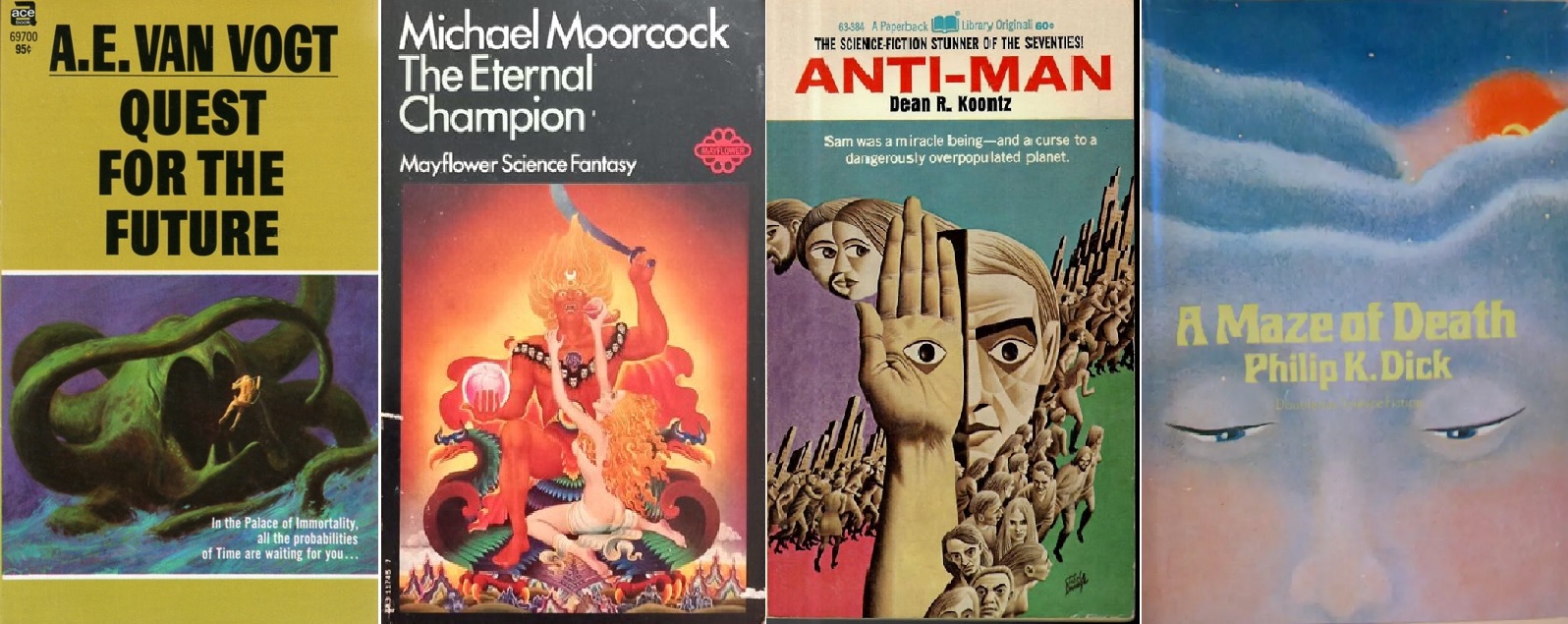

For our second of July's Galactoscopes, we have quite the mixed bag: two winners and two losers. Aren't you glad you've got us to navigate the dross for you?

For our second of July's Galactoscopes, we have quite the mixed bag: two winners and two losers. Aren't you glad you've got us to navigate the dross for you?

So many books this month, and this time, we've got all superlatives. Check out the second June Galactoscope!

Continue reading [June 17, 1970] Time and Again (June Galactoscope Part Two!)

by John Boston

Let’s be up front. That is, the front of the March 1970 Amazing, depicting a space-suited person with outstretched arms following or yearning after or paying homage to an apparently departing spacecraft. The contents page says it’s by Willis, illustrating a story called “Breaking Point.” However, Ted White’s editorial says, first, that he’s contacted some “promising young artists” whose work will appear on future covers, but right now they’re “sifting” the European covers that they apparently buy in bulk and having stories written around them “whenever possible,” like Greg Benford’s “Sons of Man” a couple of issues ago. And this issue’s “Breaking Point” was written around the present cover, so the story illustrates the cover rather than vice versa.

by Willis

And now that we have that straight, who’s this Willis guy? Well, informed rumor has it that the cover is actually by our very familiar friend Johnny Bruck, from the German Perry Rhodan #201 from 1965. The style and subject matter certainly look like Bruck’s.

Moving on to more straightforward matters: the contents look much like the previous White issues, with a serial installment, several new short stories plus a reprint, editorial, book reviews, fanzine reviews, and letter column.

Continue reading [February 12, 1970] Up Front (March 1970 Amazing)

by John Boston

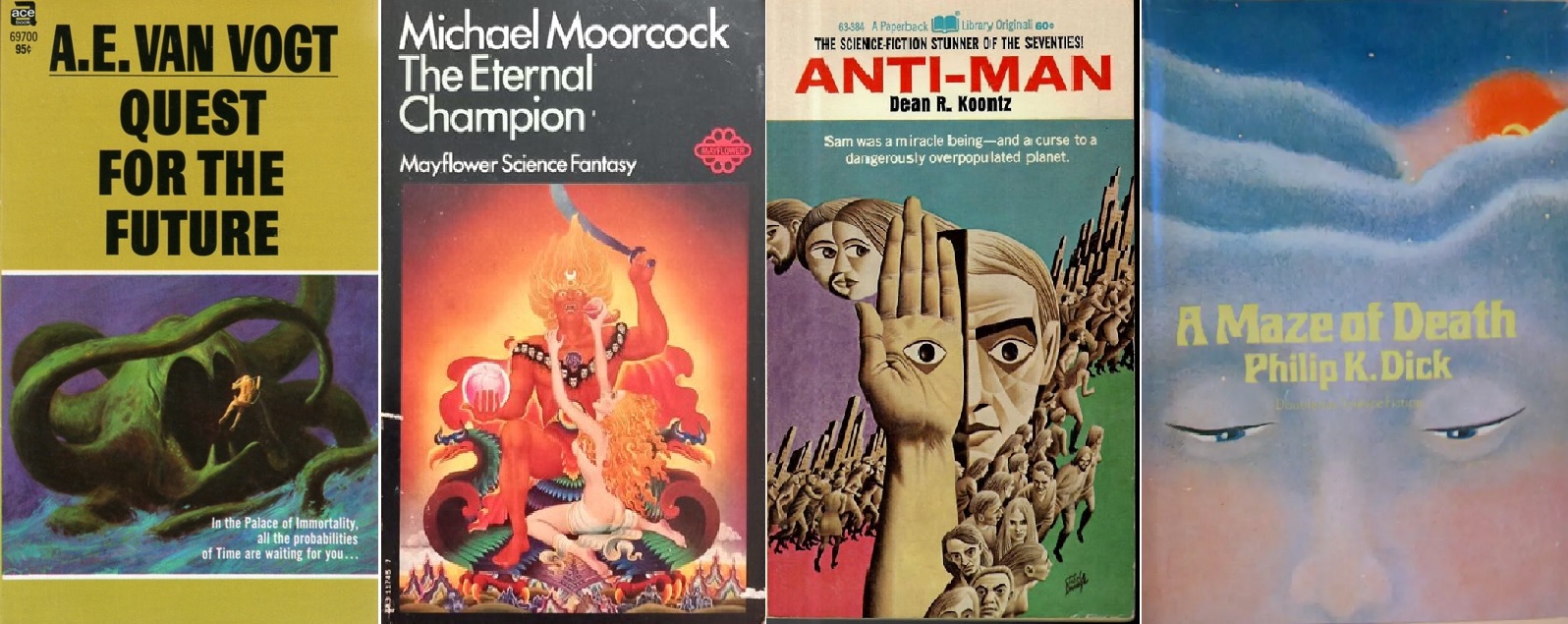

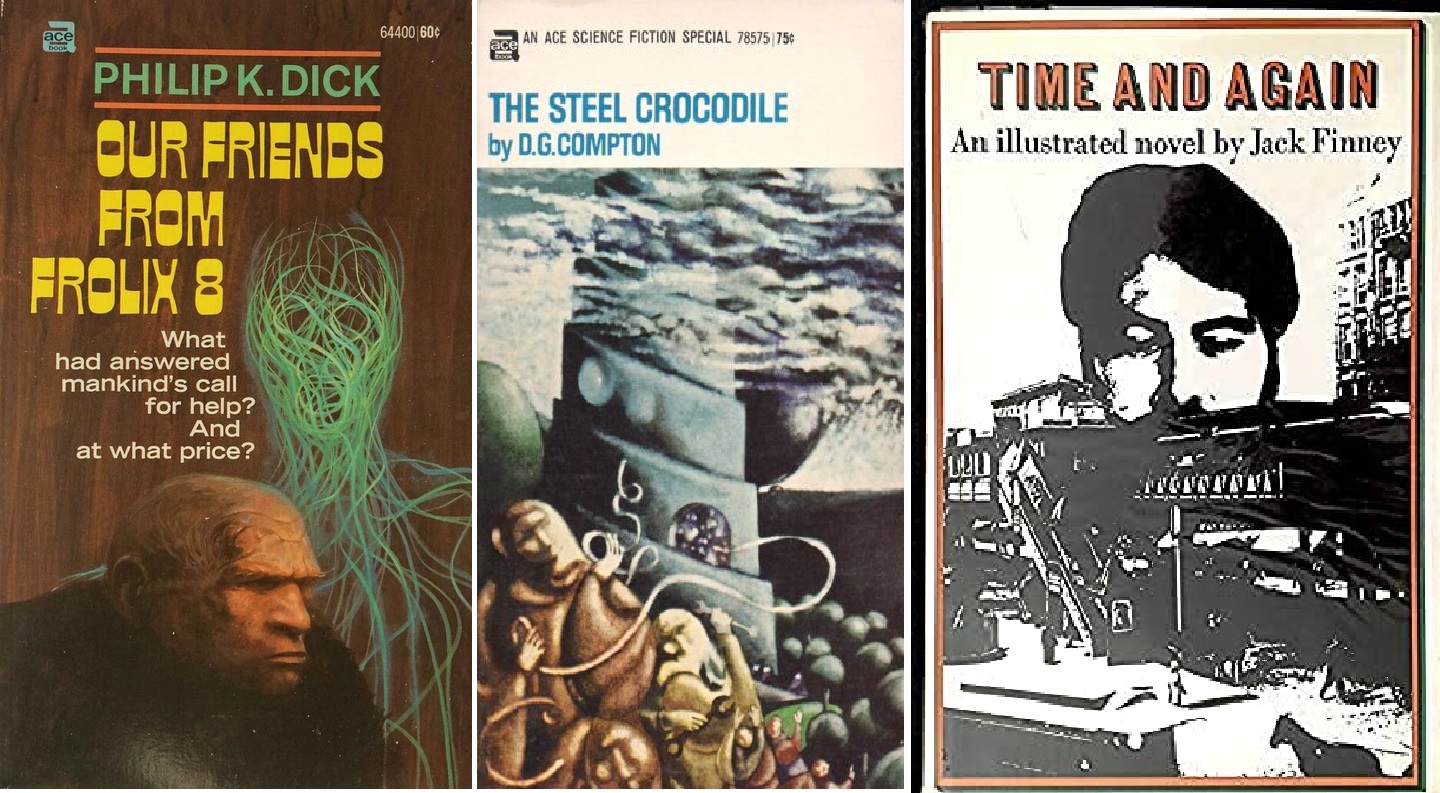

The January 1970 Amazing continues in its newly-established course—“ALL NEW STORIES Plus A Classic”—though it’s fronted in the all-too-long-established manner, with another capable enough but generic cover by Johnny Bruck, reprinted from a 1965 issue of Perry Rhodan. Editor White has acknowledged this practice and, I suspect, is looking to end it when circumstances and the publisher permit.

by Johnny Bruck

The usual complement of features are here, starting with a long editorial meditation about the Moon landing, reactions to it, the progress (or lack thereof) of technology generally, and a note of cogent pessimism about the future of the space program: we can do it, but will we? The book reviews continue long and feisty, with White slagging James Blish’s generally well-received Black Easter, concluding: “At best, then, Black Easter is not a novel, but only an extended parable. At worst, it is a tract. In either case, it pleads its point through the straw-man manipulations of its author in a fashion I consider to be dishonest to its readers.” The milder-mannered Richard Delap says that Avram Davidson’s The Island Under the Earth “isn’t a horrid book like some of the dredges of magazine juvenilia we’ve seen recently; it’s soundly adult and imaginative but just too uneven and incomplete to be a good one.” Damning with faint praise, or the opposite? New reviewer Dennis O’Neil, a comic book scripter and “long a friend of SF, and a one-time neighbor of Samuel Delany,” compliments Thomas M. Disch’s Camp Concentration: “Of all the adjectives which might be applied to Camp Concentration—‘artful,’ ‘brilliant,’ and ‘shocking’ come to mind—maybe the most appropriate is ‘heretical.’ ” He then reads the book in terms of Disch’s assumed religious background. “Catholicism is a hard habit to kick. James Joyce didn’t manage it, and neither does Tom Disch.”

The regular fanzine reviewer, John D. Berry, is on vacation, so White turns the column over to “Franklin Hudson Ford,” apparently a pseudonym of his own, for a long and praiseful review of Harry Warner’s fan history All Our Yesterdays. The letter column is even more contentious than the book reviews, with one correspondent addressing “My Dear Mr. Berry: You and your coterie of comic-stripped idiots” (etc. etc.). John J. Pierce, he of the “Second Foundation” and denunciations of the New Wave, explains that he really does have some taste: “If the romantic, expansive traditions of science fiction are to be saved, they will be saved by the Roger Zelaznys and the Ursula LeGuins, not by the Lin Carters or the Charles Nuetzels”—a point I had not realized was in contention. William Reynolds, an Associate Profession of “Bus. Ad.” at a Virginia community college, tries to correct White about the operation of the Model T Ford and provokes a response as spirited as it is mechanical. One Joseph Napolitano complains about “new wave stories”: These new wave writers “don’t want to work. Its [sic] not easy to come up with an idea for a story and they just don’t want to take the time and use what little brains they have to do this.” (Etc. etc.)

After all this amusing contention, it is unfortunate to have to report that the fiction contents of this issue are pretty lackluster.

A. Lincoln, Simulacrum (Part 2 of 2), by Philip K. Dick

I’m a great admirer of Philip K. Dick’s best work, and some of his less perfect productions as well. So it’s painful to report that A. Lincoln, Simulacrum, is a bust. It has its moments, but there aren’t enough of them and they don’t add up to much, even though the novel’s themes reflect some of Dick’s long-standing preoccupations.

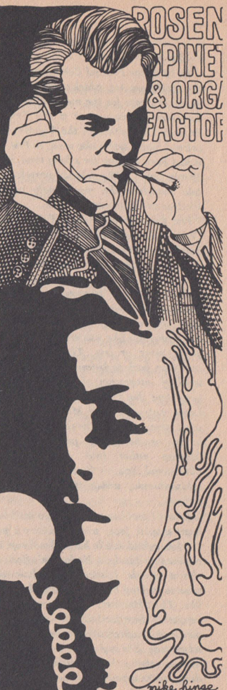

Protagonist Louis Rosen is partner in a firm that manufactures and sells spinet pianos and electric organs. But now his partner Maury is branching out into simulacra—android replicas of historical persons, designed by his daughter Pris. They’ve started with Edwin M. Stanton, President Lincoln’s Secretary of War. How? “. . . [W]e collected the entire body of data extant pertaining to Stanton and had it transcribed down at UCLA into instruction punch-tape to be fed to the ruling monad that serves the simulacrum as a brain.” Ohhh-kay.

More importantly, why? Because Maury thinks America is preoccupied, in this year of 1981, with the Civil War, and it will be good business to re-enact it with artificial people. Pris is now working on a Lincoln simulacrum.

by Michael Hinge

Staying over at Maury’s house, Louis meets Pris, recently released from the custody of the Federal Bureau of Mental Health, which provides free—and mandatory—treatment for people identified as mentally ill per the McHeston Act of 1975. Louis mentions that one in four Americans have served time in a Federal Mental Health Clinic. Pris was diagnosed as schizophrenic, and committed, in her third year of high school.

Louis asks her to stop her noisy activities because it’s late and he wants to go to sleep. She refuses, and says, “And don’t talk to me about going to bed or I’ll wreck your life. I’ll tell my father you propositioned me, and that’ll end Masa Associates and your career, and then you’ll wish you never saw an organ of any kind, electronic or not. So toddle on to bed, buddy, and be glad you don’t have worse troubles than not being able to sleep.” Louis thinks: “My god. . . . Beside her, the Stanton contraption is all warmth and friendliness.”

In a later encounter: “Why aren’t you married?” she asked.

“I don’t know.”

“Are you a homosexual?”

“No!”

“Did some girl you fell in love with find you too ugly?”

In addition to this finely honed nastiness, Pris is also capable of considerable depression and self-pity. After the Lincoln is completed:

“Oh, Louis—it’s all over.”

“What’s all over?”

“It’s alive. I can never touch it again. Now what’ll I do? I have no further purpose in life.”

“Christ,” I said.

“My life is empty—I might as well be dead. All I’ve done and thought has been the Lincoln.”

Louis is shaken by these encounters. He sees a psychiatrist and gives a paranoid account of events to date, threatening to kill Pris. Further: “I was not kidding when I told you I’m one of Pris’ simulacra. There used to be a Louis Rosen, but no more. Now there’s only me. And if anything happens to me, Pris and Maury have the instructional tapes to create another.” Later he reiterates, in a conversation with the Stanton: “I claim there is no Edwin M. Stanton or Louis Rosen any more. There was once, but they’re dead. We’re machines.” The Stanton acknowledges, “There may be some truth in that.”

And if you’ve missed the point about humans and simulacra, here it is from the other direction. The Stanton says he would have liked to see the World’s Fair. Louis says: “That touched me to the heart. Again I reexperienced my first impression of it: that in many ways it was more human—god help us!—than we were, than Pris or Maury or even me, Louis Rosen. Only my father stood above it in dignity.”

The characters get involved with Sam Barrows, a rich guy who is the talk of the nation, in hopes of a profitable business relationship. Barrows is selling real estate on the Moon and other extraterrestrial locations. He sensibly trashes Maury’s idea of Civil War re-enactment, but his proposal is hardly an improvement; he wants to create simulacra of ordinary folks to go live in his off-planet housing developments and make them seem homier to potential buyers. (Sounds very practical, right?)

Pris then takes up with Barrows and begins calling herself Pristine Womankind. Meanwhile, Louis is getting progressively crazier, propelled by his obsession with Pris, and eventually winds up committed to the Federal Bureau of Mental Health—and is glad. There are a few more events and revelations I won’t spoil.

So, what follows from this prolonged but foreshortened precis?

First, this is not a very good SF novel, because it doesn’t follow through on its SFnal premises and also doesn’t make a lot of sense in general. It starts with the premise that historical replicas can be convincingly manufactured, and can exercise volition and easily adapt to a world a century in their future. OK, show me. But Dick doesn’t. We actually see relatively little of the Stanton and the Lincoln over the course of the novel. Further, we’re told that these artificial people are variations on models developed by the government. For what? And where are they and what are they doing? There’s no clue about the effects of this rather monumental development, other than allowing an obscure piano company to tinker with it.

The novel’s envisioned future doesn’t add up either. We’re told the setting is the USA in 1981, but there is routine space travel and colonization of the Moon and planets. More mind-boggling, there is the Federal Bureau of Mental Health—created by statute in 1975!—under which the entire population must take mental health tests administered in schools, and those deemed mentally ill are committed to a mental health clinic. As already noted, a fourth of the population has been committed at some point. And what political or cultural crisis or revolution has not only countenanced such an authoritarian regime, but also come up with the money for such a gigantic system of confinement?

Dick also seems to have made up his own system of psychiatry. Louis is diagnosed with a mental disorder requiring commitment through the James Benjamin Proverb Test. While interpretation of proverbs is sometimes used in psychiatric diagnosis, I can’t find any indication that this Benjamin Test exists anywhere besides Dick’s imagination.

Louis is asked to interpret “A rolling stone gathers no moss.”

“ ‘Well, it means a person who’s always active and never pauses to reflect—’ No, that didn’t sound right. I tried again. ‘That means a man who is always active and keeps growing in mental and moral statute won’t grow stale.’ He was looking at me more intently, so I added by way of clarification, ‘I mean, a man who’s active and doesn’t let grass grow under his feet, he’ll get ahead in life.’

“Doctor Nisea said, ‘I see.’ And I knew that I had revealed, for the purposes of legal diagnosis, a schizophrenic thinking disorder.’”

Turns out the correct answer—which Louis says he really knew—is “A person who’s unstable will never acquire anything of value.” But if any of the other interpretations of this deeply ambiguous platitude—or acknowledgement of its ambiguity—proves one a schizophrenic, I guess I’d better turn myself in. (Cue soundtrack: “They’re Coming to Take Me Away.”)

The doctor goes on to explain that Louis has the “Magna Mater type of schizophrenia”:

“ ‘The primary form which ‘phrenia takes is the heliocentric form, the sun-worship form where the sun is deified, is seen in fact as the patient’s father. You have not experienced that. The heliocentric form is the most primitive and fits with the earliest known religion, solar worship, including the great heliocentric cult of the Roman Period, Mithraism. Also the earlier Persian solar cult, the worship of Mazda.’

“ ‘Yes,’ I said, nodding.

“ ‘Now, the Magna Mater, the form you have, was the great female deity cult of the Mediterranean at the time of the Mycenaean Civilization. Ishtar, Cybele, Attis, then later Athene herself . . . finally the Virgin Mary. What has happened to you is that your anima, that is, the embodiment of your unconscious, its archetype, has been projected outward, unto the cosmos, and there it is perceived and worshipped.’

“ ‘I see,’ I said.”

Now, nowhere is it written that an SF writer can’t invent future psychiatry, any more than future physics or sociology, or alternative history. But plopping this scheme down in the America of 12 years hence, without support or explanation of how we got there from here, is incongruous and implausible. And the nominal date of 1981 is not the issue. The novel is firmly set in the familiar USA of today or close to it, with androids, spaceships, and psychiatry based on ancient religions in effect stuck on with tape and thumb tacks.

Of course, absurdity and incongruity are far from rare in PKD’s work, but they generally appear in the context of madcap satire or grim lampoon (consider Dr. Smile, the robot psychiatrist-in-briefcase in The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, whose function is not to cure, but to drive the protagonist crazy so he can evade the draft). But that’s not what’s going on here. This novel, though it has its witty moments, presents overall as thoroughly sober and serious, assisted by Louis’s flat first-person narration.

So, if it’s not good SF, is it good anything else? Editor White said in the last issue, “It’s more of a novel of character than any previous Philip K. Dick novel, and in writing and scene construction it approaches the so-called ‘mainstream’ novel.” Pris is an appallingly memorable character, both for her conduct and for her effect on others, and her part of dialogue is finely honed. A novel that closely examined her and her effect on those around her might be quite impressive. But in a novel that starts out with android historical figures and ends up in a national coercive mental health system, with spaceships and moon colonies along the way, there’s too much distraction for Pris and her relationships to be adequately developed.

The bottom line is that the author has mixed up elements of SF and the “mainstream” novel without developing either satisfactorily or adequately integrating them.

In the last chapter, the author makes a conspicuous effort to bring the novel’s disparate elements together, and winds things up in the most quintessentially Dickian fashion imaginable. In fact, it all seems a little too pat. But wait. Remember editor White’s cryptic statement in last issue’s editorial that this serial was not cut, but was “slightly revised and expanded” for its appearance here? There’s a rumor that this last chapter was not actually written by Dick, but was added by White. True? No doubt we’ll find out . . . someday.

A readable failure. Two stars.

Moon Trash, by Ross Rocklynne

Ross Rocklynne (birth name Ross Louis Rocklin) started publishing SF in 1935 and became very prolific in the 1940s, placing more than 10 stories most years through 1946, many in the field leader Astounding Science Fiction, but most in assorted pulps. After that his production fell off, he disappeared from Astounding, and ceased publishing entirely from 1954 to 1968, when he reappeared with a burst of stories in Galaxy. He was a heavyweight by production, but seemingly a lightweight by lasting impact. Only five of his stories were picked up in the explosion of SF anthologies of the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, and to date he has published no books.

by Ralph Reese

Moon Trash is a contrived piece about young Tommy, who lives on the Moon with his cranky old stepfather Ben Fountain; his mother seems to be dead though it’s not explicit. Tommy has bought the official ideology of keeping the Moon spick and span, and Ben gets annoyed when Tommy picks up things that Ben has dropped along the way. Then Tommy finds a bit of trash that somebody dropped about a million years ago, and it leads them to a cave full of artifacts of an alien civilization, including precious gems.

Ben’s not going to tell anybody and is going to see how he can make money from this find, but in his greed he pulls a heavy statue over and it kills him. Tommy reports that Ben fell down a crater wall, returns the artifact Ben had taken to the cave, tells no one about it, and resolves he’s going to work and become a big shot on the Moon. The obvious subtext of the title is that even on the Moon there will be people who are down and out or close to it—people like Ben are the Moon trash, though young Tommy is a class act. Three stars, barely.

Merry Xmas, Post/Gute, by John Jakes

John Jakes had been contributing to Amazing and other SF magazines, mostly downmarket, since 1950, to little notice or acclaim until he devised his Conan imitation Brak the Barbarian for Fantastic. In his very short Merry Xmas, Post/Gute, an impoverished author tries to get the last remaining book publisher to read his manuscript, only to be told it is closing its book division as unprofitable. It’s as heavy-handed as it is lightweight. Two stars.

Questor, by Howard L. Myers

Howard L. Myers—better known by his very SFnal pseudonym, Verge Foray—contributes Questor, a semi-competent piece of yard goods of the sort that filled the back pages of the 1950s’ SF magazines. Protagonist Morgan is part of a raid brigade attacking Earth, without benefit of spaceships, which are passe in this far future. He’s a Komenan; Earth is dominated by the Armans; it's not clear why we should care. Morgan is special; his assignment is to pretend to be a casualty and fall to Earth; but he’s hit by a “zerburst lance” and both he and his transportation equipment are injured. He lands in a Rocky Mountain snowbank and emerges, after some recuperation, to find himself in a valley he can’t climb out of.

by Jeff Jones

But all is not lost. A talking mountain goat, named Ezzy, appears (intelligence and fingers engineered by long-ago humans), and offers to help him out. We learn just what Morgan is looking for on Earth—it’s called the Grail! Or, the goat says, “it can be called cornucopia, or Aladdin’s Lamp—or perhaps Pandora’s Box. . . . The only certain information is that it has vast power, and has been around a long time.” Morgan later adds, “We only know it appears to assure the survival and success of whatever society has it in its possession.” Can we say pure MacGuffin? And of course there is a wholly predictable revelation at the end involving the goat. Two stars for egregious contrivance.

The People of the Arrow, by P. Schuyler Miller

by Leo Morey

This month’s “Famous Amazing Classic” is P. Schuyler Miller’s The People of the Arrow, from the July 1935 Amazing, and it does not impress. Kor, the leader of a migrating prehistoric tribe (having recently dispatched his elderly predecessor), returns with a hunting party to discover that their camp has been attacked by ape-men (he can tell by their footprints). They have wreaked terrible carnage and have carried off the women they did not kill. So the hunting party pursues the ape-men and wreaks terrible carnage on them with their superior armament (see the title). Miller does make a credible attempt to suggest the workings of Kor’s mind and his appreciation of the changing landscape he traverses, but it’s all pretty badly overwritten and mainly notable as a large bucket of blood. Miller—now best known as book reviewer for Analog and its predecessor Astounding—did much better work later. Two stars.

The Columbus Problem: II, by Greg Benford and David Book

Last issue’s “Science in Science Fiction” article asked how difficult it would be to locate planets in a star system from a spaceship traveling much slower than the speed of light. This issue, they ask how difficult it would be from a spaceship traveling much faster—say, a tenth of light-speed. (The authors say flatly: “To the scientific community, . . . FTL is nonsense.”) Then they take a quick turn for several pages of exposition about how an affordable and workable sub-light spaceship could be designed. The Goldilocks option, they suggest, is that proposed by one Robert Bussard: a ramscoop (magnetic, since it would need about a 40-mile radius) to collect all the loose gas and dust floating around in space and channel it into a fusion reactor.

Sounds great! Once you solve a few technical problems, that is. And then finding planets is a breeze. They’ll all be in the same plane, as in our solar system—it’s all in the angular momentum. Approach perpendicular to that plane, and Bob’s your uncle. Then a fly-by can reveal basics of habitability—gravity, temperature, what’s in the atmosphere—but looking for existing life and habitability for terrestrials will require landing, preferably by remote probes of several degrees of capability.

This one is denser than its predecessor, but as before, clear, clearly well-informed, and aimed at the core interests of, probably, most SF readers. Four stars.

Summing Up

So, assuming one agrees with me about the serial, there’s not much of a showing here for this resurrected magazine, though it’s far too early to be making any broad judgments. Promised for next issue are (the good news) a serial by editor White, who has demonstrated his capabilities as a writer, and (the bad news) a story by Christopher Anvil! No doubt a Campbell reject. Let’s hope the promising overcomes the ominous.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

by John Boston

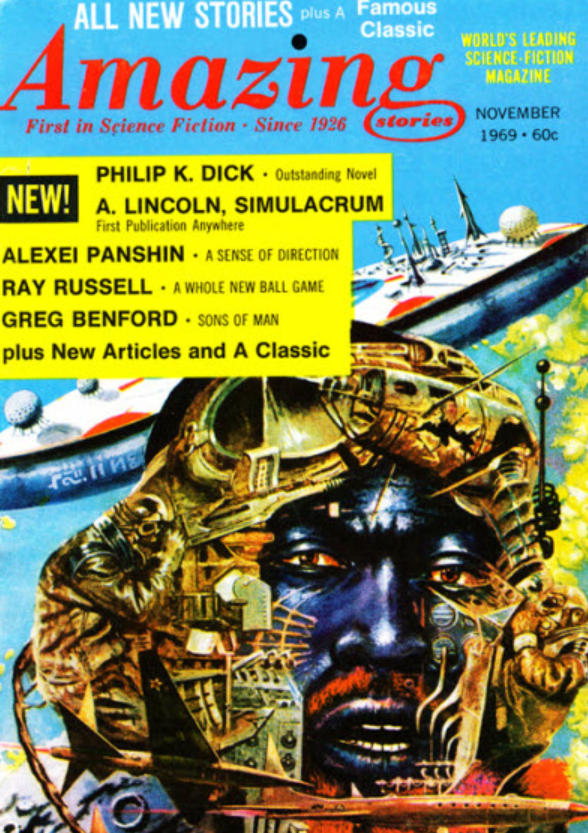

. . . Amazing has become a normal science fiction magazine. (Stop snickering.) It’s been moving in that direction, but this November issue’s editorial says: “Beginning this issue, our old policy of reprints has been thrown out the window. . . . We will be publishing one, and only one classic story in each issue, and it will be a bonus to the fully new contents of the magazine.” Or, as the cover blurb puts it, “ALL NEW STORIES plus a Famous Classic.”

by Johnny Bruck

That phrase may seem oxymoronic, but here’s how editor White figures it: the magazine, with its new, smaller typefaces allowing more wordage, now contains about 70,000 words of new material, plus another 15,000 words, making a total per issue greater than any of the other SF magazines and allowing him to call the remaining reprints bonuses. Thus the booster’s reach exceeds the mathematician’s grasp, but I’m not complaining.

Promotion aside, congratulations to White for finally prying publisher Sol Cohen loose from his prolonged insistence on filling as much as half the magazine with reprints of (euphemistically) uneven quality. White says he “cannot truly say it was a result of my actions alone”—presumably meaning Cohen had been softened up by the complaints of his predecessors—but good for him for finally getting it done.

So what we have here are one quite long serial installment, a novelet, and two short stories, plus a reprinted short story from 1942, all new, as well as the usual complement of features. As promised last month, there is a science article by Greg Benford and David Book, and as then implied, Dr. Leon E. Stover is conspicuous by his absence, and not missed.

A book review column, shorter than usual but just as vehement, features editor White’s praise of Lee Hoffman’s The Caves of Karst and a new reviewer, Richard Delap, whaling on Bug Jack Barron: “Science fiction’s answer to Valley of the Dolls has now made the scene with all the pseudo-values of its mainstream counterpart unrevised and intact in a transposition to pseudo-sf.” Delap also doesn’t care much for the new collection of old stories The Far-Out Worlds of A.E. van Vogt, but this disappointment is expressed more in sorrow than in gusto. These two reviews are reprinted from a fanzine, but Delap will be contributing regularly to this column going forward.

The fanzine reviews and letter column fill out the issue. In the letter column, White notes that James Blish has moved to England and his book reviews will be less frequent. Other highlights of the letter column include Joe L. Hensley complaining in kind about the misspelling of his name on last issue’s cover, Bob Tucker reviving his 36-year-old beef about staples, to White’s consternation, and both White and John D. Berry, the fanzine reviewer, weighing in on the purpose of that column in response to a complaining reader. White takes issue with a reader who thinks the use of “sci-fi” is only a minor problem, and announces to another reader that he has dropped the movie reviews for the present. He also notes that he continues to write stories but his agent insists on sending them to Playboy—where, I note, nothing by White seems yet to have appeared.

Oh, the cover. I almost forgot. It’s the good cover by Johnny Bruck that we’ve been waiting for—not especially attractive, but very interesting. Foregrounded is an African-looking face peering out from what at first looks like the fur-lined hood of one of the Inuit or other far-North American peoples, but on closer examination is a collage of partial images of pieces of equipment and (I think) living things. It’s a surreal picture that, unusually, doesn’t look like imitation Richard Powers. Provenance is the German Perry Rhodan #250, from 1966.

On the contents page, Greg Benford’s story Sons of Man is listed as “The story behind the cover.” White said last issue that he doesn’t have control over the covers, but he’s been able to commission stories, including Benford’s, to be written around the pre-purchased covers. So I guess Sons of Man is actually the story in front of the cover. Inside, the story is illustrated by none other than editor White—his first professionally published art. It’s adequate, but he shouldn’t quit his day job. In other interior illustration news, Mike Hinge has done small illustrations for the headings of the editorial, book reviews, and other departments.

A. Lincoln, Simulacrum (Part 1 of 2), by Philip K. Dick

The biggest news in this issue is Philip K. Dick’s serial, A. Lincoln, Simulacrum. Per my practice, I won’t read and rate this until both installments are available, but there’s plenty of talk about the novel here. White’s editorial says without elaboration that it is totally uncut—in fact, it’s “slightly revised and expanded” for its appearance here.

by Mike Hinge

White does leave us with a bizarre anecdote. Several years ago, he showed Dick a photo of himself looking rather like Dick (both with full beards and dark-rimmed glasses). Dick asked for a copy, since his agent was after him to provide a photo for a British edition of The Man in the High Castle. So Dick sent the photo of White—and it appeared on the book. White says: “So here’s a chance to say, ‘Thanks, Phil,’ for the chance to associate myself, albeit deceitfully, with one of his best books.”

About the novel, White says:

“. . . Phil told me, ‘I put a lot of myself into this one—I really sweated into it.’ It’s more of a novel of character than any previous Philip K. Dick novel, and in writing and scene construction it approaches the so-called ‘mainstream’ novel. It is also something of a ‘root’ novel, planting as it does in 1981 many of the themes and constructs which pop up in later books of his loose-limned future history. And it is the first and only Philip K. Dick novel to be told in first person by its protagonist.”

Sons of Man, by Greg Benford

by Ted White

Greg Benford’s Sons of Man is a well crafted story using the familiar device of telling two unrelated stories in parallel, gradually revealing that they are not so unrelated after all. In one, Livingstone, who has moved to the northwestern wilderness to get away from civilization, finds a man named King collapsed in the snow near his cabin with severe burn injuries of no obvious origin, then sees a face peering into his window, and later, bare footprints two feet long. King’s been Sasquatch hunting and they seem to be hunting him back.

Meanwhile, on the Moon, Terry Wilk is trying to make sense of the records of an ancient spacecraft that crashed after visiting Earth early in human prehistory. Members of the New Sons of God cult are looking over his shoulder to make sure he doesn’t find out anything heretical. The story reads like it might develop into a series but stands on its own. The style seems a little awkward at the beginning, as if it’s something Benford started earlier in his career and came back to later, but overall, it’s very readable, cleverly assembled, and generally enjoyable. Four stars.

A Sense of Direction, by Alexei Panshin

Alexei Panshin’s short story A Sense of Direction is set in the same universe of “the Ships” as his Nebula-winning Rite of Passage. The interstellar Ships lord it over the people of the colonies that they established. Arpad, whose father married into a planetary culture and left (was left by) his Ship, was reclaimed for the Ship when his father died. He’s miserable in its unfamiliar culture, and makes a break for it during a landing on another planet. But the folkways there are so bizarre and repellent that he quickly changes his mind and sneaks back. So, like most of Panshin’s work, it’s Heinleinian: The (Young) Man Who Learned Better, capably done but just a bit too schematic and pat. Three stars.

A Whole New Ballgame, by Ray Russell

Ray Russell contributes A Whole New Ballgame, a compressed soliloquy on a theme previously aired by Larry Niven (in The Jigsaw Man), with a first-person semi-literate narrator. It’s just about perfect in its small compass and inexorable logic. Four miniature stars.

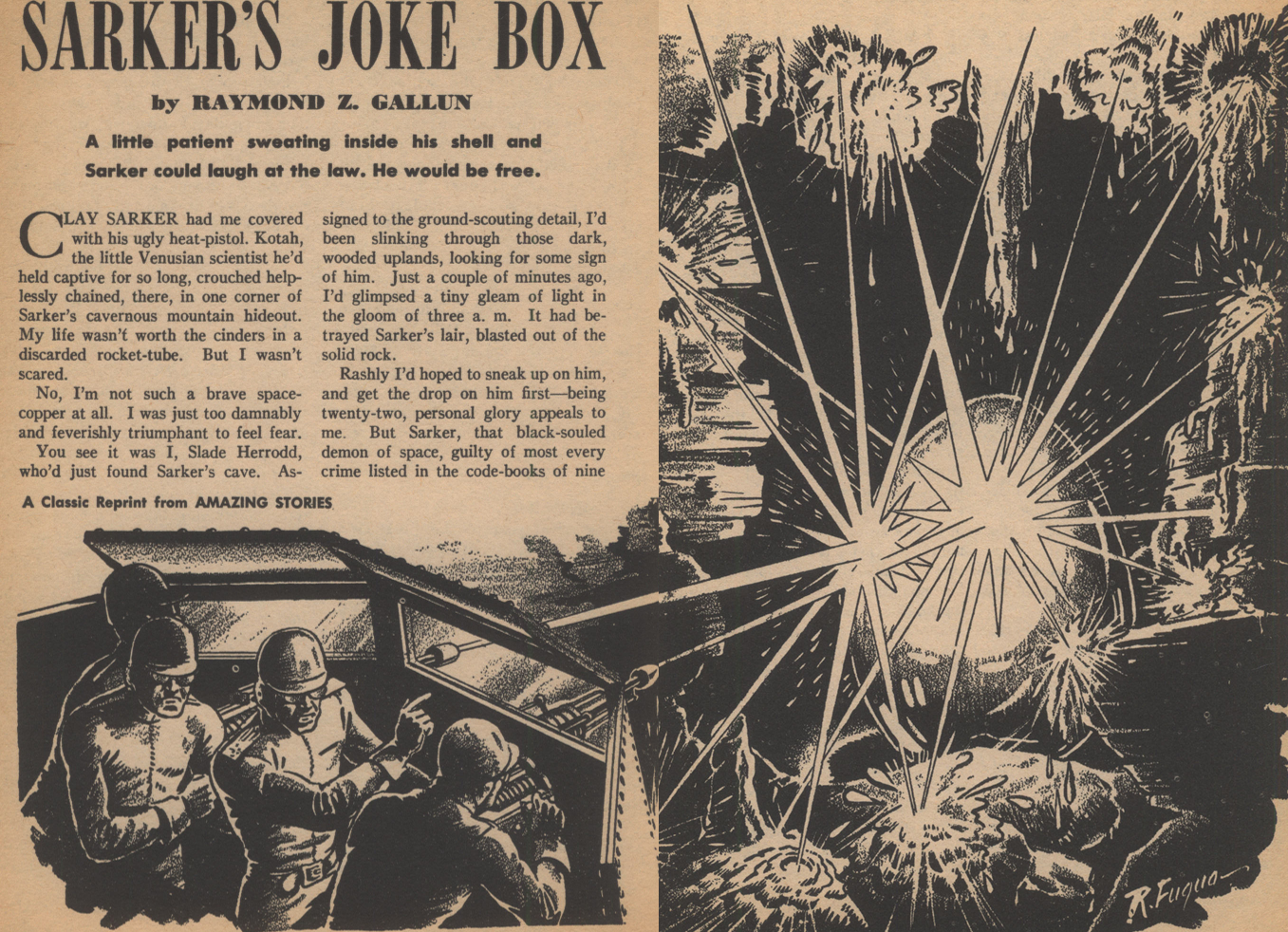

Sarker’s Joke Box, by Raymond Z. Gallun

The “Famous Classic” this month is Sarker’s Joke Box, by Raymond Z. Gallun, from the March 1942 Amazing. It’s yet another testament to the corrupting effects of Ray Palmer’s editorship. It begins: “Clay Sarker had me covered with his ugly heat-pistol. Kotah, the little Venusian scientist he’d held captive for so long, crouched helplessly chained, there, in one corner of Sarker’s cavernous mountain hideout. My life wasn’t worth the cinders in a discarded rocket-tube.” “Gimme bang-bang” wins out again! Pull out your copy of the June 1938 Astounding Science-Fiction, or the anthology Adventures in Time and Space, and compare Gallun’s much classier Seeds of the Dusk to this one.

by Robert Fuqua

But the story is not a total loss. The narrator is a cop, and he and his buddies have rousted Sarker out of his last stronghold in the Asteroid Belt. Now he’s trapped in a cave on Earth while the other cops are closing in. But Sarker—“that black-souled demon of space”—turns his heat-pistol on Kotah and then on his own apparatus that fills the cave, which blows up quite satisfactorily, then enters a metal cylinder and closes and seals it behind him. When the main body of cops arrive, they try to penetrate it, but—it’s neutronium! They can’t scratch it. And to compound matters, Sarker’s lawyer appears and announces that since they’ve declared Sarker to be in custody, they’ve got to try him within 60 days or he goes free. So the cops redouble their efforts to get through the neutronium. At this point, the story turns into a scientific puzzle without (much) further resort to hokey melodrama. It’s perfectly readable and commendably short. Three stars.

The Columbus Problem, by Greg Benford and David Book

Greg Benford’s second appearance in the issue is the first “Science in Science Fiction” article, done with David Book. It’s called The Columbus Problem and it starts out with a quotation from a Poul Anderson novel about a spaceship arriving at a new star system: “The instruments peered and murmured, and clicked forth a picture of the system. Eight worlds were detected.” Benford and Book then explain just how difficult and time-consuming it would actually be to detect the planets of an unfamiliar star system upon arrival at it, with our present technology or likely enhancements of it. They do a fine job of plain English explanation without becoming tedious. It beats hell out of Frank Tinsley’s earlier science articles for Amazing and edges Ben Bova’s. Four stars.

Summing Up

So, deferring judgment on the serial, here’s a lively issue of which much is quite good and nothing is a chore to read. Amazing!

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

by Gideon Marcus

Government by the Many

Every four years, Americans head to the polls to vote for who they want to lead the Free World. At least, that's what they think they're doing. What really happens is your vote determines if your choice for President wins your state. And then, representatives of the states, the so-called "Electoral College", announce who they've been empowered to choose. Technically, these representatives are not bound to uphold the will of the voter; in practice, bucking the election results has been for protest rather than consequence.

This means that the swingier the state and the bigger the state, the more attention it will get. For instance, California, somewhat evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans, and currently the most populous state in the Union, is more important to a candidate than, say, a reliable and sparsely settled state like Arizona.

No more? This week, the House passed a proposed amendment to the Constitution that would make Presidents directly electable. This would mark the first major change to the system since 1803.

It looks like half the Senate is in favor, but it will take two thirds of that chamber plus three quarters of the states for the measure to go through. Opposing such reform are representatives of small states and rural areas, as they wish to retain their outsized impact on the process. With the rapid rate of urbanization, particularly on the coasts, this proposed amendment threatens to wipe out the electoral relevance of most of the central region of our country, from the Rockies to the Mississippi.

But that's precisely why the time for such an amendment has come, its advocates propose. People vote—not acres.

The bill faces an uphill battle, but it's an idea whose time has probably come.

Magazine by the Few

by Ronald Walotsky

Continue reading [September 22, 1969] Unsmoothed curves (October 1969 Fantasy and Science Fiction)

by Jason Sacks

Welcome to Seattle, and let me tell you, June 1969 is a busy month here in the often quiet Pacific Northwest. We have a baseball team! And we may be losing a relic of our past while fighting about the present and rocking our own giant music festival… well, at least, we will be rocking a field out in the suburbs!

And I also wandered into the ineffable mind of my favorite author, Philip K. Dick, and found I had journeyed to places I scarcely could have imagined.

We live in revolutionary times, times which are painfully uncertain and terrifying. In our era of political assassinations, cities on fire, images of Vietnam on TV every night, and endless sports expansion, many of us find ourselves craving the pleasures and traditions of the past in order to help us have some small ground under our feet, some small element of history to cling onto.

But that need for tradition runs solidly into the endless American drive for progress. And we are seeing that collision of progress with tradition even here in our often quiet city.

If you’ve ever visited Seattle, you’ve probably stopped to visit our Pike Place Market, a farmers market on the hilly edge of the Seattle waterfront. The Market has been around since the dawn of the 20th century, but it may not live to see the 21st century – or even most of the 1970s. See, commercial interests have come for the quaint old market and its prime real estate, aiming to convert that area into fancy hotels and expensive housing. This has triggered a pitched battle and a bit of existential turmoil.

Like New York with that neighborhood-destroying Robert Moses, many Seattle residents find ourselves fighting to preserve our landmarks against the machinations of moneyed corporate interests. And like New York with city advocate Jane Jacobs, we have our own leader of the cause. Victor Steinbrueck is a 57-year-old Seattle architect and University of Washington faculty member who has led the charge against the change

As Steinbrueck discusses in a recent issue of Seattle weekly Helix:

600 residents will be relocated in places mostly incompatible to their way of life, producing problems for themselves and others. Approximately 1400 workers will have their jobs placed in jeopardy trough relocation and termination of businesses. 233 businesses will be relocated or forced to close because of the disruption of the low cost market… the massive disruption to benefit a few is neither wise nor morally right.

Steinbrueck proposes several ideas for changes to the Market, all of which are devoted to keeping its unique character for generations to come. More than 53,000 people have already signed a petition to support his organization, Friends of the Market.

This struggle is existential for many of us who have felt buffeted around by the winds of change these days. We are hoping some of our favorite places survive the relentless, unforgiving march of progress, and Pike Place is one of those favorite places.

We can only hope and pray that Steinbrueck’s efforts will bear the same fruits Ms. Jacobs achieved in New York. I love the Market for many reasons, and hope I can continue to stop there for fruit, fish and fresh meals whenever I possibly can.

On a cheerier note, there’s been a lot of buzz around town discussing the upcoming Seattle Pop Festival, which will be held in the sleepy Eastside suburb of Woodinville. Many Seattle music fans will be driving over the Evergreen Point Floating Bridge to see such amazing bands as The Doors, Chuck Berry, Albert Collins, the Guess Who, Ike & Tina Turner and the much hyped “New Yardbirds”, Led Zeppelin. (there’s a nice mix of traditional and new acts!)

It’s going to be an expensive event at $6 per day or $15 for the whole three days, and there have been rumors that drug peddlers in the University District have been more aggressive than ever before selling their merchandise in order to afford tickets. It would be groovy if our event was like that upcoming Woodstock event in New York, but I predict that event will be a bit of a bomb. I just don't think there are enough people here who will be excited to see a boring band like The Doors.

Sadly, we’ve all been looking forward to a major civic event which has definitely become a bomb. After many years of dreaming and a mere few months of planning, the Seattle Pilots debuted this April as the latest team in the American League. They’re now our second Seattle pro sports team, after the SuperSonics of the NBA, and while Washington Huskies football will always be the big sport in Sea-town, and the hydros as number two, my friends and family and I all had high hopes for the expansion Pilots.

Unfortunately, everything about the Pilots has shown that the Emerald City isn’t like Oz. Our team’s ballpark is strictly minor league, the players are strictly second-stringers, and even their uniforms are an absurd joke.

First of all the ballpark: the Pilots home field is called Sicks’ Stadium, and seldom has a name been more appropriate. The field has been in use since before WWII hosting games of the Seattle Rainiers and Seattle Angels of the minor league Pacific Coast League, and the place feels like a minor league relic. The walls often feel like they’re falling down, the bleachers are rickety, and you probably heard the (completely true) story that the stadium was still under construction on Opening Day. Worse than that, the bathrooms often overflow during games, which is just nauseating. And on top of all that, we have higher ticket prices than the other expansion teams this year. No wonder we rarely have crowds which even approach 20,000 fans.

The boys in pastel blue are resolutely in last place in the new American League West, without much hope of avoiding the curse of 100 losses this year. Aside from a couple of decent players, like Yankee castoff Jim Bouton, this year’s team might be long-forgotten in a few years…

If not, that is, for the dreadful uniforms the players are forced to wear. Embracing the idea of a “pilot” way too far, the team’s owners created a cap like no other in baseball, with a captain’s stripe and “scrabmbled eggs” on the bill, which just looks hideous. But hey they are just as bad as the weird powdered-blue uniforms with four stripes on the sleeves, which just look odd.

Just three months into the season, there are already rumors the Pilots may be a one-year wonder, leaving my beloved city for parts unknown. That would be a shame on one hand, but a relief on another. If we’re going to sail into the big leagues, I would hope it would be when steered by a fine mariner instead of a minor-league pilot. Perhaps we will keep the team, and perhaps the Pilots will be able to move into a rumored domed stadium sometime by the middle of the next decade. And hey, they could start winning, right? Just wait’ll next year, as they say.

If you’ve ready any of the writing I’ve done for this zine, you’re probably aware I’m perhaps the biggest fan of Philip K. Dick on this staff. I’ve raved about his Dr. Bloodmoney, enthused about his transcendent Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, and – just last month – waxed poetic about his sublime Ubik.

Mr. Dick has been remarkably prolific over the last few years and has been on a magical roll, success following success. This month sees his latest paperback original hit in a B. Daltons or Woolworths near you. And while brilliant as ever, Galactic Pot Healer is a decidedly different book than the ones I just mentioned.

The lead character of Pot Healer is a miserable middle aged man with few job prospects living a blandly dystopian near-future – hmm, well, maybe this book not too different from other PKD novels. But stay with me for a minute because this book goes in unexpected directions.

Joe Fernwright is a brilliant artisan, a man with the unique skills to repair antiquities from the pre-WWIII era in such a way that they look as good as they did before the War. The term for such a man is pot-healer. Joe’s been a pot-healer all his life. In fact Joe follows in the footsteps of his father, who was a great pot-healer in his time.

The problem, in a future North American megalopolis, is that there’s no more pot-healing work for Joe. All the pots have been fixed and, in this post-apocalyptic world, there are no more porcelain pots being manufactured. In fact, there’s scarcely any work for anybody in this massive, overpopulated world. Instead, Joe shows up to work each day, sits at his desk, and calls up colleagues in Russia and England on his office phone not to work – there is no actual work for anyone in this future world to do – but instead to play pointless but clever word games just to make the long day feel slightly less meaningless.

It's a crushing, desperately lonely experience, bereft of any redeeming elements which would make life worth living. Joe has no family and really no friends, despite – or maybe because of – the fact that the megalopolis is so overcrowded. Even Joe’s small savings of a handful of actual metal coins, which he hides in his toilet back, are not able to gain him more than a few moments satisfaction in his life.

Until, that is, Joe starts receiving strange messages, which he soon realizes come from a strange being from another planet. The Glimmung summons Joe and a slew of other artifact hunters from across the galaxy – all suicidal dead-enders, all desperate for a chance to find fulfillment in their lives – to a remote obscure place called Plowman’s Planet where they can possibly achieve something which justifies their continued existence.

And though Joe finds some kind of love with an alien girl named Mali, ultimately Joe is unable to find peace with himself, leading to one of the bleakest, most powerful and satirical endings in all of Dick.

Galactic Pot Healer is one of PKD’s most downbeat and philosophical works. While Ubik thrills due to its endless tumble of ideas, Pot Healer is mostly about one idea, an idea central to Dick’s fiction: the feeling of deep, existential doubt and lack of fulfillment. Joe Fernwright is on a quest to truly find the true center of his being. In an amazing sequence I’ll let you discover yourself, Joe actually does find himself but finds himself desiccated, like the raw husk of an insect. He’s a man stripped raw, a man whose encounter with himself and with God leaves him frozen in his own mind, like a spider who spun his web in a tin can and starves to death waiting for a fly to hit his web.

Joe is a loser, but really what choice does he have? How can he actually change his life when every possible opportunity to do so is stripped away from him? What happens when great skills are lost, self-delusion is stripped away, and the stark reality is that everything is as dust?

This is all very emotionally exhausting stuff, for Joe and for the reader.

And that’s the difference between Galactic Pot Healer and Dick’s other recent novels. Characters like Robert Childan in The Man in the High Castle or Rick Deckard in Do Androids Dream or Palmer Eldritch in the book that bears his name are men of action, men who at least try to change their lives. Even boys like Manfred Steiner in Martian Time-Slip or the homonucleus in Dr Bloodmoney take actions to remake the world in their images.

But Joe Fernwright is the ultimate PKD character pushed to the edge, the ultimate man who is powerless before his own pathetic weakness.

Thus I found it hard to read about him, even while sympathizing with his pain and angst.

This is minor Dick, to be sure, but still an essential part of his catalog.

3.5 stars.

by Victoria Lucas

!NEWS BULLETIN!

Since those of you reading this might not be familiar with events in Berkeley, California, I thought I should report here the death of James Rector, a 25-year-old man shot by a sheriff deputy while on a roof watching the protest against the destruction of community improvements to a vacant lot belonging to the University of California, otherwise known as "People's Park."

Shot on May 15, he died on the 19th after several surgical attempts to repair vital abdominal organs damaged by the load of buckshot. A similar volley blinded another man, Alan Blanchard, on the same roof on the same day. If you have an urge to climb onto a roof to view a protest, suppress it. Law enforcement authorities do not recognize buckshot as lethal and are allergic to perceived threats from above. (I am quite opinionated about events like this. You may wish to seek other reports to obtain other views of the same events.) Below is a poem printed as a flyer, circulating on the streets now.

Michael McClure, "For James Rector"

We now return you to your regularly scheduled article

Cover of Ubik by Philip K. Dick

A Marathon Start

Beginning to read Philip K. Dick’s new book Ubik (1969, Doubleday) is like starting a marathon in the middle. Seeing other runners rushing by, you try to keep up, faster and faster, fearing to trip up. Not only does the book start in the middle of a crisis in what appears to be an important US company, but it also has a vocabulary full of made up words of which the meaning can only be inferred: “psis,” “teeps,” “bichannel circuits”; and the dead (if their relatives can afford it) are kept in “moratoriums” instead of crematoria or cemetaries. How can you keep up with things you can’t understand in a future you can only glimpse as felt by unfamiliar characters?

Author Philip K. Dick

Wondering if all Dick’s books are like this, I picked up library copies of his Eye in the Sky and The Cosmic Puppets (both 1957). The latter begins with a quiet, bucolic scene of children playing beside a porch. No rush. The former begins with an accident that causes injury, involving something called a “bevatron” and a “proton beam deflector.” No rush even there. For the most part, the vocabulary is ordinary in at least the beginning of these two. A little research turns up the fact that Dick first used the word “teep” (for telepath), for instance, in his story “The Hood Maker,” said to have been written in 1953, published in 1955, a year in which he used the same invented abbreviation in Solar Lottery.

Why is Ubik so different from other s-f books, even his own? Well, I had to persist to find out, and maybe you will too. I bet you’ll never guess where I found this book. I did not buy it. I found myself in a hand made hippie pad in the woods, dropped off by my husband Mel while he and one of the owners of the place went off to (I think) get wood for the winter. The other owner left with them or for some other errand, and I was alone in their kerosene-smelling dwelling, without anything to do. Wandering upstairs, I found bedding and pillows, and this book.

Not the actual house, but close

Since I hadn’t finished it by the time they returned, I borrowed it. This was the first really “science-fictiony” book I ever read. (I don’t count Flowers for Algernon, which I reviewed here on January 28, 1966, because that book has no assumptions out of the ordinary save one: that an experimental drug exists that can increase intelligence—no rocket ships, no bug-eyed monsters, no “vidphones.”)

Maybe Science Fiction Is Experimental Writing?

Anyway, persisting, I find myself in a future in which all the paranormal phenomena we humans have imagined are real and the foundation of industrial espionage and security, and the dead have a “half-life,” their brains wired into "consultation rooms" as their frozen bodies stand in caskets in a “moratorium," as above. The head of Runciter Associates, the company in crisis as above, must consult his dead wife Ella about the crisis. The “half-life” phenomenon, it is stated, “was real and it had made theologians out of” everyone. The citizens of this future are understandably prone to panic, to anxiety, to uncertainty.

Epigraphs for each chapter appear to be advertising for Ubik, which is variously represented as a “silent, electric” vehicle, a beer, a type of coffee, a salad dressing, a plastic wrap, etc. What is Ubik and where does it come from? No one knows. (Read the last epigraph in which it reveals its own nature to the extent it can.) Soon Runciter’s employees run into Pat, an “anti-precog.” It seems that she is an unusual practitioner of anti-precog[nition] in that she neither time-travels nor appears to do anything at all. But she changes the present and future by changing the past, leaving the affected people with little but (only sometimes) a trace memory of any previous present they have just experienced. Is all that strange enough for you? Wait! There's more.

There's Jory, dead at 15 years of age, who is on the wrong side of the struggle in the book between light, intelligence, and kindness, and greed, ignorance, and darkness. Keep an eye on him. His parents pay to keep his casket in the same areas as other "half-lifers," although his strong "hetero-psychic infusion" is clearly disturbing Ella Runciter and others.

Science-fiction satire?

Also keep in mind that in the previous year Kurt Vonnegut Jr.’s book God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater was published with a helmeted pig riding a unicycle on the cover and has been described as satire. Satire is seldom funny-ha-ha, but it is often funny. This book is occasionally funny-ha-ha, especially in the ridiculous clothing that appears to be popular in this dystopian future (1992).

For instance take this passage, in which an important space mogul enters wearing ”fuscia pedal-pushers, pink yakfur slippers, a snakeskin sleeveless blouse, and a ribbon in his waist-length dyed white hair.” OK, maybe that isn’t so far from what you might see now on Haight Street. But if this book were made into a movie, retaining Dick’s careful costuming would ensure it would be laughed off the screen.

The Cryonics Connections

Robert Ettinger in World War II uniform

Also notice that in 1967 the first person had been frozen, Professor James Bedford, preceded in 1962 by Robert Ettinger's book The Prospect of Immortality, in which he introduces the idea of cryonic suspension. Attempted cryopreservation of human beings was a real thing from then on. Which is part of what suggests that this book is satire as well as science fiction. And compare the plot of this book with that of Robert A. Heinlein's A Door into Summer, serialized in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction in October, November, and December of 1956 (published as a book a year later). In Heinlein's book a company executive is outmaneuvered and winds up in "cold sleep," waking up in the year 2000.

Mum's the Word

But anything more I write about the plot beyond what I’ve already written could well give away the plot. I can give you this hint, though, asked by the above-mentioned anti-precog (Pat) after most of the characters have experienced a bomb blast on Earth's moon: “Are we dead, or aren’t we?” And this one: the book makes it clear that human beings are so constituted that we can only know what our brains tell us (and, by the way, who is "us"?), which interpret what our senses (or in this book also our extra senses) send to it.

Oh, and one more thing. Oddly enough the last sentence in the book does not give anything away: "This was just the beginning." In any case I give it 5 stars out of 5 and recommend that you at least peek into it and see if it makes you crazy.

And Now for Something Completely Different

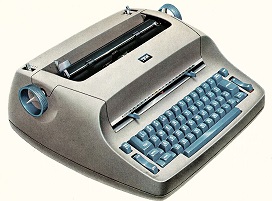

I'm going to tell you the truth about why my husband Mel and I spend so much time commuting between Humboldt County and San Francisco/Berkeley. It's The Book.

Good thing I've got a Selectric

The Book is dominating my life right now. I've spent many nights, holidays, any days I'm not working as a temp for Humboldt County, transcribing and writing as well as interviewing. For perhaps a year now I have been working with John Jefferson Poland, Jr., otherwise known (by his preference) as "F**k" Poland (or "Jeff"). After founding a sexual freedom "league" in New York City, he moved to Berkeley and founded similar groups there and in San Francisco, but insisting that a woman take up the cause and run the San Francisco group.

He wanted to produce a book on women in the sexual freedom movement–every variety from those who were brought all unwary to an SFL ("Sexual Freedom League") meeting or party to those who were/are leaders and spokeswomen for the cause.

I had done both interviewing and transcribing (the latter for a living), so it was mainly a matter of pointing me in the right direction and saying something like "go to it!" Jeff has been present at some of the interviews, in some cases commanded to be quiet so the women could speak for themselves.

"Meetings" are informational affairs in which leaders of the movement talk about the politics behind the parties and how they are conducted. "Parties" are what might be called orgies, with cheap red wine, a raised thermostat, and mattresses almost covering the floor of a Berkeley house. No man or men who seek entry without female companion(s) are admitted. It's heterosexual couples or single women only allowed. (Gays are excluded because two men could couple up and then only reveal themselves as straight predators of women when they are inside in the semi-dark and difficult to roust.)

And then there's me with my tape recorder, microphone, notebook, and voice, talking with women, making dates for interviews elsewhere and elsewhen. Real names are not used, except for one leader of the movement, Ina Saslow, who was arrested with Jeff during a nude demonstration on a public beach, then jailed, has her own chapter in her own words.

Empty theater, full stage

One night in San Francisco recently there was a party in an empty auditorium. The only celebrity attending was Paul Krassner, and he must have come with a woman, given the rules. Did he come with me? I'm so tired and busy right now I can't pull up the full memory. I mainly recollect standing with him behind a phalanx of mostly empty seats and watching the stage, on which were at least a dozen writhing couples. We agreed that it was an extraordinary sight. Oddly, I do not remember specifically whether he or I was wearing a full set of clothes at the time, but I think we were.

The Book is still in process. I will report progress when there is any, if desired. By the way, the book bears Jeff's name and my pseudonym as authors and is due to be published by The Olympia Press, Inc. (New York). Initial plans are to publish a hardback book with pictures of both authors/editors. Who wants to review my book when it comes out?

Ubik – A Second View

by Jason Sacks

Our dear editor has asked me to tack on a small response to Vicki’s review of Ubik, because I’m a huge fan of Mr. Dick’s work. I’ve read nearly everything he has written, and I feel that Martian Time-Slip, Dr. Bloodmoney and especially Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? are some of the finest science fiction novels of the '60s thus far.

On display in Ubik are all the elements which make Dick's work so transcendent and meaningful for me. We get miserable lead characters and subjective takes on reality; we get petulant children and time shifts and a weird, uncanny type of emotional resonance which only PKD can deliver.

I’m not going to dwell on the plot here, partially because my brilliant colleague has already done a great job summarizing this singular novel. And I’m also not going to dwell on plot because, well, this book has a plot, yeah it has a plot, but Ubik also has many plots, or no plots, or subtle plots, or infinitely recursive plots, or just some plotting that’s very particularly Phil Dick.

Am I making sense? I don't think I’m making sense….

And my lack of real coherence at this point is kind of appropriate, too. Because, like so many of Dick’s novels, Ubik has an incredible density of story; he presents layers and layers of events which build character and environment and plot and perceptions and problems, all tumbling and cascading upon itself in a kind of shambolic construction which constantly threatens to fall down upon itself. But all the while, as he seemingly casually is creating these seeming arbitrary events and twists, Dick gives readers these incredible moments, these flashes of insight, which reveal he has been managing his story well all along, until we amble to an ending which feels tremendously satisfying.

Ubik has a lot to do with psychics and psychic warfare between corporations who all aim to dominate each other. An attentive reader of Dick is well aware of his passion for both psychics and bizarre faceless corporations, but in Ubik he has created an elaborate, complex idea structure around the psychics – there are scales of precogs, and people who can cancel out precogs, and the literal rewriting of reality based on the work of the precogs, and a constant sense that nothing, absolutely nothing we see, is real — at the same time all of it is real.

Again Mr. Dick’s writings always make me sound like a madman when I try to describe them. The reviewer’s dilemma!

But that’s the transcendent mindset the author puts you in with Ubik. He grounds readers in reality and then just as quickly yanks reality away from readers. One minute he’s depicting home appliances which demand dimes to open a fridge and 50 cents to use the bathroom faucet. The next he’s describing a prosaic journey to the moon, no big deal just a regular day at the office. The next minute we are following the results of a human-shaped bomb and tracking survival, and we suddenly start seeing entropy appearing everywhere, and the whole thing just moves at the speed of an SST, though perhaps the pilot of the plane is going from New York to London by way of Shanghai.

Is this review vague enough? I apologize, reader. As Vicki points out, I could be more specific, but seriously, if this sounds at all up your alley, Ubik will be a tremendously memorable read for you.

Which leaves the very tough question of a rating for this book. If Androids Dream is the absolute apex of science fiction (and I think it is), this book is one rung slightly below that level – if only because no character is quite as vivid as that book’s complicated and completely memorable Rick Deckard. That is a five star book, which means I give Ubik…

4½ stars

by Gideon Marcus

Brighter than a Million Suns

China's got the Bomb, but have no fears—they can't wipe us out for at least five years…

So sang satirist Tom Lehrer in 1965 for the television show That Was the Week that Was. Well, here we are, about five years later, and the Chinese have graduated to the big time. 18 months ago, they tested their first H-Bomb, the big firecracker that involves nuclear fusion rather than fission, with a damage yield equal to more than 100 times that of the Hiroshima A-Bomb. A try at #2 last year was a dud, but one detonated less than a fortnight ago went off just fine, creating a 3 megaton blast.

Radio Peking announced the blast on December 29th, but the Atomic Energy Commission had detected the blast the day before. It was apparently timed in celebration of Mao Tse Tung's 75th birthday. (In China, if you go carrying pictures of the Chairman, you will make it with someone…)

The bright…uh…positive side to this is that China's missiles, if there be any, are probably mostly pointed at the Soviet Union. Apparently, the Russians have beefed up their border divisions, and inter-Communist relations are sub-frosty.

So perhaps we have another five years…

Bigger than a half-dozen magazines

On the homefront, the latest issue of Galaxy, the magazine with half again as much content as all the others, offers some boffo entertainment as well as a few duds.

by John Pederson Jr.

To Jorslem, by Robert Silverberg

The ever-productive Silverbob offers up what may (but may not) be the final installment in his vivid Nightwings series. I'm sure we'll see a fix-up soon, a la To Open the Sky. According to Bob, this is his modus operandi—sell novellas to Galaxy editor Pohl, and then corral them into a novel.

by Jack Gaughan

Following directly on the heels of the last story, the invaders have fully Vichy-ized the Earth. Tomis, formerly a star-surveying Watcher, and then an historian of the caste Rememberers, is now a Pilgrim. Accompanied by the haughty Olmayne, cast out of the Rememberers for her slaying of her husband to be with the (now dead) former prince of Roum, the two make their way toward the holy city of Jorslem. Tomis is burdened not only with Olmayne's company but also the knowledge that he has sold out humanity, giving the invaders records of the Terran subjugation of the aliens' ancestors—thus justifying the invasion.

The story is something of a travelogue, something of a search for redemption, and it's written absolutely beautifully. It's not New Wave, exactly, but it's qualitatively different from what filled Galaxy last decade (or, indeed, what continues to fill Analog). Maybe Silverberg is leading a one-man revolution.

"Jorslem" does not quite achieve five stars, however. The plot is thin, even as (and perhaps especially as) a climax to the series. The happy endings come too suddenly and a bit implausibly. Female characters exist to be lovers or harpies.

Nevertheless, the world is so beautifully rendered, and the prose so masterfully done, that you'll enjoy the journey regardless.

Four stars.

Now Hear the Word of the Lord, by Algis Budrys

An alien race has controlled the world since 1958, secretly and tirelessly infiltrating every level of our society. One lone voice, a representative of the World Language League, finds a member of this cabal and threatens to kill him in order to learn the true extent of the invasion. The truth is shocking enough to blow your circuits.

A humdrum plot, but excellent, sensual telling. Four stars.

The War with the Fnools, by Philip K. Dick

by Bruce Eliot Jones

Another aliens-among-us story. This time, the baddies are the Fnools, who perfectly ape members of a given profession—realtors, minor cabinet officials, what have you. Only one thing gives them away: they are all only two feet tall.

But what if there was an easily accessible way for them to grow to human height? All hope would be lost!

This is a silly story, and most of the goodwill it earns is thrown away by the rather tasteless ending.

Two stars.

Golden Quicksand, by J. R. Klugh

by Jack Gaughan

The ferret ship H.L.S. Solsmyga is running for its life from two Grakevi raiders at thousands of times the speed of light. Its crew are protected from the tremendous accelerations involved only by the use of liquid-filled, individual pods, linked by the computerized Shipmind. If only the Solsmyga could use its superior maneuverability to ditch its pursuers; but in fact, Commander Yuri Hammlin's mission is to lead the raiders into a trap.

The running battle is competently presented, with lush, pseudotechnical detail, and Gaughan peppers the story with pretty, albeit superfluous, pictures. Ultimately, though, it's just a combat story. There is an attempted stingy tail, but it's more of an appendix.

Three stars.

Our Binary Brothers, by James Blish

by Brock

A driven man achieves everlasting success on Earth, but that's not enough. Repelled by humanity's technological quagmire, he longs for a simpler, cleaner world. And he finds one orbiting a hitherto undiscovered dwarf star just a fifth of a lightyear away. There, he sets himself up as a God and slowly leads the unwashed masses there toward a better civilization.

But planets comprise multiple populations, and not all are as backward as the hill people first encountered by the Terran…

A well-written but one-note vignette. Three stars.

For Your Information: The Island of Brazil, by Willy Ley

This is a fascinating piece on a variety of Atlantic land masses that never were. It's a nice complement to his piece on Atlantis.

Five stars.

Kendy's World, by Hayden Howard

by Reese

Kennedy Olson was born to high hopes just before the National Emergency turned the United States into an increasingly autocratic police state. After the death of his hippie, goodnik father, the boy coasted through life on his athletic skills and his winning smile. Come his junior year in high school, "Kendy" had more than a dozen scholarship offers, but the most persuasive came from the small California campus of National University. Seemingly too good to be true, the old-fashioned college offered a well-rounded education, sports opportunities, and a chance to make a difference.

Except that NU is really a training ground for spies, and the big bad isn't the Soviets, but the unspeakable, top secret horror they found when they tried to land on Phobos…

From the author that brought us The Eskimo Invasion, this story appears to be the setup for another serialized novel. The writing is strictly amateur, and there's not much story here—just a series of unpleasant events. I am curious about the alien menace, though, if it ever be developed.

Two stars.

Finish with a bust

As promised, there's lots of good stuff, and a fair bit of mediocrity in this first Galaxy of 1969. Ending with the weakest tale probably makes sense, but it does leave a bitter taste in the mouth. Nevertheless, the issue finishes on the positive side of the three-star divide, and that's a good enough New Year baby for me!

How about two of them, with Dick Martin from Laugh-In…

by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

Last month marked the 20th anniversary of the founding of the UK’s National Health Service. There are many issues with it, patients often wait for hours to see a GP, doctors trained by the service are regularly leaving for better paid work overseas, and many of the hospitals taken over from the private sector are in disrepair and not fit for the modern era.

Many of the major issues come down to spending choices. There are continually new innovations coming out that are expensive to use. For example, would it be better to spend the money on the new dialysis machines, rebuilding hospitals or reducing staff to patient ratios? All are important but they cannot all be achieved.

However, in spite of this, it has already become a beloved institution. There are few that want to go back to the system of voluntary hospitals and medical aid societies, and the principle of a health service free at the point of use is hugely popular.

Both of the publications I am reviewing this month are similar to the NHS in this manner. They may be relatively recent and not without their flaws but are still loved for what they do.

Orbit 3

Much like its British equivalent New Writings in S-F, Damon Knight seems to have a stable set of writers to draw from, with 4 of the 9 authors in this issue having appeared in a prior volume.

Mother To The World by Richard Wilson

Martin Rolfe and Cecelia “Siss” Beamer appear to be the last survivors of biological attack on the US by China. Whilst Siss is devoted to Rolfe, she also has an intellectual handicap, and he grows increasingly depressed about his situation.

Yes, this is yet another “Last Man” story, the twist being that the lead here is an unpleasant creep. Maybe others want to read about domestic abuse and incest. I do not. Add on to that statements about being surprised that a “backward country” like China could develop powerful weapons (the same country that built a hydrogen bomb last year) and I found myself annoyed at the entire thing.

One star

Bramble Bush by Richard McKenna

We are told that McKenna’s back catalogue has finally been exhausted so this is the last of him we will see in Orbit, and it is his most baffling tale.

In a future where man has explored much of the galaxy, a team is dispatched to Proteus. This planet, in Alpha Centauri, has never been landed on, as every prior mission has mysteriously had to abort before arriving. After making landfall they encounter what appear to be primitive humans who they are unable to communicate with. But after these Proteans perform a ceremony, the world gets a lot stranger for the crew.

We are told this story “…deals with one of the most perplexing questions in relativity…If all four spacetime dimensions are equivalent, how is it we perceive one so differently to the rest? [Mckenna gives a] solution which involved the anatomy of the nervous system, symbology, anthropology, the psychology of perception and magic."

It is possible that is what the story is about. I was honestly utterly confused throughout.

Two Stars, I guess?

The Barbarian by Joanna Russ

Continuing the adventures of Alyx in this fourth installment of her tales. She is now 35 and back in the ancient world (I presume after the novel Picnic on Paradise as there is a reference to her disappearance) when she is approached by a mysterious powerful figure who offers her anything she wants for just one deed. To kill a future dictator who is currently only six months old.

Russ continues to impress with these adventures, finding ways to expand the world and offer new situations for Alyx to grapple with. Here the tables are turned on her somewhat, as she is now dealing with someone more powerful who looks down on her. How she navigates the situation is fascinating and reveals much more about her. Whilst I wouldn’t rate this quite as highly as the prior installments, it is still very good.

Four Stars

The Changeling by Gene Wolfe

A Korean war veteran returns to his hometown in the US. Everything seems much the same except for young Peter Palmieri, who has not aged. What is more, no one else remembers Peter as being alive back then. Is our narrator suffering from Gross Stress Reaction? Or is something stranger going on?

I found this a well-told story but also fairly obvious and not doing anything I hadn’t seen before.

Three Stars

Why They Mobbed the White House by Doris Pitkin Buck

Hubert is a veteran who has become frustrated with the growing complexity of completing his tax return, so he leads a movement to have them done by supercomputers. But will the machines be any happier with this state of affairs?

As I come from outside the US, the complexity of filling out their tax returns is such a mystery to me. Not only could I not relate, I found this silly and dull.

A low two stars

The Planners by Kate Wilhelm

In a large research facility, monkeys are being given pills to test if it will increase their intelligence, along with the intellectually handicapped and prisoners. Do they have the right to do this? And is this all that is going on?

This is another of the kind of story popularized by Flowers For Algernon. It has some interesting touches, but I don’t think it rises significantly above the crowd.

Three Stars

Don't Wash the Carats by Philip Jose Farmer

In this experimental vignette, surgeons find a diamond inside a person.

A couple of years ago I considered Farmer to be one of the best people writing SF, but he has recently gone off the rails. This is described as “a ‘polytropic paramyth’ – a sort of literary Rorschach test”. Well what I see is pretentious nonsense.

One Star

Letter To A Young Poet by James Sallis

In this epistolary tale, Samthar Smith writes to another young poet back on Earth about his life and works.

This is a pleasant little piece where a writer looks back on his life and ponders about it. There is not a huge amount to say about it, but it is enjoyable.

Three Stars

Here Is Thy Sting by John Jakes

It all starts when Cassius Andrews, middling journalist, goes to pick up his brother’s corpse and finds it missing. This sends him on a surreal journey involving an old WBI agent, a superstar singer and a mad scientist.

I found it fitting that this is the longest piece in the anthology but has the shortest introduction. It rambles on for pages without much there and I found the conclusion to be rather odd. I don’t see that if we could remove the fear of the act of death (not the ceasing to be, but the momentary pain) everyone would become melancholy and cease to have a purpose. If anything would that not make people more willing to take bigger risks? The one thing I will say for it is Jakes is able to spin a yarn well enough to keep me reading to the end.

Two stars…just.

Famous Science Fiction #7

This quarter’s cover is a detail of the cover from August 1929’s Science Wonder Stories by Frank R. Paul.

I have to say I find this Famous version much less effective. In a short article on the subject, it states that it is the first time a space station was illustrated on a magazine cover but adds some criticism for it seeming old fashioned, due to the lack of technical articles available to work from in the period. Interesting enough for what it is.

Men of the Dark Comet by Festus Pragnell

This story and the next are from the summer issues of Science Wonder Stories in 1933.

In a far distant solar system, a planet’s natural satellite had been set loose in order to escape a disaster from their sun. This “Dark Comet”, as it becomes nicknamed because it absorbs all light, eventually enters Earth’s system.

Heathcoate, the commander of the spaceship Aristotle, is rendered unconscious by the application of the Martian drug Borga. He wakes up on an out of control ship, his cargo gone and the only person left on board being a prisoner, the drug addict Boddington. Boddington is able to deduce Martian pirates were behind this, working with the native authorities to secretly build up their own space fleet.

Crossing paths with the comet, they manage to effect a landing. Inside they find themselves among a species of alien “Plant-Men”, Boddington hopes to stay and learn more, Heathcote wants to return to Earth to warn of a potential Martian invasion.

Whilst I am not opposed to slow starts in fiction, this novella is glacial. So much irrelevant detail is included it is hard to get a grip on the central plot for some time. It includes some interesting elements, such as Martians having three sexes for reproduction and an interplanetary drug trade, but mostly it is irritating. At the same time, the Martian invasion plot feels cliched.

What is interesting enough to raise it up are the attempts to communicate with the plant creatures. Pragnell does a good job of making them seem truly alien, with contact taking place via the electro magnetic spectrum.

A very low three stars

The Elixir by Laurence Manning

We now come to the conclusion of the five part Man Who Awoke saga. To quickly recap for the unfamiliar, Norman Winters developed the means of putting himself to sleep for thousands of years and has been waking up further and further in Earth’s future. At the end of the last story we learnt that Winters has set his device to wake him up in the year 25,000, but that Bengue has also decided to duplicate his process and follow him.