven results. “The Gamesters of Triskelion” attempted a fusion of a different genre with science fiction: sword and sorcery, first born in the pulps and lately enjoying a revival. In the right hands, like those of Leigh Brackett, such a mix can be compelling and interesting.

Unfortunately, the author of the “Gamesters of Triskelion” script was not the right hands.

Is "Margaret Armen" actually a pen name for Jon Norman?

Simply throwing various elements from popular sword and sorcery stories into a blender does not make what comes out at the end a classic, especially when the elements chosen are: slavery, gladiatorial-style games, hand-to-hand combat with primitive weapons, grotesque yet humanoid monsters, physical punishments via whips, ‘magical’ punishments via devices, an evil ‘wizard’, and a naive maiden warrior who must be ‘taught’ what ‘love’ is.

Nor does taking various elements from Star Trek and throwing them into a blender make a good Star Trek episode. McCoy being intransigent with Spock, Kirk seducing a beautiful woman to secure his escape, Kirk getting his shirt ripped off, Kirk fighting a death match to the exciting strains of the “Amok Time” score…these have all been used to more or less good effect in previous episodes. Sadly, here they felt nonsensical, annoying, and contrived – to the point that the episode felt more like a piece an amateur might write for a fanzine than a polished script for a nationally-broadcast TV show.

In the end the result is neither a good sword and sorcery story nor a good Star Trek story.

One star.

Next episode might be better – don't miss Thoroughly Modern Billy (Shatner)!

Join us tonight at 5:00 PM Pacific (8:00 Eastern) or at 8:00 PM Pacific (11:00 Eastern)!

![[January 12, 1968] Shatner Trek: Arena of Triskelion (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Gamesters of Triskelion")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680112title-672x372.jpg)

![[January 10, 1968] Saving the Best For Last (<i>Dangerous Visions</i>, Part Three)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/1967_Dangerous-Visions-hc-672x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1968] Seeing Double…Again (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Enemy Of The World [Part 1])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680108seeingdouble-672x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1968] How much for that fuzzy in the window? (<i>Star Trek</i>: The Trouble with Tribbles")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680104title-672x372.jpg)

![[December 31, 1967] Surprise, surprise! (January 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671231cover-669x372.jpg)

![[December 28, 1967] Stumbling Bloch (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Wolf in the Fold")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671228title-672x372.jpg)

![[December 24, 1967] Hit Parade '67 (the year's best science fiction)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671224galaxy-624x372.jpg)

![[December 22, 1967] In all the old familiar places (<i>Star Trek</i>: "Obsession")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671222title-672x372.jpg)

![[December 20, 1967] Smut! (January 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671220cover-672x372.jpg)

![[December 18, 1967] God Out Of The Machine (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Ice Warriors [Part 2])](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671218wouldyouliketobuyavaccuumcleaner-672x372.jpg)