by Gideon Marcus

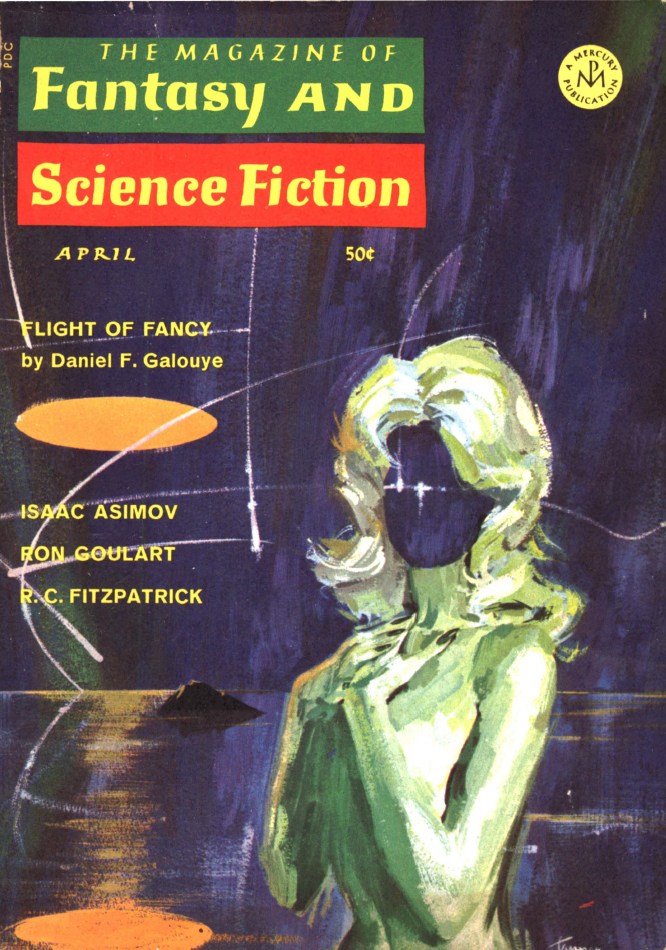

Pleasures of the Flesh

There are lots of different kinds of science fiction, from the nuts-and-bolts problem-solving variety one might call the Astounding style, to the literary style of the British New Wave, to the softly surreal speculation that often characterizes Galaxy. This month's issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction is one of the more sensual mags I've read in a long time, putting you, the reader, firmly into the viewpoint of its protagonists. From an SFnal perspective, the pickings are pretty slim, the speculations rather shallow. But from a visceral point of view, well, each story sends you pretty far out, making for a perfectly satisfactory experience whose highlights come, welcomely enough, at the beginning and the end.

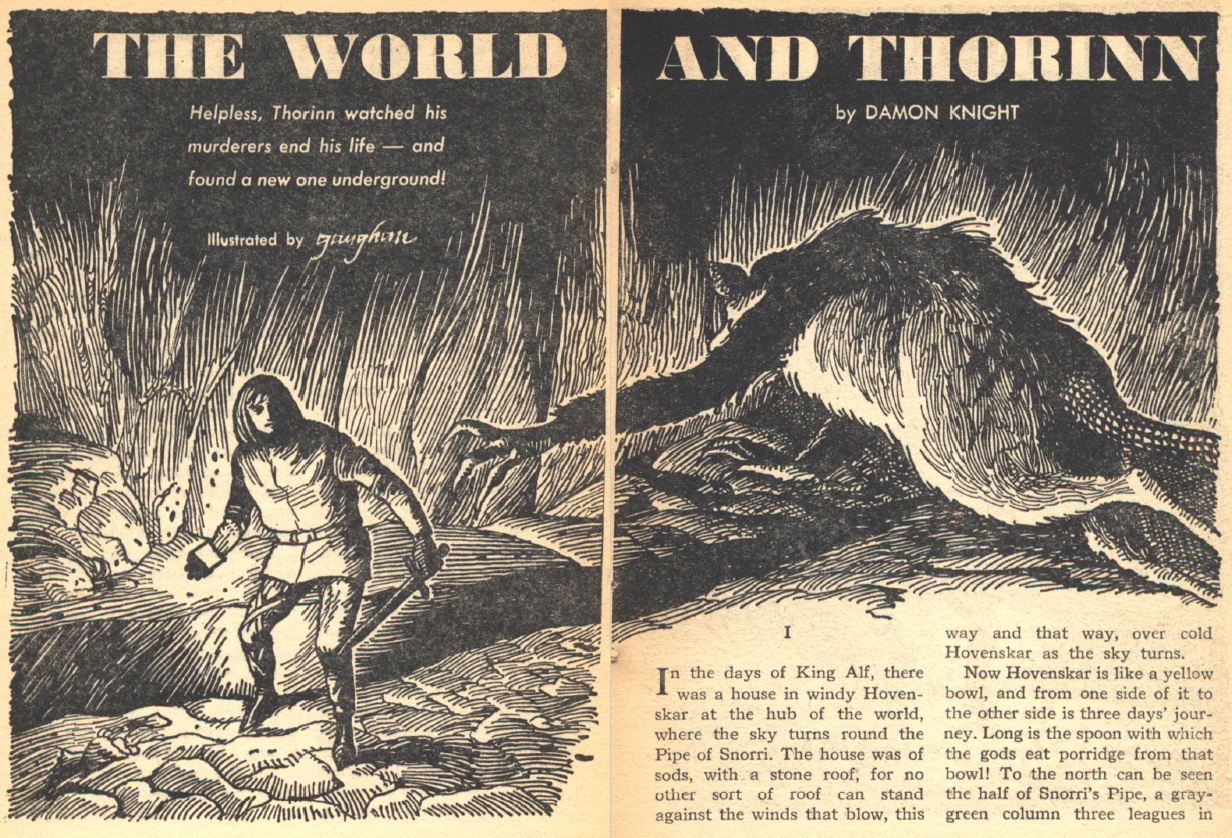

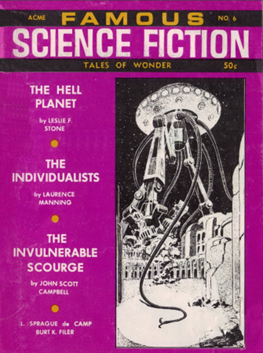

by Russell Fitzgerald (this suggestive cover is a little frustrating as it gives away the end of the story it illustrates…)

Strange New Worlds

Lines of Power, by Samuel R. Delany

First up, and rightfully so, is the latest novella by a man who has taken SF by storm. It is set in or around the year 2050, when the world has been knit by endless power cables, providing no limit of electricity and prosperity. The lines are laid out by self-contained crawler units (think the highway patrol motor homes from Rick Raphael's Code Three). By the middle of the 21st Century, all of the world, from Siberia to Antarctica has been knit with energy.

But there are occasional holdouts. One such Luddite concentration is in Canada, where a flight of future-day motorcyclists, soaring on winged choppers, have made their haven in the woods. These "angels" are violently opposed to the encroachment of the self-described "demons" and "devils" that comprise the Power Corps crew of the "Gila Monster".

It is progressive in the extreme, with women bosses and free love: interracial, intergenerational, and any-sexual. Modern-day (1968) hangups are completely discarded in a manner that Purdom pioneered and Delany has perfected. At the heart of the story is the moral question, one we've seen explored on Star Trek several times–is it right to give the fruit of knowledge to those who actively reject it?

Like all Delany stories, this is a highly sensory piece, although it also requires close reading, as Delany likes to be a bit sparse with his linking sentences. It's a simple story. You will find no revelations, and the characters are bit shallow. Chip (the name by which the author traditionally goes) has his kinks and tics, and they are all on display here, suggesting that this was a labor of love, but not necessarily too much effort.

Thus, a pleasant, but slightly hollow four stars. You could start a magazine with much worse!

by Gahan Wilson

The Wilis, by Baird Searles

This is a beautifully told spotlight on an opera company, from the pen of someone as experienced with the field as, say, Leiber is with the theater. Honestly, the supernatural components are almost superfluous, coming as they do at the end of the story, with little surprise and rather clunky integration. But without them, I suppose the piece would not have been published, at least in this magazine.

Three stars, as well as the prediction that we won't ever see anything by Mr. Searles again–this was obviously a very personal piece, and I would be surprised if he has more ideas in him. But you never know!

Gifts from the Universe, by Leonard Tushnet

Another fellow who writes what he knows is Leonard Tushnet, whose pieces have a delightful yiddish tinge to them. Here, a retailer of gifts happens upon a wholesaler in ceramics whose stock is beautiful beyond compare–and at such a deal as to prices! But the rather unusual wholesaler only accepts silver as currency, and his tenure and his wares have a definite expiration date…

You'll enjoy it; you'll even remember it. A pleasant three stars.

Beyond the Game, by Vance Aandahl

The second-darkest piece of the issue comes from a young man who filled the pages of F&SF in the early '60s but then disappeared in 1964. He returns with the tale of Ernest, a boy trapped in a sadistic game of dodge ball, huddled for safety behind the broad backsides of two of his teammates. When the sadistic Miss Argentine (who may be a robot) notices the cowering tyke, she commands all of the kids to teach him a lesson. In doing so, she unlocks the child's unearthly powers, which facilitate his escape.

Nicely told, this feels like it was conceived by Aandahl when he was quite young, and he waited until he was deft enough with writing that he could effectively put it to paper. It's fine for what it is, which isn't all that much. Three stars.

Dry Run, by Larry Niven

Now for the darkest piece, a fantasy from a fellow I normally associate with straight-forward "hard" SF (though I suppose The Long Night, which also appeared in F&SF, was also an exception).

Murray Simpson grips the wheel of his Buick, cigarette smoldering between his white knuckles, the stiffening body of his Great Dane in the trunk. The dead dog is Simpson's doing, a dry run for the murder of his wife.

An accident forestalls the culmination of Simpson's plan. Those who judge in life-after-death decide to find out how things might have otherwise played out.

Upon first reading this decidedly unpleasant tale (not just the subject matter; the depiction of a San Diego freeway traffic jam is too spot on for any local's comfort!) I was inclined to give it three stars. After reading it aloud to my family as their bedtime story, the piece came to life for me.

Thus, four stars.

Backward, Turn Backward, by Isaac Asimov

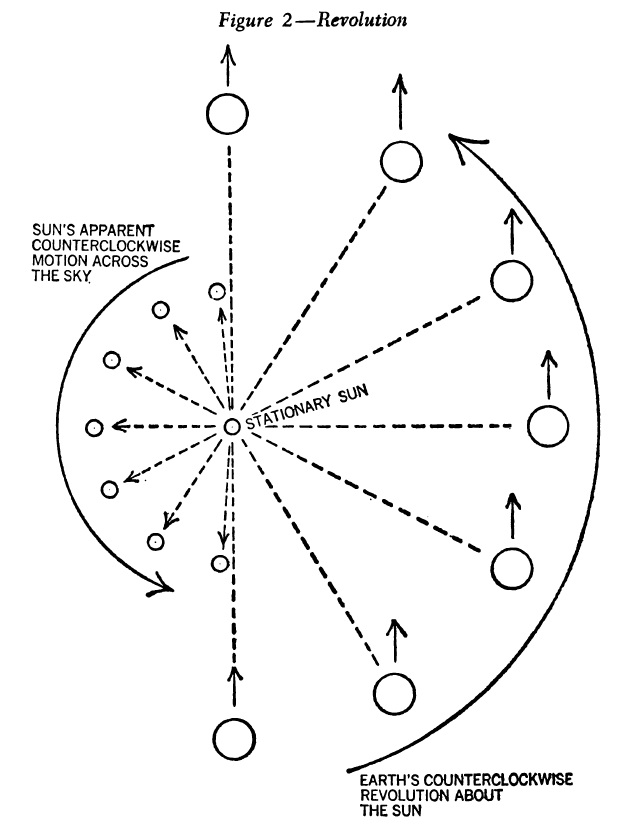

The Good Doctor takes a stab and planetary rotations and axial tilts in this month's science fact article. I do appreciate that he advances his own theories as to what caused both the "direct" (counter-clockwise) rotations of most of the planets (the natural spiraling in of the bodies as they coalesced) as well as what caused Uranus to spin on its side and Venus to spin retrograde (perhaps collisions early in formation).

It's still a somehow dry and shallow piece. I'm not quite sure what I want from Isaac, but he's not quite doing it for me these days.

Three stars.

A Quiet Kind of Madness, by David Redd

In the snowy winter wastes of Finland, lone huntress Maija comes across a strange creature, shivering and near death. He looks something like a polar bear, but not quite. As she nurses him back to health, she discovers he is intelligent, telempathic, and from an entirely different world. When they sleep, her new Snow Friend takes her to his place-without-men, a warm place of perpetual sunshine. It is a paradise to Maija, who would just as soon leave our world behind.

For a man pursues her, the relentless Igor, who six months tried to have his way with her, and is now back to claim her again. But it is not just fear of Igor that spurs her on, rifle in hand, to fend off the man, but fear for Snow Friend, who will be just a pretty pelt to Igor.

As with Redd's previous story, Sundown (which also features a snowy landscape–Redd must have a deep familiarity with icy terrain), Madness is vivid and compelling, and more artfully told than Sundown. It's almost a contemporary Oz story, with Snow Friend a refugee from a magical land. It's also a beautiful character study, of the bitter and solitary Maija, of the not-entirely-bad Igor, of the well-meaning but still male Timo, and of the sweet, alien Snow Friend.

This time, it is not for lack of deftness that this piece falls just short of five stars, nor for its almost incidental fantastic qualities, but simply because the end is not quite satisfying–almost as if Redd, himself, was unsure how to conclude the piece.

Still, it kept me hooked. A high four stars, and my favorite piece of the magazine.

Back to reality

As my colleague Kris puts it (and Kris insists it originated with me), Fantasy and Science Fiction's experiment at being a monthly version of Dangerous Visions appears to be paying off. The May 1968 issue scores a solid 3.5 stars with no clunkers in the mix. If none of the stories quite achieves classic status, well, maybe next month.

I only wonder where all the women went, given that the pages of F&SF were once the bastion of SFnal femininity. Maybe they're all writing Star Trek scripts.

In any wise, pick up this issue and enjoy. In this tumultuous day and age, it's nice to breathe the rich air of other worlds for a while.

Speaking of other worlds, come join us tonight at 8pm (Eastern and/or Pacific) for the rerun of "The Doomsday Machine", one of Star Trek's best episodes!

Here's the invitation!

![[April 20, 1968] A treat for the senses (May 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/680420cover-672x372.jpg)

![[April 12, 1968] Darkness (May 1968 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/SMALLCOVER-672x372.jpg)

This tale appeared in the December 1956 issue of the girlie magazine Caper, attributed to Spencer Strong (Ackerman again) and Morgan Ives (Marion Zimmer Bradley.)

This tale appeared in the December 1956 issue of the girlie magazine Caper, attributed to Spencer Strong (Ackerman again) and Morgan Ives (Marion Zimmer Bradley.)

![[April 10, 1968] Things Fall Apart (April 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/amz-0468-cover-447x372.png)

![[April 2, 1968] Asking the big questions (May 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/IF-1968-05-Cover-569x372.jpg)

Alexander Dubček addresses the nation after taking office.

Alexander Dubček addresses the nation after taking office. Supposedly for Dismal Light, which doesn’t even have two male characters. Generic art by Pederson

Supposedly for Dismal Light, which doesn’t even have two male characters. Generic art by Pederson![[March 28, 1968] Design for effect (April 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680328cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 26, 1968] Scandal! <i>New Worlds</i>, April 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/New-Worlds-April-1968-672x372.jpg)

Cover by Stephen Dwoskin

Cover by Stephen Dwoskin

![[March 20, 1968] Missed opportunities (April 1968 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680320cover-666x372.jpg)

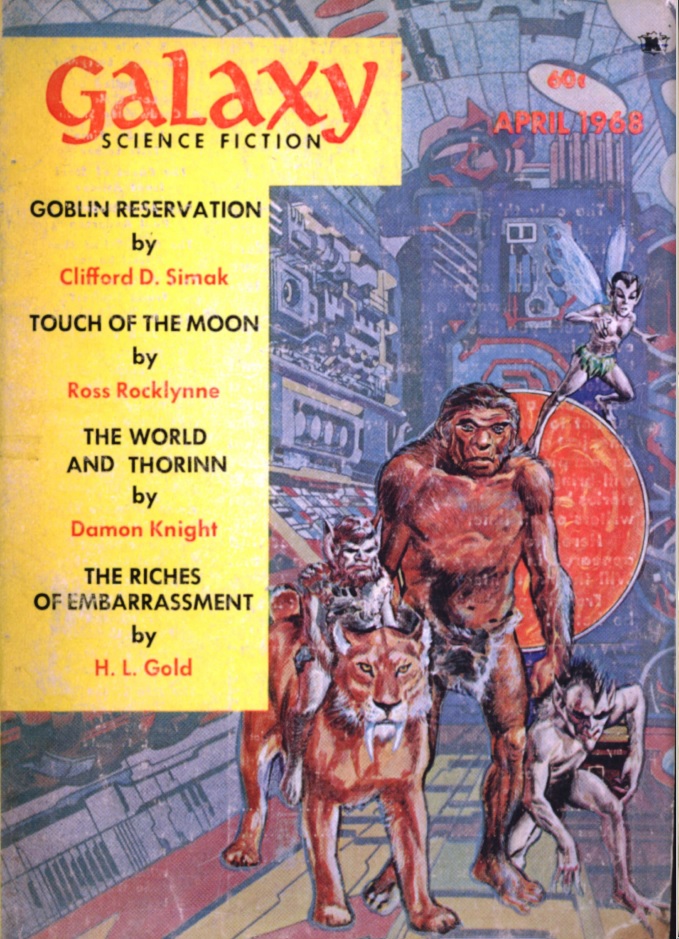

![[March 6, 1968] Trend-setter (April 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680306cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 4, 1968] Everything Old is New Again (<i>New Writings in SF-12</i> & <i>Famous Science Fiction</i> Issues #4-6)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Cover-396x372.png)

![[March 2, 1968] Rules and Regulations (April 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/IF-1968-04-Cover-639x372.jpg)

The stars of the show. (l.) Jean-Claude Killy sporting his medals. (r.) Peggy Fleming in her spectacular performance.

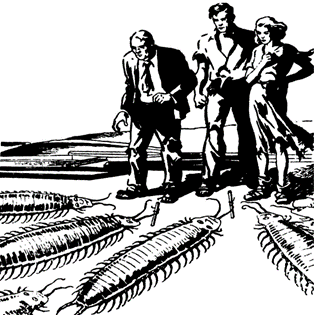

The stars of the show. (l.) Jean-Claude Killy sporting his medals. (r.) Peggy Fleming in her spectacular performance. The Advanced Guard prepare to study the fauna of Chryseis. Art by Vaughn Bodé

The Advanced Guard prepare to study the fauna of Chryseis. Art by Vaughn Bodé