by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

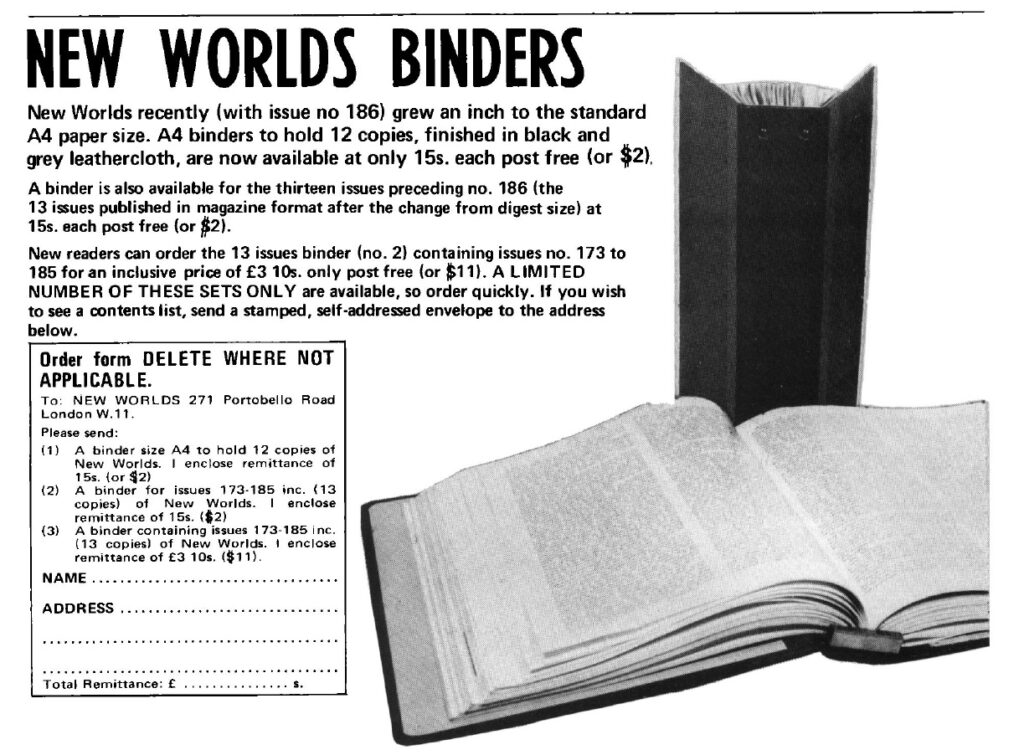

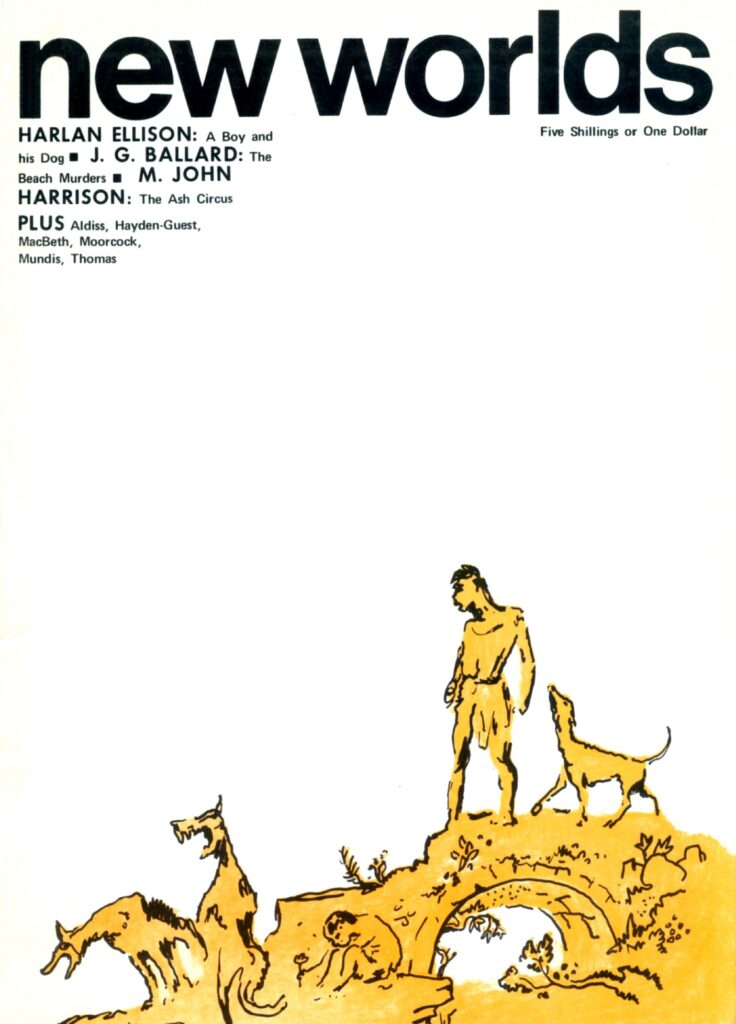

With this issue of New Worlds, number 190, we now seem to be getting back to a regular monthly schedule and the new style seems to be bedding itself down into a regular format – although this being New Worlds I suspect that they would hate any hint of things becoming routine.

Quick recap, then. Recently Charles Platt and Michael Moorcock stepped away from full-time editorial duties, leaving the magazine in the capable hands of Langdon-Jones. His first issue last month was a corker, with the first publication of a Harlan Ellison story in Britain (although to be fair I had read some of his other work published in the American magazines beforehand.) As a result, the new mantra seems to be that New Worlds even though under new management will continue to publish cutting edge, controversial material that defies borders and descriptions.

Each issue seems to continue a confounding mixture of good, bad and weird prose, not to mention poetry. Its appeal to me seems to be that I never quite know what I’m going to get next, although with the poetry I have a fairly good (or is that bad?) idea.

Anyway, on to this month’s issue.

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

We’re back to the odd pictures of people’s faces on the cover this month.

Lead-In by The Publishers

As is usual, information is given on the contributors. This month, Harvey Jacobs, Brian Aldiss, poet Libby Houston, science editor Dr. Christopher Evans, his secretary Jackie Wilson and a photo of author Marek Obtuowicz without any further detail.

The Moment of Eclipse by Brian W Aldiss

Photo by Gabi Nasemann

Photo by Gabi Nasemann

The Lead In tells us that Brian’s latest offering was inspired by Thomas Hardy’s Poem Inspired by a Lunar Eclipse written in 1902.

This however is a more contemporary work, about a modern film maker and his pursuit of Christiania, a woman he has met, despite the fact that she is married and with a son. So, a story of lust, combined with Aldiss’s quirky humour and his love of global places that we have read before – not to mention a parasitical worm that will frighten any devotees of Frank Herbert’s Dune!

I liked this generally – mainly because it shows Aldiss’s precise and illustrative prose without so much of the oddness exhibited in his recent Charteris stories. 3 out of 5.

The Negotiators by Harvey Jacobs

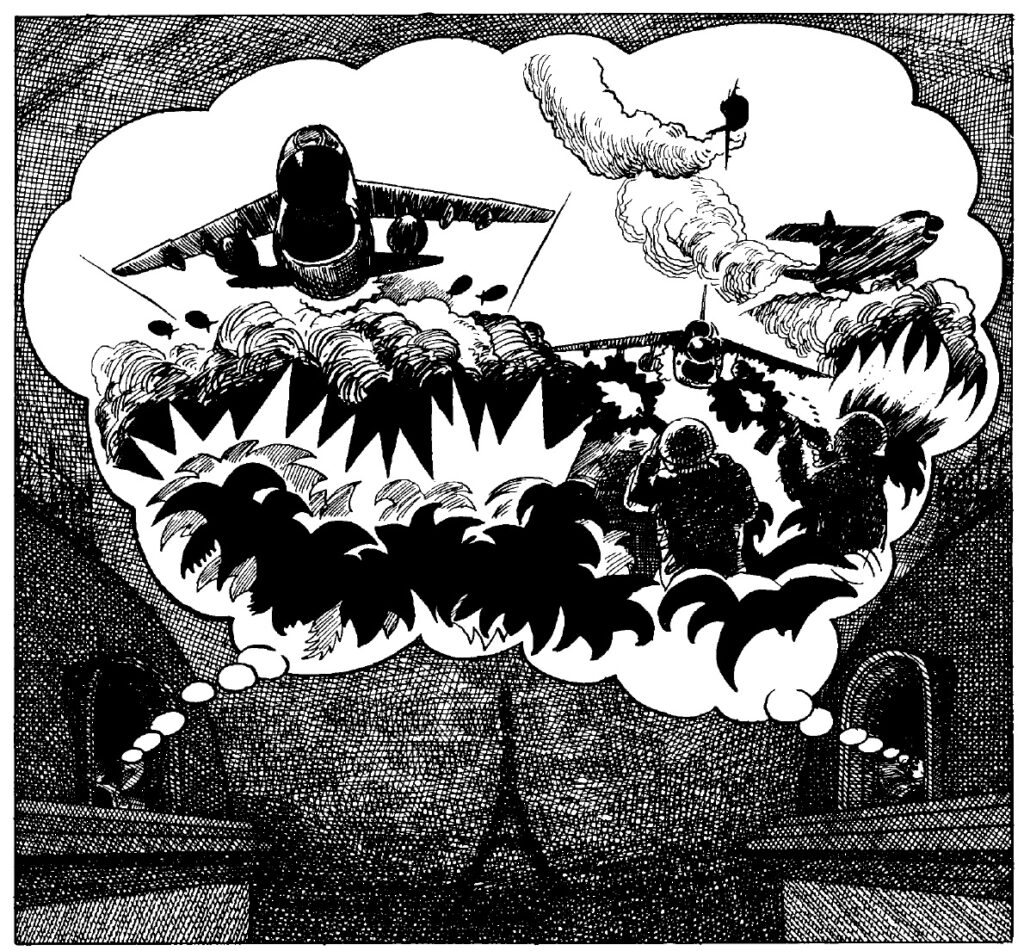

Image by Mal Dean

Image by Mal Dean

This story is set in Vietnam as a dialogue between two negotiators hoping to cease the conflict there. Whilst the two characters grow closer, the war continues. A story that through vivid imagery and prose, at times sexual, basically suggests that war is bad, but that love may bring peace, or at least agreement. 4 out of 5.

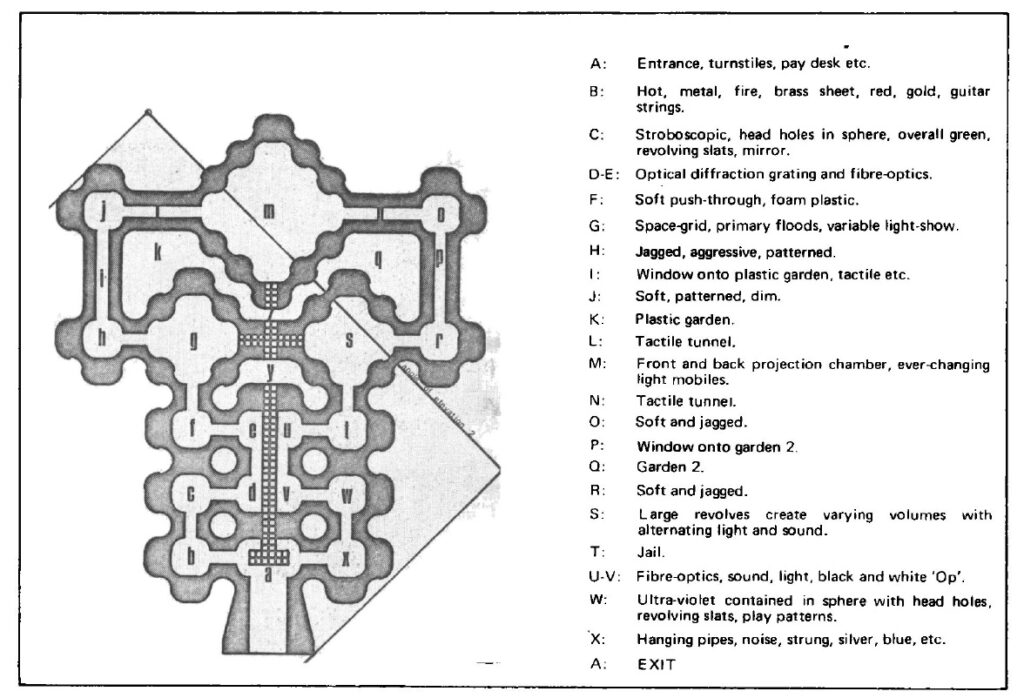

Article: The Responsive Environment by Charles Platt

Platt interviews Keith Albarn, an architectural artist who makes furniture and buildings that adapt and can be rebuilt to individual needs. These range from a funfair in Margate to theatre design, educational toys, and a fun palace in Girvan, Scotland.

A map of the Girvan Fun Palace, Image by Unknown

A map of the Girvan Fun Palace, Image by Unknown

3 out of 5.

A Cure for Cancer (Part 3 of 4) by Michael Moorcock

Image by Mal Dean

More fractured escapades with Jerry Cornelius. Much of this part has Jerry travelling the world in search of the missing techno-wotsit. Really though this gives Moorcock a chance to show us the world, from his own street of Ladbroke Grove, London, to trendy Soho and the King’s Road, Chelsea before going on to other places such as Las Vegas and Sumatra.

Cornelius meets his brother Frank again (last seen in the March 1966 issue of New Worlds as part of The Final Programme novel) and sister Catherine, in suspended animation, but really the story appears to mainly be a minor point whilst we examine the setting of a free world in decline. Most of these places have been bombed, London has an air-strike whilst Jerry is in it, Americans are filling the world with ‘advisors’ whilst dealing with civil riots of its own on home territory.

Things begin to make more sense and there’s a feeling that we might be drawing things to a close, as Jerry and the missing machine that he is in search of may be either the cause of the world chaos or the person most effective in having to deal with it. 4 out of 5.

Poems by Libby Houston

Image by Mal Dean

Image by Mal Dean

First thought: What must a young woman do to get published in New Worlds magazine? Write poetry, it seems, or be married to the magazine illustrator. (That is unfair, I know. New Worlds has championed women’s writing for years now, when they can get it.)

Six short poems here, and as such – they fill up space unremarkably. (Do bear in mind that I still find most poetry uninteresting, though.) At least they’re not written by the seemingly ubiquitous D. M. Thomas this month. 2 out of 5.

the hurt by Marek Obtuowicz

Photo by Gabi Nasemann

Photo by Gabi Nasemann

A new author. Sadly, this is one of those stories designed to try and shock without any real involvement on the part of the reader and filled with symbolism that seems meaningless.

Mostly dialogue based, it is a number of conversations between Peter and his sister, Pauline. Unsurprisingly, they discuss their lives in a depressingly bleak future, a world where sex seems meaningless and crying is forbidden. Perhaps even more unsurprisingly, Pauline is a brothel-owner and Peter and Pauline have an incestuous sexual relationship.

There’s something in there about emotional hurt being caused by events in the past, but I was too bored to look at it in detail. 2 out of 5.

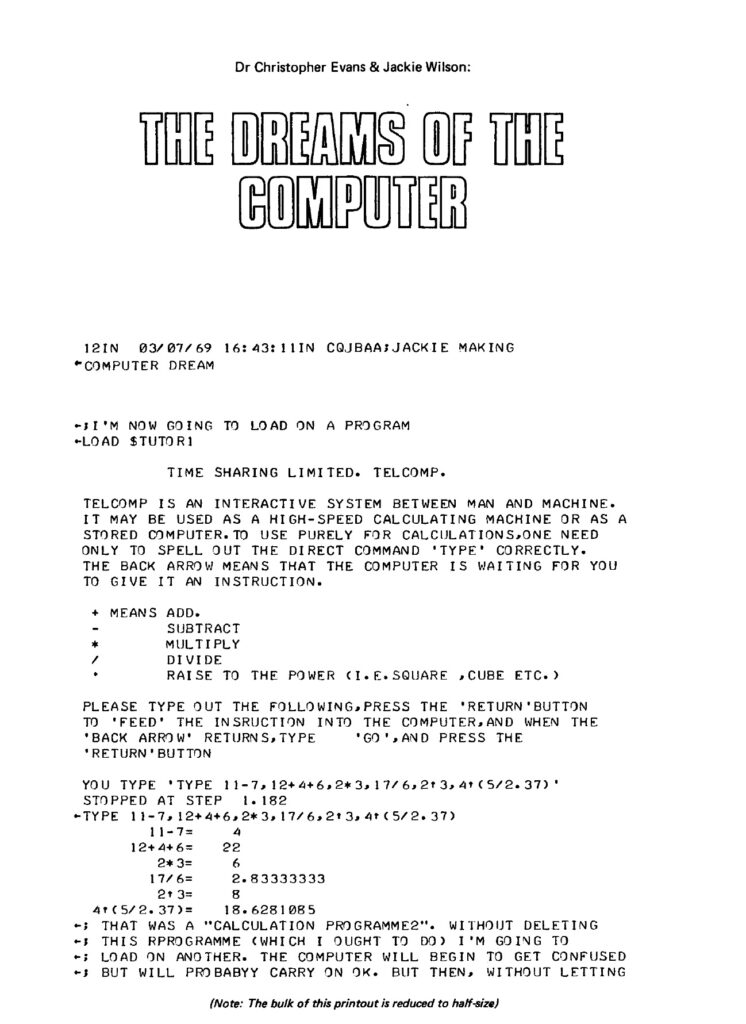

The Dreams of the Computer by Dr. Christopher Evans and Jackie Wilson

Written as if a computer programme, filled with lots of “Answer Yes or No” and “Go to” statements, Dr. Evans, with the help of his secretary, responds in kind to J. G. Ballard’s prose story, How Dr. Christopher Evans Landed on the Moon in issue 187 (February 1969) of New Worlds. I liked it. There’s a nice sense of absurd humour in it, but it loses some of its impact by being not as original as the Ballard version. I am also not sure it makes sense if you’ve not seen Ballard’s original piece. 3 out of 5.

A bumper crop of reviews this month, though most are not science fiction-related.

Book Reviews: Back in the U.S.S.R. by R. Glynn Jones

R. Glynn Jones reviews Art and Revolution, a book about the work of Russian sculptor Neivestny, whose opposition to Kruschev has made him a heroic and revolutionary symbol.

Book Reviews: Twilight Crucifixion of the Beastly Black Sheep by M. John Harrison

Harrison reviews The Spook Who Sat by the Door, a polemic book about a Black CIA officer which is “an incitement to riot”, Behold the Man by Michal Moorcock (which we reviewed here when it was a serial story), The Twilight of the Vilp by Paul Ableman, which is “weary, contrived and too long”, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep by Philip K Dick, a novel which is “beautifully constructed yet disappointing”, and the wonderfully titled The Beastly Beatitudes of Balthazar B, which is “moderately enjoyable”.

Book Reviews: Notes on the Management of a Spoiled Identity by Bob Marsden

Marsden reviews a book on the theory of game-play, a book on psychological theories and stratagems and a book on the discrepancy between what people think a person should be and what they really are. Nothing really of interest to me there. Moving on…

Book Reviews: From Alice with Malice by James Cawthorn

At last: Cawthorn reviews what we would broadly describe as fantasy and science fiction! Black Alice will be of interest here as it is written by two New Worlds regulars, Thomas M. Disch and John T. Sladek. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is well-received. So too a number of books by Michael Moorcock, including The Jewel in the Skull, The Ice Schooner and The Mad God’s Amulet. He then reviews a “disappointing” SF novel for younger readers, Undersea City by Frederik Pohl and Jack Williamson, and the “fairly entertaining” Twin Planets by Philip E. High. Lastly, and then rather oddly, Cawthorn reviews a book on rural uprisings in pre-Victorian England – who says New Worlds lacks diversity?

Book Reviews: Against the Juggernaut by John Clute

John Clute is a new reviewer here, although he has had fiction published in New Worlds before (A Man Must Die, November 1966.) Here he reviews a “simply godawful” book of poetry, Juggernaut by Barry McSweeney, a book by a new African writer who Clute describes as “an intelligent and urbane civil servant and diplomat, but a lame writer”, a novel about a group of Americans who translate the Oberammergau Passion Play into English and put it on in Texas as making the reviewer feel as if they had “just been forced to eat yesterday’s newspaper” and a detailed review on a book about the philosophy of Jean Paul Satre. They may not be books I would ever want to read myself, but at least the reviewer is entertaining.

Book Reviews: The Nondescript Heroes by Charles Platt

Platt reviews the autobiographical Gemini! by the recently-departed Apollo astronaut Virgil Grissom. He is disappointed by the book’s blandness and superficiality, eventually concluding that such an exciting and technological advancement is not served well by such pilots of limited expression.

Summing up New Worlds

Well, if New Worlds is all about ‘cutting edge, controversial material that defies borders and descriptions’, then this issue isn’t it. In fact, it is a solid yet rather conventional issue – admittedly conventional for New Worlds. There’s no photos of naked ladies, relatively little sex (although there is some – this is New Worlds, after all!) and stories that now seem rather typical of the new style of New Worlds.

In short, it is pretty much what to expect from the magazine, which is not a bad thing, but rather unmemorable, as it is not as determined to startle as some previous editions have been.

The most memorable thing about the issue is the new reviewer John Clute, who seems to be here to stir things up a little, although I do find it amusing to see both recently-retired editors Platt and Moorcock appearing in issues writing fiction and articles. Still around and not forgotten.

Anyway, that’s it, until next time.

![[April 24, 1969] The Strange New Normal <i>New Worlds</i>, May 1969](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/New-Worlds-May-1969-672x372.jpg)

![[April 12, 1969] A New Venture (May 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Venture-1969-05-Cover-494x372.jpg)

The first and last covers for the first run of Venture. Art in both by Ed Emshwiller

The first and last covers for the first run of Venture. Art in both by Ed Emshwiller This singularly unattractive cover is by Bert Tanner.

This singularly unattractive cover is by Bert Tanner.![[April 10, 1969] Low (May 1969 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/amz-0569-cover-490x372.png)

![[April 8, 1969] Distractions (May 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690408cover-428x372.jpg)

![[April 6, 1969] The Weight of History (May 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/IF-1969-04-Cover-500x372.jpg)

A map showing the location of Chenpao/Damansky Island

A map showing the location of Chenpao/Damansky Island Chinese soldiers pose with their captured Russian tank

Chinese soldiers pose with their captured Russian tank The cover illustrates Groovyland and is credited as courtesy of Three Lions, Inc., but see below

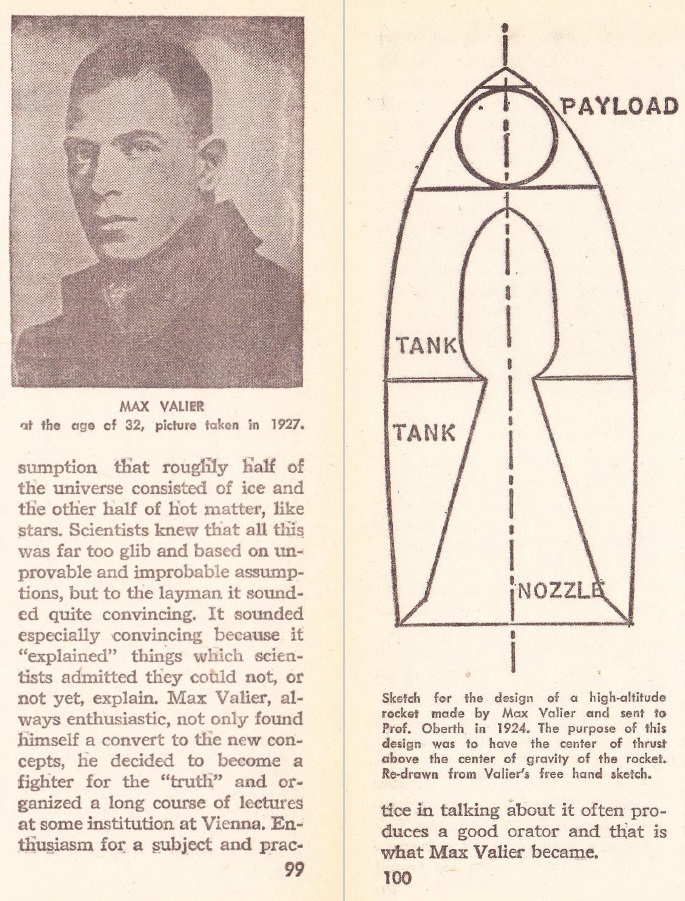

The cover illustrates Groovyland and is credited as courtesy of Three Lions, Inc., but see below![[April 4, 1969] Hey, Mack! (April 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690331cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 24, 1969] Apocalypse Impending? <i>New Worlds</i>, April 1969](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/New-Worlds-April-1969-672x372.jpg)

The named list from last month.

The named list from last month. Cover by Mervyn Peake.

Cover by Mervyn Peake. In a post-apocalyptic US we are told of teenager Vic and his telepathic dog, Blood. Vic is a teenage boy who spends his time scavenging the world for basic needs—food, companionship, and sex—as well as generally avoiding other groups, known as roverpaks, doing the same thing. They meet Quilla June – unusual because most women live where it is safer, underground. Vic rapes Quilla June before they are attacked by another roverpak. Blood is hurt in the scuffle. Quilla June escapes and returns to her underground home of Topeka.

In a post-apocalyptic US we are told of teenager Vic and his telepathic dog, Blood. Vic is a teenage boy who spends his time scavenging the world for basic needs—food, companionship, and sex—as well as generally avoiding other groups, known as roverpaks, doing the same thing. They meet Quilla June – unusual because most women live where it is safer, underground. Vic rapes Quilla June before they are attacked by another roverpak. Blood is hurt in the scuffle. Quilla June escapes and returns to her underground home of Topeka.

More poetry. Described as ‘a poem for light and movement’, Thomas manages to produce strange typewritten boxes that are at times undecipherable. A typical ‘form over content’ type piece. 2 out of 5.

More poetry. Described as ‘a poem for light and movement’, Thomas manages to produce strange typewritten boxes that are at times undecipherable. A typical ‘form over content’ type piece. 2 out of 5. The inevitable 'naked lady of the month' picture.

The inevitable 'naked lady of the month' picture. Artwork by Mal Dean.

Artwork by Mal Dean. More artwork by Mal Dean.

More artwork by Mal Dean.

![[March 20, 1969] Going through the motions… (April 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/690320cover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 10, 1969] Speed (April 1969 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/COVERHALF-672x372.jpg)

![[March 2, 1969] Dreams and reality (April 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/IF-1969-04-Cover-491x372.jpg)

Ayub Khan greets LBJ in Karachi in 1967.

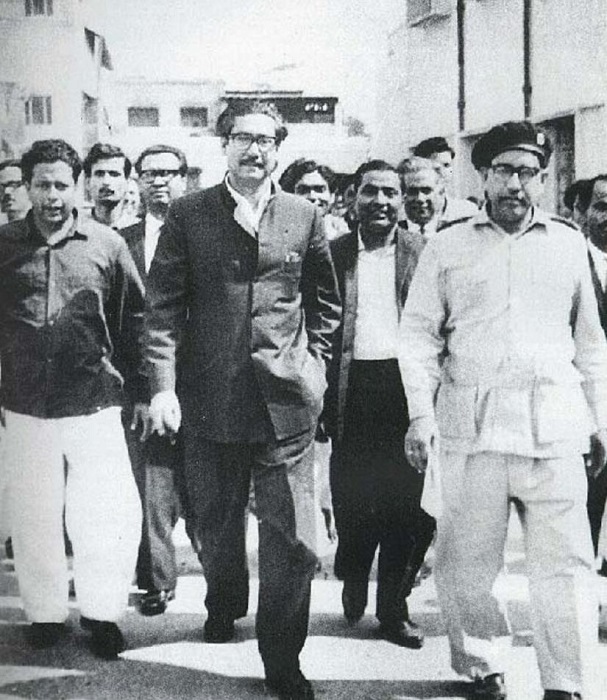

Ayub Khan greets LBJ in Karachi in 1967. Sheikh Mujib (center) emerges from prison.

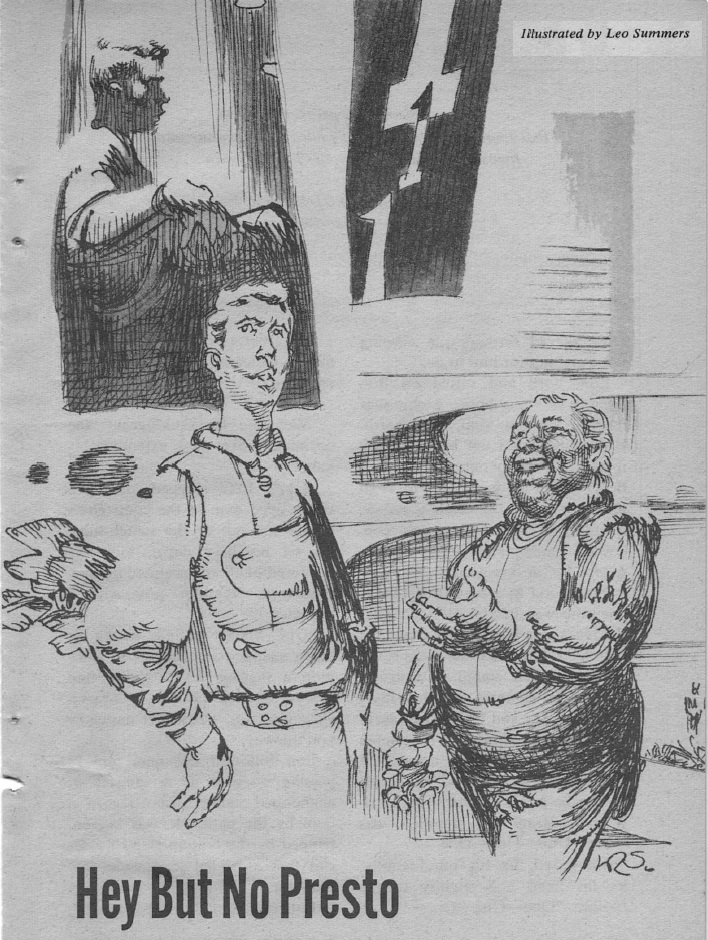

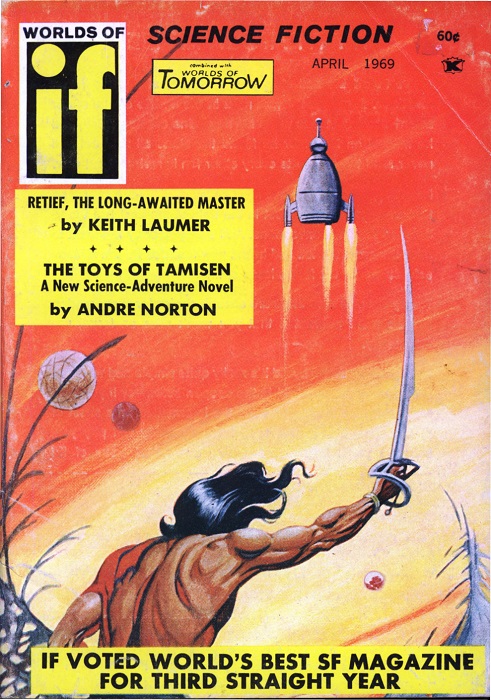

Sheikh Mujib (center) emerges from prison. Like I said, swords and spaceships. Art by Adkins

Like I said, swords and spaceships. Art by Adkins